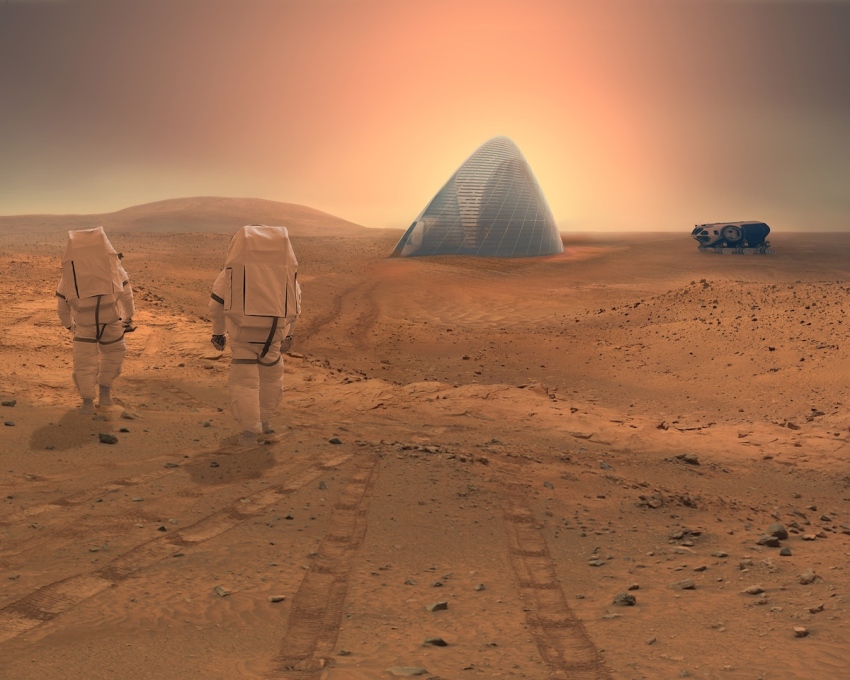

Most designs for habitats on other worlds envision astronauts living in grim bunkers, buried underground to shield their bodies from the punishing effects of solar radiation. Exiting via an airlock, they can venture outside, but only for brief excursions in pressurised spacesuits and rovers: an exciting but hardly aspirational lifestyle. Using existing technologies and scientific insights into Martian physics, a new collaboration between SEArch (Space Exploration Architecture) and Clouds AO (Clouds Architecture Office) hopes to change all that. Their Mars Ice House employs a locally-sourced material – ice – to create a sleek, human-focused habitat that would make living off-planet a little more bearable. Combining expansive views out over the Martian landscape and a unique garden space, the design recently won NASA’s 3D Printed Habitat Challenge, chosen from a shortlist of 30 submissions that counted Foster + Partners among them. Chris Hatherill accepted a mission from uncube to catch up with SEArch’s Kelsey Lents to find out more.

Can you tell us a bit more about how SEArch works?

SEArch is a group of five people who came together through academic ties, mostly from Columbia University and the space studio there. We’re all pretty passionate about space architecture so we formed SEArch to continue working together but as we all work full-time, we tend to meet and work in the evening. For the Mars Ice House we worked with Clouds AO, which made eight of us – all architects by training. From the start we would all meet to brainstorm and that really set the tone for the project. It wasn’t really a division of labour, more eight minds working together.

When did the idea of working with ice first emerge?

It actually came in pretty early on – the competition made clear that NASA had an interest in indigenous materials. We really love this idea: that when you start thinking about building on Mars you use materials that are already there as opposed to having to bring everything from Earth. It’s a more efficient and sustainable way to build. NASA now has a kind of credo: they “Follow the Water” across all kinds of missions. The idea is that water is the building block of life so wherever there is water – in theory – life in some form could exist. That was a really interesting concept to us: if they are already following the water then we should use it in the construction of our habitat.

And in the process you found the ice has some pretty good properties?

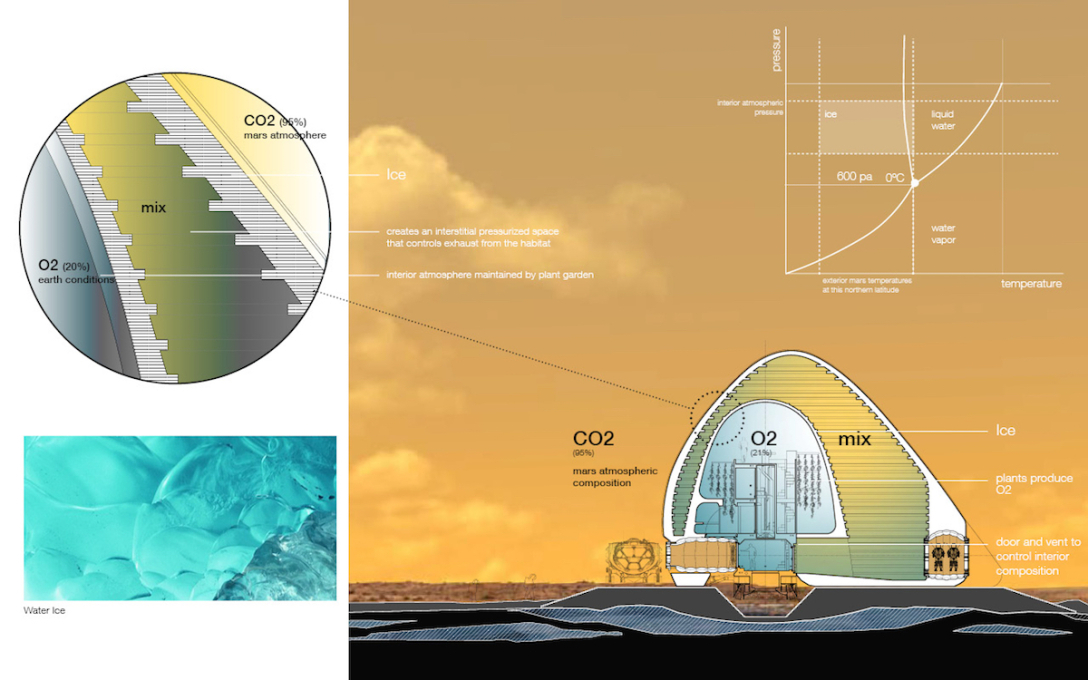

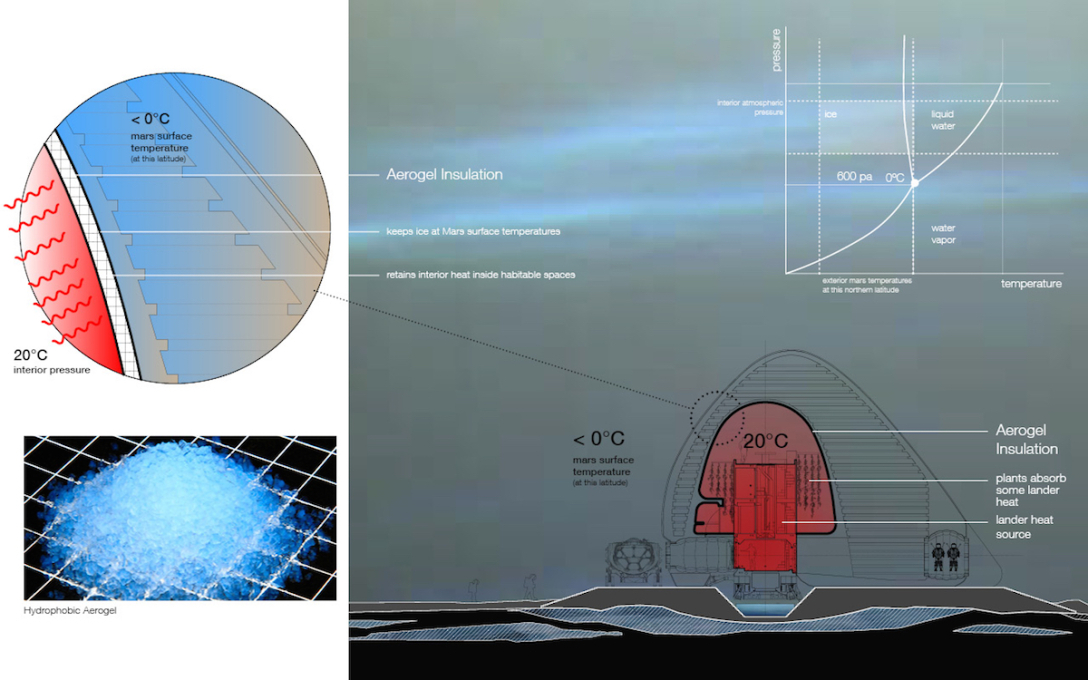

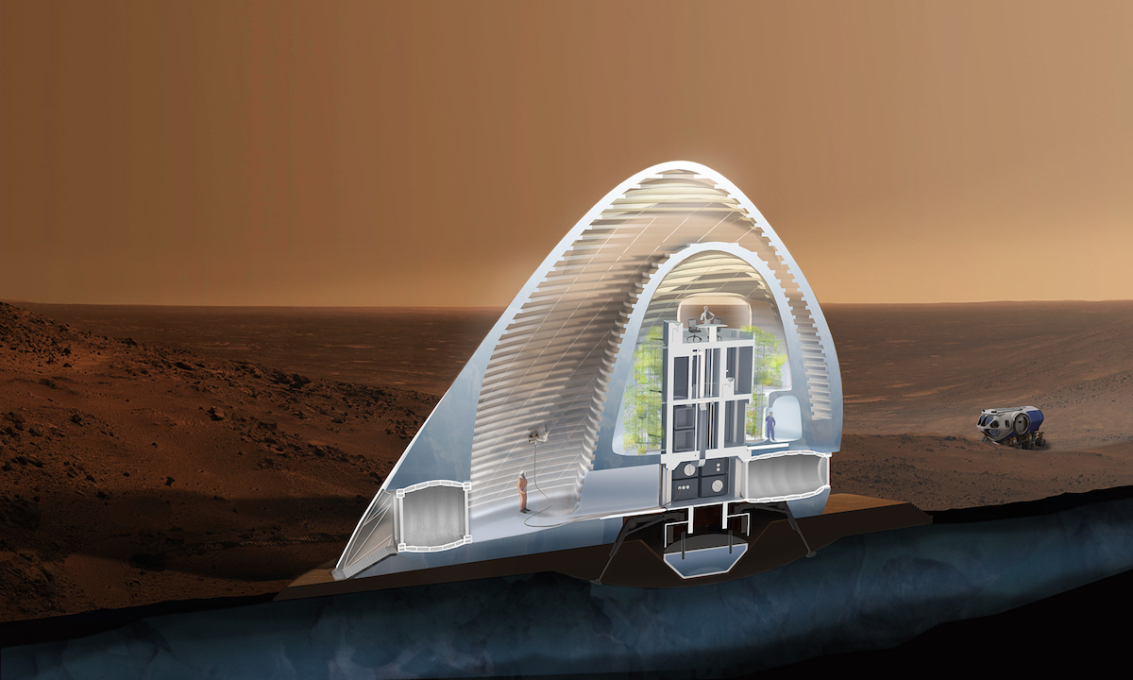

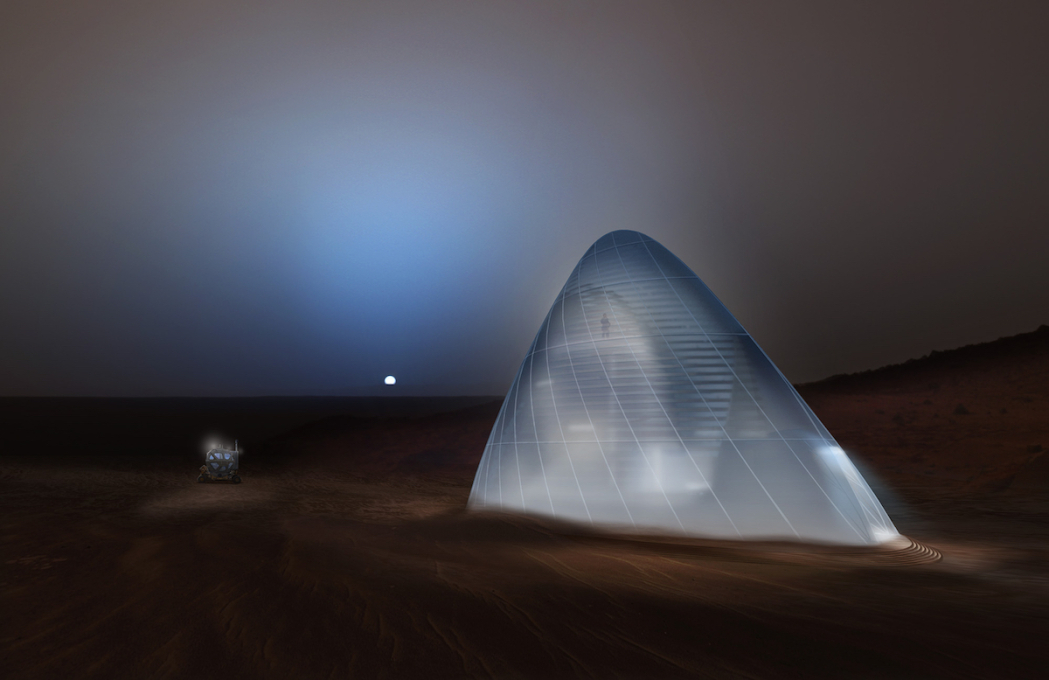

It’s one of the best radiation barriers out there. You can build something incredibly thin out of ice and it remains incredibly efficient at blocking radiation, yet at the same time it transmits light, so it not only protects humans but it also contributes to their mental wellbeing. For us, it was important that light played a factor in that. That was one of the main reasons we stayed away from building with Martian soil, with regolith.

Another reason, that I’d not heard before, is that Martian soil can be harmful to humans. Is that right?

Building with regolith has been talked about for a long time, but we found a couple of papers that talked about different materials that can be present in it. One of them is percholate, another is gypsum – both are potentially hazardous to humans. Ice has the ability to do everything that regolith can, but with less material. It’s more energy efficient as you don’t have to have the same thickness as regolith because it’s better at absorbing radiation. It also lets us build vertically, which was critical. We really wanted to create something that felt like a beacon in the Martian landscape. With ice, the structure is self-supporting – we didn’t need to build a scaffolding below it.

You consulted quite a wide range of scientists for the project. How did that come about?

Early in the process we brought in external consultants to advise us on some of the areas we weren’t as familiar with, like radiation specialists, geophysicists and structural engineers to have conversations with about the design as we developed it. We approached the habitat as architects, imagining it as a space where four people would live for some time, really considering the space and what it would feel like to be inside of it, as opposed to approaching it from a highly scientific or technical point of view. We didn’t want to lose sight of the fact we’re architects and designers – and that for us, the human comes first.

How would the Mars Ice House be set up?

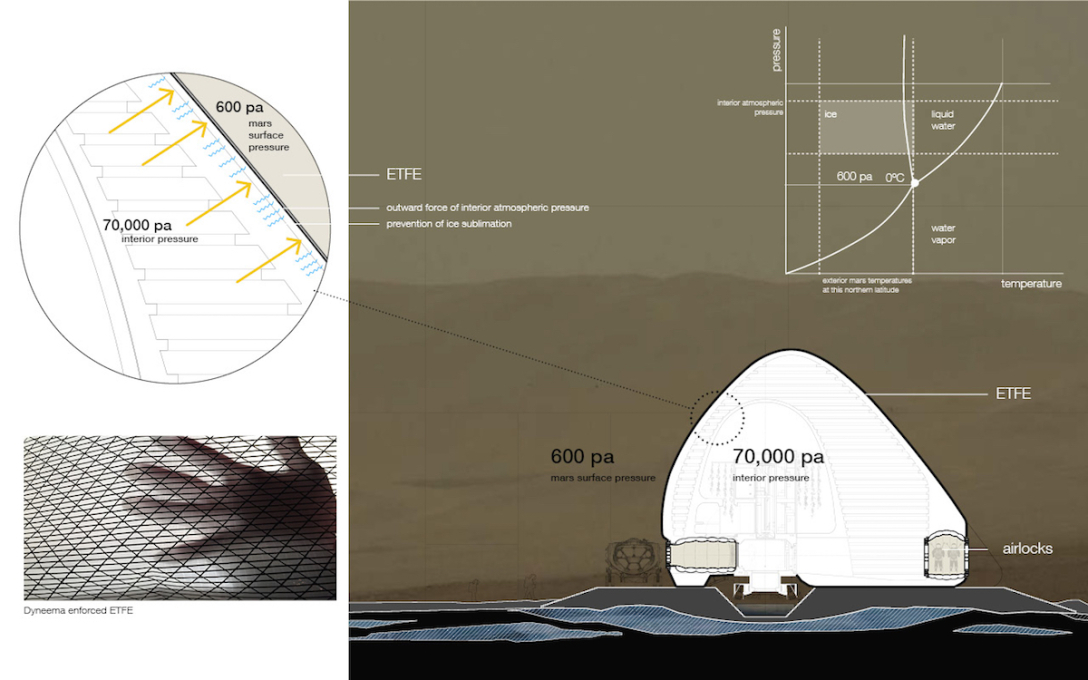

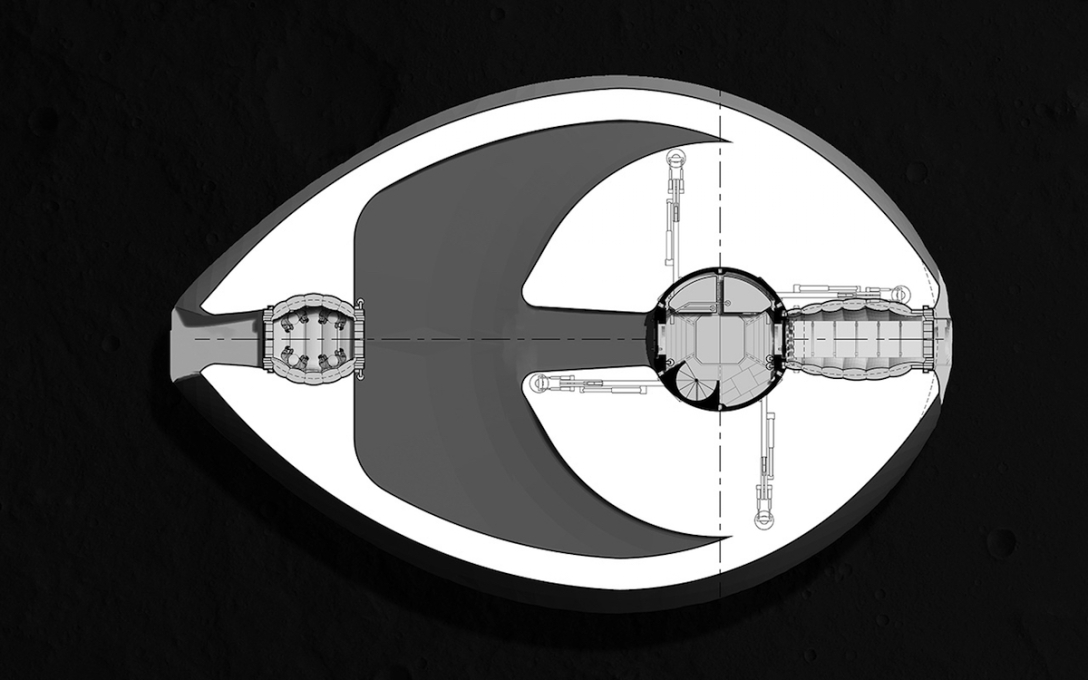

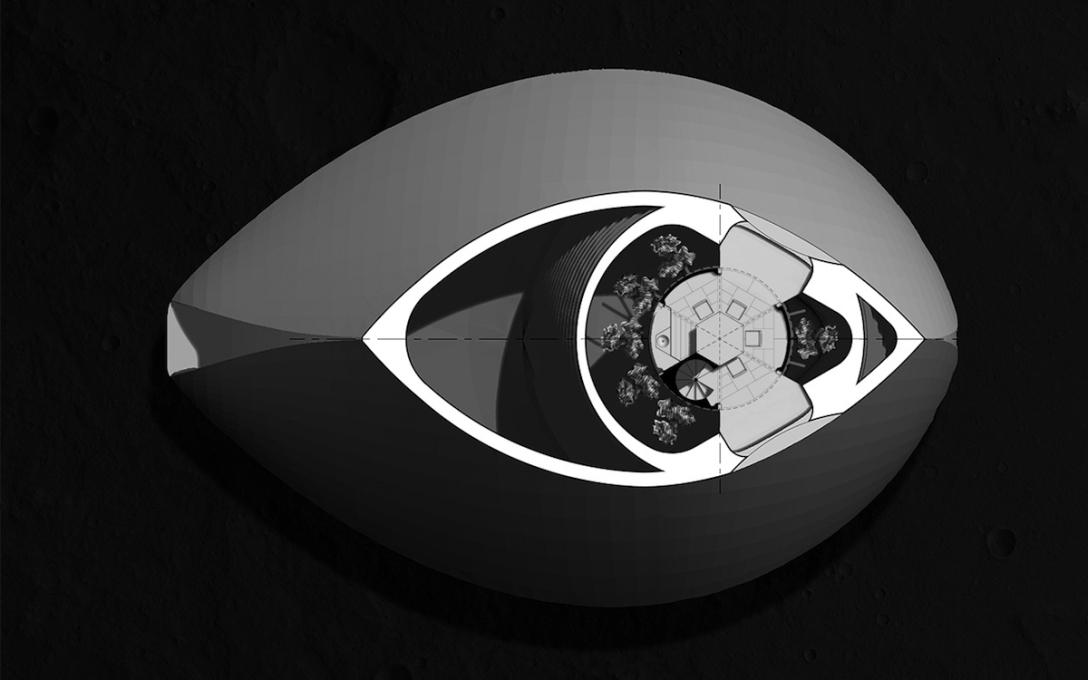

The idea is that you’d send a robotic crew ahead and humans would follow. So everything that is incorporated into the core of the design fits within the capsule size of the lander. That would land and carry with it the robots and an ETFE membrane – which is a transparent material that’s been tested in space before, and which would blow up, almost like a hot air balloon. This membrane and the ice then create a pressure barrier.

Where does the ice come from? How does it come to be 3D printed?

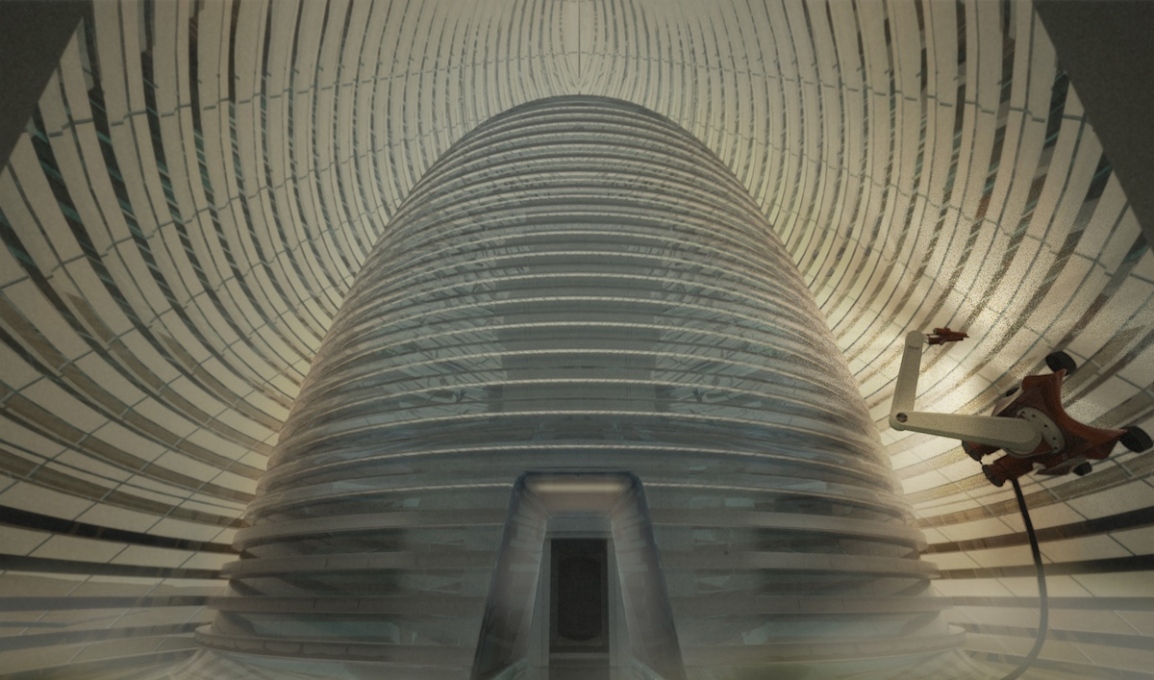

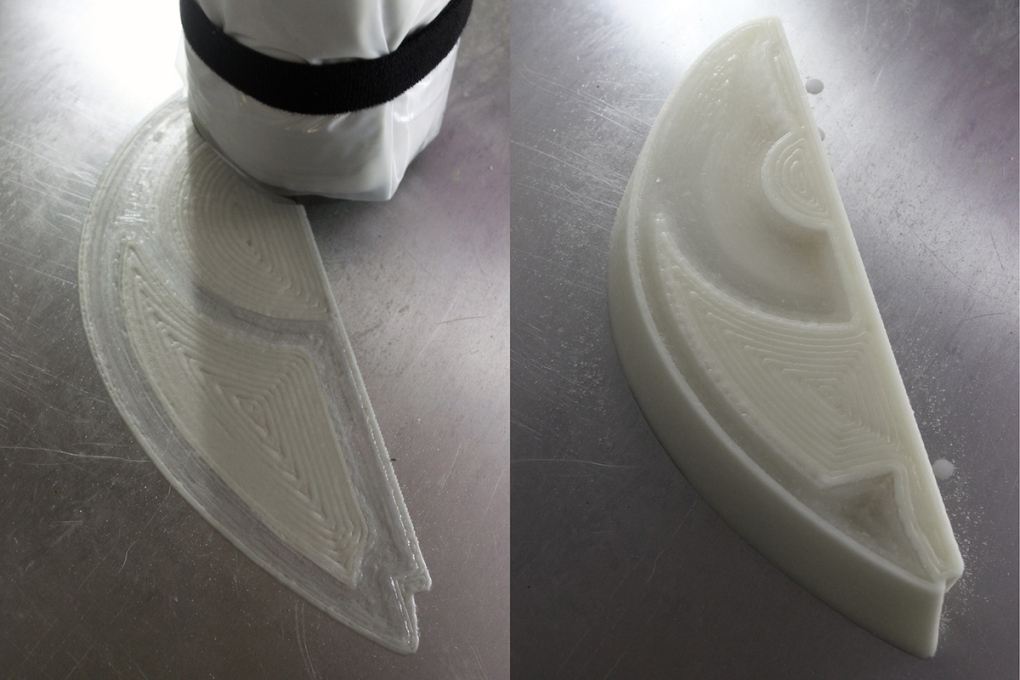

There’s quite a bit of subsurface ice on Mars and the site we’ve proposed landing at is in an area where the ice is not that deep down – it’s thought to be only 30cm beneath the surface. We have two types of robot, the first is a sintering – or 3D printing – robot, which would prepare a foundation using regolith to stabilise the lander. The second is a combination robot that both mines and prints the ice.

Because of the pressure and temperature conditions on Mars, whenever ice hits the atmosphere it sublimates: it turns directly from its solid state into a gas: water vapour. So our technique for 3D printing relies heavily upon the physics of state change: a simple solid to vapour process, as opposed to the need to create complex compounds for binding material, that’s typical for 3D printing. The idea is that the robot would mine the water as vapour and collect it in a vacuum bag. Then when it’s printed out from the robot’s nozzle it turns back into its solid state – ice. We can control this process because we’re controlling the pressure inside the habitat; creating a pressure differential which will keep it in its solid state.

So this process would leave a space ready and waiting for the crew upon their arrival?

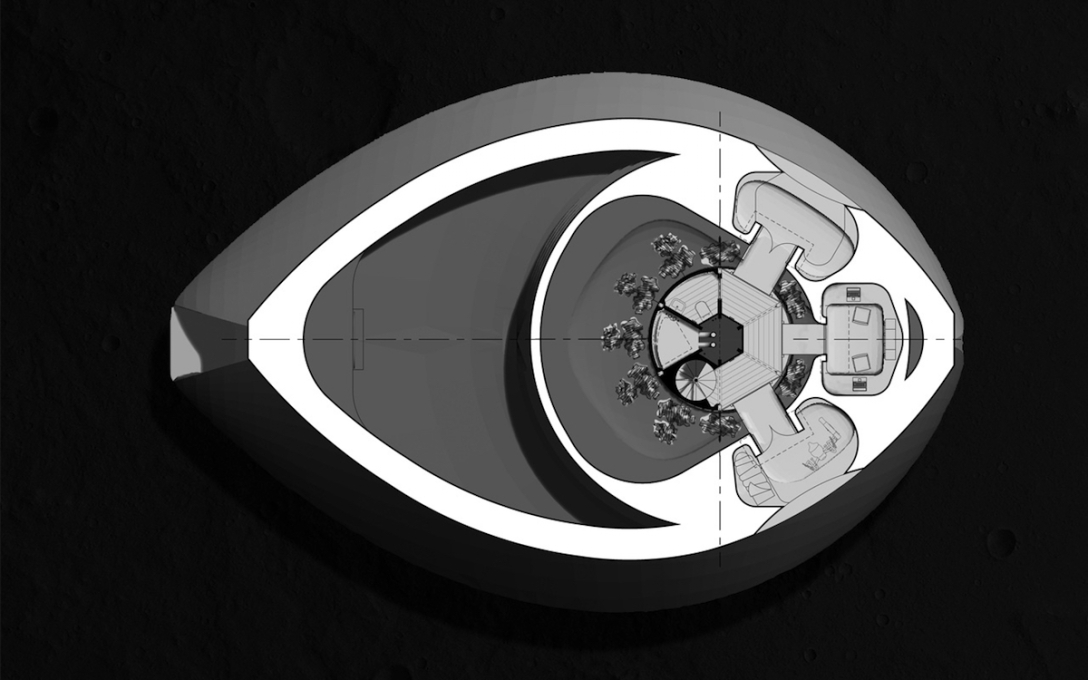

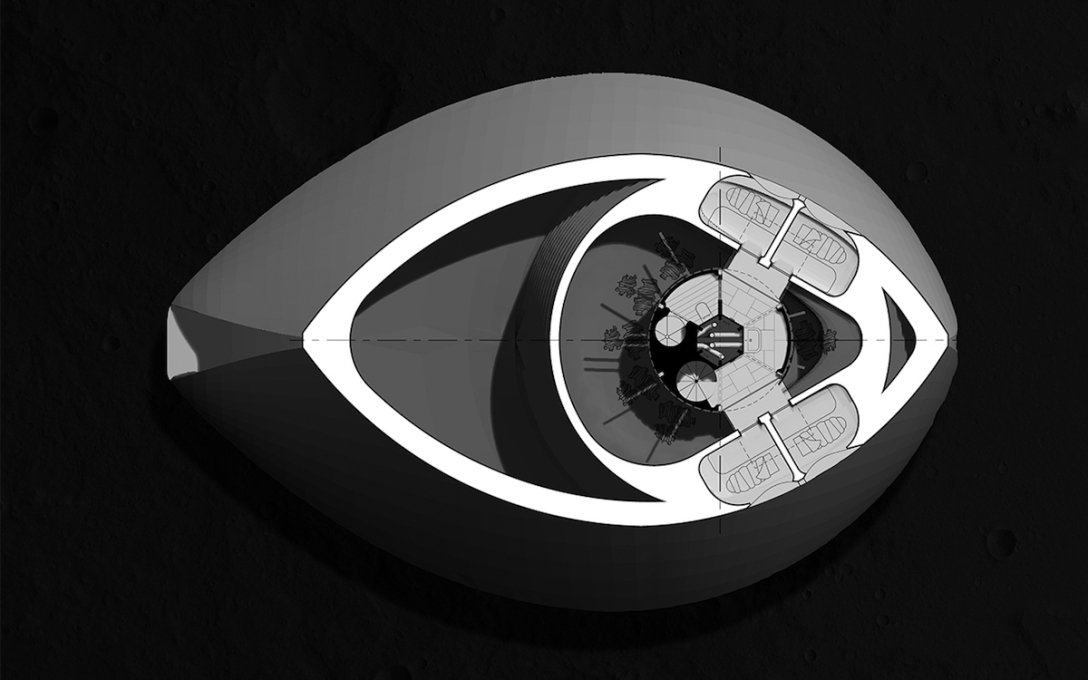

Yes – it means when the crew arrives they have a couple of different pockets of space they can inhabit, creating this concept of interior and exterior space that we have on earth, but that we’ve never had off-world before. You would still have to wear a helmet in the space, but because of the pressure you wouldn’t have to wear a pressure suit – it’s like a garden. There are some vertical planters in the space too; we see it almost like a front yard. The idea is to take all the hydroponic gardens and site them in there, instead of in some kind of separate self-enclosed machine. Instead of it feeling like a kind of science experiment, we really wanted it to feel more like it was part of the habitat.

How much of this is based on existing technology? Is it a Mars-specific concept?

The concept is quite innovative but we’re not inventing any materials – all of the components exist in some form. We talk about robots that can print vertically and climb walls – those robots exist. We talk about printing in ice – that has been tested. We really wanted to focus on how far we could push it, knowing what we know today. We’re starting on Mars but eventually you could be on a number of different worlds, so something like having water as a common factor throughout was really interesting to us. It has so many properties that make it a perfect building block for extraterrestrial construction. Mars is the next planet humans will reach, but there’s so much scope for further exploration out there. We feel that a scheme that’s translatable, using indigenous materials, has tremendous potential.

– Chris Hatherill is a freelance journalist and founder of cultural science agency super/collider.

spaceexplorationarchitecture.com

Further reading: boldly head into the architectural beyond with uncube issue no.19: Space.