feld72, a Vienna-based architecture practice, have recently completed a social housing complex in the village of Eppan in South Tyrol, Italy. Sensitive to the village’s historic fabric and to the spectacular surrounding landscape in the foothills of the Dolomites, the new development does not try to stand out, but is instead designed to mediate the relationship between residents, the existing village and the views. Sara Faezypour interviewed feld72’s Peter Zoderer and Michael Obrist for uncube on how the project came about and the complexities of incorporating the new development into the village’s delicate ecostructure.

What was the background to the project and its brief? Was it an open competition or were you invited to participate?

PZ: In 2012, the local municipality organised a competition for a single residential building with 23 units for social housing. We were one of three architecture practices asked to propose a scheme for this, and ours was selected.

What do you think was distinctive about your approach that won you the commission? How did you go about developing your design?

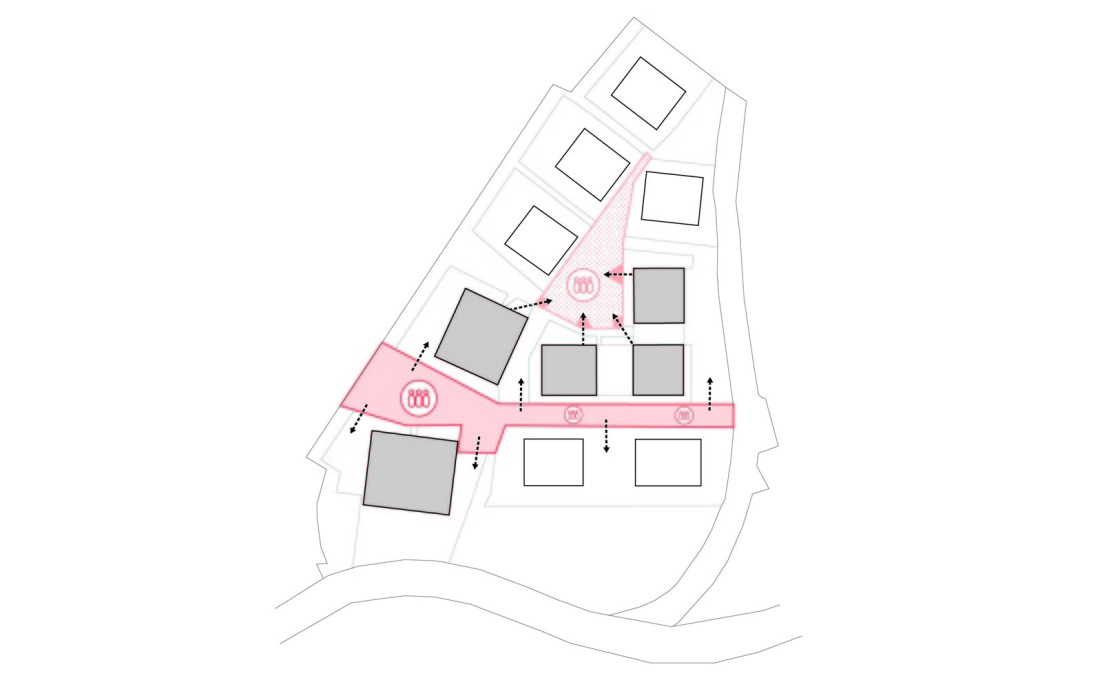

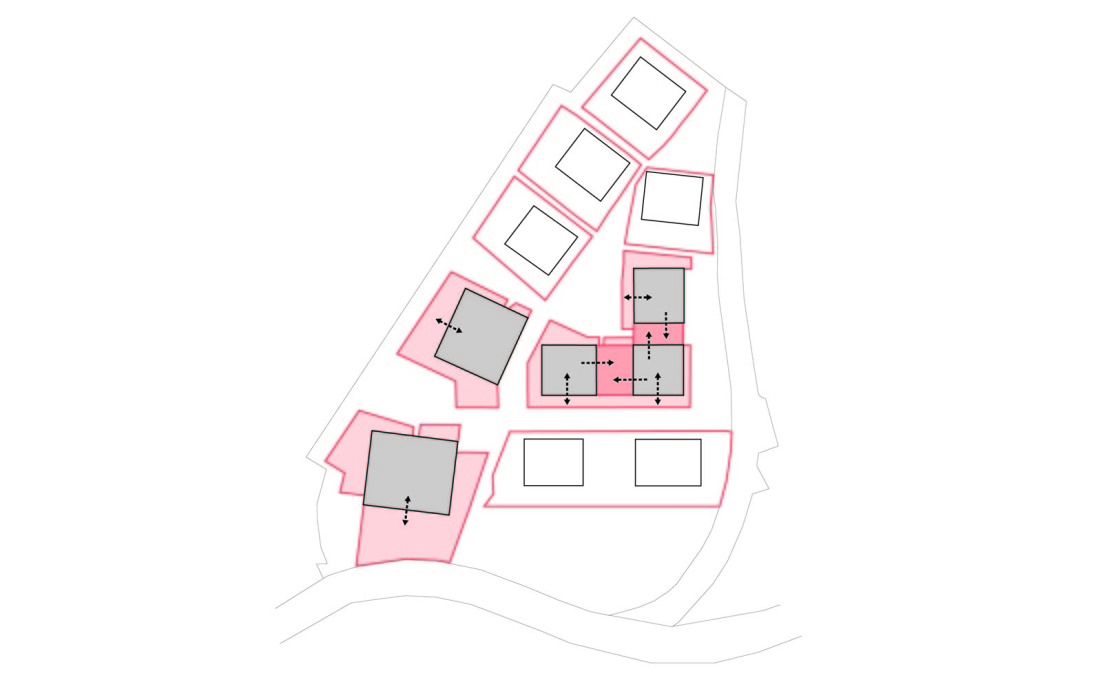

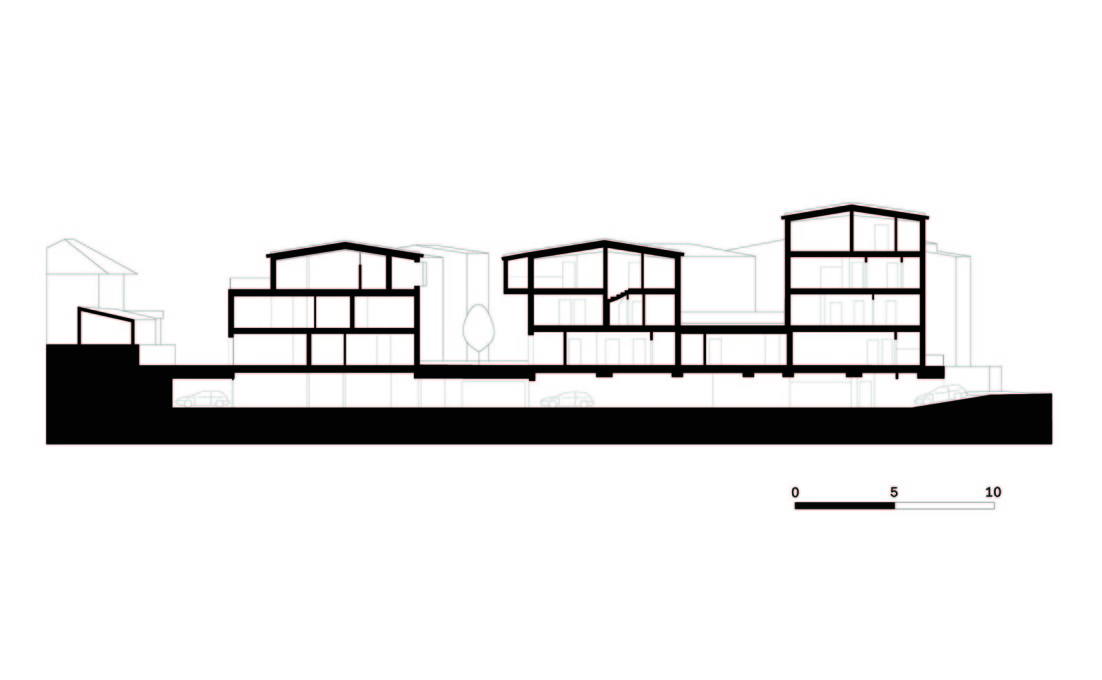

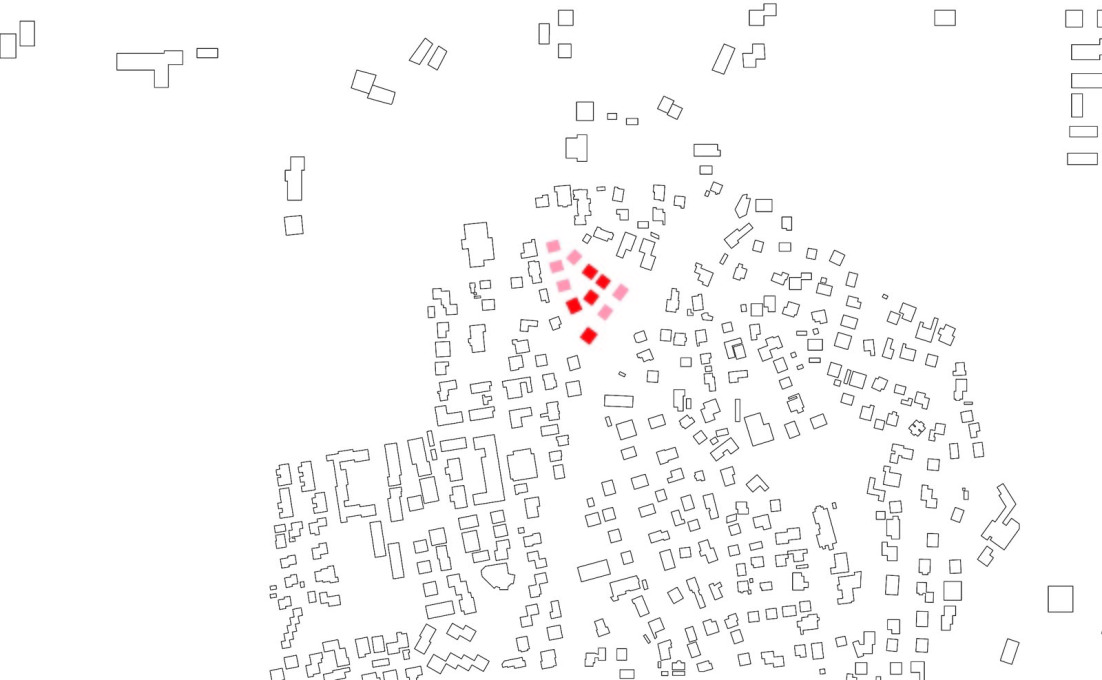

PZ: Our approach was not to come up with one or two buildings, but to try to follow the pattern of organically grown structures in Eppan village, in order to create diversity and variety in the scheme. The resulting houses are grouped around a green inner courtyard open to all like a village green or “common”, as it was once called. The houses are plain and simple in design, reticent in form and expression. As a response to the programme and topography we developed several different house typologies, which we then unified through the use of material and the repetition of certain formal elements.

The clients were two “Baugruppen” (associations of private owners), meaning the project was developed and driven by quite an intensive process of participation by the future inhabitants. It was difficult to convince them at the beginning that building together was not only economically advantageous but also a chance to build a community and neighbourhood. We had to struggle a lot to encourage them to get involved, but we believed that the collaborative process would ultimately end in a greater sense of shared identification with the project.

What is the context of the village of Eppan: its climate, surroundings and history?

MO: Eppan is situated in the southern part of South Tyrol and has a very mild, almost Mediterranean climate. Because of its strategic position, there is a very rich history of castle-building in the area around it – in fact, it has the highest density of castles in Europe. These castles and manor houses were mostly built from locally quarried porphyry stone and were an important point of reference for us in the project. In our scheme, the prefabricated concrete walls also borrow their colour from the surrounding rocks, so when seen from a distance, the settlement appears to be almost fading into the landscape. We spent a lot of time researching local materials and spatial qualities and tried to translate those elements into contemporary architecture.

The site is surrounded by an incredible landscape. How did you take advantage of this or react to it in your design?

MO: One of the most important elements of this housing project were obviously the views, these are breathtaking towards the Dolomite mountains. So it was crucial to create a scheme that would allow views towards those mountains from all the apartments – not just those in the “first row”. We wanted all the residents to enjoy the view.

What made it necessary to build such a volume of new residential units in such a small village at one time?

MO: Eppan is becoming a very attractive area to live in as it is very well connected to the city of Bolzano whilst being surrounded by this amazing landscape. However, just 7 percent of the South Tyrol province has a suitable surface for construction. In the 70s the local administration passed very rigorous laws governing the development of settlements, so it is nearly impossible to build a free-standing single family house outside of the pre-existing borders of a town in this area. The municipality of each town decides on the specific plots for their expansion so the landscape is preserved. As a result the villages and towns are compact and relatively high-density entities within this natural context.

Were there any cultural values or building traditions that you took into account in the process of the design?

MO: South Tyrol is a border region with a lot of different cultural influences from the north and the south. It is a melting pot of architectural traditions and – as a result of the education of young architects in the region from Italy, Austria, Germany, Switzerland – also a point of encounter for different architectural discourses. This makes the region very special and unique in its response to contemporary architectural questions, such as how to deal with the impact of globalisation at a regional scale.

Although recently completed, the complex looks as if it belongs there, has been there for a while: perhaps due to your choice of material. Was it intentional to seem to reference back to earlier models of housing or is this just a superficial impression?

PZ: The buildings are self-evident, serene and representing nothing. They are just there. In this sense your impression is not superficial at all.

– Interview by Sara Faezypour, former editorial assistant at uncube, who has a BS in Architecture from Tehran University and an MA in History and Critical Thinking from the Architectural Association, London.

feld72 was founded in 2002 in Vienna. They have implemented numerous architectural, urban and artistic projects in Austria and internationally. Recent projects include the Regional Authorities Building in Krems, Austria (2011) and a Kindergarten in Montal, Italy (2013).