After more than a hundred years of planning and at the cost of almost one billion euros, Leipzig finally opened the new underground train connection between its two major train terminals. The four accompanying new stations are architecturally competent, yet uncube’s Florian Heilmeyer couldn’t help but be disappointed by the failure to include any appropriately grand gesture.

Close your eyes for a moment and think of the most world’s beautiful train stations. Most likely visions of grand halls arise, be it in Chicago, Madrid, Milan, Moscow, Istanbul, Mumbai, or − of course − New York’s Grand Central Terminal dating from 1913. Back then, when travelling by train was still an exceptional adventure cloaked in an almost religious mysticism, they built nothing less than cathedrals for public transport.

But those times are gone. There's nothing mysterious about public transport anymore. it is ruled by pragmatic, everyday routine. If this needed any architectural proof, then the German city of Leipzig just supplied it with the newly-completed City Tunnel Leipzig or, with the German affection for abbreviations, CTL.

Opened to the public in December 2013, this project has actually been in plannning for more than a hundred years. In the early part of the last century, with the industries of the surrounding region flourishing, Leipzig was one of Germany’s fastest-growing cities. In 1915 the city unveiled a major new train terminal, huge and magnificent. Situated at the northern edge of Leipzig’s historic centre, the Leipzig Hauptbahnhof was pointed towards Berlin, but had no direct connection to Leipzig’s older terminus at the southern edge of the city, the Bayrischer Bahnhof. Fuelled by the promise of technological progress and the belief that everything was possible, engineers proposed to dig a tunnel under the dense, historic centre of the city to connect the two stations. The city even approved these ambitious plans, but two world wars, five different governments and at least three economic crises have since intervened and kept the scheme from being realised. Only after Germany’s reunification were plans for the city tunnel revived.

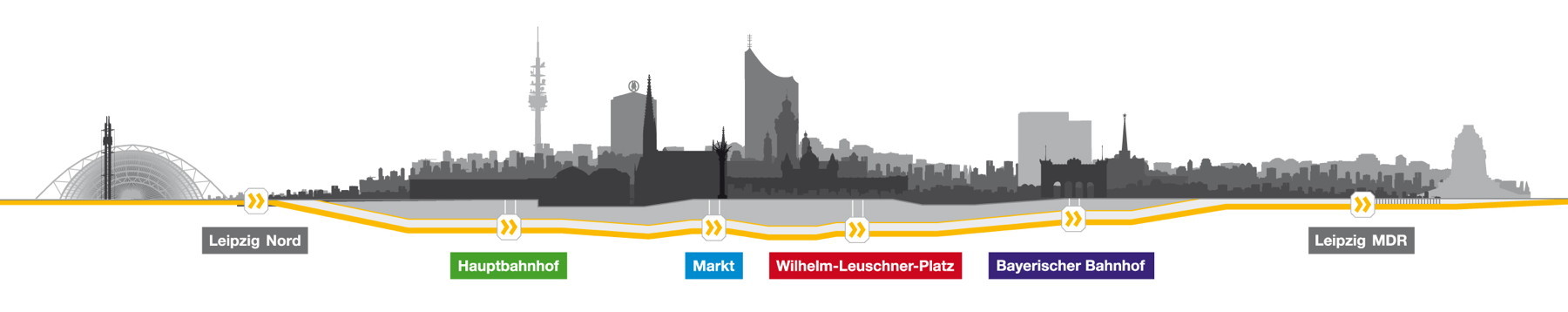

So now, over a century later, the connection is complete. A modest three kilometres long, the tunnel serves four stations: Hauptbahnhof, Markt, Wilhelm-Leuschner-Platz and Bayrischer Bahnhof, before ascending to the surface again at Leipzig MDR. Officially, the city tunnel cost a total of 960 million euros; that is a number worth writing out in full: 960,000,000 euros. Yet if you visit any of these four new stations, or pass them on a train, you’ll hardly notice that this is such a prestige project. Of course, the tunnels are shiny and new, the stations are sober and clean and at least two of them – Markt and Wilhelm-Leuschner-Platz – have an impressive and surprising height for a subterranean space. But...

The city’s ambition was clearly to do everything “right”. The four stations were designed by four different architects chosen in public competitions. Through colour, proportions and materials, every station offers a distinctive atmosphere. But what unites them is modest and rather quiet design. Obviously this architecture was meant to serve the public good in an unobtrusive way. These stations are sober spaces offering efficient solutions to passenger flows and security restrictions, they are washable, affordable, controllable public spaces, easy to maintain, resistant to graffiti and vandalism and, above all, predictable and reliable. Nothing to complain about. So why am I so disappointed?

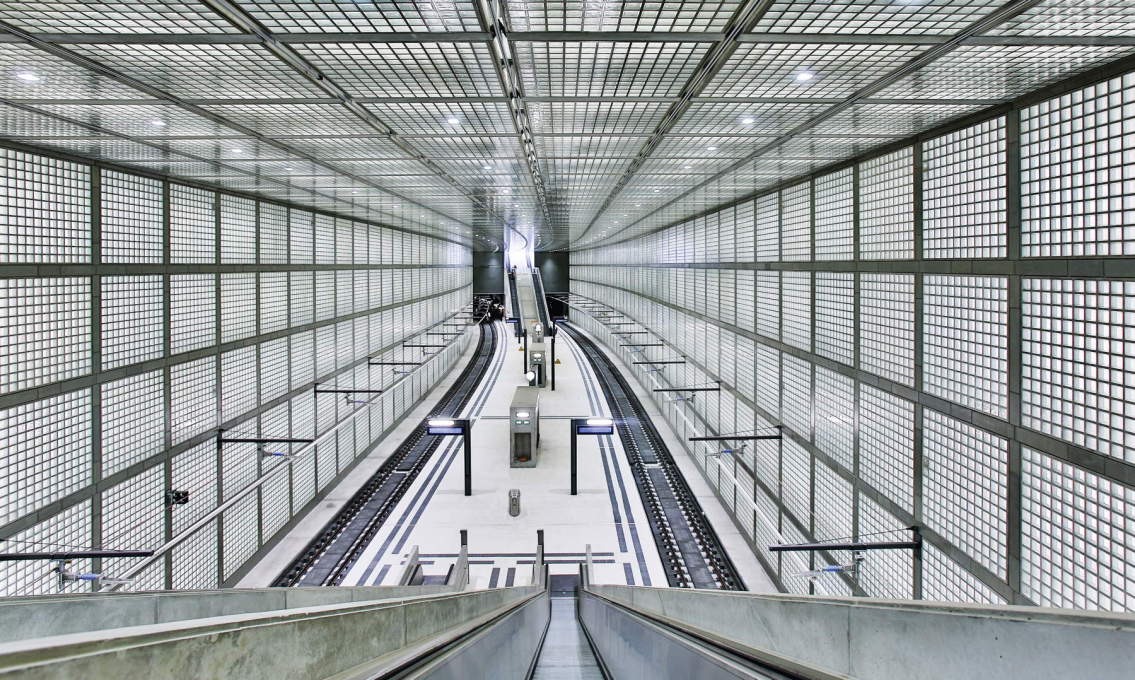

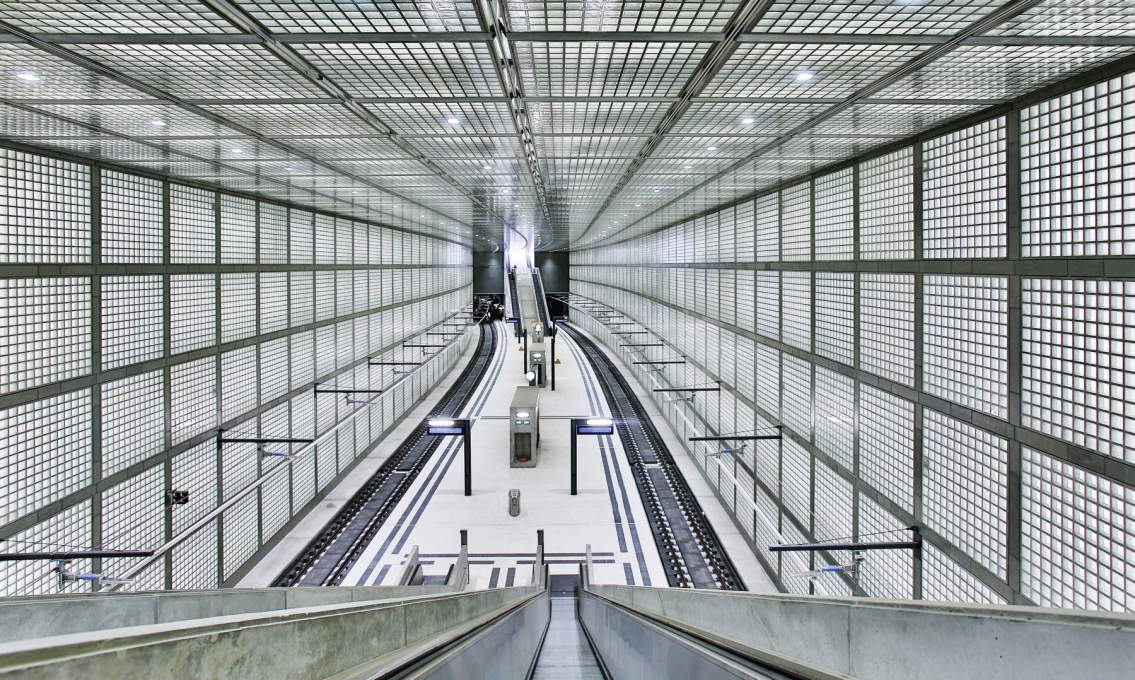

It is exactly this lack of any attempt to lend the new train line the bold expression it deserved for so many reasons. A hundred years of planning and a billion euros invested in public infrastructure have finally led to a public architecture that avoids any grand gesture whatsoever. If this really is “one of Europe’s most ambitious infrastructural projects”, as the city's PR department is so keen to trumpet, a “traffic axis of the 21st century” I think it should be. The few architectural attempts to create any type of signature seem rather helpless. The new station underneath the Hauptbahnhof creates a visible connection to the historic hall above by basically leaving its entrance as a roofless hole. Markt and Wilhelm-Leuschner-Platz stations both offer the drama of enormous height of (about 15 meters, but it feels even higher), yet both stations fail to do something with this space — neither the horizontal terracotta lamellae at Markt nor the square metal grid at Wilhelm-Leuschner-Platz give the spaces any added dynamic. Only the enormous emptiness prevents the latter station from appearing rather closely associated with cage. And if you take into account the fact that the station is subtitled Platz der Friedlichen Revolution (“Place of the Peaceful Revolution”) — the place where the demonstrations against the GDR government started in 1989 — this jailhouse grid feels even more inappropriate.

Overall this project is a perfectly pragmatic solution and of course one could be satisfied with that. Hardly a newspaper article has failed to point out that the project stayed within its given budget and time frame (more or less), comparing very favourably to other current grand projects in Germany like Hamburg’s Elbphilharmonie or the subterranean train station Stuttgart 21 (each clearly heading into the category of the Sagrada Familia as projects we may not live to see finished). But can the obvious avoidance of any grand gesture for such a prestigious public project really be labelled a better alternative? In the end, this sense of disappointment comes not from the architecture per se, but from the political intent behind the scheme, one which was obviously eager to keep the design as moderate (and modest) as possible. The architects fulfilled this assignment in a well-mannered way — but I’d prefer a touch of pizzazz. Let’s have the guts to build public buldings with a bit more glory, at least every once in a while and where it feels appropriate. If at all, Leipzig’s City Tunnel will not go down in history as anything more than example of an opportunity missed.

− Florian Heilmeyer