-

Magazine No. 09

Constructing Images

-

No. 09 - Constructing Images

-

page 02

Constructing Images

-

page 03

Editorial

-

page 04 - 19

Every Image is a Construction

Kersten Geers on ambiguity in images and architecture – and avoiding photorealism

-

page 20

Satisfiction

-

page 21 - 35

Behind the Façade

Ingrid von Kruse captures the personalities of starchitects

-

page 36

Think Like a Teenager

-

page 37

Positive Press

-

page 38 - 52

Modern Ruins

Julia Schulz-Dornburg photographs Spain‘s unfinished buildings

-

page 53 - 56

The Full & The Empty

Economic crisis and the abandoned developments in Spain

-

page 57

Triumph of the Spectacle

-

page 58 - 63

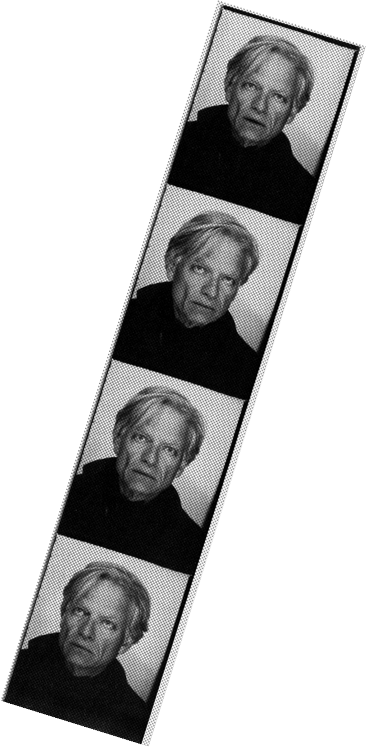

In the Photo Booth with...

Roger Diener

-

page 64 - 66

Bookmarked

-

page 67 - 68

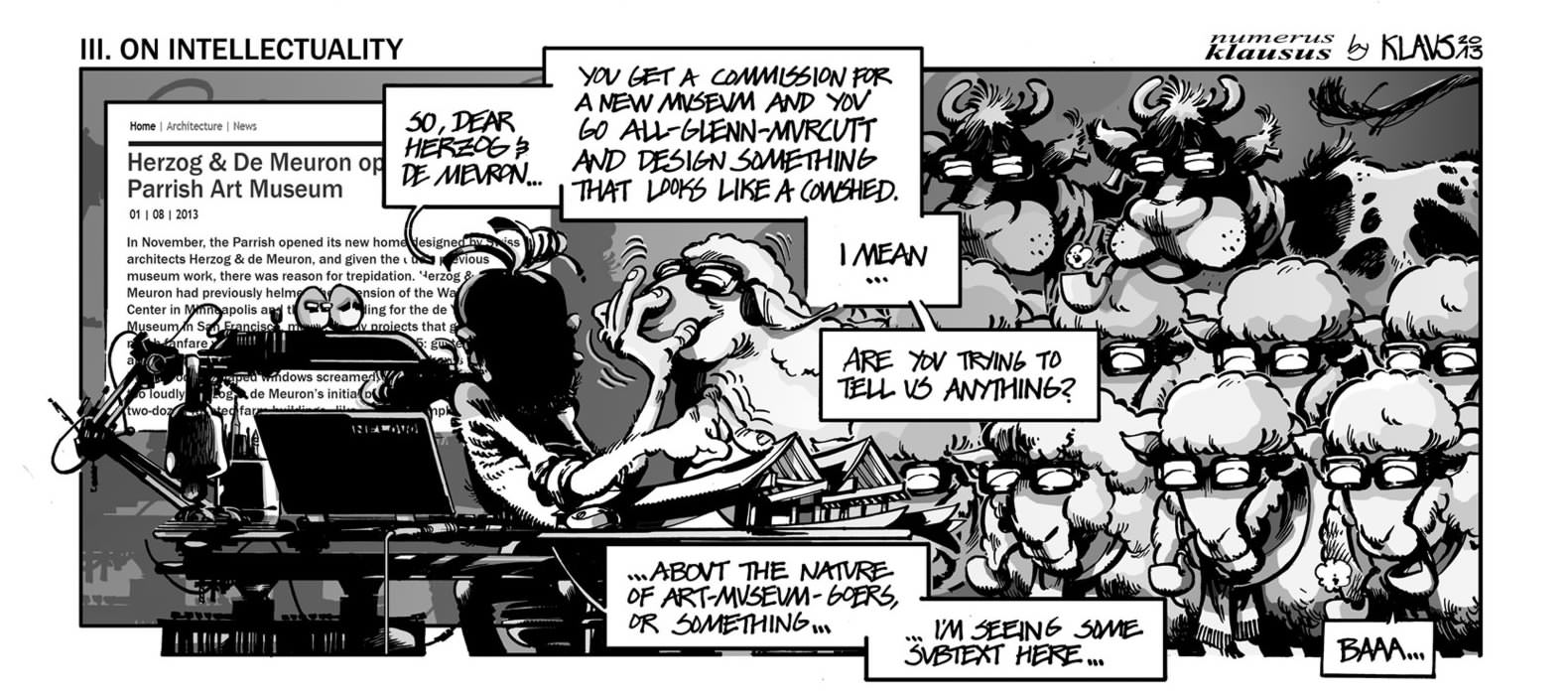

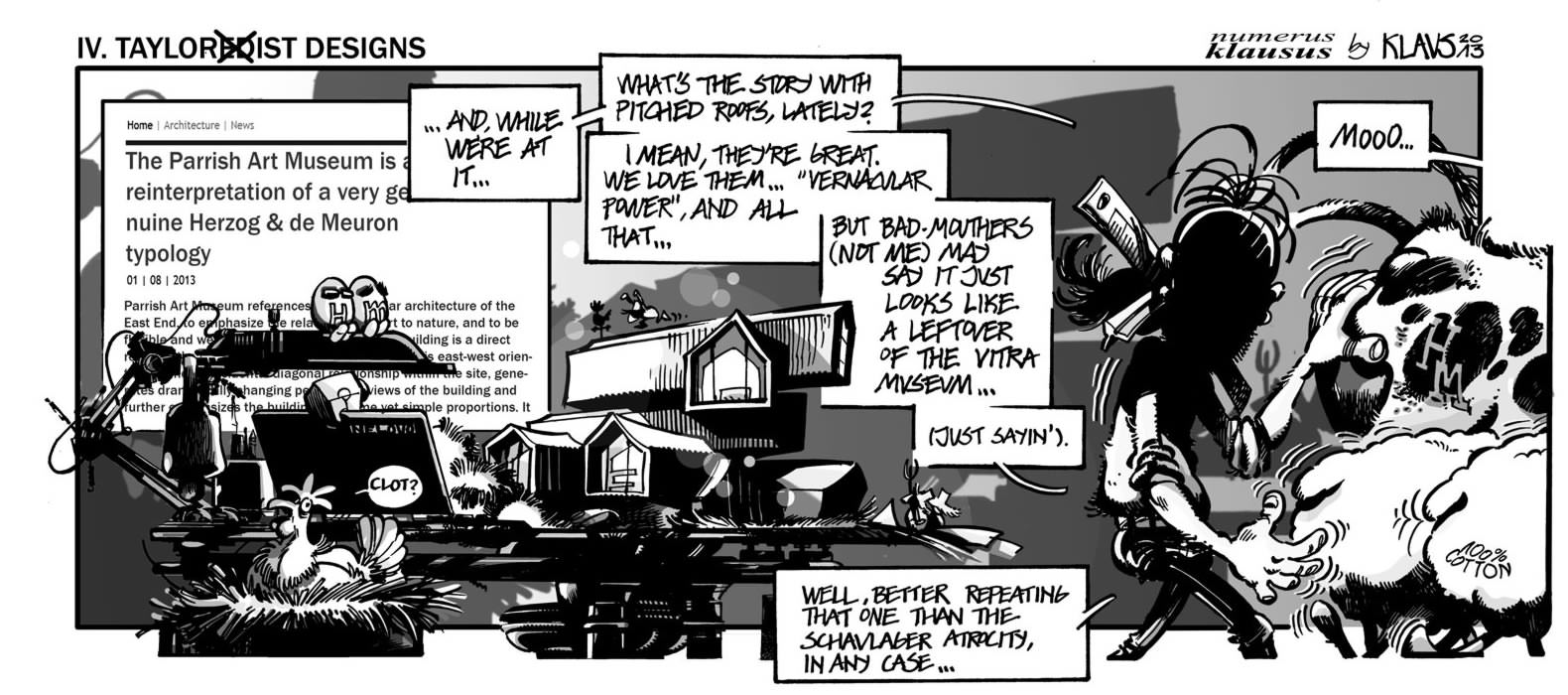

Klaustoon

III. On Intellectuality

-

page 69

Next

Wood, Paper, Pulp

-

page 70 - 71

The Dessau Effect

How the Bauhaus has defined a city’s image since 1926

-

-

As an online magazine, we at uncube fully appreciate the importance – even the dominance – of the image today.

In recent years, architecture has become inextricably tied to the images that represent it. From the pre-construction rendering to the post-production money-shot, endless images of architecture get flushed through a myriad of media outlets every day. Usually we never see, smell, hear, or feel these places ourselves.

In this issue, we’re finding out how 2D images – of buildings, people, places, and even concepts – can communicate or confabulate the multidimensional truth.

Lose a dimension. Welcome to the flatlands.

THE EDITORS

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Cover photo: Bas Princen

-

Every Image is a

ConstructionKersten Geers on ambiguity in images and architecture – and avoiding photorealism

Text by Florian Heilmeyer

-

Founded in 2002, the Belgian architecture office of Kersten Geers and David van Severen, simply called “OFFICE,” has produced architecture that manages to be precise and ambiguous at the same time, modern and full of references to the past – and the images they produce reflect this: they steer clear of any kind of photorealism, doing good old collages instead.

We met Kersten Geers where he works in the heart of Brussels, in a rather ugly little 1970s office building offering a panorama view of the roofs in the old city centre.

![]()

David Van Severen (left) and Kersten Geers (right) at OFFICE in Brussels. (Photo: OFFICE)

-

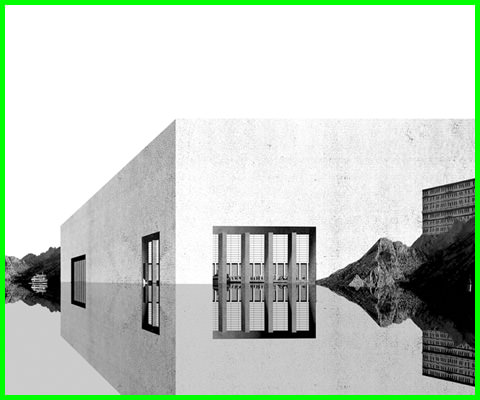

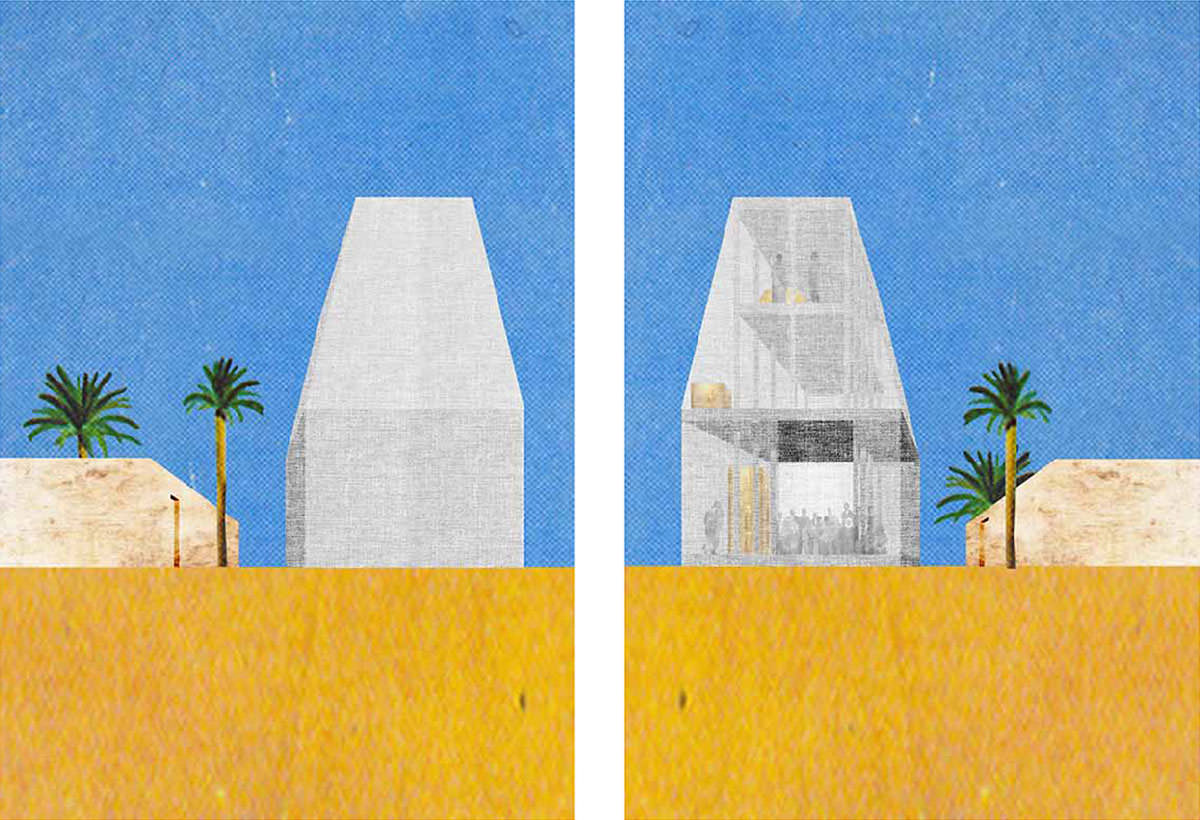

Today, architecture seems to be forced to produce visuals that are as realistic as possible. Kersten, it seems that OFFICE has always refused to produce any imagery like that. Your images are collages with bright colours, very accessible and clear. Yet there is always a play with perspective, with the construction of the image, which makes them spatially slightly confusing, creating an uncertainty in the image: something distorted and disturbing. How did you develop this visual language?

