-

The Mystery

Train Station

of CanfrancMarc Chagall, Nazi Gold and Doctor Zhivago! It all comes together at a train station that is as grand as forgotten.

Text by Myrta Köhler

The “Blue Staircase” of Canfranc. Photo: Stefan Gregor, 1998

-

In the presence of King Alfonso XIII of Spain, the central train station of Canfranc was inaugurated on July 18, 1928 amid general rejoicing. Progress had finally reached the languid Pyrenees. A symbol of economic upswing, the station on the border between France and Spain was to connect the Iberian Peninsula with the rest of Europe. But after a brief period of splendor, the stone giant fell to ruin. The building that was long ago called the “Titanic of the Pyrenees,” is now finally going to be resurrected.

In the Valle del Aragón you can practically hear the grass grow. It flourishes between the railroad ties, obscuring the rails. The sight of an enormous train station building looms above them: a monument from another world, as imposing as the nearby mountains, and perhaps even more quiet and enchanting than the valley. Forlorn train cars covered in graffiti rest atop deserted train tracks. The windows of the main building are shattered, the doors locked. No trespassing.

The huge and derelict train station of Canfranc, also called the “Titanic of the Pyrenees” is located almost on the border between France and Spain. (Photo: Matthias Maas)

-

»From Canfranc, the train drove straight into freedom!«

Photo: Matthias Maas

Photo: Matthias Maas

-

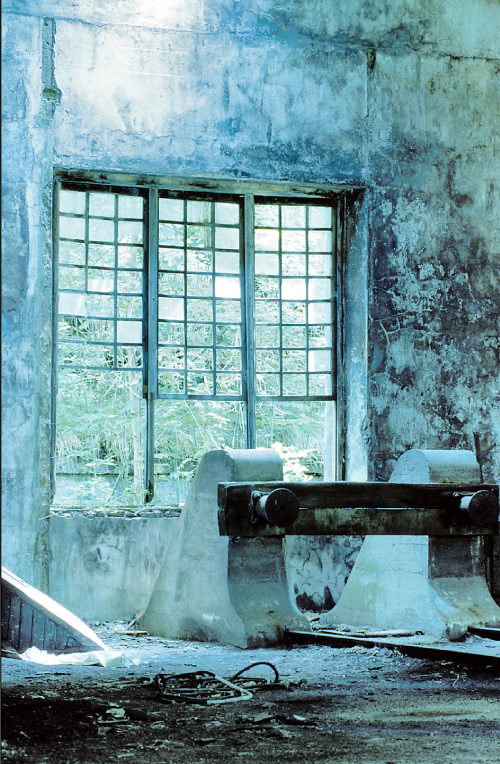

Photo: Stefan Gregor

Photo: Stefan Gregor -

No trains today. (Photo: Stefan Gregor)

No trains today. (Photo: Stefan Gregor) The glory has departed: (Photo: Stefan Gregor)

The glory has departed: (Photo: Stefan Gregor)And yet they come: tourists, weekenders – and photographers. Where there is a will, there is also a way inside the building. Matthias Maas, a photographer from Würzburg, describes his first visit in 1996: “It was dark, cold and rainy – a real graveyard atmosphere. Terribly uninviting.” Inside it was clammy and damp, pervaded by the smell of mold. But he forced himself to unpack the camera – and was instantly spellbound. Together with his partner, Stefan Gregor, he would return regularly to document the giant’s demise.

The contrast between the majestic building and the sleepy municipality of Canfranc is staggering. Only a handful of people live here – far too few for a train station of such magnitude. The three-story central building is an eclectic construction nearly 250 meters in length. It holds not only the cavernous ticketing hall embellished with stuccoed ornamentation, but also an infirmary, a customs office, and a grand hotel. And all for what? -

In the mid-nineteenth century, at the pinnacle of the Industrial Revolution, the route from Zaragoza (Spain) to Canfranc to Pau (France) was to be the shortest possible route linking the centers of northern Spain with those in southern France It was not until 1915 that rivers were diverted, railway embankments backfilled, and the 7.8 kilometer-long Somport tunnel was plowed through the Pyrenees Mountains. The excavated granite provided the foundation for the Canfranc station, realized by architect Fernando Ramírez de Dampierre. As an international hub, it would herald the arrival of modernity in the Pyrenees and transport the glory of a small region far beyond its own borders.

But a major opportunity was missed: Spain refused to exchange its broad-gage railways for the standard-gage rails used in the rest of Europe, because of the possibility it would encourage an invasion by France. Therefore, goods as well as people had to change trains in Canfranc. An operational delay was unavoidable. There were long travel times due to the extreme inclines and narrow curves. The line also suffered considerable financial loss because of politically induced stoppages: from 1936 to 1939, because of the Spanish Civil War, and then again from 1945 to 1948. On top of this, the route was never used to capacity and was thus destined for eventual economic failure.

»The train station is a European symbol that never really had a chance to live.«

-

In the train shed. Photos: Stefan Gregor, 1998

-

The Hub of History – and its Decline

Still, Canfranc did experience a rather macabre heyday during World War II. The Third Reich exported 86.6 tons of gold via Canfranc to Spain and Portugal – this included “Nazi gold” – tooth fillings and jewellery stolen from murdered Jews. In return, Germany received what it urgently needed for its arms industry: tungsten.

It was not only the Nazis who flocked to Canfranc during the war, but also the secret services of various nations and refugees. In 1940, artist Max Ernst escaped to the USA along this route. Marc Chagall settled here for a time as well. But why choose such a strenuous path through the mountains? Ramón J. Campo, editor of the Spanish newspaper Heraldo de Aragón, explains: “Canfranc was not occupied by the Germans until November 1942 – they took Irún on the coast much earlier,” he writes. “From Canfranc, the train drove straight into freedom!” This not only applied to those fleeing the Hitler regime; ironically, after the war, German soldiers escaped from the Allies through the Somport Tunnel.

Having seen such turbulent times, Canfranc should have received plenty of opportunities to recover. After the war, however, the train station was only a ghost of its former self. As the backdrop for the film Doctor Zhivago, the Canfranc colossus again made headlines – but then came its coup de grâce. In 1970 on the French side, a freight train derailed, causing the collapse of the bridge at l’Estanguet. This brought an end to the international rail connection. A bus line was established between Oloron Sainte Marie and Canfranc for passenger transport; today, cargo from France is delivered by truck and then loaded onto trains at Canfranc. On the Spanish side, a regional train attached to a single locomotive passes twice daily – it stops at a provisional platform near the street. The old train station towers behind have fallen into disuse. -

»Evidently the place was also frequented by dealers and junkies – they noted on the walls where to find the best drugs.«

The hotel’s foyer. (Photo: Stefan Gregor, 1998)

-

Then again, perhaps the station was not entirely unoccupied. Matthias Maas relates how people were “living” under the roof, well into the nineties: “Sometimes I heard steps above me, but I never saw a face. From the side of the unused French tracks you could sometimes see laundry hanging out to dry.” Stefan Gregor added, “An interpreter translated some of the graffiti for us. Evidently the place was also frequented by dealers and junkies – they noted on the walls where to find the best drugs. Many of them also slept here – there were mattresses lying around, with piles of excrement in between ... not a comfortable place to be!”

Indeed, there is little left of the comfort of the formerly grand station hotel: the paint on the doors has peeled, the locks rusted. The stucco along the stairs has fallen off, the banisters collapsed. “In winter there were icicles hanging in the stairwell,” said Maas.

above: The former customs facilities.

right: The old ticket counter in the main entrance hall.

(Photos: Stefan Gregor, 1997/1998) -

“When the temperature rose, the melted water flowed unobstructed through every floor of the building. It will be ruined by the water.” The rest of the structure fell victim to vandalism. In 2007 the train station’s periphery was closed off with barbed wire.

Train Station of the Future

For a number of years now, citizen action groups and non-profits have called for the reopening of the international junction. The greatest amount of trans-Pyrenean transport occurs by road, which is causing extreme environmental pollution due to increasing and heavy traffic. Shifting some of this to the railway could relieve the situation – and would also result in fewer traffic accidents. With today’s technology, any train-related obstacles could be remedied with relatively ease, argues Suter.

Photo: Stefan Gregor

Photo: Stefan Gregor -

Photo: Matthias Maas

Photo: Matthias MaasNumerous upgrades and renovations would have to be made to realize this goal however, including a change on the Spanish to normal-gage rails and electrification on both sides at sufficient voltage, which is more of a hindrance than anything else for contemporary international railway traffic.

If the international route were reopened, a new, smaller train station would be erected at a different location, according to Canfranc’s mayor Fernando Sanchez Morales. The large train station has already served its duty as such; current plans include its transformation into a five-star hotel. But here, too, the continuing economic crisis has left its mark: so far, only the roof has been repaired.

For the time being the giant stands, peaceful and patient. Tourists continue to visit. Busses depart from here to the winter sports destinations Astún and Candanchú. Pilgrims find their way here as well:»The train station should be a meeting place — for people who envision the future.«

-

the Spanish “Way of St. James” to Santiago de Compostela begins in Puerte de Sompor and passes by the train station. In the summer of 2010 Matthias Maas also decided to travel the route – an occasion to visit “his” train station again for the first time in several years: “It was abominable! They sawed gaping holes into the building, removed the original green painted doors and simply nailed some kind of inside doors across the openings in their place.” Additionally, the building was surrounded by concrete slabs to support the scaffolding for the roof renovation. “I think no one really understands what value the building has as a political monument. It was born from what had been a very progressive idea of bringing together two capital cities – at a time when nationalist agendas were the order of the day.” This joining aspect is very important to Maas: “The train station should not become a hotel,” he is convinced. “Here should be a meeting place – for people who envision the future.”

Photo: Matthias Maas

Photo: Matthias Maas

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»I hate vacations. If you can build buildings, why sit on the beach?«

Philip Johnson

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents