-

Culture

and the

CityOn Content

and FormText by Matthias

Sauerbruch -

Matthias Sauerbruch, curator of the Culture:City exhibition at the Akademie der Künste in Berlin, explains the project’s background and the complex pas de deux of culture and the city.

Matthias Sauerbruch. (Photo: Kalle Koponen)

-

Culture is what distinguishes us from animals. Etymologically derived from the Latin verb colere – “to cultivate” or “to care for” – in its broader sense it is understood as the sum of the traces that people continuously create and leave behind in their dealings both with each other and with their physical environments. Culture refers to the collective accomplishments of civilization, and provides, first of all, the ethical and moral context in which we operate. It reveals itself, among other things, in our political and judicial systems that define the freedom of the individual and the powers of the community. The term culture also denotes the built, the human-made environment in all its aspects. Culture manifests itself in the values by which we live our lives and the forms – the things and patterns – that surround us. We also use it to designate all those activities dedicated to the further development and ongoing maintenance of the accomplishments of civilization, such as religion and philosophy, technology, science, and art: in this, culture is always anchored in the collective. It is a distillate of mindsets, manners, conventions, and moral values. The output of any given artist or author becomes culturally relevant only in dialogue and resonance with the public sphere. In addition to its various external particularities, this distillate that is culture is, in fact, the most important

