-

Squish Studio, Fogo Island, Newfoundland, Canada, 2011.

Interview By Rob Wilson

-

Todd Saunders is best known for a number of small exquisite buildings and structures that sit like specs of pristine ur-architecture amid vast wild landscapes – from Norway’s west coast to his celebrated series of Fogo Island studios, off Newfoundland. He grew up in Canada, studied ceramics and environmental town planning at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design in Halifax (he had originally wanted to study sculpture and ceramics but says he “didn’t have the balls to do it”), followed by a Masters in Architecture at McGill University in Montreal. In 1998 he opened his office in Bergen – which is Norway’s second largest city, but somewhat an off-place in many ways.

So when we caught up with him, we asked about this distinctively “off-space” oriented trajectory of his practice thus far.You’re from Canada, how did it come about that you opened your office in Bergen? It’s somewhat off the beaten track for an architect looking to relocate abroad!

Well, yes. It’s in the middle of frigging nowhere. But the city is so nice in itself. What I always say is that it’s a good place to live but a shitty place to work – except for my colleagues of course! – there’s nothing going on architecturally here. But it does have all the advantages of living in a small town: people watch out for one another, and it’s easy to get out into nature. I first visited Norway when hitchhiking to Moscow as a student and then decided to come back. I was going to live in Oslo but then I came up here as it fit my lifestyle – I could go kayaking and do backcountry skiing, race mountain bikes – though of course now that I have kids I don’t do any of that stuff any more!

Todd Saunders. (Photo: Jan Lillebø)

Todd Saunders. (Photo: Jan Lillebø) -

But originally I was going to try it out for six months. At first it was like survival, I had no work but I had a woman here, so I realized I wanted to stay.

I was teaching at the architecture school in Bergen and trying to build up a practice. I was designing and doing anything that I could get my hands on – like playgrounds – and also working with a carpenter every second week, doing odd jobs, because I didn’t know how long I was going to be here. I built a chicken house, and worked with the students at the architecture school, and all the time I was learning all this stuff – how to build in Norway, the price of material – without realizing I was learning. So I pieced together a living and for the first few years I was super-happy. Of course when I look back at it, it was a shit load of work. Corner of Todd Saunder’s office. (Photo courtesy Saunders Architecture)

Corner of Todd Saunder’s office. (Photo courtesy Saunders Architecture) -

»At first it was like

survival, I had no

work but I had a woman

here, so I realized

I wanted to stay.«Hardanger Retreat, Kjepsø, Hardanger Fjord, Norway, 2003

-

Lookout point, Aurland, Norway, 2005. (Photo: Nils Vik)

-

So how did you start your architecture practice?

Well I met another guy who was in the same situation: Tommie Wilhelmsen. We were frustrated young architects with no projects. So we saved the money from a few commissions doing small stuff, then bought a piece of land and built this cabin up at Hardanger for ourselves, working with one of our students who was a carpenter. Then we got a few pictures taken by Bent René Synnevåg, who we’ve worked with on all our projects since – he just went up there for an hour or so, didn’t really take it too seriously,. But it was at the time when the media and the internet were coming together and it was suddenly easier to get things out.

So the project got wide coverage and acted as an amazing calling card?

Yes, the funny thing in retrospect is: if there had been no internet, we probably wouldn’t have gotten that much exposure. We would just have been these recluses living out on the west coast in the middle of nowhere – no one would ever have known about us! Yet suddenly it was possible. We could be based anywhere and work anywhere. We just did a house in Polynesia and we’re doing a really nice project in Istanbul which is quite large, and a hotel in Canada – all this stuff because people read about us.

So after the Hardanger Retreat came the Aurland Lookout…

Yes. When we were doing Hardanger we got a call to compete for a lookout structure on one of the national tourist routes. They invited all the established architects and then they invited us as the young unknowns – and we won!

