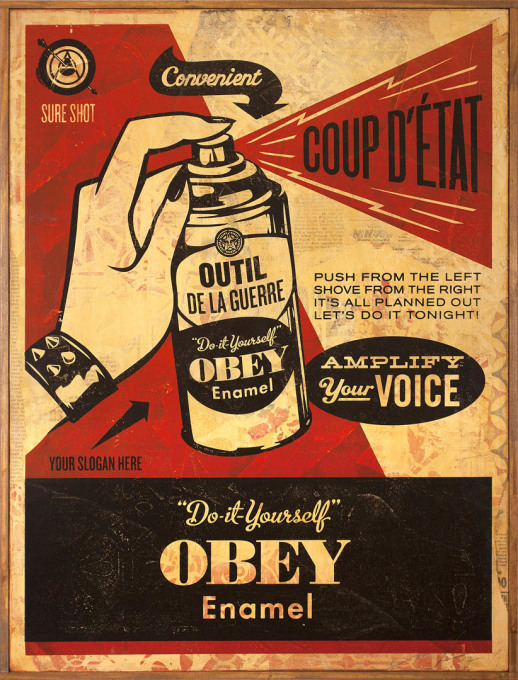

Vilified as a symptom of social breakdown on one hand, co-opted as a tool for gentrification and fashion marketing on the other, graffiti continue to exist on the fringes of social acceptance and legality – and can attract either high prices or high fines depending on which side of the fence you are sitting. Approved by Pablo (A(by)P) is a collaborative arts curation and production organisation whose latest exhibition, Venturing Beyond, seeks to challenge prevailing conceptions on the practice of graffiti and street art. uncube’s George Kafka spoke to curator and researcher Rafael Schacter following the opening of the show in London.

“Venturing Beyond” is a part of Somerset House’s “Utopia” season, but graffiti and utopia are not usually associated, how do you see these two fitting together?

The idea of graffiti as something utopian had always been present in the research that I’ve done, but it’s something totally opposite to how it is traditionally imagined. There is this prevailing idea of an artist alone in the night, hiding away. What is actually so present among those who practice graffiti is the strong community dynamic. This community also has a way of interacting with the city and space which is so utopian in its essence: so free and open and levelling and just really beautiful. So it was just about finding a way of expressing that which is so different to the traditional understanding of graffiti.

Do you mean its perception as vandalism/crime?

Yes and no. Graffiti is shorthand for dystopia in the media. Whenever you are talking about something socially negative you have to go somewhere with tags in the background, or on the other hand it’s shorthand for creativity, but in its worst dynamic: creativity as “innovative creative hubs” and regeneration, which is my dystopia.

So how does the idea of “venturing beyond” come into it?

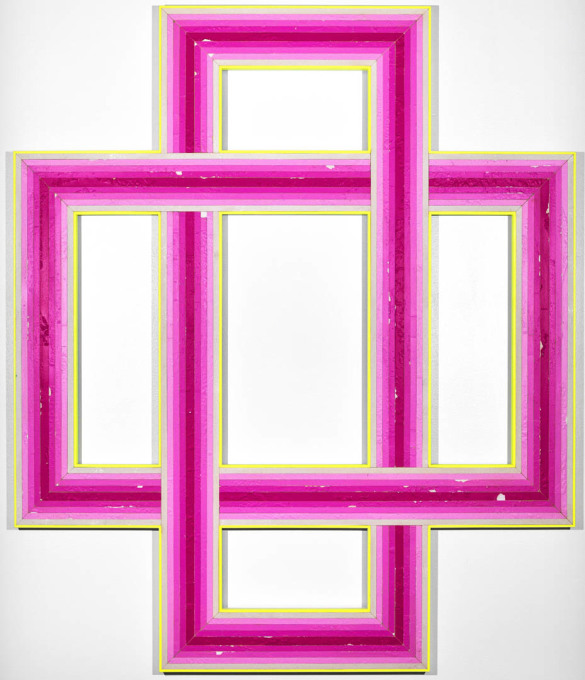

You can see the idea of venturing beyond in a number of ways: spatially you’re venturing beyond architectural restrictions in the city. Secondly, these artists venture beyond aesthetic restrictions, so you’re trying to go past boundaries aesthetically and also in terms of the idea of art. But there’s also an idea of going beyond social norms; you’re creating networks and communities outside of everyday normal practice. If you think back to the pre-internet days, graffiti artists were essentially penpals. The way people interact with each other, locally and internationally makes the community of practice that is formed and the bonds that are formed so strong.

You mention going beyond spatial boundaries, those boundaries are more sharply defined in our cities than ever, how do you see the practice of graffiti and public art responding to that?

The city is becoming more and more restrictive and places of play for artists are increasingly disappearing. I think Eltono’s work in this exhibition, which he did site-specifically at Somerset House, alludes to this. It’s not just about finding places outside of the everyday. It’s about using the places of the everyday in a different way. I think that’s what graffiti enables; a way of looking at things from a different perspective. So even if those places are disappearing that mind-set is now radically changed. I think those moments of crossing boundaries can still occur in spaces that we all encounter.

So it’s about playing within the restrictions that exist?

Yes, but it’s also going past those restrictions. Since the beginning of graffiti those spaces of play have been increasingly restricted, through technology, through the “war on graffiti”, and the more regenerated they become the less these kind of urban backwaters exist. Les Frères Ripoulain did a great piece in our last exhibition where they showed all the empty spaces in the city where they used to work and how those have all become refurbished. Of course those spaces becoming regenerated can be good for a lot of people depending on the situation, but these urban wastelands were play areas for some, even though they were dead areas for others. I think whilst those areas are becoming fewer, the way you relate to the city becomes totally reformed. That way of interacting can happen anywhere.

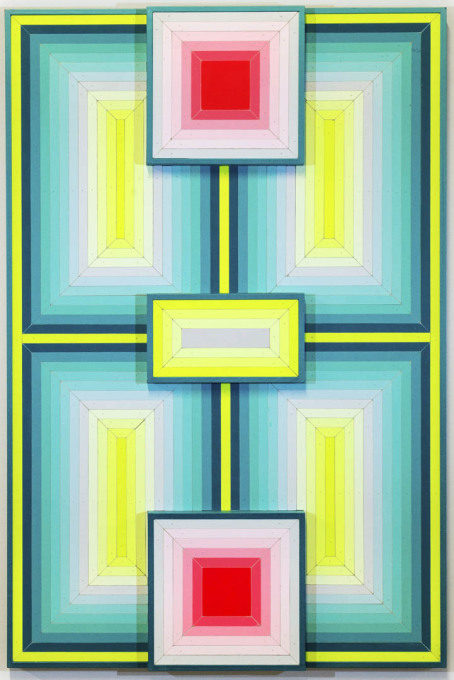

Eltono is a master of using the spaces of the everyday in his work, can you talk me through his piece for “Venturing Beyond”?

He was here for a week before the exhibition and he basically used the Somerset House courtyard to create a game. He delineated a certain area and he would walk clockwise round that area until someone crossed into the area and he would then have to reach their entry point. Then if someone else came into the boundary he would have to reach their entry point. And then once you reach that entry point you carry on circling. Then he created a drawing from that experience. His argument is basically that creativity can happen anywhere; it doesn’t matter where you are. You can take a space and you can play with it. It’s like a computer game, but it’s a game that has its end result in an artwork– and it’s a game which he enjoy playing! It’s something that, if you are waiting for a friend to come and you are half an hour early, you can play this game. It can happen anywhere.

As with many of the pieces in the show, this work draws on the artist’s practice on the street, which raises questions about the complexities of curating graffiti/street art in a gallery context. Do you think this is still an issue?

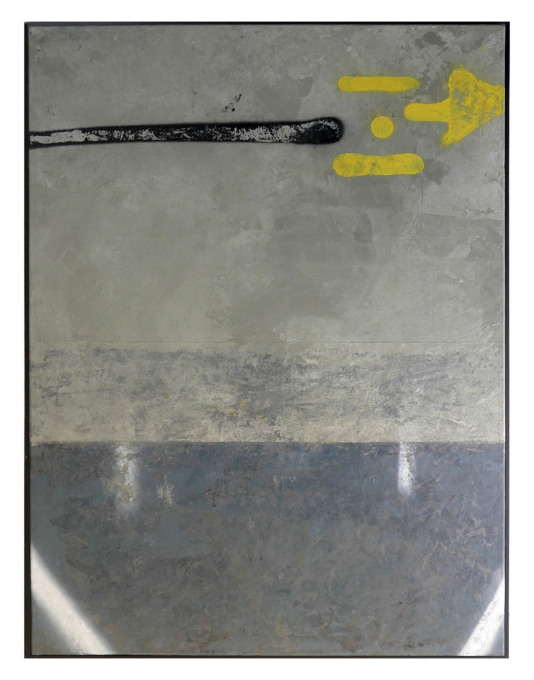

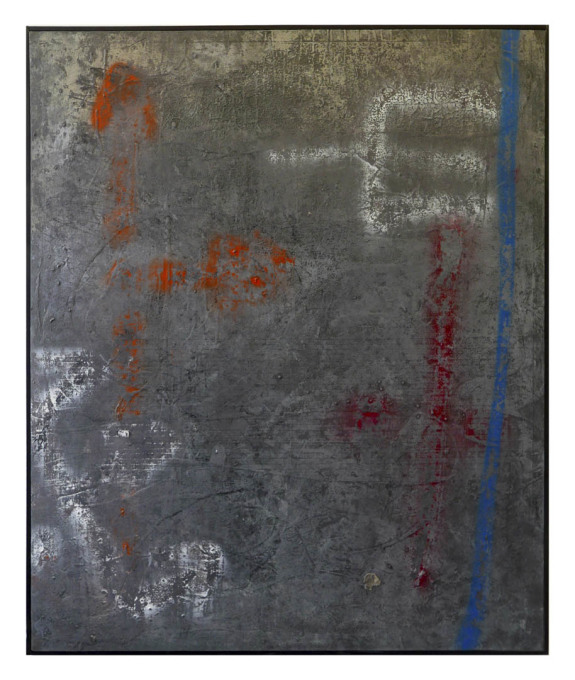

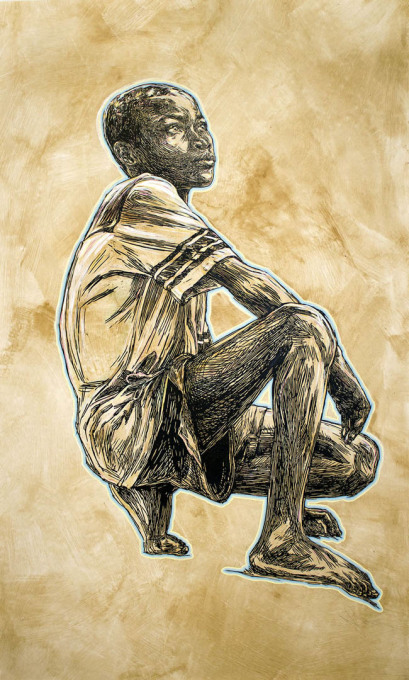

It’s something that we’re working on trying to express. The first thing to say is that all the artists in the show are almost all still practicing graffiti but they also have a studio practice. Some of them have been painting graffiti for over 20 years, so there is a deep history of them painting within the public sphere, but at the same time a studio is just another space for them to explore. I think it’s restrictive to think that a person who works in the public sphere can’t also work in a gallery exhibition dynamic as well. The work that we show in the exhibition is all “contemporary art” but it’s indelibly infected and inflected by their graffiti practice. You can’t understand one without the other.

Do you think the wider world of contemporary art is coming round to this more nuanced understanding of their work?

They’re still often dismissed for being this kind of trashy art because they get slammed with the name street art or graffiti. In my opinion this field is as strong as any other. But we need a new term for it because everyone is sick of this situation and I think without a new term it’s going to be difficult to get past it. Many artists are now trying to hide their graffiti background. Whereas ten years ago everyone was faking a graffiti background to get a gallery show, now people are actually hiding that background or trying to keep it separate from their studio fine art practice because it can actually have a negative effect on their career.

This is a very different type of negativity to how it was, say, 20 years ago right? The negativity now is not associated with crime and vandalism, but a grey area to do with contemporary art aesthetics…

In terms of the studio practice it’s more to do with just being considered a kind of trashy form of art. It’s looked down upon. Simple as that. It’s not seen to be as intellectually rigorous perhaps as a lot of other contemporary art. That’s the problem at the moment. It’s just considered trashy because in the auction setting and in the high gallery setting the work that is getting attention is at the trashier end – the easier to consume end of graffiti/street art.

Aside from A(by)P, are there other spaces exhibiting this kind of boundary pushing work in your opinion?

Places like Alice Gallery in Brussels are doing great work and working with great artists. Ruttkowski Gallery in Cologne as well. V1 in Copenhagen also do amazing work. V1 is definitely at the head end there. Like us, they believe it’s not just about street art or graffiti, but about an ethic which emerges from those practices. It’s kind of weird art that’s still very considered and high end but doesn’t sit comfortably in that contemporary art milieu – that’s what we are interested in.

Venturing Beyond: Graffiti and the Everyday Utopias of the Street

until May 2, 2016

Somerset House

Strand

London

WC2R 1LA