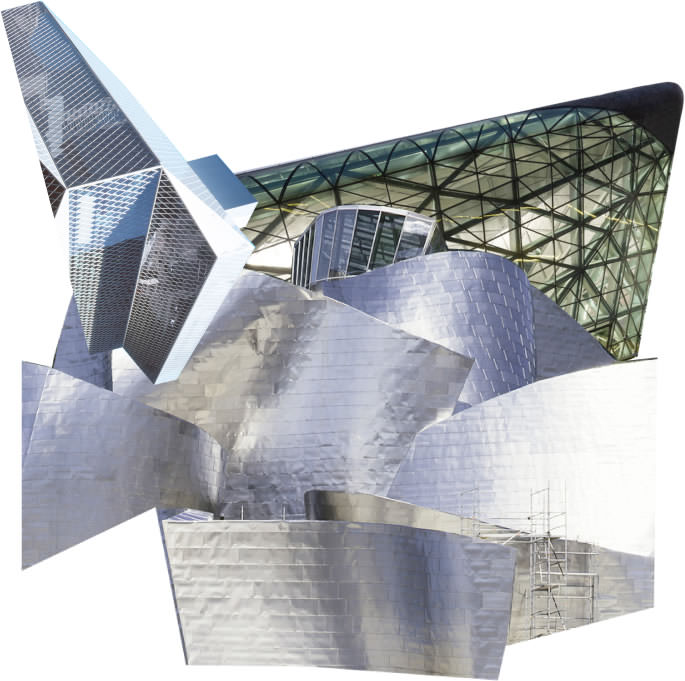

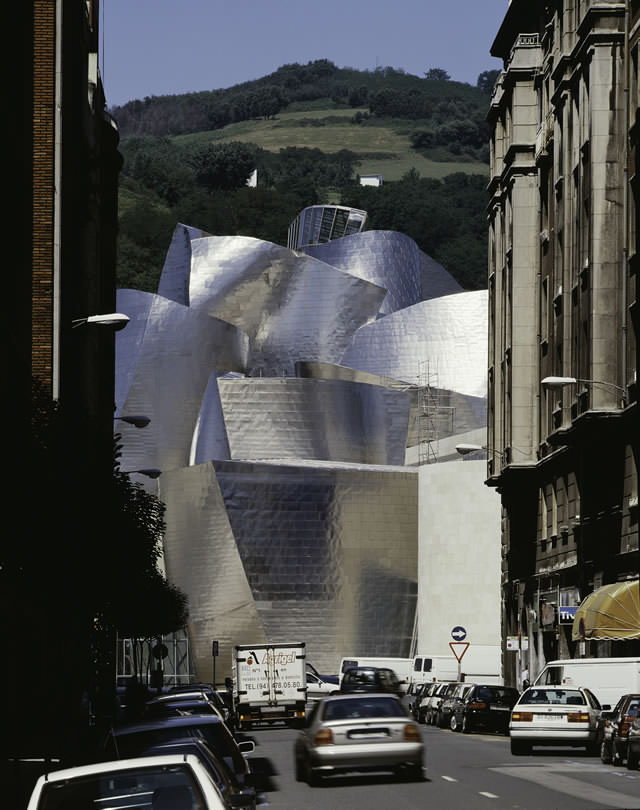

Gehry’s Guggenheim Bilbao: is this where it all started, this worldwide yearning for big-scale, extravagantly-formed cultural buildings? Sauerbruch says the focus of his Culture:City exhibition lies on the “post-Bilbao strategies that strive for closer integration of cultural institutions into the social structures and creative networks of a city.” (Photo: David Heald, © Solomon Guggenheim Foundation)

-

»A cultural building is no longer seen as the expression of common will, but as just one event among many, designed to fulfill some demand that may yet be generated.«

Michael Maltzan’s Inner City Arts project (the white building at the bottom of this picture) in Los Angeles could be seen as the opposite of Gehry’s Guggenheim. Carefully developedin stages over a period of thirteen years, it features no spectacular forms and integrates existing buildings. Initiated by a local grassroots initiative in one of the poorest neighborhoods of LA, it offers the young and the at-risk the opportunity to develop artistic skills. (Photo: Iwan Baan)

-

distinguishing characteristic for different ethnic groups, nations, and other forms of community. It is through participation in the ritual manifestations of their common culture that members of such groups develop their sense of affiliation and identity. On the other hand, culture also provides room for the fundamental human desire of self-expression. Independently of whether people’s sense of identity is primarily shaped by the collective, or, vice versa, communal culture comes into being through the creative work of individuals, it is clear that culture makes the space for the development of the individual as it simultaneously defines its limits.

The City and the Loss of the Public Sphere

The city is many things; most of all, it is the locus of the community, if at first only one of purpose. In both form and content the city is the most public manifestation of those aspects known as culture – it embodies our cultural memory at the same time it is the place of culture’s continuous renewal. The majority of those phenomena that we connect with the idea of culture stems from elements of the city, with which they are effectively synonymous. The polis offered the agora, the bouleuterion, the temple, the theater, the stadium, as those places where the respective community’s sense of identity was created and physically manifested.

»The city is many things; most of all, it is the locus of the community, if at first only one of purpose.«

-

Peter Cook and Colin Fournier designed Graz, Austria’s new Kunsthaus as an amorphous form that starkly contrasts with the inner city. The Berlin-based architects of realities:united conceived façcade of the spaceship-culturehouse to become a giant low-resolution screen, bridging interior with exterior. (Photo: Universalmuseum Johanneum, Christian Plach)

-

Subsequently such places became topoi that, even today, color our notions of both city and culture. These developed into architectural typologies still to be found in every city, effectively consolidating the preconception that politics happens in parliament, religion in church, and culture in the theater, concert hall, or museum. Such necessary coincidence of cultural activity with institutions was already thrown into question in the nineteenth century, but, even when the generation of 1968 – in its rejection of all forms of establishment – demanded that culture should happen in the street, it was still taken for granted that this should take place in the city.

Today, culture is still seen as being located in the public realm, but – at least since the ubiquity of television – the city and the public sphere are no longer assumed to go hand-in-hand. Culture has claimed its own rather effective space in various media: on TV and across the internet, all cultural production is widely disseminated with a previously unimaginable density and impact, and is generally independent of location. Such dissemination is known as “content” in internet jargon, and it does not in any way pass through the filter of the collective. At best it expresses swarm intelligence, disappearing without a physical trace. In this way the internet would destroy the city in the same way that Victor Hugo predicted the book would destroy the cathedral, disrupting the age-old symbiosis between collective space and culture. With the loss of this tangible public space, as Richard Sennett explains in The Fall of Public Man, the specificity of public life is characterized by an increasing focus on the individual.

M9 is a museum currently under construction in Mestre, Venice, designed by Matthias Sauerbruch and Louisa Hutton. The new building connects to parts of an old cloister and an office building from the 1960s. (Image: Sauerbruch Hutton Architects)

-

»The city and the public sphere are no longer assumed to go hand-in-hand. Culture has claimed its own rather effective space in various media.«

M9, a new museum for Mestre/Venice, to be completed by 2015. Image: Sauerbruch Hutton Architects

-

Instead of the ideas and ideals of a community, it is the mental state of the individual that demands all the attention. Sennett talks of the “tyranny of intimacy.”

These developments have lasting consequences for the city (as we used to know it). Deprived of traditional content, collective spaces begin to feel like empty shells that have difficulty relating to the random collection of vested interests by which the city seems increasingly to be defined. A new (cultural) building is no longer primarily seen as the expression of common will, but as just one event among many, designed to fulfill some demand that may yet be generated. The void left by the disappearance of active public life is filled by an ever-expanding cultural industry that endeavors to satisfy our desires for some sense of self-determination and selfexpression. Culture is no longer allowed to develop – culture is manufactured, and the commercialization of this, our need for identity, is growing unabatedly, as Richard Florida explains in The Rise of the Creative Class.

Cultural Activities and Surrogate Acts

Perhaps Venice can be used as a case study to exemplify these developments. Currently some 40,000 Venetians are responsible for the upkeep of the historic city-center’s growing infrastructure to the benefit of some 20 million visitors a year. The churches and palazzi, the impressive Arsenale – all outstanding expressions of urban culture – now stand empty and have to be filled with new commercial uses, if only to stop them from falling down. To us, of course, the protection of these historic monuments seems essential, because these buildings stand as irrefutable proof of the existence of a great culture, in which we see ourselves as participants. However, it is obvious that a short encounter – say, as part of a Mediterranean cruise or a visit to the Biennale – can never be more

-

»Essentially, the city remains the most important manifestation of culture.«

Guangzhou is China’s third-largest city. In recent years it has been trying hard to change its image from that of a booming industrial town into that of a city of ecology and culture. Part of the urban transformation along the river is its new opera house, designed by Zaha Hadid Architects. (Photo: Hufton + Crow Photographers)

-

than a surrogate act. Here culture becomes a cliché, just a selling point and marketing device, the experience of which rarely goes beyond mere consumption, and doesn’t offer any impulse to contribute much in return. For the twenty million visitors that Venice attracts every year this does not present a problem, since, in any case, they will soon return to their own homes; but for the Venetians the problem is acute as their local culture becomes fully submersed under the nostalgia of their own past; thus residents are condemned either to an existence as amateur actors restaging their own history, or to being tourists in their own city. In this way contemporary Venetian culture manifests itself, if at all, either in the form of resistance to the ruthless marketing of the island, or simply in relocating itself to other, more impartial sites, such as Mestre on the mainland.

Venice is, perhaps, an extreme case, but the culture of many other European cities also finds itself in a somewhat similar process of development. Where historic fabric still exists, it becomes the scenic backdrop for rigorous commercialization. Traditional city centers line up alongside amusement parks, shopping centers, sports facilities, and commercial zones as just one of many urban events embedded in an extensive network of infrastructure. Telecommunication and unlimited mobility have blurred the traditional territories of European cities, just as globalization and structural change have modified their economic foundations.

