-

Arved von der Ropp (born 1943) started to work as a photographer in 1960 together with his mother Inge von der Ropp. He says, to visit Gottfried Böhm’s city hall in Bensberg (1964-68) was like a revelation, especially compared to other architecture around that time.

seier+seier: Architect married to an architect in Copenhagen.

www.flickr.com/people/seier/

GOD’S

CONCRETE

ROCK

...and exactly 40 years later. The only visible change is the light grey paint that has been put on the leaking roof. (Photo: seier+seier, 2008)

The pilgrimage church Mary, Queen of Peace, rising from the medieval town of Velbert-Neviges in 1968... (Photo: Arved von der Ropp)

Gottfried Böhm’s

church in NevigesText by Florian Heilmeyer

Photos by Arved von der Ropp , seier+seier -

Aerial, ca. 1970. (© Picture archiv of the city of Velbert)

-

»It’s easy to imagine that in 1968, when it was inaugurated, not everyone was happy with this giant concrete (Catholic!) church.«

The small German town of Neviges is home to about 19,000 inhabitants and a spectacular concrete structure, which looms over the narrow medieval alleys. This is the pilgrimage church called Mary, Queen of Peace, built in 1968 and designed by German architect Gottfried Böhm, which continues to hold a special place in many people’s minds – including architecture and Catholic pilgrims alike. Why did this bold expressionist building land in this small, medieval (and Protestant) town?

It all began in 1676 in the small German town of Dorsten when the Gray Friar Antonius Schirley knelt down in front of a painting of the Virgin Mary, just as he did every day. Yet on this particular day a voice suddenly spoke to him: “Bring me to Hardenberg. There I will be praised.” The voice alluded to certain healing powers, which convinced the Friar to do as he was told. He brought the Virgin Mary canvas to the newly founded Franciscan mission in the nearby town of Hardenberg-Neviges. A few years later Ferdinand von Fürstenberg, the Prince-Bishop of the region, fell ill nearby and traveled to the small chapel where the Virgin’s image had been placed, where he was miraculously cured. This was the birth of the Catholic pilgrimage to Neviges.

Infrastructure grew along with the growing numbers of pilgrims: a cloister was built next to the chapel, and the chapel was replaced by a church. In the nineteenth century the monks started to expand into surrounding property, adding processional paths, and creating a “Hill of Mary” and a “Hill of the Cross,” including grottoes, groups of statuary, and smaller chapels. By 1740, about 20,000 pilgrims were coming to Neviges every year – and by 1954 the number had grown to about 300,000. Most of the pilgrims stayed overnight, turning the pilgrimage into the main economic engine of the area. This also encouraged the Protestant majority in this region to stay mostly tolerant of the Catholic pilgrims.

Gottfried Böhm's original charcoal drawing from 1968. In his drawings, Böhm usually included a pair of spectators representing himself and his father, Dominik Böhm, who was also a famous church designer. (© Deutsches Architekturmuseum, Frankfurt am Main)

