-

The

Island

of

HappinessThe shadowy story of the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi

Text by Ann Lui

-

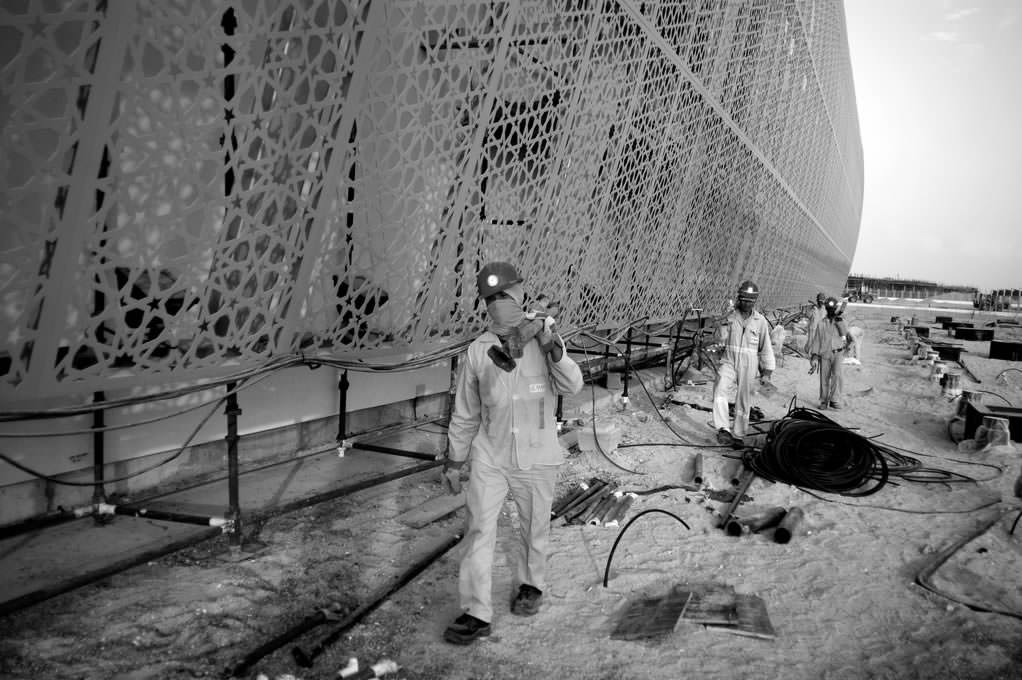

Saadiyat Island, future home of the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, has generated a contentious media storm surrounding the rights of the migrant workers. Who builds these monuments to culture? Who does “culture” exploit or exclude? (Photo: © Samer Muscati/Human Rights Watch, 2011)

-

The first thing you notice when reading PricewaterhouseCoopers’ report on labor conditions on Abu Dhabi’s Saadiyat Island are the strangely bright and cheerful photographs of workers. In one, two smiling men in blue jumpsuits saunter towards the camera against a blurry, bright white background. In another, a worker in sunglasses and striped scarf stands in the foreground against an array of other anonymous, uniformed men. These colorful images are juxtaposed against a much darker story.

Saadiyat Island’s Cultural District is the future site of the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, designed by Frank Gehry, which will accompany a crop of cultural institutions in various states of completion around the island – the Louvre Abu Dhabi (Jean Nouvel), the Zayed Cultural Museum (Foster + Partners), the Performing Arts Center (Zaha Hadid), and the Maritime Museum (Tadao Ando) – a five-for-five roster of Pritzker Prize winners. Besides these institutions, the masterplan includes an NYU campus, hotels,

PricewaterhouseCoopers was hired to write a report on Saadiyat Island's working conditions. However, images and information in the report may obfuscate the real situation on the island. (Photo: TDIC/PwC report, 2012)

-

resorts, and a marina. When construction in these firms’ own countries slowed during the recession, they were contracted for large-scale projects in a country with a seemingly more-resistant economy.

PricewaterhouseCoopers, one of the world’s “Big Four” accountancy firms, was hired by the Tourism Development and Investment Company (TDIC) to “independently” monitor worker conditions on the developer’s ongoing Saadiyat projects. TDIC, an Abu Dhabi-based firm chaired by Emirati, commissioned these annual reports in the wake of an 80-page investigation by the Human Rights Watch (HRW) in 2009. The report detailed widespread labor violations at the future sites of these high-profile institutions.

Thus far, only the retaining walls and foundation piles of the future museum have been completed - though apparently a series of Guggenheim-run programs will already begin this spring. (Photo: © BAUER Group, 2012)

»When construction in these firms’ own countries slowed during the recession, they were contracted for large-scale projects in a country with a seemingly more-resistant economy.«

-

In a 2009 report on Saadiyat Island, Human Rights Watch reported worker exploitation including the prevention of migrant laborers returning to their home countries. (Photo © Samer Muscati/Human Rights Watch, 2011)

-

An artist coaliton called GulfLabor was formed in 2010, boycotting the Guggenheim due to its alleged human rights violations against workers like these. (Photo: © Samer Muscati/Human Rights Watch, 2012)

-

»Despite an artists’ strike and ever-darkening discourse on labor conditions at the museum-in-progress, its opening date hovers on the horizon, always just a few years out of reach.«

Six years after the Guggenheim project was unveiled, despite an artists’ strike and ever-darkening discourse on labor conditions at the museum-in-progress, its opening date hovers on the horizon, always just a few years out of reach. So far, all that exists of the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi are concrete piles, Gehry Partners’ renderings, and PwC’s obfuscating report.

The original HRW report on Saadiyat, ironically billed as the “Island of Happiness,” chronicled the systematic and institutionalized abuse of construction workers — mostly migrant — on job sites. On the blind side of the pamphlets advertising “world class leisure,” the HRW reported exploitation of laborers from South Asian countries who, upon arriving at Saadiyat, found themselves “deeply indebted,

badly paid, and unable to stand up for their rights or even quit their jobs.” Following this report, in 2010 a group of 130 artists led by Walid Raad formed the coalition GulfLabor. The coalition, whose numbers have since multiplied, formed a boycott of the Guggenheim and called on the institution to take responsibility for its labor conditions – instigating a growing media stir. In May 2011, TDIC appointed PwC to provide a public annual report. Yet critics question whether this appointment is truly objective: PwC continues to do business with government-owned companies in the region and furnished its first report with an ample disclaimer that its work did not “constitute a review with generally accepted auditing standards.”

-

(Photo: © Samer Muscati/Human Rights Watch, 2011)

-

Amid continuous discourse, the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi itself is suspiciously phantomlike. Model images provided by Gehry Partners show an odd cousin of the architect’s landmark Guggenheim Bilbao. A protruding central axis is flanked by mid-rise forms of the designer’s trademark curvaceous metal panels and a seemingly random aggregate of exterior wall forms. In the fall of 2011, TDIC cut its overall yearly budget by 28 percent. The same year, bids by international contractors for the concrete works on the project were cancelled and their fees returned. Though Gehry’s multifaceted mass was scheduled to open this year, even the persistently positive director of the Guggenheim, Richard Armstrong, told The Art Newspaper: “I don’t always know everything that is going on there.” Thus far only retaining walls and foundation piles have been poured – barely the beginnings of building as immense and complex as Gehry’s proposal.

(Photo © Samer Muscati/Human Rights Watch, 2011)»Architects hold little legal responsibility for workers’ rights and safety.«

-

An artist coaliton called GulfLabor was formed in 2010, boycotting the Guggenheim due to its alleged human rights violations.

(Photo: © Samer Muscati/Human Rights Watch, 2011)

»The media fanfare surrounding starchitects like Franky Gehry creates both a responsibility and an opportunity beyond what is stated on a contract.«

-

Besides Gehry’s Guggenheim, Saadiyat Island is the site of the Louvre Abu Dhabi (Jean Nouvel), the Zayed Cultural Museum (Foster + Partners), the Performing Arts Center (Zaha Hadid), and the Maritime Museum (Tadao Ando) – not to mention endless resorts, hotels, and tourist fun. (Video and image courtesy TDIC)

-

Ann Lui is a designer and writer living in Boston, interested in the confluence of narrative and building. She studied architecture at Cornell University and has worked on projects across scales and disciplines from investigative 3D fabrication to urban high-rises. She studies the relationship between science fiction and architecture at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and is currently working at a local design firm specializing in historically-aware projects while on hiatus from school.

The heart of a museum, its art collection, is also notably missing here. The Guggenheim has promised a contemporary and regionally-focused collection of artworks, while treading lightly around discussion of censorship with its sponsors. Yet many highly-billed artists it would ostensibly include are participating in the boycott. During six years of postponements, the UAE’s local art scene has grown in its own right, including the Sharjah Biennal and Art Dubai (both approaching at the end of this March) and a burgeoning gallery network. The Qatari royal family has invested one billion pounds in contemporary art in the past seven years, according to the Guardian. Today, gallerists in Dubai say that they “don’t need” the Guggenheim, perhaps doubtful whether the western institution’s name recognition can offset the likely struggle to curate a comprehensive and critical collection. As of March 17, 2013, a list of participating artists in a new “Public Program” was released. It looks like programming will forge ahead with or without a building.

Architects hold little legal responsibility for workers’ rights and safety; after contract documents are completed, contractors take the reins. However, the media fanfare surrounding starchitects like Franky Gehry creates both a responsibility and an opportunity beyond what is stated on a contract. In other Saadiyat Island projects, such as the Beach Residences, TDIC is aiming for LEED certification. LEED, which has institutionalized metrics for the ever-nebulous goal of sustainability, includes provisions for building occupant comfort, yet barely mentions worker safety. Across the board, green projects have been no worse — but no better than — traditional projects in terms of worker safety. LEED certification through positive reinforcement has raised standards on occupant comfort alongside its more quantifiable measures. Yet the (lack of) “sustainability” of forced labor by migrant workers remains to be folded into the accreditation process.

Plans for the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi show a proposed 30,000 square feet of gallery and support space. Yet assessment of both the edifice and its art collection has been obscured by the discourse surrounding its unfinished construction. Whereas other architectural projects may be discussed in terms of their formal qualities or experiential effects, the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi is formed by reports, documents, petitions and letters. When the dust clears, and this whirlwind of documents settles, beneath it we find not a building but the exploitation of thousands of migrant workers.

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Architecture starts when you carefully put two bricks together. There it begins.«

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents