The idea of deliberately flooding land as a defensive measure was developed in Holland from the sixteenth century onwards, later saving the country from French invasion in 1672, and reaching its most sophisticated form in the New Dutch Waterline built between 1815 and 1870. This astounding piece of engineering is an 85 kilometre long defensive line of military forts and fortifications, surrounded by land capable of being flooded through a complex system of locks and sluices, cutting Holland off like a virtual island. To commemorate this long redundant system, a new museum has opened underneath one of its largest remaining forts. Anneke Bokern visited for uncube, getting down-to-earth in a Dutch ditch or two.

Anne Holtrop is an outsider in the pragmatic world of Dutch architecture. While most Dutch architects succumb to the economics of the construction business and start their projects by fitting the required spatial programme to the available budget, trying to maximise what’s possible within the given restrictions, Holtrop turns this process upside down. His designs start with meandering shapes and spaces, to which any programme has to adjust. It's no wonder that so far, most of his buildings have been temporary pavilions, hovering on the border between installation art and architecture. But with the recently opened Waterline Museum near Utrecht he's proved that his philosophy can also be applied to permanent structures – even in the down-to-earth Netherlands.

The New Dutch Waterline is an 85 kilometre long military defence line, reaching from Amsterdam to the Rhine estuary. It was built between 1815 and 1870 and consists of 46 forts and five fortified towns as well as hundreds of locks and sluices. In the event of an invasion, a broad strip of land in front of the line could be flooded hip-deep, making it impossible for soldiers and horses to cross. The Waterline concept was invented in 1589 by Prince Maurits of Orange and put to use several times over the centuries, until airplane warfare made it redundant during the Second World War.

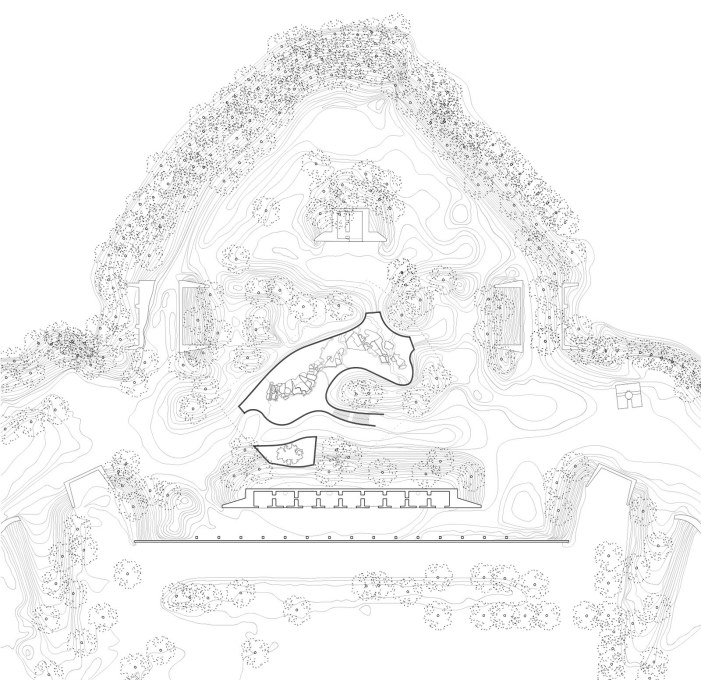

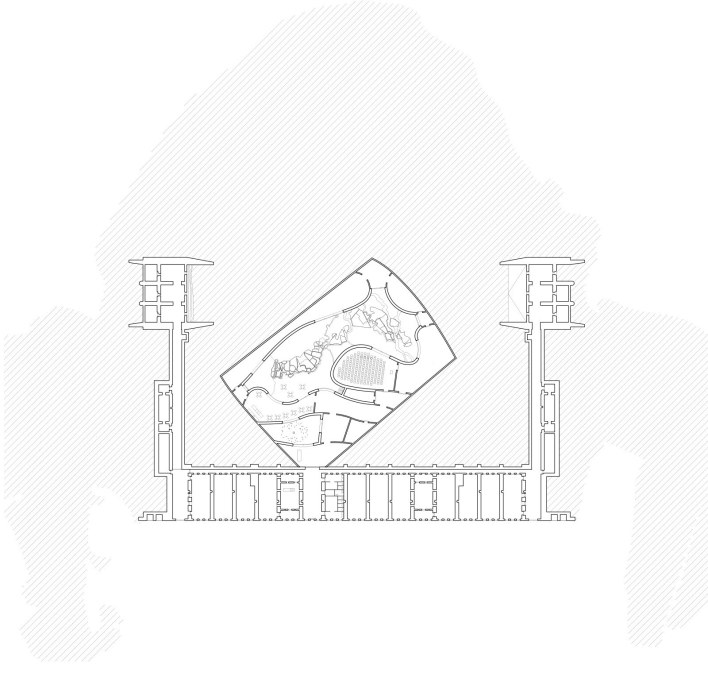

Fort Vechten is one of the largest and best preserved forts of the New Dutch Waterline. Which is why it was chosen as the location for a museum about this defence system, the remains of which still lie in the Dutch polder landscape like a giant piece of land art. Holtrop's approach to developing the museum design also seems to have been derived from land art. He traced the topographic lines of the core of the fort’s hilly site and then drew a rectangle around this shape. Between this rectangle and the topographic lines lie the museum rooms.

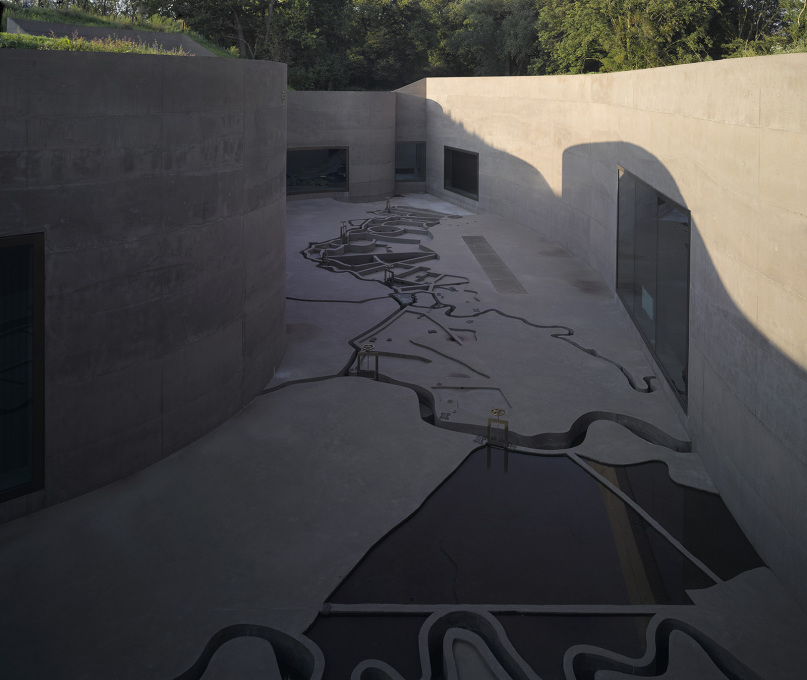

“For me, architecture is not an answer to a question”, Holtrop says. Instead, designing for him is a process of exploration, producing an interesting element of uncertainty in his buildings. Approaching the Waterline Museum from the entrance of Fort Vechten, it's completely invisible, being buried in the hill with no exterior façades. Access to it is hidden in the back wall of an old barracks building. A dark, humid corridor leads into the first room, which opens towards a small patio planted with ferns and a large patio with eight metre high curved concrete walls. In line with the sombre, ascetic atmosphere of the military fort, the concrete is purposely rough, with visible seams, and has an indistinct, brownish colour. The museum rooms, housing an interactive exhibition about the history of the Waterline, are arranged as a continuous sequence around the patio, ending with the café and then leading back to the entrance and shop. Three metre high curved windows with brass frames provide a constant visual connection to the large patio. On the ground of the patio there is a 50 metre long concrete model of the Waterline, that you can walk on, with all the forts and fortified towns made from brass. Visitors can inundate the model by turning water wheels to open or close miniature locks.

There's an interesting tension between the interior shape of the building, with its fluid, poetic curves, and use of materials, reduced to just concrete and brass. Holtrop doesn't like to speak of minimalism, but rather of reduction in his designs: they're about removing the unnecessary until you're left with only the essentials. A few years ago he visited the ancient town of Petra and was intrigued by the fact that the desert tombs, cut out of the landscape, are a result of a process of reduction. This seems to have served as an inspiration for the Waterline museum, which, conceptually speaking, is also excavated from the (artificial) landscape. In order to fully understand its layout, one needs to climb onto the grassy landscape of the roof and view it from above. Then it becomes obvious that this is camouflage architecture with sandbags of character.

– Text by uncube correspondent Anneke Bokern