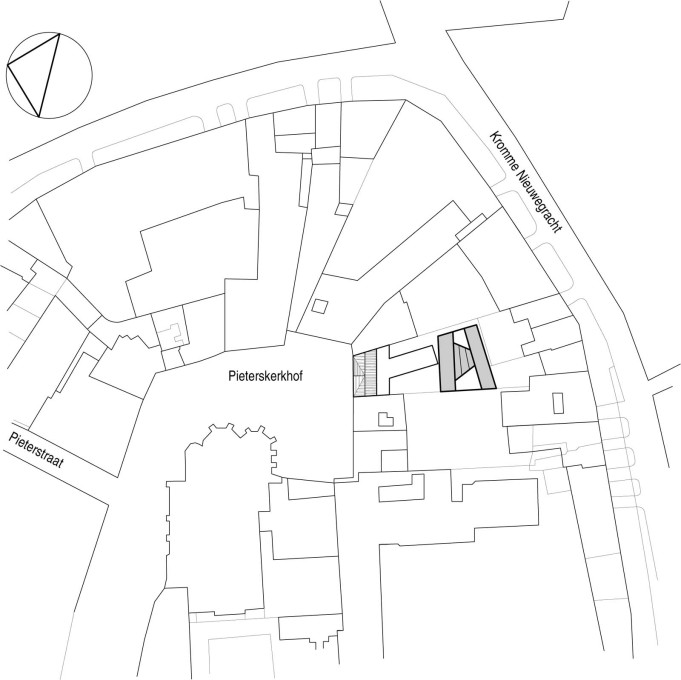

The house that Mart van Schijndel built for himself in Utrecht was designed to fit him like a beautifully tailored suit. But unlike a bespoke article of clothing, the house was not constructed to project a public presence to the world, but is hidden away from view, removed from the street. Arjen Oosterman, editor of the journal Volume, spent a day and a half there, savouring the very special atmosphere of a house that he describes as appearing initially like “the home of a suspicious hermit”.

There’s a deep cultural divide between what is shown in interior design magazines and what is shown in architectural journals. The former aim primarily at taste and comfort, while the latter centre around the purity of the architecture. However different, in both it is the image that is primary. The reader, in both cases essentially a viewer, is presented with a highly selective edit of what matters in architecture and design. Barring all other considerations, a project must be photogenic to appear in print or online. And traces of daily life are invariably missing in those photos. Ideally, the images used date prior to the resident or occupier moving in, so that the work of the architect or designer can be displayed unsullied.

The dominance of imagery makes it easy to forget that these are spaces designed for use. The notion of architecture implies that it is more than just about taste and comfort, that order, meaning, expression and other qualities are also present. These qualities are sometimes discussed in a publication’s accompanying text, but on the whole the sense of use is almost always absent.

Now it must be said that it isn’t easy to get an insight into the actuality of use. One exception to this rule is the movie Koolhaas Houselife, directed by Ila Bêka & Louise Lemoine, about the OMA/Rem Koolhaas-designed villa near Bordeaux. In it the filmmakers follow the cleaning lady on her daily trek through the house and thereby penetratingly reveal what is fantastic, but also what is problematic, about the design. Above all, it gives an insight into how architecture and life meet each other. But as I said, it is unique – if only because virtually no critic gets the opportunity to spend more than a few hours in a house.

With the Van Schijndel House, the opportunity arose to do just that. I was given the key and unhindered access for a day and a half. It was a rare opportunity to experience how a house “behaves itself” when used, and find out whether this bespoke suit of Mart van Schijndel’s would comfortably fit someone else. It makes a difference whether you come to drink tea with the owner, or get to make your own.

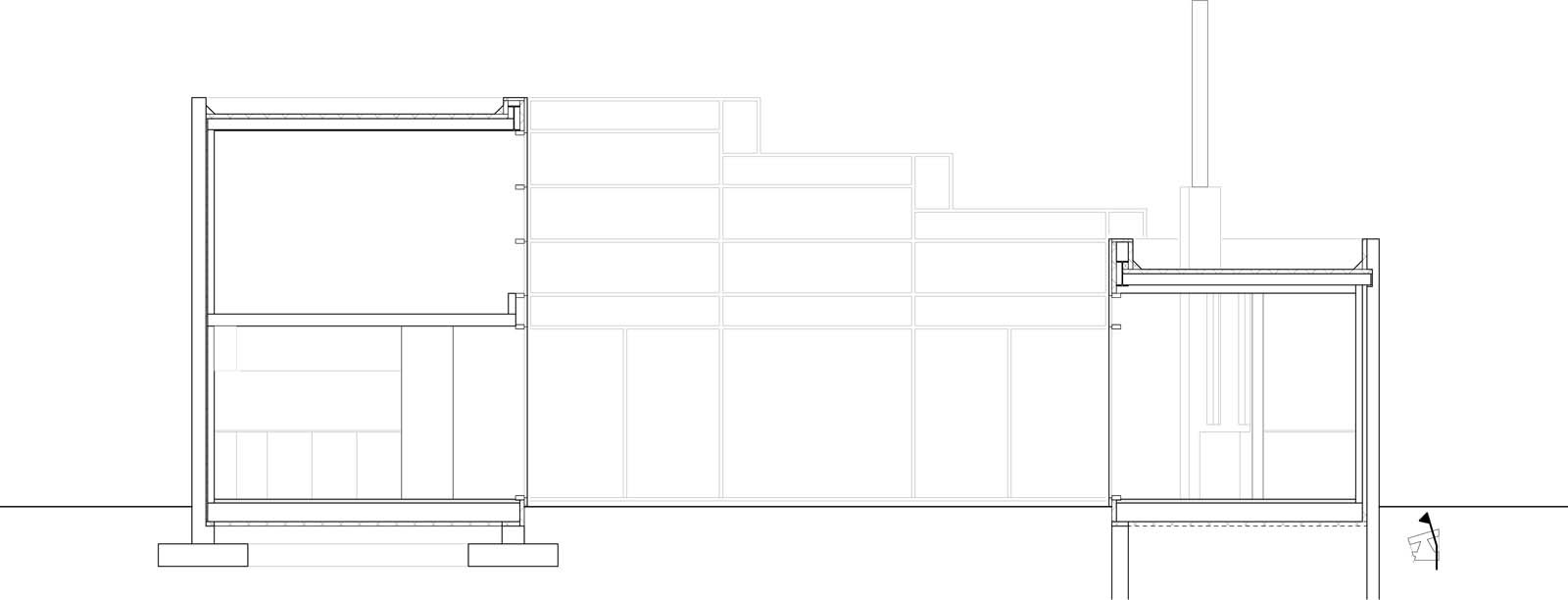

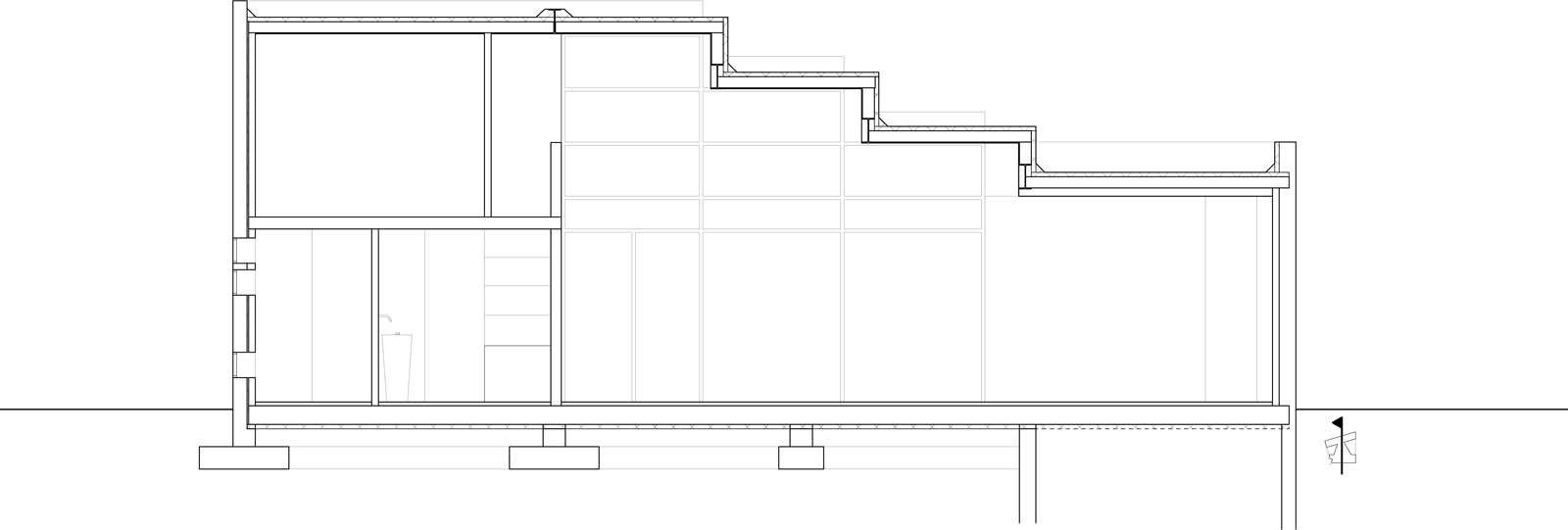

Physically, it appears to be the home of a suspicious hermit: the house dissociates itself from the street, tucked away behind a row of townhouses, with its inner domestic sphere then hidden behind a second barrier: the virtually windowless wall that forms its façade. The only indications of inhabitation are a dozen spy-holes in the paranoid front door – no welcoming gesture, although the walk up to the entrance, under the arch of the porch and past a ground floor apartment, has an intimate, villagey “Good morning, neighbour” sort of character. But beyond the front door another world opens up: lightness and transparency permeate the house itself.

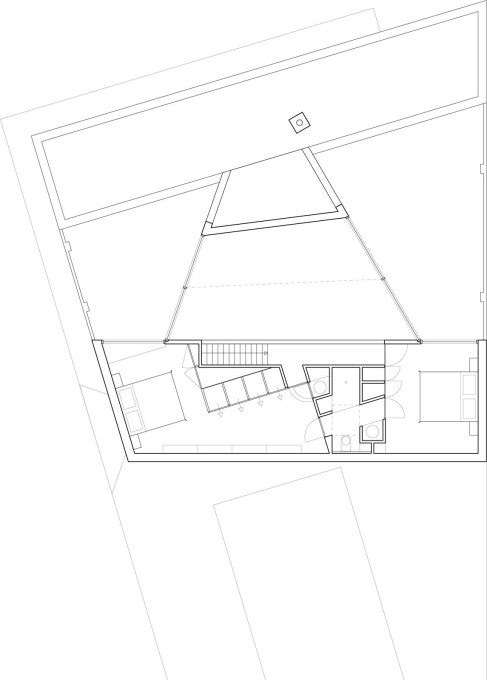

Past the secretive enclosure, what prevails inside is living with sunlight, which, like a clock, makes the passing of the day concrete. Yet however separated from the bustle of the street, the house is right in the middle of Utrecht. The domestic sounds from surrounding houses and the bells of the churches in the neighbourhood break the silence pervading the home. This mix has a relativising effect. Indeed relativity is, in many ways, a characteristic of the house.

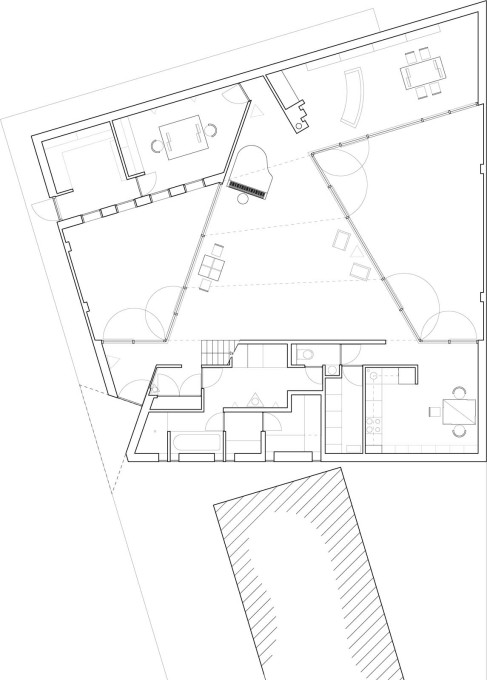

No buildings overlook the house, yet one is aware of the proximity to the neighbours. The house is generous for two people, but seems less suitable for a family. There is a very wide range of bathing options – different showers, a bath, solarium and sauna (there was even an unrealised plunge pool planned for outside that would have been directly accessible from the bathroom) – but all executed on so compact a scale that this produces no exaggerated sense of luxury. The property is hedonistic and austere at the same time. No sensor-controlled lighting or integrated information and music systems, no walk-in closets either. Basic kitchen equipment, underfloor heating, a limited palette of materials.

It is relativity that is expressed by the details, too. The glass walls become costly elements in the house, thanks to their complicated, open-folding patio doors, but in their basic detailing they are neither abstract nor untouchable. And that’s really the experience throughout the house. It invites you to use it and does not force you to take special care. Coffee in the kitchen, on the patio outside, or maybe just in front of the television? In that respect, the house is generous, providing opportunities and allowing choices. Including that of isolating yourself in one of the sleep/study rooms upstairs or in the workshop at the back.

However, the house is not resistance-free to every application and user. A peculiarity of the ground floor is that it “cleans itself up”. Clutter has no chance thanks to the virtual absence of walls and corners. And the central area seems deliberately obdurate. As neutral as it looks, it is very difficult to know how to occupy it, at least in the short term. To develop a natural relationship with it would require prolonged use.

Such a relationship is instant with the kitchen, however. Although not a real family kitchen, it is clearly the place where, as well as meals, reading the newspaper or just working on the laptop can happen. And the place also to take another look at the famous glass kitchen cabinet doors hung on silicon-adhesive hinges, an invention as surprising in its simplicity as it is elegant.

But in the house there is one detail which brings you much closer to its creator. Just around the corner from the kitchen is a toilet. Here you see that the handle of the door, which opens out against another door, has been adapted to fit into the plane of the other door, so that the latter is not damaged. It betrays an attention to detail down to the cubic centimetre which could seem somewhat forced, but which through simple craftsmanship becomes moving and precious. Precisely because this detail shows a break in perfection, a pragmatic solution to a problem that really should not have existed, the house is human and within reach.

– Arjen Oosterman is an architecture critic and curator, and the editor of the journal Volume. He is also a lecturer at the architecture academies of Amsterdam and Groningen and at Utrecht School of Arts.

The original version of this article appeared in the book:

Van Schijndel House, The House of the architect Mart van Schijndel

Natascha Drabbe, Hans van Heeswijk, Arjen Oosterman, Jane Szita

NDCC Publishers, 2014