In 1975, after visiting two of Ludwig Leo’s buildings in Berlin, the (himself unusual) architect Peter Cook penned an article about Leo entitled “A most unusual architect” in which he wrote: “The buildings are so original and so expertly achieved that in the long run they MUST be exposed, they MUST be talked about, for there is so much crap around.” In fact this never really happened: until now. For Leo and his oddly distinctive buildings were almost forgotten, only to be slowly rediscovered over the past few years. This was in part due to the exhibition Ausschnitt – or Cutting – shown in Berlin in 2013 and now – in a reworked version – coming to the Architectural Association in London, presenting five of Leo’s buildings. Here in an edited version of the introduction to the forthcoming English version of the book Ludwig Leo Ausschnitt, Jack Burnett-Stuart and Gregor Harbusch, two of the curators of the exhibition, give a flavour of the extraordinary and original buildings that this “most unusual” architect produced.

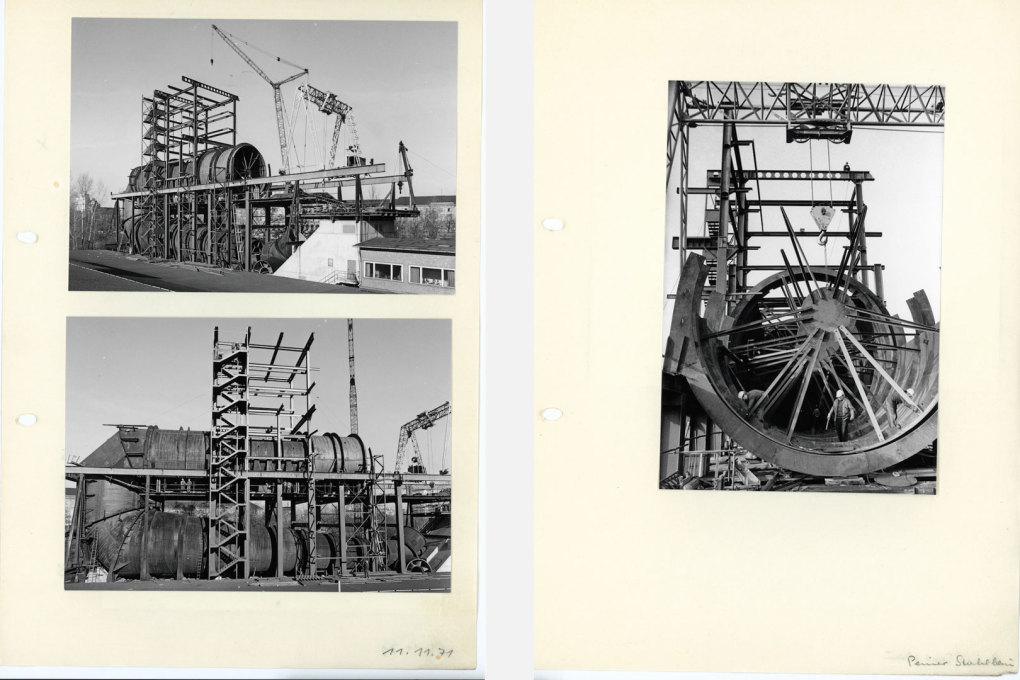

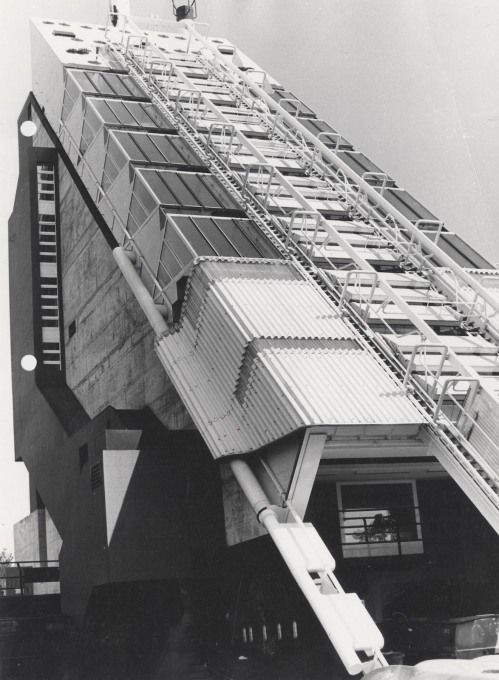

Grafted onto a small island in the Landwehr Canal, in west central Berlin, is a large building that has inscribed Ludwig Leo (1924–2012) on the collective consciousness of the city. The Umlauftank (“Circulation Tank”) – or more colloquially the Rosa Röhre (“Pink Pipe”) – is a device for experimenting with ship models, the main elements of which are a 120 metre long loop of pipe, painted bright pink and topped by a five-storey blue laboratory facility. Leo realised this spectacular building with the engineer Christian Boës between 1967 and 1974. In a few bold moves he created one of the city’s defining architectural works: a building that can be read as an assertive response by an avowed modernist to the early postmodern demand for “complexity and contradiction”. This high-tech machine, both monumental and mysterious, has simultaneously drawn attention to its architect yet distorted our perception of him and his work.

While technology fascinated Leo all his life, his work cannot be reduced to those terms. He was also never interested solely in the design of just external form, but understood architecture as a complex interplay of function and form, of spaces and user needs, of politics and history. A close examination of his work reveals an uncompromising conception of architecture, encompassing everything from the way projects were embedded in their topography and historical context, to the drawing up of 1:1 construction details. The starting point for this was always an engagement with the future users of the buildings, both as physical beings and as social actors coming together for learning, work, pleasure or living.

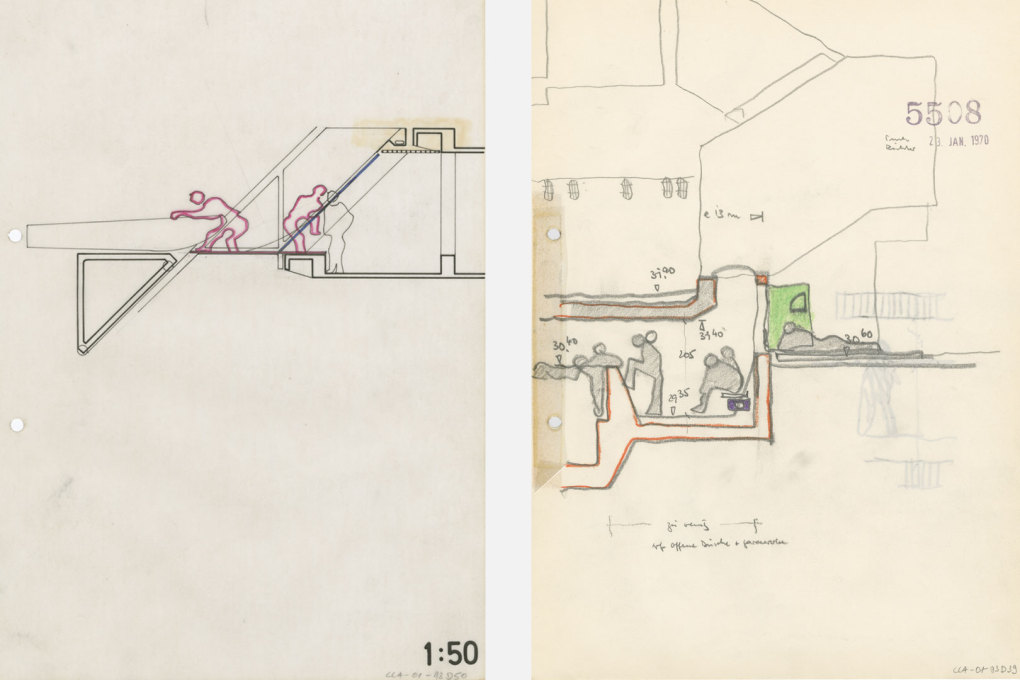

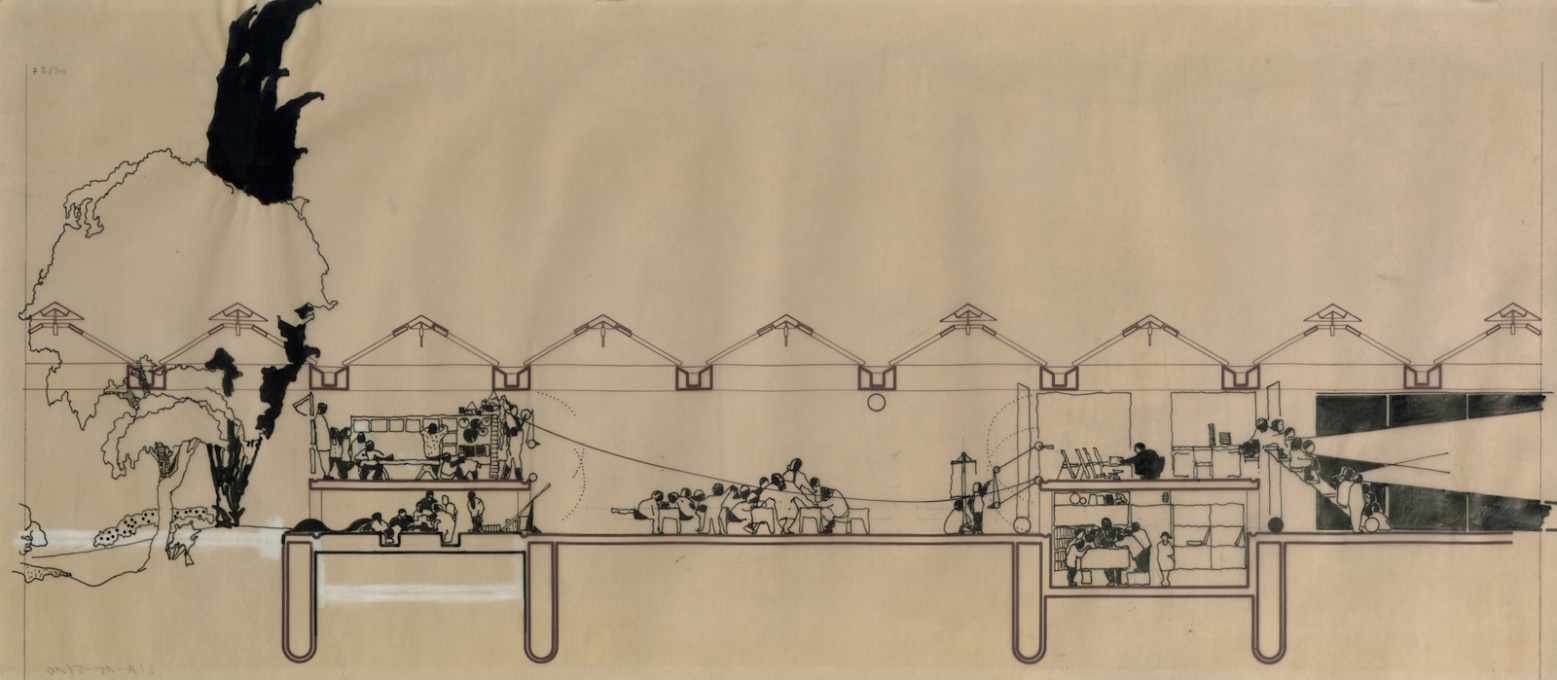

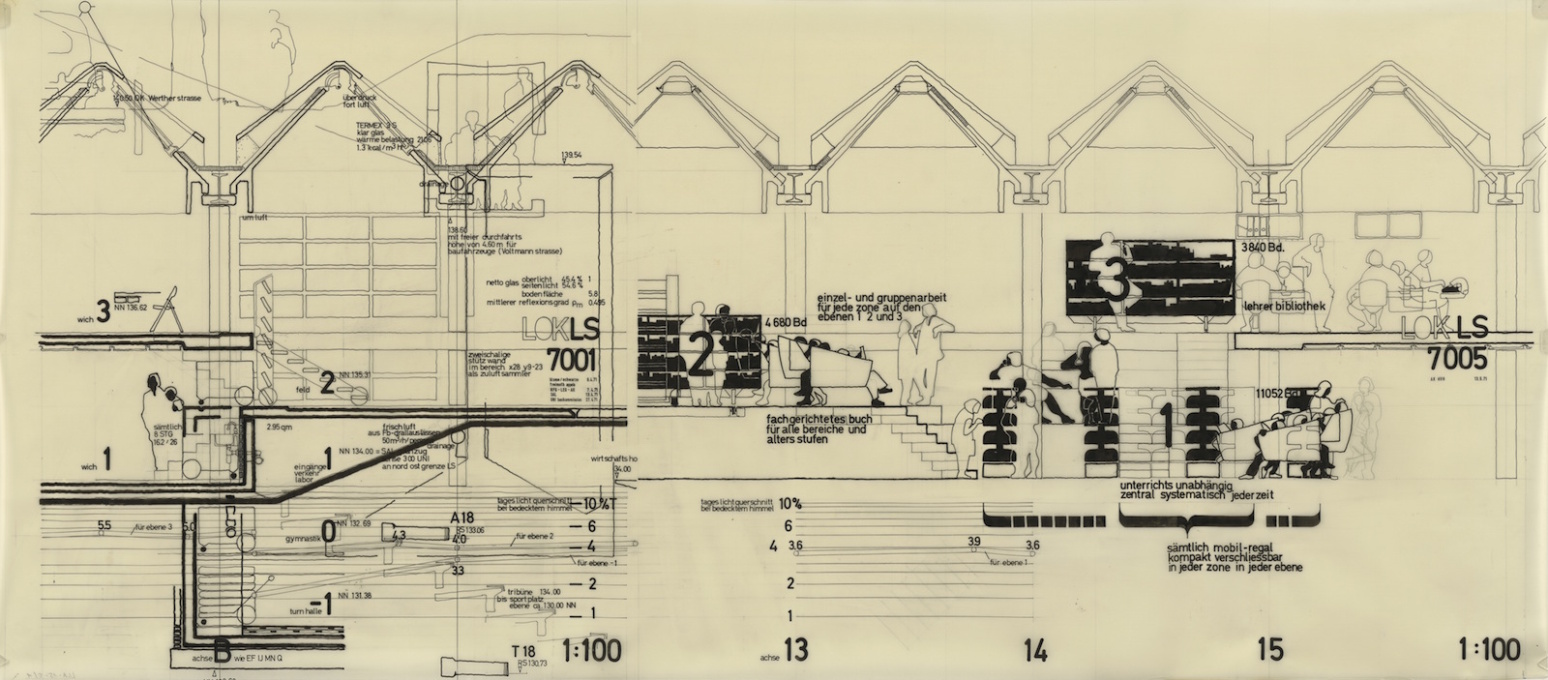

His outstanding drawings make clear the way in which he designed rooms, fittings and construction details based on a precise understanding of their use. He projected conditions of everyday use and social interaction, attempting to put himself in the place of the future occupants; to establish the dimensions and possible utilisation of his designs, he inserted figures at decisive points through the design drawings. Leo understood drawing as an instrument of architectural thinking and communication, a means of reaching an understanding with colleagues and co-workers. Consequently, a large proportion of the drawings produced by his office either came directly from his hand or bear his decisive imprint. Their quality, in terms of both their graphics and content – the system of ordering, the levels of information provided, the placing of the figures, the minimal captions, as well as what was not represented, of course – always directly reflected Leo’s way of thinking and his passionate engagement with each of his projects.

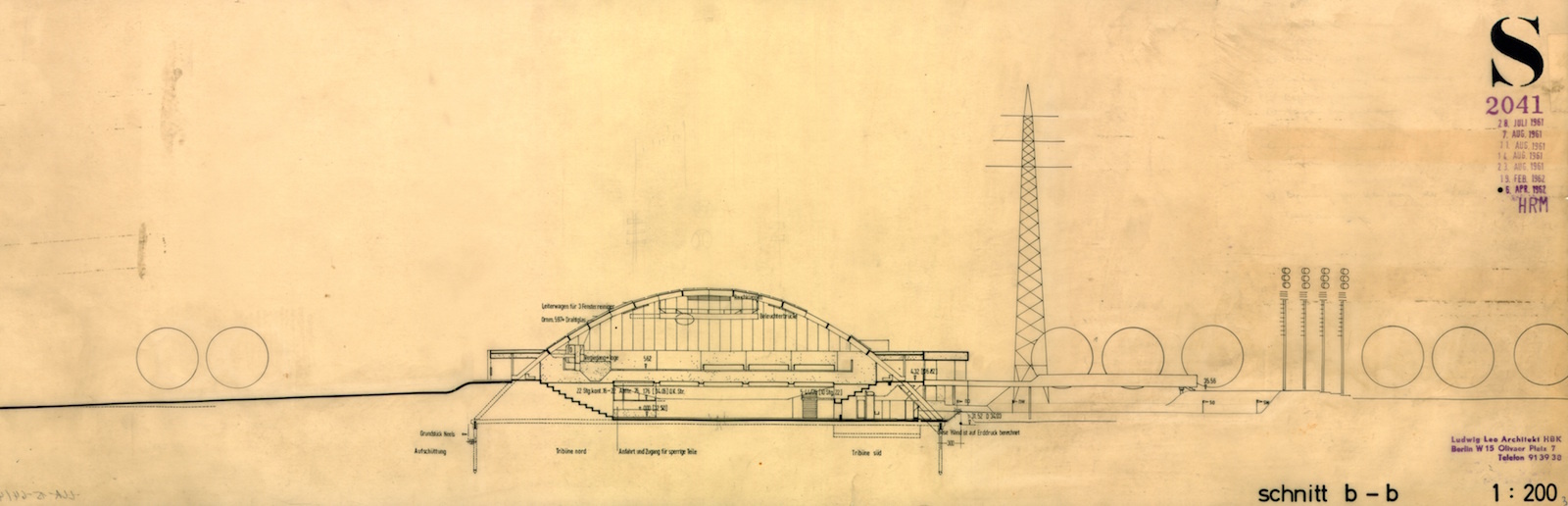

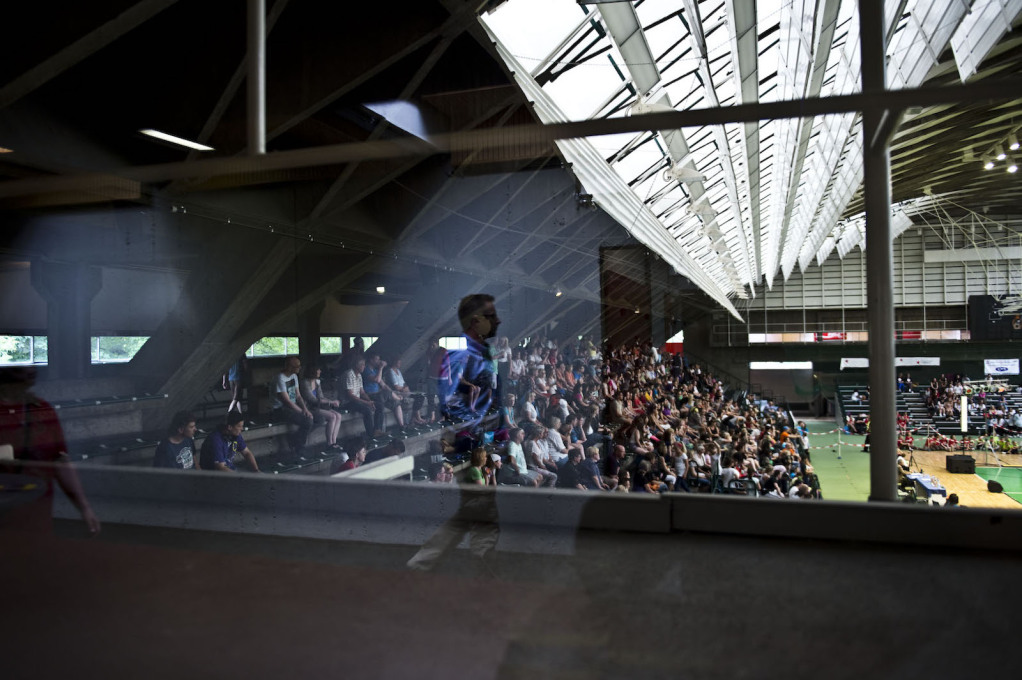

Apart from the pink and blue Umlauftank, there are two other specific buildings by Leo in Berlin that haven’t been altered substantially and can still be appreciated today. The Sporthalle Charlottenburg (1960–64) in the Sömmeringstraße near Mierendorffplatz was the first large building that Leo designed by himself, and he would later refer to it as his best work. The hall was cleverly embedded by Leo into the riverside landscape of the nearby Spree, and is impressive on account of both its meticulous detailing and its uncompromising formal language in fair-faced concrete.

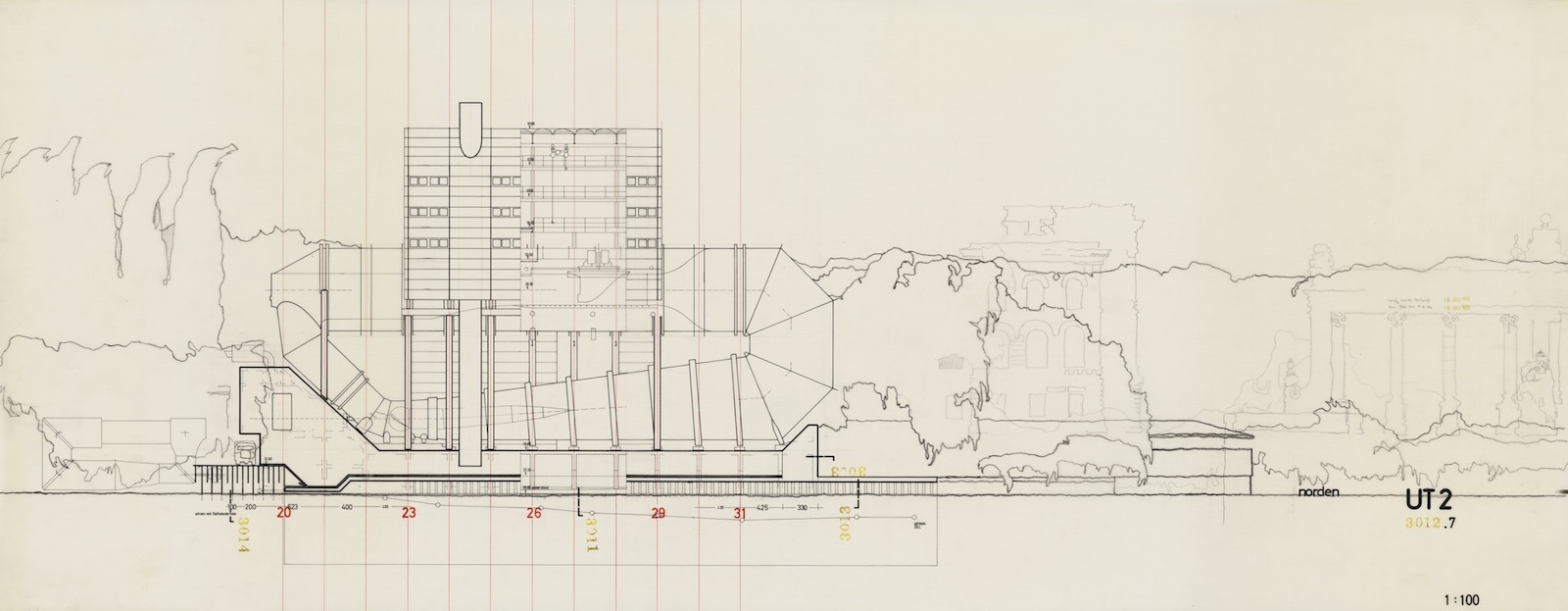

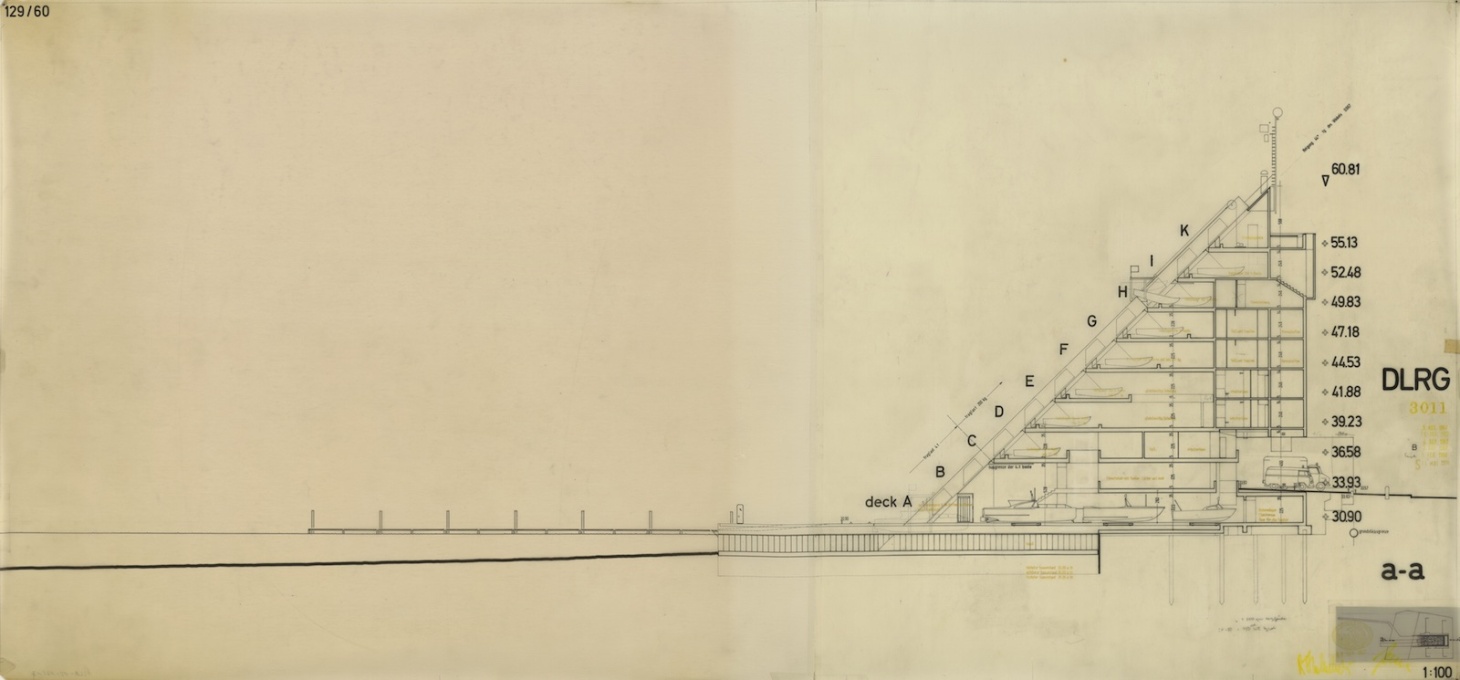

The DLRG-Zentrale (the headquarters and lifeboat store for the German Life-Saving Association), realised in 1967–73 on the Scharfe Lanke in Berlin-Spandau is Leo’s most sophisticated building. Besides the unusual triangular form, what is most intriguing here is the compact organisation of the spatial programme, where Leo took his cue from the functional characteristics of ships. The DLRG-Zentrale’s unusual brief – a sort of dormitory for lifeboats – inspired his unique interior solutions for housing them at multiple levels and the sophisticated mechanisms for winching them in and launching them, all distilled into a building that was architecturally one off a kind. And it is this very pushing of the boundaries that makes it apparent that the ideas around the projected functions and use of the building were closely intertwined in Leo’s thinking with the physicality of the building’s occupants. Yet his architecture can never be seen as a straightforward response to the needs of the users, rather a challenge – one which can on occasion seem to threaten to overwhelm them!

Two of his most significant unbuilt projects were commissioned in the context of the reform movement in education and educational facilities in Germany from the mid-1960s onwards. Along with radical teaching experiments and new ideas for integrated schools, new construction techniques were debated, drawn up and trialled in quick succession, leading to an unprecedented boom in school building. Leo’s design for the Laborschule (laboratory school) Bielefeld from 1971 is his most ambitious contribution in this regard. Designed for the educational reformer Hartmut von Hentig, the open plan school, organised around a split-level section, is lit and ventilated as naturally as possible. In addition, Leo’s study for the extension and conversion of the Landschulheim (boarding school) am Solling in Holzminden (1973–75), a progressive school founded in 1909, was also conceived within the context of educational reform. Given the task of providing new accommodation for students at a rural school, Leo devised extremely compact private living modules, triangular in section, which could be docked in long rows alongside the massive existing buildings.

Beyond the buildings themselves, it is above all Leo’s method of working – putting aside its historical contingencies – that can still inspire us today. His experimental approach to the brief, his unconditional questioning of planning conventions, his critical dissection of spatial programmes, his inventive details, his focus on people as social actors in space and his conception of the complex interrelations that make up architecture, all embody an attitude that is as relevant today as it ever was – for the question of how to realise an architecture engaged with society has not gone away.

– Gregor Harbusch is an art historian, with a strong research focus on modern architecture and urbanism. He is currently finishing his PhD about Ludwig Leo at the ETH Zurich. Jack Burnett-Stuart is a founding member of Berlin-based BARarchitekten, who have been researching Ludwig Leo for over twenty years, and in 2013 joined Gregor Harbusch to curate the exhibition “Ludwig Leo. Ausschnitt” (co-produced by the Wüstenrot Foundation which is also restoring the Umlauftank (Circulation Tank) at the moment). For more on their joint research/exhibition project and book see ludwigleoausschnitt.tumblr.com

Ludwig Leo – Auschnitt

Five Projects from 1960s West Berlin

May 1 until June 6, 2015

Architectural Association School of Architecture

36 Bedford Square

London WC1B 3ES