-

Magazine No. 02

Venice & the Common Ground

-

No. 02 - Venice & the Common Ground

-

page 02

Cover

Venice & the Common Ground

-

page 03

Editorial

-

page 04 - 05

Chapter No. 01: Common Ground

David Chipperfield on his curatorial concept

-

page 06 - 20

Excavating the Common Ground

Our highlights from the two main exhibitions

-

page 21 - 28

Architecture observes itself

This biennale misses social and political topics – and voices from outside Europe

-

page 29 - 30

Chapter No. 02: Golden Lions

-

page 31 - 38

Stimulators and Moderators

Jury member Kristin Feireiss about the Golden Lion awards

-

page 39 - 41

Chapter No. 03: Must-see Suggestions

-

page 42 - 46

Old Buildings New Life

On the theme of conversion and renewal across the biennale

-

page 47 - 49

Architecture, with love

Greece and Spain address economic turmoil

-

page 50

And now the ensemble!!!

The melancholy of the Swiss Pavilion

-

page 51 - 53

The way of enthusiasts

An exhibition that’s worth the boat ride

-

page 54 - 59

Dark Side Club 2012

The dark side of debate

-

page 60

Next

Manuelle Gautrand

-

-

Inside uncube No.2 you’ll find our selections from the 13th Architecture Biennale in Venice. We’ve searched high and low for the best pavilions, exhibitions, and events, and the most imaginative and innovative reactions to the rich but tricky theme of Common Ground chosen by this year’s director David Chipperfield.

This issue is designed to either whet your appetite as you pack your bags – or, time or budget restrictions considered, give you a good overview of the biennale from the comfort of your own device.

EITHER WAY: BON VOYAGE!![lion_text.png]()

Cover Photo: Torsten Seidel

-

![]()

Chapter No. 01

Common Ground

-

WHAT IS »COMMON GROUND«?

David Chipperfield on his curatorial concept

![]()

-

Excavating

the Common

GroundOur highlights

from the two

main exhibitions -

![]()

The Arsenale exhibition opens with photographs of Thomas Struth reflecting on his memories and experiences of Germany’s urban landscape. The complete quietness of these pictures contrasts perfectly with the next room… (Photos: Francesco Galli / Biennale di Venezia)

-

![]()

![]()

… a black box, where Norman Foster’s Gateway creates a speedy circulating mass of projected text and images. On the floor in black and white, the names of important figures from the history of architecture flicker across visitors’ faces and bodies as they circle the room watching images and listening to the sounds of public spaces from around the world. (Photos: Francesco Galli / Biennale di Venezia, Benedikt Hotze)

-

Museum of Copying by FAT Architects (with San Rocco and Ines Weizman) has a catchy slogan: “Hail to the Copy!” In front of their cut-up version of Palladio’s Villa Rotunda, possibly the most copied building in the world, we met with FAT’s Sam Jacob to let him explain his interest in copying and its relevance in architecture. (Photo: Torsten Seidel)

![]()

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

Because of its controversial contradictions, this was the funniest room: FAT’s Museum of Copying shares a space with Cino Zucchi’s Copycat and Hans Kollhoff’s Tektonik – Morphologie städtischer Fassaden. The cheap copy of the Villa Rotunda connects to Zucchi’s collections of pictures, models, insects, and Indian Chapati rolling pins and to Kollhoff’s collection of facades and models full of historical references – or repetitions? An outraged Peter Cook called Kollhoff’s installation an “affront to all that is liberal, sensitive, humane, progressive, delightful, or responsive.” (Photos: Benedikt Hotze, Florian Heilmeyer, Torsten Seidel)

-

Is this a highlight? We still aren’t sure. But even if Zaha’s architecture seems to be nothing more than a formal experiment, we must admit that Arum has a certain attractiveness in combination with her own sleek white spaceships floating through the room, the strange metal tower of shimmering silver, and the collection of great construction studies by Heinz Isler, Felix Candela, and Frei Otto. (Photo: Sergio Pirrone)

-

Photo: Iwan Baan

-

Our favorite piece (and well-deserved Golden Lion winner) is Urban-Think Tank, Justin McGuirk, and Iwan Baan’s: Torre David/Gran Horizonte. The investigation and documentation of an abandoned high-rise-turned-squat in Caracas is presented as an informal street café Latin American-style, creating a true Common Ground inside the Arsenale with cold beer and a Latin hip-hop soundtrack. Watch our video interview with Urban-Think Tank’s founding directors Alfredo Brillembourg and Hubert Klumpner. (Photo: Iwan Baan)

![]()

![]()

-

![]()

![]()

The hectic pulse of the main exhibition suddenly stops. Enchanted visitors, mostly smiling, wander slowly through Álvaro Siza Vieira’s structure, the folding and unfolding spaces of which integrate beautifully into the little garden at the end of the Arsenale, including the garden’s impressive old trees, providing framed views here and there. Both a tribute to the landscape and to the city, this structure is a magnificent, poetic point of meditation and a celebration of what architecture can do with space. (Photos: Francesco Galli / Biennale di Venezia)

-

![]()

Airports, once touted as “non-places,” figure largely in this installation by Peter Fischli and David Weiss. The duo has been documenting these places of transit since the 1980s. Read through small details such as ground vehicle license plates or country/language specific signage, the photos reveal the specificity of these macro spaces through minute details. The photos are projected in a looped sequence, and airline drink trolleys figured in white provide a surreal physical reality. (Photo: Francesco Galli / Biennale di Venezia)

Peter Eisenman Architects with Dogma, Yale University, and Jeffrey Kipnis: Piranesi Variations. Four teams have taken Giovanni Piranesi’s famous and completely fictitious Campo Marzia drawing of ancient Rome as a starting point to develop new visions. Watch our video to hear why Eisenman thinks that dealing with Piranesi’s historical fiction is still relevant.

![]()

-

OMA’s Public Works presents architecture designed by civil servants in five European countries, such as the Greater London City Council, the Wibauthuis in Amsterdam, and the St. Agnes Church in Berlin. During the 1960s and 1970s a number of left-leaning governments established large public works departments to reengineer urban spaces. These public buildings are mostly lesser known, but arguably important for the legacy of architecture. In the age of the starchitect and the disillusionment of ideology, OMA reminds us that we don’t have to travel so far back to see powerful and inspiring architecture that served something as grand an idea as serving the greater good. (Photo: Torsten Seidel)

-

![]()

Crimson Architectural Historians’ The Banality of Good examined New Towns – entire new cities and urban environments built using massive-scale master-planning efforts. Crimson identified continuity in formula. Shifts in ideologies, demographics, and political systems seem to be easily incorporated into the new town model. Triptych collages present the context, ideological imagery, and progenitors for a collection of New Towns from the past six decades. (Photos: Francesco Galli / Biennale di Venezia)

-

![]()

![]()

For Swiss office Diener & Diener’s Common Pavilions, photographer Gabriele Basilico and a group of authors have been invited to take a fresh look at the 30 national pavilions in the Giardini. Rarely do visitors focus on the buildings that house the presentations themselves – but as Diener & Diener demonstrate, the pavilions are impressive and historically-important structures in their own right. This contribution will be published as a book later this year. (Photos: Benedikt Hotze)

-

Elemental: The Magnet and the Bomb. The Chilean office Elemental shows two current projects in a beautiful and carefully-considered projection and installation. We met one of Elemental’s principals, Alejandro Aravena, to let him explain the extreme conditions of these projects: One town hit by a tsunami, the other by what he calls a “social tsunami.” (Photo: Benedikt Hotze)

![]()

-

![]()

Peter Eisenman stands before The Piranesi Variations, his contribution to the main exhibition, gesturing energetically. “Architects cannot save the world. Architects cannot save anything. They should concentrate on what they can do, and that is building.” Does this mean it’s back to the drawing board? Enough already with the social, ecological, and political debates that have so engaged the world of architecture in recent times?

This reticent attitude certainly seems to apply to many of the contributions on view in David Chipperfield’s Common Ground exhibition. In Venice this year, architecture is presented foremost as the art of building – it deals, above all, with itself. References to architectural history are ubiquitous, from Palladio to Frei Otto, but the present moment and bold visions of the future are noticeably absent – unless Zaha Hadid’s spaceship-like explorations of form still count as futuristic. It has been quite a while since the Venice Biennale has focusedARCHITECTURE

OBSERVES

ITSELFDavid Chipperfield’s Biennale misses social and political topics – and voices from outside Europe

Text by Florian Heilmeyer

-

![]()

»In Venice this year, architecture is presented foremost as the art of building – it deals, above all, with itself.«

so intensively on forms and models. They fill hall after hall, most of them concentrated on the building as a singular object. Seldom are their contexts and inhabitants shown. Instead, attention is turned to quality of detail and material. “Form over context” applies to Hans Kollhoff ’s studies in style and façade as much as Zaha Hadid’s construction experiments, even though their positions are diametrically opposed.

Not that there aren’t positive moments. Luckily, Chipperfield has dared to present a range of architectural positions that is as broad as possible. Never before has there been an exhibition where Hadid and Moussavi were presented in one place together with Kollhoff and Lampugnani. “They all have important and very influential positions that should not be left out,” says Chipperfield, thereby confirming his liberal invitation policy. Indeed, these extreme differences are what make the exhibition a thoroughly entertaining tour that warrants a closerlook in many instances: Olgiati’s large-format Pictogram table, the Museum of Copying by FAT Architects, Norman Foster’s wild video installation Gateway, and Alvaro Siza’s wonderful pavilion sculpture – which demonstrates the poetry that can result from wall, space, color, and light by using only two angled walls, whose dark red color refers to the simple garden shed behind.

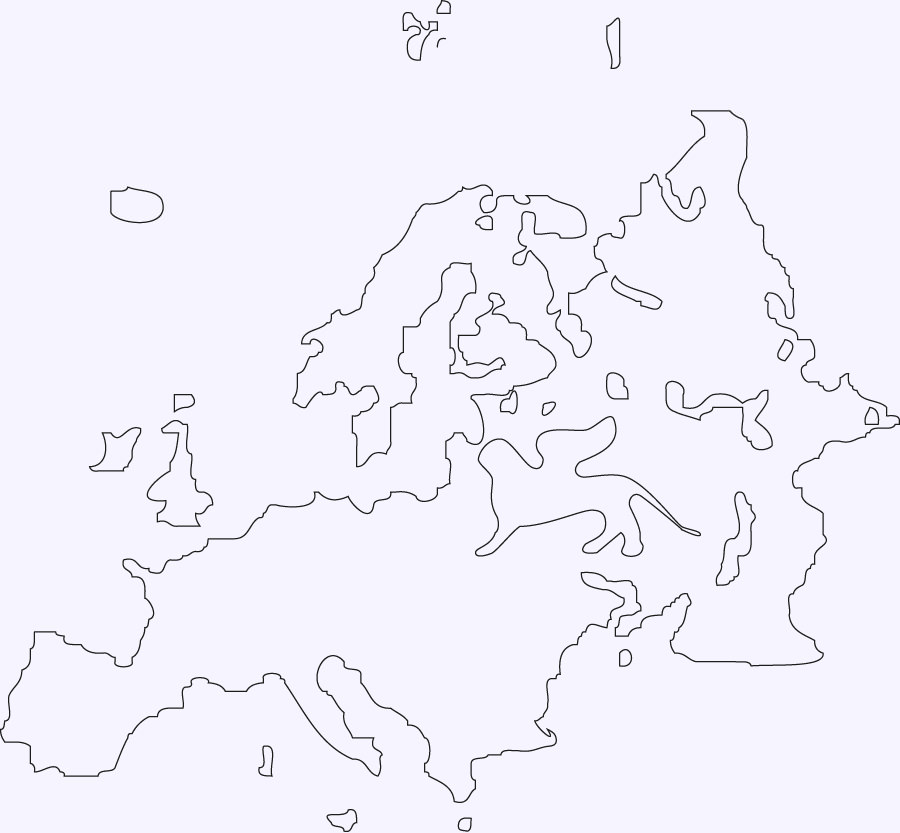

And yet, at some point disappointment sets in. Ultimately there is a lack of the radical – and there are no real surprises. Most contributions are harmless and/or predictable. Despite the presence of good and very good architecture, what is missing are themes that can be discussed with passion and conviction. This might be because Chipperfield’s Biennale is more Eurocentric than perhaps all others before it: of the 69 invited architects and artists, 52 (!) are from Europe, and many of them are from Switzerland and England. Asia, Africa, and Latin America are virtually unrepresented. -

![]()

Without doubt, this is partly a result of the unacceptably brief amount of time that Chipperfield had, following the 2011 political turbulence in Italy, to prepare an exhibition of this scale. He was only officially confirmed as director in January – seven months before the opening – which is reason enough to allay much heavy-handed criticism of the occasional curatorial shortcoming. Nevertheless, since more than a few of the national pavilions specifically focus on buildings as such, one might begin to wonder if (European) architecture today finds itself in a moment of self-reflexivity and therefore of helplessness. Yet this could also be viewed positively: we might be on the brink of profound shifts in the architectural discourse. Something genuinely new might arise. But it seems this change will not be coming from Europe.

»Chipperfield’s Biennale is more Eurocentric than perhaps all others before it.«

-

Photo: Torsten Seidel

RE: COMMON GROUND

Reflections and reactions on the main exhibition

Andres Lepik (Professor for History of Architecture and Curatorial Studies, Director of the Architekturmuseum der TU München):

»The Biennale di Venezia has rapidly lost its relevance for architectural discourse over the last years. While Ricky Burdett succeeded in 2006 with setting up a general theme that was urgent and timely and at the same time found a convincing form of presentation, David Chipperfield just didn’t have enough time to work on a show that catches the important aspects of contemporary architecture. The title Common Ground is already too generic and there are too many starchitects invited who don’t care about the real needs of 99% of the world’s population. At least the Jury for the Golden Lion corrected the general tendency of this year’s biennale by honoring Toyo Ito’s and Urban-Think Tank’s contributions.«

![lion_text.png]()

![re_common_ground_gfx_01.png]()

Beatrice Galilee (London-based curator, writer, and critic, Chief Curator of the Lisbon Architecture Triennale 2013):

»While Common Ground is a curious and critical theme, offering refuge from the notion of the architect-author, the participants selected did not universally rise to this challenge. There were some warm, elegant, witty, and serious projects, but in my eyes they were the exception. The notion of the exhibition as a method of reflecting or proving architectural tropes feels dated – it should instead be challenging, useful, and productive.«![lion_text.png]()

![re_common_ground_gfx_02.png]()

-

Photo: Torsten Seidel

Pedro Gadanho (New York-based architect and writer, Curator of Contemporary Architecture at the Department of Architecture and Design, Museum of Modern Art):

»Some years ago, I heard people around me at the Venice Biennale saying they couldn’t find any architecture on show. At the time, I disagreed. There were plenty of interesting propositions around. And those probably had a surprise effect because they hadn’t yet been massively distributed by the web-based media. Now the biennale is faced with precisely that problem: when you have already seen everything online, it is difficult to create an impact with new ideas. Unlike at the art biennale – in which lots of new work is revealed for the first time, if not kept in secret to be unveiled at that very moment – strategies and forms of architecture display have to be re-thought in terms of what new orientations these large cultural events should take to compete with the speed and lack of reflection of online media. This being said, it was revealing that, though the biennale director is also an architect, there were so few new architectural propositions and positions around. The theme Common Ground had the effect of leading everybody to focus on context – and to forget how architecture can actually respond with innovation and responsibility to a given, shared context. Visual exercises like that of Norman Foster’s installation thus seemed like emptied-out TV shows that said nothing about how architecture must respond to our current imbalances. Other situations – small oases of meaningful and playful intent, such as the Urban-Think Tank installation – seemed to only reiterate what, in certain circles, has already been stated over and over throughout the last years. In general, it looked like we were at a standstill – which would be precisely what the biennale should be attempting to overcome.«![lion_text.png]()

-

Photo: Torsten Seidel

Peter Cachola Schmal (Frankfurt-based architect, writer and curator, and director of the Deutsches Architekturmuseum DAM):

»I was a little disappointed with Common Ground, as I was expecting David Chipperfield to adopt a broader view of the world. His firm is building and designing globally, so a more global list of invitees should have been possible. In the end, some of the participants really made up for any shortcomings though – and some of the highly criticized stars excelled: Zaha Hadid’s retro-argument (towards Heinz Isler and Felix Candela) was very professional and captivating, although for fans of structural engineering it may not have been entirely convincing. Both of Foster’s shows, the fast and furious film and the Hong Kong Shanghai Bank, were excellently made. Grafton’s contribution and homage to Paulo Mendes da Rocha was just wonderful – I would have given it the Golden Lion. And finally, Rem Koolhaas showed all of us curators that he is still the ultimate benchmark in terms of conceptual contributions. No wonder, rumor has it, that he will be the next General Commissioner of the Biennale. In that case he would have more than two years to prepare – and I am sure it would be a seminal show.«![lion_text.png]()

![re_common_ground_gfx_03.png]()

Louisa Hutton (Partner at Sauerbruch Hutton, Berlin):

»Of course the theme and the term Common Ground is rather elastic – which is fine given the size of the whole Biennale and the invariably brief time that is available to put it together. But what I find particularly inspirational are some of the collaborational, or let’s say mutually respective efforts. For example, the first room in the International Pavilion is where Grafton Architects from Ireland demonstrate their respect for Paulo Mendes da Rocha – what they are learning from his work and how this may translate when considering their own project in Peru. At the same time this particular contribution is also very beautifully installed – that is a positive way to begin the exhibition.«![lion_text.png]()

![re_common_ground_gfx_04.png]()

-

Photo: Torsten Seidel

Steven Holl (Architect, New York):

»Our common ground should be the globe, our earth. To invite nine Swiss architects to this biennale and only one from China is kind of strange to me...«![lion_text.png]()

![re_common_ground_gfx_05.png]()

![]()

-

![]()

CHAPTER NO. 02

GOLDEN LIONS

-

The jury of the biennale, composed of Wiel Arets (Netherlands), Kristin Feireiss (Germany), Robert A.M. Stern (USA), Benedetta Tagliabue (Italy), and Alan Yentob (Great Britain), decided upon two Golden Lions and one Silver Lion. Furthermore, the pavilions of the USA, Poland, and Russia received Honorable Mentions. The Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement is regularly announced a few weeks before the biennale starts – this year it was awarded to the great Álvaro Siza, and his masterly installation in the Giardini del Vergine demonstrated his excellence in a light-hearted way.

The Silver Lion for a Promising Practice was awarded to Grafton Architects (Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara) for “the conceptual and spatial qualities of the installation and the considerable potential shown in re-imagining the urban landscape.” The Golden Lion for the Best National Participation went to Toyo Ito’s exhibition Architecture. Possible Here? in the Japanese Pavilion, and the Golden Lion for the Best Contribution to the Common Ground exhibition was given to Torre David/Gran Horizonte by Urban-Think Tank, Justin McGuirk and Iwan Baan.

![lion_text.png]()

![]()

Toyo Ito

![]()

Urban-Think Tank, Justin McGuirk

and Iwan Baan![]()

Grafton Architects

-

![]()

STIMULATORS AND MODERATORS

Jury member Kristin Feireiss speaks about this year’s Golden Lion awards

Interview by Florian Heilmeyer

-

![]()

The Japanese Pavilion was honored for its storytelling qualities and human engagement. (Photo: Benedikt Hotze)

As soon as she returned to Berlin from the opening in Venice, we met with an enthusiastic and lively Kristin Feireiss to ask about the jury’s criteria for the Golden Lions – and whether their selection can be interpreted as a statement about the importance of social engagement in architecture today.

What were your jury decisions based upon? How did you weigh such varied contributions against each other?The criteria were completely up to us. During our first meeting it became clear that besides the content and theme of each project, the form of presentation should be evaluated and play an important role in the jury’s selection. Many people who visit the biennale are neither students of architecture nor experts, but normal people who rarely visit an exhibition on architecture. Therefore it was important to us to evaluate each spatial experience insofar as it is able to draw the visitor into the content – or make the topic more understandable. Of course the spatial experience must also relate closely to the topic; a spectacle without any link to its content would have had no chance for a Golden Lion.

![]()

Kristin Feireiss, member of the 2012 Golden Lion Jury. (Photo: Courtesy AEDES)

»The architect is not the single genius anymore, the problem solver with the big master plan.«

-

Did you discuss every contribution?The five of us spent three and a half days visiting all contributions in the Arsenale, the Giardini, and those spread throughout the city. During these intense days we were in continuous conversation – but when we were talking about the awards in the end, only the contributions that at least one of us found relevant enough were discussed. Though our discussions were pretty lively, in the end we agreed upon the winners 100 percent.

The jury’s statement says that you were explicitly convinced by the “storytelling” of the Japanese Pavilion. Could you explain this?First of all, the project itself is impressive and to present it as Japan’s contribution is really bold. Ito doesn’t present something finished and perfect but instead an ongoing process. A community, moderated by an architect, tries to develop a step-by-step strategy after a natural catastrophe. But despite the huge panorama that covers the walls, the pavilion doesn’t make a spectacle out of this disaster – it is simply a fact that the people have to deal with. For instance, the impressive videos are shown on very small screens, so you really have to discover them. To me, the tree trunks in the space were highly aesthetic – in a good sense. And it really touched me that these trunks reappear in the videos where you see them lying around everywhere along the coast after the tsunami.![]()

The Golden Lion winning Torre David was an exhibition-cum-pop-up restaurant (Photo: Iwan Baan)

![]()

Processes of post-tsunami reconstruction are presented in the Japanese Pavilion. (Photo: Benedikt Hotze)

-

The Torre David as presented by Urban-Think Tank, Justin McGuirk, and Iwan Baan was honored for its social and architectural relevance. (Photo: Iwan Baan)

-

»Progress and development is more and more about small steps instead of big landmark buildings.«

And the Torre David…?

This project is a different story. Here, the process was informal and self-organized. The architects arrived later. But then they acted as advisors on how to improve the living conditions in this 45-story building without any infrastructure. There was no electricity, no water, no façade, no elevators. To look at these kinds of developments is important, but to react to them in the right way is even more important. The city officials wanted to tear the entire building down, and they still want to do so. But with 3,000 people living there that is of course difficult – and with the publicity of the Golden Lion it seems to get even more difficult now. To present this project here in Venice was obviously very difficult, too, as Venezuela did not want to present this “vertical slum” as something typical of Caracas or Latin America. So with all this in mind, the lively, noisy, and – most of all – humorous presentation of the project as a Latin American restaurant in the Arsenale is brilliant. And it was not just for show, it was really trying to bring an authentic piece of an informal structure of Caracas to Venice.

In your explanations, you often point out the winning exhibitions’ connections with David Chipperfield’s general theme, Common Ground. How did you interpret the broad topic in regards to the contributions you’ve chosen?

Common Ground is a really difficult topic, but I think that in general the exhibitions at the Arsenale and the Central Pavilion succeeded in dealing with it. Of course there are always single pieces that could have been left out, but most of the participants found that the role of architects and planners is changing. The architect is not the single genius anymore, the problem solver with the big master plan. Today architects have to act more and more as moderators and stimulators of urban, social, and political processes. They have to form alliances with other actors, and build groups with shared interests in order to reach their goals. Progress and development is more and more about small steps instead of big landmark buildings. To me, these are the most important ideas of Common Ground. I think that changing the picture of the architect is incredibly important, as it can illuminate new fields of action –

-

especially in a big exhibition like in Venice that tends to focus on the international heroes of architecture, relatively few of whom are participating this year in comparison to previous years.

It seems that overall there are two major points of critique regarding Chipperfield’s exhibition. The first is that he invited mostly architects from Europe, while voices and positions from Latin America, Asia, and Africa are almost completely missing. The second is that social and political topics are hard to find. That’s why I was personally so happy with the jury’s decisions – both Japan’s and Urban-Think Tank’s contributions focus explicitly on social and political topics. With these choices you have somewhat counteracted the two biggest deficiencies of Chipperfield’s exhibition. Can this be read as a statement of the jury?

Maybe. As a jury we never discussed forming our own focus so much; we have chosen the projects that we found the most convincing in showing new strategies and important developments in architecture. I found it

![]()

![]()

The Torre David was one of the few parts of Common Ground from outside of the European context. (Photos: Iwan Baan)

-

![]()

particularly interesting how easily we agreed as a jury in choosing these projects. The most relevant question seems to be: how can the architect try to approach contemporary challenges and urban problems? This question is not only relevant for developing countries but also in Europe and North America. That’s why we also found the pavilion of the USA interesting, since it took a careful look at small-scale interventions, most of which were not initiated by planners or institutions but by groups of citizens. Very basically, architects have to think about the current living conditions of people – and how to improve them, even if just a little bit. That’s the task of architecture.

Isn’t it then even more striking that the most innovative and interesting contributions seem to come from Asia and Latin America? Walking around the biennale, I got the impression that Europe refers mostly to itself, and its architecture is preoccupied with its own European history. And I’m not only talking about Hans Kollhoff and Vittorio Lampugnani. Might this impression have to do with the choice of participants by David Chipperfield, or was it rather the result of the question he posed?It’s important to keep in mind that Chipperfield is a sophisticated, intellectual, and culturally-interested man, but he is also an architect who builds. So it’s not too astonishing that he puts building itself in the focus of his exhibition. But you are right, this biennale presents mainly European architects and European positions. Other continents that are extremely important to the discourse about any urban topic like Asia, Africa, and Latin America are completely under-represented and it would be an important question to ask why that is. But this is a question that only David Chipperfield could answer.![lion_text.png]()

-

CHAPTER NO. 03

MUST-SEE

SUGGESTIONS![]()

-

GUERILLA

URBANISMFrom ad-hoc to DIY in the US Pavilion

Text by Jessica Bridger

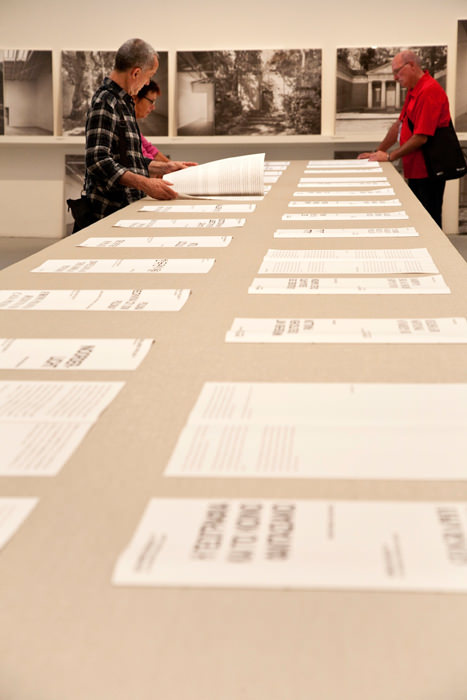

The US Pavilion’s curator Cathy Lang Ho took the theme Common Ground to heart, inviting 127 participants to exhibit, display, or otherwise engage with the biennale. Each one of the projects embraced something that architects have been developing strongly in the USA over the past few years: the DIY, the ad-hoc, along with vernacular and community-centered actions. These elements don’t always result in architecture in the proper sense, but all engage spatial issues in a broad way. Banners designed by M-A-D studio used color-coded bars to quantify the themes and issues in each project information (blue), accessibility (orange), community (pink), economy (light green), sustainability (dark green), and pleasure (blue), with projects and actions displayed on the reverse side, all selectable by theme using a system of pulleys on the pavilion walls. A complimentary program of events will continue throughout the Biennale. (Photo: Benedikt Hotze)

![flag_usa.png]()

-

REDUCE

REUSE

RECYCLEGermany’s Pavilion re-works the existing

Text by Rob Wilson

The abandoned-fairground look of old benches with peeling paint, and a cheesy light-bulb arrow pointing around the corner that redirects visitors to the former side entrance help to create a nice shift in the perception of the German Pavilion and its formal, classical language. This shift in perception is one step in the range of re-imaginings, conversions, and additions that are presented inside. With an interesting choice of projects and a simple, strong exhibition design by Konstantin Grcic, the main element and focus of the pavilion are Erica Overmeer’s stunning photographs. This presentation, curated by German architect Muck Petzet, serves to make a subject often seen akin to make-do-and-mend as sexy and stylish. But the clarity of the presentation is let down by the muddled thesaurus of terms used. The myriad of words – renewal, infill, subtraction, redesign, maintenance, behavior, recycling – ultimately only serve to confuse rather than clarify the message of an otherwise inspired pavilion. (Photo: Thomas Spier)

![flag_germany.png]()

-

![]()

OLD BUILDINGS,

NEW LIFEOn the theme of conversion and renewal across the biennale

Text by Rob Wilson

(Photo: Thomas Spier)

-

The renewal and re-use theme of the German Pavilion was only the most explicit and thorough exploration of a topic that otherwise seemed to appear as a running riff throughout the biennale, not surprising perhaps in a world in ecological and economic crisis (although neither fact seemed to cause much of a ripple across the placid face of Chipperfield’s Biennale).

The concept was picked up in quite different forms and presentations than in Grcic’s clear aestheticized design for the Germans. For example, the Netherlands Pavilion was titled Re-Set, appearing at first to add yet another “R”-word to the extensive but slightly confused lexicon of terms that the Germans used to explain different degrees of building renovation. But for the Dutch, it was the pavilion building itself that was the focus for ideas in the re-purposing of space, or “the ability of architecture to start over,” as the press release put it.

The interior of the Dutch Pavilion was gently animated and manipulated by a giant curtain hanging from a rail that snaked and doubled-back across the ceiling like a giant Scalextric track. This curtain moved fitfully across and around the space, breaking up and dividing it, and was formed of pink and black fabrics, ranging from gossamer-thin netting to velveteen, allowing for varying degrees of light and visibility. The installation’s intention![]()

Inside Outside/Petra Blaisse, Re-set, Dutch Pavilion 2012. (Photo: Torsten Seidel)

-

![]()

Herzog & de Meuron, Elbphilharmonie – The construction site as a common ground of diverging interests, 2012. (Photo: Francesco Galli / Biennale di Venezia)

to “reveal the hidden potential a vacant building has to offer” seemed to divide opinion, variously judged as poetic and contemplative or facile and dumb.

Elsewhere, there were several archival retellings of well-known cause-célèbres in the re-purposing of chunks of city or key buildings. At the Arsenale, German architect Mark Randel (of David Chipperfield’s office) revisited the history of Tempelhof Airport in Berlin by presenting the wide-ranging plans for re-use or reinvention that followed its closure in 2008. In an adjacent display Herzog & de Meuron presented the media storm of newspaper headlines that has surrounded their Elbphilharmonie project in Hamburg, a concert hall growing out of an old warehouse in the city’s docks, a project that has been on hold since June due to the rolling dispute between city council, architects, and contractors – and their lack of common ground.

The Estonian Pavilion, How Long is the Life of a Building, presents what is described as a “visual poem” on the Linnahall Concert Hall, completed for the Tallinn sailing regatta and one of -

the signature buildings of the 1980 Moscow Olympics, a building which is now almost abandoned except as a training ground for narcotics police and their dogs. The situation is chronicled in an elegiac film of the dripping taps and echoing spaces of the near-empty building, which elegantly tells the story of lack of interest and imagination towards re-use of this building.

Many of these projects are put in perspective by Urban-Think Tank’s powerful documentation and staging of the squatting and transformation by slum dwellers of a high-rise in Caracas. It seems that in Latin America when it comes to re-use, stuff just happens whether you plan for it or not: there’s no sitting around. And this same energy infuses the Mexican Pavilion, which puts its money where its mouth is in terms of renovation. The Mexican Government is cooperating with Venice authorities to restore the derelict Church of San Lorenzo for future use as the Mexican Pavilion. For now, there is a simple but well-made exhibition on a series of significant cultural and arts buildings in Mexico, many of which reuse or convert existing buildings – a library from a tobacco factory, an art gallery from a sawmill.

Whether speculative, projected, or realized, these strategies for re-use come together to form a theme that can only grow at future biennales.

![lion_text.png]()

![]()

![]()

Culture under Construction, 2012, The temporary Mexican Pavilion outside the derelict Church of San Lorenzo. (Photos: Thomas Spier)

-

CULTURE UNDER

CONSTRUCTIONMexico’s church pavilion

Text by Rob Wilson

Off a small campo in the Castello district, the impressive but derelict Church of San Lorenzo is Mexico’s new pavilion, its use over the next nine years was granted in return for funding the church’s restoration. While the restoration has not yet happened, and the spectacular interior can still only be viewed from the doorway, in front of the church a highly-coloured hoarding provides the setting for the temporary Mexican Pavilion, containing the exhibition Culture Under Construction. In a simple and clear display, the exhibition details 13 recent cultural and artistic projects in Mexico, including libraries, arts centres, and botanical gardens, many of the them re-utilizing existing buildings – and making a powerful link with the future rehabilitation of the church. (Photo: Thomas Spier)

![flag_mexico.png]()

-

Photo: Francesco Galli / Biennale di Venezia

ARCHITECTURE,

WITH LOVEGreece and Spain address economic turmoil

Text by Jessica Bridger -

Not everyone is partying like a baroque king as world economies struggle with gasping last breaths. Some of the superstars of the Eurozone crisis – Greece and Spain – contributed a bit of a lament for lost chances, cancelled projects, and stalled dreams to the biennale. The relentless and continued uncertainty and (yes) failure that financial upheaval has brought to architecture is obviously profound.

An outstanding representation of these simple facts that are astoundingly absent from most of the biennale is Spain Mon Amour, curated by Luis Fernandez Galiano. His installation, as part of the main exhibition, gathers 15 projects from the better days of the boom times by five renowned Spanish offices (Francisco Mangado, Nieto Sobejano, Mansilla + Tuñón, Paredes Pedrosa, and RCR), and places them in the hands of angels. Literally. The offices paid 200 Spanish architecture students, dressed as angels, lovingly present the projects personally to visitors. These students almost certainly will have to face economic instability in their future, so this act is doubly cutting.

![]()

In Spain Mon Amour, Spanish architecture students in costume presented models of projects completed before the financial crisis decimated domestic architecture and construction industries. (Photo: Francesco Galli / Biennale di Venezia)

-

With equally matched passion, the Greek Pavilion is also a requiem for architecture-related dreams killed by economic instability. But it is also hopeful. This hope is displayed in projective dreams, visions, and interventions for one of the cities most profoundly affected by the financial instability: Athens. Two complimentary subjects ground the pavilion: the examination of historical and current conditions in the typical Athenian apartment block, the polykatoikia, and the fraught issues surrounding the use of public space in the city. In a small but moving gesture, decaARCHITECTURE created tiny vignettes of the bedrooms of real inhabitants from across Athens’s socioeconomic spectrum. From the largest and most positive to the small and mundanely melancholy, the Greek Pavilion charts the current state of architecture as a serious, important discipline that is part of a larger context.

![lion_text.png]()

![]()

Tiny voyeuristic views into the lives of Athenians put an intimate spin on a large-scale problem. (Photo: Jessica Bridger)

![]()

A pastiche of public space and private lives figured large in the Greek Pavilion, where economic crisis and architecture came together. (Photo: Torsten Seidel)

-

AND NOW THE ENSEMBLE!!!

The melancholy of the Swiss Pavilion

Text by Rob Wilson

Venice and melancholy are good bedfellows, but usually only when the mists of autumn come. However, while hanging around the Swiss Pavilion during the opening days of the Biennale, I caught myself humming the tune of Lana del Rey’s Summertime Sadness. The pavilion is curated by the master of melancholic atmosphere, Miroslav Šik, who studied under Aldo Rossi in Zurich, and his work has always echoed some of the De Chirico–esque sensibility of Rossi’s, seeming to hark back to some timeless Ur-past of the European city. In the near empty main gallery, Šik has wrapped around immense monochrome images of both his own work and that of Knapkiewicz & Fickert and Miller & Maranta, the two practices he asked to collaborate with him. These huge photographs developed directly on the walls have the quality of drawings, and the leitmotif seems to be of empty benches facing onto people-less places – relating in atmosphere to Šik‘s early drawings designed to represent the city specifically at 7:00 AM just after dawn. (Photo, background: Benedikt Hotze)

![flag_swiss.png]()

![]()

Portrait of Miroslav Šik. (Photo: Torsten Seidel)

-

THE WAY OF ENTHUSIASTS

An exhibition worth the boat ride

Text by Elvia Wilk

Urban Fauna Lab’s installation in the Casa dei Tre Oci includes an imported window that obscures the building’s lovely architectural features, as well as a laboratory table with a collection of materials for urban experiments. Urban Fauna Lab (Alexey Buldakov, Anastasia Potemkina, Ekaterina Zavialova), Expansive Species of MELZ, 2012. (Photo: ©Courtesy Yuri Palmin and V-A-C Foundation)

-

In the Giardini, Russia makes a gigantic leap from past to future, fast-forwarding from the 1960s Soviet Union directly into tomorrow. Across the water on the island of Giudecca, an art exhibition pauses in Russia’s present, creating a bridge between Soviet history and Russia today. In contrast to the pavilion’s enthusiastic presentation of a governmental initiative, the aptly-titled exhibition The Way of Enthusiasts provides a moment for critical reflection upon the history of Soviet architecture through the lens of Russian art.

Focusing partly on artistic works produced during or immediately following the collapse of Russia’s mid-century grand-scale social housing projects, the exhibition also incorporates contemporary artists investigating the remnants and echoes of the period today. The show’s title is taken from a Moscow avenue (“Shosse Entuziatov”), a nineteenth-century connecting route between the city center and Siberian zones of exile and imprisonment. Optimistically re-named in the 1920s, the street’s moniker is indicative of an era of gusto for the future and a glorification of the past – highlighting the rupture between Soviet public housing schemes and their actualization.

![]()

The young artists Arseny Zhilyaev installed a (usable!) soviet-style launderette, commenting on enforced shared use of amenities and lack of private spaces during the communist era. Laundry, 2012. (Photo: Courtesy Yuri Palmin and V-A-C Foundation, 2012)

![]()

The Gnezdo Group worked together between 1975 and 1979, staging protests and fostering political discussion in Moscow’s underground. Gnezdo Group, Demonstration: Art into Masses. Moscow, 1978. (Photo: Courtesy V-A-C Foundation.)

-

![]()

![]()

Andrey Kuzkin. Ustal (Tired), Action documentation, 2008.

On the Russian Pavilion’s ground floor, viewers peep through magnifying holes in the wall to see images of Soviet communities built during the cold war for scientific research. On the floor above - pictured here - viewers receive iPads to access QR codes coating three blinding light-up disco rooms. The iPads display extensive architectural proposals for a scientific community of (Photo: Thomas Spier)

The three-floor exhibition is a spatially and topically expansive curatorial effort, and the artwork is presented in fluent interaction with the architecture: the stunning Casa dei Tre Oci palazzo, a Venice landmark built at the turn of the last century. Many works converse directly with the building – for instance, Urban Fauna Lab imported a dirty, scratched-up window to obscure one of the Casa’s three magnificent “eye” windows, commenting upon the lack of both beauty and transparency in many designs for social housing.

The Way of Enthusiasts is not only one of the biennale’s most appealing exhibitions to non-architect audiences, but also to a contemporary generation interested in curatorial tactics that can be borrowed and shared between disciplines. Exhibiting architecture is as much a presentation of models and plans as it is a communication of the intangible, inarticulable feelings communicated through space. Enthusiasts is worth the vaporetto trip to Giudecca due to the wealth of information it presents – but moreover because of its emotional effectiveness, far beyond the didactic or pedagogical.

![lion_text.png]()

-

![Dark Side Club 2012]()

The Dark Side of Debate

Text by Norman Kietzmann

A truly spectacular location for the first night of the Dark Side Club on Saturday, August 24th: Palladio’s Villa Foscari from 1560, or “La Malcontenta.” (Photo: Torsten Seidel)

-

![]()

Winy Maas and Alison Crawshaw.

![]()

The discussion about South America included Gary Bates, Alejandro Aravena, Toshiko Mori, and Winy Maas at the dinner table. Giulia Foscari was a splendid host.

The Dark Side Club is the most exclusive and idiosyncratic event during the opening days of the Architecture Biennale. On three evenings, a group of 20 people meet for dinner followed by a salon. It’s not only the discussions that stretch long into the night that make it special. It’s the fact that for once, its prominent participants do not have to mince words. Press conferences are like cotton balls: cuddly soft. Everyone dutifully speaks their rehearsed sentences, offering brief answers to select questions, and then leaves smiling into the cameras. Architects at the biennale opening don’t act too differently from the actors at the subsequent film festival in Venice, presenting their newest screen projects. Everyone pretends to be part of a cheerful family. Should a critical word still happen to escape, it is simply smiled away, as if nothing happened.

It makes sense that the Dark Side Club has emerged during the past three biennales as a corrective for the typical manicured presentations. The salon, hosted by architectural consultant Robert White, brings the protagonists of the day to the table. In the rooms of a timehonored palazzo, they dine, drink, and then

![]()

-

debate — all in a way that is casual, bold, and refreshingly un-academic.

Admittedly, the club has no decision-making power and can hardly reinvent the wheel in a space of two or three hours of discussion. But what happens here is an exchange among creators who meet on equal terms. Instead of having to promote themselves and their projects, they can throw out whatever is on their mind. Provoking and criticizing is allowed, without others leaving the table in offense. To structure the salon, each evening is moderated by a different “curator,” who selects and introduces the overarching theme and gets the discussion rolling.

The first evening of this year’s Dark Side Club took place on the Venetian mainland. The group met on a sweltering evening under the portico of Villa Foscari Malcontenta, the Palladio masterpiece in the south of Mestre, where Zaha Hadid presented her Aura installation in 2008. The evening was led by Gary Bates, who sees in South America’s raw material and energy resources the motor for an emerging “Golden Age” that could significantly influence urban planning. Discussion participants

![]()

Aaron Betsky deep in discussion.

![]()

Sunday evening in the back room of a restaurant close to San Marco.

![]()

-

![]()

Patrik Schumacher...

![]()

...and Bjarke Ingels.

included Alejandro Aravena (Elemental), Winy Maas (MVRDV), Toshiko Mori, Giulia Foscari, and Louis Becker (Henning Larsen).

The two following evenings were improvised. The owner of the palazzo panicked two days before the first salon and cancelled the reservation. Perhaps she suspected that the evenings could be long and loud. The club was suddenly without a location — not an easy situation to remedy during the opening days of the biennale, for which most palazzi are booked for exhibitions and events months in advance. So the club convened in a restaurant, resulting in a few charming intercultural discrepancies.

In northern countries it is customary after dining out with friends to order a bottle of wine and to continue the conversation, lingering at the table in the restaurant. In Italy, however, after the espresso it is really over. Then it’s off to bed. A casa. The motley group of architects in the back room of a restaurant not far from the Piazza San Marco indulging in after-hour wine and heated discussion, earned looks from the restaurant staff and owner as if a group of Martians had invaded their restaurant.

-

![]()

The third dinner was located in an almost informal setting in front of a small restaurant close to Rialto, overlooking the Grand Canal.

This second salon evening addressed the line between art and architecture and was moderated by Kjetil Thorsen (Snøhetta). In 2007, Thorsen designed the Serpentine Gallery pavilion together with Olafur Eliasson, who joined the salon a bit later that night. “It is impossible to separate work into an architecture part and an art part,” said Thorsen, explaining why more teams and fewer individuals should be given credit for a creation. With participants such as Patrik Schumacher, Bjarke Ingels, Aaron Betsky (director of the 2008 Biennale), and Archigram veteran Peter Cook, the debate enjoyed a steady dynamic, as they dismantled the notion of artistic and architectural genius.

The salon was held in a restaurant on the third evening as well. This time it was not a back room, but right on a piazza with a view of the Canal Grande not far from the Rialto Bridge. François Roche, Hernan Diaz Alonso, and Mathias del Campo wanted to explore the possibilities of “Toxic Sublimini” with a “public performance in film noir style.” But just as the discussion between Peter Noever, Patrik Schumacher, and Tom Kovac was getting underway, the evening came to an abrupt end.

![]()

-

Shortly after midnight, the restaurant owner suddenly found the whole thing a bit too colorful and announced that he would close in five minutes. To prove he was serious, he removed the wine glass from the hand of a bewildered François Roche without further ado and banished the club into the fledgling night.

![lion_text.png]()

![]()

Just after midnight, when the discussion got interesting, the restaurant decided to close its doors... even to starchitects like Francois Roche and Patrik Schumacher. (All photos: Torsten Seidel)

-

![]()

Manuel Gautrand. (Photo: Torsten Seidel)

NEXT

MANUELLE GAUTRAND, PARIS

We’ll be back with issue No. 03 in which we visit Manuelle Gautrand, superwoman of French architecture, in her Parisian office for a comprehensive portrait of her sensibilities and projects. Among an array of other pieces, Lucy Bullivant discusses how young UK architects are adapting their practices to new economic realities, and slovenian architect Bostjan Vuga visits our photo booth.

![]()

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Architectural interpretations accepted without reflection could obscure the search for signs of a true nature and a higher order.«

Louis Isadore Kahn

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents