“At Wilkhahn, no two bricks will be placed on top of one another unless we are sure that a building is created giving equal consideration to ecological, economic, aesthetic and human aspects”

The furniture manufacturer Wilkhahn is one of those quality, family-run German companies like Braun and Thonet that seized the moment in post-war Germany to strike out on an enlightened innovative and humanitarian path – in terms of design, manufacturing methods and company philosophy. This forward-thinking attitude was not restricted to their products but to their workplaces and staff as well. In the 1980s Wilkhahn asked Frei Otto to design their new production sheds – which remain a rare example of his own architecture.

Wilkhahn was founded in 1907 by Friedrich Hahne and Christian Wilkening in Eimbeckhausen near Hanover. It started as a small firm making chairs from local beechwood like dozens of others, but by the time their respective sons Fritz Hahne and Adolf Wilkening took over the company in the 1940s, the scope had widened and they began working with designers from the Bauhaus and Deutsche Werkstätten and later the Werkbund.

By the 1950s Wilkhahn was an industry pioneer, experimenting with designers such as the legendary Herbert Hirche and Jupp Ernst, with new materials and with schemes for enabling employees to share in the company’s success. And all the while following a strict adherence to purist, functional design.

Innovative products such as the ergonomic office swivel chair and FS-Line ensured the company’s continued growth, so much so that by the 1980s they were in dire need of new production sheds.

But the usual off-the-peg boxes did not fit with the company philosophy: “At Wilkhahn, no two bricks will be placed on top of one another unless we are sure that a building is created giving equal consideration to ecological, economic, aesthetic and human aspects” said Fritz Hahne in 1984. This environmentally-aware attitude combined with the company’s dedication to innovation meant that it was an logical step for them to commission one of Germany’s most radical and humanitarian architects for the job: Frei Otto.

Otto was widely known for his lightweight structures but his concern for people in relation to the man-made environment around them was at the forefront of his public-spirited approach: to link lightweight construction with social considerations.

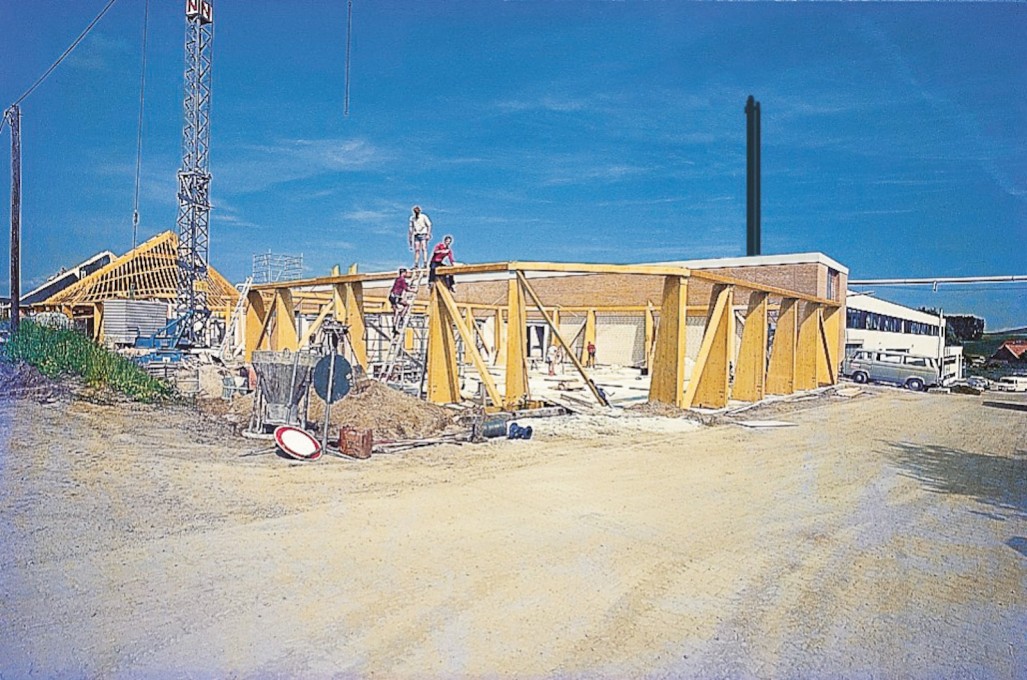

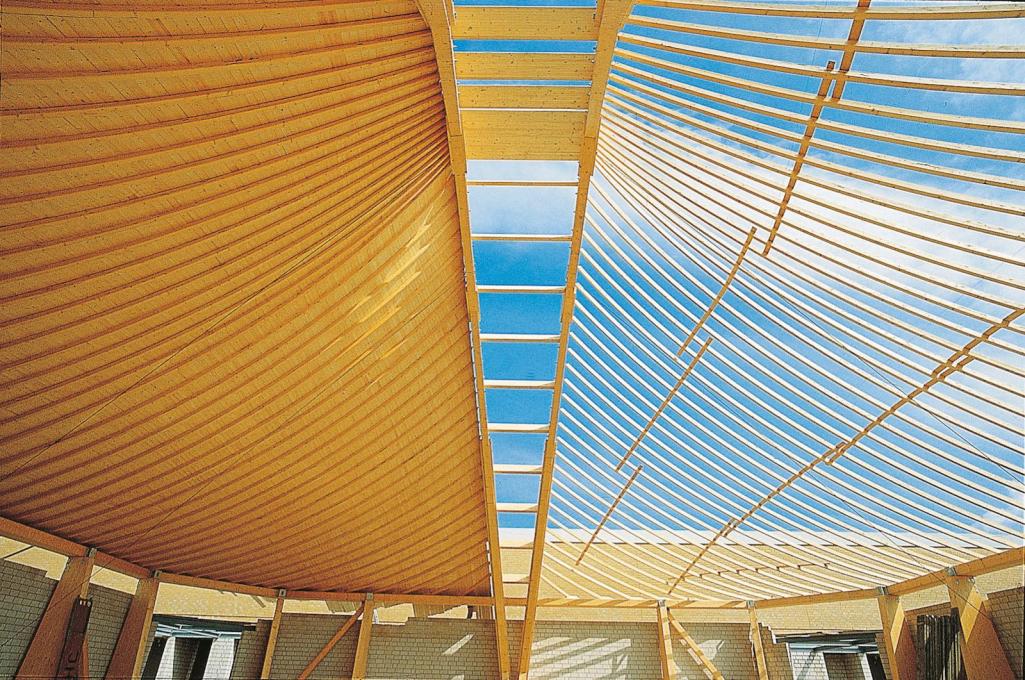

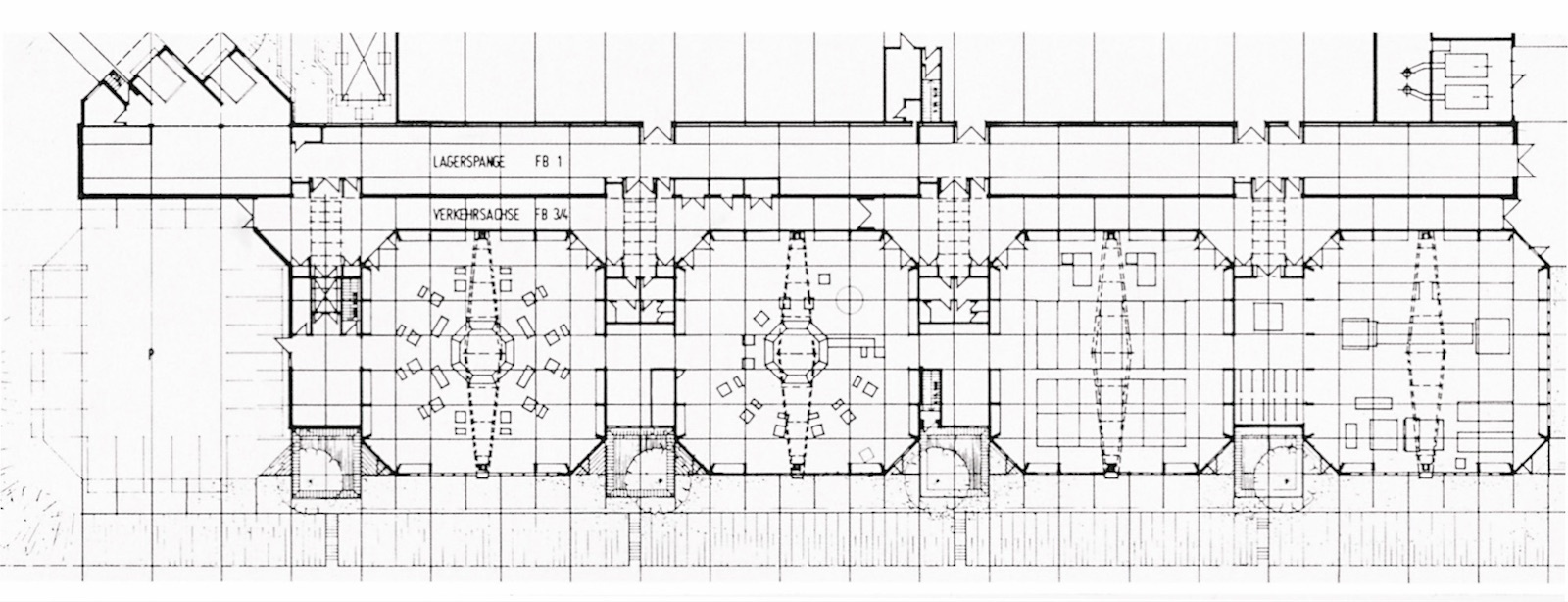

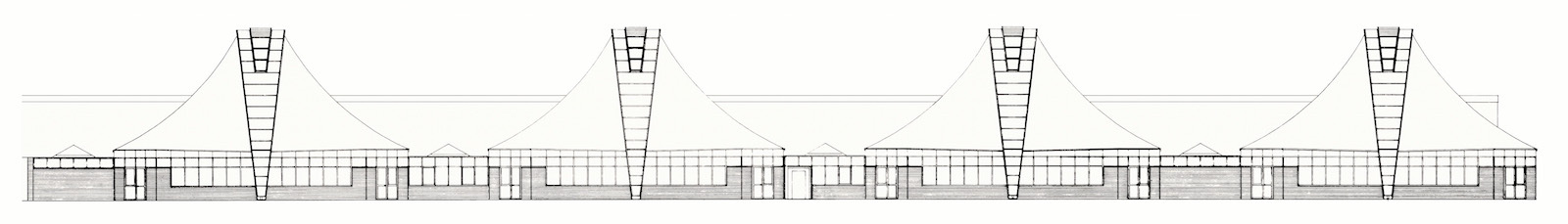

“The first talk with Frei Otto turned out to be so promising that the course for cooperation was set”, says Jochen Hahne, the current CEO of Wilkhahn, in his tribute to Frei Otto. A set of four production pavilions with a light, tent-roof construction and suspended wooden beams was completed in 1987 to house the sewing and upholstery shops. Typical for Otto, the buildings appear to be more roof than anything else from the outside, but their sweeping curved tepee-like forms sit comfortably in the landscape and the interiors are welcoming and bright; wrapping, but not dwarfing the workers within in a comforting wooden cloak. The fact that the pavilions are set in a strict row, rather than huddled in the round as one might somehow expect, probably has functional reasons but adds a pleasing sense of the modular, which echoes the nature of their purpose.

“Yet it was not only his buildings that made Frei Otto so special” continues Hahne, “It was the attention he paid to others and his respect for them. He discussed his designs with staff members, the same as he did with the management, and never hesitated to incorporate their wishes, such as for more views and bigger window areas. The same applied to the talks held at the local building authority, with whom Frei Otto, already a world-renowned architect, discussed at eye level, ‘from colleague to colleague’ in order to gain their approval for essential permits. And it applied not least to cooperating with head architect Holger Gestering from the Bremen planning group, responsible for the building on-site. For Frei Otto, cooperation was quite natural.”

Cooperation was not only natural, but a primary consideration for Otto: “Buildings are 'humane' only when they promote peaceful human co-existence”, he once said. According to Hahne, the staff feel particularly connected to these buildings and in turn they have come to represent the company and its ideals: “The pavilions have become a visible, lasting and perceptible expression of Wilkhahn's special corporate culture.”

In return, Frei Otto’s connection to Wilkhahn and the pavilions endured long after construction was completed as well. He visited and remained in contact – observing and noting how the building adapted to changing use patterns and its environment over time.

“The life work of Frei Otto was more than merely researching and building”, concludes Hahne, “for him it was about existence in itself, about decent living and working, about giving life a meaning. He went looking for models in nature, and he found them. This may be what makes his architecture so exceptional and at the same time so natural, bringing it close to us. It’s what we want for our products too. We were glad to be ‘co-designers’. It all remains alive and tangible at Wilkhahn.”

– Sophie Lovell