“In the race for the fleeting attention of the internet generation,” writes Sauerbruch, “the architectural profession has also allowed itself to be tempted into ever-increasing extravagance.” Guangzhou Opera House, main auditorium. (Photo: Hufton + Crow Photographers)

-

OMA’s library offers a system of freely accessible public space spreading over all floors of the building, culminating in a spectacular reading room with panoramic views on the top floor. Since its opening in 2004, the library has become a favorite hang-out place for youths and homeless – it has about 8,000 visitors each day. (Photo: Philippe Ruault)

-

Seattle’s public library by OMA − in collaboration with LMN, 2004 − has become an icon for public education. (Photo: Philippe Ruault)

-

The Architect as Agent

In the context of the city in metamorphosis and a culture industry that is increasingly alienated from its own roots, the Culture:City exhibition that I’ve curated at the Akademie der Künste in Berlin explores the potential provided by selected architectural interventions with cultural intent from the last thirty years. It describes the dilemma of architects and clients building for a community of consumers who participate, at best, in a critical role. Challenged to provide an appropriate spatial and architectural setting to express what people might consider to be the essence of contemporary culture, they need to invent formats for content yet to be found – risks and issues in design that the exhibition explores. Projects from recent years seem to oscillate between market-oriented gestures and a desire for authenticity, between attempts at developing inherited traditions or doing justice to new situations. By obvious virtue of their longevity, buildings can significantly strengthen the presence and continuity of culture, but in the race for the fleeting attention of the internet generation, the architectural profession has also allowed itself to be tempted into ever-increasing extravagance. The overview provided by the exhibition highlights the difficulties involved in building effective social spaces. As the community seems to have lost the impetus to adopt its role as a client, architects become its involuntary agents – a role that seems to overwhelm them in many cases.

Before the Guggenheim Bilbao, one of the world’s main reference points for large-scale cultural buildings in a historic city was the Centre Georges Pompidou (Paris 1977) by Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers – though it didn’t drastically change the image of Paris. (Photo: Renzo Piano Building Workshop)

-

Matthias Sauerbruch studied at the Hochschule der Künste Berlin and the Architectural Association in London. In 1989, together with Louisa Hutton, he founded the firm Sauerbruch Hutton in London, and since 1993 the main office has been based in Berlin. Beyond his work as an architect, he has taught at the AA and been professor at the TU Berlin and the Stuttgart Akademie der Bildenden Künste. From 2006 he has been a visiting critic at the Harvard Graduate School of Design and since 2012 a visiting professor at the Universität der Künste Berlin. He is a founding member of the German Sustainable Building Council, a commissioner of the Zurich Building Council, a trustee of the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation, a member of the Berlin Akademie der Künste, and an Honorary Fellow of the American Institute of Architects.

Culture:City (Kultur:Stadt)

15 March - 26 May 2013

Tue-Sun 11am to 7pm

Akademie der Künste

Hanseatenweg 10

10557 Berlin

On the other hand, across a wider perpective, judicious interventions, large and small, can be shown to create a new self-awareness, helping moments of new urbanity to develop in unexpected ways.

Closing Remarks

While the projects shown in Culture:City document the rise and fall of the “Bilbao effect”, its main focus lies in those post-Bilbao strategies that strive for closer integration of cultural institutions into the social structures and creative networks of the city. These are strategies whose physical presence not only offers a landmark for effective marketing, but provides, above all, urban reservations that hold the potential for diverse cultural activities. Here culture and urban sophistication need not be manifested in the invention of ever-new experiences, but essentially in an appropriateness of how something takes place – even if it is only a banal everyday activity. In this sense cultural places can be anywhere, but they have to be created, and their inventors need intuition, empathy, courage, and endurance, as well as a certain readiness for sacrifice; because they are fighting against the inertia of habit and are under constant risk of failure. Here architects have found themselves in a strange role, serving as a kind of glue between bottom-up and top-down, working as privately funded executors of the collective interest and producing artifacts that are a tool for and an embodiment of culture, both enabler and memorializer at the same time. All this happens in the context of shrinking resources, a constantly diminishing economy of attention, and fierce competition between cities and institutions. Despite all this, the built environment, essentially the city, remains the most important manifestation of culture, and it is the tangible expression of our idea of coexistence. To maintain, protect, enrich, and refine this city is the noblest task of all of us, not just for those immediately involved in planning and building.

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Architecture starts when you carefully put two bricks together. There it begins.«

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents