In winter 2002-03, the Austrian artist Oliver Croy and the German architecture graduate Oliver Elser took a road trip through the States to make a documentary about the architecture of communes and alternative communities. Elser describes here a selection of highlights from their tour and, for the first time, makes their film Counter Communities available to view in full online for uncube readers.

Can alternative ways of living give rise to alternative architectures? While this question was the starting point for the film Counter Communities, it can’t be said that it was ultimately answered with a resounding “yes”. Our film, which initially had the working title “Hippie-tecture”, was shot in the United States, where numerous communes and alternative communities established since the end of the 1960s have also been trying out new approaches to architecture. The most notable such project was Drop City, a kind of high-tech commune that became a rusty skeleton of its former self when its social structure rapidly disintegrated. Yet some examples of counter communities with strong architectural ambitions have endured. The Lama Foundation survived a devastating fire and re-created itself. Meanwhile, Arcosanti, the ideal city established by late architect Paolo Soleri, demonstrates the ambiguity of dogmatic planning, as it soon became home to a kind of counter-utopia that was much more popular with its young volunteers. The Earthships of Mike Reynolds, on the other hand, left behind their wild beginnings so that the earth sheltered, rammed tyre constructions could be purchased as finished, single-family homes. The newest project depicted in the film shows how a counter community of homeless people actually needed a strong utopian image in order to be accepted: a settlement of white Buckminster Fuller domes in the heart of downtown Los Angeles.

Arcosanti

Paolo Soleri (1919–2013) rejected the continuous sprawl of American cities. So in 1970 he moved to the desert of Arizona and founded Arcosanti, a real-life utopia, envisioned as a dense city for about 5,000 residents. The idea was to create urbanity through density, financed through donations, rather than investors. When the film team visited Arcosanti in 2002, around 60 people were living there.

From his mentor, Frank Lloyd Wright, Soleri got the idea of involving student volunteers in the construction process, and a small, photocopied handbill, “Become a Volunteer at Arcosanti”, was distributed at architecture schools around the world. Arcosanti is an architect’s dream in concrete: a small anti-city. Once a week, the master would ride out from Cosanti, his whimsically beautiful cement garden in Phoenix where he lived and worked, to make his rather quirky appearances in Arcosanti. Construction operations had long been professionalised, with a troop of Italian construction workers who ensured that at least a bit of building went on. The volunteers, all college students, practiced agriculture without tractors, helped in the kitchen or cast the bronze bells that were sold to tourists.

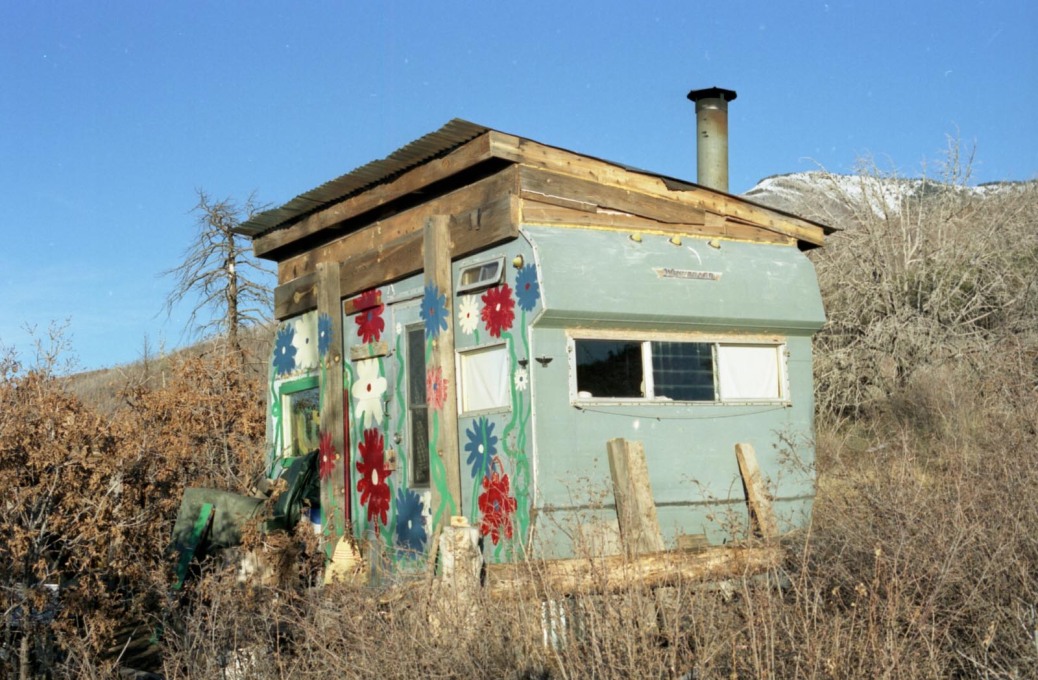

Like the Acropolis, Arcosanti is built atop a cliff; the college kids, on the other hand, were living in the anti-utopia in the valley below. Their “camp” consisted of precast, three cubic metre concrete cubes. These previous test structures for the looming Acropolis-like structure, have since been anarchically altered, colourfully painted and protected with roofs from the rain. The young people enjoyed living down in the camp, where it is green and they can do as they please. But they were also committed to helping Acrosanti slowly but surely grow, even if it meant peeling potatoes for the many visitors. As to whether or not they wished to trade places with the inner circle of Soleri disciples living above, the answer was “no”. Instead, they chose to remain in this alternative to the alternative world that Soleri had conceived. The “urban laboratory” was a place to study how utopias produce anti-utopias, and how planning can kindle the faint whiff of anarchy.

Earthships

In the 1970s, Mike Reynolds was lying in one of his self-built concrete pyramids when he had a revelation. “Wizards” appeared to him in a (possibly drug-induced) vision, instructing him to impart his life with new meaning and so Reynolds became a “garbage warrior”, as filmmaker Oliver Hodge called him in his eponymous film made a few years after Counter Communities.

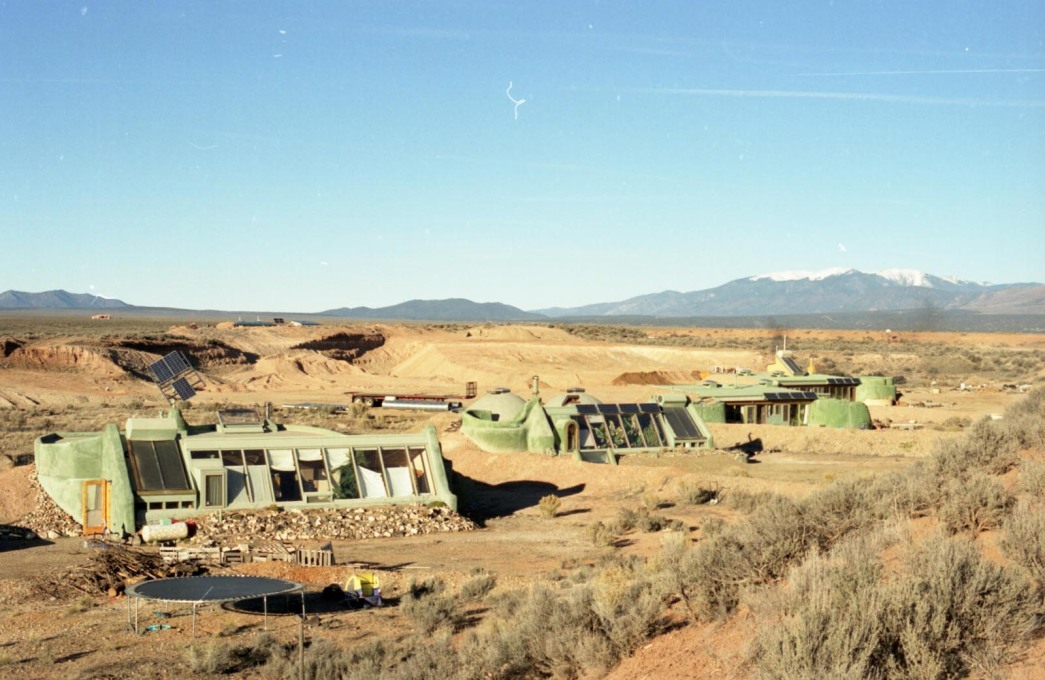

Reynolds started building small, domed dwellings using old tin cans and empty glass bottles. In the years to follow, he honed his building designs using everyday trash, discovering that used car tyres could be found practically everywhere and in large quantities. Filled with rammed dirt, they became solid walls, and settlements could be established in remote locations. A spade, a sledgehammer and a pickup truck filled with car tyres was all that was necessary to construct a building shell.

Ever since the publication of Henry David Thoreau’s book Walden in 1854, the notion of living a truly independent life has inspired countless alternative movements in the United States. Reynolds’ Earthships were built on undeveloped plots on the New Mexican plateau, just a few dozen miles away from the Lama Foundation (below). On parcelled plots Reynolds showed new settlers how to build their own Earthship by hand. There are no external energy sources or water supply, electricity is generated by solar or wind power, water is harvested from the sky into cisterns, and waste water is filtered by plants in a botanical cell. The Earthships are also sunk into the ground for added insulation against the cold.

However, parked in front of most of the homes is a gas-guzzling SUV, used to fetch groceries from the nearest supermarket, many miles away. Looking as if they could be from the film set of Mad Max, the Earthship settlements are composed of single-family homes. The self-build ethos of the early settlers has led to the development of entire off-grid communities. Meanwhile, Reynolds also offers completed Earthships for sale, which can be purchased like any other home, just in an amazingly beautiful landscape.

Lama Foundation

In 1968, a group of New York artists moved to a mountainous area near Lama, New Mexico, in order to found a spiritual commune. Their first building was made out of adobe brick with the help of local Indigenous Americans. The geodesic dome over the central meditation hall was designed by Steve Baer, who had previously worked at the Drop City commune in Colorado. His legendary Dome Cookbook was the Lama Foundation’s first publication.

In addition to the community buildings, there were also a number of minimalist houses built on the premises, which were used for sleeping and retreat. The Lama Foundation was quick to recognise that too much proximity was often detrimental to communes. During the day, living, working and meditating took place together. But in the evening, individual families and couples could retire to their small, isolated dwellings spread throughout the woods.

A fire in the late 1990s destroyed a majority of the often lovingly designed homes. While the number of residents has since decreased, those who remained have hosted annual architecture workshops to help to rebuild the commune. Some of the individual houses are rented out as “hermitages”, where visitors can withdraw for a few days in complete solitude. Meals are provided at a drop-off point by Lama residents, who earn a part of their income this way. While the houses are experimental, the form of settlement, with its scattered single-family homes, follows a conventional, proven scheme.

Dome Village

Just a stone’s throw from the skyscrapers of the Downtown Los Angeles financial district was Dome Village, a community for the homeless that was founded in 1993 by activist Ted Hayes. The settlement of 20 dome-shaped “Omnispheres” was erected with the help of sponsors in a parking lot next to a freeway onramp.

The prefabricated domes were designed by Craig Chamberlain, a former student of Buckminster Fuller. Costing around USD 10,000 each, they were initially intended as emergency quick-build shelters, for example for disaster relief workers. The interior was divided to provide living space for two homeless people for a year.

Dome Village was originally intended as a short-term pilot project, but the experimental self-managed settlement met with positive response. Although the number of inhabitants was small in comparison to the number of people living on the streets of Downtown LA at the time, Dome Village became a platform to draw attention to homelessness and also served as an effective counter-model. As Ted Hayes put it: “if we had erected barracks, no one would have noticed. But this way, it got the attention of people who were attracted by the bright, white domes, who asked if it was a NASA project.” In 2006, the owner of the parking lot denied the renewal of the lease, and Dome Village was dismantled.

– Oliver Elser is a curator at the Deutsches Architekturmuseum (DAM) in Frankfurt and uncube correspondent.

For more on alternative communities and all things communal read uncube issue no. 34: Commune Revisited and watch the Counter Communities documentary in full length here:

Counter Communities from uncube magazine on Vimeo.