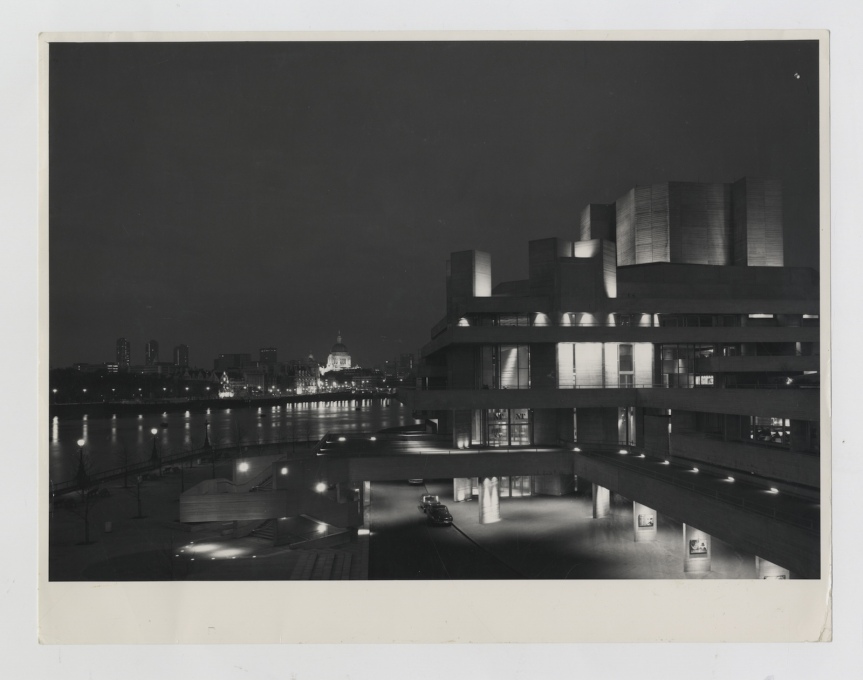

By the time that Denys Lasdun’s National Theatre opened in London in 1976, it was greeted with public disdain. Brutalism was out of fashion and the South Bank where it stood was still a relative cul-de-sac, surrounded by bombsites and with no Thames Path linking it to the East along the River. Nowadays the theatre is one of London’s most distinctive cultural buildings, its board-marked concrete harking back to an age of sculpturally bold, civic architecture. Coinciding with a new public appreciation of mid-century British modernism, the theatre has recently undergone a major refurbishment, NT Future, by architects Haworth Tompkins. uncube’s George Kafka caught up with Patrick Dillon, who was the project’s lead architect and is author of a new book on the building, Concrete Reality, to discuss the National Theatre’s complex history.

How did the NT Future project come about?

The National Theatre (NT) was starting to look very dowdy alongside the adjacent Southbank Centre, which had been successfully refurbished by Allies and Morrison in 2007. This had also had the effect of encouraging people to start fully using the Southbank as a cultural and social hub, finally fulfilling the original intentions of the 1940s Abercrombie Plan.

This also highlighted the real problems the National Theatre had in its context. When Denys Lasdun designed the building there was no river walk east of it, and only a bombsite behind, so at the time it made sense to only open up to the north-west, with the rest of the building closed off as the public never usually approached it from other directions. Now twelve million people a year are going up and down the river walk and half of them are approaching from the east– from Tate Modern and the Millennium Bridge. They were arriving at the National Theatre service yard, giving off the wrong signals for an organisation and building that’s all about openness and welcoming the public.

The NT’s own operations have also increased over time: with more shows and more touring shows like War Horse and One Man, Two Guvnors. These require a huge workshop operation to sustain them and the NT workshops were just too small. So a whole range of issues around the National Theatre’s public space and public perception needed addressing so that, in Nick Hytner’s [former Artistic Director of the NT] words, we could “make people love the building as much as the National Theatre company”: a good motto for the whole project.

Describe the process of the renovation. What were the major challenges you faced and how much of Lasdun’s original vision for the building did you have to take on board?

Working with an existing building, particularly one of such personality, requires a heightened level of thinking, analysis and creativity. At the same time, you can’t do anything which is outside the orbit of that building: you can never step away from its rules. Fortunately for us, Lasdun’s rules in conceiving the building were very crisp and strong. One example is the way he used materials; the whole building is made out of concrete, stainless steel, dark wood, carpet, engineering bricks, and that’s it. Lasdun used this palette rigorously throughout the building. If one traces this hierarchic logic in his use of materials, then the decisions involved in following that logic through become very clear. In the work we’ve done we haven’t touched Lasdun’s concrete, the primary material in this hierarchy, working only with secondary materials like the timber screens.

The other thing that guided us was our understanding of Lasdun’s original conception of the building. Reading what Lasdun wrote and said about it we were always convinced that the National Theatre was conceived very much as a democratic building, standing out against the previous theatrical tradition that was all about class, status and hierarchy. Lasdun was trying to make a piece of city that would welcome people in. So while we knew that public perception had tended to see the NT as forbidding and fortress-like, all the ingredients in terms of public welcome and openness that we wanted to achieve, were already there. That gave us a lot of confidence in trusting Lasdun, as it were: going back to his thinking to find the threads we could pull to achieve the kind of outcome the NT wanted.

Where do you think the National Theatre’s reputation as something unwelcoming and fortress-like came from?

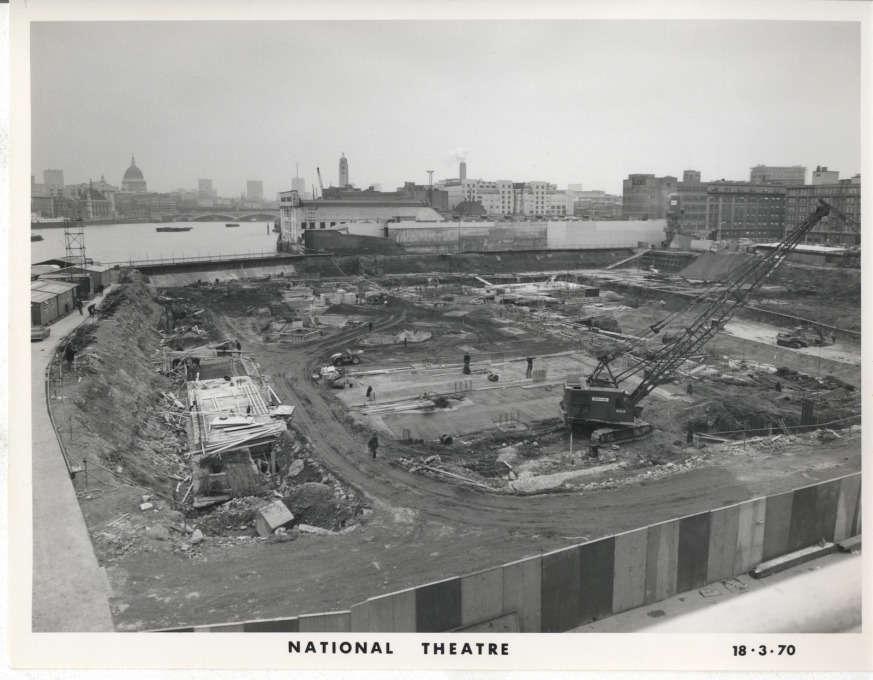

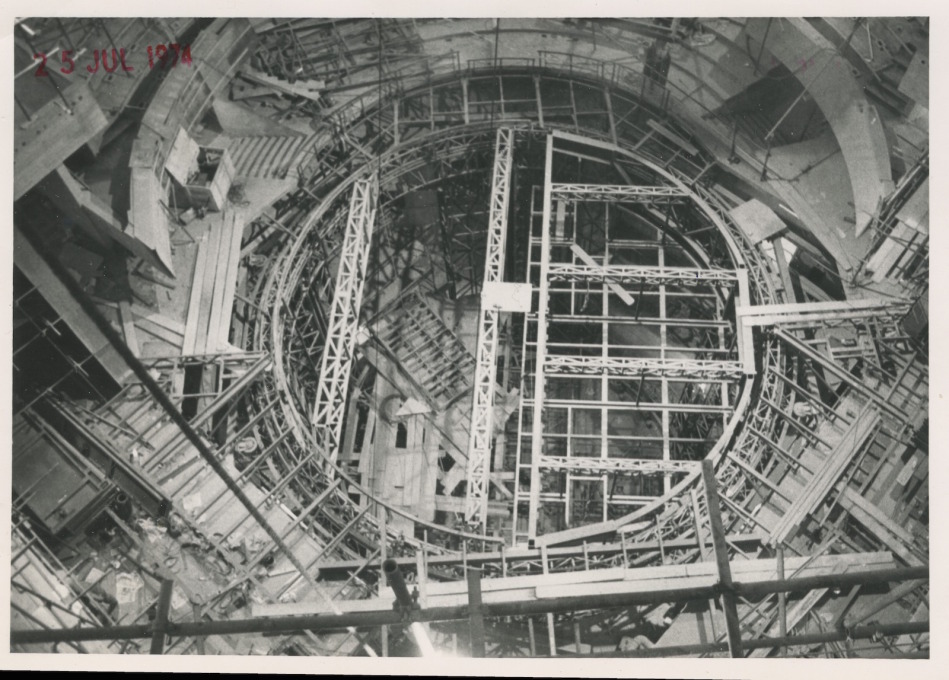

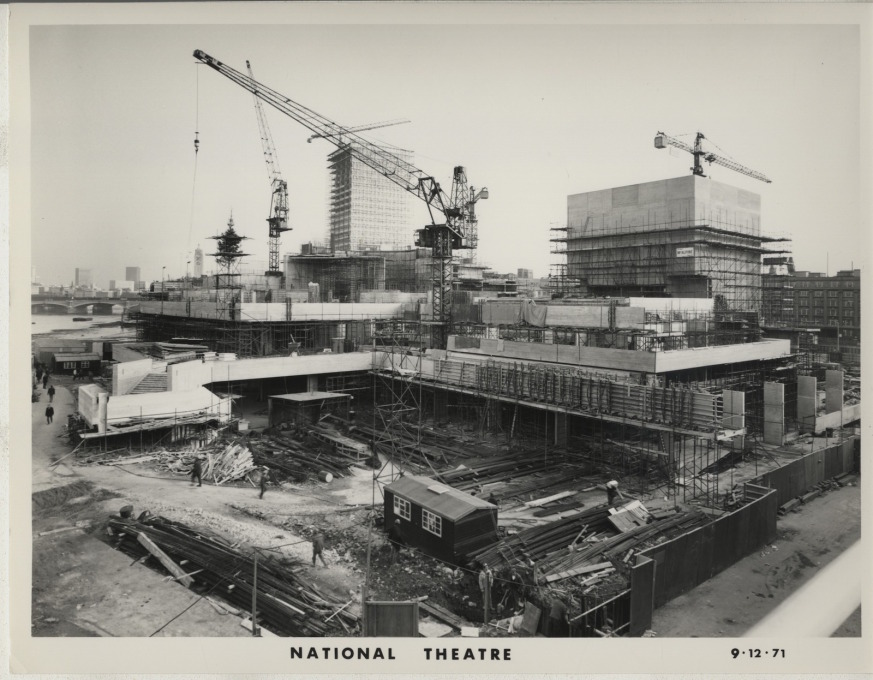

The key thing was that it was incredibly unfortunate in its timing. Denys Lasdun was commissioned in December 1963 and if you’d taken a snapshot of public perception at that point, his mid-twentieth century heroic modernism would still have been seen as something extremely exciting. But after long delays in the design, fundraising and an awful construction process, when the building opened in 1976, the public mood had swung completely away from this sort of cerebral, abstract, concrete construction: the building was already seen as obsolete. By then the public had started to associate concrete with poorly produced and maintained social housing. So even though the National Theatre, both in the quality of its construction and in the profundity of its design, had nothing to do with those housing schemes, it became a kind of lightning rod for attracting public opprobrium, being the most prominent concrete building of all.

The NT Future project and your book/exhibition Concrete Reality seem to coincide with a wider reconsideration of mid-century modernism and brutalism occurring in the UK and among the public – along with the National Trust’s Brutal Utopia tours, the redevelopment of Preston Bus Station, new books on brutalism and so on. Why do you think the rethinking of these movements is happening?

Partly it’s just the passing of time, the falling away of the negative associations with the concrete housing I mentioned. But it’s also a new appreciation of the work of a large group of mid-century modernist architects who produced extremely socially minded, idealistic work – some really fantastic buildings. The strength of the original thinking, its openness, radicalism and robustness, are all qualities now finally being enjoyed and appreciated. We’re starting to rediscover the excitement of mid-20th century modernism, starting to seeing the qualities of the best examples.

It’s also been helped by the timidity of a lot of contemporary architecture by comparison. What architects have done since the end of postmodernism has been very elegant, well put together, well thought through, but nobody’s being as brave as Lasdun was – or Chamberlain, Powell and Bon were at the Barbican, or BDP with the Preston Bus Station – particularly not in a sculptural way. Those are really bold, gritty, almost baroque buildings. These qualities are missing in architecture at the moment – even Zaha’s brand of sculptural architecture is much slicker and smoother.

You’ve avoided the word brutalism in reference to the National Theatre – why is that?

I don’t think the National Theatre is brutalist. It uses raw concrete, béton brut, which is the root of brutalism. But its thinking is entirely classical. Its order, symmetry, and compositional techniques are very much grounded in the classical past. Indeed the finesse with which Lasdun used concrete turned it away from how Le Corbusier had used it: as something to shock, playing up its rawness. Lasdun was doing something different: turning board-marked concrete into a material of great finesse, with great care put into the detailing of the boards’ layering, the way they met at junctions and so on. It wasn’t about shock tactics at all, but about creating a beautiful and carefully mannered surface. What excited him about concrete at the NT was it being an industrial material, turned into a luxury material by the way it was handled. Through this material the building is at once both a factory and a palace for theatre.

Which is your favourite space at the National Theatre?

It’s got to be the ground floor Lyttelton foyer. There you see one of the core compositional ideas of the building: the way the axis of the Lyttleton Theatre clashes with that of the Oliver Theatre upstairs. You get this baroque space where different columns and planes are at differing angles to each other, all bathed in light coming off the river to one side, while the diagrid – the concrete waffle slab which runs across the ceiling – picks up all these shadows. It’s like being inside one of Piranesi’s etchings. It’s an absolutely brilliant space, whether you like modernism or not.

- Interview by George Kafka

- Patrick Dillon is an author, broadcaster, curator and architect specialising in historic buildings. He restored the Benjamin Franklin House in London and led the team regenerating Snape Maltings, home of the Aldeburgh Festival. His latest book, Concrete Reality: Denys Lasdun and the Architecture of the National Theatre is accompanied by an exhibition which runs until 15 November.