The patina a building gains through weathering and use is to be expected and can be a beautiful thing, but rapid deterioration in a relatively young building like that witnessed at Mauricio Rocha’s Art School in Oaxaca, which only opened in 2008, is shocking and smacks of shoddiness. Lev Bratishenko talked to Rocha about the background to the building’s present condition.

We mostly discuss buildings as if they were in a final state – finished, ruined, unbuilt, demolished – rather than in constant process. Like a photo of a soccer game, this lets temporary contingencies appear as stable constructions, which is why it is always a good idea to ask how much the architect was responsible for a building as it is experienced today.

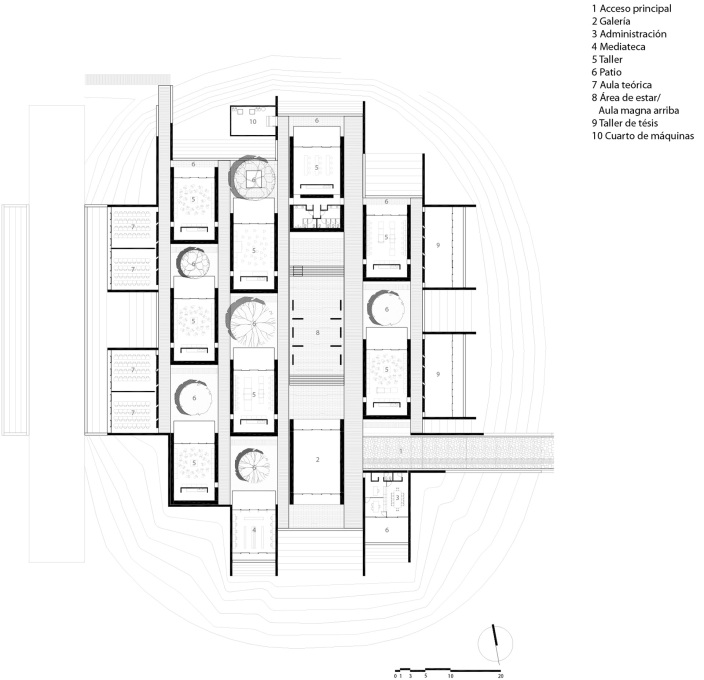

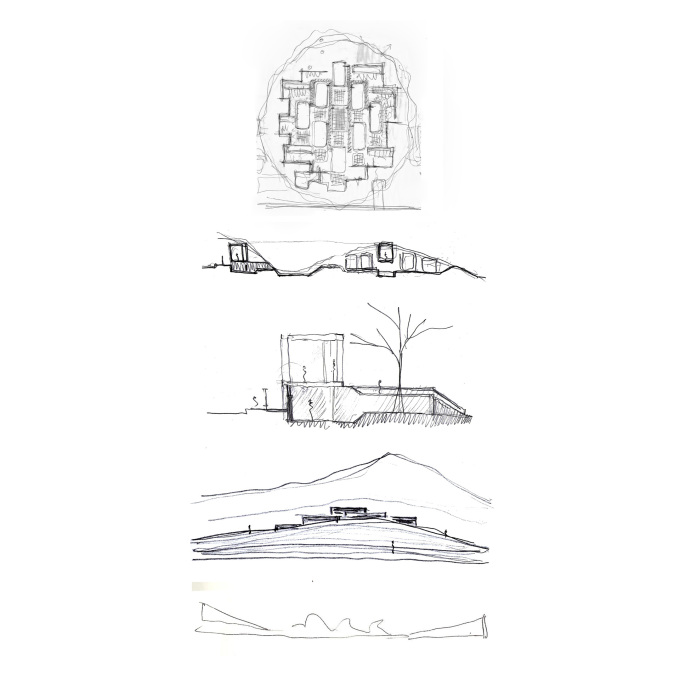

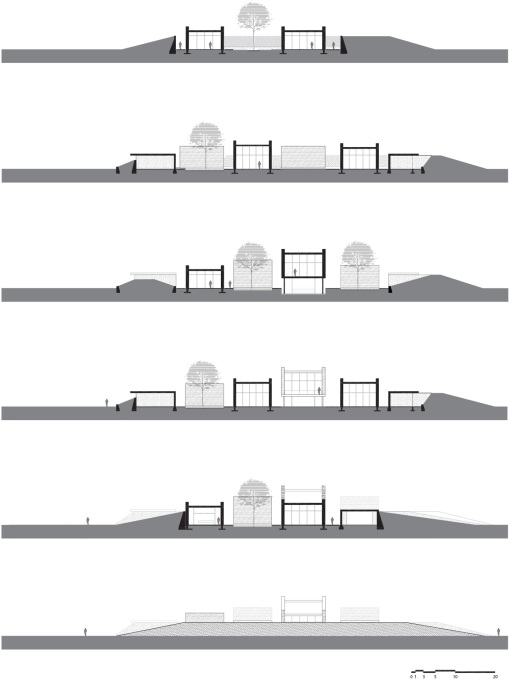

A fine case study for this is Mauricio Rocha’s School of Fine Arts for the Universidad Autónoma Benito Juárez de Oaxaca (UABJO), which opened in 2008. The remarkable design shelters a little city of studio buildings and courtyards from the rest of the campus, using an experimental rammed earth construction in a region that is seismically active, and where experience in the use of this technology was limited. When I visited the building in early 2014, I encountered signs of a difficult adolescence: shattered glass panels, thin fractures in earth walls, eroded edges, streetlights awkwardly jabbing out of walls, and a recently rebuilt central auditorium.

What happened? Depending on whom I asked, it was a design error, a drafting mistake, the contractor’s ignorance, manufacturing problems, an earthquake, a student protester, even the gardener. It is difficult to get to the truth because the construction drawings have alledgedly disappeared, but since it is the architect’s reputation that remains on the most on the line, it was logical to begin by talking to Rocha himself:

When I told people in Oaxaca that I wrote about architecture, they told me to go and see what happened to your arts school.

Mauricio Rocha: In Mexico today there are many opportunities to make architecture, but it is an unprotected process. The story of the school in Oaxaca began in 2007 when the artist Francisco Toledo asked if I would be interested to design it, but that the building had to be finished within a year.

We agreed this with the Rector of the School, Francisco Martínez Neri, but behind him there was a man named Rafael Torres Valdez, an architect and part of a group who had a monopoly on the design of university buildings. I was the first architect involved from outside this group.

That was a problem?

Torres Valdez was elected as the new Rector in 2008, and immediately told us to stop work on the building. There were some details to be finished after the inauguration, as with many buildings, but he said no. Neri paid us on his last day as he knew that if he didn’t, we would not have been paid at all.

For example, the last thing the contractor was supposed to do was inscribe a line in the rammed earth walls indicating everywhere where there were columns underneath, and they didn’t let him do this. Even when the Harp Helu Foundation wanted to give a gift to purchase vegetation and trees for the landscaping, they were not allowed.

What about the corners, the shattered windows, and the rebuilding of the auditorium building; how did that all happen?

When the school began to win prizes and appear in magazines, Torres Valdez got very mad. The corners were vulnerable because they hadn’t made the material strong enough, and he just covered them with steel profiles. I only said: please let us be involved.

In the case of the windows, the last place you can have a problem is between steel frames, concrete walls, and concrete foundations. The contractor should have left a half-centimetre gap inside the frames. This is such a given rule that you never even mark it on the drawings, but they didn’t do it. The other reason was the gardeners with their machines…

Why were the auditorium walls demolished?

The walls in the workshops are structural but in the auditorium you only have an earthen skin with concrete underneath doing the work. We found the structural engineer’s mistake when one of these two walls started leaning. Everybody said this was very dangerous, but it was only 5cm out. I visited with my engineer and we told them that there were many things that could be done to correct this.

Then, in January 2012, I was visiting friends nearby and I saw that the auditorium was being demolished. Torres Valdez wouldn’t meet with me, so I went on Twitter. And I asked the State Secretary of Culture for help, because I was doing a project for them, and they said okay, we’ll help you. So finally we all sat down. We proposed involving a third engineer for advice, but they rejected this; then we asked to rebuild the wall in rammed earth, but that my engineer would need to agree on the design beforehand.

We spent two months working on this with their engineer. Finally he agreed with the solution and the State Secretary of Culture agreed to pay 700,000 pesos towards it, but Torres Valdez refused. He wouldn’t even answer calls from the State Secretary.

Their engineer was involved in the new construction and in the end they added three columns of concrete inside the wall, and he received more fees for this further work.

Is that legal?

Well, we are in Mexico. So, finally, they built artificial non-structural walls and painted them the same colour as the rammed earth. But only on one side, because I stopped them. I didn’t make the new walls; they made them.

What’s the motivation behind all this? These struggles aren’t improving the building.

It’s not personal. It is just because I was the symbol of something threatening for this bolsa trabajo [an architectural monopoly, literally: an employment bureau]. Maybe if my building is good they will have to commission other people from outside their group of architects for the next one.

– Lev Bratishenko is a writer on architecture and music living in Montreal. This interview is part of a larger project to talk about buildings as they age. A full transcript of the two-hour conversation can be read on his website.