Lookout point, Aurland, Norway, 2005

Lookout point, Aurland, Norway, 2005 -

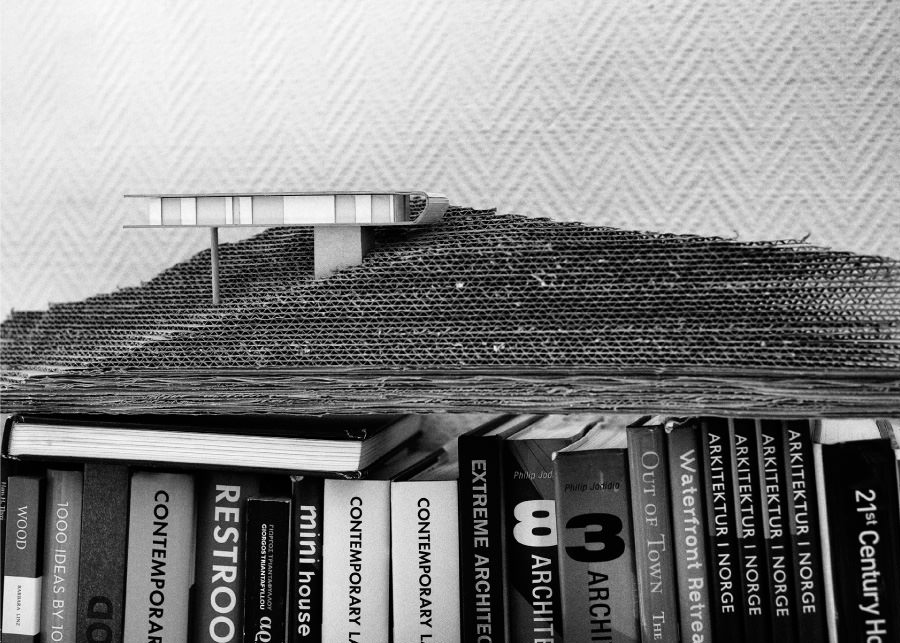

Map of Fogo Island, Newfoundland, showing the relative positions of the six artists studios and the Fogo Island Inn, which are being built by the Shorefast Foundation to provide residencies and a sustainable focus for culture and employment on the island. Of these, four studios have already been completed and the Fogo Island Inn is under construction. Two studios: Short Studio and Fogo Studio, shown feint in the key, are not yet built.

1 FOGO ISLAND INN

2 LONG STUDIO

3 SQUISH STUDIO

4 SHORT STUDIO

5 BRIDGE STUDIO

6 FOGO STUDIO

7 TOWER STUDIO

-

Fogo Island Inn under construction.

Fogo Island Inn under construction. -

What I like is the sense of humor in your structure: how the handrails curve down like in a swimming pool – yet here it’s over a vertiginous drop. It’s almost surreal.

Tommy and I are both afraid of heights – so there is the quirkiness of the glass barrier at the end which is not vertical but it’s tipped outwards. When you come to it you have to trust it. Lots of people don’t go out that far! Maybe you’re right: I suppose there is a bit of humor in it.

And then more recently another “off-place” project came along: Fogo Island. How did that project come about?

Well the client, Zita Cobb, established the Shorefast Foundation as she had this idea to invest in culture on the island, which is off Newfoundland

»It sounded like a

dream project from

when you’re at

architecture school!«where she grew up. It’s quite remote as its economy was based on the fishing industry but there’s none there anymore. Everyone is leaving, especially the young ones, and she wanted to inject something into the mix to keep the island alive.

She could have made a clothing factory. But she had this idea that money disappears while culture does not. So she came up with plans for an art foundation instead, offering residencies on the island. She wanted to find a local architect for the project when she read an article about me in a Canadian newspaper – I grew up in Newfoundland – and she called me, actually whilst I was paddling my kayak! It sounded like a dream project from when you’re at architecture school!

It’s a series of six artists’ and writers’ studios, -

A perfect kind of bleak: Long Studio, Fogo Island, 2010

-

all sitting directly in the landscape, with a linked hotel, the Fogo Island Inn. The island is pretty much the same sort of place that I grew up in, so I didn’t have to do research. A lot of it was intuitive: the smell, the wind, the weather, I knew everything about it. There was no guesswork.

