Without her as Director of Planning, Mies van der Rohe and Philip Johnson would never have built the Seagram Building for her father’s company. The veteran architect Phyllis Lambert came to the opening of the DOKU.ARTS Film festival in Berlin and spoke to Jeanette Kunsmann and Stephan Burkoff about Mies, the last 60 years of architecture history, the future of building and why dogma will have nothing to do with it.

Ms Lambert in 2014 you received the Golden Lion for your lifetime achievements, not as an architect, but as an “advocate for a demanding architectural culture”, as Rem Koolhaas put it. What makes a good building?

You know, we all live in buildings. But if the players involved don't see architecture as a cultural force then you don't have architecture, you have commerce. For example: Mies van der Rohe made extraordinary architecture and developed his own language. If you are good at that, you talk prose, and if you are very good, you can be a poet.

You are an architect yourself. How did the cooperation with Mies influence your work?

Well, it gave me a point of view, a logical way of looking for and working with the facts and being inspired by the forces and the qualities that a city can have – because architecture is not just a building in a place. What is important with Mies is that you have a complex of buildings. The Seagram is not a building that you just go inside and up in the elevator. It has a plaza, and there is also this lower building behind. He created a place that is always opening and open. You get a sense of people living in the city. And you know: “less is more,” that always had a strong sense and logic to it for me. I was very lucky to have been trained really by him and how he approached his work.

What do you think about the current redesign of the Seagram’s interior, especially the legendary Four Seasons?

The man who owns the Seagram Building now is someone who likes to épater le bourgeois through the exaggerated “art” that he owns and puts in his buildings. Instead he should respect the quality and the history of great art and architecture, and realise what he has do, what it takes, to keep it wonderful. But he actually wanted to change parts of the Four Seasons restaurant: These two great rooms are connected by a corridor, which we always called the Picasso Alley. There was a wonderful Picasso there, a curtain from the ballet Le Tricorne. He said “I have to get rid of that – it is a rag”. But the Four Seasons is landmarked, it is protected. Together with many who care about great art and architecture, I fought so that he can't change it or the basic elements.

But he can certainly change the spirit of the place by introducing a go-go atmosphere into to a great elegant place where you can really talk … it is one of those wonderful places where the tables are far enough apart. I suppose he could put more tables in – there’s nothing to stop him from doing that.

It's been almost 60 years since the Seagram Building was completed. How has architecture changed after modernity and postmodernity in your opinion?

You know Mies wanted to show the people what to do, and he did. But the problem is they never understood the ideas behind what he was doing. So they made these copies – buildings with something a little bit like the Seagram-skin, but without any of the quality, without any sense of proportion, without a sense of the times we were living in.

Then postmodernity was a reaction. But it did not have the fun and interest that Dadaism had in the 1920s – that was wonderful! Nowadays, all are concerned with the materiality, of working with glass, working with concrete, working with steel – all of that is being reviewed and developed in a very interesting way. And look at the forms! Look at what Rem Koolhaas has done, for example, with those very same elements. The very serious problems of the environment world-wide as well the possibilities of design and fabrication the computer allows are changing the way we intervene in the built and natural worlds.

As a founder of the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA), you are involved for the perception of architecture as well. Why do you think contemporary architecture is so often misunderstood?

Contemporary anything is usually misunderstood – if it is good; if it pushes the boundaries! The same is true with literature and very much so with music. Theatre and film have enough common interests for people to get part of it, but this is not so in music, architecture or painting. It takes a while for people to get used to it. If people work within these fields, they do have a sense of background and history. But if they don't see that as a way of creating new thoughts and developing thought, then it takes some time.

It seems that throughout your life you’ve been enthusiastic about many different types of architecture and architects – you fought to commission Mies van de Rohe for the Seagram Building, but you chose a rather postmodern architect (Peter Rose) for the CCA in Montreal. You were also passionate about the documentation of historic architecture and the preservation of heritage, especially in Montreal. It seems you are a modernist, a classicist, a preservationist – do you actually see this as a contradiction?

No, I don't see any contradiction at all. It is all architecture. When you put a new building into the city you are relating to the buildings that are there. They all go together, we are working in a city and not working in isolation. It was essential for a great modern building to be established in New York in the 1950s, it was similarly essential to stop demolition of the historical fabric of Montreal in the 1970s and to reinforce it.

So, there is no room for dogma in architecture or city planning?

Yes, and landscape architecture too!

You actually didn't build much yourself. Why not?

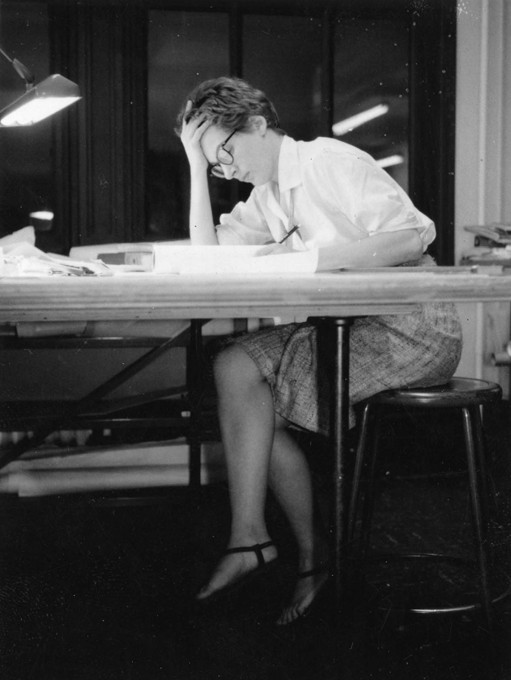

I had broad interests as you know. I was very interested in the history of architecture. I learned that by collecting drawings from the sixteenth century onwards. I had all these interests; I was interested in photography: I used the camera as a kind of notebook.

There had been inappropriate planning in cities, buildings being destroyed and the whole quality of the urban fabric was being trashed. Because people have no respect for architecture, they don´t understand it, they don´t understand buildings, they have no vocabulary for it. And I think people need to know this. So, when I founded the CCA it was always as a public concern, for people to be able to understand the city and to want to make it better. I felt I could contribute best in this way.

You say architecture has its own language and sometimes it is so avant-garde that people need time to understand it. But architecture today seems to want to be understood by everybody. Do you think it will find its own language again?

Sure, it will. But you know, you have periods of great changes in perception: about humankind, man and space. Like the Renaissance, which was a time of fundamental change. Industrialisation of course brought huge change, and with it came changes in bureaucratisation, because the more people you have, the more regulations you need. Some architects despair, but there is always a way of doing something wonderful.

You were born in 1927 and your life was grounded in a quite conventional lifestyle: in a patriarchal family with a self-determined existence. What would you like to say to women that are dissatisfied with their position in architecture today?

Yes, but I was lucky because I came from a family where, even though we were somewhat conventional in term of social mores, my father was a self-made man and so he had this great driving force. I had the great advantage of having him as an example. I also had the great advantage of a good education because we could afford it.

But the world has changed enormously over the last half century. When I went to architecture school in the late 1950s, early ‘60s – there were maybe two other women in the whole school. Now, 40-60 per cent of the students are women. The roles have changed enormously.

I think it is just the same for women as for men. You have to see something bigger than yourself, you have to see far beyond yourself and yourself in relation to the concepts of the time and to the people – you have to live with the scientific and moral changes of the times.

Which anecdote about working with Mies van der Rohe and Philip Johnson have you kept to yourself until now?

Mies and my father (Samuel Bronfman) had respect for one another from the first moment they met. Mies was not very comfortable with English, my father spoke no German and my mother (Saidye Rosner Bronfman) spoke some German. She was there, when we all had lunch together at their apartment. Mies had made a big model of the first, maybe five, stories of the Seagram Building to study the plaza level. My father had made one stipulation: he didn't want a building on piloti. When he looked at the model he said: "Mies, I thought I said I didn't want any stilts!" And Mies answered: “Yes, but come and see how wonderful it looks from over here, Mr. Bronfman".

– Stephan Burkoff and Jeanette Kunsmann are the editors-in-chief of uncube’s German sister publications designlines.de and baunetz.de respectively.