-

Magazine No. 03

Manuelle Gautrand

-

No. 03 - Manuelle Gautrand

-

page 02

Manuelle Gautrand

-

page 03

Editorial

-

page 04

Master on Display

Louis Kahn -- The Power of Architecture

-

page 05 - 25

Constructing Architecture as Narrative Sculpture

A profile of Manuelle Gautrand Architecture

-

page 26 - 37

Folding Emotion into Architecture

Manuelle Gautrand on origami architecture and built emotions

-

page 39

Hypertopia

-

page 40 - 46

In the Photo Booth with...

Bostjan Vuga

-

page 47 - 63

New Arcadians

Economic gloom sees young UK architects get creative with their practices

-

page 64

Next

Concrete

-

-

Uncube's editors are Elvia Wilk, Florian Heilmeyer, Jessica Bridger, and Rob Wilson. Uncube is based in Berlin and is published by BauNetz, Germany's most-read online magazine covering architecture in a thoughtful way since 1996.

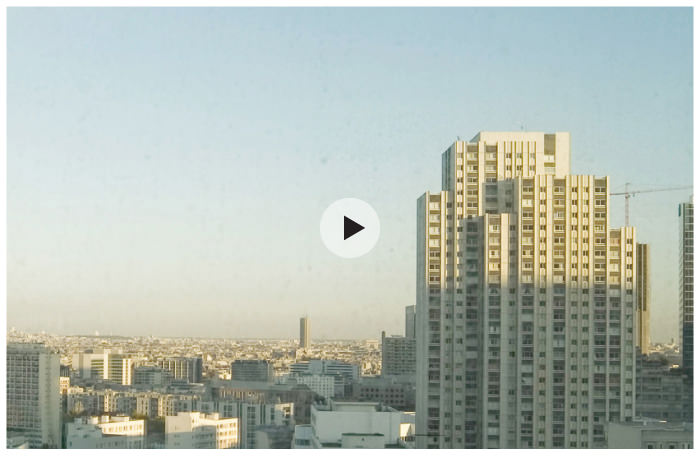

As the French architect Manuelle Gautrand remarks in this issue, skyscrapers are read differently depending from where we view them. Appreciated for their eye-catching tip from afar, they also need to work on a human scale up close.

In this issue of uncube, we’re zooming in from the big scale down to the small details of good architectural practice – in times of crisis or prosperity alike.

Enjoy,The Editors

![]()

-

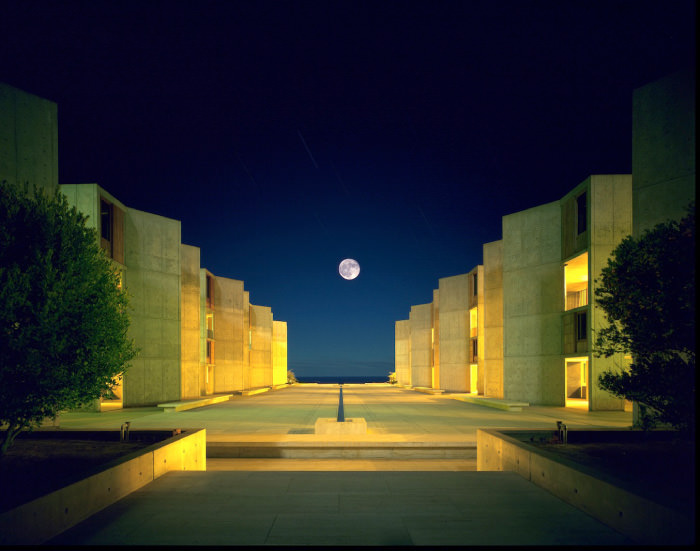

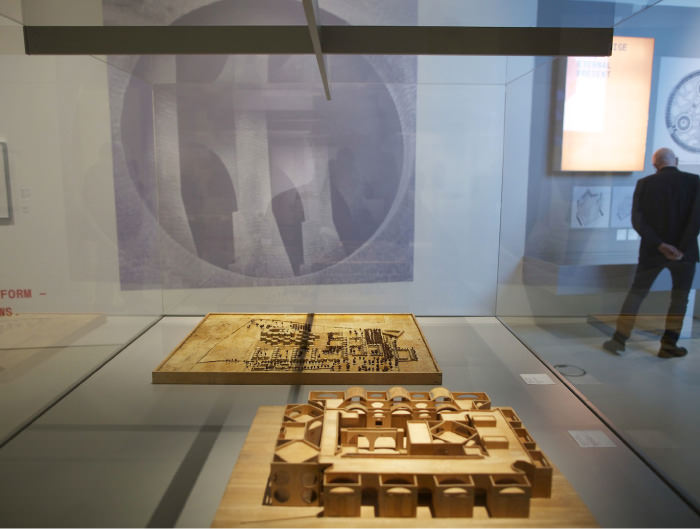

Exhibition: Louis Kahn — The Power of Architecture

Dates: 8 September 2012 – 6 January 2013

Location: The Netherlands Architecture Institute, Rotterdam

Curator: Stanislaus von Moos, Jochen Eisenbrand

Collaboration: Vitra Design Museum, Netherlands Architecture Institute, and the Architectural Archives of The University of Pennsylvania

![]()

![]()

Master on Display

Louis Kahn – The Power of Architecture

Text by Jessica Bridger

One of the final exhibitions at the Netherlands Architecture Institute before it becomes part of a three-part larger cultural entity in 2013 is, fittingly, a serious exhibition about one of the masters of modern architecture. Louis Kahn—The Power of Architecture is one of the biggest and most comprehensive shows to be launched about Louis Kahn since his untimely death in 1974. The show features sketches, drawings, photos, watercolors, videos, and models of Kahn’s buildings, both built and unbuilt. It also provides a timeline of key developments in Kahn’s life. Between the different forms of representation, a sound understanding of Kahn’s work is accessible to nearly anyone, though the emotional and profoundly moving qualities of the architecture are somewhat obscured by the exhibition’s extensive indexing of the forms.

![]()

-

Constructing Architecture

as Narrative SculptureA profile of Manuelle Gautrand Architecture

Text by Norman Kietzmann

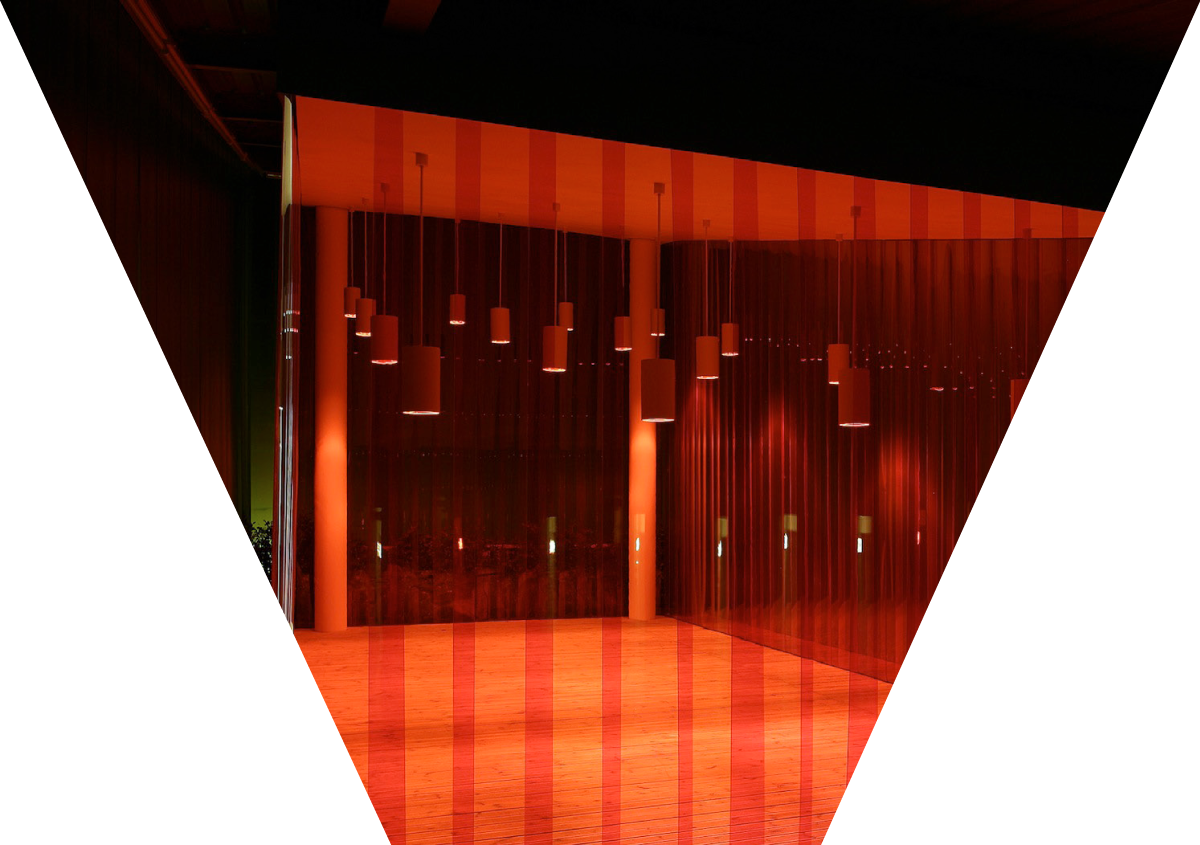

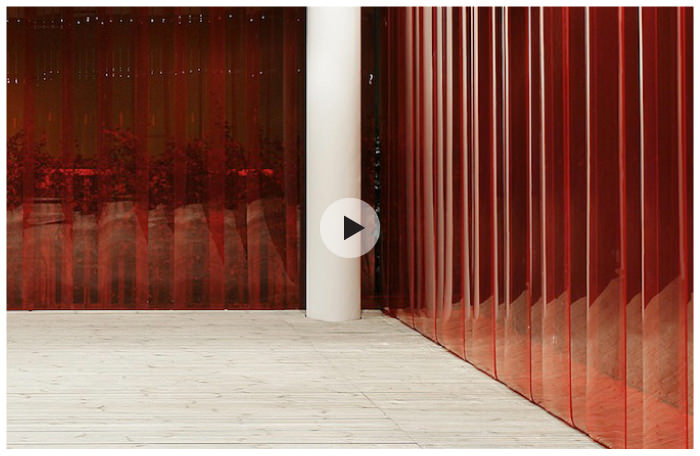

Gaite Lyrique, Paris, France. 2002-2010. (Photo © Philippe Ruault)

-

She has transformed auto showrooms into jewels, awoken an operetta theater from its slumber, and built impressive towers that engage with their surroundings. Manuelle Gautrand is not only France’s most exciting architecture export. The Paris-based architect and member of the Legion of Honor brings a sensual, sculptural quality to architecture from which not only her male colleagues could learn a thing or two.

A charming and motley collection of signs in the entrance drive to the Boulevard de la Bastille displays the firms that now occupy the onetime factory building, which dates from the turn of the century. There are many architects, graphic designers, press offices, two modeling agencies, and, at the very rear of the courtyard, the workshop of Hector Saxe. The highly-traditional factory still produces precious backgammon games by hand, and it is one of the last three of its kind. As Gautrand leads us around her office, she comments: “Many of our neighbors also work in the evening. That is good. It means you are never alone and you always see a light on somewhere else.”![]()

Origami Building, Paris, France. 2006-2011. (Photo © Vincent Fillon)

![]()

![]()

-

![]()

Origami Building, Paris, France. 2006-2011. (Photos © Vincent Fillon)

![]()

-

Seventeen architects work in her office on two bright floors, with light streaming through windows into the space, which measures some 280 square meters total. A further detail immediately strikes you, which is a clear departure from the furnishing of other architect’s offices: rather than the almost obligatory Tolomeo desk lamps, dozens of Japanese paper lanterns hang from the ceiling and lend the room a pleasantly warm air. “We are always easy to track down at night. Everyone in the courtyard calls us the ‘studio of the Chinese lanterns,” says Gautrand, laughing. There is something cheeky when she says things like this, and her infectious grin spreads from one ear to the other.

![]() Citroën Showroom, Paris, France. 2002-2007. (Photo © Philippe Ruault)

Citroën Showroom, Paris, France. 2002-2007. (Photo © Philippe Ruault)![]()

-

![]()

Citroën Showroom, Paris, France. 2002-2007. (Photo © Philippe Ruault)

-

Gaite Lyrique, Paris, France. 2002-2010. (Photo © Vincent Fillon)

-

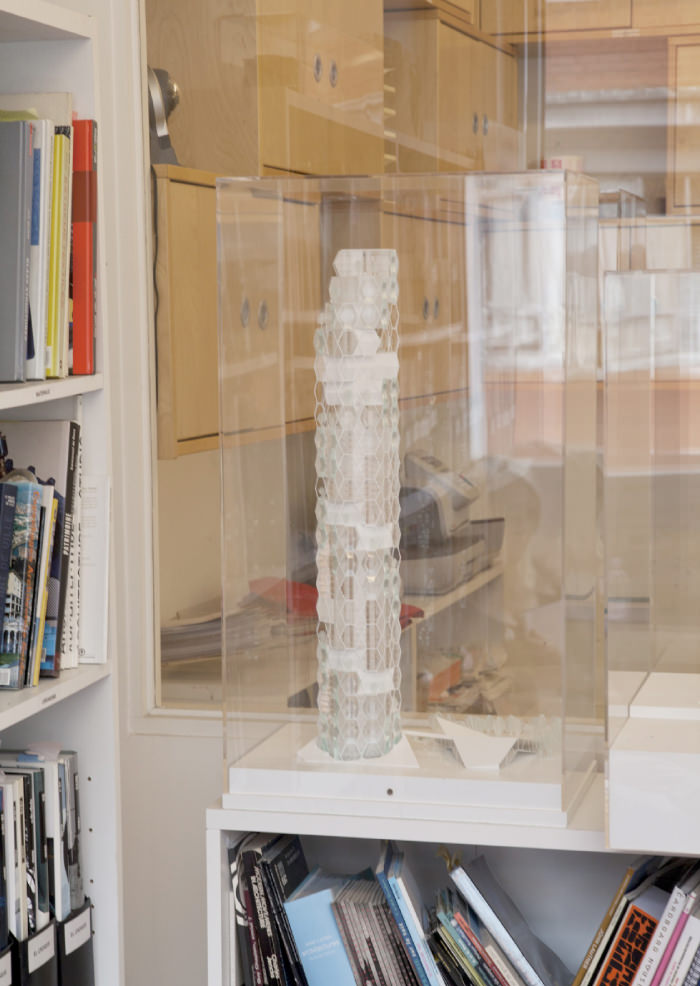

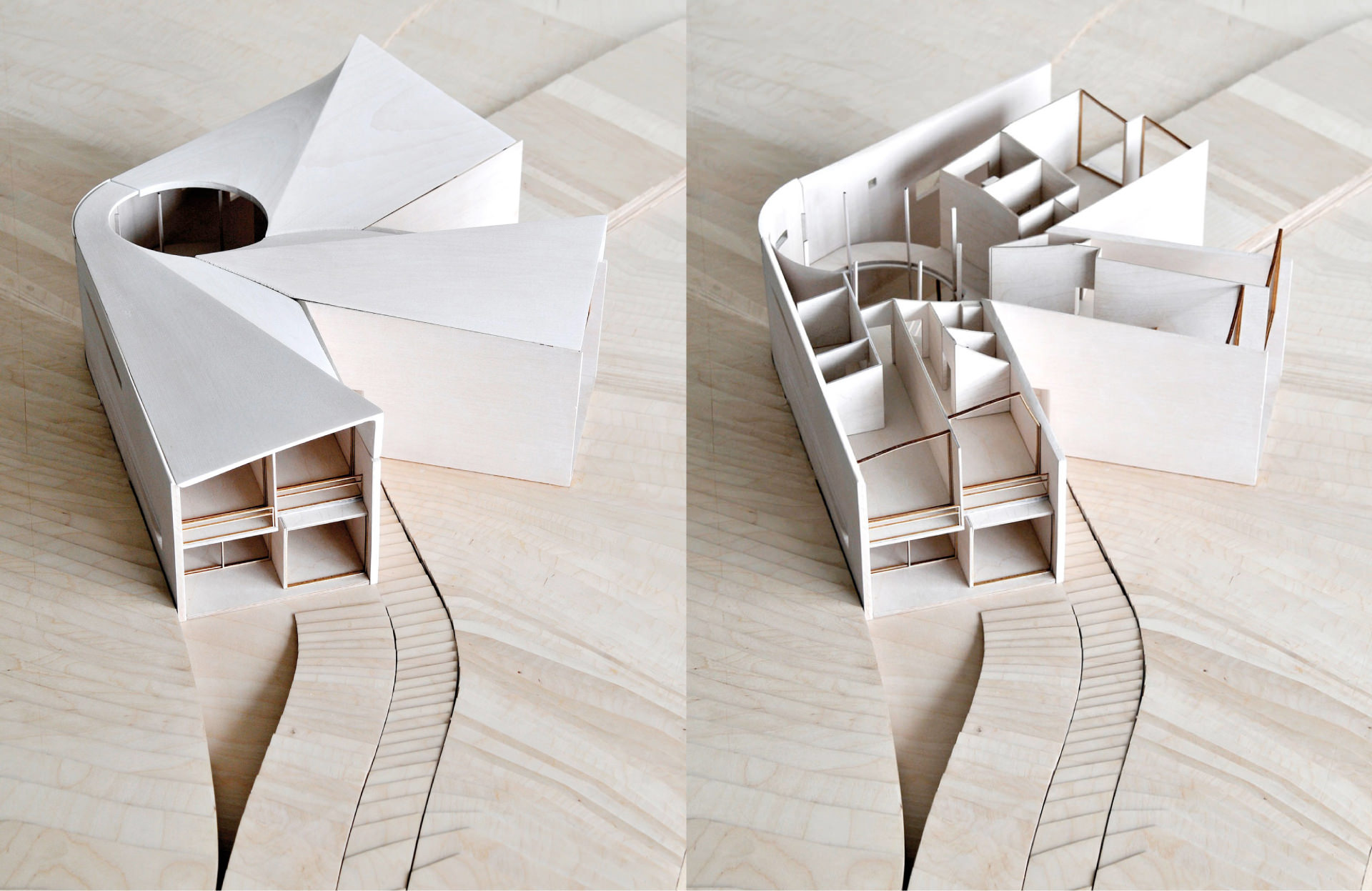

On the lower level right next to the entrance and conference room there is a large workshop. “We work intensively with models to experiment with as many different scenarios as possible,” the architect says, explaining the importance of this room. As we continue walking, employees keep disappearing into the glazed box of the workshop and return holding colorful foam objects. Her comments about working processes are also corroborated by a glance over the tables in the office, crammed full of models.

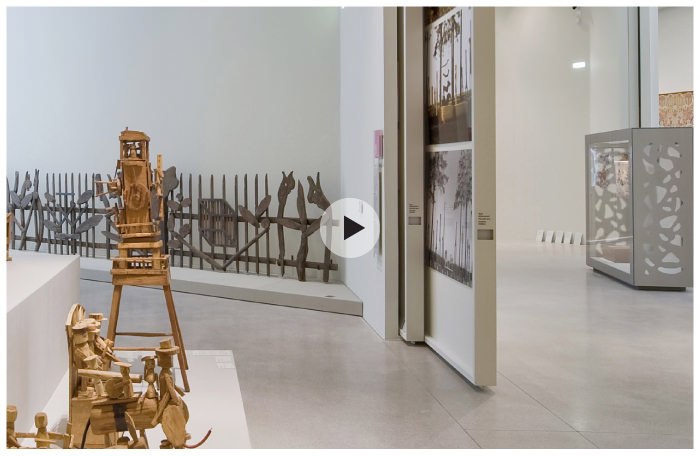

Gautrand can look back on an impressive career. Born in Paris in 1961, she has remained remarkably free of professional callousness or even arrogance. Yet there are several things that would merit her having a sizeable ego: her C42 Citroën showroom, which opened in 2007, is the first new building on the Champs-Elysées in 32 years and the only one designed by a woman. With the Gaîté Lyrique, which opened in 2010, she transformed a run-down 19th-century operetta theater into a vibrant center for contemporary music, which can claim nothing less than being the most important cultural building on the Seine for ten years.![]() Gaite Lyrique, Paris, France. 2002-2010. (Photo © Vincent Fillon)

Gaite Lyrique, Paris, France. 2002-2010. (Photo © Vincent Fillon) -

![]()

![]()

AVA Tower, Paris, France. In progress 2008 – 2015. (Photo © Platform)![]() Tena Resort, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. In progress 2011-2016. (Photo © Luxigon)

Tena Resort, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. In progress 2011-2016. (Photo © Luxigon)Phare Tower, Paris, France. Competition 2006.

(Photo © Platform) -

![]() AVA Tower, Paris, France. In progress 2008 – 2015. (Photo © Platform)

AVA Tower, Paris, France. In progress 2008 – 2015. (Photo © Platform)

Video: Design Animation by Manuelle Gautrand Architecture![]()

-

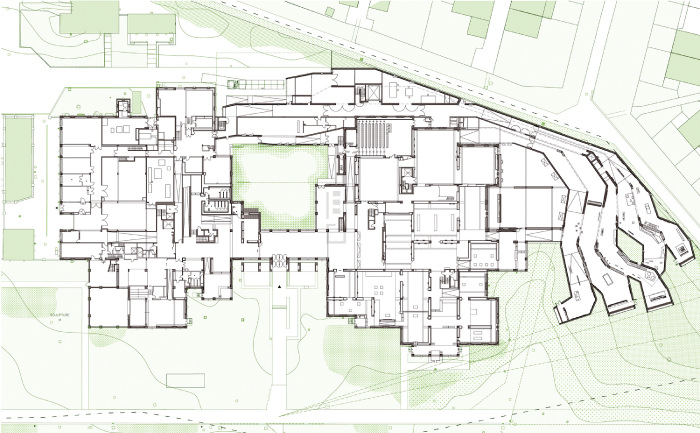

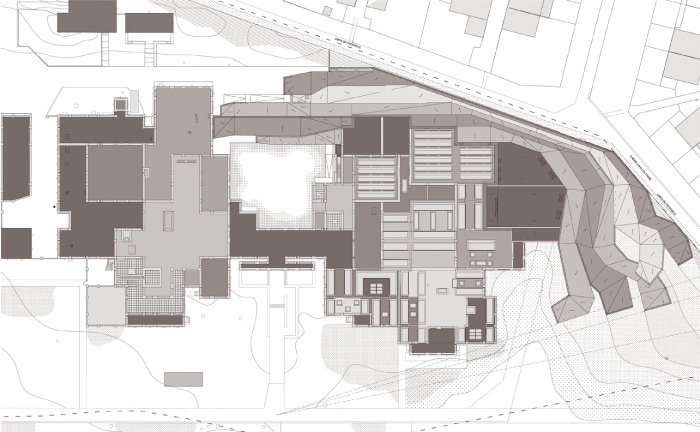

Modern Art Museum, Lille, France. 2002-2009. (Photo © Max Lerouge)

-

Modern Art Museum, Lille, France. 2002-2009. (Photo © Max Lerouge)

-

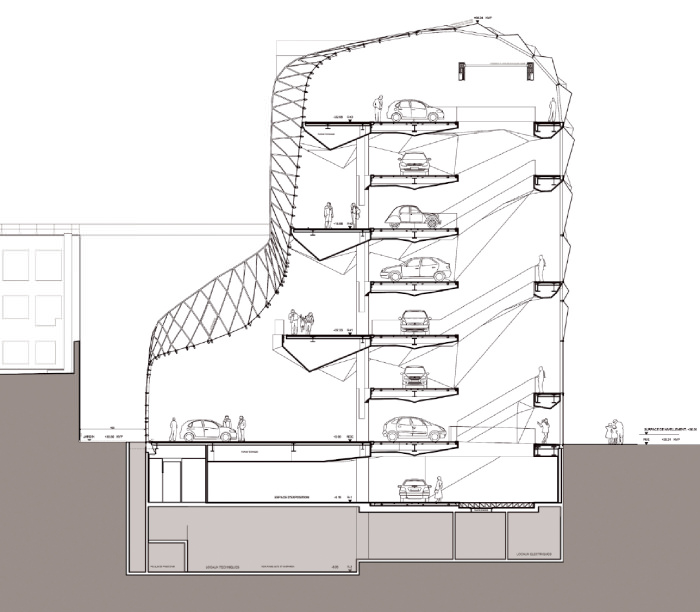

And while many high-rise projects in the La Défence financial district currently hang in the balance – or have been scrapped, like the Tour Signal designed by Jean Nouvel – her design for the 140-meter-tall Tour AVA will be completed in 2016. It is hardly surprising that this extremely busy Frenchwoman was made a member of the Legion of Honor in 2010.

Gautrand knows what she wants and what she does not want. She refuses point blank to reveal the names of the offices where she worked before setting up her own studio in January 1991. And we were only told the name of the university from which she graduated in 1985 – the Ecole Nationale Supérieure d‘Architecture de Montpellier – after asking several times. That sounds almost strange; she talks very openly about her projects and is not afraid to express her doubts. “I found studying a little frustrating,” she says; in those formative years she found her inspiration more in the sculpture studios than on the architecture floors. This affinity for sculptural design has remained with her, even though she now realizes it exclusively within the bounds of architecture.![]()

![]()

Modern Art Museum, Lille, France. 2002-2009. (Photo © Max Lerouge) -

Photo: Modern Art Museum, Lille, France. 2002-2009. (Photo: Max Lerouge)

Video: En Quête d’Oeuvre, presentation of the project by Pauline Thierry, 2008![]()

-

Cité des Affaires, Saint-Etienne, France. 2005-2010. (Photo © Vincent Fillon)

-

Yet buildings designed by Gautrand are by no means exaggerated sculptures, but rather buildings with sculptural qualities – as expressed in the Citroën showroom (2007) with its ingeniously folded façade, the extension building to the Museum of Modern Art in Lille (2010) with its leaf-like windows, or the Cité des Affaires office complex with bright yellow accents in Saint-Etienne (2010). At the Cité des Affaires the façade is charged with being much more than the climatic divide between the inside and outside. Using folds, curves, and a strong feeling of relief, the façade becomes a specific communication tool. It is Gautrand’s conviction that “every building in a city is an orientation point and should play a role.” She draws a comparison with figures on a chessboard.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Cité des Affaires, Saint-Etienne, France. 2005-2010. (Photo © Vincent Fillon) -

Munch Museum, Oslo, Norway. Competition 2009. (Photo © Luxigon)

-

![]()

Alesia & Mistral Cinemas, Paris, France. In progress 2011-2013. (Photo © Luxigon)

The kind of narrative qualities a building can embody is best demonstrated by Gautrand’s proposal for the new Munch Museum building in Oslo. “Edvard Munch is one of Norway’s national treasures as an artist. I liked the idea of creating a connection between the landscape and his painting. This is why the building draws heavily on nature and recalls the fjords, the mountains, and the dark colors of the sea,” says Gautrand while describing her design. She is still annoyed by the fact that her dark and meandering land- scape, which would have formed a striking contrast to the Opera House designed by Snøhetta, finally lost out to a neutral, almost run-of-the-mill design by Herreros Arquitectos from Madrid. A likeable reaction, as it reveals her passion for design. Her architecture does not evolve from working down spreadsheets or narrow planning grids, but from precise observation of the site and context. That makes it difficult for her to give up the solution she thinks is right.

-

![]()

Music and Dance Center, Ashkelon, Israel. In progress 2011-2014. (Photo © Manuelle Gautrand Architecture)

-

“Competitions are difficult because we lose a great many of them. On the other hand you do know when you win a competition that the design was right,” admits Gautrand. She saw it as a challenge when, in summer 2011, she received a direct commission for the new building of the Conservatory for Contem- porary Music and Dance in Ashkelon, Israel (construction is supposed to start in 2013). She remarks, “Naturally, the planning is ea- sier when you can realize a project precisely the way you want to and there are no rivals. But at the same time you are unsure whether the client will like the proposal and whether it is right,” explaining her ambivalence. Five days before the project presentation, little would indicate a frantic mood. Numerous models and renderings spill over two large desks at the center of the room and give a sense of the design. Incidentally, the doubts she articulated prove to be unfounded: with its interlocking volumes and the façade per- forated by round windows, the proposal met with approval – and construction will start next year.

![]()

Solaris Housing Block, Rennes, France. 2001-2006. (Photo © Philippe Ruault)

-

![]()

Solaris Housing Block, Rennes, France. 2001-2006. (Photo © Philippe Ruault)

Where else is the journey taking her? The projects that Gautrand is currently working on with her team include the expansion of a department store in Paris from the 1960s, the modernization and rejuvenation of two cinemas in Paris, a hotel/residential building in Montpellier, a luxurious residential complex in the Caribbean, a boutique of Louis Vuitton in Seoul, and the extension of a theater in Béthune, northern France. There is a special reason why, above all, the theater is close to her heart. “The theater was one of the first competitions I won in 1994. I am very, very happy to be able to design the new rehearsal rooms ten years after the opening,” confesses Gautrand as she smiles broadly again. The light in the studio from the Chinese lanterns is sure to burn bright for some time to come.

![]()

-

Folding Emotion

into Architecture

French architect Manuelle Gautrand on origami architecture, built emotions, and her wish to make a tower.

Interview by Norman Kietzmann

Photos by Torsten Seidel -

It is a warm September day in Paris. In the Port de l‘Arsenal, an inner harbor south of the Bastille, the boats belonging to leisure-time captains jostle for space. A line of trees separates the embankment promenade from the Boulevard de la Bastille, but the house at number 36 already strikes me from a distance. In place of the gray-beige sandstone or black cast-iron balustrades characteristic of downtown Paris, here a red-brick façade and finely structured concrete supports tell of an industrial past. People are constantly to-ing and fro-ing from the entrance to the former factory building. Taxis pull up and good-looking people carrying thick folders get out. I follow them into the building and upstairs, and find that a modeling agency on the third floor is running a casting for the upcoming Paris fashion week. A long corridor leads me ever deeper into the building. A door opens and in a bright, sun- glazed room surrounded by books, renderings, and models, I finally begin my interview with Manuelle Gautrand. We discuss urban games of chess, glass origami, and built emotion.

![]()

-

![]()

Madame Gautrand, when did you realize that you wanted to become an architect?

When I was seventeen. I knew that I wanted to take up an artistic profession but for a long time I was not sure which one. After my school graduation exams I decided it should be architecture. So I cannot claim that I was absolutely sure at the age of three (laughs).

What memories do you have of your studies?

They were a little frustrating because I did not believe that the school was all that good. In France the architecture schools are not that good in general. When I had finished my studies, I was really dissatisfied with what I had learned. It was only when I started to work that I gained professional experience and learned how to deal with my own creativity. My studies did not give me much in those respects.

-

But was there a professor who influenced you?

Yes, my sculpture professor. We primarily analyzed contemporary art, so I got to know it very well. However, in regard to the practical side of things, I can hardly remember the projects we worked on. What I enjoyed about sculpture was its open, fresh approach – something I found lacking in architecture and in my architecture professors. Even today, I think I tend to seek my inspiration outside of architecture, be it from landscapes, cities, or sometimes fashion.

The influence of sculptural design is especially evident in your façades, which are anything but strictly organized. You experienced a breakthrough career moment with the opening of the Citroën C42 showroom on the Champs-Élysées in Paris. Its façade is an undulating ribbon that merges seamlessly into the roof. How did you arrive at this design?

-

I must admit that I wasn’t much of a car fan to begin with. So I started by trying to immerse myself into the universe of automobiles and looking at how they are made and sold. Then it struck me that above all the DS, to date Citroën’s most beautiful model, resembles an endless curve. The showroom on the Champs-Élysées works the same way: it resembles the body of a car – the façade and the roof merge seamlessly.Yes, but that does not explain the folding...

The folding is very important because it tells of the building’s contents. The Citroën logo is a double inverted V that I find very attractive. In referencing this shape, the façade can embody the brand without having to feature the brand name, Citroën. The Japanese practice of origami allows one to express a feeling for an object through a fold. I tried to do the same with my building. It is an origami of glass.

![]()

»I tend to seek my inspiration outside of architecture, be it from landscapes, cities, or sometimes fashion.«

-

Large-sized glass façades can often appear cold or even banal. But the folding produces a differentiated play of light and shadow. What effect did you want to achieve with it?

A folded, glass facade recalls a kaleidoscope, which reflects the surrounding buildings or the sky. The reproduction is not a normal mirror, but instead divided into many different facets. This aspect was very important to me – I did not want the building to appear solid and lose something of its material quality. Each of the round platforms used to present the vehicles has a folded, reflective underside. When you climb up the stairs, the colors of the cars are reflected, while their shapes are almost completely obscured from below. This makes going through the building much more exciting because not everything is recognizable at first sight. The mirrors not only allow a new interpretation of the cars but also function a little like the disco globes in a nightclub, casting the diffuse light through the room.

-

»It is important for the architecture to sweat out a little of what is happening inside.«

So you wanted to communicate with the public space?

Yes, because most of my buildings are located in cities, which is why I would like to open them to the street, rather than making them asocial, autistic. Every building in a city is an orientation point and should play a role like a figure in a game of chess. Creating a connection between a building and its setting need not necessarily mean making its façade transparent; experimenting with volumes or colors can also make the function understandable. It is important for the architecture to sweat out a little of what is happening inside.

How do you approach a project?

I first think about the context and what is required of the building. That is normal. But at the same time I also try to think about the materials, the colors, and the atmosphere I want to create. What is the building’s relationship to light? Should the architecture let light into it or not? Should it be transparent or opaque? For me these aspects are just as deeply rooted in architecture as the function of a building or its connection to the site. It is important that a museum does not look like an office building.

-

![]()

Tell us about the work you do in your studio. How does the design process evolve?

We always work very intensively with models from the very start. In each and every project I try to play through as many different scenarios as possible. After all, each of these possible solutions contributes something to the final outcome. I spend a lot of time analyzing individual ideas before selecting the right one. However, there is still a very long way to go even after the first volume is built. I also try to be inventive with every project, either in relation to the function of the building, its context, or to the materials used. My work is not a linear process. In the beginning things often proceed very quickly, but then there is always a point at which things falter and we start to struggle for one, two, or three weeks. That is also normal. In such moments it is important to talk a lot with each other so as to find a logical explanation for a proposal. Language is an important design tool.

-

You have a broad spectrum of work: you design cultural buildings like theaters and museums, and you also plan office buildings, residential buildings, and bridges. One typology to which you have applied yourself more in recent years is the high-rise. What pushes you up to such dizzying heights?

Naturally, for every architect building a tower is a heroic act just waiting to be accomplished. And I am no exception. But my interest also arose from a certain criticism. After all, although there are ever more towers in the world, only a handful of them are really interesting. Most high-rises tower up into the sky really brashly and brutally without being connected to the ground. Yet the first thing that you see of a high-rise when you are near is its base. I think that at this point it needs a human, almost intimate scale. Conversely, from a distance it is the tip that is especially eye-catching and less the body of the tower. So it is important not to ignore these zones. A high-rise always forms three sequences of understanding.

Although you did not win the competitions for the Tour Phare (2006) or the Tour Signal (2008), in 2008 you were able to secure a large-scale project in Paris’s new high-rise district, La Défense. This was the construction of the 140-meter-high Tour AVA. Why were you able to beat out your rivals with your design?

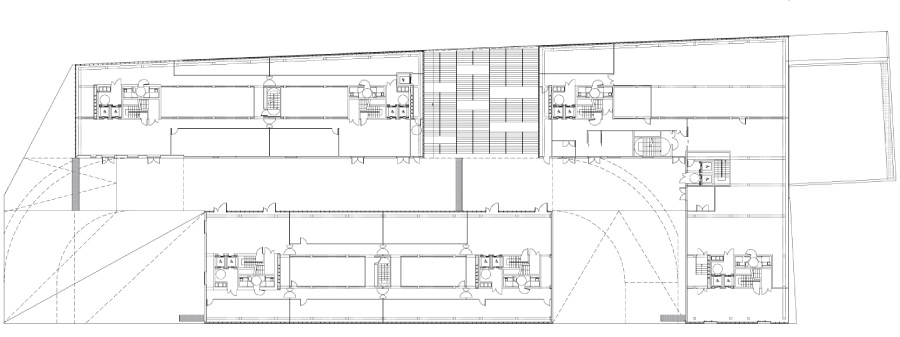

The project was not easy at the beginning because the site is bisected by a motorway. Initially, we only had the site at the northwest side of the street to work with. So I suggested making the building larger and pushing it below the viaduct. The developer was very taken with this proposal because it meant shifting the building’s entrance to the center of La Défense and the motorway loses its visual presence. The tower will rise up 140 meters vertically with a 200-meter-long base, so the building is actually more horizontal in thrust.

You also employed the motif of folding in your design of the base section. -

»Naturally, for every architect building a tower is a heroic act just waiting to be accomplished. And I am no exception.«

-

![]()

Yes, the entrance is placed underneath the motorway like a large awning and creates a small entrance piazza. It provides protection from the rain and features a screen of LEDs underneath. This roof, which will be lit day and night, will be a projection screen for short films or digital art. I often work on cultural projects such as theaters or concert halls. My affinity with this cosmos also provides me with ideas for other projects, which do not initially have a direct link to culture. I am not trying to make architecture theatrical but I would like people to experience something in it.

In other words, architecture becomes a medium?

Absolutely. I do not want my buildings to be neutral, even if they are simply places where people work. Architecture should evoke emotion. Whether we live, work, or watch a play in a building, it can offer us an experience. It is important that the architecture is infused with a conscious scenography.

-

![]()

Your most important project to date was the conversion of the Gaîté Lyrique in Paris. You transformed the operetta theater from the 1870s into a center for contemporary music that opened in December 2010. Despite your pleas for an emotional architecture there is an almost neutral feel to the rooms for concerts, film presentations and performances. Why?

It is important to create a strong, independent architecture without going too far. In some places the Gaîté Lyrique is highly expressive – say, in the mobile elements, which double as lighting. The technology is very sophisticated so that you can do anything you like in these rooms. But at the same time, thanks to the gray floor, white walls, and black performance spaces, the building itself remains in the background. With cultural projects it is important to hand on the baton to other artists. You must give them the opportunity to express themselves in the spaces, so they aren’t overly restricted by too expressive an architectural gesture.

Thank you very much for the interview.

![]()

»I do not want my buildings to be neutral, even if they are simply places where people work.«

-

![]()

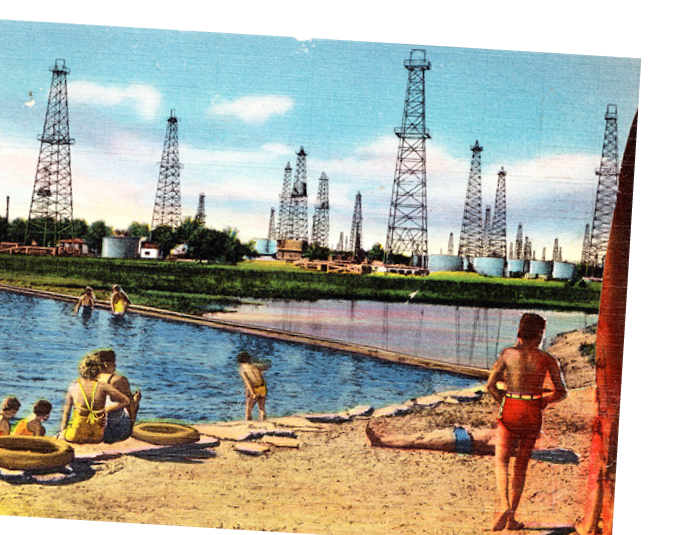

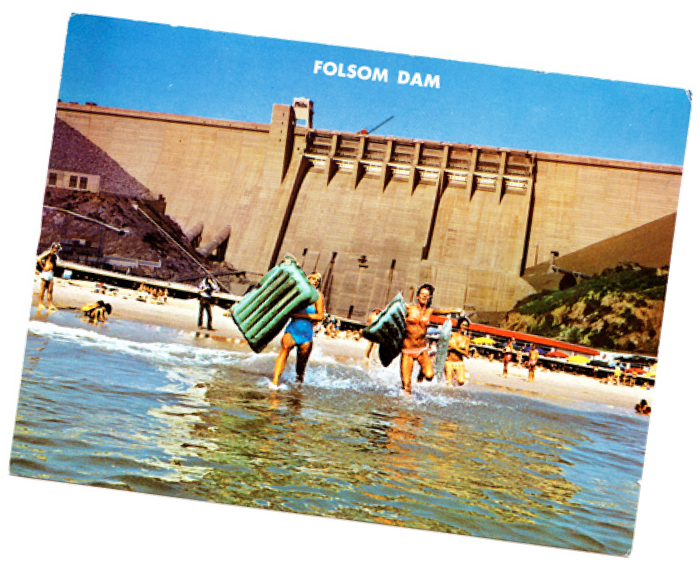

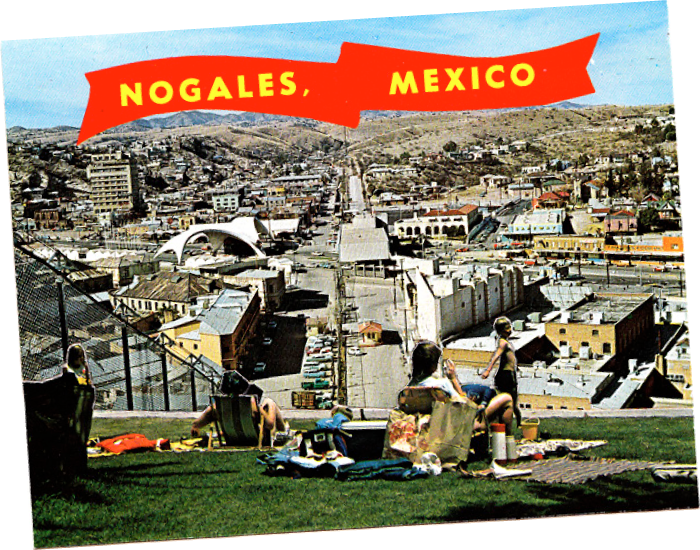

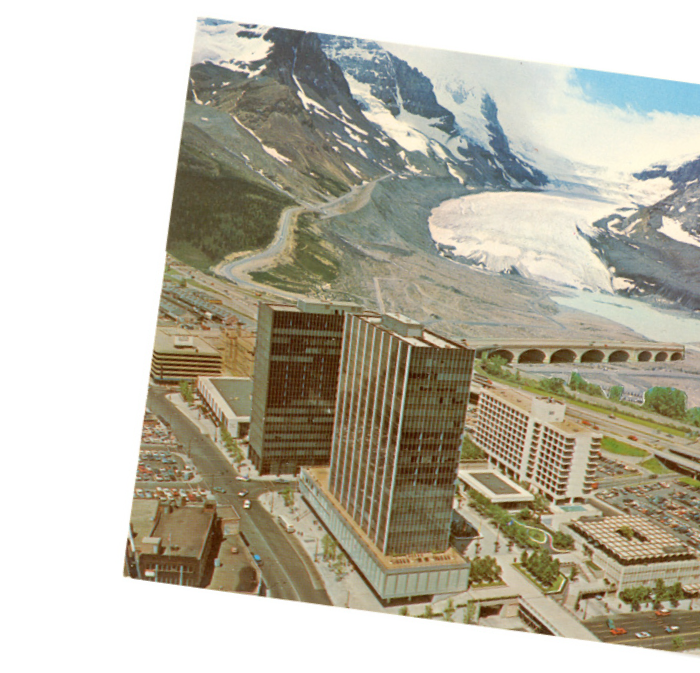

Hypertopia Remix

American artist Mary Lydecker’s hypertopic images are remixed tourist postcards from the 20th century, painstakingly collaged by the artist for perspectival perfection. Often pairing the mundane with sublime sights or infrastructure, the cards portray an American past which is at once dystopian and desolate as well as utopian with a certain yearning colored by the warm tones of a nostalgia for what never was.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

-

Bostjan Vuga is currently guest professor at Adip, TU in Berlin. He attended the Faculty of Architecture in Ljubljana and the AA School of Architecture in London. He has lectured, taught, and been a critic at architectural schools, conferences, and symposiums in Slovenia and abroad, including the Berlage Institute in Rotterdam, the AA School of Architecture, the Bauhaus Kolleg in Dessau, the IAAC in Barcelona, at the ETH in Zuerich, and at the Universitaet fuer Angewandte Kunst Wien and Academy of Visual Arts Vienna. As a visiting editor, he took part in two issues of AB Architectural Bulletin. He has published numerous articles about architecture and urban planning, and presented in national and international, professional- and general-interest publications. www.sadarvuga.com

![]()

In the Photo Booth with...

Bostjan Vuga

We invited Bostjan Vuga, principal of Slovenian architecture office SADAR + VUGA, to step into our photo booth. With the recent publication of Sadar + Vuga: A Review, the office is growing in recognition internationally and expanding its project base globally. Bostjan answered our questions with his signature – and amusing – grace and aplomb.

Interview by Jessica Bridger

-

What brings you to Berlin?

I am a guest professor in the Architecture Design Innovation Program at the TU Berlin. But also my best friend lives in Berlin, so I was often in Berlin even before my guest professorship. -

What is your favorite urban space in Berlin?

Ku’damm, as the only real street space for flaneurs, for promenading in Berlin. With its distinctive patina and charm of 1970s glam. Also the space around the Bikini-Haus, near Berlin Zoo station. I am sure this area will be back in full effect as soon as the in-progress renovation of the building is completed. -

What is your favorite project that you’re currently working on in your office?

A small boutique hotel in the old town of Ljubljana. It is composed of four medieval houses converted into a special kind of urban resort. The design is trans-atmospheric: where M.C. Escher patterning meets Venice. -

Do you think your architecture is still rooted in Slovenia even though SADAR + VUGA practices widely internationally? How so?

We are based in Slovenia and 80 percent of our projects are still designed for sites in Slovenia – and percent of those in Slovenia are in Ljubljana, where our office is situated. Ten buildings that we designed have been completed in Ljubljana since 1999. Since we live and work here, we can observe how the buildings age: how they change with usage on one hand, and influence change in the city on the other, for example, triggering similar construction, becoming a new destination, and influencing social behavior. People go to our National Gallery of Slovenia building even without the intention to visit an exhibition – a sports park has become a new playground and informal event space… -

What’s the best-designed fruit?

Passion fruit. The name says it all. And you are triggered (and tempted) to explore it as a good “architectural” design.![]()

If you could do any project what would it be?

Uff. A winter collection of environment and mood responsive outfits. For men and women. -

![]()

N E W

ARCADIANS

Economic Gloom sees young

UK architects get creative

with their practicesText by Lucy Bullivant

-

In the UK today, with government initiatives cut back and relatively few competitions, young architects have fewer options than they did five years ago before the crisis began to bite. However the most progressive architecture is often produced in periods of economic and political crisis. During times of austerity and emergency, otherwise apparently autonomous tectonics invariably take on other identities, and the art of relational urbanism and improvised organisation comes to the fore. Entropy precedes a new kind of breeding space.

An architecture not limited to buildings

Through reduced budgets, improvised means and digital-analogue projects, the pop-up, the agitprop, the near-spontaneous happening, community games, and above all, political involvement, a counter-practice of experimentation enables a more responsive mode of practice and interactive cultural projects in an age of austerity -- without the time scale or investment conventionally required in the boom times. Just as optimists like to believe, crisis can also be opportunity. Architectural concepts from the young and emerging offices in the UK have become temporary, reconfigurable, or allied to public art. As the late, radical English architect Cedric Price anticipated in the 1960s, sometimes the best solution is not a building. In my new book, New Arcadians: Emerging UK Architects, I analyse the social engagement of 18 young practices and their commitment to affordable, robust solutions.

Alternative approaches to architecture during the current malaise in the UK may have been temporarily overshadowed by the glory and buzz of the London Olympics, and the culmination of its six-year building programme, but as Stuart Piercy of Piercy Conner Architects, one of the practices featured, says: -

![]()

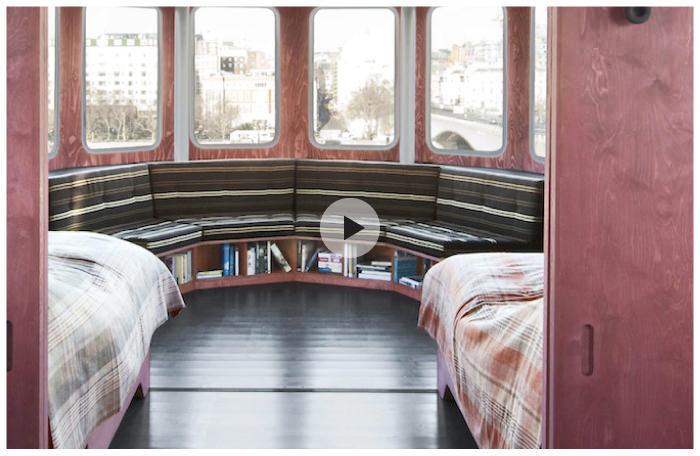

A Room for London, David Kohn. (Photo: David Kohn)

Video: As part of an event series in A Room for London, British artist Jeremy Deller invited musician Chuck to join him and perform a few songs together high above the Thames. (www.aroomforlondon.co.uk) -

![]()

![]()

![]()

David Kohn working with artist Fiona Banner, designed A Room for London (2012), a rentable boat-type structure that sits on the roof of the Queen Elizabeth Hall on the South Bank in London, and is designed for two people to stay in overnight. (Photos: David Kohn)

-

“We are part of a generation that had witnessed only economic prosperity, and when things turned ugly in the UK, suddenly the whole process of renewal just stopped…At times like this there is a lot of reflection on the value of architecture, and I am afraid the government has made it very clear that it sees design as a luxury. Thankfully, not all clients are as shortsighted, and we have experienced a renewed interest in young practices as people who can offer a fresh look at old problems”.

In spite of the difficulties, the inspirational concepts of younger practices have drawn clients excited by the possibilities of innovative speculation. Bending planning regulations or changing the playing field in the first place through participatory methods is becoming increasingly common, with architectural practices such as AOC skilled in creating clearly structured narrative journeys through processes and devising interactive urban design games such as Building Futures and Polypoly; another practice, Mae, created Prospectopolis, a community game to aid consultation for the North Prospect area of Plymouth.

Shifting Practices

Three practices that have successfully negotiated the UK’s new conditions are David Kohn Architects, OSA (Office for Subversive Architecture), and Serie – all of whom have coincidentally worked on projects in or around the periphery of the Olympic site.

David Kohn pledges “to work with others to bring about enduring and beautiful backgrounds for social interaction”. Rather than simply canvassing local opinion for his latest arts centre scheme in east London, which overlooks the Olympic Stadium, he is undertaking the project in collaboration with local businesses. Here, contributing to the future infrastructure the site needs around its periphery, Kohn has just finished transforming an old print works – once used for illegal parties – into The White Building, a local arts centre. The practice won this project in a competition and realised it in collaboration with Michael Pawlyn of Exploration Architecture, specialists in environmentally sustainable design. -

![]()

![]()

David Kohn’s Skyroom is a roof-top pavilion, with a simple ETFE roof, designed for the Architecture Foundation in Bermondsey, London (2010) to hold events. (Photos: Will Pryce)

-

David Kohn opts for a heterotopian vision similar to that defined by Foucault in his essay, Of Other Spaces (1967), which has helped him understand real spaces that operate as utopias. The work of his practice possesses a myriad of narrative references, including A Room for London, the Flash pop-up restaurant at the Royal Academy of Arts, and the Skyroom. In his recent essay Jujitsu Urbanism (2010), Kohn differentiates between hard and soft techniques, the latter harnessing and redirecting the energy of an opponent to both disarm and win the adversary over, which requires flexibility and skill.

![]() The White Building is a new arts centre converted from an old print works in London’s Hackney Wick, commissioned by the London Legacy Development Corporation and designed by David Kohn (Photos: David Kohn)

The White Building is a new arts centre converted from an old print works in London’s Hackney Wick, commissioned by the London Legacy Development Corporation and designed by David Kohn (Photos: David Kohn)![]()

-

Office for Subversive Architecture (OSA) was born in 1995, when a group of German architecture students joined forces on a project. Instead of creating a company, they formed a network and collective of like minds in the fields of architecture and public space. Now there are eight partners based in seven cities: Vienna, Frankfurt, Darmstadt, Dortmund, Graz, Hamburg, and London -- where the OSA office is run by Karsten Huneck and Bernd Trümpler. They are no strangers to the Olympic site: Point of View (2008) was installed without planning permission against the perimeter fence, drawing attention to the distancing of the wider community. Four years before, OSA illegally mad-over a disused railway signal box in Shoreditch as a miniature cottage, complete with (plastic) geraniums in the windows, a project that was later rendered uninhabitable by the authorities.

![]()

![]()

OSA’s Point of View (2008), the first viewing platform for the Olympic site, was constructed and set against the perimeter fence of its construction site. Installed without planning permission, it lasted only 60 hours before being removed – but by drawing attention to the security fence that blocked the view of the site, it also effectively underlined the wider separation of the local community from the project. (Photos: OSA)

-

OSA’s Accumulator project (2008), at a public swimming bath in Leeds dating from the 1960s, featured a gigantic funnel – a “virtual water collector” – symbolizing architecture’s yearning to be sustainable, a fitting adieu to a building that was scheduled for demolition due to energy inefficiency. (Photo: Phillip Day)

-

![]() In 2004, OSA illegally made-over a redundant railway signal box in Shoreditch, transforming it into a little half-timbered cottage. Named Intact, this project was later rendered uninhabitable by the authorities. (Photo © Trenton Oldfield)

In 2004, OSA illegally made-over a redundant railway signal box in Shoreditch, transforming it into a little half-timbered cottage. Named Intact, this project was later rendered uninhabitable by the authorities. (Photo © Trenton Oldfield)![]() OSA’s roof pavilion for the Blade Factory in Liverpool enabled new views over the River Mersey and the city centre, forming a place for discussions that was jokingly named Kunsthülle, or “Art Wrapper.” (Photos: Johannes Marburg)

OSA’s roof pavilion for the Blade Factory in Liverpool enabled new views over the River Mersey and the city centre, forming a place for discussions that was jokingly named Kunsthülle, or “Art Wrapper.” (Photos: Johannes Marburg)![]()

![]()

OSA see themselves as a research lab for creative possibilities between art and architecture. This has been a niche market for some time, and many younger practices rely heavily on commissions for small, temporary installations. OSA, as artist-architects, can be meaningfully transgressive, realising new perceptions of existing and new spaces, form and social activity, as a vital new layer of information.

-

![]()

Photo: OSA’s roof pavilion for the Blade Factory in Liverpool. (Photo: Johannes Marburg)

Video: A short film by Sara Muzio with her impressions of Kunsthuelle Liverpool (2007). -

Serie Architects was founded in 2006 by Chris Lee and Kapil Gupta, graduates of the Architectural Association in London and Mumbai (now run by Gupta), with a third office opening in Beijing a year later. Riding on a mix of advanced skills and a very particular cultural approach, the practice has grown from three to thirty people in only two years, winning seven first prizes in four and a half years. “The challenge I see now is to realise our larger projects the way we want them to be, as the construction industry in China and India is very different to that in the UK,” says Serie. Serie’s work is geared towards exploiting the creative potential offered by dominant types and typical elements and ideas of the city. “We hope our architecture will turn out to be one that is generous to the city and that speaks the common language of the context in which it sits, making it truly public”, says Lee.

![]() Housing developments today need to balance the efficient use of land and resources, whilst maintaining a sense of privacy for residents. Serie Architects’ Bohacky Residential Masterplan in Bratislava, Slovakia achieves these goals with a typology of courtyard houses in wooded clearings. (Photo: Serie Architects)

Housing developments today need to balance the efficient use of land and resources, whilst maintaining a sense of privacy for residents. Serie Architects’ Bohacky Residential Masterplan in Bratislava, Slovakia achieves these goals with a typology of courtyard houses in wooded clearings. (Photo: Serie Architects) -

![]()

Bohacky Residential Masterplan (Photo: Serie Architects) -

![]()

![]()

Among Serie’s many conversion and renovation projects, this former factory in Hangzou, China was designed to create a new urban hub, whilst respecting the historical context of the factory. (Design animation: Serie Architects)

Winning the contest for The New Singapore Subordinate Court Complex has raised Serie Architects’ international profile. This project for a sustainable tower -- with passive energy strategies, high-rise gardens and naturally ventilated corridors - uses a design language intended to be readily understood by all Singaporeans, demonstrating how the practice’s work references the local cultural context. (Photo: Serie Architects)

-

The practice’s body of work, including a residential masterplan for Bratislava conceived as a forest with clearings, new buildings such as schools, and conversions of disused buildings, has recently been joined by the BMW Pavilion, designed for the London Olympics, which sat on a plinth with a cascading waterfall. Now after the Games, it is one of nine different pavilions, clustered as a family, that are being removed and transported to different locations. But it is a recent competition win for The New Singapore Subordinate Court Complex that has propelled Serie into the big time,one that demonstrates the particular ways in which Serie always immerses itself in the cultural and intellectual context of a place.

Creating Futures

When design is not on the menu of central government, society’s basic needs have to be attended to and their fulfillment rises to the top of the agenda. In a mature design culture such as the UK’s, the ingeniousness of practitioners has to go somewhere.![]()

BMW Pavilion designed by Serie Architects. (Photos: Edmund Sumner)![]()

-

Serie’s ingenious conversion of disused buildings within the Mumbai Race Course resulted in a group of restaurants and bars, including this banquet hall. Following specific conservation guidelines, the architects incorporated tree branch-type forms into the building’s design, creating a striking continuity with its tree-filled surroundings. (Photo: Fram Petit)

-

Lucy Bullivant Hon. FRIBA is an architectural curator, writer, critic, and lecturer. Born in London, she has a Master’s degree in Cultural History from the Royal College of Art in London. As well as New Arcadians, she is the author of Anglo files: UK Architecture’s Rising Generation (2005) and Responsive Environment: Architecture, Art and Design (2006), amongst other books. She is a correspondent for publications including Domus and Architectural Review, and curates and chairs the Talking Architecture series at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

New Arcadians: Emerging UK Architects

Lucy Bullivant

256 Pages, Hardcover

Merrell, 2012

Link: New Arcadians

![]() (Photo: Fram Petit)

(Photo: Fram Petit)The period of reflection and improvised experimentation ushered in by economic crisis has led to the crystallisation of opinions perhaps less vocalised in the past and incisive strategies for social change. I asked all the practices featured in New Arcadians to cite one single improvement they would recommend for the procurement of architecture in the UK. Holger Kehne of Plasma Studio and Groundlab (co-founded with Eva Castro) answered, “I think it is all in dire need of improvement. A single improvement would be at odds with the others, so any real progress would have to be based on a gradual shift of all factors and processes, with the underlying cultural acceptance that environmental quality is an asset, not just a luxury”. The relationship between needs and assets, articulated by younger practices through narratives and alternative technical procedures, brings a fresh calibration and opening up of future possibilities.

The best way to predict the future is to create it, but this is often in a form that lies beyond the norm of individual buildings, as Price suggests.![]()

-

NEXT

CONCRETE

In our next issue we’ll deal with every architect’s favorite material: concrete! We’ll be unearthing some solid ideas from the past and the present, including a look at 109 Architects' brand-new St. Joseph University campus in Beirut and a visit to Spain’s concrete vacation village of Benidorm. Furthermore, we’ll introduce you to the future of concrete: BLINGcrete!

![]()

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Less is a bore.«

Robert Venturi

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents

Citroën Showroom, Paris, France. 2002-2007. (Photo © Philippe Ruault)

Citroën Showroom, Paris, France. 2002-2007. (Photo © Philippe Ruault)

Gaite Lyrique, Paris, France. 2002-2010. (Photo © Vincent Fillon)

Gaite Lyrique, Paris, France. 2002-2010. (Photo © Vincent Fillon)

Tena Resort, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. In progress 2011-2016. (Photo © Luxigon)

Tena Resort, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. In progress 2011-2016. (Photo © Luxigon) AVA Tower, Paris, France. In progress 2008 – 2015. (Photo © Platform)

AVA Tower, Paris, France. In progress 2008 – 2015. (Photo © Platform)

In 2004, OSA illegally made-over a redundant railway signal box in Shoreditch, transforming it into a little half-timbered cottage. Named Intact, this project was later rendered uninhabitable by the authorities. (Photo © Trenton Oldfield)

In 2004, OSA illegally made-over a redundant railway signal box in Shoreditch, transforming it into a little half-timbered cottage. Named Intact, this project was later rendered uninhabitable by the authorities. (Photo © Trenton Oldfield) OSA’s roof pavilion for the Blade Factory in Liverpool enabled new views over the River Mersey and the city centre, forming a place for discussions that was jokingly named Kunsthülle, or “Art Wrapper.” (Photos: Johannes Marburg)

OSA’s roof pavilion for the Blade Factory in Liverpool enabled new views over the River Mersey and the city centre, forming a place for discussions that was jokingly named Kunsthülle, or “Art Wrapper.” (Photos: Johannes Marburg)

Housing developments today need to balance the efficient use of land and resources, whilst maintaining a sense of privacy for residents. Serie Architects’ Bohacky Residential Masterplan in Bratislava, Slovakia achieves these goals with a typology of courtyard houses in wooded clearings. (Photo: Serie Architects)

Housing developments today need to balance the efficient use of land and resources, whilst maintaining a sense of privacy for residents. Serie Architects’ Bohacky Residential Masterplan in Bratislava, Slovakia achieves these goals with a typology of courtyard houses in wooded clearings. (Photo: Serie Architects)

(Photo: Fram Petit)

(Photo: Fram Petit)