Is the use of narrative and storytelling in the design and presentation of a new building, just a way of spinning woolly, fluffy words around a cold, hard sell? Or a useful way to add conceptual flesh around a scheme to capture the imagination – and money – of a potential client or future user? Cued off by the recent debate Selling the Dream at the Architecture Foundation in London, which “investigated the role of storytelling as an architectural tool”, Ellie Duffy considers the use of storytelling in the business – and art – of architecture, and finds tales both tall and cautionary.

Bjarke Ingels is on screen, explaining in an online launch the narrative behind BIG’s designs for a new World Trade Centre tower. He’s like a magician in the film, conjuring animated diagrams out of thin air against the Manhattan skyline to explain the stacking boxes concept of his building, which will eventually house Rupert Murdoch’s Fox and News Corp companies. In the background the architect’s tower materialises in front of our very eyes so that, before it’s even off the drawing board, there it is, in the virtual world of the promo, complete and animated with off the peg narratives of everyday life being performed by its happy virtual inhabitants.

Reaction to the film has been mixed, with the UK’s Architecture Foundation tweeting in response to its launch “another round of urban gibberish wrapped in the language of contextual response”. The real question, though, is will Bjarke Ingels’ story stand the test of time? What happens afterwards when an unbuilt building has been constructed virtually and is then virtually furnished, landscaped, and populated before our very eyes? Will it virtually age a bit, start falling picturesquely into decay even?

Something of a cautionary tale in this respect emanates from the UK in the – rather ungainly – form of Rafael Viñoly’s 20 Fenchurch Street office building in the City of London. Designs for this bulky tower – dubbed “the Walkie Talkie” – were ridiculed by many critics (uncube's Klaus included) long before completion, with one dismissing the proposal memorably as a “diagram of developer greed” – not exactly framing a narrative that, one assumes, either the architect or developer planned. On completion the building suffered further ignominy. First it became an actor in its own schlock horror story, when its concave façade led to a much-publicised “death ray” heat build-up in the summer streets below, from the sun’s reflection. Later its public space, or “sky garden”, was mocked by journalists for spectacularly failing to live up to the expectations raised by over-ambitious computer generated imagery in earlier puffed-up press releases.

Conversely a recent UK TV documentary unveiling the story behind artist Grayson Perry’s recently completed “House for Essex”, designed in conjunction with the architects FAT (whose Charles Holland we interviewed about the development of the project), seems to have met only with interest and respect in the UK media. The design is based very literally around the life story of Julie, a fictional everywoman from the county of Essex – a character made up by the artist – whose life and untimely death is memorialised by the house. Both the artist’s story and the building appear to have won over not only the UK press but also a local community initially in opposition to the flamboyant design.

Are these divergent reactions to specific examples of architecture simply about their design or do they have something to do with the nature of the narratives constructed behind them? Perhaps ultimately it depends on who’s telling the story – and who the audience is, or rather, is intended to be?

Last week in London a developer, an architect and an urban planner related their experiences of working with narrative in architecture at a panel event organised by the Architecture Foundation. A journalist, Zoe Williams of The Guardian, set the scene by describing an “austerity Britain” in which architecture is being increasingly offloaded by the state to the private sector. Aesthetic quality (or any level of quality) in the UK civic environment is now viewed by definition, she argued, as demonstrably not delivering value. Meanwhile a booming private housing market, in London at least, is dominated by buy-to-let investors, many residing outside the UK.

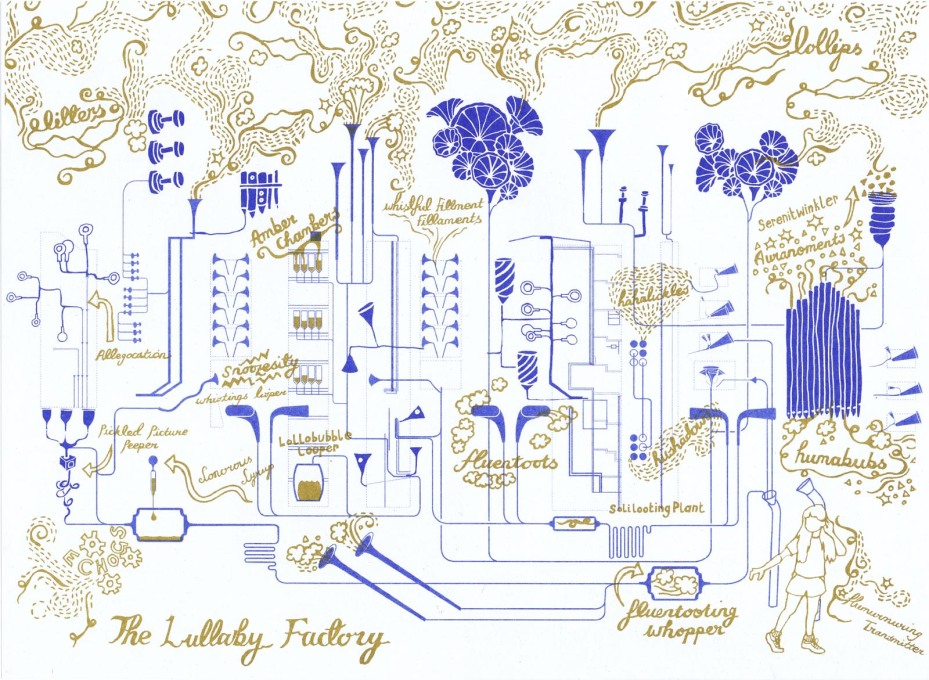

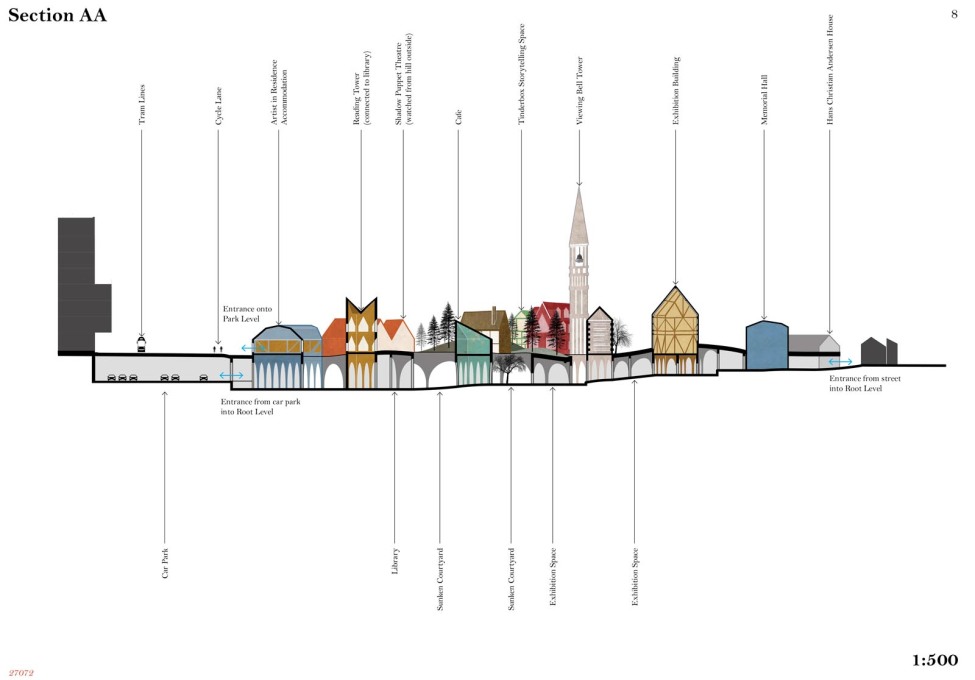

The architect on the panel, Maria Smith of Studio Weave, explained how narrative is used in her practice to create projects such as “The Lullaby Factory” for a London children’s hospital, or an earlier pair of pavilions at Kielder Water in Northumberland. The main reason for storytelling in her work she says is to disseminate information in the early design stages in a way that’s memorable – to sell her design concepts, if you like, in eminently repeatable terms to an ever-widening circle of participants: clients, planners, stakeholders, users. She also made the point that stories allow architects to express design intent in non-static ways that images of completed buildings simply can’t achieve. Things become more problematic, she says, when stories are used to justify design. Instead they need to be integral to the design development process, avoiding the realms of post-justification. Narratives in architecture, she warned, can be used to circumnavigate the real problems.

The developer, Martyn Evans of Cathedral, described how he has used storytelling to decide what to do on “difficult” (read cheaper) regeneration sites. He has on his hands, for instance, a relatively small plot of 20 acres bordering another developer’s vast projected housing scheme of glass and steel towers in Greenwich, London. He knows he can’t compete on those terms so he needs a good story (and good architecture for that matter) to differentiate his scheme and persuade people to buy his flats.

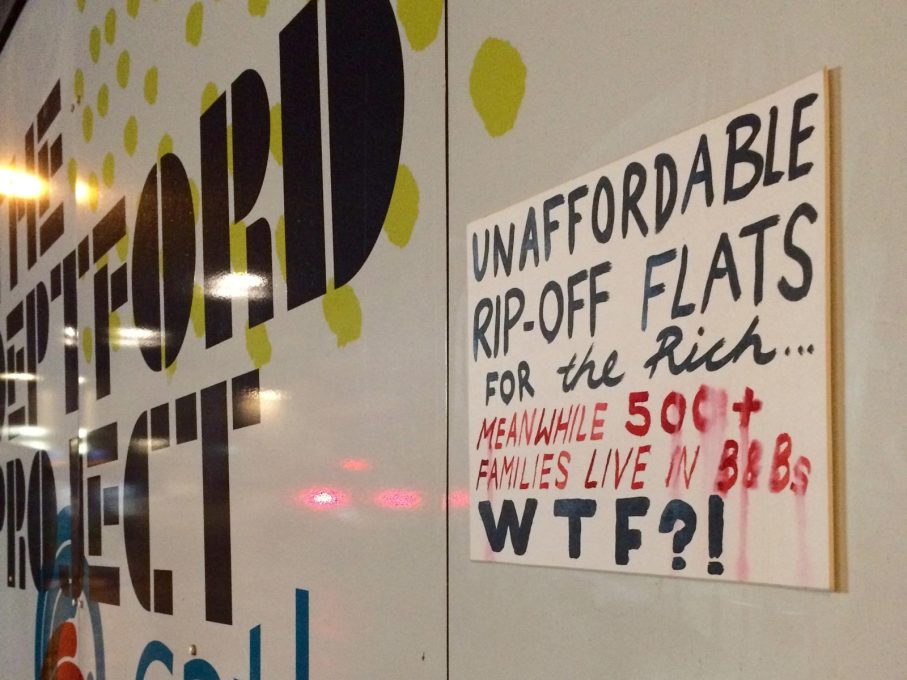

Evans described walking sites with architects, trying to envisage the kind of places where people might want to be. But development is complicated and even he admitted that he can’t always control the trajectory of the story: he spent six years with a collection of architects developing the Deptford Project, a mixed-use, medium-scale development in a neglected area of London. His work there included creating meantime uses for local businesses and community-focused events. As it happens the housing element (by Rogers Stirk Harbour) was completed first and was marketed for sale to overseas buyers. A promotional video extolling the investment potential of the location was picked up by the press and Evans was subsequently trolled on Twitter for selling out the community he had so carefully nurtured.

The urban planner, David West of Studio Egret West, has worked with Evans and Cathedral on several schemes including The Old Vinyl Factory, another mixed-use scheme created out of the infrastructure of a former 17-acre business park in Hayes, West London. As masterplanners, Studio Egret West worked to create a binding design narrative for the massive site with a story forged around the site’s history as a world centre of vinyl record production. The branding may be a little heavy-handed, but you can see how in this kind of context such a narrative could help weave together a coherent sense of place.

But West, too, sounded a note of caution. At Caxton Works, another Cathedral scheme in London, the developer and architect attempted to create something for which the market – it transpired – was not prepared to wait. Their story there was about a new type of unfinished warehouse living space, generous in scale and space. An evolutionary narrative planned to integrate existing business tenants and built fabric into the scheme. But it seems there’s no space for time in the current London housing market. Money, apparently, took over and the scheme design was sold on to be realised by another developer and another architect (80% sold off-plan within three days of marketing).

It seems that architects and developers need to be careful about the stories they tell as they design, secure planning and market their buildings. The public – the recipients of architecture – aren’t daft. People are wary of where stories come from and are highly attuned to the motivations behind them. Everybody loves a good story but the particular combination of finance, free market economies and architecture, it appears, tends to result in narratives that lack the ring of truth.

– Ellie Duffy is a director of the graphic design agency Duffy, London. @duffydesign

architecturefoundation.org.uk

big.dk

2 World Trade Center in New York City, a BIG design, Squint/Opera production from BIG on Vimeo.