One of Berlin’s most important museums, the Berlinische Galerie, which focuses on modern art, photography and architecture, reopens this week after extensive refurbishment, with a spectacular new exhibition documenting 1960s Berlin. uncube is celebrating the show over the summer, with a series of articles and interviews for which the museum has granted us exclusive access to some of their extraordinary material. We kick off here – by way of introduction to the exhibition – by interviewing its curator, Ursula Müller.

What was the inspiration for “Radically Modern”? Why did the Berlinische Gallerie decide to show this selection of buildings, projects and plans from the 1960s now?

With this exhibition, we are responding to current debates revolving mainly around the appreciation of this architectural period. How is this architectural legacy perceived today and why? Was an entire generation of architects mistaken? Which buildings are nevertheless popular, even enjoying global appeal? What is the context in which they were built? The exhibition encourages a confrontation with such issues.

Why the focus on the 1960s? What makes this era so different from the 1950s or 1970s?

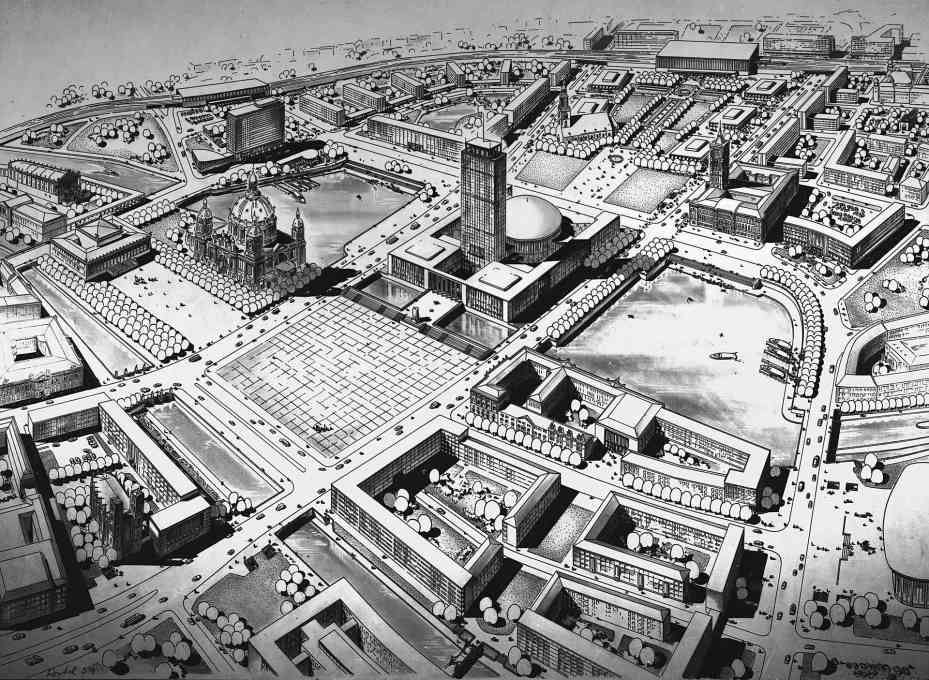

The construction of the Berlin Wall on 13 August 1961 cemented the city’s division. Urban planners had to re-evaluate their projects, which until then had been buoyed by the hope for a unified Berlin. Yet the aim in both parts of the city was to build for the whole city – Berlin became the frontline city in the Cold War. The rivalry between the political systems also occurred in the field of architecture. Despite the vast differences in their urban and architectural strategies, similar ideas were discussed in both halves of the city. In East Berlin, modern planning objectives prevailed, although they had been rejected since the end of the war as being a sign of integration into the western world. Initially, an architectural language of “national traditions” was pursued. But starting in the late 1950s in reaction to impulses from the Soviet Union, and continuing until the fall of the Berlin Wall, architectural tendencies turned in form and materiality to the functional modernism of the Weimar Republic and contemporary building abroad. In contrast to the West, the extensive nationalisation of property and land in the GDR meant that there were much larger areas available for the redevelopment of the city, which enabled a more widespread implementation of modern building concepts.

Which two projects, from the East and the West, respectively, best characterise the developments in the 1960s?

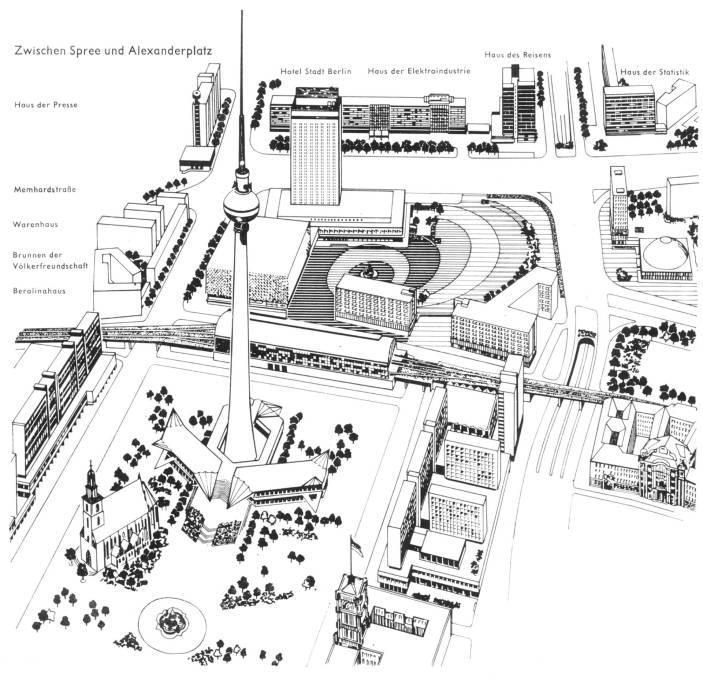

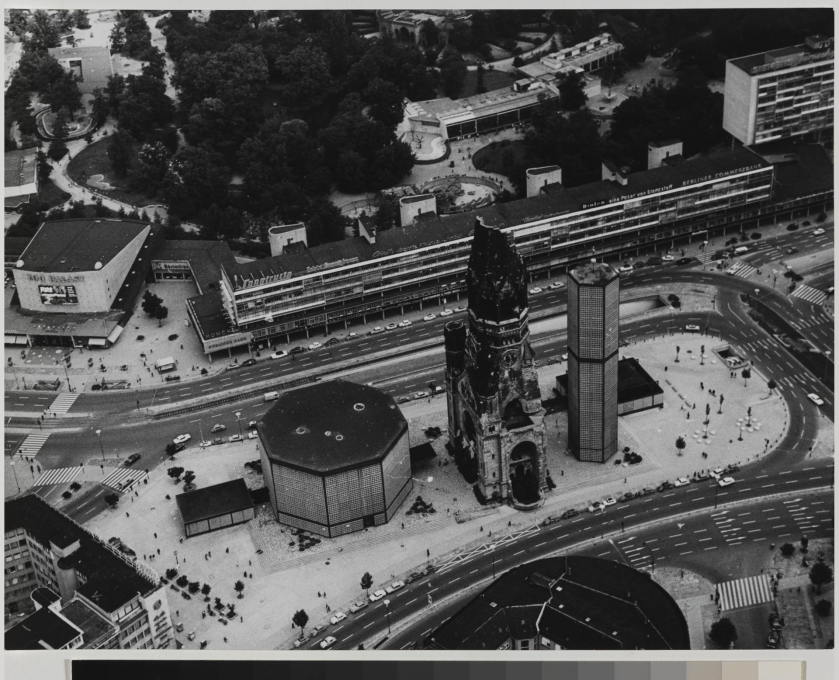

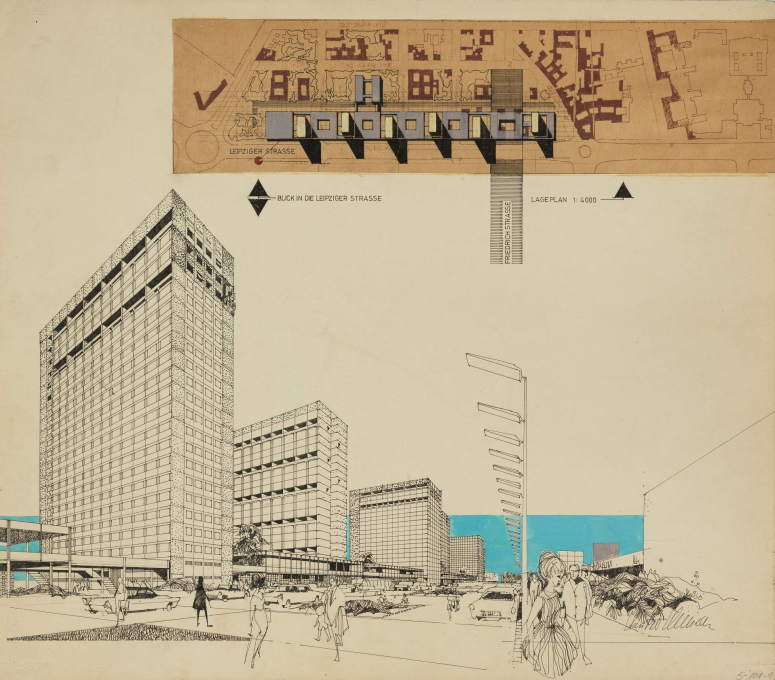

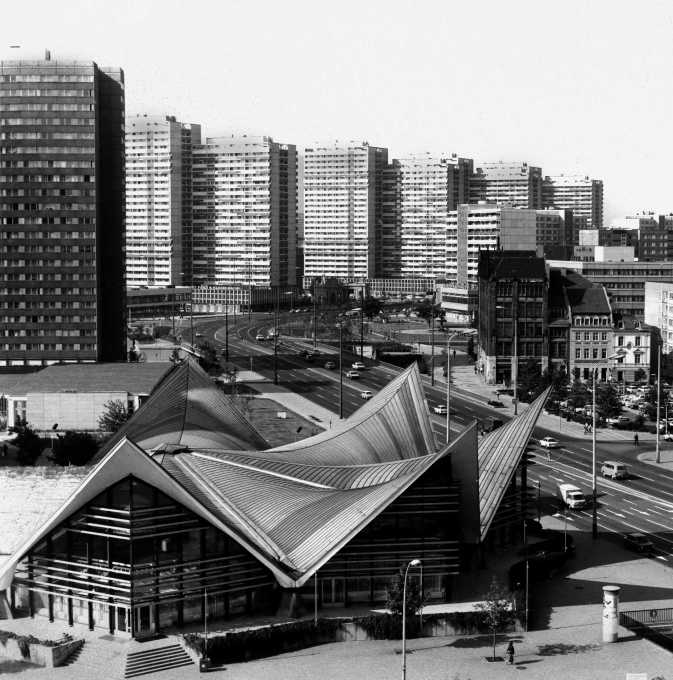

Characteristic for both halves of the city was the focus on the city centre, which needed to be revitalised. Large, dense structures were erected, such as the Europa-Center at Breitscheidplatz in West Berlin and the Rathauspassagen at Alexanderplatz in East Berlin. The urban plans for both of them clearly reflect the future-oriented creative drive of this era. Their construction signalled a new, open approach to spatial composition with wide, separate transit areas for pedestrians, cars and trams. Bordering these open spaces were individual buildings, loosely grouped in graduated elevations. While Alexanderplatz was being built, site-specific works by artists and designers were integrated into the creation of public spaces. The overall artistic concept extended from the colour of the buildings with their murals to the embellishment of the plaza with the World Clock and the Fountain of International Friendship as well as the spiral pavement design. Unfortunately, due to diverse modifications over the years, the original designs of these city centres are no longer fully recognisable.

Was modernism in the 1960s in Berlin as “radical” as the exhibition title suggests?

I think so. The reconstruction of the traditional city was vehemently rejected for political, economic and social reasons. Nothing was to be a reminder of the Nazi dictatorship and the terrible events of the Second World War. Architects and planners saw the ruined city as a chance to make a radical restart. Because of the frontline city situation, both sides tried to distinguish themselves from one another in the implementation of their ideas. This is especially evident in the public art: while the West expressed a more abstract approach to international modernism, in the East it was the ornamental façades, statues and social realist murals that transmitted the state ideology in the urban space. This can certainly be considered a “radical era”.

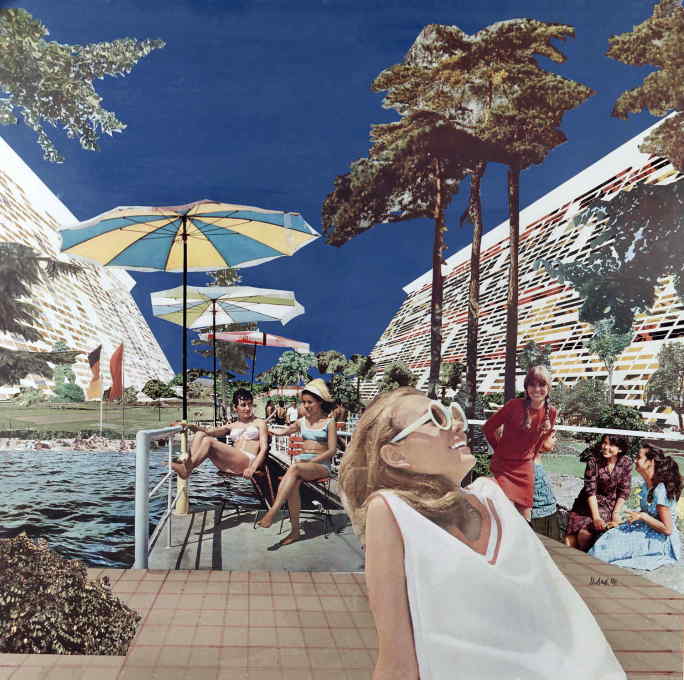

The exhibition also presents eccentric, utopian proposals, including mountain-like residential complexes, moving walkways, “backpack toilets” and giant “Intrahouses”. You address the enthusiasm for cars and roads and the massive road and infrastructure planning. In retrospect, not only do these plans exude a cheerful embrace of progress, they are almost alarmingly naïve. In this context, might there also be something foreboding in the title “Radically Modern”?

Indeed, the title connotes more than an expression of futurist euphoria. It also includes that ominous feeling which can result from the annihilation of a bygone building reality and the memory loss that accompanies it. That some of the architectural visions may seem naïve today might also derive from the pronounced “can-do” attitude that they grew out of. The planning climate and technological progress at the time made everything seem possible – that’s why so much went in a direction that might seem naïve or threatening, given our knowledge today.

The 1960s were also marked by a growing criticism of modernism and its urban planning, particularly in Berlin. Jane Jacobs in the United States and Alexander Mitscherlich in Germany were known for their popular positions against the demolition of the old city and the construction of new satellite cities in the suburbs, calling instead for a renovation and re-use of existing structures. Does the exhibition address this criticism?

Yes. We present an exemplary spectrum of such dissenting voices in various parts of the exhibition. We include notable architectural positions such as those of Georg Kohlmaier and Barna Sartory, as well as books such as The Inhospitality of Our Cities (Die Unwirtlichkeit unserer Städte) by Alexander Mitscherlich and Jane Jacobs’ The Death and Life of Great American Cities. We are also screening the almost forgotten film The Murdered City (Die gemordete Stadt) by Ulrich Conrads, which was produced for German television in 1964/65, but was publically aired only once. The screenplay was based on a recently re-issued book by Wolf Jobst Siedler and Elisabeth Niggemeyer, which – like the German translation of Jane Jacobs’ book – was an immediate bestseller. They all document the criticism of the times, but we also draw attention to the architectural debates, especially in the West, which increasingly addressed issues surrounding social relevance in architecture. As we now know, what began in the 1960s as an apparent criticism by an intellectual minority was, in fact, the start of a major crisis in modernism.

What can exhibition visitors, and Berlin itself, learn from this retrospective that could be applied to the city now and in the future?

Our exhibition calls for the selective preservation of this rather unappreciated building era. By confronting and analysing the cultural conditions at the time, we can try to understand the architects’ motivations for creating these buildings. Many important constructions from the 1960s in Berlin have already disappeared, while others are threatened with demolition or alteration. An important stage in the parallel architectural developments of East and West Berlin from the Cold War years is being obliterated. And given the current demand for affordable housing, it is crucial to re-examine the discourse surrounding industrial building concepts from that era. Unfortunately, the widespread rejection of the architecture and urban development from that period means that many of the promising approaches that were undertaken in Berlin have also been lost.

– Interview by Florian Heilmeyer. Translation from German by Alisa Anh Kotmair.

– Ursula Müller is head of the architecture department of the Berlinische Galerie – Museum of Modern Art, Photography, and Architecture. She is the chief curator of the exhibition Radically Modern. Urban Planning and Architecture in 1960s Berlin. The exhibition is accompanied by a comprehensive catalogue, a blog, an app and a symposium at the Technical University Berlin on 26 June 2015.

Radically Modern. Urban planning and architecture in 1960s Berlin

May 29 to October 26, 2015

Berlinische Galerie

Alte Jakobstraße 124–128

10969 Berlin

Germany

uncube are media partners of Radically Modern. This article is part of our mini-series of articles dedicated to the question as to whether architecture and urbanism in East and West Berlin in the 60s were particularly “radical”. Other articles encompassed revisiting East Berlin’s TV Tower or West Berlin’s FU Berlin; interviews with Daniel Libeskind and Georg Kohlmaier, inventor of moving walkways through West Berlin (unbuilt), and an essay by Dirk Lohan, grandson of Mies van der Rohe, who commuted from Chicago to West Berlin in the 1960s whilst he was supervising the construction of Mies’s Neue Nationalgalerie.