How did you choose the sites?

Good question. The Canadian government owns most of the property near the ocean on the Island. The aim was to find a variety of different situations and environments. We originally suggested about ten possible sites, and discussed it with the people living in the towns, adding their further suggestions.

Do you have a favorite site?

I think the writer’s studio – the Bridge Studio, like a box – is my favorite. I called it the ugly cousin after we designed it. We wondered if it was too simplistic. But I like it.

The constant drama of light and landscape from morning to evening: Squish Studio, Fogo Island, 2011.

»A lot of it was

intuitive: the smell,

the wind, the weather,

I knew everything

about it.« -

The Bridge Studio: from the bridge to the entrance, to the white yet cosy, timber-lined interior. Nick-named “the ugly cousin” by Todd Saunders for its uncompromisingly simple box-like shape, it is his favorite of the six studios.

-

The next stage of the project is the hotel: the Fogo Island Inn, which is more for regular people coming to the island, and presumably for local employment?

It’s more a business than the artists’ studios. But the way we’ve tried to do it is that there is almost no divide between the studios and the Inn. So there is an art gallery at the Inn, a nice library and a small digital film-house – basing the interior on old film-houses in New York to get that atmosphere.

So the Inn is almost like a mini art-center, as well as a hotel?

That’s a good way of describing it. We are trying to do more a kind of anti-hotel.

From afar the forms of all the Fogo Island projects look very contemporary.

Yes, but they are very rooted in the place.

The Tower Studio is positioned out on a long peninsula, so as people walk or drive by, they see it from all directions, gently twisting far off.

The Tower Studio is positioned out on a long peninsula, so as people walk or drive by, they see it from all directions, gently twisting far off. -

Up, down, and all around. The interior of the Tower Studio

»I didn’t want the artist to be like a dancing

bear living out in the studio. They can then be

in the community and get to know people.« -

»It has a different personality

depending on your viewpoint

and is not just a static object in

the landscape.«Tower Studio, Fogo Island, 2011

-

Todd Saunders founded Saunders Architecture in 1998. Saunders was born in Canada and has lived and worked in Bergen since 1996, following his studies at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design in Halifax and McGill University in Montreal. He combines teaching with practice as he teaches part-time at Bergen Architecture School. He has also lectured and taught at schools in Scandinavia, the UK and Canada and was visiting professor at the University of Quebec in Montreal.

All the material and construction is traditional to Fogo Island or at least Newfoundland. So I like this expression “strangely familiar:” when one of my uncles saw one building, he said “that’s a little different.” But when he got up close, everything was familiar to him in the construction.

In some of the studios you can spend the night, but in general each artist actually lives in an old house in the town. These old traditional houses are so simple and, to my mind, so beautiful. I didn’t want the artist to be like a dancing bear living out in the studio. They can then be in the community and get to know people.

What is your process of design? How do you conceptualize your work?

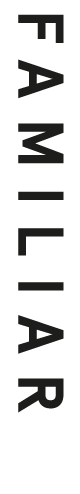

We work with a lot of physical models at first – but rather than form following function, we fit the form to the landscape.

»Out in the landscape,

you really appreciate

things. You shouldn’t

actually build there. You

can’t really improve it.«So if you take the Tower Studio, for instance, it’s out on a long peninsula, so people see it from all directions. If you’re walking or driving by, you see it gently twisting far off. It has a different personality depending on your viewpoint and is not just a static object in the landscape.

So in general where does your connection with landscape come from?

I grew up with hippy parents and we spent our summers in a little house in the middle of nowhere with no electricity and no plumbing, and that was one of the best times of my life!

Maybe that was formative in why I respect beautiful places so much. Out in the landscape, you really appreciate things. You shouldn’t actually build there. You can’t really improve it. You know you get a commission in one of these places and just hope that you do not screw it up afterwards!

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Less is a bore.«

Robert Venturi

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents