There is perhaps no one outside the firm more familiar with Zaha Hadid’s built oeuvre than architecture photographer Hélène Binet. For the past 30 years she has shot most of Hadid’s buildings, both completed and under construction. For our current issue, she has compiled an exclusive selection of Hadid-under-construction images, offering us a glimpse behind the scenes and revealing the enormous effort that goes into creating her light and fluid forms. Here on the uncube blog, we present an extended version of the photo essay you can find in our current magazine issue no. 37: Zaha, along with the full interview with Binet.

Hélène, you have a tremendous archive of images of almost all of Zaha Hadid’s buildings, following their construction and after completion. How did this all start: When did you first meet Hadid and how did it come to pass that you started documenting her buildings?

I think it started in 1988 when she had an exhibition at the AA [Architectural Association, London] about her work, which was mostly furniture and drawings back then, and I was involved at the AA and took some images of the exhibition. It was Alvin Boyarsky, who was then dean of the AA, who brought us together. He was an important figure because he was interested in architecture, art, design and photography and constantly trying to bring the different disciplines together. He also was among the people who convinced me to go to Berlin and shoot my first images of architecture there. Before then, as someone coming from stage photography, I hadn’t dared to venture into architecture. By coincidence, Zaha liked my photos and sent me to Weil am Rhein where her very first project was under construction, and so it happened that her first commission turned out to be one of my first commission as an architecture photographer, too.

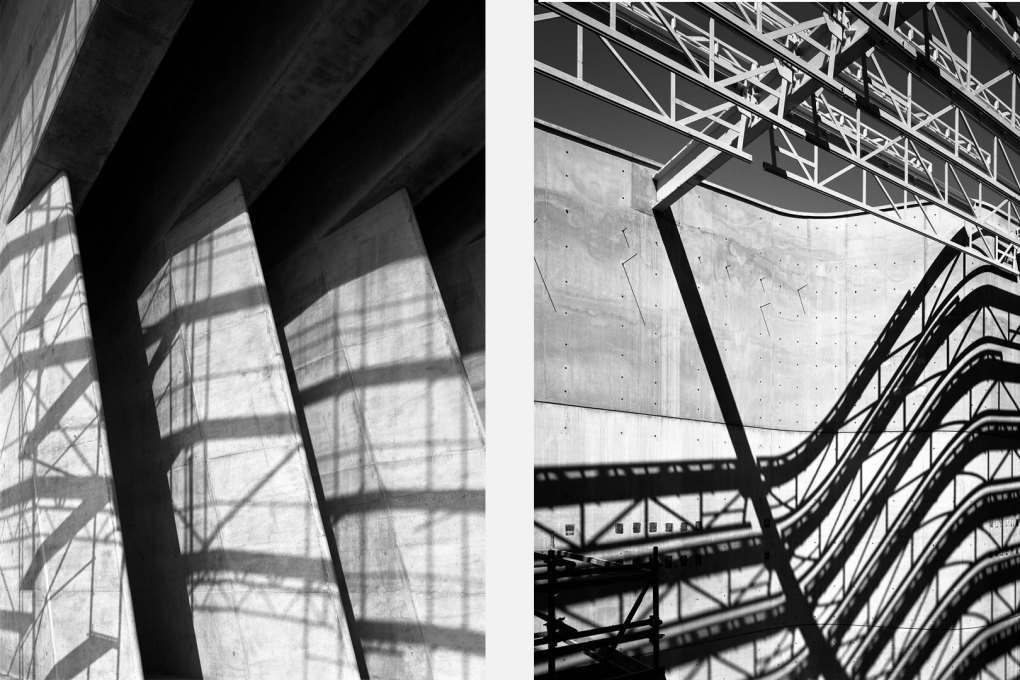

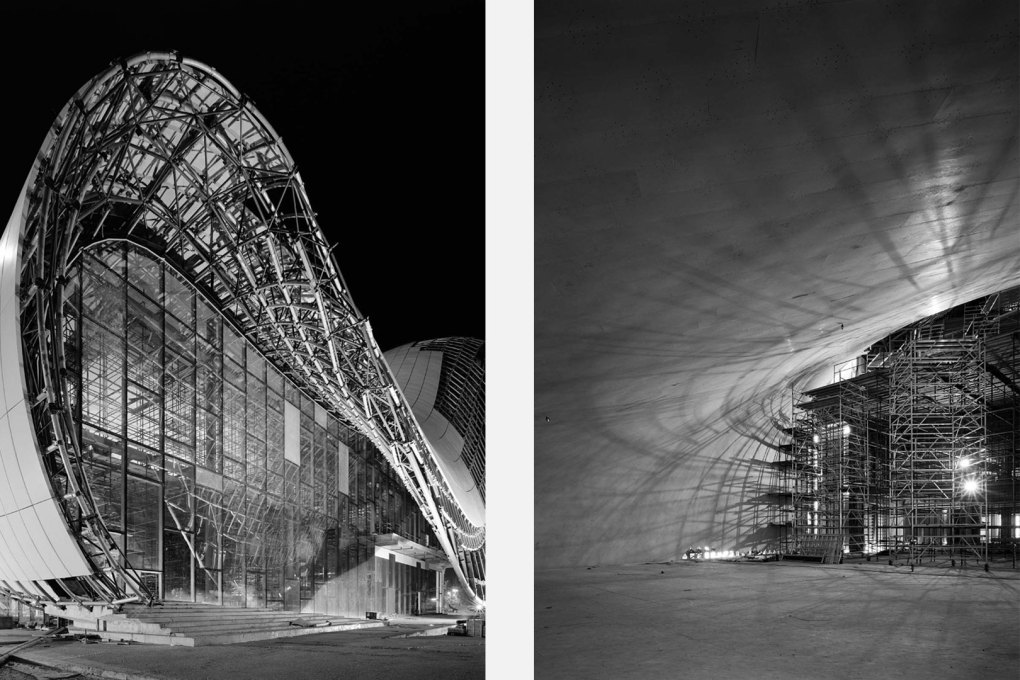

The construction was absolutely amazing. She was already stretching technology, stretching the imagination about what was possible to build at that time. She was working with concrete in a really amazing way, and my photos were a spontaneous reaction to what I experienced and saw at the construction site. This is how our relationship started and at the same time how my fascination with the construction of buildings started.

Since then, it seems as if you have taken images of all the buildings Hadid has ever done?

No, no, I don’t think so. Maybe in the beginning up to a certain point in her career, but in recent years she has built so many projects all over the world that it became impossible for me to shoot them all.

How do you choose which of her buildings you want to photograph?

Whenever there is a project where Zaha is pushing the boundaries and limits of building technology and our imagination of what is feasible, and when there is a specific moment when this pushing of the boundaries becomes visible on the site – when you see the cast concrete or the steel structure of a building – then I would go there. With some of her other buildings there is never a moment where you can see this process in a condensed form. Like with her museum in Cincinnati, where I only took images of the completed building because the construction didn’t reveal so clearly how the building was made. That’s what I am looking for: this moment when technology is stretched to its limits and becomes clearly visible.

So together with Zaha you select the projects that push the boundaries the most?

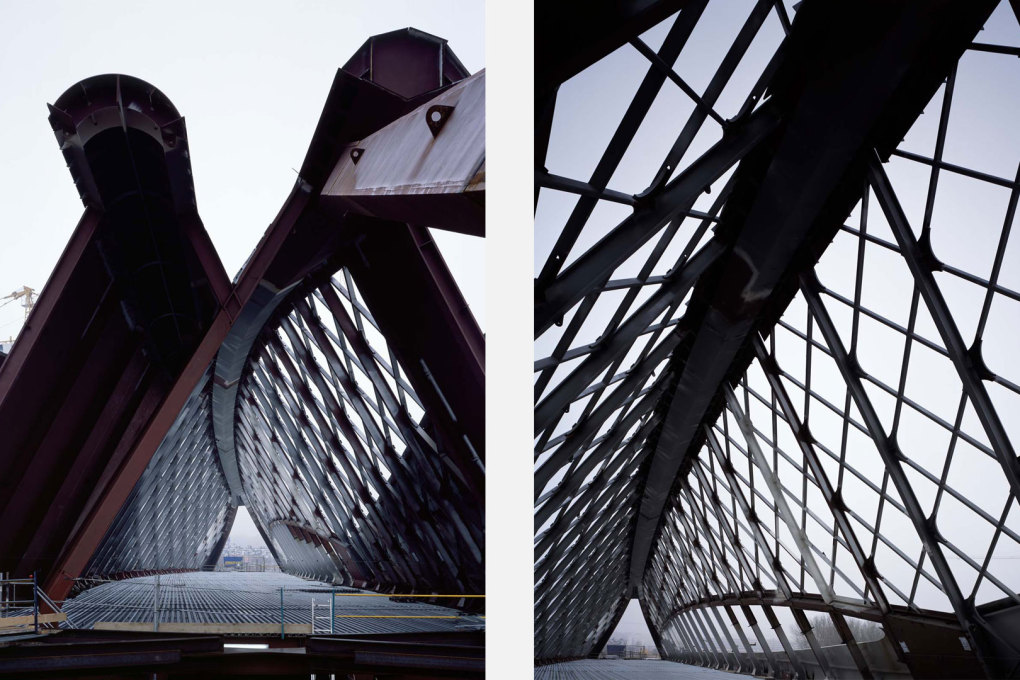

Yes. Recently I went to visit the construction of the port house in Antwerp [scheduled for completion in 2016], which had a very fascinating moment when you could see the new steel structure on top of an historic house – it’s a building coming out of another building, a really fantastic sight and experience. So when Zaha and her team think there is such a moment in the process of construction, they call me.

How do you prepare for your visits to the buildings? Do you try to learn as much as possible about the project before going, or do you rather let yourself be surprised by direct experience on site?

I always speak to Zaha and the project architect who is involved directly with the project. So yes, I do prepare before going, but I never have an established way of photographing a building before getting there. To use an extreme example I would say that Bernd and Hilla Becher had a very specific style in which they photographed architecture. I don’t work like that, because with every single building I want to know anew what’s behind it, its construction and technology. I react more instinctively. I have to let things sink in and evolve. Actually, I want to be surprised, so I am looking for that surprising moment or element.

When you get there do you try to spend a few days with a building before deciding when and what to shoot?

Well, it isn’t always possible, but my ideal working conditions would be that there is enough time to study the light and how it changes over the day. Which is even more difficult as I always want to know what’s happening on the other side of the building while I watch the light, so I have my assistant taking snapshots on the sides of the building I can’t see. Together we try to understand as much as possible what is happening at any specific time of the day. I like to say that the light of a building is like the clothing on a person. If you take a portrait of a beautiful person but put her in a terrible dress then something else comes out. Light is something that helps you reveal certain aspects of a building, making a clearer statement. Light is very important. Which also doesn’t mean that it has to sharp and clear light all the time, sometimes its better if it’s foggy or indirect, diffused light.

If you compare your work with portraying a person, are you then always looking to bring out the best aspects of a building, making them as beautiful as possible – trying to show them in their best light so to speak?

Well, not in the sense that I am trying to hide something – or sell them as something that they are not. But I am indeed looking to create powerful images to trigger your mind and imagination, so that you can think about the space even if you only see an image of it, maybe even evoking emotions about this space, which is of course incredibly hard if you’ve never really experienced this space or building. After all you are only looking at a photograph. I think that light is a very powerful tool to do that. When I was taking photos of Hadid’s bridge pavilion in Zaragoza I was looking for a little bit of foggy light to maybe evoke associations with other famous images in which we’ve seen daring new steel bridge constructions all over the world. There is a rich tradition of this type of photograph and as human beings we have an incredibly powerful imagination, which I am trying to related to – or touch with my photography.

Looking at the images in this photo essay I have the impression that you are very much focusing on the building as a single object rather than trying to put it in a direct relationship with its context.

You are right. Especially when I am taking images of the construction site, I am not interested in the context. I am purely focusing on the skeleton of the building. With all future elements like roof, doors, fire escapes etc. missing, I am looking for the core essence of the building. Maybe you get a glimpse of the context of a building, like the old building in Antwerp of course or the old factories in the distance in some of the images I took in Wolfsburg. But most of the time I am absolutely focusing on the structure of the building.

Was there one building of Hadid which made a particular impression on you when you first saw it in real life?

Certainly, it was Vitra’s Fire Station in Weil-am-Rhein. It was the first building of this kind I ever saw, it was a total surprise and seeing it at a moment where it was still being constructed was very fascinating. If I had to name just one other example, it would be the Aliyev Center In Baku, which was another big surprise.

Could you explain why?

The scale of the building in Baku was new. It’s the essence of creating a feeling of endlessness, where landscape and building are so attached to each other that you never really see a threshold in the building. Its an endless experience.

Do you discuss your experiences of her buildings with Zaha Hadid, do you think you share similar feelings about the spaces?

Actually we never talk about architecture or photography. When we meet, we speak about life. She is such a generous and energetic person, which in my opinion explains a lot about the energy and will behind her buildings. To me, this complexity of her persona can be found within her architecture, that’s also what makes it so specific and special. I cannot express this precisely, but of course you are influenced in your perception of a building if you know the architect who designed it so well in the first place.

I would imagine that Hadid’s spaces are extremely difficult to represent on photographically with all their non-regular angles, non-corners, non-forms ... do you agree?

Yes, I totally agree. The first instinctive reaction to her buildings always seems to be “oh this is so easy”, because they are so funky. Lets put it another way: if I had to choose an architect whose buildings are constructed in the closest way to how I compose my images, it would be Peter Zumthor. Like my images I have the impression that his buildings are calm, silent, reduced, focused. You can photograph a detail and it already contains the whole. This is a classical approach in photography, to look for a position where you can include a detail that gives you a good sense of the rest and the context. Now with Hadid’s work, all this is missing. It’s a feeling of endlessness … a continuous evolution … that every stage just leads you to the next. Trying to frame this is indeed very challenging, maybe sometimes even daunting.

But I think that’s one of the qualities of her work, and it’s a challenge I like. Basically, it is always an almost impossible challenge to frame a three-dimensional space, to translate any spatial experience into a two-dimensional format. It is only possible to point out certain aspects of it, certain associations and emotions and impressions. There is a big difference between a good photograph and the real experience of a space. Both are very valuable. I mean, a photo gives you a moment to reflect upon the space in a very different way, but we all have to keep in our mind that if you want to fully understand a space, you have to go there.

Do you see the images you have selected for this photo essay for uncube as a documentary of Hadid’s work?

No. It’s my statement on the aesthetics and the making of form. I have selected those where I see this moment when the construction of the building as an essence of the architecture becomes most clearly visible. There is such an aesthetic in how a building is made, how you pour the concrete and assemble the steel, and I want to show the beauty of this moment.

Your images introduce us to the immense efforts which are sometimes necessary to create the final form. Do you remember if you’ve ever been disappointed by the final result? Did you ever wonder if in the end the building was worth all the effort spent?

No, I’ve never been disappointed with any work of Zaha’s. They are always so extreme as a moment of life, as a spatial experience. To see these buildings being constructed, being brought step-by-step from drawing and models into life has been a fascinating experience every single time. It’s like watching a child grow up and being constantly fascinated by how it’s going to turn out.

Having seen so many of her buildings come to life, as you say, which topics or motifs seem to you to be reccurring ones, like a well-known, reoccurring melody which maybe floats through her buildings subconsciously?

I see a strong sense of freedom in her buildings. This sense of endless space and the constant pushing forward of building technology. They are not places to meditate, to sit and think in quietness. They are places to fly. Even in Baku, in front of this enormous building, you don’t feel small but free and human and powerful; you don’t feel oppressed. Zaha’s buildings give you a sense of what we can achieve together and that we can push boundaries. In a way it’s a feeling of liberation. That is something that I really admire about her buildings.

- Interview by Florian Heilmeyer.

This interview was conducted for uncube magazine issue No. 37: Zaha.

Hélène Binet (*1959 in Sorengo, Switzerland) currently lives in London. She studied photography at the Istituto Europeo di Design in Rome and started working as a photographer at the Grand Theatre de Geneva in Switzerland, before she moved to London and slowly made her way into architecture photography. She has remained an advocate of analogue photography and has worked exclusively on film right up until today. www.helenebinet.com