-

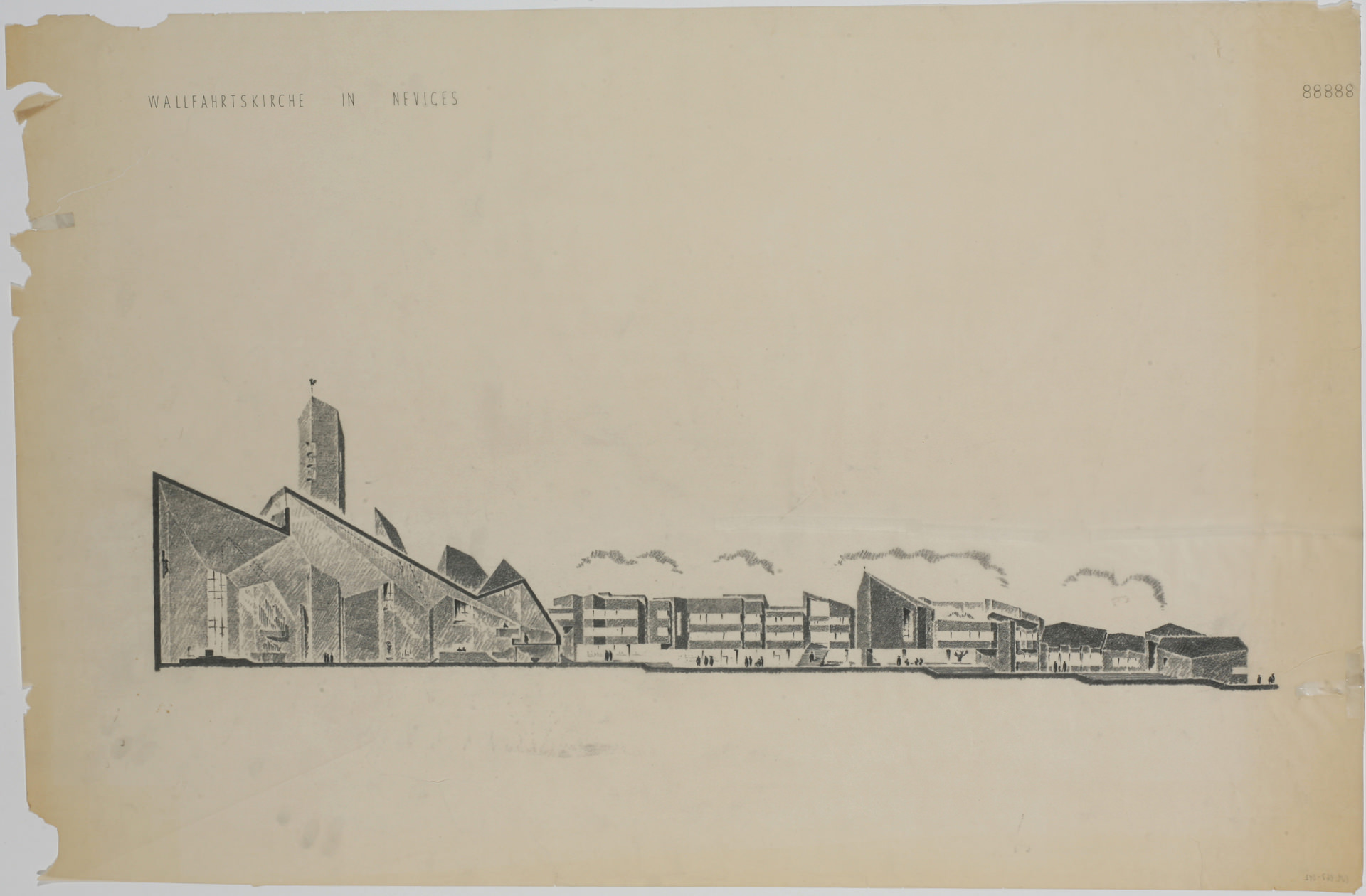

Long Section through the church and the Via Sacra, showing how important the connection of outside and inside spaces were to Böhm. The concrete church was actually intended to be more like a tent-like structure spanning over the end of the pilgrimage route. (© Deutsches Architekturmuseum, Frankfurt am Main)

-

Corbu or Mies?

Plans for a bigger and more appropriate church had been around since the beginning of the twentieth century, but economic and political changes impeded the start of construction for almost half a century. It was not until 1959 that the Diocese of Cologne invited 17 teams to participate in an architecture competition. Meanwhile the plans had grown to such an extent that the design brief asked for the second largest church north of the Alps (only the Cologne Cathedral is bigger), a dome that could not only hold about 3,000 people, but also included a kindergarden, a museum, and a few apartments exclusively for the nuns amongst the pilgrims.

In his essay “The Multi-layered Concrete Rock” (in: Gottfried Böhm, Jovis Publishers, Berlin 2006), Karl Kiem describes that all competition entries could be placed stylistically into two (modern) baskets. The new structure was envisioned as either a functional square or an organic, nature-inspired figure: “[There was] basically the choice between a functional modernism modeled on Mies van der Rohe’s IIT Chapel in Chicago (1952) and others that were more freely formed based on Le Corbusier’s pilgrimage chapel in Ronchamp (1955).” We can only guess whether Le Corbusier’s Ronchamp, which lies about 500 kilometers south of Neviges, served as an inspiration for Gottfried Böhm’s winning design.

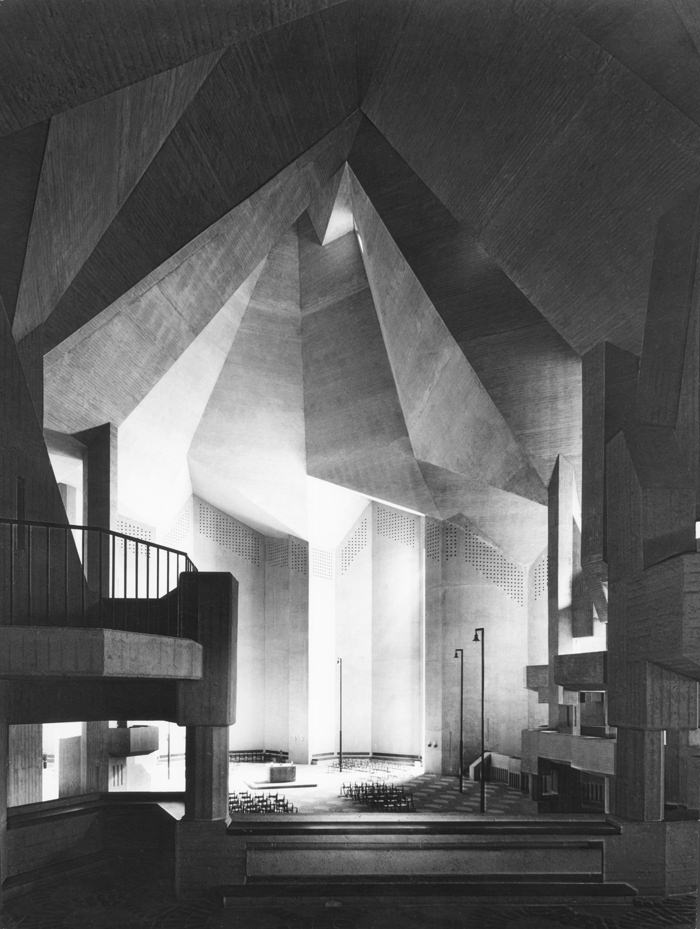

The space of the main nave roars spectacularly upwards. But underneath the Via Sacra is unspectacularly leading right up to the main altar: Böhm continued with the same paving and the same street lamps from the outside to the inside. The open gallerys are like small houses with balconies surrounding this "market place“. (Photos: Arved von der Ropp, 1975).

-

A nun’s pilgrimage (Photo: Arved von der Ropp, 1975).

-

The glass-stained windows of the chapel show roses, a motif commonly connected to the Virgin Mary. Böhms architecture seems to connect effortless postwar modernity with expressionism and a dose of German romanticism. (Photos: Arved von der Ropp, 1975).

-

The decision in favor of Böhm’s proposal was also made because he was the only architect to include the existing topography as part of his scheme. While the other proposals suggested leveling the entire area, Böhm placed the dome on the highest point of the slightly sloping site, creating a promenade for the pilgrims that continuously rises upwards with a few stone steps every couple of meters. This gesture connects the church to the town and the pilgrimage path, making the dome the enclosed end of the open-air pilgrim’s route: Approaching the church, the path winds through the narrow alleys of the medieval town, spiraling around the “concrete mountain” which only appears every now and then over or between the old buildings of the city center. This continues until one enters the slightly curved promenade and – finally – the church itself.

It’s easy to imagine that in 1968, when it was inaugurated, not everyone was happy with this giant concrete (Catholic!) church rising in the northeast of Neviges. It was certainly an intrusion. Böhm’s structure has been compared to all sorts of things: a bunker, a tent, a fortress, a rock with a giant cave and a crystal. The expressive form of the roof might also be seen as a protective coat, a metaphor that is often found in the design of churches dedicated to the Virgin Mary. Gottfried Böhm has never explicitly explained his inspirations, so we might assume that he intended for his design to be open to all of these interpretations.

Photo: seier+seier, 2008

-

However one interprets the form, it cannot be considered completely alien; It is not an isolated monolith, but rather a greyish crystalline rock – God’s rock! – placed in front of the green hills of Neviges. It seems like a logical conclusion that evolves out of the slowly changing spaces along the route. The church is both connected to and set apart from the town by a modern version of a Holy Precinct, including the nuns’ residences and the kindergarten, which are placed to the left and right of a via sacra directly in front of the church’s main entrance. This kind of attention to context and details continues inside. Of course, at first the central room makes freezes one in awe after passing the rather small and modest entrance. All of a sudden everything about the space seems to roar up towards the sky until, high above, and one’s gaze comes to rest on the bottom side of the roof, the many-folded structure of which is visible inside. The room feels much bigger than you would expect from the outside. But then one starts to discover all these familiar materials and structures: Böhm used the same paving and street lamps inside as outside, so there is continuity in the atmosphere of the exterior and interior spaces, beneath the 7,500 cubic meters of the concrete roof’s structure. Together with the open concrete galleries this looks like an abstract version of the small-scale town that one has just passed through, like a light covered, very robust marketplace.

Photo: seier+seier, 2008

-

»Most of the pilgrims stayed overnight, turning the pilgrimage into the main economic engine of the area.«

The robust and scant surfaces and materials inside have remained their quality.

(Photos: seier+seier, 2008) -

Uncanny and Exhilarating

Today it seems that the people of Neviges have developed pride in “their” church, which remains a considerable sensation, not only in the context of Neviges but also worldwide. It’s like an open house that attracts many different visitors: believers and non-believers, Catholics and Protestants, pilgrims of the Virgin Mary and pilgrims of architecture. The church is widely considered Gottfried Böhm’s masterpiece, although he built some 60 other churches most of which are also beautiful and impressive buildings. But never before or after he was able to develop such a convincing gesture and comprehensive design, from the exterior spaces to the chairs and the bright colored windows of stained glass. When he was awarded with the Pritzker Prize in 1986, the laudation seemed to make direct reference to the church in Neviges: “His highly evocative handiwork combines much that we have inherited from our ancestors with much that we have but newly acquired — an uncanny and exhilarating marriage.”

Although the construction was highly experimental in the 1960s, Böhm’s building has not required any significant changes until today. Since the interior cannot be heated (it was meant as a summer church for the pilgrims), a smaller, warmer chapel room has been created inside. Böhm had designed freely movable chairs for visitors, which are now anchored in defined rows. The roof had to be fixed after water damage occurred in the 1970s, and a light grey paint was applied which disturbs the general impression of the monolith for the keen-eyed pilgrim as the other walls have meanwhile turned a much darker grey. These days, the monks – together with the 92-year old Gottfried Böhm – are conducting tests for an alternative roof construction strategy. A covering with lead plates is currently being discussed. Böhm, who still lives in Cologne, has remained closely connected to his building and continues to visit it regularly.

Photo: seier+seier, 2008.

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Don‘t fight forces, use them.«

Richard Buckminster Fuller

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents