uncube’s editors took a pre-Christmas coach trip to visit a new exhibition in Bauhaus Dessau dedicated to the school’s legendary stage experiments. Elvia Wilk files the report.

In the early 1910s two housewives named Lillian Gilbreth and Christine Frederick began publishing their tried-and-tested “home-efficiency” studies, which applied Taylorist factory management strategies for maximising productivity to ladies’ housework. Their wildly popular articles, appearing in magazines like Ladies’ Home Journal, diagrammed ways to re-organise living space in order to reduce, say, the number of movements necessary to bake a strawberry shortcake from 97 to 64. The rationale being: the closer the home – and body – could come to an industrial machine, the better everyday life would be.

A promotional video for the Gilbreth Method appears on one of nine television screens stacked at the entrance to the current exhibition at the Bauhaus Dessau: Human-Space-Machine: Stage Experiments at the Bauhaus. This and other scenes of early-twentieth-century fascination with mechanisation set the stage for the show, describing a time in which technological advancement was both the enemy and the answer. World War One had barely ended when the Bauhaus school first set up shop in Weimar in 1919, and despite the recent devastating industrialised warfare, technology also offered hope for a future to fill the void left in its wake. Human-Space-Machine focuses on the resulting belief in both the machinic human and the human machine.

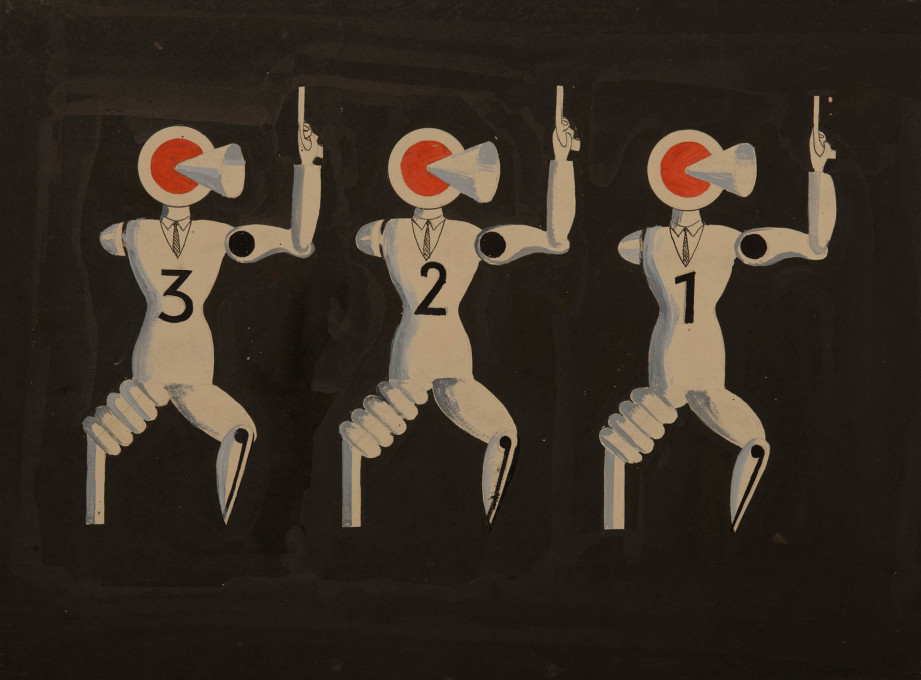

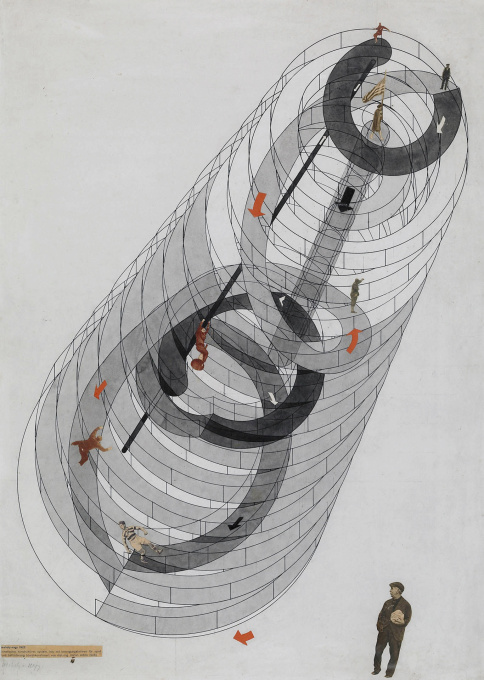

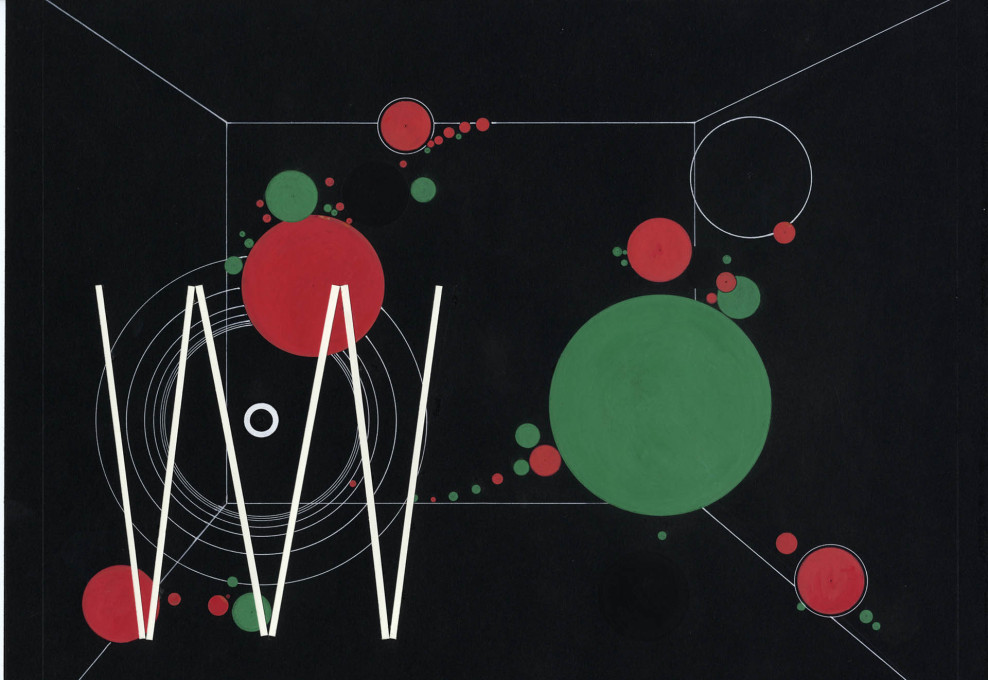

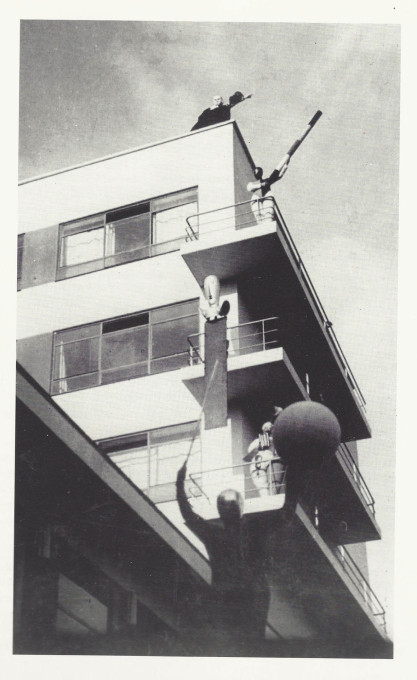

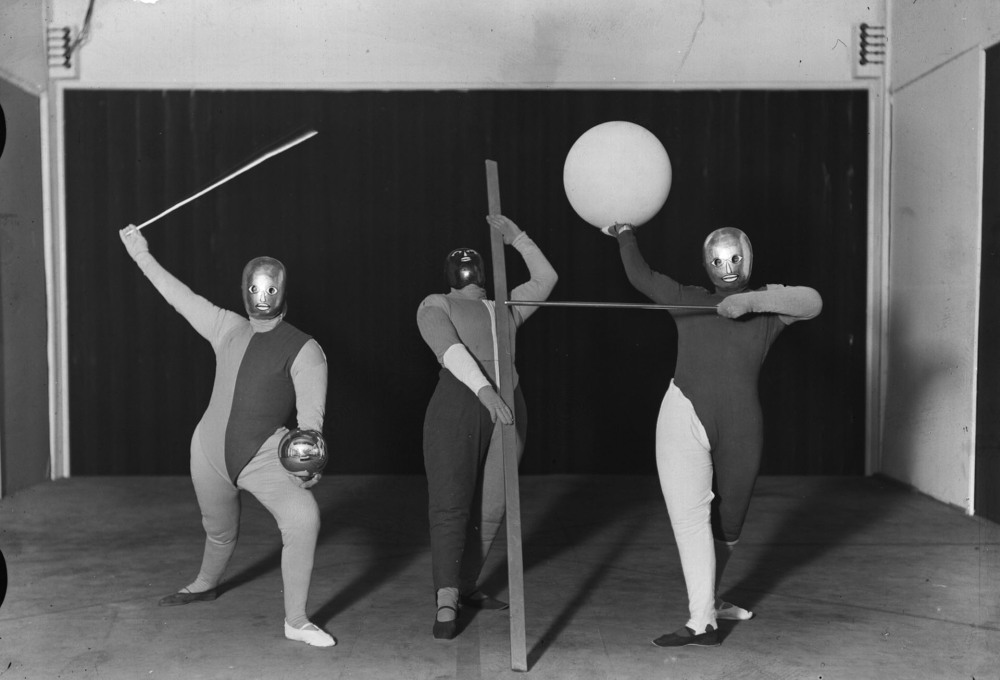

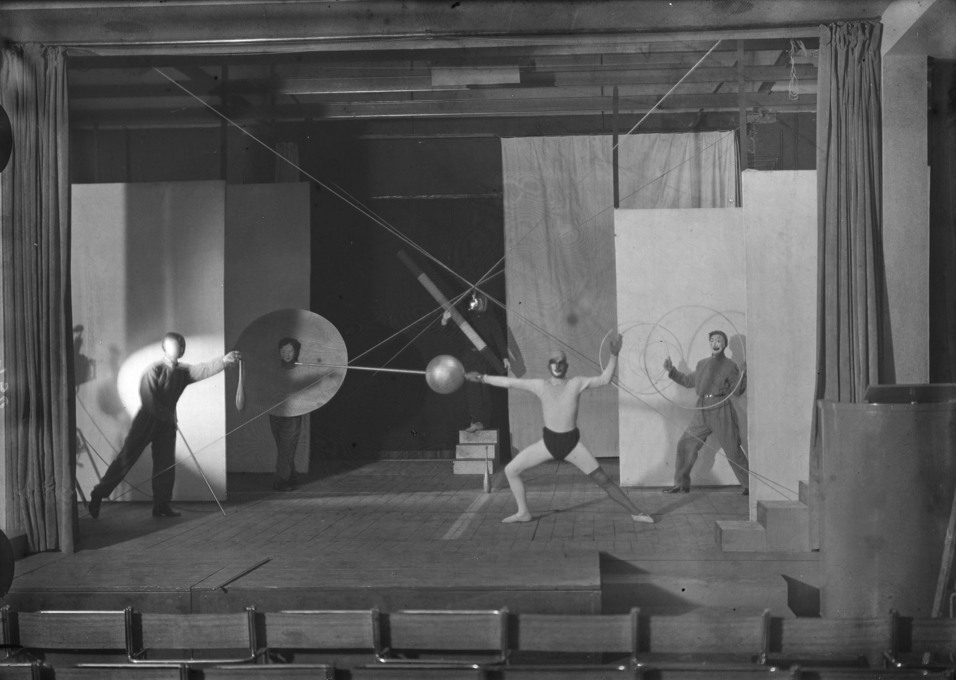

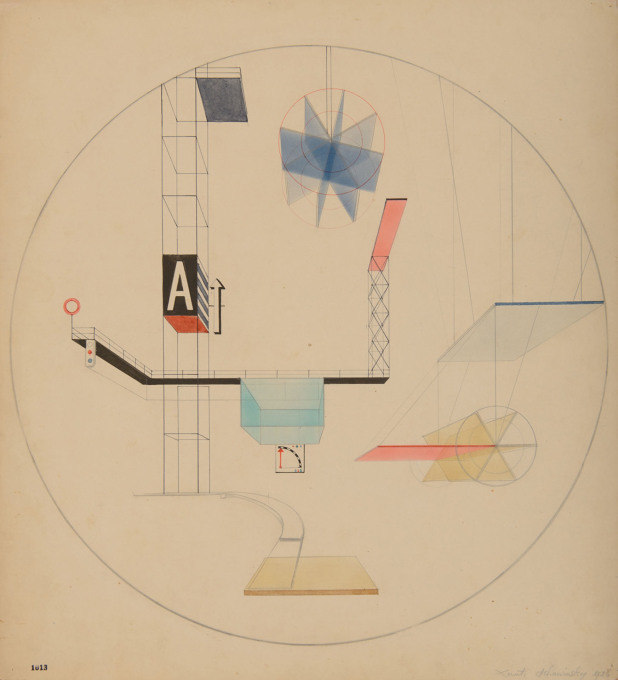

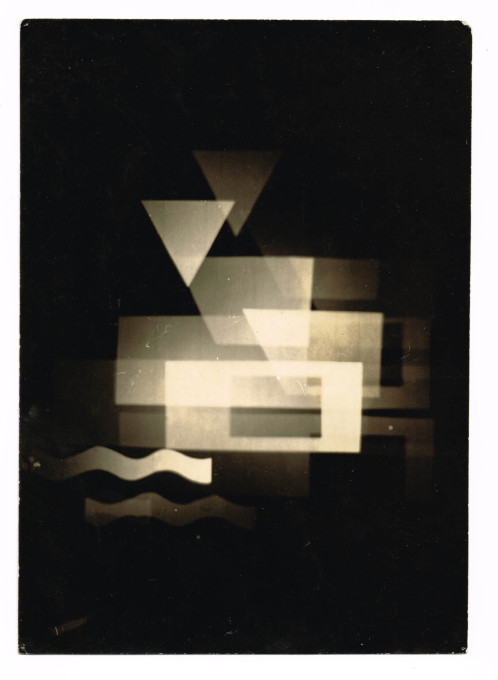

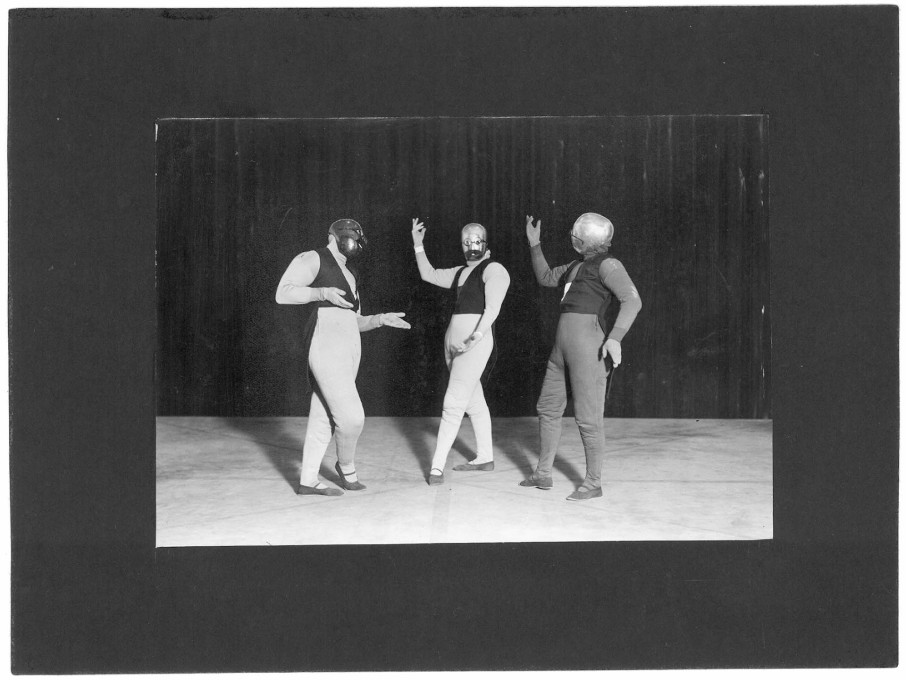

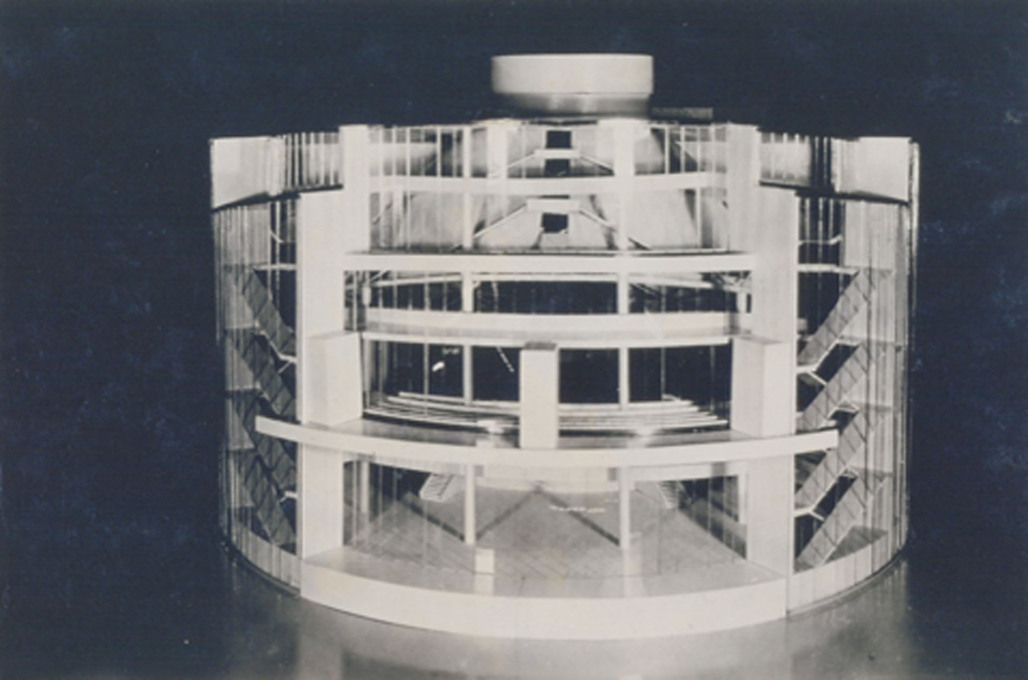

In the second room visitors can pick up headphones and listen to a “fictional trialogue” between László Moholy-Nagy, Walter Gropius, and Oskar Schlemmer discussing the theories underpinning their stage experiments. But this is just light foreplay for the real stuff in the next room. Here, a treasure trove of original material densely packs the walls and display cabinets: hand-drawings by Moholy-Nagy of unrealisable stage sets; tiny, exquisite photographs by T. Lux Feininger of actors in outrageous costumes frozen in tableaux; re-creations of Schlemmer’s Triadic Ballet projected on screens. While poring over the artefacts – familiar from hundreds of books but still stunning in the flesh – one is struck by the peculiar balance of hilarity and grave seriousness upon which the Bauhaus project hinged. The school’s earnest utopian aims often resulted in absurd attempts at machinic perfection. Moholy-Nagy once proposed a theatre play composed entirely of autonomous machines.

To see these original works in the context of the Bauhaus building in Dessau is a totalising experience: Schlemmer’s stylised, rigid, dualist representation of the human figure reflected in the symmetries of the architecture. Ironically, although the Bauhaus school exalted factory reproduction techniques, today the “aura” of the original permeates the space with a heady air of authenticity. This is why many of the exhibition’s offshoot components feel a bit dry; the disjuncture between The Real Thing In The Real Place! and the various re-enactments, speeches by historical experts, and experimental interpretations that surround this, is just too big a leap. Perhaps due to its sensitive negotiation of “real”/”re-creation,” the one highly successful adjunct is a room of re-interpreted full-size theatre costumes by students at São Paulo’s Senac University.

Exhibition analysis aside, tensions between past and present are no joke. In the days leading up to the show, Schlemmer’s grandson had a fit accusing the curators of sullying his grandfather’s name, and some of the works in the show owned by the family estate were snatched off walls during a dramatic-sounding police confrontation. What might seem a simple act of “interpreting the past” from a curatorial point of view was interpreted as defaming familial legacy – bringing up perennial questions of who has the right to access art, what “accurate presentation” is, and who should be responsible for its legacy.

Curiously, this is the first full-scale exhibition ever to focus explicitly on the Bauhaus theatre. For such a central, combinatory aspect of the Bauhaus project, why has its presentation been neglected so long? Part of the problem can probably be chalked up to institutional politics; the various Bauhaus Stiftungen have been known to be mutually competitive and even uncooperative when sharing their archival material. Who knows. But perhaps rather than asking “why not earlier?” the more interesting or prescient question might be “why now?”

The hallmark of the precarious decade of the Bauhaus school’s operation, between the world wars, was an acute feeling of acceleration towards an inevitable end. Lo and behold: this past weekend Berlin was host to the “Acceleration Symposium”, in which a roster of relatively big-name intellectuals were invited to reflect on this year’s #ACCELERATE: Manifesto for an Accelerationist Politics and its surrounding hype. If the term merits ten hours of discussion it’s best not to summarise here, but one central point the authors of the manifesto argued for is full automatisation of labour, with the goal of overturning capitalism’s wage-labour dependency. Rather than stagnate in a valley of technologically-aided production – which leaves us unemployed yet still dependent on capital, distracted by new gadgets that provide the illusion of progress, let’s charge full-tilt into the future on the wheels of full mechanization. So the argument goes.

The very same postulations about the human-machine relationship were put on stage in the Bauhaus theatre. At the risk of sounding regressive, in retrospect the Bauhaus theatre provides evidence that there are limits to how automated we want to get, at least in terms of artistic production. While it might be a useful innovation to learn how to prepare a strawberry shortcake in 45 minutes, no one really wants to see a theatre play entirely made by machines. Machine-made art is rarely more than novelty. And Human Space Machine reminds that technological utopia is likewise a novelty that is not so novel. We tried it a couple times.

We’ve been oscillating between the twin poles of technophilia and technophobia for at least a century. That’s why looking back is useful: history provides some excellent examples of both extremes. At a steady pace, technophilia leads to excellent art or weird esotericism; as it accelerates it looks more like Futurism, and at its fastest speed, well… the human-space-machine experiments were sandwiched between world wars. Acceleration is sexy – but it wouldn’t hurt to check the rearview mirror before hitting the gas.

– Elvia Wilk

Human Space Machine – Stage Experiments at the Bauhaus

6 December 2013 – 21 April 2014

Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau

Gropiusallee 38

D-06846 Dessau-Roβlau

Artistic Direction: Torsten Blume and Christian Hiller

International Co-Curators: Milena Hoegsberg, Lars Morch Finborud, Jienne Liu

Curatorial Advisor: Philipp Oswalt

In cooperation with Senac

A publication is forthcoming in January.