At the opening of the sixth Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism/Architecture in Shenzhen, uncube’s Rob Wilson found a confused curatorial structure and unclear theme – but also a timely reflection on the future of China’s Pearl River Delta region after years of breakneck development.

Arriving at the 2015 Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism/Architecture (UABB) direct by boat from an airport has familiar echoes of the Venice Biennale – except here it’s via the cavernous Shekou ferry from Hong Kong International rather than a packed vaporetto from Venice Marco Polo. And this feeling is reprised at the main exhibition venue housed in a complex of lofty dockside buildings – be it in Shenzhen’s case a recently disused twentieth century flour factory not the seventeenth century naval dockyard of its Italian counterpart.

This venue, the former Dacheng Flour Factory, defunct and superceded within a few decades of construction, perfectly fits the city-on-speed narrative that usually frames any discussion about Shenzhen. This is a city that famously grew from nothing to over ten million within 30 years, after being designated a liberalised “Special Economic Zone” in 1979 as well as sited in the Pearl River Delta, in close proximity to the Hong Hong trading hub, and the region that has driven the barnstorming rise of Chinese manufacturing over the past few decades.

The huge benefits this economic whirlwind has brought for so many in China has of course had many downsides too – witness the smog cloaking Beijing the same week the Biennale opened, for example. Indeed the macro-scale of the issues faced by Chinese cities explains why the UABB, since its founding in 2005, has specifically been focused on urbanism as well as architecture. It's a Biennale organised by the city of Shenzhen itself – physician heal thyself and all that – though interestingly its main sponsor is China Merchants, one of the major Chinese commercial distribution and logistics companies that supports the export-driven manufacturing boom – as well as being an arm of the Chinese Government. The big question now facing China as Doreen Heng Liu, one of the four main curators of the Biennale (together with Hubert Klumpner and Alfredo Brillembourg of Urban–Think Tank and Aaron Betsky) put it is: “Yes, we are prospering, but are we living well? The juxtaposition of the robust economic growth and deteriorated social and ecological environment… is not a happy one.”

And this year’s edition of UABB does feel something like a point of reflection after all this breakneck development. The Biennale’s title: Re-living the City, introduced by Gideon Fink Shapiro in the official catalogue, is all about re-use and recycling of the city fabric, as well as “the return of memory”: looking back to origins, drawing on existing and past conditions before looking to the future. Betsky framed this more polemically: “We have enough cities and built up areas. We do not need to make or build any more. [This Biennale] is about taking what exists and using it better. It’s not about building, but about unbuilding. Not about making boxes but unboxes.”

The thoughtful repurposing and reworking of the flour factory as the main exhibition venue seems a perfect illustration of this theme. The renovation of the main warehouse No. 8, designed and realised by Doreen Heng Liu – impressively in parallel to her curatorial duties – has made it fit for purpose as an exhibition venue. There are brand new stairs and access points, a new auditorium, outdoor performance space, classrooms, workshops, a café and bookstore. Liu has also brought a more speculative, imaginative side to the project with a new route slicing through the voids of the old grain silos, Gordan Matta-Clark style – creating a dramatic spatial journey, both soaring and claustrophic, that adds a touch of poetics to the pragmatics of reuse.

This real sense of recycling-the-city in action was somewhat undermined however by the admission that the majority of the site, despite the extensive conversion work, might yet still be demolished after the Biennale to make way for new mixed-use development, construction of which was already hemming it in on three sides. But in any case the theme of “Re-living the City” remains curiously out of focus and unexplored in the actual exhibits and projects selected by the four curators. Indeed the fact that there are four curators is perhaps the issue – each has their own exhibition section and distinct themes which only glancingly connect to each other and the main thread. So while Betsky’s Collage City 3D revisits the work of Colin Rowe and the idea of urban accretion rather than the totalising vision of modernism, Liu’s PRD (standing for Pearl River Delta) 2.0 looks at ways to reestablish the balance of environmental and social issues during the next phase of economic development. Meanwhile Alfredo Brillembourg and Hubert Klumpner’s Radical Urbanism connects to their own research into bottom-up, so called “tactical”, urbanism seen in informal settlements, and the lessons, practical, political and social, that architects and urbanists can learn from this.

It’s as though there had been an inability to choose between three curatorial proposals during the selection process, so all three have been run in parallel instead – explaining perhaps the very loose fit of the “Re-living the City” theme, one that only had coherence through the vivid orange and blue graphic identity designed by Thonik, who branded everything from catalogue, to guides, to leaflets, to posters.

A further layer to the opaque curatorial structure was added by the existence of a so-called sub-venue at Longgang curated by artist Yang Yong around the theme of “Sharing House”. This was listed on all the copious accompanying Biennale print material, but Aaron Betsky at the official opening press conference in Shenzhen City Hall, announced categorically: “We urge you not to go to Longgang. It is not part of the Biennale”, whilst later referring darkly to a second catalogue doing the rounds and two parallel education programmes.

Whilst at times this lent a slight touch of farce to the opening days, suggesting some doppelgänger biennial shadowing the real one, the open airing of unresolved curatorial and organisational tensions, ultimately ended up compounding the lack of a single driving vision behind the whole thing.

Nevertheless, this Biennale does provide a very rich platform for an astonishing array of projects and proposals, connected not so much by the theme of re-use per se, as that of looking at and learning from hands-on, research-based, bottom-up practice for lessons as to how to shape the city of the future.

So while in the Collage City 3-D section, Betsky revisits Rowe’s ideas of urban layering, he also explicitly references ideas of collage coming from art practice, of appropriation, reuse and critique of found objects by recontextualisation – and uses them here to reimagine and repurpose the city and its structures. For this he has invited a range of architects and artists he describes as “making structures and cities out of existing forms and materials” to create propositional installations drawing on the local conditions in Shenzhen to explore the “viability of architecture that is a gathering and a revealing rather than an invention.” While some of these installations seem to suffer from lack of time or budget, there are some vivid commentaries and cuts through the city, from the installation by Superuse Studios, developing a “harvest map” of Shenzhen, identifying sources of recycled building material such as including car industry waste and offcuts from tea ceremony tables, to TROPOTEC 1’s wall of tiny locally-manufactured mechanical music boxes, each identical except for the tunes they play, which arranged by composer Rebecca Saunders, create the “cacophony collage” of the piece’s title. Meanwhile Jimenez Lai’s installation is a lightbox of brightly coloured plastic goods re-imported from the States but each originally manufactured in the Pearl River Delta. These, interspersed with tiny plastic figures, are presented like buildings, arranged in a bright cityscape of colour. Interestingly Betsky’s section, by taking the idea of collage as the theme, feels more like an interesting contribution to the reassessment of post-modernist ideas currently underway, than any commentary on re-use or appropriation.

Less ad hoc visually, but focused squarely on a literal ad hoc urbanism, is Brillembourg and Klumpner’s Radical Cities section, with their own celebrated research into informal communities – such as the one vertically occupying the Torre David in Caracas – here reprised in a presentation of research work from around the world into other informal settlements and the issues that shape them. These range from the fascinating aerial surveys presented by Manuel Herz Architects of the refugee camps of the displaced Sarawi communities in the Western Sahara to the new urban forms developing in the informal settlements of Cairo, coming out of research by MAS-ETH Zurich.

Whilst this is unarguably fascinating and important research, giving visibility to those living in areas of conflict and the contested space of marginalised communities, it is not always clear what immediate practical lessons, if any, for wider application to urban development, especially in cities like Shenzhen, can actually be drawn from these examples. One exception perhaps being the work of Anna Heringer, Martin Rauch and Mu Jun, who’s project shows how self-built earthen construction might be reproduced at scale in an urban setting.

The Pearl River Delta 2.0 section, filtered through Liu’s reading of Henri Lefebvre’s The Production of Space, also focuses on “space making”. But here it is of what she calls the “in-between” variety, balancing bottom-up initiative and top-down planning. The projects shown here feel more cogent to action through being focused on specific local conditions, setting field research against provocative visions for possible futures. Juan Du’s work, for example, on tracing the origins of the urban villages embedded in Shenzhen, tells the lie to it being an “instant” city – there were over 200 traditional villages in the area before the 1980s with a combined population of 300,000. And WISE Architecture shows a provocative scheme for preservation of one of these urban villages threatened by demolition: reestablishing it vertically on the floors of the Dacheng Flour factory building itself. Meanwhile Christ & Gantenbein show off their research into the urban typologies of Hong Kong, with rows of frankly beautiful white models, providing a refreshing moment of serried calm, cutting through the fragmentary visual chaos of so many of the other exhibits. And MAD display a vision of a projected future where the whole mainland foreshore of the Pearl River Delta is populated with towers like Hong Kong’s, and propose to develop an island as a forested park at the centre of this new vast conurbation, like a floating version of New York’s Central Park.

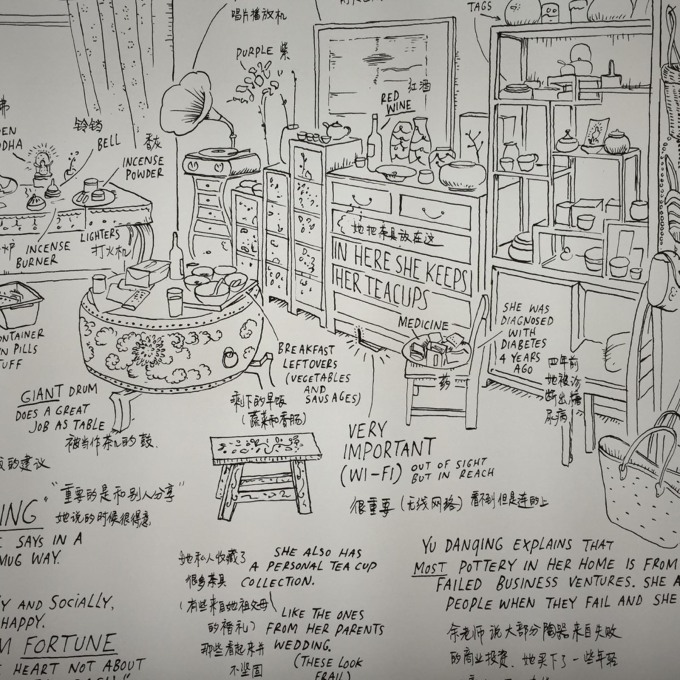

In the main exhibition venue are also a number of national and institutional “pavilions” with highlights including the Victoria and Albert Museum’s display Unidentified Acts of Design looking at morphing of notions of design in the Pearl River Delta outside the formal design studio; while the Irish Pavilion fascinatingly traces the story of Ireland’s Shannon airport, the world’s first tax free zone – visited by a Chinese delegation including Jiang Zemin in 1980s – and its influence as an economic model in the development of Shenzhen.

Other smaller sections including Social City – looking at social media as a tool of citizen-based participation, and Maker Maker – showing how digital and handcraft technologies are melding more and more together, feel more like they touch upon whole other Biennale-sized thematic icebergs that there is not the space to explore – their inclusion more about ticking the box of what’s fashionable at the moment – and not taking the debate further. This might be rectified however through the planned series of 180 events that will flesh out the ideas and issues raised in the exhibitions, with one major curatorial strand in this being the Aformal Academy, a series of sessions organised by Jason Hilgefort and Merve Bedir (uncube contributors both!), which promises to be a platform for debate and idea exchange for exhibitors, educators, foreign and local students, but also locals – from craftsmen to the public at large.

Indeed over 200,000 visitors are expected to come the Biennale. But even with these numbers, what is going on at the Biennale can feel more like dancing on the head of a pin against the huge scale of the surrounding city, a thought brought into sharp relief, when during a debate in the auditorium on the future of the Pearl River Delta, there was a comic reality check moment, when the chair asked if someone could get the person outside to stop hammering for a while – a hopeless request as it turned out that the noise came from a huge jackhammer far out in the construction site enveloping that of the Biennale.

en.szhkbiennale.org

Until February 28, 2016