An exhibition exploring the design of children's play spaces, raises wider questions about the value of design in the urban realm, as well as ongoing issues of power and ownership in public space.

With Düsseldorf its usual glossy-self, not seeming to acknowledge any whiff of global recession – both on the street but also in its level of arts funding and quality of provision – it is rather a shock to enter the Schmela Haus, although it is very much a result of the latter: having re-opened as a gallery in 2009 as the third venue for the public art collection of North Rhine-Westphalia. But the architecture of the building itself breathes a rawer, tougher aesthetic, from a time nearer the austerity of post-war, deep in the chill of the Cold War. It was designed by Aldo van Eyck, and completed in 1971, as a commercial gallery for the influential art dealer Alfred Schmela, incorporating his own home too, an apartment which sits at the top of the three storey, two basement structure.

In a nice piece of programming, the current exhibition (of the now publicly-owned gallery), Das Kind, die Stadt und die Kunst, focuses on one famous aspect of van Eyck’s own practice: the design of children’s playgrounds, particularly those he built in Amsterdam, and shows this concurrently with work from two contemporary artists, Yto Barrada and Nils Norman, that also reflects on the spaces of children’s play.

This interesting combination of practitioners – loosely grouped through a theme – works because the work of each is exhibited in a separate gallery spread over different floors, without any overly-curated cross-currents needing to be cued across a single gallery.

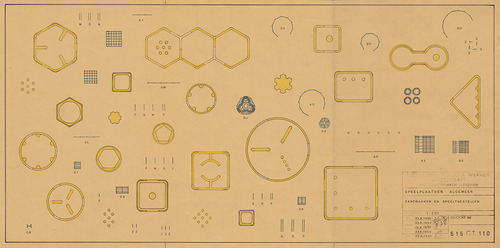

At the core of the exhibition are van Eyck’s designs for playgrounds, represented by archive material in the basement gallery. This documents the 700 playgrounds he designed across Amsterdam: a mass-designation of public space specifically for kids that was revolutionary at the time of their construction.

For me, van Eyck has always been easier to love for his ideas and ideals than for his schemes and buildings. His designs and spaces always seem, given the warmth of his ideas, somewhat barren. The Schmela House itself is a case in point, containing some extraordinary spatial moves, yet with a somewhat grim institutional feel in its texturing and detail, with bare unforgiving concrete-block walls even in the living spaces of the top-floor apartment. (It made me recall some of the classrooms of my youth: perhaps their bare unplastered rooms had actually been evidence of van Eyck’s influence, not education budget cuts?)

The design for his playgrounds too – presented in fascinating archive photographs and particularly beautiful drawings – exhibit this same spatial dexterity but heavy-handed reality. And whilst he was a founding member of Team 10, wanting to humanize architecture in reaction to the authoritarianism of Corbusian modernism, his interventions now look just as proscriptive. Some of the before-and-after photographs are telling: a pleasant alley-like street in Amsterdam, where you can imagine kids playing ball against a wall, seems to be interfered with, rather than transformed for the better, by a sand-pit, which seems to serve to both ghetto-ize play and create a near useless urban space when children aren’t around.

Upstairs on the ground floor, the British artist Nils Norman shows a new installation, tailored to the gallery space: a display structure-cum-reference library-cum-series of children’s play spaces. Its series of cuboid forms are punctured with circular cut-outs and cushions, purposefully echoing the rounded forms of van Eyck, and visually they lead out to two circular sandpits in the backyard. It doesn’t look much different from a regular children’s play structure (and indeed the aim is to donate it to a school afterwards), but it is scattered with books from Norman’s own archive and his research into play spaces. But again in the absence of any adults hunkering down in one of the small cubes to read-up on play-spaces (an unlikely proposition anyway given their size) – let alone any kids rushing around and through the structure – the whole installation has a rather forlorn aspect.

Meanwhile, in the top gallery, Barrada’s work presented in a series of films and a floor-based piece looking like giant children’s building blocks – although this time not designed to be played with – cross-references van Eyck less directly. Her films of Tangier juxtapose images of children playing in a semi-derelict playground with the booming new developments happening in the city. Across the gallery floor, huge children’s building-block letters spell out the name “Lyautey”, after the French colonial leader Hubert Lyautey whose policies of European-style modernization intervened across Moroccan art, agriculture and architecture. As Barrada puts it: “For him, Morocco was a laboratory of the modern, a playground.” The sub-text of a country patronized and exploited, yet also given material advantages through being the subject of an experiment outside its own people’s control, is left hanging, set against images of the new forces driving development now: globalized economics, with no clear leader, except money, in charge.

The politics that are slightly over-egged in Barrada's work are less explicit, but ever-present across all the work in the exhibition. Questions of the power of authority – the state, the city, the adult world – set against individual freedom and the gestures of play, as well as the dangers inherent in play itself – of either under- or over- regulation – infuse the exhibition, nicely raising wider questions on design's real value in the urban realm, and of ongoing issues of power and ownership in public space.

Das Kind, die Stadt und die Kunst

–

Aldo van Eyck, Nils Norman, Yto Barrada

April 19 – September 15, 2013

Schmela Haus

Mutter-Ey-Straße 3

40213 Düsseldorf

Germany