The tendency to hide the reality of death from everyday life – both physically and symbolically – is probably even more pronounced today than ever before and is something that the design of architecture – from hospitals to crematoria – has been complicit in. George Kafka explores research that is looking to change this and proposing new civic infrastructures and spaces that celebrate, memorialise – and utilise – the processes of death.

“The greater the degree of mechanisation, the further does contact with death become banished from life.” Siegfried Gideon’s diagnosis of attitudes towards death mid-century rings as true today as it did in 1948. Ever since the Enlightenment and the development of the architectures of health and hygiene – sanatoriums, hospitals, abattoirs – we have undergone a physical removal from the processes of death. Spaces for death and the dead are siphoned off and corpses have become both spatially and psychologically distant; banished to isolated cemeteries where space is scarce and the cost of burial (both ecological and financial) is rising rapidly.

In the face of these unsustainable practices, researchers at both Columbia and Princeton Universities are proposing radical new solutions for death rituals and memorialisation that will bring mortality back into our lives and have the additional potential to reinvigorate the public spaces of our cities.

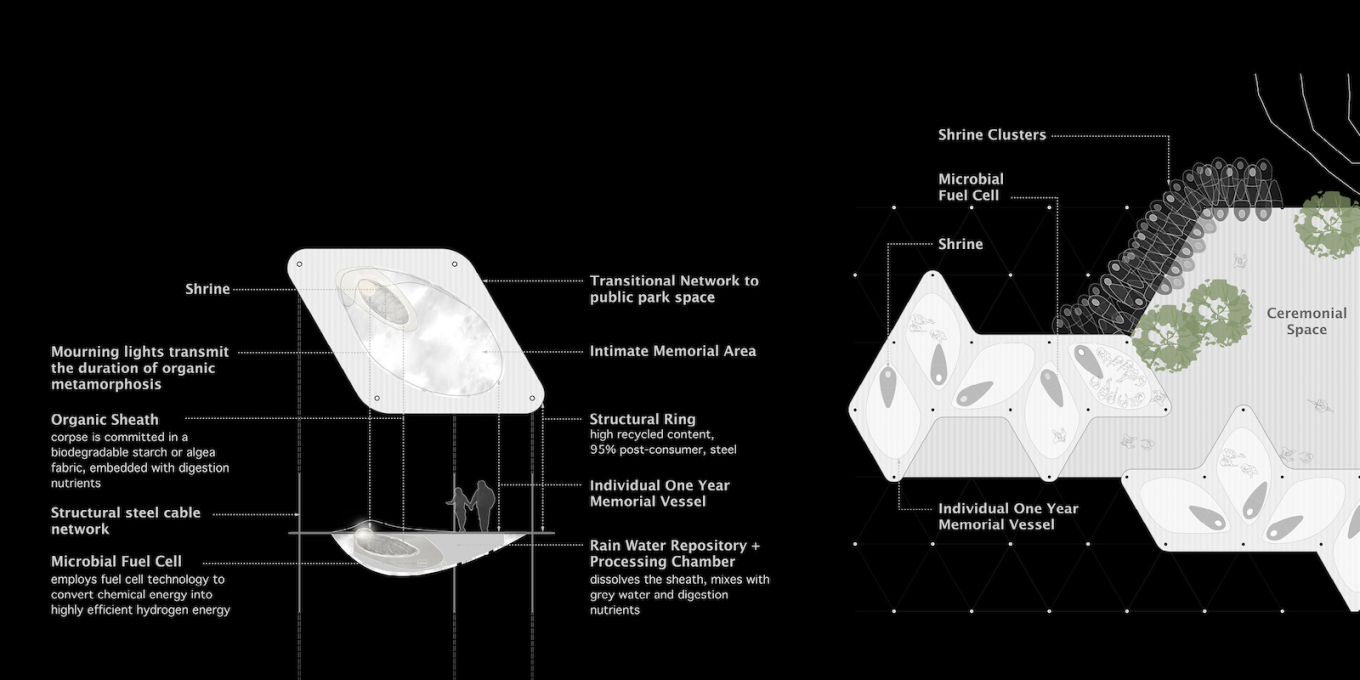

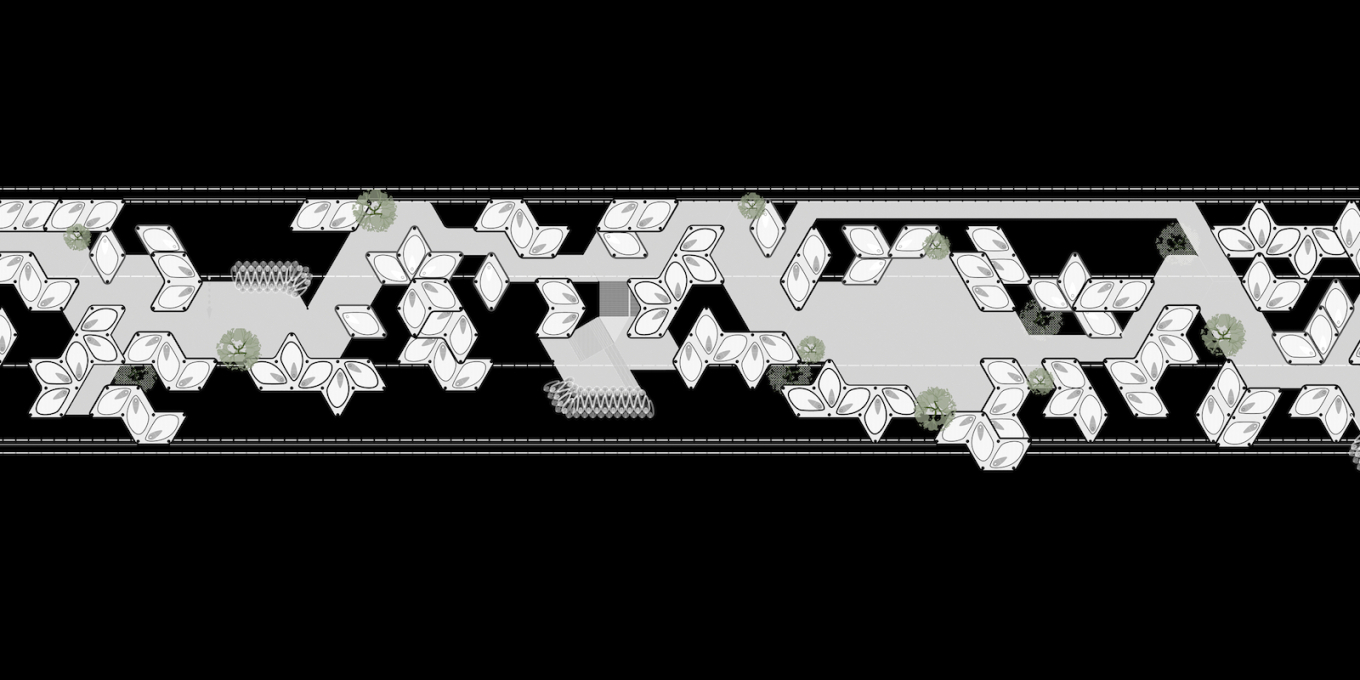

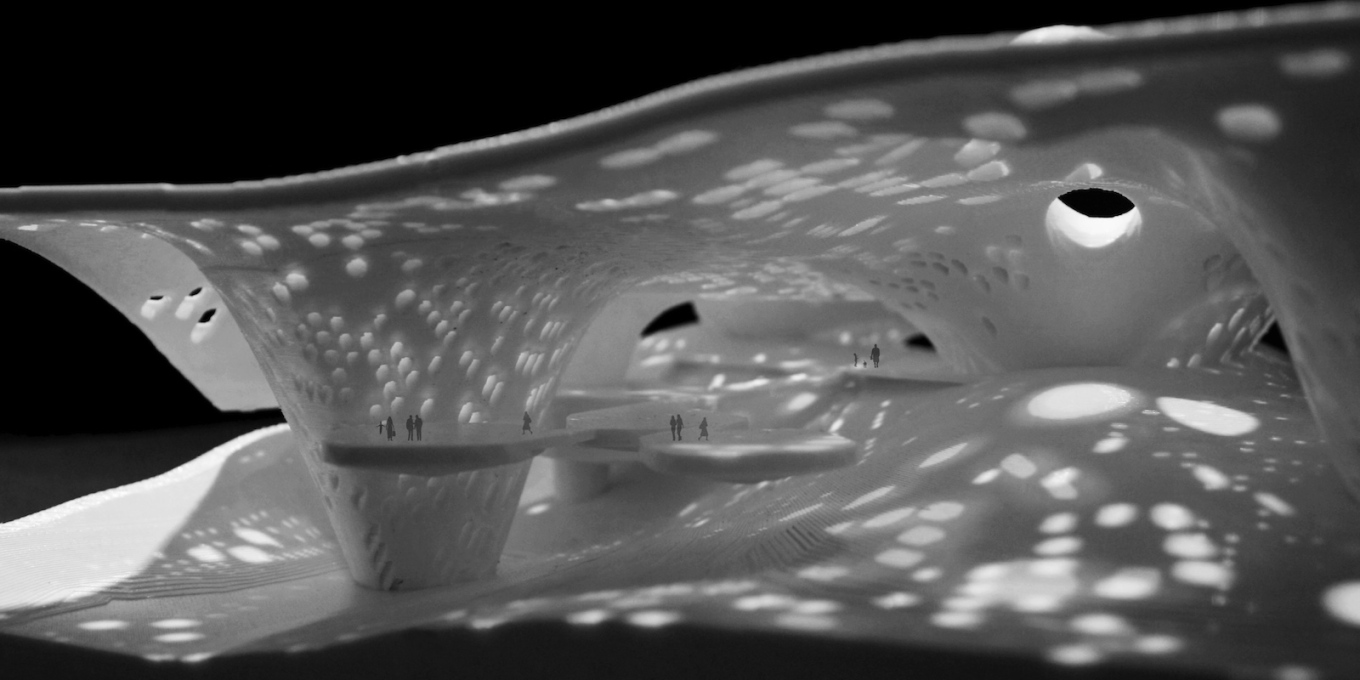

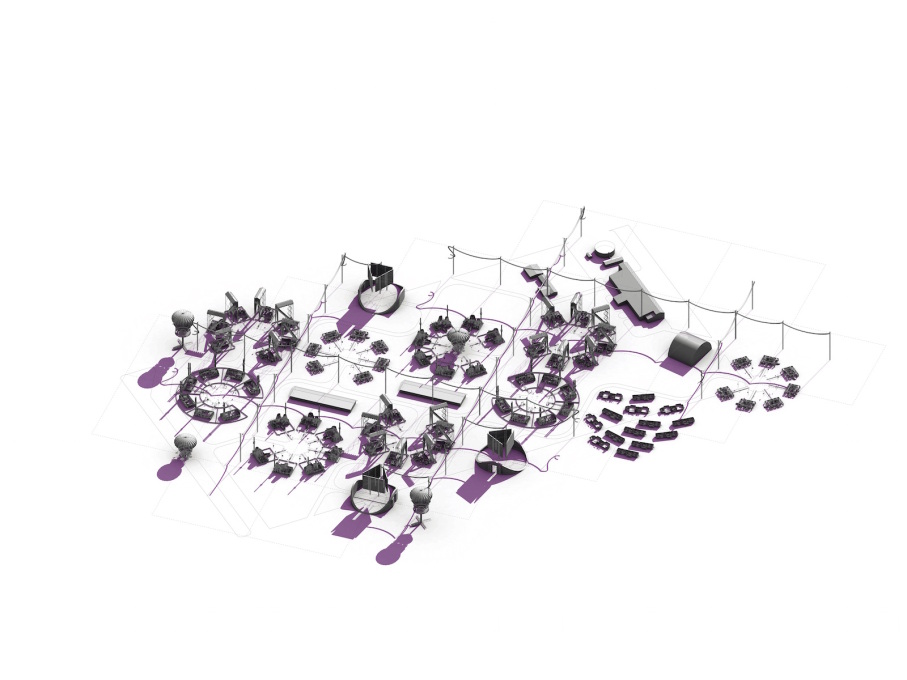

The DeathLAB at Columbia’s GSAPP, for example, presents a number of projects which use the latent energy stored in a body after life has expired to create public installations and spaces for memorial. “Constellation Park” imagines a new civic space in New York City, underneath the Manhattan Bridge, lit with thousands of cells powered by the transient, fading energy of human biomass. The result would be intended to provide an enduring “constellation” of remembrance – but one composed of a mix of newly lit, flickering and fading elements, in all reflecting the ephemerality of individual memories – and in contrast to “static stones asserting a false permanence”.

For Karla Maria Rothstein, director of the DeathLAB, projects such as this can encourage both existential and ecological reflection for the living: “We believe that these connections with mortality encourage valuable perspectives related to the finitude of our individual lives and our collective responsibility for our interdependent existence.”

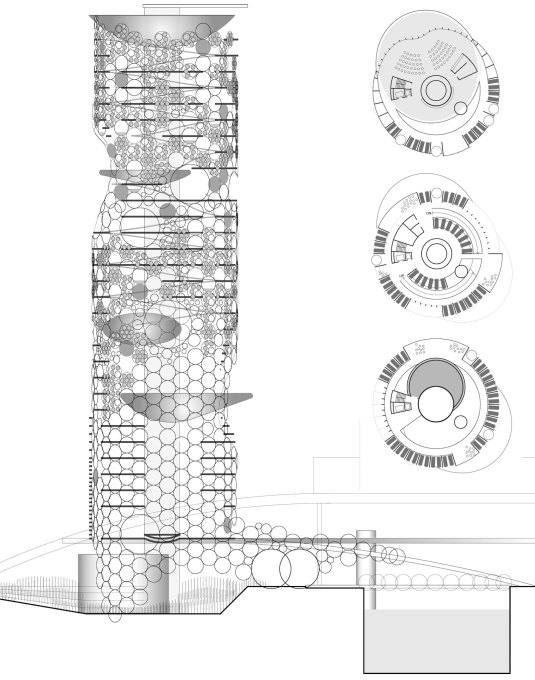

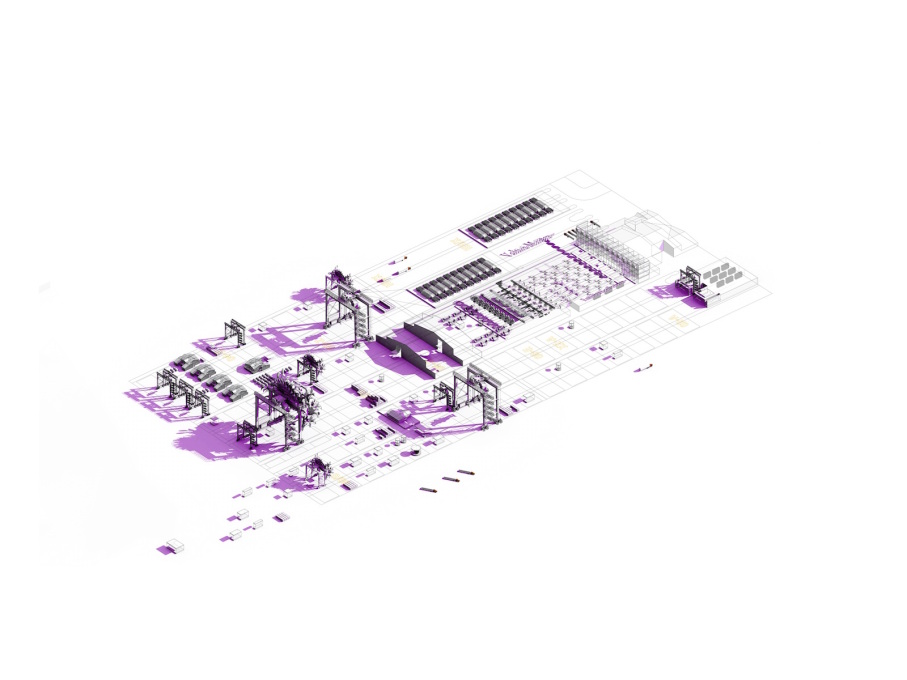

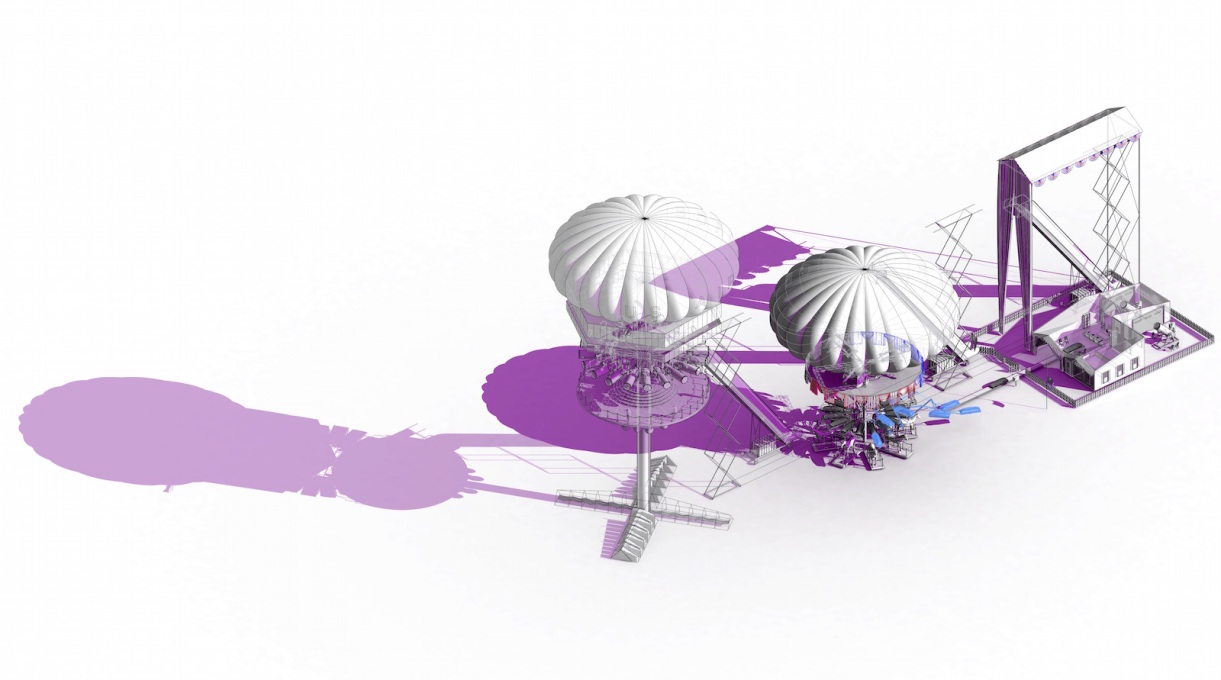

Igor Bragado and Miles Gertler from Princeton School of Architecture approach their research on death infrastructures from a similar angle, recognising the limitations of current attitudes and logistics around death and proposing a reintegration of death for positive social outcomes. Their “Transurban State of Death” project envisions the Dover Air Force Base in Delaware as a locus of interconnected facilities that process the bodies of the deceased for heat and energy, but also for virtual value, through the “Internet Legion Veterans’ Club”: a physical and digital space where family members might visit “server gravestones” which store the digital material (ie information from Facebook, Twitter etc. profiles) of the deceased.

As callous as “virtual value” may sound, Gertler and Bragado here acknowledge the digital nature of death in response to the tendency for large chunks of our lives to be lived out online. Social media have already been used as spaces for formal and informal memorialisation for years (Facebook has been operating “memorialised accounts” for its deceased users since 2009) and through this Veterans’ Club, Gertler and Bragado conceive of a location that is an intersection between the virtual and real worlds, forming new interactions between the living and the dead.

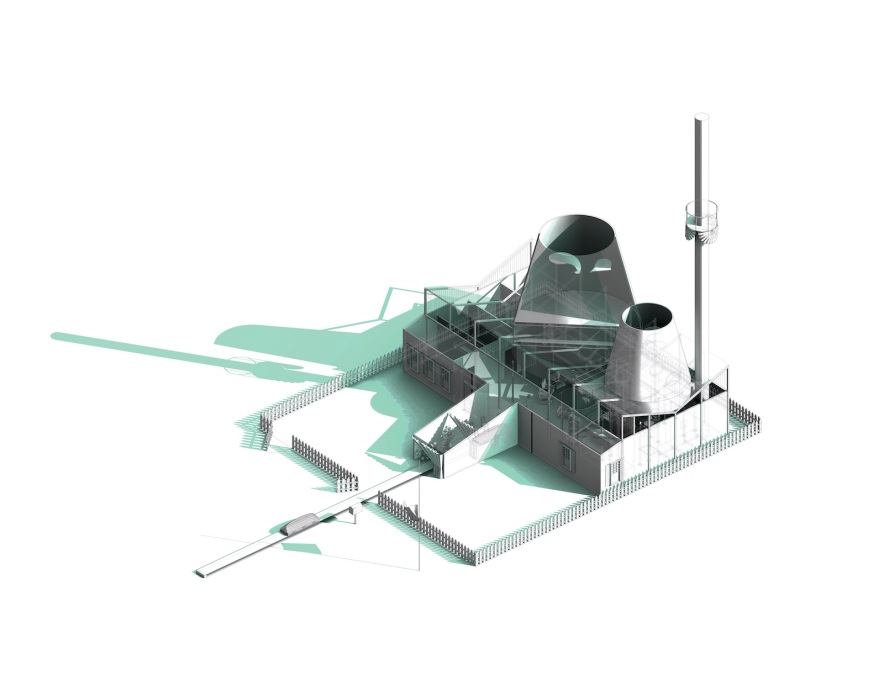

Before you dismiss these ideas as pie-in-the-sky academic speculation, think again. The DeathLAB have recently received funding to solidify the science and detail up a prototype of an anaerobic bioconversion vessel – the unit that will facilitate the conversion of latent human energy into the light pods of “Constellation Park”. In fact the use of dead bodies as an energy resource is already happening in the town of Redditch, Worcestershire in the UK, where since 2013 waste heat has been diverted from the municipal crematorium to heat a local swimming pool.

As expected, this proposal attracted controversy upon its announcement, but the local council was soon celebrated for its ecological innovation. New infrastructures and architectures for death will inevitably face public outcry when they arrive, but it is precisely this taboo attitude to death and the bodies of the deceased that the DeathLAB and Princeton researchers seek to challenge. As Rothstein explains, “Engaging the conversation on how we will address death in increasingly dense cities is an essential component of any serious investigation of urban evolution in the twenty-first century and beyond.”

The Princeton research has also found that public attitudes to rituals of death are not as rigid as we might assume. Gertler and Bragado found that in South Korea crematia has evolved from being a marginal and taboo practice to the preferred death ritual for ninety percent of the population within the last twenty years. This rapid change came as a result of the spatial limitations of an increasingly urban population, meaning traditional practices (domestic family-mourning ceremonies in a madang courtyard) were not feasible in apartment settings, illustrating how our attitudes to death evolve with social, technological and architectural changes.

What this research exposes is that to blindly persist with current orthodoxies in our infrastructures of mortality would be to the detriment of our urban environment and our relationship with death. The propositions put forward by the DeathLAB and Princeton researchers envisage a future where death technologies are “more socially productive, more desirable in urban terms, greener and more materially valuable” according to Bragado. Amidst these propositions and speculations, there is one certainty: death is coming. It’s up to us to decide how we deal with it.

– George Kafka

– Karla Rothstein is an architect and educator. Founder and Director of Columbia University’s trans-disciplinary DeathLAB, Rothstein is adjunct Associate Professor at Columbia GSAPP. deathlab.org

– Miles Gertler and Igor Bragado began their collaboration at Princeton University and founded their practice, Common Accounts, together in 2014. Their forthcoming book, The Architecture of Everyday Death, presents their research on the city and the business of death.

For more musings on architecture for the departed, visit uncube issue no.38: Death.