-

Magazine No. 04

Concrete

-

No. 04 - Concrete

-

page 02

Concrete

-

page 03

Editorial

-

page 04 - 15

Costa Concrete

The high-rise vacation city of Benidorm

-

page 16

Grand Massif

-

page 17

Trash Cube

-

page 18 - 23

In the Photo Booth with...

Heike Klussmann and Thorsten Klooster

-

page 24

Just Add Water

-

page 25

Concrete Coffee Lovers

-

page 26 - 41

Beirut’s Saint Joseph University

Youssef Tohme and 109 architects use concrete to raise questions

-

page 42

Double Spiral

-

page 43 - 48

A Brutalist Love Story

Boston City Hall

-

page 49

Heal Thyself!

-

page 50 - 51

Bookmarked

-

page 52

Next Issue

-

-

uncube’s editors are Elvia Wilk, Florian Heilmeyer, Jessica Bridger, and Rob Wilson. uncube is based in Berlin and is published by BauNetz, Germany’s most-read online magazine covering architecture in a thoughtful way since 1996.

We love concrete. You love concrete. We know it. It is the muse of modernism, the wet, heavy friend of sidewalks, buildings, and even — as you’ll see — a coffee machine.

This issue of uncube is our emphatic embrace of a single material, one that is so versatile that we can use it to take you from sustainable beach tourism in Spain to a massive structure in cold Boston - there are perhaps 5,000 applications of our greyish, rough-and-ready friend concrete, and we did our best to feature some of our favorites.

Plus! Introducing a new feature: Bookmarked, where the uncube editorial team picks some highlights from the world of publications.Cover Photo: Miguel Loos

-

Costa Concrete

The high-rise vacation city of Benidorm

Text by Anneke Bokern

Photo: Alejo Bagué

-

Benidorm is considered by many to be the biggest eyesore on the Costa Blanca. With its interchangeable architecture and uninterrupted concrete, the compact tourist hotspot is not exactly beautiful. On the other hand, its high-rises are extremely spatially efficient compared to the usual holiday resorts. This stronghold of bargain travel, of all places, has become a model for sustainable beach tourism.

The Costa Blanca is not beautiful. An endless sprawl of housing developments and holiday resorts lines the coast, interrupted here and there by a dusty business park and, of course, by the Benidorm skyline. Granted, the tourist town is not exactly known for its beauty, either — still, its sleek skyscrapers, rising like French fries from the monotony of the urbanizaciones, certainly make an impression. What’s more, few places are as polarizing as Benidorm: Giant low-cost developments and the MVRDV study Costa Iberica, budget tourism and sustainability. How do these things fit together?

Coming by highway, one approaches Benidorm’s absurd skyline gradually — and suddenly finds oneself right in the middle of it. Benidorm has no periphery in the classical sense of the word. The high-rises shoot abruptly out of the arid earth. At the very first roundabout stands the 40-story Neguri Gane, Spain’s tallest residential tower. It’s hard to believe that just 50 years ago, a fishing village stood at this spot. These days, Benidorm is home to 373 high-rises with more than 12 stories, making it the world leader in per capita density of skyscrapers — a title mainly attributable to the fact that Benidorm has only 70,000 permanent inhabitants. In the summer, however, the number of residents swells to 500,000. A full 11 percent of Spain’s tourism revenue is generated in Benidorm alone.![]() This and following photos: Miguel Loos

This and following photos: Miguel Loos -

![]()

»These days, Benidorm is home to 373 high-rises with more than 12 stories, making it the world leader in per capita density of skyscrapers.«

The world’s highest density of high-rises

Benidorm’s development started in the 1950s, when it was still a little village perched on the dead rock between two peaks, home to 2,700 inhabitants. Back then, Mayor Pedro Zaragoza realized the potential of the seven kilometers of sandy beaches and, in 1953, formed an initial development plan. The modern tourist town was meant to be green and airy; as such, only 30 percent of every plot could be developed. And so the first hotels went up, surrounded by gardens, and it wasn’t long before the first visitors followed. This burgeoning boom was almost nipped in the bud when, in 1959, an Englishwoman was fined for wearing a two-piece bathing suit — a bikini — to the beach, which was prohibited in Spain. To avert a possible tourism catastrophe Mayor Zaragoza locally abolished the bikini ban, whereupon the Bishop of Orihuela threatened him with ex-communication.

-

»The high building density is also a reason that Benidorm — as unlikely as it sounds — has long been viewed as a model for sustainable tourism.«

-

»This burgeoning boom was almost nipped in the bud when, in 1959, an Englishwoman was fined for wearing a two-piece bathing suit — a bikini — to the beach, which was prohibited in Spain.«

![]()

![]()

-

Undeterred and determined, Mayor Zaragoza then jumped on his scooter, drove six hours to Madrid, and obtained a meeting with Spain’s iron-fisted ruler General Franco, who promptly granted an exemption to his trusty follower. Four years later, with Benidorm flourishing more than ever, the building height restrictions were lifted to accommodate the influx of sun-seekers. In 1963, the first high-rise went up: Torre Benidorm.

Strangely enough, Benidorm doesn’t really feel like a big city — skyscrapers notwithstanding. Everything is remarkably clean and orderly; the flowerbeds are maintained, the traffic flows regularly. Retired couples in Bermuda shorts amble along the sidewalks. It’s low season. At a pool tucked between several hotel towers, only a single group of bare-bellied English tourists bellow a drinking song that echoes between the walls. And there are plenty of walls in Benidorm: the backs of the high-rises are completely windowless. In this mono-functional city, everything is oriented towards the beach. Almost all the buildings, even those many blocks back, face the sea, turning a concrete wall to the hinterlands, sometimes adorned by a lone fire escape. Along with the highest per capita density of high-rises, Benidorm must surely also boast the world’s highest per capita density of concrete backsides.

Is this the face of sustainability?

But the high building density is also a reason that Benidorm — as unlikely as it sounds — has long been viewed as a model for sustainable tourism. As Markus Lanz and Sophie Wolfrum wrote in the catalogue to the 2007 exhibition Multiple City, more was built on the coast of Valencia in the last decade than during the entire history of development there. While the coastal region gradually disappears beneath![]()

-

![]()

![]()

-

Photo: Miguel Loos

-

a ragged carpet of sprawling vacation resorts, Benidorm accommodates four million visitors annually on just 38 square kilometers. And it’s not only the economical use of space that’s exemplary, but also the water consumption: the average Benidorm tourist uses (directly and indirectly) 140 liters of water per day, which, according to sociologist José-Miguel Iribas, is just a quarter of what tourists in typical vacation homes use. An astonishing 97 percent of this water gets recycled as grey water. On top of that, low-energy lamps light the streets of Benidorm, and Benidorm visitors travel primarily on foot. The average tourist walks 14 kilometers per day through the streets and along the beach promenade — a car, after all, is not usually included in holiday packages. The importance of this promenade, designed in 2009 by Barcelona’s Office of Architecture (OAB), is immediately apparent: organically meandering and paved with colorful ceramic tiles, it looks like a cross between Burle Marx’s legendary Copacabana promenade and Gaudí’s Park Güell in Barcelona.

This idiosyncratic combination of budget tourism and sustainability defies the common perception of the environmental stewardship as a luxury item. But the strangest things come together in Benidorm. The city, after all, is also home to a church, whose bell tower integrates the staircase and elevators for a high-rise next-door, filled with vacation apartments. Ultimately, Benidorm refuses to fit into any one box. Can one even refer to such a mono-functional vacation settlement as a “city”? Benidorm has high-rises, yes, but not urbanity by a long shot — it’s too homogeneous for that. And despite — or perhaps because of — the nightclubs and boozing tourists, it’s also much too tame.![]()

-

Photo: Alejo Bagué

-

Lanz and Wolfrum call Benidorm “the old city of modernism” referring not to the many retirement-age visitors, but to the fact that the modernist idea on which the city was built is no longer contemporary. Just how right they are becomes clear when one drives a few kilometers out of Benidorm to the brand new, 80-acre golf resort, Villaitana. With its historicized medley of Mediterranean styles, this hotel village — in the center of which sits a restaurant disguised as a baroque church — is much more artificial than Benidorm could ever be. One suddenly realizes what one had with the unabashed mass-tourism of the densely packed colony of high-rises in Benidorm, when viewing its skyline hanging like a mirage on the horizon above manicured golf lawns.

![]()

![]()

Photo: Alejo Bagué

-

Grand

MassifThere must be something about concrete and mass holidays — be it under the Spanish sun at Benidorm or in the snow of the French Alps. All of a sudden we had to think of this classic Breuer-up-a-mountain: a ski resort at Flaine, near Chamonix, part of the Grand Massif, which was designed by Marcel Breuer & Associates between 1960-69 and more than holds its own against the brute nature that surrounds it.

![]() (rgw)

(rgw)Le Flaine, 2006

(Photo: Soubok / Wikimedia Commons) -

![]()

![]()

![]()

Trash Cube

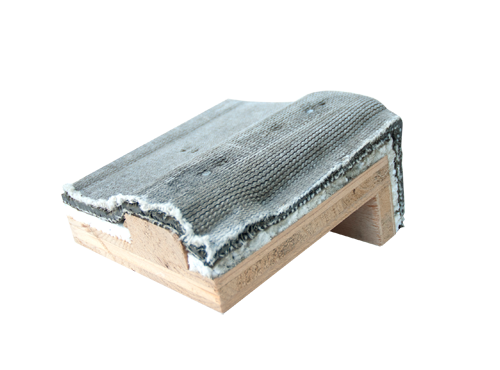

These cubic stools, by Swiss designer Nicholas Le Moigne, are each unique. The off-cuts and scraps of fiber cement from the company Eternit are condensed and sculpted to form each Trash Cube.

![]()

Photos: Tonatiuh Ambrosetti and Daniela Droz

-

Since 2009, Thorsten Klooster and Heike Klussmann have headed the BlingCrete working group at the University of Kassel.

www.blingcrete.com

Heike Klussmann

Heike Klussmann is an artist and a professor of art and architecture at the University of Kassel. Her work has been shown in recent exhibitions at the Detour Hong Kong, the KW Institute of Contemporary Art, Aedes Berlin, Heidelberger Kunstverein, and the Berlinische Galerie Museum of Modern Art. Her many honours and awards include first prize in an international competition to design Düsseldorf’s new Wehrhahn subway line, as well as an Artists Grant from Villa Aurora in Los Angeles, and the Goslar Kaiserring Grant.

www.klussmann.org

Thorsten Klooster

Thorsten Klooster is an architect in Berlin and the editor of the book Smart Surfaces — And their Application in Architecture and Design. He was a member of the Technical Science Research Group at the Fraunhofer Institute, and a design professor at the Brandenburg University of Technology in Cottbus. In 2007 he founded the firm TASK Architekten in Berlin. He has presented workshops and lectures at Akademie Schloss Solitude in Stuttgart, Università IUAV in Venice, NIEA Sidney and the University of Michigan. He is currently a referee for the 2013 IBA Hamburg’s “Smart Material Houses” competition.

www.task-architekten.de

![]()

In the Photo Booth with ...

Heike Klussmann &

Thorsten KloosterIt was a tight squeeze in our photo booth this issue: the artist Heike Klussman, the architect Thorsten Klooster, and a couple of pieces of BlingCrete - the multi-functional, light-reflecting concrete that they’ve developed, patented, and that is coming soon to a building near you …

Interview by Rob Wilson

-

Please describe BlingCrete.

Heike Klussmann: It’s a newly developed material that combines the heavy surface of concrete with light-reflecting qualities, created by embedding little spheres of glass into the concrete to about 50 per cent depth. You immediately get a unique prismatic effect, with each sphere acting as a retroreflector — meaning light is reflected away from its source at an equal and opposite angle.

-

What’s the background of the product’s development?

Thorsten Klooster:

It came out of a project Heike did for a subway station in Düsseldorf. The idea there was to use light-reflecting material but it turned out that nothing on the market complied with fire regulations, so something new needed to be developed.

Heike’s an artist, and she already used retro-reflective materials in her work, whilst I’m an architect, more on the technical and scientific side, and have written a book on smart surfaces. So we combined our two specific types of knowledge and experience in making BlingCrete.

What’s the background of the product’s development?

Thorsten Klooster: It came out of a project Heike did for a subway station in Düsseldorf. The idea there was to use light-reflecting material but it turned out that nothing on the market complied with fire regulations, so something new needed to be developed.

Heike’s an artist, and she already used retro-reflective materials in her work, whilst I’m an architect, more on the technical and scientific side, and have written a book on smart surfaces. So we combined our two specific types of knowledge and experience in making BlingCrete.

-

And the name?

HK: … of course comes from the hip-hop “bling”: shiny stuff, jewellry.

So how can BlingCrete be used? What are its applications?

HK: There are so many functional applications: for reflective road markings, industrial hazard signs, platform edges, tunnels … and in architecture, it can be used on façades, in interior design, as a way-finding system — or for small, special situations where a message or graphic needs to be seen but only at a certain point where the information is required. It can also function as a tactile system for blind people.

TK: What’s nice for designers is playing around with ideas of the visible and invisible, and the material’s special ability to change from being active to passive.

-

So a balance then between use and beauty …

TK: There’s a big discussion at the moment about art and science. But our work on BlingCrete and functionalizing concrete surfaces are practical projects that combine these two fields. What’s inspiring is having the chance to work with people from all types of fields: scientists and experts in material physics, alongside artists, architects and designers.

Our work is on materials, but we are interested in the immaterial! We only use the material as a reference to things that are more conceptual: that’s what we do.

![]()

-

Just Add Water

The small shed that Amunt Architects built for this allotment features a special construction technique: its outer shell is made of textile concrete, a material normally used in landscape design or road construction. Here it acts as a 5-milimeter-thick skin, protecting the underlying wood structure against the weather. Design-wise, the advantage is clear: this textile concrete comes in rolls and you can apply it freely, almost like throwing a soft costume over your building. It hardens only once you add water.

![]() (fh)

(fh)![]()

Photo: Brigida González

-

Concrete

Coffee LOVERSA solid hit of caffeine: that’s what this concrete espresso machine by Israeli designer Shmuel Linski doles out. “Espresso Solo” is a product for the kitchen that is unusual yet attractive and easy to use, exciting for hardcore concrete and coffee lovers alike.

![]()

![]()

-

Karine Dana, a qualified architect, was section editor at the French architecture review amc for 12 years and now works as an independent author and journalist. She currently works on a book and on a documentary film devoted to the architect Youssef Tohme in Beirut.

Born in Beirut (Lebanon) in 1968, Joe Kesrouani studied architecture in Paris and learned painting and photography on his own. In the construction of images, Kesrouani’s architectural training plays into both his photographs and paintings. He currently lives and works in Beirut where he divides his time between photography and painting. Between 1993 and 2011, he had both solo and group exhibits in Beirut, Dubai, London and Paris. www.joekesrouani.viewbook.com

Beirut’s

Saint

Joseph

UniversityText by Karine Dana

Photos by Joe Kesrouani -

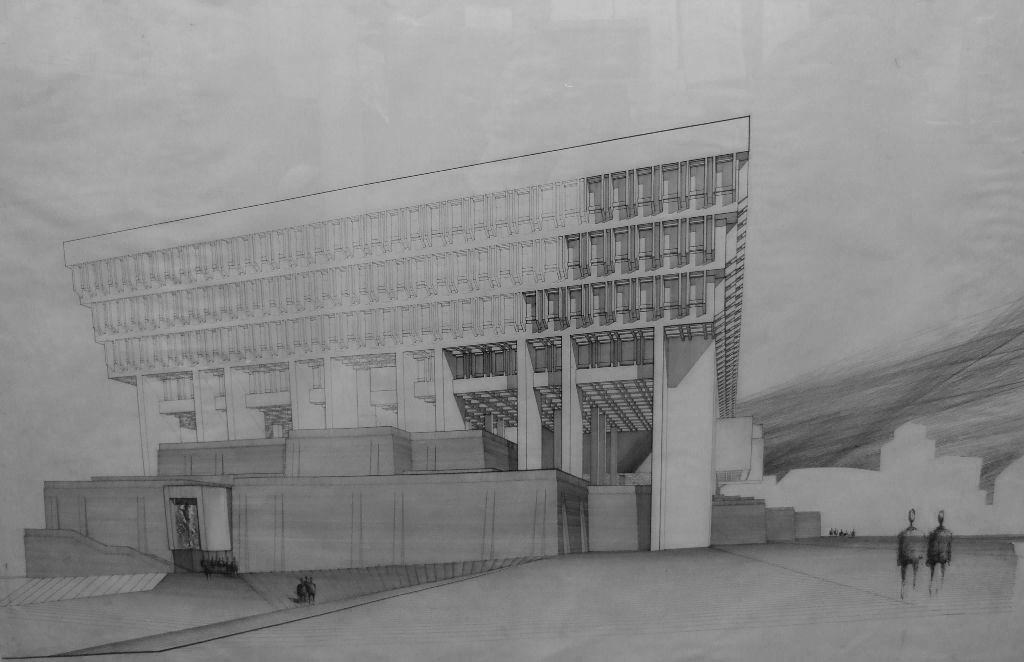

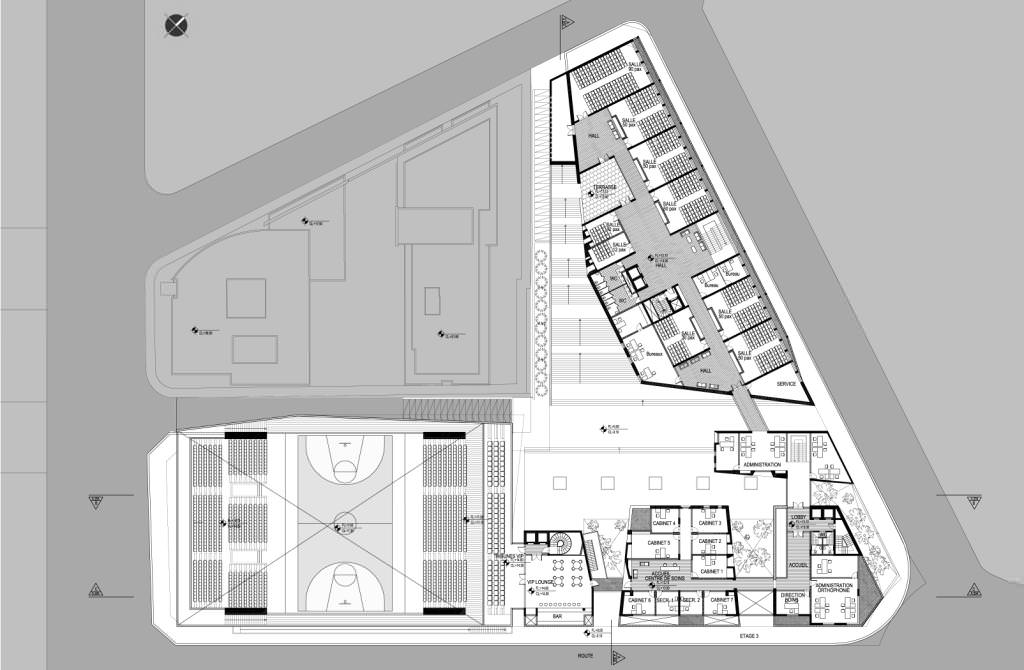

![]()

![]()

![]()

Images by 109 architects: Site plan (left), ground floor, and section through the auditorium (right)

The architecture of this new building for a Catholic university, founded in 1875 and now with approximately 11,000 students, stands out conspicuously from its surroundings. For the architect Youssef Tohme pursued his own distinct design direction, one which drew on numerous references to the recent and very checkered history of Beirut.

-

Its context is the ever-changing, seemingly arbitrary political constellations in Lebanon, which follow the whims of its chiefly urban, industrious society: one that accepts compromise, routinely giving way to economic pressures and different constraints, whilst simultaneously dominated by the fear of a renewed military conflict. After the civil war, the political system literally fell apart in the 90s, so the interests of individual religious groups, communities, and extended-family clans dominate.

The country is a narrow strip of land between the Mediterranean and the mountains, little more than 200 kilometres long and roughly 50 kilometres wide. A highway running from north to south serves as the main arterial road through the country and looks like an American commercial “strip”. This comparison epitomises how the territory is seen today: as a succession of colliding opposites, a collage. There is no broad urban planning. Frenzied construction is everywhere, especially in suburban and mountainous areas not affected by the war. The coastline is almost completely built up in places.

The conditions for construction projects are exceptional: there are no public tenders, no state-promoted housing policies — and no rules without exceptions. All that matters is land value. Construction is entirely dominated by large British firms responsible for both the off-the-shelf architecture and the large showcase reconstruction projects. Local architects have little chance to grow and develop. Their work is mostly limited to villas for rich private clients.![]()

-

![]()

A handful of architects nevertheless seek to draw upon the thrilling 1950s and 1960s architectural legacy and to reinvigorate a discourse on architecture and urban design that had all but come to a standstill in Beirut. This is especially true of Pierre El Khoury, Bofill student Nabil Gholam, and Bernard Khoury (the last two trained abroad and opened Beirut offices years ago). Their works represent a profound, sometimes metaphorical or symbolic engagement with the experiences of the war.

This group also includes Youssef Tohme, who has studied and worked in Beirut and Paris, even though his debut project, discussed here, has entirely different dimensions of scale and scope. For Tohme, Lebanon is a cosmos of almost solely reflexive responses to external stimuli: destruction, rebuilding, and isolation. His preferred conception of Lebanon is of a country that has grown through fractures and scars. In 2004, with Lebanese practice 109 Architectes he led the design teamof the new building for Beirut’s Saint Joseph University (USJ: Université Saint-Joseph de Beyrouth). The project’s bold design: the unusual internal organization and idiosyncratic expression of its raw Brutalism initially made it difficult to gain acceptance from the client and the contractors. But by integrating the city into the project, extending public space vertically, and the rational arrangement of functions in the lower levels, including a four-story underground garage, he ultimately succeeded in convincing them.

“Architecture has an especially precarious status here,” says Tohme. “You must be careful, and always use clever tactics: show restraint, assert oneself, talk, say nothing. I fear the new generation of architects, trained abroad, will simply import ready-made images. We must act more prudently, especially now that Beirut is being built anew. In contrast to other cities, Beirut’s identity is extremely fragile.”»In contrast to other cities, Beirut’s identity is extremely fragile.«

Youssef Tohme

-

![]()

![]()

»The empty space is a direct expression of freedom.«

Youssef Tohme -

Tohme uses the USJ campus project to pursue key issues that he explores in his other projects: How can emptiness be formulated architecturally? What determines the relationship between people and built enclosures? Can different functions be superimposed? Additionally, something unexpected — an almost, a maybe — is a common element in his designs. Tohme wants to take risks. The same is true of the material he selected for the USJ project: in-situ concrete; a material that is both ambivalent and enables everything; one that offers a whole range of possibilities. “I use concrete to pose questions — not as a medium to obtain a certain form or aesthetic.”

The site

USJ’s Campus of Innovation and Sports is sited directly on the old demarcation line that divided the city during the civil war into the Christian east and the Muslim west. The building complex appears monumental yet open at the same time. A total of 60,000 square meters of usable floor area is packed onto a 6,000 square meter lot built up to its edges, but which still manages to create new urban spaces. Tohme’s design is the opposite of a freestanding building.

The complex is convincing due to its urban qualities. In the middle of the high-security diplomatic quarter of the Rue de Damas, where nothing of the old urban structure survives, it is an autonomous entity but without appearing monolithic. The deep recesses and rough edges connect the heterogeneous architecture of the immediate neighborhood into part of the design. The university also required areas for variable use, and themes of appropriation and encounter are addressed in the “empty space.” An attempt is made to experiment with public space and ask what togetherness could look like in everyday terms.![]()

-

![]()

![]()

»The architectural output in Lebanon has become ensnared by questions of formal nature and of superficially symbolic importance.«

Youssef Tohme -

»I have the feeling that with prefabrication, much of the emotionality of building is lost.«

Youssef Tohme -

In Beirut, this concept of public space can be read as a form of resistance, as the city effectively lost its public places as a result of the civil war. For Tohme, it is fundamentally important to formulate, through architecture, the issues pertaining to this that arise today. In a society where all the space is privatized, the state has no control whatsoever anymore, and individual needs are the sole measure of things, how can one reflect upon the basic requirements of a community?

An urban respite

Tohme places a public space at the heart of the campus; it is almost an interior space, around which he centrally organizes the campus. An unusual sense of peace dominates here: the otherwise ubiquitous noise of the city can only be heard in muted tones. The space of the court continues upward by means of an exterior staircase, purposefully wide to let people sit undisturbed upon it.![]()

![]()

-

![]()

-

The stair leads to the roof terrace, where one can stroll, play sports, talk in peace, or simply hang out — a place for everything, open to all.

This three-dimensional public zone can be seen as a model for a spatial continuum without barriers. The opportunities this place offers are precious in a city still traumatized by the past. With this spatial experience, Tohme wants to encourage contemplation of the principle of non-exclusion. The spatial strands intersect or connect, compete with one another, and/or overlap. A complex structure emerges, one that perhaps comes close to a new form of “libanéité”, of being “Lebanon”.

“Working out such a spatial mood is a clear alternative to the obsession with architectural style that ordinarily occupies international architecture,” says Tohme. “The architectural output in Lebanon has become ensnared by questions of a formal nature and of superficially symbolic importance. The question of the spatial effect seems more fundamental and real to me. It is about the sensory experience, about the creation of a system of references, a system of emptiness resulting from the war. So I prefer working with the empty space than making purely visual stipulations. It is a direct expression of freedom.”

Brutalism, Concrete and Lebanon

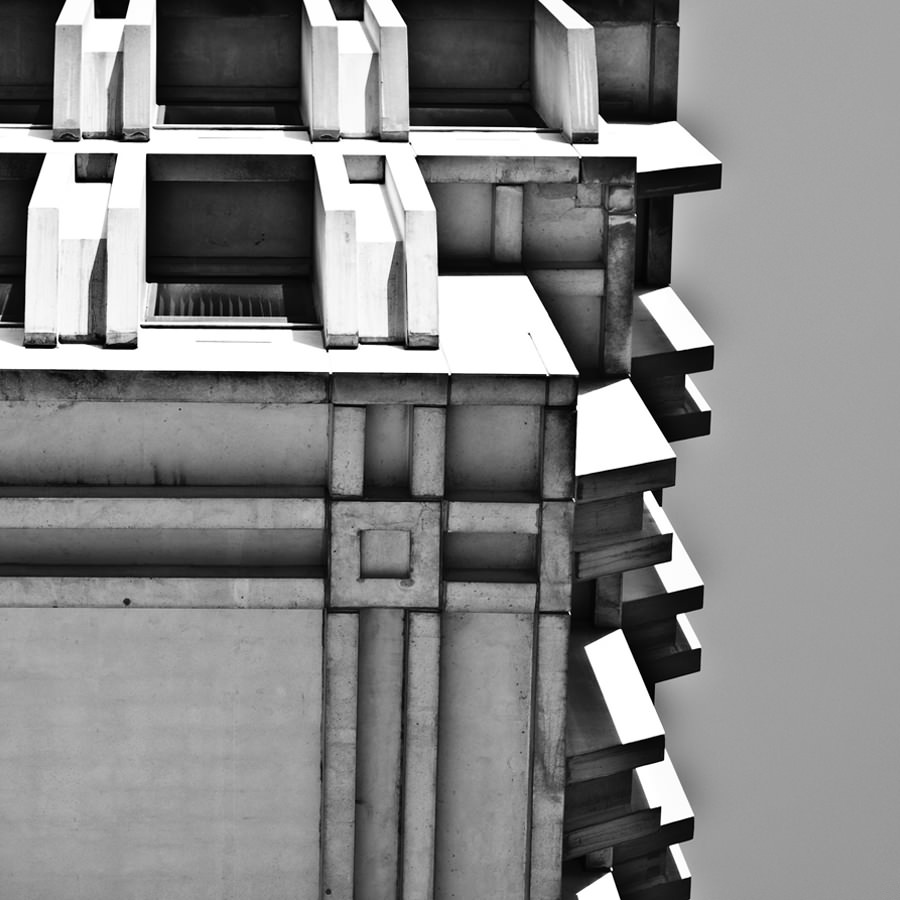

The relatively small lot sizes and the great importance the architect attaches to public space imply the campus’s vertical organization. As if one had thoroughly shaken up what was originally a monolithic block, the building is comprised of three parts that are, in turn, further divided into smaller units and interconnected via footbridges.

The first block, to the south, contrasts starkly with the others due to its façade cladding of lightweight polycarbonate panels.![]()

-

The block contains stacked sports facilities: on the ground floor an open space, above the gymnasium and above that the swimming pool. At the very top, on the roof terrace, is a basketball court. In the second block, above the glazed auditorium and the cafe on the ground floor, are a music hall and seminar rooms, as well as a chapel at the very top. The ground floor of the third block contains the central entrance foyer and a large lecture hall. Above these are the library and more seminar rooms, a reading room, and a rooftop restaurant.

The complex organizational structure, in which uses are repeatedly superimposed to create tensions between them, follows a constructive logic that deviates entirely from conventional layouts. Thus there is no discernable pattern in the system of load-bearing walls and columns — with the possible exemption of the grid in the lecture rooms. It seems as if the functionalprogram has been assembled into a seemingly endless spatial form that could just as well have already existed before. This impression, that the USJ might have always stood here, is reminiscent of the Brutalist architecture of Jacques Kalisz, or Lina Bo Bardi’s SECS Pompéia in São Paulo.

Precisely because the individual volumes cannot be read in the untreated in-situ concrete of the exterior façades, one gets the impression of a continuous public space. In Beirut, where everyone swears by natural stone, exposed concrete is regarded as a materia non grata. The solid concrete walls are slit, pierced, and broken up, thus putting customary readings to the test. Here, the concrete becomes a material of ambivalence, a building material for a cast landscape that refuses to give the viewer even the slightest hint of functional assignments. The architects have tested the limits of formwork and casting techniques, thus raising our awareness of them.»I use concrete to pose questions — not as a medium to obtain a certain form or aesthetic.«

Youssef Tohme -

That these concrete walls, reaching heights of up to 25 meters, were cast in-situ at all is a testament to the craftsmanlike virtuosity of a local construction company. The southeast façade looks like it has been riddled by bullet holes. It is an intentional gesture, very close to aestheticizing the horrors of war, but which is offset by the compelling visual effect.

This principle of experimentation and the lack of perfection from working in-situ also relates to the material itself. The exposed concrete does not have a consistent colour throughout. In some places it tends toward pink, as the quarry that supplied the white sand ceased operations during the construction and the sand then imported from Cyprus had a significantly more reddish pigment. For Tohme, the resulting variation in the colouring reflects the economic reality in Beirut, which can always change in an unforeseeable way. “I have the feeling that with prefabrication, much of the emotionality of building is lost”, says Tohme. “That particularly becomes apparent at a large scale. The in-situ concrete tells much about Lebanon and about the conditions that prevailed during the construction.”

The civil war and architecture are constant companions. This building complex for a post-traumatic Beirut contradicts that which Yona Friedman dared to imagine for Berlin: that war would create a new awareness for the uselessness of the static. For Youssef Tohme, the war has shown that the static and durable is not obsolete. His fundamental question aims to discover how our world could succeed in enduring. Seen in this light, his architecture in the heart of the city is a defiant argument against war — and also against the current policy of reconstruction.![]()

![]() Youssef Tohme on site during the construction of USJ campus. All photos: Joe Kesrouani.

Youssef Tohme on site during the construction of USJ campus. All photos: Joe Kesrouani. -

Double Spiral

You never know what you will encounter on a boat-ride adventure in the rain in Amsterdam. In this case, it was an exquisitely beautiful piece of concrete architecture. The Europarking building is located on the Nassaukade in Amsterdam. Designed and built between 1966-71 by Piet Zanstra, Ab Gmeg Meyling, and Peter de Clerq Zubli, the structure is made with in-situ concrete, in a double-spiral design. The bottom floor accommodates buses, and the seven upper stories are for cars. Unsurprisingly, the building is popular with skaters and bikers taking a recreational spin in the twisted architecture. In a striking turn, at night the headlights of cars cast a spiraling glow that moves up and down the building as vehicles ascend and descend. In 2007, Spencer Tunick selected it as the site for one of his installations, with massed naked volunteers making an equally as arresting spectacle.

![]() (jb)

(jb)Photo: Naked volunteers pose for Spencer Tunick in the Europarkring building, June 3rd, 2007. (Photo: Reuters/Koen van Weel)

-

![]()

A Brutalist Love Story

Boston City Hall

Text by Jessica Bridger

![]()

-

A proud Bostonian walks the freezing, icy grey streets with Northern reserve: impassive, quietly powerful and with a forbidding air. Boston City Hall stands stationary at the heart of the city with the same sort of harsh character. In Boston, we love with an austerity that belies an inner passion, and some of our best modernist buildings are expressive of this cultural commonality.

There is perhaps no brutalist masterpiece that is by turns more reviled and loved than Boston City Hall. The building was built as the result of a competition won by the architects Gerhard Kallmann and Michael McKinnell in 1962, and the public’s judgment of the building has oscillated between enthusiastic admiration and absolute hatred in the intervening decades. The hulking concrete volume of the building sits on a plaza like a giant red-brick fantasy roller-rink in the middle of Boston’s urban core. The failure of this public plaza is undeniable: the treeless brick expanse is boiling hot in summer and dangerously slick in Boston’s harsh winters.![]() All photos: Mark McLean, 2012

All photos: Mark McLean, 2012 -

![]()

![]()

Drawings: Courtesy of Friends of Boston City Hall»The public’s judgment of the building has oscillated between enthusiastic admiration and absolute hatred.«

-

The showpiece of the building — and the section of the three-part concrete and brick building that most people identify as Boston City Hall — is its concrete mass, rising triumphantly out of the sea of brick. These parts of Boston City Hall were designed to demonstrate the importance of public political processes and politicians in Boston. The interior of this space has a central atrium, which, prior to 2001’s security alterations was fully open to the public, who could gaze upon their elected officials (on their way to pay parking tickets on one of the floors below).

The “success” of this building is a complicated issue. The exterior is striking; the interior, though rounds of renovations which have made a warren of walls, is stifling. Though brutalist architecture was somewhat popular during the 1950s and 1960s on the Eastern Seaboard, it was never embraced by an adoring public. The style is tied to early modernist construction practices where in-situ concrete — poured onsite, commonly into wooden formwork — was in Brutalist architecture left in a largely unfinished state, unthinkable before. Naked concrete: how outré! About half of Boston City Hall was constructed in-situ and half from pre-cast![]()

»Form, in this case, seems to endure more sustainably than function.«

![]()

-

components. The grain of the casting form is visible in many cases, almost like a patina of the organic over an undeniably constructed mass.

Over the years, the organization Friends of Boston City Hall has championed the building against critics and supported calls to refurbish and substantially remodel. Calls to tear the building down or move its functions elsewhere have been voiced repeatedly and with some stridency over the years, and a plan to retain the structure but move city hall was halted due to the recession. For now and the foreseeable future it is civic business-as-usual in Boston. Boston newspapers still vacillate between reporting on the dismal interior conditions of the building and reporting on residents’ love of the structure. Regardless of its pragmatic function, the building has an iconic presence in the centre of the city. Form, in this case, seems to endure more sustainably than function. Hard-edged Bostonians, loving to hate what’s theirs, have adopted what many see as an ugly stepchild with a grudging pride, and in the end, even a bit of love.![]()

![]()

»There is perhaps no brutalist masterpiece that is by turns more reviled and loved than Boston City Hall.«

-

Heal Thyself!

A concrete that mends itself? Well perhaps. Microbiologist Henk Jonkers working alongside concrete technologist Eric Schlangen at Delft Technical University have added dehydrated limestone-producing bacterial spores to a concrete mix. If the concrete should crack, allowing in water — which over time erodes the concrete and corrodes any exposed steel reinforcement — presto! these spores wake up and start industriously producing limestone to plug the cracks. But don’t get too excited: it’s still undergoing tests and any commercial application is two or three years off.

![]()

Henk Jonkers explaining the concept of Bio-Concrete (Video: TU Delft).

-

Concrete

Editor: William Hall

Essay by Leonard Kohen

240 pages, Hardback, 290 x 250mm, EnglishForms of Practice: German-Swiss Architecture 1980-2000

Ed.: Irina Davidovici

281 pages, softcover, 17 x 24 cm

EnglishHow to Make a Japanese House

Edited by Cathelijne Nuijsink

Designed by Sander Boon

Paperback, 328 pages, 16 x 24 cm

NAi Publishers, 2012

Bookmarked

![]()

This book contains a far richer mix than its coffee-table looks suggest: an intelligently-themed, eclectic selection of projects, both familiar and obscure. The projects are presented through archive and contemporary images with short, enlightening captions, all contextualized in a thoughtful essay by Leonard Koren that grounds a personal, physical experience of concrete. (RW)

![]()

Whilst the German-Swiss architecture phenomenon is not a new subject, this rigorously-researched and intelligent tome provides a fresh step back, divining the magic ingredients that have made it such an influential trend — traced through Swiss-ness, the ETH Zurich, and a detailed analysis of seminal projects. (RW)

![]()

No, this is not a construction manual. It's a selection of 21 radical, single-family houses in Japan, accompanied by 21 entertaining and informative interviews with their architects (including Sou Fujimoto, Kengo Kuma, and Kazuyo Sejima), illuminating their concepts in a way that makes you want to read the next interview. And the next. (FH)

-

Edge City: Driving the Periphery of São Paulo

Editor: Justin McGuirk

Available for Kindle and iPad

Strelka Press, 2012Sweet and Salt: Water and the Dutch

Tracy Metz, Maartje Van Den Heuvel

296 pages, Softcover, 23 x 28 x 2.3 cm

NAi Publishers, 2012Why We Build

Rowan Moore

416 pages, Hardcover, 23.4 x 15.3 cm

English

Picador, 2012

![]()

A well-written travelogue can provide an intimate understanding of place. Justin McGuirk’s new story of a day-long road trip around São Paulo’s perimeter is a perfect encapsulation of the “unstoppable” city. Taking us on a tour of various social housing typologies — the self-built shack to the modernist block — McGuirk combines keen observations and personal anecdotes with dense historical and socio-cultural information. (EW)

![]()

The Dutch are masters of managing the relationship between land and water. The constructed nature of the Netherlands has defined the country for centuries, in everything from economic to social terms. Tracy Metz and Maartje Van Den Heuvel's new book traces the country’s history into the present, taking an interdisciplinary approach to this pressing issue that will eventually affect us all. (JB)

![]()

Money. Power. Respect. In his bluntly titled book, Why We Build, Rowan Moore chronicles the money and power — along with sex and other base human motivations — behind a diverse range of architecture projects throughout the history. Personal yet global, he takes us from the Parthenon to the World Trade Center, from Adolf Loos to Lina Bo Bardi, in an entertaining, enlightening, and accessible book for everyone. (JB)

-

Next

Apocalypse Soon!

Last things and fresh starts

![]()

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Form follows feminine.«

Oscar Niemeyer

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents

This and following photos: Miguel Loos

This and following photos: Miguel Loos

Youssef Tohme on site during the construction of USJ campus. All photos: Joe Kesrouani.

Youssef Tohme on site during the construction of USJ campus. All photos: Joe Kesrouani.

All photos: Mark McLean, 2012

All photos: Mark McLean, 2012