Vaudeville and vodka marked the first 2016 debate organised by Turncoats in London featuring Charles Holland (ex FAT), Adam Nathaniel Furman (The Postmodern Society), Jane Hall (Assemble), Bertie Brandes (The Mushpit) and Rory Hyde (V&A Museum). But alongside the laughter there is refreshingly unfettered exchange. Ellie Duffy reports on the first Turncoats event of 2016‚ the hugely popular new format whose self-confessed mission is to shake up architectural debate until its teeth rattle.

How fitting that the first debate of the 2016 Turncoats series, with its proposition “Ornament is crime is crime”, took place in London’s Hoxton Hall, an East End music hall built in 1863 to provide entertainment for the working population but repurposed in 1879 by a temperance group to promote abstinence and restraint – presumably to much the same audience.

There is more than a hint of the vaudeville in the Turncoats format, which pits opposing teams of speakers against one another in traditional style but with the theatrical twist that you’re not quite sure who’s playing true to type and who devil’s advocate. Previous debates in the series have included Quit Architecture Now and Vanity Publishing: a distinct departure from the “lukewarm love-ins” that the organisers feel characterise far too much of architecture’s public discourse today. To prime the audience, Turncoats events kick off with a comedy warm-up act and the downing of freely available vodka shots is enthusiastically encouraged.

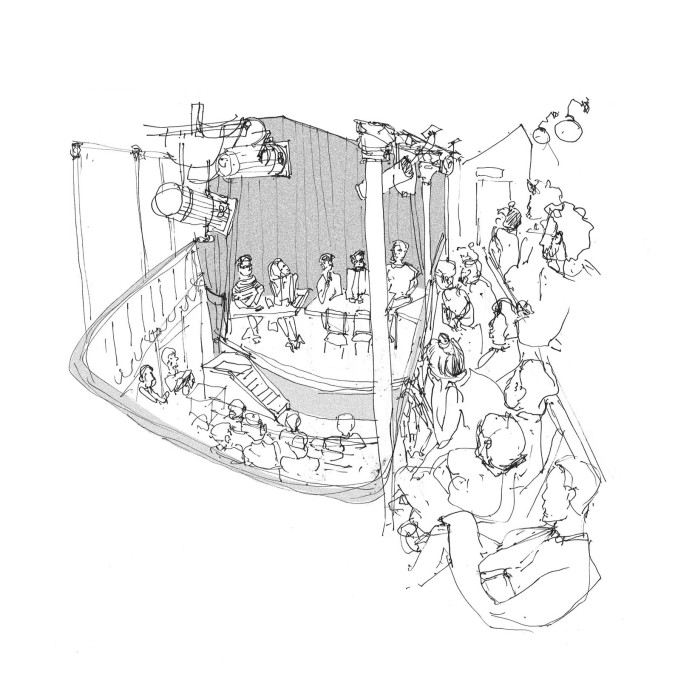

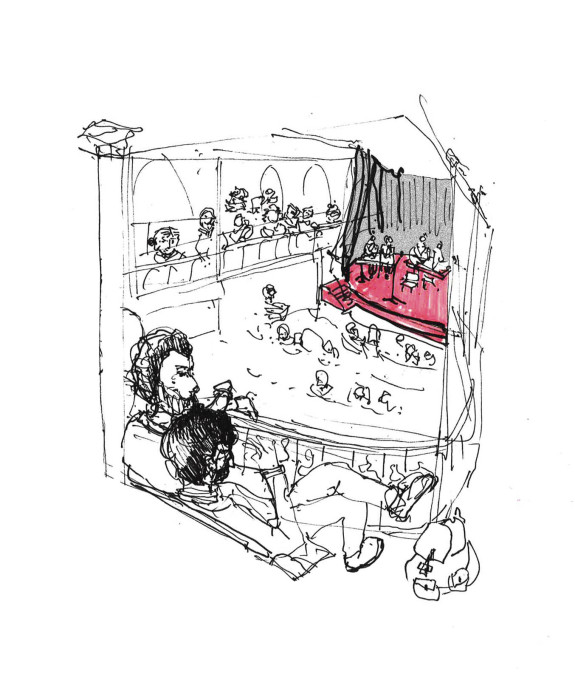

The debates have proved hugely popular and it was queuing and standing room only in the narrow theatre, with stalls and tiers of balconies above brim-full of a predominantly young architectural crowd, keen perhaps to be part of a revisionist take on the old modernist chestnut – originating from modern movement pioneer Adolf Loos – that ornament is crime. (In his essay of 1910, Ornament and Crime, Loos famously challenged the ideology behind the aesthetics of fin-de-siècle and Viennese secessionist architecture.)

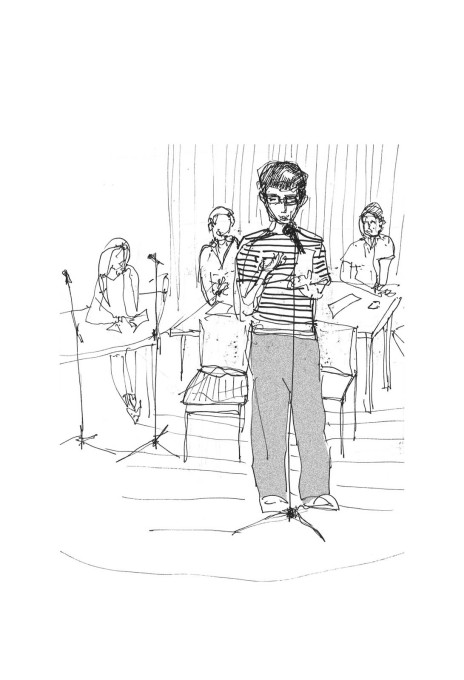

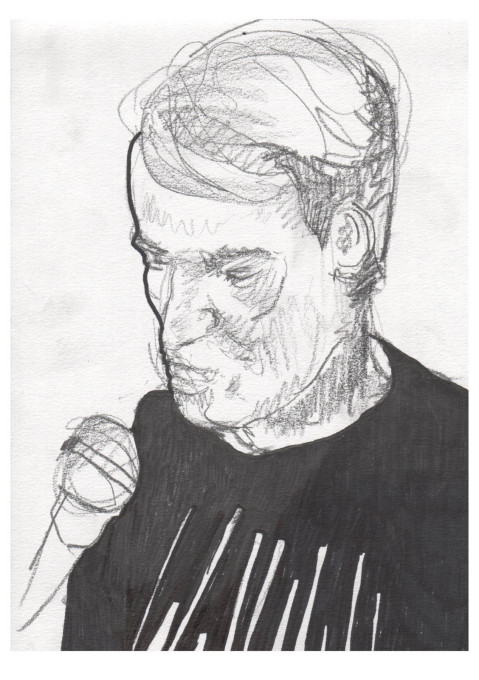

This debate was expertly chaired by the highly un-impartial Charles Holland of Ordinary Architecture, hitherto partner at FAT, the (now sadly defunct) practice fêted for its clever and witty undermining of the orthodoxies of modernism in projects such as A House for Essex with artist Grayson Perry. Holland immediately christened the anti-ornament team “the hair-shirted whisperers”.

Conversations veered energetically and erratically between the orthodox: “ornament is a weapon of obscurantism”; the tried and tested: “Mussolini was a minimalist”; and unexpected angles: “an aesthetic snobbery apparently based on restraint – just like David Cameron’s ‘Austerity Britain’”. Wit and parody were strongly evident; earnestness and seething passion in moderation.

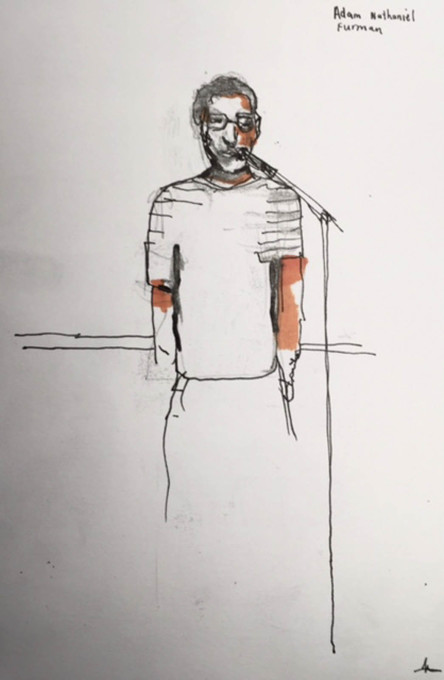

Opening the debate, architect-designer Adam Nathaniel Furman – a Rome Scholar and founder of Facebook group The Postmodern Society – began a spirited attack on modernism’s “fetishising of absence” in its boring obsession with shadow gaps and concrete finishes. (An absence, he claimed, not unrelated to overly complex spatial organisation in contemporary architecture – but I’m less sure about that). Decoration he declared is akin to an inalienable human right, arguing that it is human instinct to decorate both ourselves and the space around us: “You wouldn’t wear the same thing all the time…ornament is clothing for things, if you like”. “Saying ornament is crime” he concluded “is cruelty to humans and should itself be a crime”.

Jane Hall, a founder of Turner Prize-winning architecture collective Assemble, bravely defended modernism’s essential suspicion of ornament, defining it in specific relation to the built environment as superfluous decoration, probably expensive and quite possibly with the function of covering things up: “And will any architect admit to that?” she asked. She made a distinction between the separate roles of decoration in civic and private realms, asking – importantly – “Who’s doing the decoration?” and pointing out that historically ornament in architecture has often been a top-down imposition, “an intimidating layer of meaning dictated by someone else… [decoration] promotes the status of the individual client or architect and is therefore essentially against communality”. For allegories in ornament to work, she concluded, “we need to be co-producing our built environment – valuing our own individuality together”.

An outsider view from the world of fashion was provided by the next speaker, Bertie Brandes, a journalist, stylist and co-founder of satirical magazine The Mushpit. Her argument hinged on the premise that it’s impossible to separate this debate from politics – in particular the housing crisis in the UK, which has split the population into two distinct groups, homeowners and renters. If you’re one of the latter, she argued, landlords and short-term insecure tenancies will soon put paid to any aspirations to personalise your home.

Brandes also offered up a potential parallel between the ideologies of the architecture and fashion industries in the form of the story of normcore, the street trend picked up by the industry and then processed as the fashion joke of 2015. Instead of rejecting outright what are actually symbols of economic austerity, she argues, the fashion industry needed to “recontextualise” them through a lens of irony before essentially dismissing them. Are architects and “mind-numbing minimalists” perhaps guilty of this kind of substitution too?

The final panelist, Rory Hyde, curator of contemporary architecture and urbanism at the Victoria & Albert Museum, provided three “rock-solid examples of why people who like ornament are criminals and degenerates”. The first was Donald Trump: “What kind of abode does this guy retreat to after a hard day berating minorities?” Hyde asked, “Go on, Google his apartment – it’s a baroque bucket of bollocks”. The second was Hitler: “To let off a bit of steam Hitler liked to draw architecture. It was his pet project”. All the evidence shows that Hitler’s architecture was “ornamental, neo-classical, the full works – ringing vaults, statues…”

The crowning example from Hyde was the word of Pritzker Prize-winning “half-house” architect Alejandro Aravena, who he once hosted at a conference in Australia, along with Sam Jacob of FAT. Chatting to Aravena after the event Hyde asked if he could see any parallels between his own work and that of FAT, for instance their social housing at New Islington in Manchester? Aravena’s response was so emphatically “no”, Hyde claims (“They’re playing with the lives of people. This isn’t a game”), that “by that logic FAT should have been locked up. But here they are on stage!”

So all highly entertaining. Turncoats has achieved a great thing in re-packaging architectural discourse to engage audiences rather than merely participants. As a snapshot of the architectural profession, though, perhaps more telling was what remained unsaid at this event. While there were plenty of jokes about dictators and gold taps, nobody, it seemed, was quite prepared to stand up for architecture’s eroded role as an important contributor to society through the state. In the great top-down, bottom-up debate the truth is that generations’ worth of architectural expertise has very rapidly been marginalised by disinterested governments. Was I the only person, as the happy audience spilled out into the chilly winter’s night, to feel a little saddened to witness a brand new generation of UK architects seemingly so unconcerned at having been debarred from the engine rooms of the very programmes architects once helped to forge: the delivery of housing, schools, hospitals and public services, the design of the urban realm, the planning for the future. Or is that just fuddy-duddy modernist thinking?

– Ellie Duffy is a director of the graphic design agency Duffy, London. @duffydesign

Further reading: For more Turncoats tomfoolery, head over to Shumi Bose’s interview with organisers Maria Smith and Phineas Harper for uncube: Fights of the Round Table.