»To cut the art out and use it in new buildings is impossible« – Odd Tandberg, artist

The human cost of the 2011 terrorist attacks in Oslo was terrible, but the several government buildings badly damaged in the initial bombing, have now come under the spotlight. To restore or pull down and begin again? And what to do with the art that is an integral part of the buildings, including five murals by Picasso and work by a number of key Norwegian artists including Odd Tandberg, quoted above. Einar Bjarki Malmquist reports on a debate now raging in Norway with wide social and architectural relevance.

On 22 July, 2011, a group of government buildings in Oslo was bombed in a terrorist attack, killing eight people. The perpetrator, who was later found out to be right-wing extremist Anders Breivik, also shot down 69 residents at a youth camp on the nearby island of Utøya later that day. These events shook Norway, and Oslo city officials have faced the same dilemma that any leaders face after such a tragedy – how to deal with the site afterwards and whether the appropriate commemoration should involve restoration or destruction.

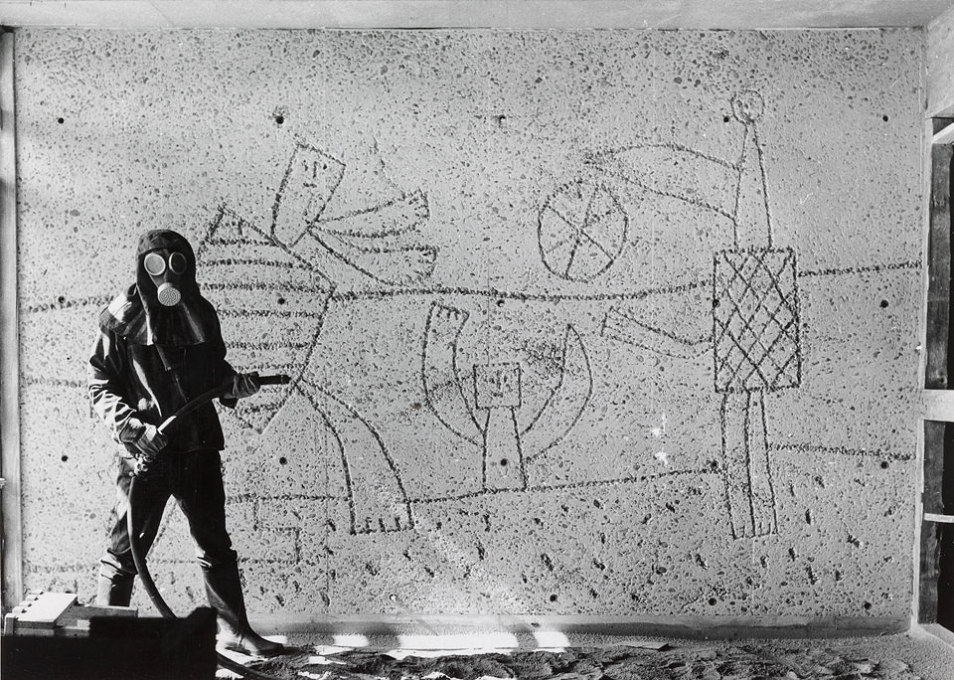

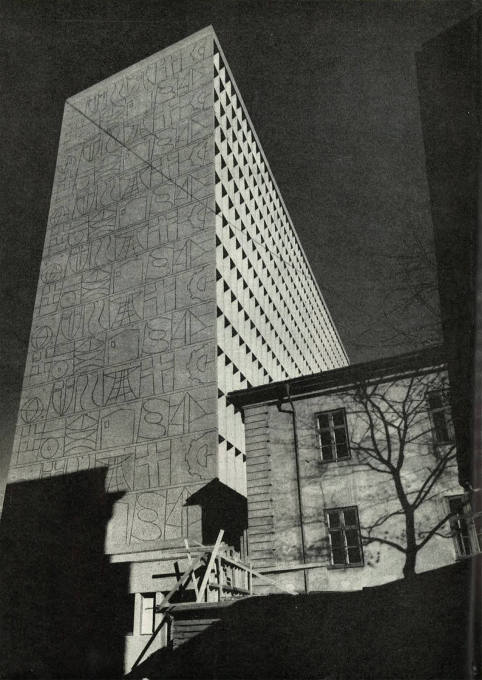

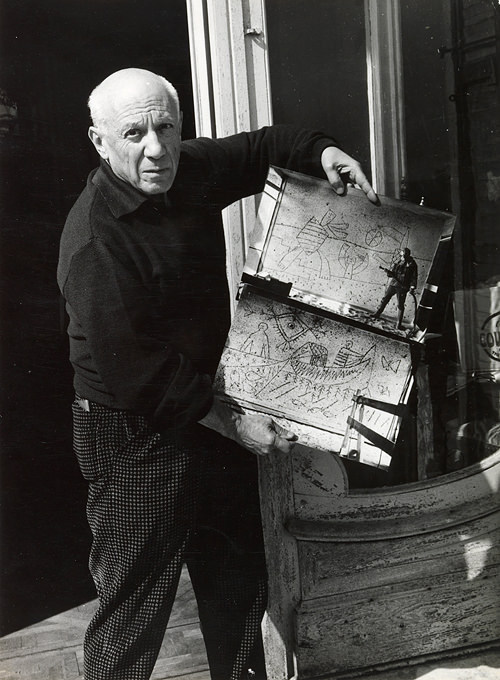

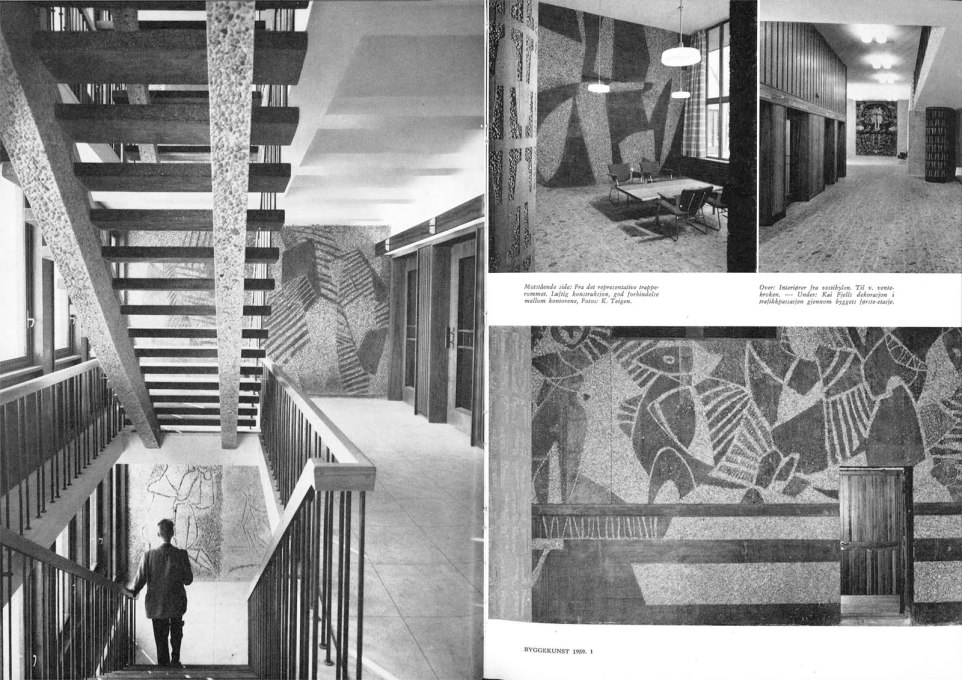

Several buildings in Oslo’s Government Quarter were heavily damaged in the attacks. These included two buildings by architect Erling Viksjø: a 1958 concrete 17-storey high-rise housing the Office of the Prime Minister and the Ministry of Justice and the Police, known as the “H-block”, and the 1967 offices for Ministry of Education and Research in a building known as the “Y-block” for its Y-shaped plan. Both buildings include artworks by Pablo Picasso, who worked with the Norwegian sculptor Carl Nesjar on reliefs for both interior and exterior surfaces, as well as works by the Norwegian artists Inger Sitter, Tore Haaland, Odd Tandberg and Kai Fjell.

These buildings and their artworks were listed for historical conservation before the attacks. After initial discussions, some of which included a proposal to build a new government quarter in a more remote place, the Norwegian government decided to redevelop the existing area. But how exactly it should be redeveloped has grown into a contentious debate that has been raging in the Norwegian media since 2011. Much of the discussion accords with conventional and conservative historicist attitudes towards architecture that canonize built work and categorically deem it to be either “good” or “bad”. This is why only two arguments for what to do with the Vikesjø buildings have arisen: either tear them down, or reconstruct them exactly as they were before the bombing.

Those on the side of destruction argue that the brutalist concrete buildings represent an ideology contrary to the ideas of the current welfare state and that their ruins should make way for more socially relevant architecture. On the other side of the fence, preservationists argue that the two buildings are significant examples of the integration of art and architecture, important reference points within the history of Norwegian architecture. Those in favour of destruction also cite the extent of physical damage (wood-framed windows and facade-elements as well as most of the interiors in the high-rise were badly damaged), but when it was confirmed that the structural supports were sound, this proved an equal reinforcement for the argument to keep the Viksjø buildings.

Journalists architects, historians and politicians alike are all taking a simplified polemic stance in the issue. Even the group of consultants who was asked by the government to develop possible future scenarios did not offer any alternative to destruction or reconstruction. They introduced five concepts: four of them include different ways to demolish the Viksjø buildings and one suggests restoring them as they were. (Restoration was not the preferred alternative; most of their arguments were financially-based and preservation was referred to as an “irresponsible use of society’s money”.) None of the suggested alternatives included a possible transformation or extension of the historical buildings.

Now, as the international press gets increasingly involved in the case as well, the specific question of what to do with the Picasso artworks inside the two buildings has come to the forefront. One of the consultants′ suggestions was to cut the artwork out of the building fabric before ripping the rest down. Opponents of this idea argue that the architecture and the art belong together, having informed each other at the time of their creation.

The magnitude of this disagreement may not come as a surprise to those familiar with debates about historical preservation. Renovation or reconstruction of historical buildings touches sensitive cultural and political nerves, bringing up questions about how a city or a nation wants to treat its own past and represent itself to outsiders. Moreover, discussions of architecture and urbanism in a broader sense are often divisive – because of their public nature, they can polarize public opinion and push those involved to take increasingly extreme opposing positions as tensions rise. This case is a striking example of the binary logic that underpins many discussions of this kind taking place all over the world.

In this case, the work of the internationally renowned Norwegian, Pritzker Prize Lauriate from 1997, architect Sverre Fehn (1924-2009) could serve as a useful precedent. In projects such as his Hedmark Museum in Hamar, and the National Museum of Art, Architecture, and Design and the Gyldendal House, both in Oslo, visitors experience an interaction with elements of history as well as contemporary materials and craftsmanship. Each of these examples of nuanced integration include transformations and extensions to existing historical buildings, creating continuity between the two and providing different spatial experiences that reflect the historical differences.

A group of government specialists has been hired to review the consultants’ proposal this autumn. Norway’s parliamentary elections will be held on September 9th and according to current polls, it looks like the specialist group will be handing their results to a new government. But the continuing pattern of polarized rhetoric dramatically reduces the opportunity for any government to use architecture to forge a vision for Oslo’s future.

Good architecture makes room for the ambiguities of life. Architecture is one way in which it is possible for multiple eras and attitudes to exist simultaneously – combining, clashing, and overlapping. Having the courage to allow for this complex coexistence, rather than insist on a straightforward reconstruction or demolition, would be the most appropriate action of all.

– Einar Bjarki Malmquist is an architect, at Malmquist Arkitektur and an editor of Arkitektur N, The Norwegian Review of Architecture, in Oslo.

For further background on the debate see the official view from the Norwegian Government on the redevelopment, opposition to the plans and architects′ support for the buildings′ preservation.