This week sees the opening of Wohnungsfrage (“The Housing Question”) at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin, an exhibition that sees four international architecture practices paired with social, bottom-up initiatives currently active in Berlin – Atelier Bow Wow/Kolabs, the Realism Working Group/Dogma, Estudio Teddy Cruz + Forman/Kotti & Co and Assemble/Stille Straße 10 – to see if, through collaboration, they can come up with workable solutions for the housing crisis currently affecting the German capital – and so many other cities.

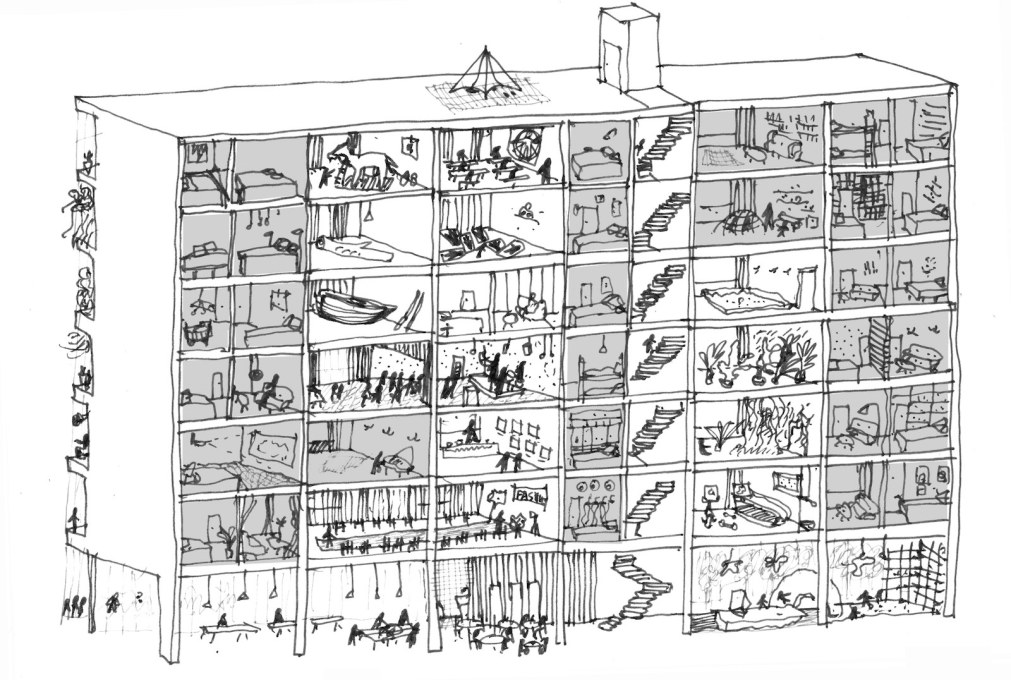

2015 Turner-prize nominated London architecture collective Assemble’s contribution takes the form of a proposal for experimental co-build housing designed in collaboration with a group who are perhaps Berlin’s oldest squatters: elderly residents who occupied their social centre, Stille Straße 10 in Berlin’s Pankow district, when it was threatened with closure. A model of the housing concept appears in the exhibition and ahead of its opening, architecture writer and researcher Diana Ibáñez López spoke with Assemble's Maria Lisogorskaya for uncube. Their conversation explores the collaborative vision that was built up – and what all this redefinition could really mean for re-empowering people when it comes to their options for urban housing.

How did you kick off the Wohnungsfrage research?

We gave a presentation at the Stille Straße community centre and drank apple juice together. Then we visited their homes as a way of getting to know them – and of beginning to ask questions that could guide the project. For us it’s been a really interesting experience. When we got the brief we thought it would be a project about designing co-housing for the elderly, or something like that. Then, listening to the Stille Straße group, that all changed. Old people are just people, with some more able than others to do things; elderly housing is not just about handrail design, it’s about how they stay part of a diverse community.

A lot of the Stille Straße group live alone, in apartments that used to be occupied by more people. But they don’t want to move out because of the harsh realities of the rental market.

So, in a way, your design takes on issues the institutional care system increasingly neglects…

Yes! Living alone is a real issue. It’s an obvious thing to say – but how you deal with that through architecture is less obvious. One of the challenges our 1:1 model addresses is how a living space changes as you grow older, and how throughout you can remain an active member of the community.

An anecdote in the exhibition publication describes how the Stille Straße group summarised your design as “an achievable utopia”. Is your housing model deliberately utopic?

The project is very theoretical; it is about building up an idea through architecture. Our idea is that co-housing can take shape almost anywhere: in dense infill sites or new-build wastelands, as cheaply and efficiently as possible. In that sense it is definitely utopic because it doesn’t have an actual site, an actual client or even a timescale.

Was it odd to design for an abstract, ideal “client”, yet at the same time following the advice of a very real, driven and site-specific collective?

In the beginning the Stille Straße group, who are still fighting to save their social centre, very much saw themselves as the client; they were confused as to why the project was about housing, and asked why we had been paired up. But as the project took shape it became clear it was about learning from their experience. They’re our collaborator rather than our client.

As part of the collaboration, the Stille Straße group visited Assemble in London. How was that?

It was funny. They kind of loved it. They were quite shocked by English houses. In Berlin they have high ceilings and lots of space, whereas in London most people live in tiny rooms. But they liked the atmosphere at Sugarhouse Studios and the fact that we were all making stuff.

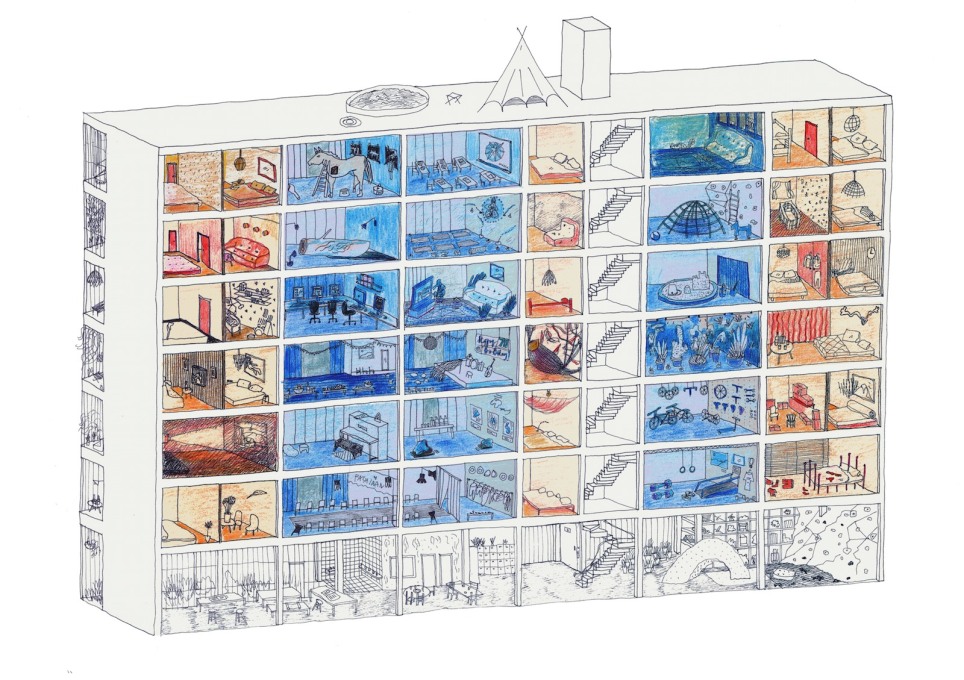

We also learnt a lot about how their collective got together. It is an interesting story. Their social centre was originally organised by a charity, to help those in East Berlin forced to become pensioners early when they lost their jobs with the fall of the Wall. Then funding ran out and they had to survive alone – that’s when the group began self-organising. When they squatted the community centre, the act of squatting itself was a way of coming together. The squat scene and the press rallied round. That’s the bit they really enjoyed and keep coming back to, because they felt they were part of an active society. So we are trying to build an infrastructure of getting to know each other into the block. The moment of moving in is a gradual and very important creative process.

It sounds like designing an infrastructure intended for the unexpected, for surprise...

Exactly. I hadn’t thought of it like that. They also talked a lot about sweat equity, and the socialist housing programmes of their time in which they invested time as a way of purchasing their homes – that was inspirational.

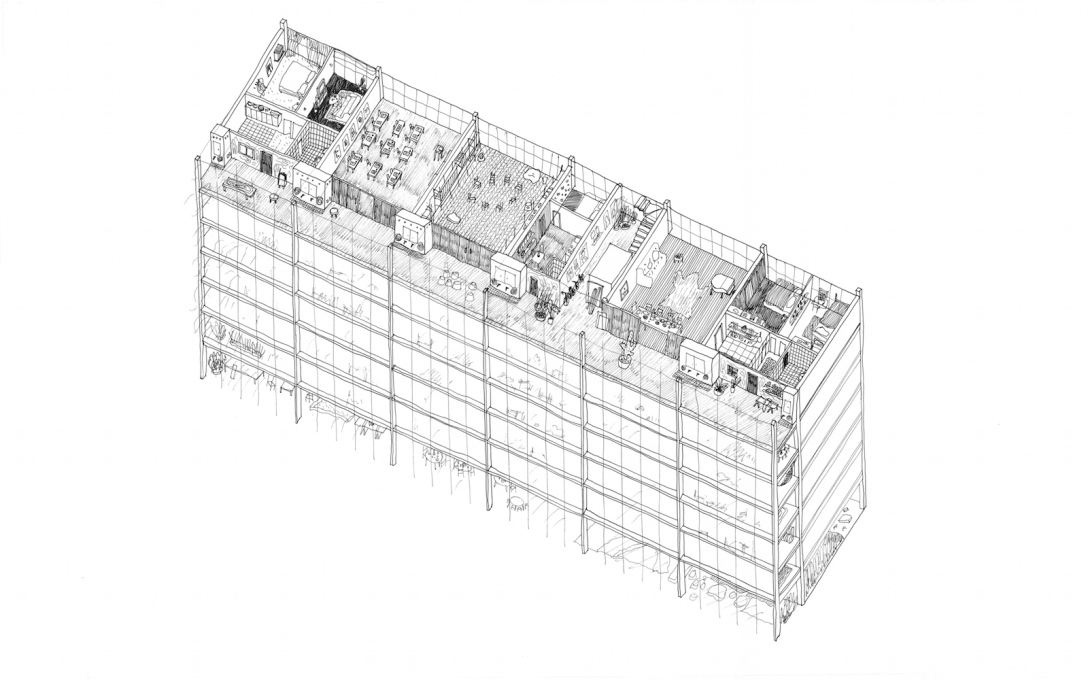

So the block, despite not having a site, is inspired by East Berlin, and more specifically by the historical context that led to the occupation of the Stille Straße social centre… How much has a Soviet aesthetic influenced your concrete-frame “infrastructure”?

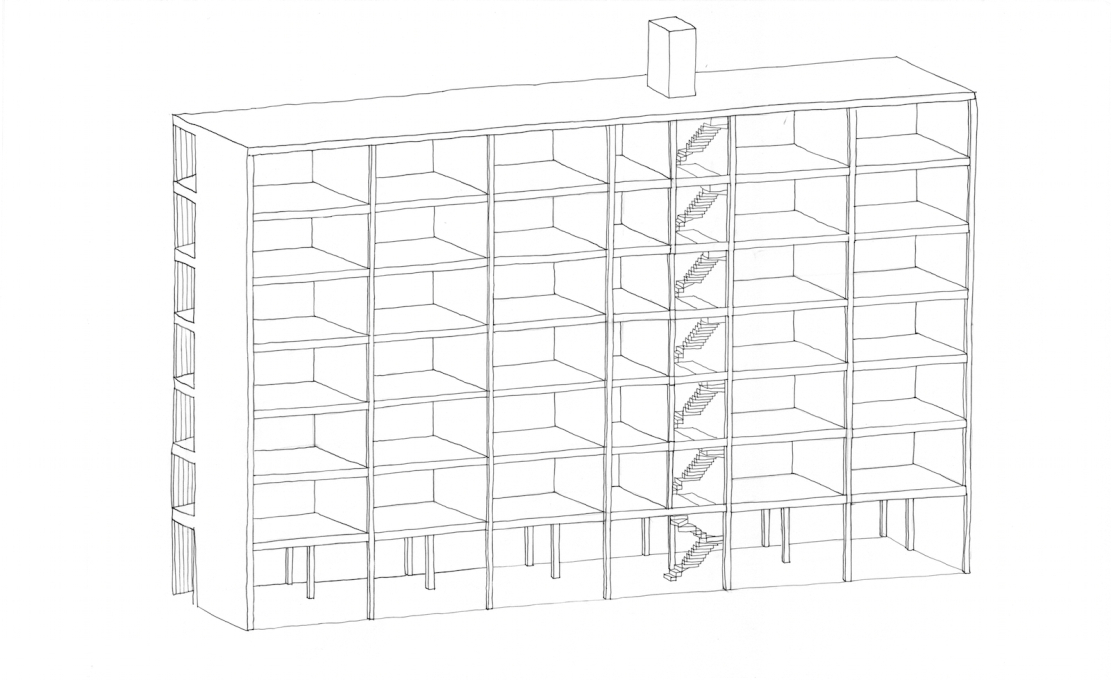

The form did come from ideas of simplicity, generosity and cheapness which we’ve partly learnt from that era. There are elements that reference the plattenbau (prefab block), but we also looked to contemporary concrete construction and the resemblance comes in part from the lack of site, and the abstractness of it. Also, the roughness and lack of preciousness of the materials is important, because the detail comes in at a smaller scale, built by the community.

Zooming into the detail then, tell me more about the 1:1 model on show at the exhibition.

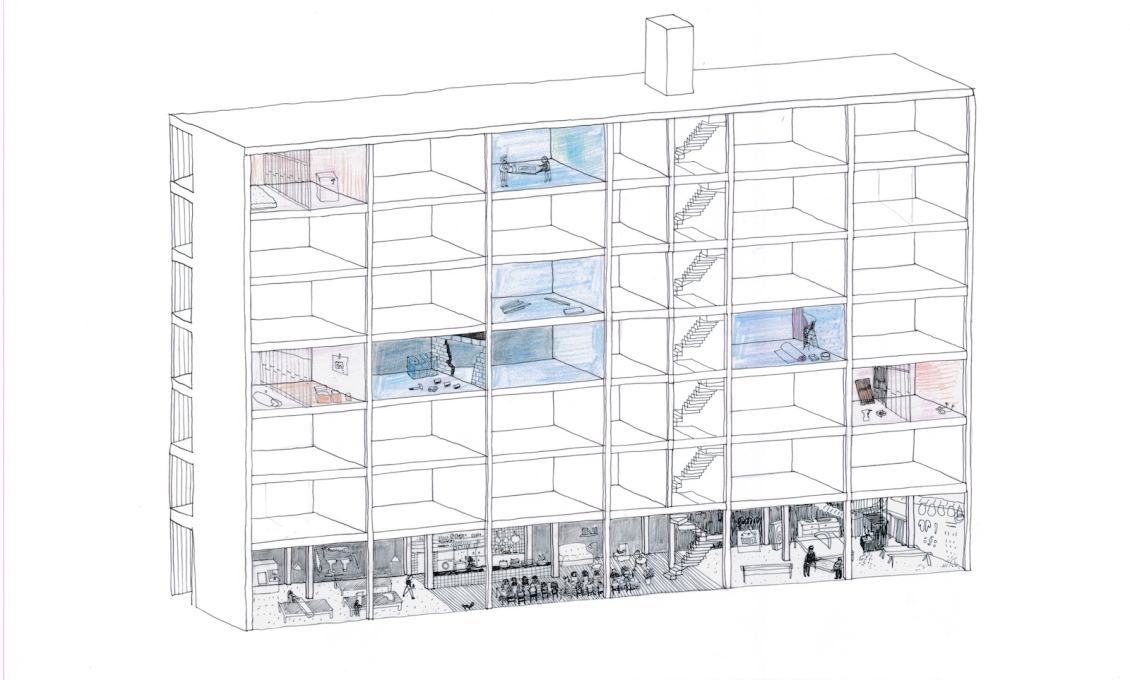

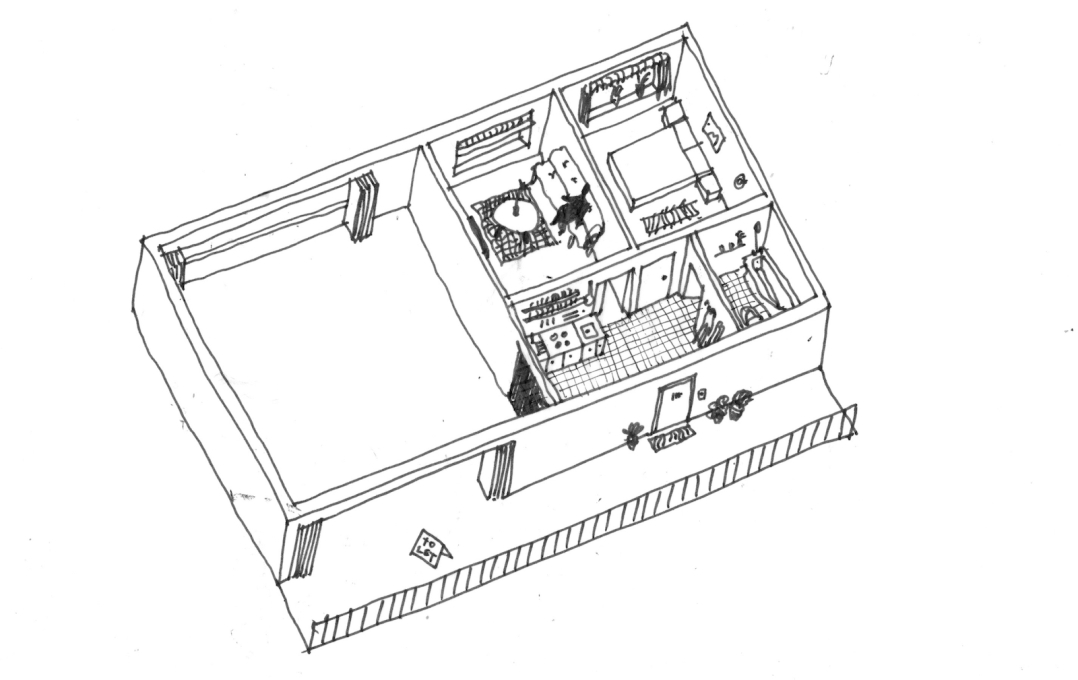

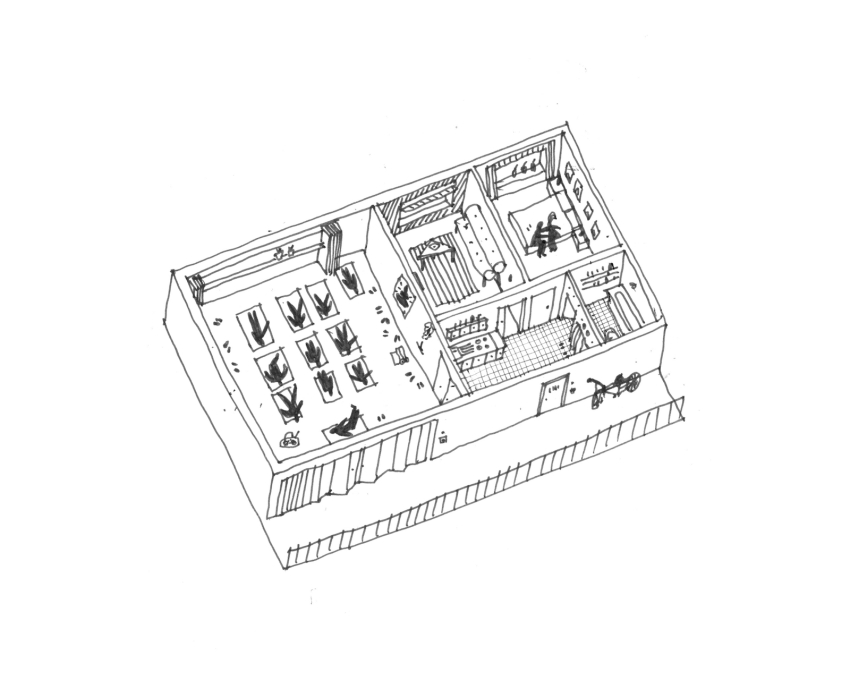

The idea is that a cooperative of sorts builds the frame. Within it two substructures alternate: “house” and “garage” units, which we’ve called ‘A’ and ‘B’. You would buy A but would rent B, expanding and shrinking your apartment as the family grows or shrinks. B is key. You can fully open it to the collective corridor, making it very different from a dwelling space entered through a single door. We’ve come up with a composite German name for it: teilwohnung. Teil means part, but it can also mean to take part, or a piece of something. It has lots of possible meanings that relate to the model and the co-building community ideal.

Type B units can be either an extension of the home or shared communal spaces. Could these potentially be as public as the communal centre that will replace the workshop on the ground floor after co-building slows down? Are there different levels of publicness throughout the block?

It’s a range in between. The ground floor could be very public, like a café, but type Bs are a lot more about the community. Of course, an inhabitant could use it for something like a yoga class which is open to the public, but it’s not on the street, it isn’t really intended to be open to the whole city.

Have you projected how a tenant might use the space in your model?

The exhibition shows the space as you would receive it from the building co-op, although modelled in wood rather than concrete. We just provide the basics, so you could make two rooms out of it, or a bedroom and a living room, but nothing is defined yet. Inhabitation is left to visitors’ imagination, just as it would be left to the tenants’.

I love your concept of creating infrastructure for community activity, and that at first, that activity is what completes the interior of block, so that the project is very much built on 1:1 relationships between people. You start with a ready-made frame, but there is no ready-made community.

That’s a beautiful way of putting it, or maybe post-rationalising it.

Might the Stille Straße squat the 1:1 model for the duration of the show?

We did talk about it, but somehow a plan didn't materialise. Perhaps they’ll still be inspired!

– Diana Ibáñez López is a researcher writing and working at the intersection of urbanism and material culture. She is based in London and sometimes Holland, where she is associate editor at The Why Factory.

Wohnungsfrage

From October 23 until December 14, 2015.

Haus der Kulturen der Welt

John-Foster-Dulles-Allee 10

10557 Berlin

Germany

Further reading: take a look at uncube’s Urban Commons issue!