-

Fighting Nature

Creating resilient urban

environments against natural

catastrophesText: Susannah Drake

With Nature

Damage caused by a fire at Breezy Point in Queens, New York City after Hurricane Sandy. (Photo: Fox News)

-

In the wake of the deaths and terrible devastation to private property and public infrastructure from Hurricane Sandy, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo announced recently that he would seek 43 billion dollars in federal relief funds to help the New York metropolitan region rebuild in the hurricane’s wake. In the weeks following the storm, many ideas and options have been raised about what to do now, and in the future, to help those in need. It is time for a radical rethinking of urban life to address the realities of climate change on coastal cities.

In the aftermath of the Hurricane Sandy there has been a great deal of speculation about the use of flood gates. Designers and public officials often look to the Dutch for examples of water management technology. This seems sensible given that the Netherlands, a country with around 25 percent of its land area below sea level, employs many innovative strategies such as dykes, dams, and polders to manage seawater intrusion.

Cars are partially submerged in water following heavy flooding by Hurricane Sandy in Belmar, New Jersey, November 1, 2012. (Photo: Michael Reynolds)The fire in Breezy Point destroyed between 80 and 100 houses in the flooded neighborhood. (Photo: Fox News)

-

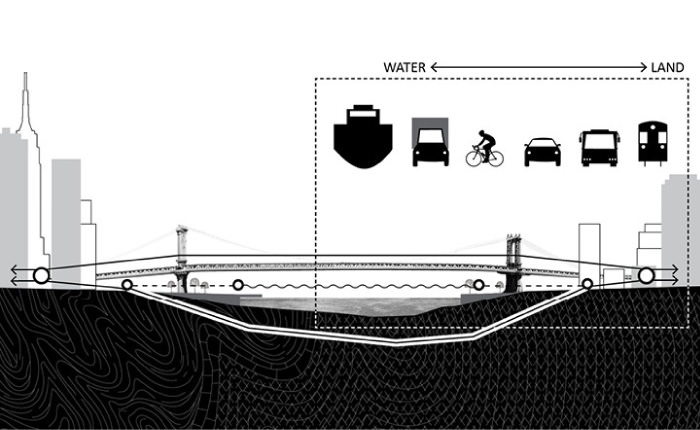

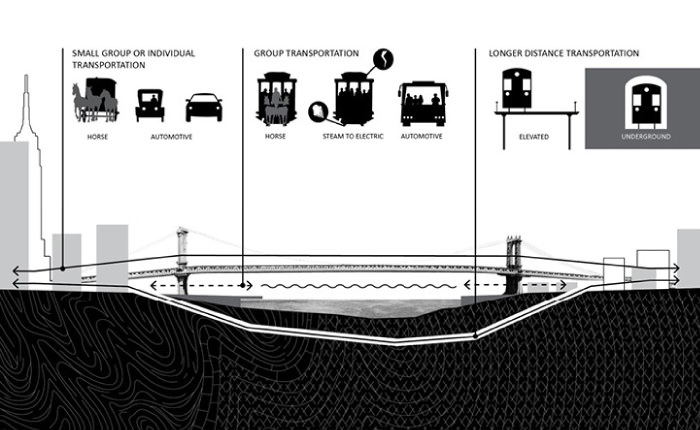

Analysis diagrams by dlandstudio for the exhibition “Glimpses of New York and Amsterdam in 2040,” in which Susannah Drake showed ideas for a Hybrid Urban Base, a new intermodal civic and transportation system. (Image courtesy dlandstudio)

The Dutch strategy of planning for 10,000 years into the future is necessary to protect not only their built environment but also their GDP, 68 percent of which is derived from land that is below sea level. Given the value of physical property in the Northeastern United States and perhaps the even greater value of keeping one of the largest economic engines in the world running, New York needs to radically rethink its approach to protecting its resources. Flood gates, similar to those forming part of the MOSE scheme being constructed in protect Venice, are a simple but expensive solution that the general public may understand and approve of, but their use could trigger a set of extraordinary ecological and socioeconomic impacts down the line. Volatile Infrastructure The term “infrastructure” developed in the World War II era in reference to military logistical operations. In today’s cities, our infrastructure facilitates, enables, and distributes the exchange of goods and services. Advances in technology in the aftermath of the industrial revolution such as the pure engineered solutions of large concrete structures, including storm culverts and sea walls, were seen as superior to the “softer” historical precedent. As was visible in the aftermath of Hurricanes Katrina, Irene, and now Sandy, these inflexible, engineered systems can fail with catastrophic consequences as the severity, frequency, and intensity of storm events increases.

-

It is time to rethink twentieth-century engineering and consider options that can again work in concert with the natural environment.

Understanding how physical geography, ecology, and climate function is critical to the development of new types of infrastructure that are more responsive to the forces of nature. The idea of using natural systems to provide public amenity and health benefit is not new. For example, Frederick Law Olmsted used tidal flows to reduce pestilence and pollution in the Back Bay Fens of Boston in the nineteenth century. Yet Olmsted did not rely solely on plants and fauna to achieve his goals; he employed highly engineered systems, hidden from public view, which improved the effectiveness of his designs without detracting from their beauty.

Olmsted’s strategies, however, could only go so far to manage increased waste. When English plumber Thomas Crapper refined and promoted the flush toilet, he surely had no idea his work would trigger a cascade of events that would lead to the degradation of waterways across the globe some 150 years later. Rapid urbanization in the US in the latter half of the nineteenth century created the need for collective management of sanitary waste in cities. In search of innovation, the US looked to France and Germany, where a new form of infrastructure – the combined sewer – was already being used to manage increased sanitary waste resulting from the ubiquity of the flush toilet. Combined Sewer Outfalls (CSOs) release a combination of surface water runoff and sanitary sewage into our waterways when there is too much effluent for the treatment plants to manage.

New York City, like 772 cities across the US, has a combined sewer system. In New York’s case, in even a light rain, sanitary and storm wastes combine and flow into New York Harbor. Virtually all US cities with combined sewer systems are in violation of the federal Clean Water Act, whose rules, Downtown Manhattan underwater. (Photo: Susannah Drake)

Downtown Manhattan underwater. (Photo: Susannah Drake)»To find solutions to the problems of storm surge and antiquated, inadequate, and unprotected infrastructure, political leaders, planners, and designers need to look to nature for part of the answer.«

-

Flooded Chelsea on Monday night after Hurricane Sandy. (Photo: Susan Hamaker / japanculture-NYC)

-

enforced by the US Environmental Protection Agency and state regulatory bodies, are forcing cities to develop strategies to clean and process storm water runoff. Unlike Hurricane Irene in 2011, Hurricane Sandy was not a small storm.

At the height of the hurricane, the region was flooded by exceptionally high tides and storm surges, putting tremendous pressure on the combined sewers and flushing contaminated waste water — from toilets, storm drains, streets, and factories — into New York Harbor. Even small waterways, like Brooklyn’s Gowanus Canal, overflowed their banks, spreading water contaminated with both bacteria and toxic chemicals across residential streets, sidewalks, yards, and into houses and businesses.

Nature is (part of) the answer

In the US we need to look further into the future, taking advantage of the great opportunity to develop new innovations based on our

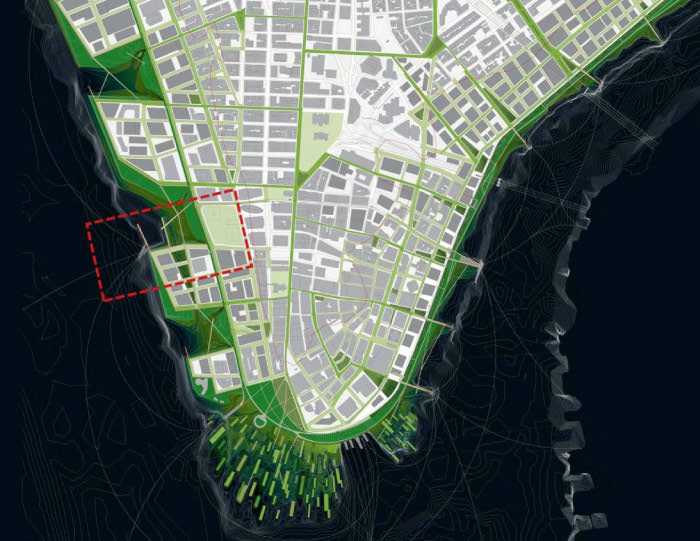

Proposed protective wetlands around the tip of Lower Manhattan from the “Rising Currents: A New Urban Ground” exhibition at MoMA. (Images: dlandstudio)

-

geographic diversity. In New York, highways, train yards, and public housing are often located in flood plains along the post-industrial waterfront, where the land was cheap, available, and in some cases already publicly owned. To find solutions to the problems of storm surge and antiquated, inadequate, and unprotected infrastructure, political leaders, planners, and designers need to look to nature for part of the answer.

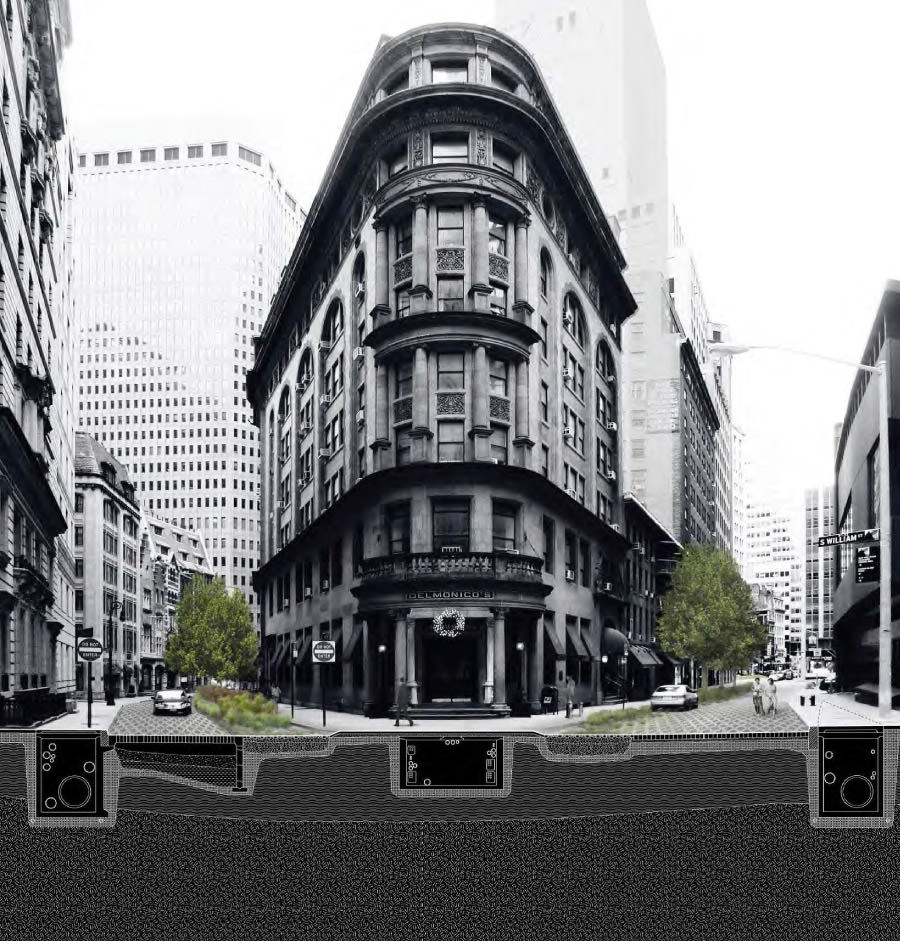

The function of barrier reefs, salt marshes, and cypress swamps, depending on the climate of an area, can inspire new models for ecosystem management. Gradual buffered waterfront edges and barrier islands can weaken wave energy, contain saltwater flooding, and make healthier habitats that also help store carbon. Planning for the periodic swells of rivers and streams could well force the relocation of homes, roads, and businesses unless we adapt the architecture (buildings) and landscape architecture (infrastructure and outdoor space) by rethinking how the landscape absorbs water, the materials of construction, the relocation of mechanical systems, and access. Zoning jurisdiction should consider topography so that buildings and infrastructure in flood plains have specialized design. Roads built of porous materials can soak up water, and highway trenches can be covered with parks that clean the air and provide recreation space, and our shorelines could be re-designed with an alternating combination of hard edges to facilitate commerce and softer edges to protect valuable upland real estate. Critical infrastructure below grade should be protected from inundation by saltwater. Whenever and wherever possible, other infrastructure should be relocated above the highest potential flood levels.

As we develop the means and methods for managing increased and more frequent storm impacts, we have a tremendous opportunity, some 40 years after the Clean Water Act became law, to manage the day-to-day loads and the exceptional circumstances with holistic new gray/green»We’ve got to rethink where you build houses, where you build schools, where you build highways and how you build them. We have to redefine our flood plains.«

-

engineered approaches. The USEPA estimates that $94.9 billion will be needed for storm water management and CSO mitigation, to bring cities into compliance with the law. At the same time, over 50 billion dollars is the projected sum needed to rebuild New York City alone. Resources to address these issues should be combined. Need for immediate action to help people displaced by the storm is important, but as we move forward it is critical to assess whether certain sites are suitable for development. Vulnerable areas should be designated as ineligible for mortgages and insurance.

Aggressive long-term planning

We can’t contain nature to the extent believed in the last century; long-term, large-scale planning and actions that reduce our impact on the land, work in concert with natural systems, and enable new types of ecological and socioeconomic exchange are necessary if we are to lessen the impacts of nature’s force. The very survival of this city and all cities that exist at sea level around the

Adapted infrastructure with private and public infrastructure moved under sidewalks, freeing up street surfaces – 28 percent of the city by land area – to be water-permeable surfaces. (Image: dlandstudio)

Adapted infrastructure with private and public infrastructure moved under sidewalks, freeing up street surfaces – 28 percent of the city by land area – to be water-permeable surfaces. (Image: dlandstudio) -

Lower Manhattan in the dark after the Hurricane. (Photo: Iwan Baan)

-

world depends on their becoming resilient to climate change and increasingly numerous and powerful storms. Urban resilience requires an aggressive, multifaceted approach to both the adaptation of existing infrastructures and the development of radical new systems. Moving forward, we must employ a hybrid methodology that manages the force of saltwater storm surges by expanding both engineered and natural softening of select waterfront edges while also expanding our approaches to upland fresh stormwater management.

Mayor Bloomberg and Governor Cuomo have spoken with urgency about our mission. Peter Shumlin, Governor of Vermont, which was devastated by last year’s Tropical Storm Irene, said, “Any objective scientist will tell you that as a result of climate change, we’re going to get more intense storms in New England. We’ve got to rethink where you build houses, where you build schools, where you build highways and how you build them. We have to redefine our flood plains.” We must act now to aggressively design and build pilot projects, test materials, challenge assumptions. We need to create a new natural urbanity.

Photo: Iwan Baan

Photo: Iwan Baan

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Architecture starts when you carefully put two bricks together. There it begins.«

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents