-

Magazine No. 07

Off Places

-

No. 07 - Off Places

-

page 02

Off Places

-

page 03 - 04

Editorial

-

page 05 - 13

Furka Pass

A closed hotel, nothing much to see – yet Jenny Holzer, Sean Connery, and Rem Koolhaas have all been here …

-

page 14 - 16

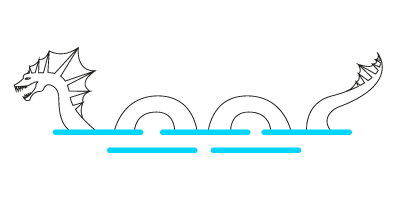

Spots on the Map

The deserted islands of the Mediterranean

-

page 17 - 33

Strangely Familiar

Todd Saunders and the Architecture of Lonely Places

-

page 34

Spanish Colors

Young Spanish architects bring color to a shrinking city in Bavaria

-

page 35 - 44

Revelations of atelier le balto

Cultivating beauty in the off-spaces of Berlin

-

page 45 - 46

Secretly Public in NYC

-

page 47

Hidden Hotel

-

page 48 - 60

The Mystery Train Station of Canfranc

Marc Chagall, Nazi Gold and Doctor Zhivago! It all comes together ...

-

page 61 - 65

In the Photo Booth with...

Gottfried Böhm

-

page 66 - 69

Bookmarked

-

page 70

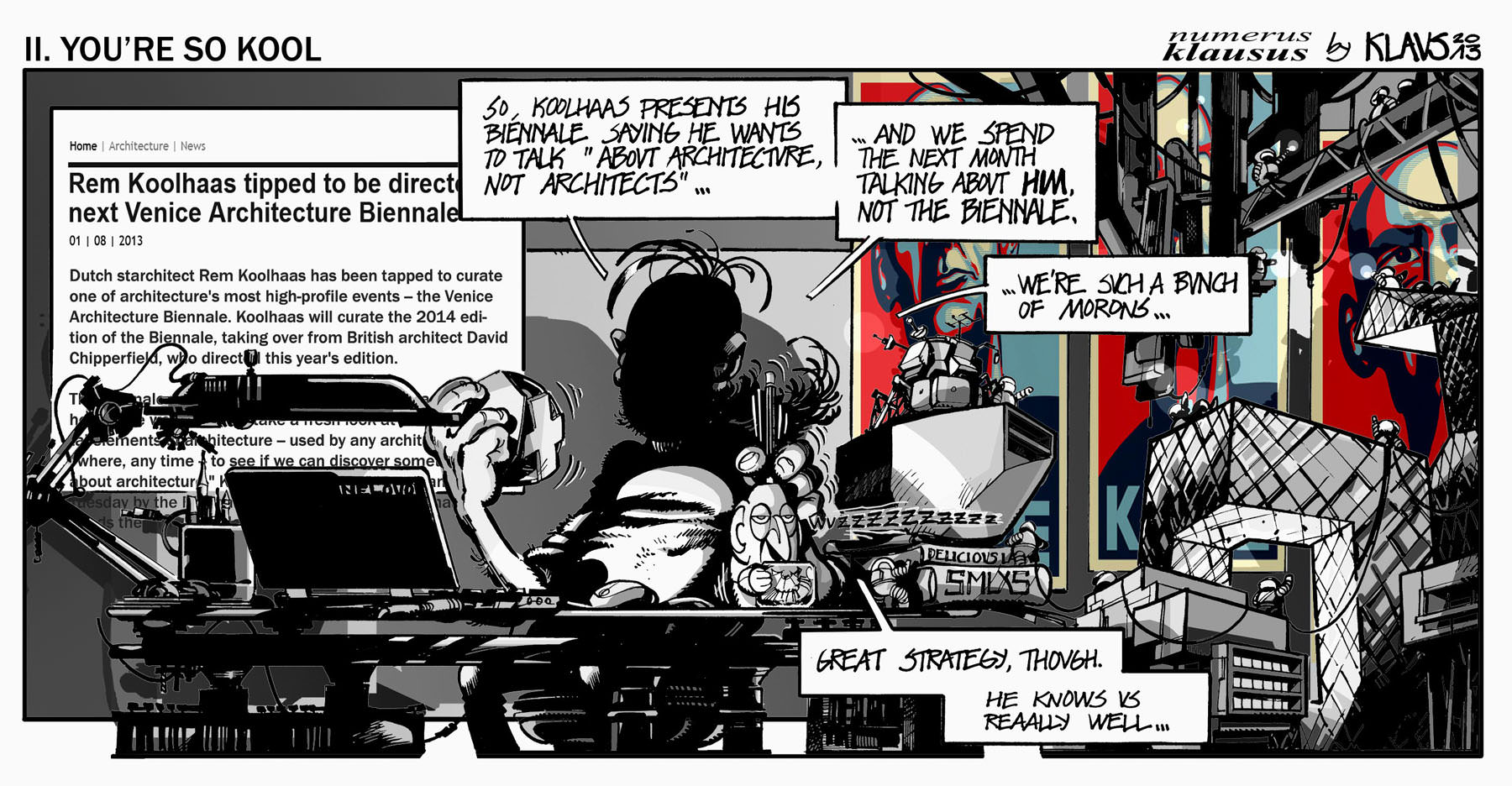

Klaustoon

II. You're so Kool

-

page 71

Next

Culture & the City

-

-

Uncube's editors are Elvia Wilk, Florian Heilmeyer, Jessica Bridger, and Rob Wilson. Uncube is based in Berlin and is published by BauNetz, Germany's most-read online magazine covering architecture in a thoughtful way since 1996.

Whether a quiet place of contemplation, a secret hideaway, a forgotten place, or simply burying yourself in a book, going to an “off place” is sometimes the only way to get yourself back on track.

But does it need infrastructure, buildings, architecture? If so, what can be built that doesn’t destroy what you went there for in the first place? As Todd Saunders puts it in our interview with him: “Out in the landscape, you really appreciate things. You shouldn’t actually build there. You can’t really improve it.”

We say: go for it. Get off the map. Maybe you won’t want to get back at all after reading this issue packed with fantastic off spaces – from the far-flung to the under-the-nose – and an exciting debut feature: Klaus’ Kube, our new monthly cartoon – pricking an architectural bubble or two.

Have a good trip through the issue!

The Editors![]()

![]()

![]()

Cover Photo: Bent René Synnevåg

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

-

Furka Pass

A closed hotel, nothing much to see – yet Jenny Holzer, Sean Connery, and Rem Koolhaas have all been here …

Text by Anneke Bokern

Photos by Miguel LoosIt barely looks like one, but this is an early Koolhaas. Back in 1988, Rem designed a new entrance and terrace for the Furka Hotel – four years before OMA got famous for the Kunsthal Rotterdam.

-

![]()

The weather is terrible. It’s freezing cold and rainy, the clouds hang low, and there’s snow in the valley. Bundled in an anorak, I stomp up a rocky slope, further into the mist. What the hell am I doing here?

I’m seeking art. My little expedition began at Hotel Furkablick, at the highest point of Furka Pass in the Swiss Alps, 2,436 meters above sea level. The description from only two pages from Rem Koolhaas’s infamous tome S, M, L, XL was all it took to lure me to this place at the end of the world. The pages describe the conversion of the Hotel Furkablick restaurant, which was conceptualized by Koolhaas in 1988. Not that I’m crazy about the early concept: much more exciting is the hotel itself, and its legendary, secluded location.

»What the hell

am I doing

here?«

-

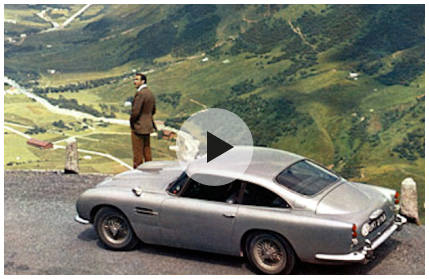

In the year 1789, royal French geographer François Robert called Furka Pass “une horrible traversée.” In 1964 a car chase was filmed here for the movie Goldfinger, and in 1983 Marc Hostettler, a gallerist from Neuchâtel, began organizing an annual land art event in the Pass. Hostettler was the hotel owner who commissioned Koolhaas with the design. “He ran the art program as well as the hotel, apparently absent-mindedly oscillating between the two roles,” recalled Koolhaas. “When he invited three architects to a symposium, none came. A year later, when I was a tourist passing through, we discussed a “modernization”: a minimal intervention through which the hotel would receive a real restaurant, a kitchen, a dining room, an entrance, and a viewing platform, without changing any of the rest.” The reconstruction was completed in 1991. Shortly thereafter, the Land Art Festival breathed its last breath, and nothing else has been heard of the hotel since - until now.

![]()

![]()

![]()

This place has seen better times, as the tourism brochure and the old postcard with “Greetings from the Furka Pass” prove. In 1964, James Bond (Sean Connery) chased Tilly Masterson (Tania Mallet) along the serpentines of the Furka Pass, also passing the Furka Hotel.

-

![]()

Today, most of the striped shutters are closed. Of the former balconies, only the wrought-iron balustrades remain.

![]()

According to the mustachioed man in the natty suit, nothing has changed in the rooms since the hotel’s opening in 1900.

We spiral up the Pass on a cloudy day. As the hotel finally comes into view, it seems deserted. The old building, jammed between the street and a slope, has certainly seen better days. Most of the striped shutters are closed, and all that remains of the former balconies are the wrought-iron balustrade grills, clinging to the walls. A steely, funnel-shaped portal, unmistakably one of Koolhaas’s interventions, forms the entrance to the restaurant. Surprisingly, it’s open. The only sign of human life in the low, rustic room is a mustachioed man in a sweater-vest, waiting for guests behind an excessively avant-garde concrete bar. He looks as if he’s been standing there for years. Outside, wafts of mist drift through the valley. It reminds me of The Shining. What a splendid place. I want to stay here.

When I ask for a room, the man explains that the hotel is closed. Actually, it’s more than closed: it’s a sealed time capsule. “Nothing has changed in the rooms since the hotel’s opening in the year 1900,” he says quietly. “They all remain in their original condition, with chamber pots and washbasins. Because the facilities are too old-fashioned, we haven’t received any star guests, and we therefore can’t charge enough money to make a profit from overnight stays. The Pass is only open three months of the year. And it’s as good as impossible to find employees who want to work up here.” -

![]()

»It reminds me of

The Shining. What

a splendid place.«![]()

-

It’s not entirely true that nothing has changed. Some of the artists whom Hostettler invited to his festival have left behind traces in and around the building. But many are so subtle that you hardly notice them – you really have to look closely: the white-and-green stripes on the shutters are works by Daniel Buren; Paul-Armand Gette wrote the elevation of “2430” on a window in the restaurant; Glen Baxter embellished the walls of room 35 with a mural. A map of the area, which you can buy at the bar, depicts the locations of all of the works that artists such as Richard Long, Roman Signer, Panamarenko, Per Kirkeby, and Lawrence Weiner have created over the years. “No, they aren’t all still there,” says the barman. “Nature has reconquered much of it. I certainly don’t know which ones can still be found. Not many people ask.”

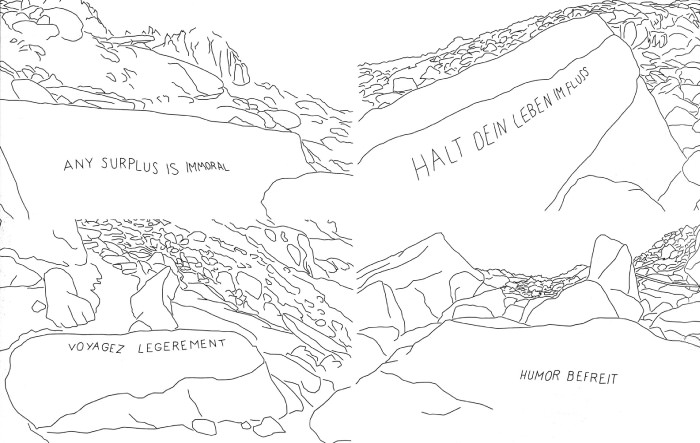

Most of the works are gone, as quickly becomes apparent – they’re overgrown, weather-worn, or washed away. After spending a while, without success, trying to find the works that are supposed to be closer to the hotel, I decide upon another strategy; now I look for those most likely to have survived a decade and a half in an alpine climate, a series of “truisms” in four languages that Jenny Holzer engraved into some rocks in 1991. An hour later, I find myself on a little trail, high above the hotel. I scour the rocks for inscriptions and feel like a child on a scavenger hunt.

As it begins to drizzle, I gradually lose interest. Then I suddenly see it: “Halt Dein Leben im Fluss,” barely legible on a rock near a small brook. A step further is “Voyagez légèrement,” followed by “Humor befreit” and some other multilingual phrases spread across a radius of 200 meters. Until now, I had only known Holzer’s Truisms as LED light-displays in museums, but the lonely, rough landscape of Furka Pass lends them a very different effect. As rock inscriptions, they suddenly suggest an ironic version of the Ten Commandments.The steel, funnily-shaped portal, unmistakably an element of Koolhaas' redesign, leads into the restaurant of this time-capsule.

-

»Boredom makes you

do crazy things.«There is art everywhere but you have to look very closely: the striped window shutters are an artwork by Daniel Buren.

-

![]()

![]()

Back at the hotel, I warm myself up with a cup of tea, pleased with myself and my discoveries. That is, until I see a photo on the postcard stand of one of Holzer’s rocks, which I apparently missed. “Boredom makes you do crazy things,” it says. Sometimes that’s also true of art.

![]()

For adventurous art maniacs only: a series of Jenny Holzer's “truisms” that are engraved in stones spread along a trail high above the hotel. Most of the other artworks around the hotel have been “reconquered” by nature.

-

![]()

-

Spots•on•the•Map

The deserted islands of the

MediterraneanText by Elvia Wilk

The Habibas islands, about 12 km from the Algerian coast, are of volcanic origin. There are no permanent settlers, just a small jetty, a lighthouse dating from 1879, and a few small buildings. (Photo: © Desertmed 2009)

-

Desertmed is a collective of artists, architects, writers and theoreticians who have been cataloging and documenting the deserted islands of the Mediterranean since 2008. These patches of earth rising up from the sea are technically territories of various nations, but in Desertmed’s images and audio they don’t look or sound like they belong to anyone – or any time.

Besides their spectacular natural landscapes, the rocky outposts host the remnants of former inhabitation: prisons, military outposts, private homes of the rich. The islands’ roles have changed and overlapped over time, cropping up or vanishing from maps according to their shifting political importance. Today, in the context of growing populations, rapid economic fluctuations, and rising sea levels, they’ve become strange icons of timelessness, a “state of![]()

Zembra is a 432 metre tall rock formation off the Tunisian coast. Its cliffs make it almost a natural fortress with only one ancient port on the southern coast. It is currently used by the Tunisian army. (Photo: © Desertmed 2009)

![]()

-

Desertmed is an ongoing interdisciplinary research project by Amedeo Martegani, Armin Linke, Giulia Di Lenarda, Giovanna Silva, Renato Rinaldi and Giuseppe Ielasi. The Desertmed project was most recently exhibited at the NGBK in Berlin.

Quote taken from project text by Amedeo Martegani.

a permanent, almost meteorological flux, of the appearance of the void, the desert, the social gap, the ungovernable zone, as a place of the soul.”

Greece has recently put its abandoned islands up for sale. Even the island of Skorpios, once the Onassis family’s private abode, is now on the market for 200 million dollars. Add to that equation the new shipping routes and infrastructural changes in the Mediterranean, and it seems like many of these islands will soon become less deserted. With them, the dream of the remote island utopia – dating from Robinson Crusoe to Gilligan’s Island – may become as remote as the islands once were.![]()

![]()

The Galite Islands are a rocky archipelago and belong to Tunisia. Their location between Tunisia and Sardinia make them a strategically relevant point in the Mediterranean Sea, although their harsh landscape can hardly be called “welcoming”. (Photo: © Desertmed 2009)

-

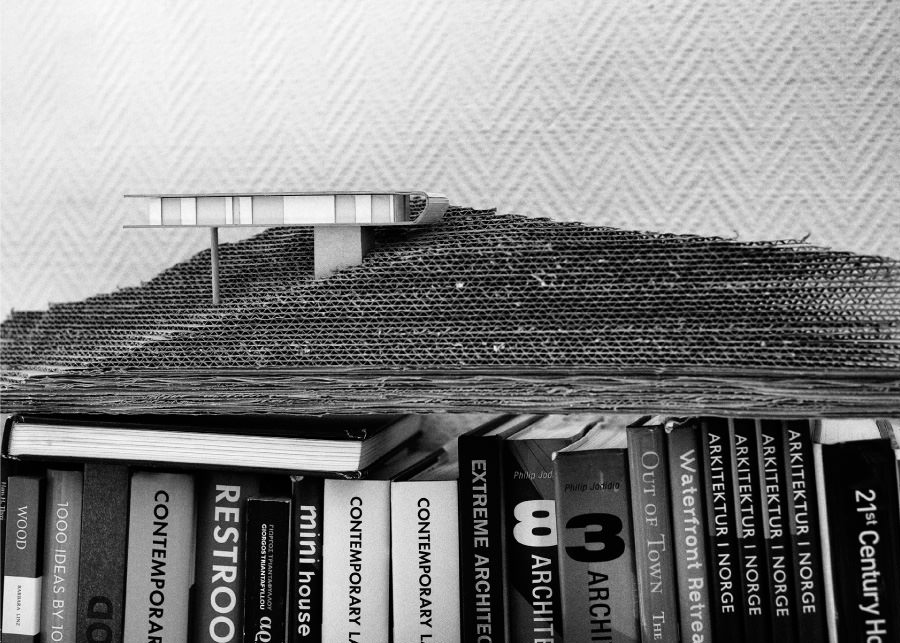

Squish Studio, Fogo Island, Newfoundland, Canada, 2011.

![]()

![]()

Interview By Rob Wilson

-

Todd Saunders is best known for a number of small exquisite buildings and structures that sit like specs of pristine ur-architecture amid vast wild landscapes – from Norway’s west coast to his celebrated series of Fogo Island studios, off Newfoundland. He grew up in Canada, studied ceramics and environmental town planning at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design in Halifax (he had originally wanted to study sculpture and ceramics but says he “didn’t have the balls to do it”), followed by a Masters in Architecture at McGill University in Montreal. In 1998 he opened his office in Bergen – which is Norway’s second largest city, but somewhat an off-place in many ways.

So when we caught up with him, we asked about this distinctively “off-space” oriented trajectory of his practice thus far.You’re from Canada, how did it come about that you opened your office in Bergen? It’s somewhat off the beaten track for an architect looking to relocate abroad!

Well, yes. It’s in the middle of frigging nowhere. But the city is so nice in itself. What I always say is that it’s a good place to live but a shitty place to work – except for my colleagues of course! – there’s nothing going on architecturally here. But it does have all the advantages of living in a small town: people watch out for one another, and it’s easy to get out into nature. I first visited Norway when hitchhiking to Moscow as a student and then decided to come back. I was going to live in Oslo but then I came up here as it fit my lifestyle – I could go kayaking and do backcountry skiing, race mountain bikes – though of course now that I have kids I don’t do any of that stuff any more!

![]() Todd Saunders. (Photo: Jan Lillebø)

Todd Saunders. (Photo: Jan Lillebø) -

But originally I was going to try it out for six months. At first it was like survival, I had no work but I had a woman here, so I realized I wanted to stay.

I was teaching at the architecture school in Bergen and trying to build up a practice. I was designing and doing anything that I could get my hands on – like playgrounds – and also working with a carpenter every second week, doing odd jobs, because I didn’t know how long I was going to be here. I built a chicken house, and worked with the students at the architecture school, and all the time I was learning all this stuff – how to build in Norway, the price of material – without realizing I was learning. So I pieced together a living and for the first few years I was super-happy. Of course when I look back at it, it was a shit load of work.![]() Corner of Todd Saunder’s office. (Photo courtesy Saunders Architecture)

Corner of Todd Saunder’s office. (Photo courtesy Saunders Architecture) -

![]()

![]()

»At first it was like

survival, I had no

work but I had a woman

here, so I realized

I wanted to stay.«Hardanger Retreat, Kjepsø, Hardanger Fjord, Norway, 2003

-

Lookout point, Aurland, Norway, 2005. (Photo: Nils Vik)

-

So how did you start your architecture practice?

Well I met another guy who was in the same situation: Tommie Wilhelmsen. We were frustrated young architects with no projects. So we saved the money from a few commissions doing small stuff, then bought a piece of land and built this cabin up at Hardanger for ourselves, working with one of our students who was a carpenter. Then we got a few pictures taken by Bent René Synnevåg, who we’ve worked with on all our projects since – he just went up there for an hour or so, didn’t really take it too seriously,. But it was at the time when the media and the internet were coming together and it was suddenly easier to get things out.

So the project got wide coverage and acted as an amazing calling card?

Yes, the funny thing in retrospect is: if there had been no internet, we probably wouldn’t have gotten that much exposure. We would just have been these recluses living out on the west coast in the middle of nowhere – no one would ever have known about us! Yet suddenly it was possible. We could be based anywhere and work anywhere. We just did a house in Polynesia and we’re doing a really nice project in Istanbul which is quite large, and a hotel in Canada – all this stuff because people read about us.

So after the Hardanger Retreat came the Aurland Lookout…

Yes. When we were doing Hardanger we got a call to compete for a lookout structure on one of the national tourist routes. They invited all the established architects and then they invited us as the young unknowns – and we won!

![]() Lookout point, Aurland, Norway, 2005

Lookout point, Aurland, Norway, 2005 -

![]()

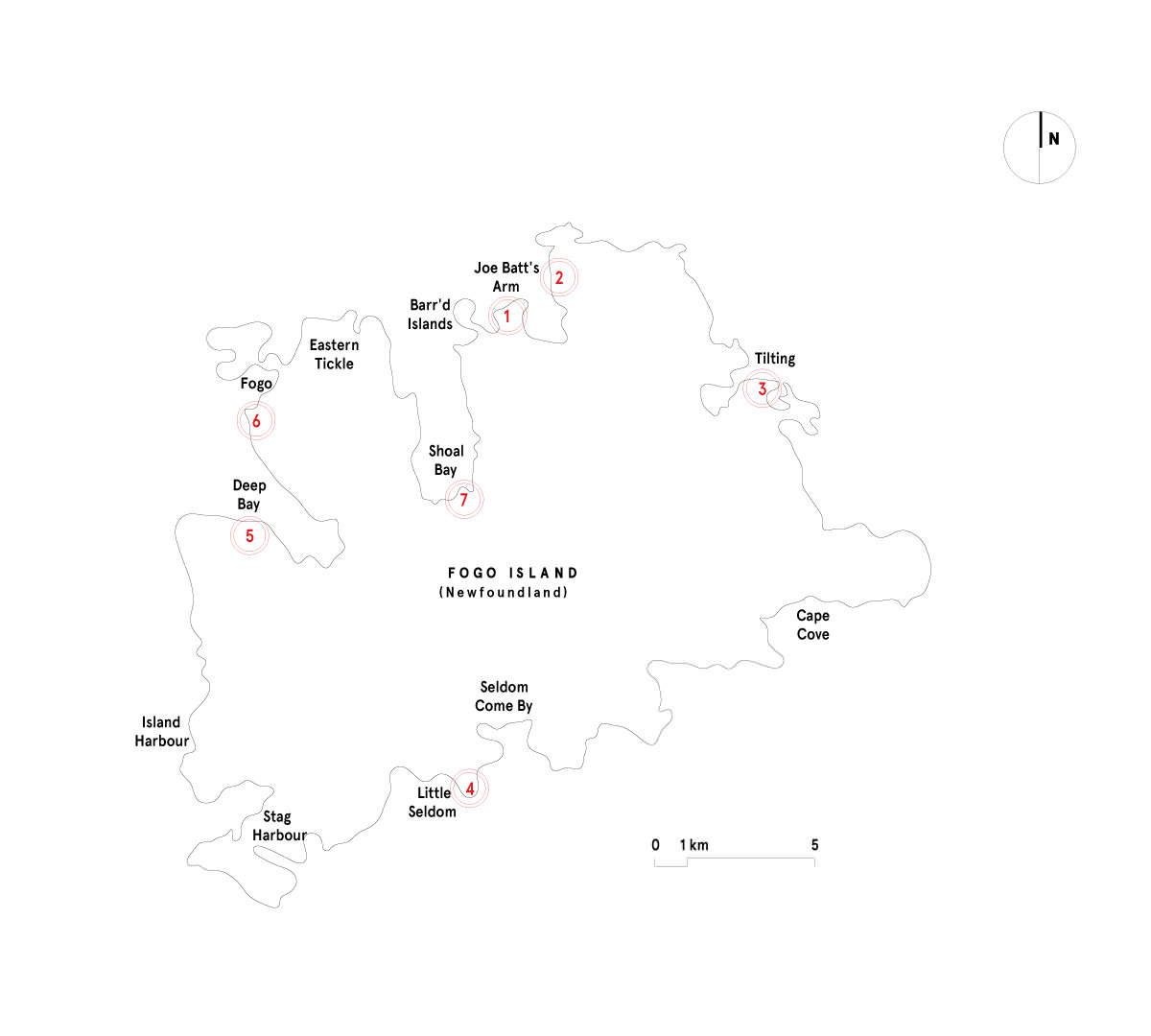

Map of Fogo Island, Newfoundland, showing the relative positions of the six artists studios and the Fogo Island Inn, which are being built by the Shorefast Foundation to provide residencies and a sustainable focus for culture and employment on the island. Of these, four studios have already been completed and the Fogo Island Inn is under construction. Two studios: Short Studio and Fogo Studio, shown feint in the key, are not yet built.

1 FOGO ISLAND INN

2 LONG STUDIO

3 SQUISH STUDIO

4 SHORT STUDIO

5 BRIDGE STUDIO

6 FOGO STUDIO

7 TOWER STUDIO

-

![]() Fogo Island Inn under construction.

Fogo Island Inn under construction. -

What I like is the sense of humor in your structure: how the handrails curve down like in a swimming pool – yet here it’s over a vertiginous drop. It’s almost surreal.

Tommy and I are both afraid of heights – so there is the quirkiness of the glass barrier at the end which is not vertical but it’s tipped outwards. When you come to it you have to trust it. Lots of people don’t go out that far! Maybe you’re right: I suppose there is a bit of humor in it.

And then more recently another “off-place” project came along: Fogo Island. How did that project come about?

Well the client, Zita Cobb, established the Shorefast Foundation as she had this idea to invest in culture on the island, which is off Newfoundland

»It sounded like a

dream project from

when you’re at

architecture school!«where she grew up. It’s quite remote as its economy was based on the fishing industry but there’s none there anymore. Everyone is leaving, especially the young ones, and she wanted to inject something into the mix to keep the island alive.

She could have made a clothing factory. But she had this idea that money disappears while culture does not. So she came up with plans for an art foundation instead, offering residencies on the island. She wanted to find a local architect for the project when she read an article about me in a Canadian newspaper – I grew up in Newfoundland – and she called me, actually whilst I was paddling my kayak! It sounded like a dream project from when you’re at architecture school!

It’s a series of six artists’ and writers’ studios, -

A perfect kind of bleak: Long Studio, Fogo Island, 2010

-

![]()

all sitting directly in the landscape, with a linked hotel, the Fogo Island Inn. The island is pretty much the same sort of place that I grew up in, so I didn’t have to do research. A lot of it was intuitive: the smell, the wind, the weather, I knew everything about it. There was no guesswork.

How did you choose the sites?

Good question. The Canadian government owns most of the property near the ocean on the Island. The aim was to find a variety of different situations and environments. We originally suggested about ten possible sites, and discussed it with the people living in the towns, adding their further suggestions.

Do you have a favorite site?

I think the writer’s studio – the Bridge Studio, like a box – is my favorite. I called it the ugly cousin after we designed it. We wondered if it was too simplistic. But I like it.

The constant drama of light and landscape from morning to evening: Squish Studio, Fogo Island, 2011.

![]()

»A lot of it was

intuitive: the smell,

the wind, the weather,

I knew everything

about it.« -

![]()

![]()

The Bridge Studio: from the bridge to the entrance, to the white yet cosy, timber-lined interior. Nick-named “the ugly cousin” by Todd Saunders for its uncompromisingly simple box-like shape, it is his favorite of the six studios.

-

The next stage of the project is the hotel: the Fogo Island Inn, which is more for regular people coming to the island, and presumably for local employment?

It’s more a business than the artists’ studios. But the way we’ve tried to do it is that there is almost no divide between the studios and the Inn. So there is an art gallery at the Inn, a nice library and a small digital film-house – basing the interior on old film-houses in New York to get that atmosphere.

So the Inn is almost like a mini art-center, as well as a hotel?

That’s a good way of describing it. We are trying to do more a kind of anti-hotel.

From afar the forms of all the Fogo Island projects look very contemporary.

Yes, but they are very rooted in the place.

![]() The Tower Studio is positioned out on a long peninsula, so as people walk or drive by, they see it from all directions, gently twisting far off.

The Tower Studio is positioned out on a long peninsula, so as people walk or drive by, they see it from all directions, gently twisting far off. -

![]()

![]()

![]()

Up, down, and all around. The interior of the Tower Studio

»I didn’t want the artist to be like a dancing

bear living out in the studio. They can then be

in the community and get to know people.« -

»It has a different personality

depending on your viewpoint

and is not just a static object in

the landscape.«Tower Studio, Fogo Island, 2011

-

Todd Saunders founded Saunders Architecture in 1998. Saunders was born in Canada and has lived and worked in Bergen since 1996, following his studies at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design in Halifax and McGill University in Montreal. He combines teaching with practice as he teaches part-time at Bergen Architecture School. He has also lectured and taught at schools in Scandinavia, the UK and Canada and was visiting professor at the University of Quebec in Montreal.

All the material and construction is traditional to Fogo Island or at least Newfoundland. So I like this expression “strangely familiar:” when one of my uncles saw one building, he said “that’s a little different.” But when he got up close, everything was familiar to him in the construction.

In some of the studios you can spend the night, but in general each artist actually lives in an old house in the town. These old traditional houses are so simple and, to my mind, so beautiful. I didn’t want the artist to be like a dancing bear living out in the studio. They can then be in the community and get to know people.

What is your process of design? How do you conceptualize your work?

We work with a lot of physical models at first – but rather than form following function, we fit the form to the landscape.

»Out in the landscape,

you really appreciate

things. You shouldn’t

actually build there. You

can’t really improve it.«So if you take the Tower Studio, for instance, it’s out on a long peninsula, so people see it from all directions. If you’re walking or driving by, you see it gently twisting far off. It has a different personality depending on your viewpoint and is not just a static object in the landscape.

So in general where does your connection with landscape come from?

I grew up with hippy parents and we spent our summers in a little house in the middle of nowhere with no electricity and no plumbing, and that was one of the best times of my life!

Maybe that was formative in why I respect beautiful places so much. Out in the landscape, you really appreciate things. You shouldn’t actually build there. You can’t really improve it. You know you get a commission in one of these places and just hope that you do not screw it up afterwards!![]()

-

Spanish Colors

Selb, a small and shrinking German town, at a remote spot on the Czech border, is not the most obvious place for young Spanish architects to start their career. But for the team of tallerde2 & Gutiérrez de la Fuente from Madrid, it was the perfect place. They won the Europan competition in 2006, to regenerate the inner city of Selb, and now a few years later have completed their first building there: a colorful day-care center that was recently awarded the international prize of the German architecture magazine Bauwelt. It is a building that is testament to an extraordinary project, coordinated over 2,000 kilometres between site and office.

![]()

Video produced by Bauwelt TV

![]()

Photo: Fernando Alda, Sevilla

-

REVELATIONS

OF ATELIER

LE BALTOCultivating beauty

in the off-spacesText by Jessica Bridger

-

![]()

atelier le balto is Marc Vatinel, Véronique Faucheur, and Marc Pouzol, a trio of French born, Germany and France based landscape architects. Their projects center on the use and reuse of urban conditions, atmospheres, and spaces. (All images courtesy atelier le balto)

-

We show people places they know but do not see.« So begins Véronique Faucheur, explaining the unique working process of atelier le balto. The Berlin-based landscape architecture firm uses the off spaces of the city – vacant lots, forgotten courtyards, parking lots – and imbues them with a certain self-awareness, radically turning a space into a place.

Of course, there is an element of secret discovery about many of atelier le balto’s projects, a certain poetry in the bringing to the surface what was previously obscured – the finding of spaces that seem somehow off the usual map we inhabit in the city.

On hot summer evenings one can nestle against the sheltering walls of the contemporary art museum, Hamburger Bahnhof, reclining on the wooden deck of the Tafel Garten. It is part of Wo ist der Garten? (Where is the Garden?),![]()

Their projects embrace found conditions in urban spaces, many of them in Berlin. The Lichtgarten in Berlin-Köpenick engages the local population with small interventions and vibrant wild plants.

-

»We show people

places they know

but do not see.«Licht Garten, Berlin-Köpenick

-

![]()

a series of projects in Berlin’s Mitte district that took some of these spaces and using minimal intervention transformed them. This is truly an off-place, tucked into a recess in the building’s exterior walls. It was an early find by both Faucheur and Marc Pouzol, two of the three members of atelier le balto – but not together. At the start of Wo ist der Garten? project, one mentioned this space to the other, only to realize that they had simultaneously but separately discovered this secret space, which has now changed from an anonymous niche into a place perfect for a picnic. The emergent vegetation was left, trained into a focus of wild riotous leaves and the occasional fleeting flower. A chalkboard at the very back of Tafel Garten, under the trees surrounded by three walls, became a place for private messages, lone confessions, love doodles.

![]()

![]()

From winter to summer the Schatten Garten, also in Köpenick, creates a space for residents and visitors to walk in a shady urban glen-like place.

-

Wandering Berlin since 1993, Faucheur and Pouzol have since been joined by Marc Vatinel, based in Le Havre (France) to make the core team of atelier le balto. The influence of post-reunification Berlin’s unique urban form is unmistakable in their work. The city was full of open spaces, colonized by plants, devoid of the developer fever, which now flushes these parts of the city from the map. Slowly the wanderings began further afield, the projects more removed from the core. In Faucheur’s words: “It is sad now, to see the open spaces that are left, obscured by fences and boarded up – perhaps it is because of a fear of lawsuits, but these used to be places to discover, to walk into and find new wild places in the city.”

Their work, so influenced by the intangible, is a product of a dialog between drawings, the ineffable qualities of the place, writing, and communal input.The budgetary limitations may have eased somewhat, yet still friends and volunteers, set out additional plants, construct simple structures, carry out a share of the work and – these being gardens – conduct ongoing maintenance. In projects stretching from their Jardin Sauvage at Paris’ Palais de Tokyo to Quebec’s Jardins de Métis landscape exposition and back home in Berlin, atelier le balto’s landscape architecture is crafted with love and respect for the materials and modes of our natural world. There is no division between nature and culture in their work – only the appreciation of the qualities of a place, regardless of its genesis.

In many ways their work is about discovery, uncovering and creating, but it is also about an awareness of impermanence, of the risk of creating in the built environment. After all, it is so much easier to rip out a garden then to tear down a house. Yet at the same»... atelier le balto’s landscape architecture is crafted with love and respect for the materials and modes of our natural world.«

-

time the whims of a formal client can ruin something much faster than a self-initiated action. These are not fly-by-night projects – designed, completed, forgotten – the work is held in the same respect as that for an old friend.

As Marc Vatinel often quotes, André Le Nôtre said, “To know how to guide nature you must respect it,” and this includes the weedy lot, the back alley ailanthus sprouting in cracked asphalt – the work is not a denial of our peculiar green urbanities, but a celebration of the unique atmosphere of rich and layered urban spaces.

Outside of Berlin’s urban core, in Köpenick, there is a pair of projects by atelier le balto, Licht Garten (Light Garden) and Schatten Garten (Shadow Garden), created for the spaces and characters of their names. The counterpointed strategy matches another![]()

The Tafel Garten, in Berlin Mitte, is hidden in back of the contemporary art museum Hamburger Bahnhof. Existing trees and plants are a backdrop for simple interventions such as a wooden deck, perfect for summer picnics.

-

Tafel Garten, Berlin

-

Founded in Berlin by Laurent Dugua (architect) and Marc Pouzol, atelier le balto consists now of Marc Pouzol and Marc Vatinel, both landscape architects as well as gardeners, and Véronique Faucheur, trained as an urban designer. Since 2000, atelier le balto has created many gardens for cultural and artistic institutions in Berlin, Paris, Madrid and Florence.

of atelier le balto’s guiding principles: just like the city itself, these gardens are places to meet people, to interact socially. But at the same time they are spaces to be alone, to look at the natural world, to watch time pass.

In a clear and poignant representation of tracking the life and duration of their projects, atelier le balto have an ever-changing drawing, called “archipelagos”, which maps their projects from east to west in the world, representing them as emergent or on the decline. The office prizes the projects where their involvement stretches over the seasons, over the years. The wax and wane is also reflected in a careful consideration of seasonality. The long shadows of winter give way to the long days of summer. And in the best cases, the projects of atelier le balto endure.![]()

![]()

The chalkboard at Tafel Garten allows visitors to ever-so-briefly leave their mark on the space, bringing the themes of change, impermanence and human fascination into focus in a changing whirl of self-expression. This is the essence of the inclusive yet carefully guided work of atelier le balto.

»The work of atelier le balto

is not a denial of our peculiar green

urbanities, but a celebration of the

unique atmosphere of rich and

layered urban spaces.« -

![]()

Secretly Public in

125 Broad Park Plaza: a rather desolate POP with a waterfront view at 125 Broad Park Plaza. (Image courtesy APOPS@MAS);

Zucotti Park, home of Occupy Wall Street, was one POP widely covered by the press – helping to raise public awareness. (Image courtesy nyclovesnyc.com);

805 Third Avenue: do you want to go chill in this public space? (Image courtesy APOPS@MAS)

-

If it sounds oxymoronic, it’s because it is: a “privately-owned public space” (POPS) is an area within a private building that’s technically open to anyone – that is, anyone who can find it. Established in the 1960s by the New York City government, POPS earned property owners bonuses like extra floor space not otherwise allowed by zoning restrictions. These bizarre urban nether-regions have come under criticism; many of the 525 POPS are inaccessible, uninviting, or downright unusable. However, recent initiatives have been crowd-sourcing public knowledge to map and document them, in an effort to yank city-space back into public hands. Next time you’re in NYC, maybe this interactive map by APOPS@MAS can help you find a strange, secluded place away from it all – and close to you.

![]() (ew)

(ew)![]()

POPS can make you rich: For including a through-block arcade, the owners of 55 East 52nd Street earned 78,000 extra square feet of office space – which earned them an extra 76 million dollars. (Exterior view: Fisherbrothers.com, interior view of the lovely arcade: htsuchiya/Flickr)

![]()

-

Hidden Hotel

One Hotel, located in Kabul, Afghanistan was the stuff of legend until the artist Mario Garcia Torres made the film “Tea” for last year’s Documenta in Kassel (Germany). Rendered off the map by time and transition, the hotel opened in 1971 and was owned and operated by the Italian artist Alighiero Boetti and a friend, Gholam Dastaghir, for six years. This “off place” was Boetti’s sanctuary and a kind of absolution. Decades after its closure, and long since a lapse into obscurity Garcia Torres made a film about finding: the hotel, artistic process, even certain truths. The film reconstructs layers of the past, overlaid like detritus on the façade and structure of the One Hotel, through narration, photographs, and video footage of the search.

![]() (jb)

(jb)Video: “Tea” Trailer directed by Mario García Torres, 2012. Image: Unknown photographer, One Hotel, Kabul, 1971

![]()

-

The Mystery

Train Station

of CanfrancMarc Chagall, Nazi Gold and Doctor Zhivago! It all comes together at a train station that is as grand as forgotten.

Text by Myrta Köhler

The “Blue Staircase” of Canfranc. Photo: Stefan Gregor, 1998

-

In the presence of King Alfonso XIII of Spain, the central train station of Canfranc was inaugurated on July 18, 1928 amid general rejoicing. Progress had finally reached the languid Pyrenees. A symbol of economic upswing, the station on the border between France and Spain was to connect the Iberian Peninsula with the rest of Europe. But after a brief period of splendor, the stone giant fell to ruin. The building that was long ago called the “Titanic of the Pyrenees,” is now finally going to be resurrected.

In the Valle del Aragón you can practically hear the grass grow. It flourishes between the railroad ties, obscuring the rails. The sight of an enormous train station building looms above them: a monument from another world, as imposing as the nearby mountains, and perhaps even more quiet and enchanting than the valley. Forlorn train cars covered in graffiti rest atop deserted train tracks. The windows of the main building are shattered, the doors locked. No trespassing.![]()

The huge and derelict train station of Canfranc, also called the “Titanic of the Pyrenees” is located almost on the border between France and Spain. (Photo: Matthias Maas)

-

»From Canfranc, the train drove straight into freedom!«

Photo: Matthias Maas

Photo: Matthias Maas

-

![]() Photo: Stefan Gregor

Photo: Stefan Gregor -

![]() No trains today. (Photo: Stefan Gregor)

No trains today. (Photo: Stefan Gregor)![]() The glory has departed: (Photo: Stefan Gregor)

The glory has departed: (Photo: Stefan Gregor)And yet they come: tourists, weekenders – and photographers. Where there is a will, there is also a way inside the building. Matthias Maas, a photographer from Würzburg, describes his first visit in 1996: “It was dark, cold and rainy – a real graveyard atmosphere. Terribly uninviting.” Inside it was clammy and damp, pervaded by the smell of mold. But he forced himself to unpack the camera – and was instantly spellbound. Together with his partner, Stefan Gregor, he would return regularly to document the giant’s demise.

The contrast between the majestic building and the sleepy municipality of Canfranc is staggering. Only a handful of people live here – far too few for a train station of such magnitude. The three-story central building is an eclectic construction nearly 250 meters in length. It holds not only the cavernous ticketing hall embellished with stuccoed ornamentation, but also an infirmary, a customs office, and a grand hotel. And all for what? -

In the mid-nineteenth century, at the pinnacle of the Industrial Revolution, the route from Zaragoza (Spain) to Canfranc to Pau (France) was to be the shortest possible route linking the centers of northern Spain with those in southern France It was not until 1915 that rivers were diverted, railway embankments backfilled, and the 7.8 kilometer-long Somport tunnel was plowed through the Pyrenees Mountains. The excavated granite provided the foundation for the Canfranc station, realized by architect Fernando Ramírez de Dampierre. As an international hub, it would herald the arrival of modernity in the Pyrenees and transport the glory of a small region far beyond its own borders.

But a major opportunity was missed: Spain refused to exchange its broad-gage railways for the standard-gage rails used in the rest of Europe, because of the possibility it would encourage an invasion by France. Therefore, goods as well as people had to change trains in Canfranc. An operational delay was unavoidable. There were long travel times due to the extreme inclines and narrow curves. The line also suffered considerable financial loss because of politically induced stoppages: from 1936 to 1939, because of the Spanish Civil War, and then again from 1945 to 1948. On top of this, the route was never used to capacity and was thus destined for eventual economic failure.

»The train station is a European symbol that never really had a chance to live.«

-

![]()

![]()

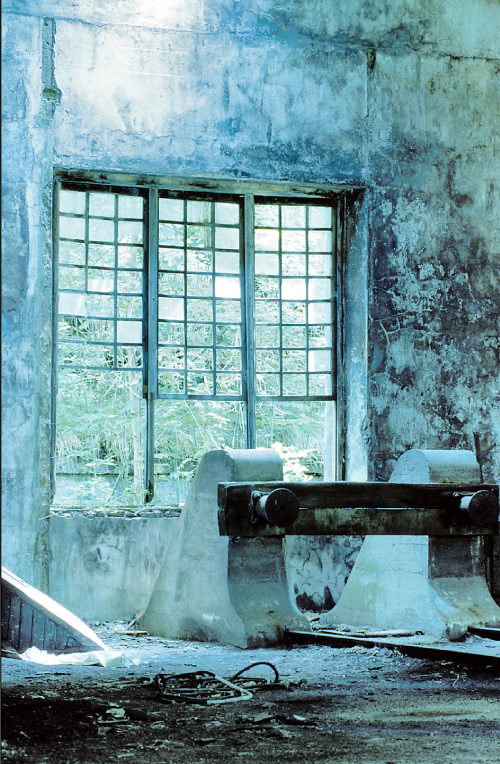

In the train shed. Photos: Stefan Gregor, 1998

-

The Hub of History – and its Decline

Still, Canfranc did experience a rather macabre heyday during World War II. The Third Reich exported 86.6 tons of gold via Canfranc to Spain and Portugal – this included “Nazi gold” – tooth fillings and jewellery stolen from murdered Jews. In return, Germany received what it urgently needed for its arms industry: tungsten.

It was not only the Nazis who flocked to Canfranc during the war, but also the secret services of various nations and refugees. In 1940, artist Max Ernst escaped to the USA along this route. Marc Chagall settled here for a time as well. But why choose such a strenuous path through the mountains? Ramón J. Campo, editor of the Spanish newspaper Heraldo de Aragón, explains: “Canfranc was not occupied by the Germans until November 1942 – they took Irún on the coast much earlier,” he writes. “From Canfranc, the train drove straight into freedom!” This not only applied to those fleeing the Hitler regime; ironically, after the war, German soldiers escaped from the Allies through the Somport Tunnel.

Having seen such turbulent times, Canfranc should have received plenty of opportunities to recover. After the war, however, the train station was only a ghost of its former self. As the backdrop for the film Doctor Zhivago, the Canfranc colossus again made headlines – but then came its coup de grâce. In 1970 on the French side, a freight train derailed, causing the collapse of the bridge at l’Estanguet. This brought an end to the international rail connection. A bus line was established between Oloron Sainte Marie and Canfranc for passenger transport; today, cargo from France is delivered by truck and then loaded onto trains at Canfranc. On the Spanish side, a regional train attached to a single locomotive passes twice daily – it stops at a provisional platform near the street. The old train station towers behind have fallen into disuse. -

»Evidently the place was also frequented by dealers and junkies – they noted on the walls where to find the best drugs.«

The hotel’s foyer. (Photo: Stefan Gregor, 1998)

-

Then again, perhaps the station was not entirely unoccupied. Matthias Maas relates how people were “living” under the roof, well into the nineties: “Sometimes I heard steps above me, but I never saw a face. From the side of the unused French tracks you could sometimes see laundry hanging out to dry.” Stefan Gregor added, “An interpreter translated some of the graffiti for us. Evidently the place was also frequented by dealers and junkies – they noted on the walls where to find the best drugs. Many of them also slept here – there were mattresses lying around, with piles of excrement in between ... not a comfortable place to be!”

Indeed, there is little left of the comfort of the formerly grand station hotel: the paint on the doors has peeled, the locks rusted. The stucco along the stairs has fallen off, the banisters collapsed. “In winter there were icicles hanging in the stairwell,” said Maas.![]()

![]()

above: The former customs facilities.

right: The old ticket counter in the main entrance hall.

(Photos: Stefan Gregor, 1997/1998) -

“When the temperature rose, the melted water flowed unobstructed through every floor of the building. It will be ruined by the water.” The rest of the structure fell victim to vandalism. In 2007 the train station’s periphery was closed off with barbed wire.

Train Station of the Future

For a number of years now, citizen action groups and non-profits have called for the reopening of the international junction. The greatest amount of trans-Pyrenean transport occurs by road, which is causing extreme environmental pollution due to increasing and heavy traffic. Shifting some of this to the railway could relieve the situation – and would also result in fewer traffic accidents. With today’s technology, any train-related obstacles could be remedied with relatively ease, argues Suter.

![]() Photo: Stefan Gregor

Photo: Stefan Gregor -

![]() Photo: Matthias Maas

Photo: Matthias MaasNumerous upgrades and renovations would have to be made to realize this goal however, including a change on the Spanish to normal-gage rails and electrification on both sides at sufficient voltage, which is more of a hindrance than anything else for contemporary international railway traffic.

If the international route were reopened, a new, smaller train station would be erected at a different location, according to Canfranc’s mayor Fernando Sanchez Morales. The large train station has already served its duty as such; current plans include its transformation into a five-star hotel. But here, too, the continuing economic crisis has left its mark: so far, only the roof has been repaired.

For the time being the giant stands, peaceful and patient. Tourists continue to visit. Busses depart from here to the winter sports destinations Astún and Candanchú. Pilgrims find their way here as well:»The train station should be a meeting place — for people who envision the future.«

-

the Spanish “Way of St. James” to Santiago de Compostela begins in Puerte de Sompor and passes by the train station. In the summer of 2010 Matthias Maas also decided to travel the route – an occasion to visit “his” train station again for the first time in several years: “It was abominable! They sawed gaping holes into the building, removed the original green painted doors and simply nailed some kind of inside doors across the openings in their place.” Additionally, the building was surrounded by concrete slabs to support the scaffolding for the roof renovation. “I think no one really understands what value the building has as a political monument. It was born from what had been a very progressive idea of bringing together two capital cities – at a time when nationalist agendas were the order of the day.” This joining aspect is very important to Maas: “The train station should not become a hotel,” he is convinced. “Here should be a meeting place – for people who envision the future.”

![]()

![]() Photo: Matthias Maas

Photo: Matthias Maas -

In the Photo Booth with ...

Gottfried Böhm

Well, to be frank, this isn’t really a photo booth. When we met Gottfried Böhm on one of those bitterly cold January nights in Berlin, it was well below zero and it would have been too cruel to pull the nonagenarian Pritzker Prize winner into the dark, freezing photo booth across the street. Instead, we slipped into the nearest “off-space” we could find – the tiny storage room of the Aedes gallery (where he was about to open his latest exhibition “Visions”) – to ask him a few questions.

Interview by Florian Heilmeyer, photos by Erik-Jan Ouwerkerk

![]()

-

From a distance it’s a bit difficult to imagine Gottfried Böhm “retired.” Does this really exist for you: retirement?

(Laughs) That’s very nice of you. No, I can’t imagine Gottfried Böhm in retirement either. I’m happy when I have work. Otherwise I meddle in my sons’ affairs: recently I helped my son Peter with a competition.

Herr Böhm, first of all, congratulations! Tonight you are celebrating not only the opening of your most recent exhibition, but also your 93rd birthday.

Yes, thank you.

-

Of your four sons, three are architects. You were clearly successful in demonstrating that leading the life of an architect is something quite desirable.

My father Dominikus was also an architect, as was my grandfather Alois. It seems to run in the family. I’ve always wondered why three of my sons become architects. It’s nice, but I don’t exactly understand why they chose to do it. And while the fourth, Markus, studied computer science and geology, he is now working with buildings as an artist, and has also contributed to several of my projects. So he has also joined the club. Of course he is by nature someone who understands building and the job of an architect very well. So perhaps it’s not so big a jump for him to develop in that direction.

-

In your biography, the Pritzker Prize you were awarded in 1986 has always been given great importance. Was this honor really so important and make a great difference in your professional life? Did you receive more commissions as a result?

The Pritzker Prize was a huge surprise and a great honor. But a major impact? Probably not, I think. Perhaps the Pritzker Prize made me a bit more self-confident. But economically, I don’t think it played such a big role. After all, we had already made a name for ourselves and had our commissions – which we continued to work on.

-

Gottfried Böhm (*1920) is an architect and sculptor, who began his career after World War II in the architectural firm of his father, Dominikus Böhm. Following in his father’s footsteps, he started by building churches, of which he has realized nearly 60 until today. He became famous for his sculptural style, using primarily concrete for his expressionistic forms. Many of his buildings became icons of 20th century architecture, such as his pilgrimage church in Neviges (featured in uncube No. 01) and the city hall in Bensberg. On 23 January 2013 he turned 93, celebrating this with the opening of a new exhibition in Berlin entitled Visions.

Is there anything missing in your expansive life’s work? Is there something that you would still like to have built?

Many of my designs have not been built. That’s always a disappointment. But no, in general, I am quite satisfied with everything I was allowed to build. On the way here today, I stopped in Potsdam and visited the Hans-Otto-Theater. It’s amazing to have built something like that. Of course I still get around every now and then, and when I do, I enjoy looking at the buildings. It’s true what you say: it is an expansive portfolio. I often pass by places where I have built things, and I am glad when the users are still happy with them.

![]()

-

Bauhaus Travel Book. Weimar. Dessau. Berlin

Ed.: Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin, Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau, Klassik Stiftung Weimar

DuMont Publishers, 2012

304 pages, Color, Hardcover, 210 x 160 mm

ISBN 978-3-8321-9412-3

www.dumont-buchverlag.de

If there ever was a perfect book, this might well be it. Surprisingly, this is the very first travel guide to the sites of the historic Bauhaus (1919-1933) in Germany, including in-depth background information, maps and practical travel tips. With a brilliantly clear layout and a handy format, the routes include the well-known Bauhaus sites of Weimar, Dessau, and Berlin, but also the obscure: a small village church in Gelmeroda, for instance, which featured in Lyonel Feininger’s paintings. But what really makes this book an invaluable treasure chest is, that it traces the Bauhaus not only through space, but also through time: with biographies and stories about all the key protagonists following the Bauhaus’ diaspora worldwide. This book makes one want to go on a “grand tour” immediately to see all the sites – but it’s also a great read. (fh)

Bauhaus Travel Book![]()

![]()

-

Manifest Destiny: A Guide to the Essential Indifference of American Suburban Housing

Edited by Jason Griffiths; afterword by Martino Stierli

AA Publications, 2012

144 pages, Color, Hardcover, 220 x 170 mm

ISBN 978-1-907896-05-7

![]()

Manifest destiny: the uniquely-American myth of endless expansion. As Jason Griffiths’s own expansive manual charting the landscape of today’s American suburbs suggests, this urge to settle and domesticate has never really vanished. The continual manifestation of America’s destiny is cataloged here in all its contradictory glory – what Griffiths calls the simultaneous “push from the past” and “pull to the new.” Especially telling are the often absurd photographs snapped by Griffiths and his travel partner, Alex Gino, over their 178-day journey through suburbia, detailing the moments when progress gets ahead of itself (unfinished constructions, empty streets, bizarre or redundant architectural elements). The suburb is contextualized here without judgment but with true curiosity, situating it within its long American tradition; from the log cabin all the way to the pre-fabricated wooden shell of a home at the end of a suburban cul-de-sac. (ew)

Manifest Destiny: A Guide to the Essential

Indifference of American Suburban Housing![]()

-

The Road to Oxiana,

Robert Byron

Introduction by Colin Thubron

Penguin Classics, 2007

368 pages,

Paperback, 129 x 198mm, £9.99

ISBN 9780141442099

www.penguin.co.uk

![]()

This travel book is, in the true spirit of that hackneyed term, a real classic - even 75 years after publication.

An account of the journey Robert Byron took in 1933-34 from Venice via Beirut, Jerusalem, Baghdad and Teheran to Oxiana, the area where Afghanistan met the then Soviet Union. The book was groundbreaking in its day for its diaristic mix of personal incident and anecdote, with descriptions and photographs of the jaw-dropping structures – mosques, shrines, towers (like the 72 meter brick tower Gumbad-i-Kambus built in 1006) – that pepper his route. Byron is only unrestrainedly prejudiced about architecture (loves Islamic; hates Greek and Buddhist: the two great Buddhas at Bamian, destroyed by the Taliban, are “monstrous”) but not about people, who are never stereotyped, even when mercilessly critiqued. (rgw)

![]()

-

![]()

-

Culture & the City

Can culture help a city become something else, something better, something – more precious? 16 years after the so-called “Bilbao effect” we’ll be exploring how cities have tried to reinvent themselves through cultural buildings. It will be a cooperation with the Akademie der Künste in Berlin, where the exhibition »Kultur:Stadt«, curated by Matthias Sauerbruch, opens on March 14th, 2013.

![]()

![]()

Aerial view of the Skid Row neighborhood, with Downtown L.A. in the background and Inner-City Arts, designed by Michael Maltzan and built 1993-2008, in the foreground. (Photo courtesy Michael Maltzan).

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»I hate vacations. If you can build buildings, why sit on the beach?«

Philip Johnson

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents

Corner of Todd Saunder’s office. (Photo courtesy Saunders Architecture)

Corner of Todd Saunder’s office. (Photo courtesy Saunders Architecture)

Photo: Matthias Maas

Photo: Matthias Maas