-

A Brutalist Love Story

Boston City Hall

Text by Jessica Bridger

-

A proud Bostonian walks the freezing, icy grey streets with Northern reserve: impassive, quietly powerful and with a forbidding air. Boston City Hall stands stationary at the heart of the city with the same sort of harsh character. In Boston, we love with an austerity that belies an inner passion, and some of our best modernist buildings are expressive of this cultural commonality.

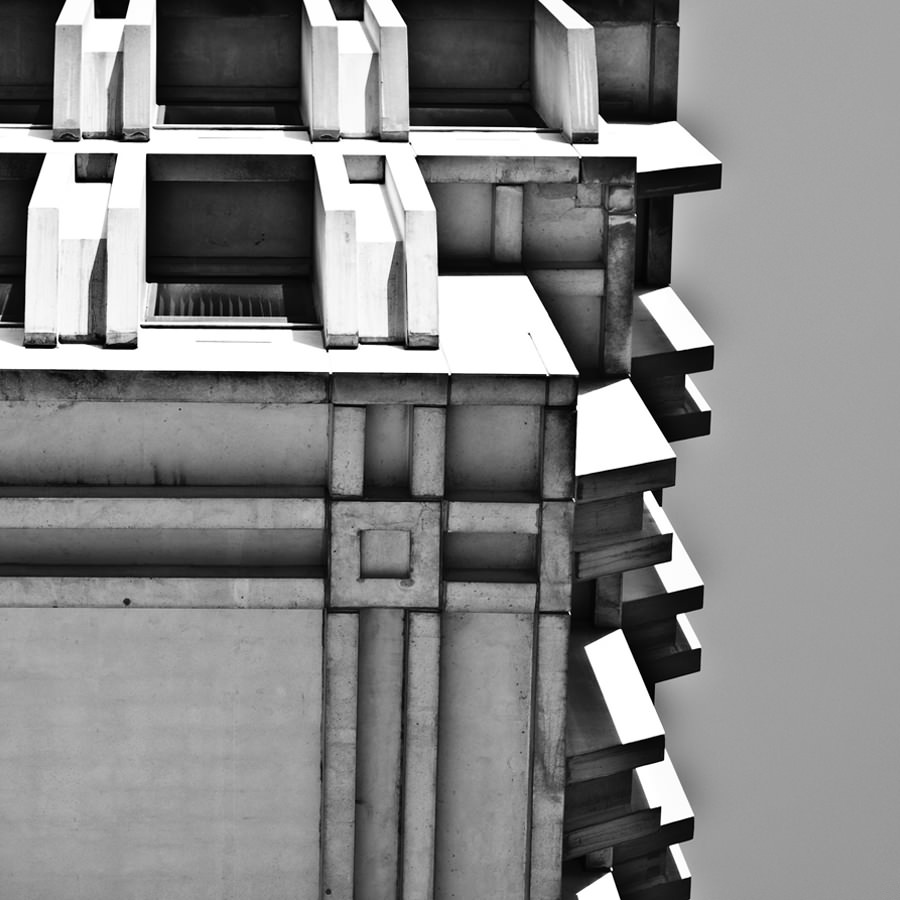

There is perhaps no brutalist masterpiece that is by turns more reviled and loved than Boston City Hall. The building was built as the result of a competition won by the architects Gerhard Kallmann and Michael McKinnell in 1962, and the public’s judgment of the building has oscillated between enthusiastic admiration and absolute hatred in the intervening decades. The hulking concrete volume of the building sits on a plaza like a giant red-brick fantasy roller-rink in the middle of Boston’s urban core. The failure of this public plaza is undeniable: the treeless brick expanse is boiling hot in summer and dangerously slick in Boston’s harsh winters. All photos: Mark McLean, 2012

All photos: Mark McLean, 2012 -

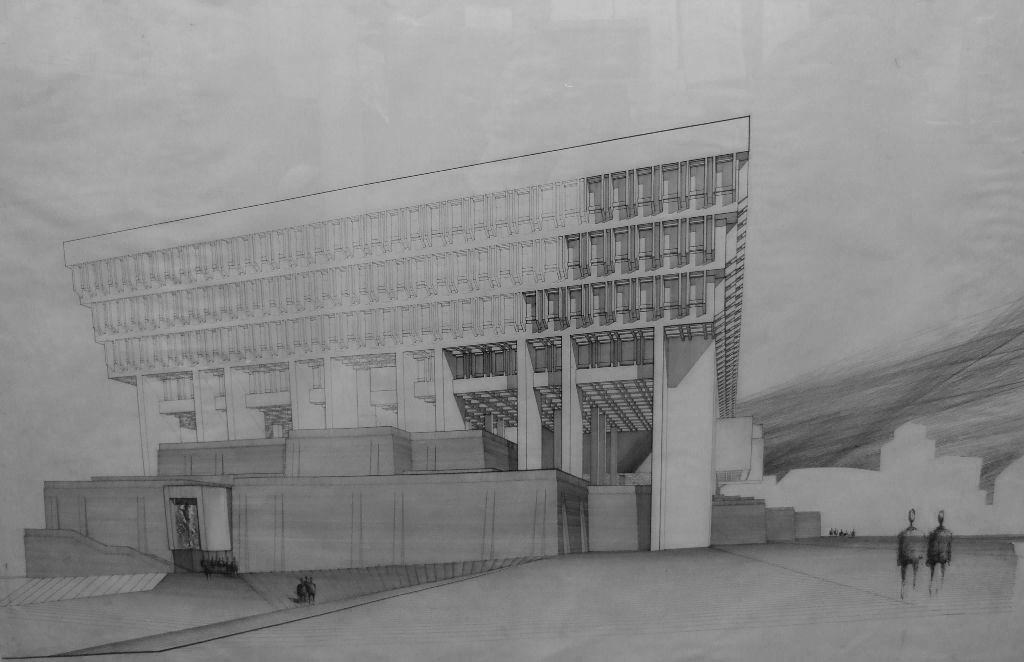

Drawings: Courtesy of Friends of Boston City Hall»The public’s judgment of the building has oscillated between enthusiastic admiration and absolute hatred.«

-

The showpiece of the building — and the section of the three-part concrete and brick building that most people identify as Boston City Hall — is its concrete mass, rising triumphantly out of the sea of brick. These parts of Boston City Hall were designed to demonstrate the importance of public political processes and politicians in Boston. The interior of this space has a central atrium, which, prior to 2001’s security alterations was fully open to the public, who could gaze upon their elected officials (on their way to pay parking tickets on one of the floors below).

The “success” of this building is a complicated issue. The exterior is striking; the interior, though rounds of renovations which have made a warren of walls, is stifling. Though brutalist architecture was somewhat popular during the 1950s and 1960s on the Eastern Seaboard, it was never embraced by an adoring public. The style is tied to early modernist construction practices where in-situ concrete — poured onsite, commonly into wooden formwork — was in Brutalist architecture left in a largely unfinished state, unthinkable before. Naked concrete: how outré! About half of Boston City Hall was constructed in-situ and half from pre-cast

»Form, in this case, seems to endure more sustainably than function.«

-

components. The grain of the casting form is visible in many cases, almost like a patina of the organic over an undeniably constructed mass.

Over the years, the organization Friends of Boston City Hall has championed the building against critics and supported calls to refurbish and substantially remodel. Calls to tear the building down or move its functions elsewhere have been voiced repeatedly and with some stridency over the years, and a plan to retain the structure but move city hall was halted due to the recession. For now and the foreseeable future it is civic business-as-usual in Boston. Boston newspapers still vacillate between reporting on the dismal interior conditions of the building and reporting on residents’ love of the structure. Regardless of its pragmatic function, the building has an iconic presence in the centre of the city. Form, in this case, seems to endure more sustainably than function. Hard-edged Bostonians, loving to hate what’s theirs, have adopted what many see as an ugly stepchild with a grudging pride, and in the end, even a bit of love.

»There is perhaps no brutalist masterpiece that is by turns more reviled and loved than Boston City Hall.«

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Architecture starts when you carefully put two bricks together. There it begins.«

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents