In 1999, the American architect John Hejduk (1929-2000) visited the Heinz Galinski Jewish School in Berlin, designed by Zvi Hecker. Hejduk dedicated a rather dark and arrestingly poetic text to the building, a shortened version of which uncube presents here as a viewpoint to add to our kaleidoscope of all things Zvi around our issue no. 41: Zvi Hecker.

I.

Zvi Hecker's recently completed Jewish Community school in Berlin must be considered one of the major works in our time for its thought-provoking energy that makes us think deep about many things related to life and architecture, not least about the meaning of knowledge, expulsion, place and death.

Zvi Hecker’s architectural plan of the Jewish School is unique in our time, it cuts into the heart of what matters. Surely it is about the renewal of hope, as it is surely about the inner anguish that brings us face to face with the past and the impact of the enormity of the loss. It has the joy of innocence, at first, yet it is shedding architecture. It sheds its first skin, or is in the process of doing so, in Berlin.

II.

The first time my wife and I crossed the Berlin Wall into the then East Germany it was with a fair amount of trepidation. We were certainly disturbed and uneasy as we passed by a prison where prisoners were shouting at the passers-by. It was grey. The buildings, the sky, the people, grey.

When we entered the museum there and were confronted with the Paragon Hellenistic marble friezes, I was stunned. There were many snakes within the work. Man and snake. Those images have never left me. The writhing of the snakes and the men.

We then proceeded to the room where Persephone was. To see her, impregnated our souls. The light in the room had a grey mist. You could see the particles of air at times giving off an opaque crystal light. Persephone was in a contained room in Berlin. A year or two later we returned to gaze at her again, but she was no longer in that room, it was empty ... had she returned from the Underworld to her beloved homeland, far to the Southeast? Her departure left us with a feeling of foreboding.

In the same year we were able to visit the Archaeological Museum in Athens. We arrived almost at closing time and few people were left in that haunting place. We looked at the sarcophagi surrounded by sculptures of the dead mother, father, and child, domestic animals and strange winged creatures – man and beast. The conclusion I came to was that these creatures were simply unimaginable. They, too, as the mother, father, child ... were.

In Solopaca, Italy, in 1953, I walked up a hill covered in olive trees with my wife's eighty-year-old uncle; we started down the hill on stone stairs. On one side was a high wall of stones, on the other side the olive trees. Suddenly in front of our path a large black snake slithered in front of our feet. I was taken aback. I said to Uncle America: “Did you see that snake?” He replied: “What snake?” – “The one that just crossed our path.” – “No, I did not.” In amazement I said: “How could you possibly not have seen such a large snake?” He calmly replied: “I do not believe in snakes.”

A friend of mine, an anthropologist, related an ancient story where one of the gods becomes an immense snake that eventually swallows up everything in the world, even the air. I thought to myself that that god snake had swallowed up everything outside in ... nothing left ... nothing to fear. The exact opposite of living life, and of understanding its sacredness.

III.

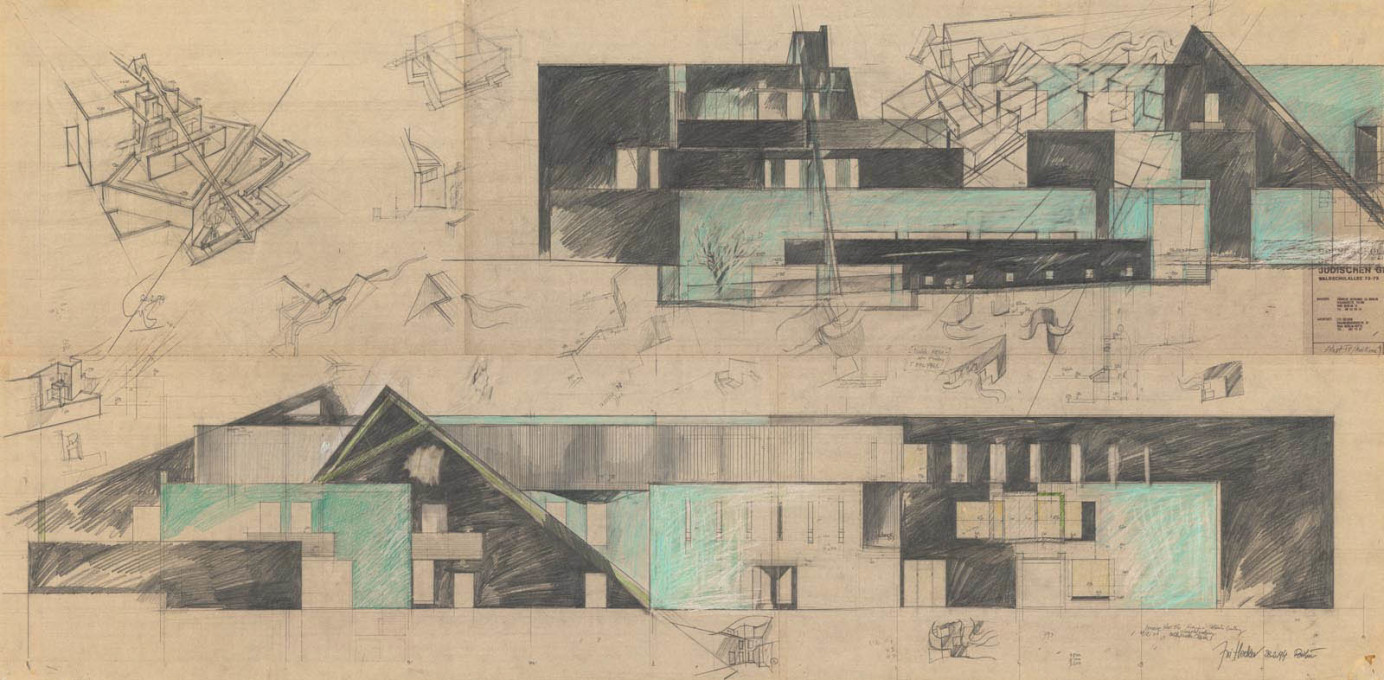

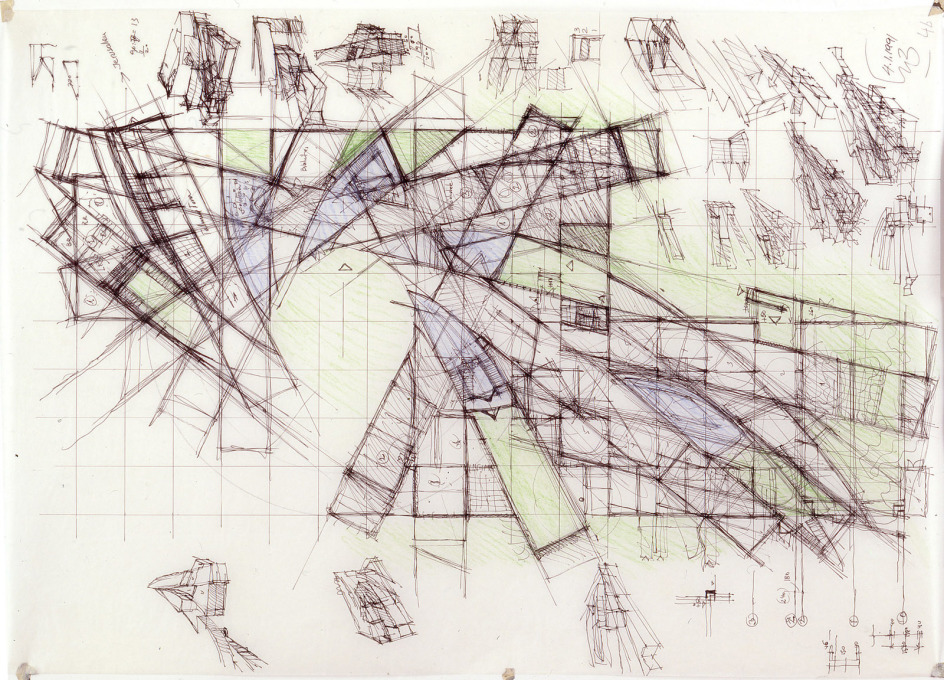

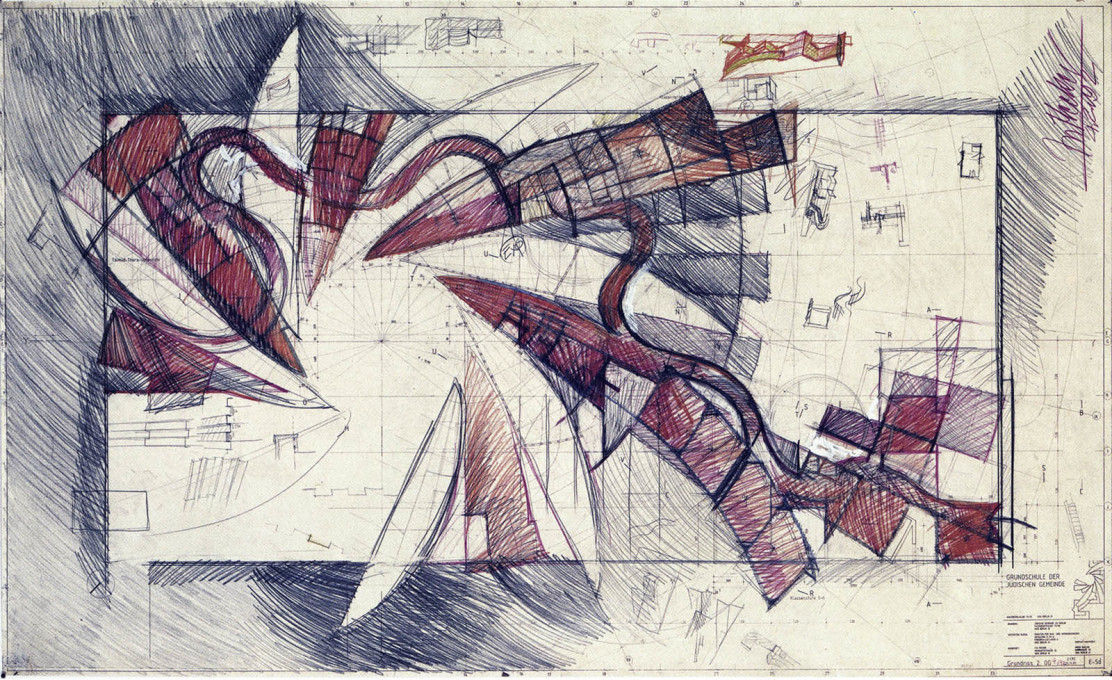

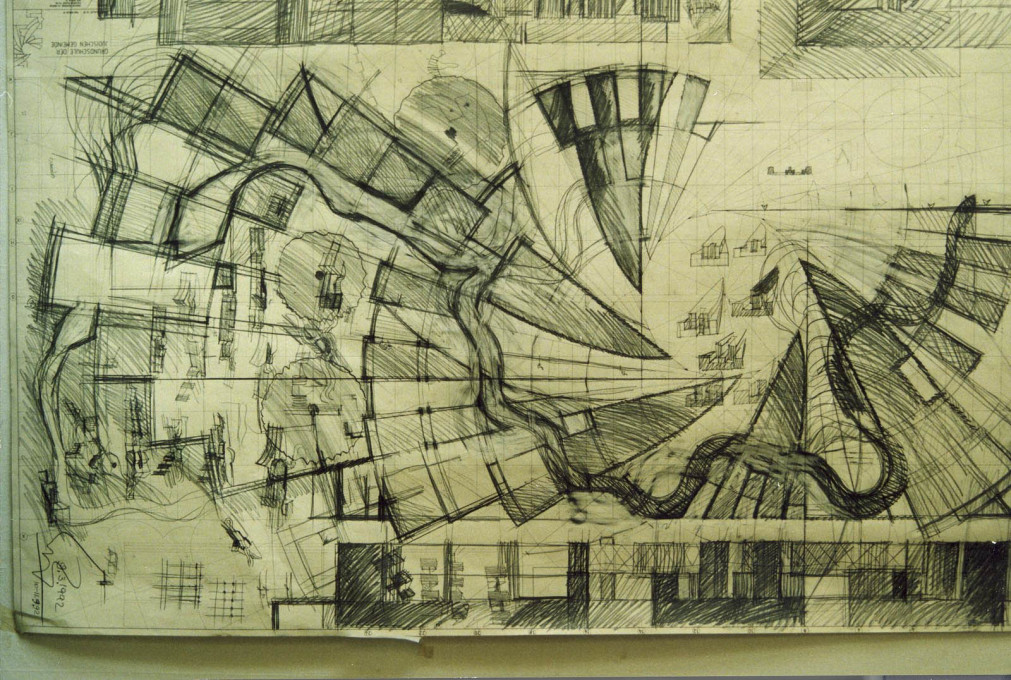

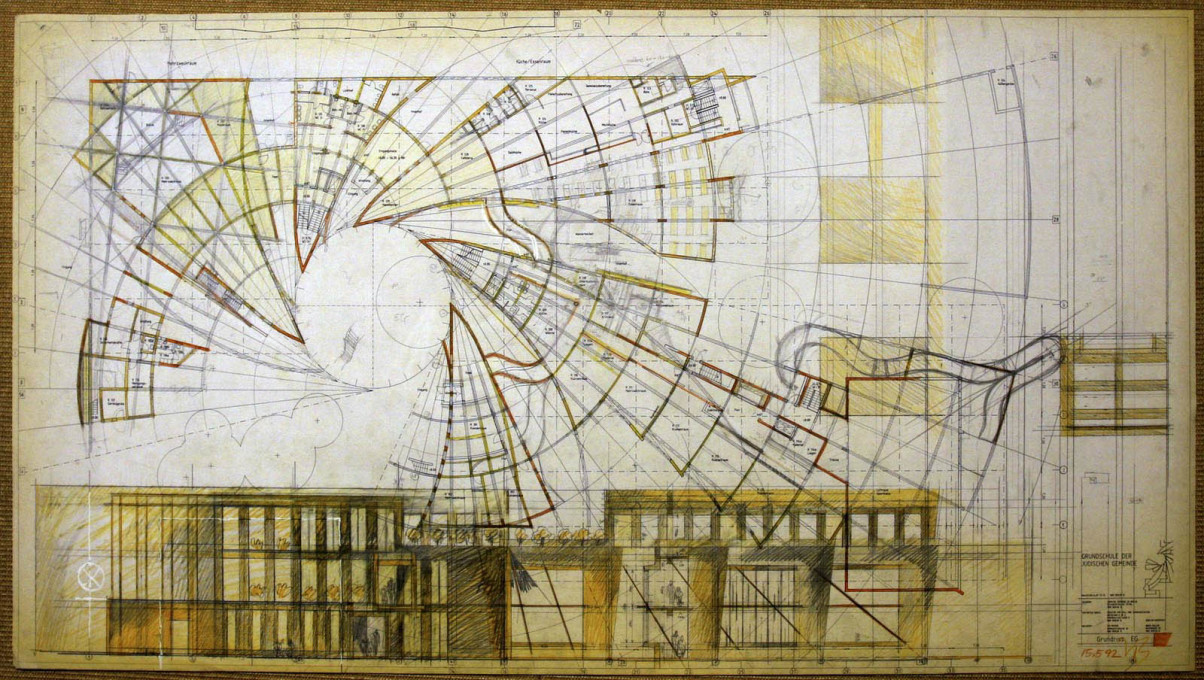

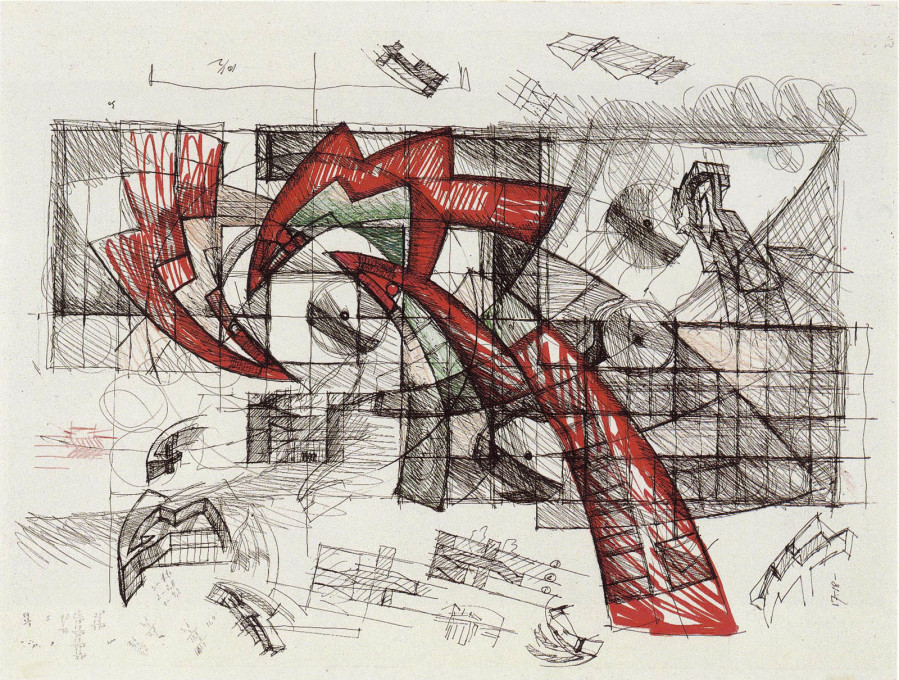

Some aspects of Zvi Hecker's Jewish School that I wish to touch upon are his initial sketches, black and white and coloured, his technical black and white plans and the axonometric, the built building as well as the programme and some thoughts on its possible underlying meaning.

But before I go into the above thoughts, let me make a brief observation about Zvi Hecker's spiral apartment building in Ramat Gan, Israel, as it is a sister of the Jewish School in Berlin. In Israel, the process is one of peeling, too. The Spiral Apartment House is one of the few Cubist buildings that were ever built. And it is from the Garden of Eden. When asked about its meaning, Zvi alludes that it perhaps has something to do with Paradise. I think it has to do with the concept of peeling. It is like taking an apple and in one continuous knife-cut peeling the skin off – for a split second the apple appears white, then quickly begins to fade to another, darker colour. The inner core of the apartment building is like the apple: a hard core of rough stone and inner planar fin-like flying structures with amazing reflective mirror panels (the reflective seeds). The outside wall of the curving spiral is smooth stuccoed, revealing exposed stone frame openings, and stone wall ledges. Yet once the apple is bitten some agony is to be expected, for the building is literally punctured with planes of metal shafts partially serving as external balconies (heads of piercing arrows). The building remains as stoic as paintings of a martyred saint's body filled with arrows. On one of the building's ledges (of rough stone) there appear to be petrified stone snakes taking in the sun. Antoni Gaudí was equally interested in snakes within architecture. While visiting Paestum in 1953 late one afternoon I saw a snake resting on the top of one of the temple's capitals. After all these years it never occurred to me until now how it got there.

IV.

Zvi Hecker's arrival in Berlin to construct the Jewish School was a lifetime's journey from Poland to Samarkand, to Kracow, to Israel and then to Germany. Another journey from Poland to Israel, then to America, then back to Europe, and on to Berlin was taken by Daniel Libeskind who is presently constructing the Jewish Museum in Berlin. The Jewish Museum and the Jewish School are the most significant and creative works built in Berlin in recent times. They bear witness to the indomitable spirit of a people. Libeskind's museum is a lightning bolt signalling within its architecture the sacredness of life – and its mystery. At another end of the city, Hecker's school is the celebration of learning, education and hopeful hearts. That these two men came to be in this place at the same moment is cause for serious thought about predestination.

V.

The Jewish School is an architecture of shedding. Zvi insists on the word precision regarding the building. And precise it is. Also it has clarity, sharpness along with perfection in detail. The program is impeccable. These equalities are to be expected from an artist such as Zvi. I appreciate these qualities, but there is more, the hidden. For the hidden we must go to the sketches and the extraordinary coloured/pencil drawings. It is in their depth of evolving thought that lies, I think, the deepest of soul-meaning. These drawings present us with the workings of a mind as it creates. They reveal the psyche and the revelations within its struggle to unearth, to search, and to discover. Zvi refers to the plan as a sunflower. It can be that, but in Berlin it is more and possibly otherwise. There is a snake curling through the sunflower petals. There, too, is a snake in the garden: The explosive sketches, the line drawings of the overwhelming movement of the snake as it startles. Zvi draws and renders the petals and snake over and over again. He is obsessive and appears to be exorcising something throughout and out of his drawings. He begins to erase parts of the connecting snake with the educational volume. His coloured drawings are filled with fire, blood and darkness. It is his struggle to cleanse.

Originally there was no snake in the plans, then it appears and moves through the plans and drawings, through the pages of the house of the book. The sunflower petals become knife blades, the curved triangles become places of learning, they cut and segment the snake out of the spaces for learning. Architecture and knowledge kill the snake. Its outside remains as a memory of past evil-doings but it remains. It must be remembered, not forgotten. The sun beats down on its metallic empty skin that remains. I have said this building is about shedding, but it is also about solidly fixing memory. The expulsion and killing of a people can never be permitted or tolerated. Zvi’s anguished drawings serve as a warning, hidden at first in his internal/eternal book. The blades can metamorphose back into the sunflower petals as expressed in the built work in the enclosed garden in Berlin.

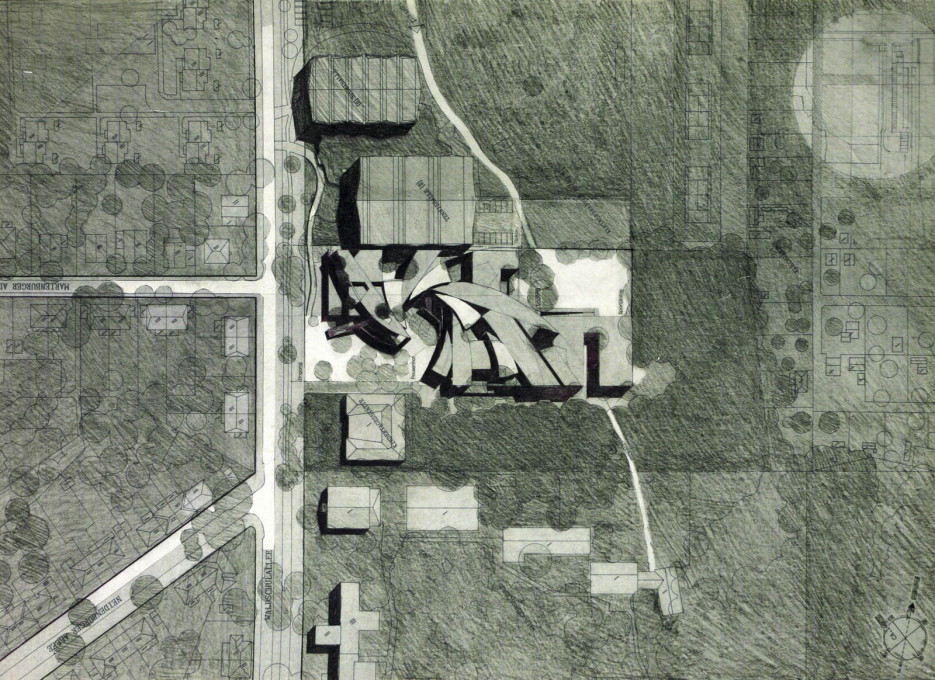

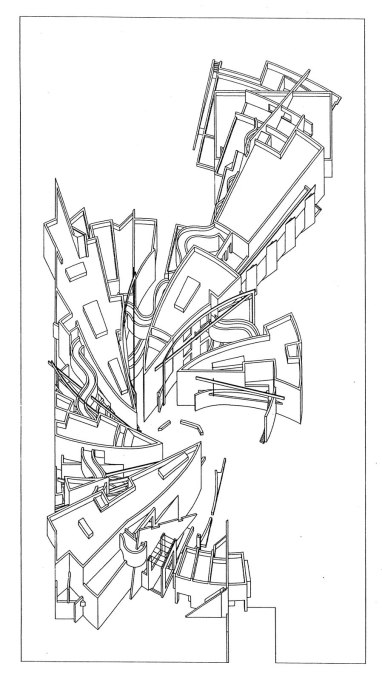

The subtlety of Zvi’s mind and the mastery on his discipline is first expressed in the black ink of his plans and the axonometric of the building. There is nothing like these plans. One of the most radical plans is presented as a gift to the public. It is one of the most dynamic, kinetic, riveting plans in the history of architecture. The organisation of the plan is brilliant, precise, and exhilarating. The precision, which Zvi speaks of, is in this plan. Every student of architecture should study these drawings and the coloured sketches. In the built work the five curved wedge volumes moving around a centre are like five land-ships ploughing through a sea of earth to their destination, a centre of learning. There should be a well in the central section of the site where the seeds of thought can be dropped into the water, mixing together for the birth of new thought.

The five curved wedges are themselves shedding. They attempt to shed their skin of the past. They leave shedded metal structures, and we can see the metal trusses shedding their encasements. The tall metal columns support the horizontal free buttresses exposed to wind, sun, rain, snow, night, day. These floating structures are the first shedding. The wedges close to the land-ships near the ground produce a second peeling, a second shedding takes place, making way for the birth of a pure white prow, for this whiteness is the innocence of children learning ... to be free.

Within the triangular volume, there is a classroom where the triangular wedge shape exaggerates the diminishing internal perspective and an inversion takes place. The last school desk in this room is placed in the apex of the triangle. As the triangle widens forward to the end of the triangle (where the teacher must be), the desks increase in number from the distant apex. The faces ... most students facing the teacher are in the front of the class … the teacher overlooks the sea of faces and sees in the distant apex a single child, the last one. Behind the child is the vanishing point.

Zvi has created a masterwork, a house of the book. Perhaps sometime in the future the present fence surrounding the school's site might metamorphose into a wall of books, two books thick; one side, the outside public space, for the outer reading; the other side, the inside exterior garden space of the school for inner reading. I have studied and read Zvi Hecker's book and I thank him for his gift to humanity and to the children most of all.

– John Quentin Hejduk (1929-2000) was an American architect of Czech origin, who studied at Cooper Union and Harvard GSD, from which he graduated in 1953. After working in several offices including that of I.M. Pei he established his own practice in New York City in 1965 and worked as architect, artist, writer and teacher until his death on July 3, 2000.

This text is a shortened version of the original text Sunflower: Snake: Persephone: Berlin as published in House of the Book, Black Dog Publishing Ltd., London, 1999; with texts by Peter Cook, John Hejduk and Zvi Hecker, reproduced with kind permission of the publishers.

Further reading: uncube No.41: Zvi Hecker, of course. See also our interview with Daniel Libeskind, from our Radically Modern series, about his experiences of building in Berlin.