We didn’t develop it. It emerged from our interests and influences – from the things that we like. What interests us is a complex approach to realities. We are interested in a lot of things: the art of John Baldessari, David Hockney, Ed Ruscha; in Aldo Rossi, James Stirling, Reyner Banham.

We are also interested in O.M. Ungers – well, at least in a few things by Ungers! More in his way of thinking: as an architect he was often rather disappointing. Sometimes it is only a very definite period of an artist’s or architect’s work that we find interesting. The young Koolhaas was a genius. The short period when Koolhaas and Kollhoff were working in the office of Ungers must have been an absolutely fantastic time! The sad thing is that Koolhaas’ epigones are not in the least exciting. They lack his radical quality and complexity, they’re only interested in the pictures.

We are interested in early modern Viennese architecture, before it became labeled as such. When, for a short time, people were finding simplified shapes that could produce huge spatial complexity. We’re also interested

»The young Koolhaas was a genius. The short period when Koolhaas and Kollhoff were working in the office of Ungers must have been an absolutely fantastic time!«

-

Interior of a summerhouse extension, Ghent, Belgium, 2004-2007.

(Photo: Bas Princen) -

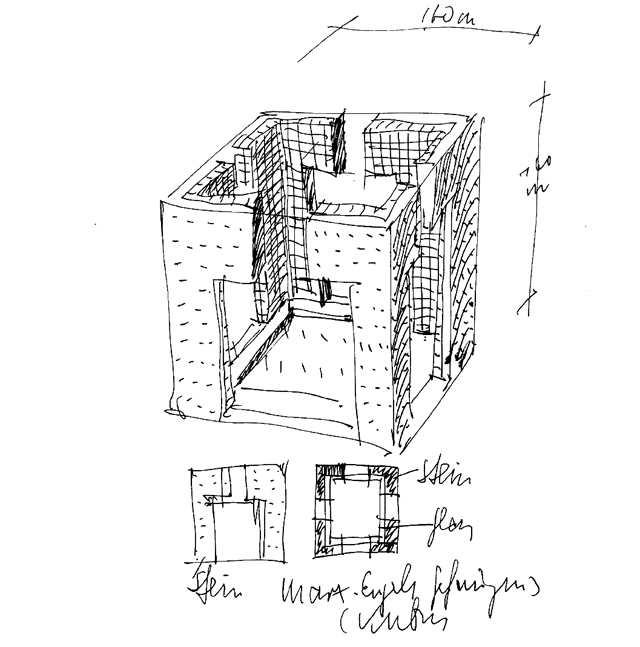

Collage study for Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm University Library International Competition with Dan Budik, Berlin, Germany, 2004.

(Image: OFFICE)![]()

in the Italian Renaissance, in fact, I think it is absurd to be interested in architecture without being interested in the Renaissance. To me, Donatello Bramante was probably the best architect of the past 600 years!

Yet you are certainly neither retro nor nostalgic in your work.

No, we are not. We don’t celebrate what’s been and gone. We use it. Some of the things we like lead to the past, some to the present … and some lead to Los Angeles. For example, Hockney and Banham, both being European, observed the city closely with the eye of a foreigner, studying it in minute detail. It is fascinating the way that Hockney plays with perspectives, which always look rather clumsy and non-spatial, yet produces pictures that are very spatial in a contradictory way, remaining two-dimensional. -

They also have strong references to the early perspectives of the Italian Renaissance, which you mentioned…

Yes. There are quite a few similarities, but the longer you look, there are similarities everywhere. Los Angeles, Europe, Brussels, where we work – they are all melting pots. Maybe we are attracted by this?And naming references is of course always difficult. It seems naïve to mention a big name like Hockney: when we talk to artist friends, of course they raise their eyebrows. But some pictures of his were really, really seminal for David and me. “A Bigger Splash” for example: the water, the wall, the pool, the house, the two palm trees, the fact that there’s nobody there. In some strange way this picture has been very important to us and how we look at images.

Project for Architecture Biennial of Rotterdam, Special Mention Award

Ceuta, Morocco/Spain 2007 (Photo: Bas Princen)

Project for Architecture Biennial of Rotterdam, Special Mention Award

Ceuta, Morocco/Spain 2007.

(Photo above: Bas Princen, Image right: OFFICE)![]()

![]()

-

Computer Shop, Tielt, Belgium, 2008-10

(Photo: Bas Princen)

»We don’t celebrate what’s been and gone. We use it. Some of the things we like lead to the past, some to the present … and some lead to Los Angeles.«

-

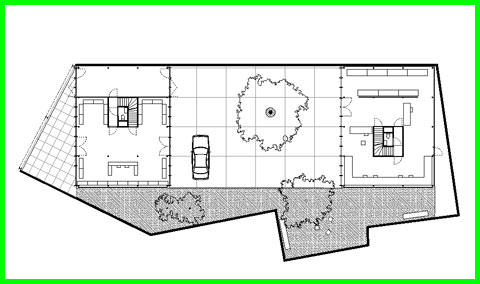

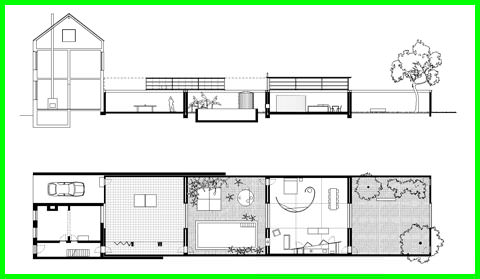

Computer Shop, Tielt, Belgium, 2008-10.

Two identical buildings mirror each other across a courtyard -- one containing the public face of shop and reception area, and the other the logistics and office spaces.(Photo left: Bas Princen, Plan below: OFFICE)

![]()

![]()

-

After the Party. The exterior / courtyard of the Belgium Pavilion for the Venice Biennale of Architecture 2008. (Photo: Bas Princen)

-

When I was in LA, I discovered a few copies of Banham’s “Architecture Of Four Ecologies” with its original cover picture: “A Bigger Splash.” It’s been reprinted many times but unfortunately they haven’t used the Hockney image. I guess it got too expensive.

But it is perfect! It represents the entire content of the book: Hockney and Banham were both Europeans who fell in love with LA. The hedonism, the seriousness, the climate, the light... it's all in this picture. So when I found these copies I immediately bought two – one for me, one for David – because I knew that he would feel the same way.

So you are saying that it was pictures like this that were lingering in your head when David and you started OFFICE back in 2002?

Yes. On top of that, David and I are quite simply unable to produce renderings, let alone something photorealistic. We have never been interested in computers in that way. When we started working together, we had to look for other ways of expressing ourselves. We were also from the beginning working very closely with Bas Princen...

...the Dutch photographer...

He’s a close friend. We share a lot of interests and we’ve always spoken together about architecture, art, building and photography. I think we learned a lot from each other just by looking at pictures and talking about them. It’s a very natural thing if you like the same stuff. We share a lot of aesthetic references, so we somehow also share the same language.

When you were invited by Kazuyo Sejima in 2010 to be part of her main Venice Architecture Biennale exhibition, you worked in an old garden shed, hidden in a small garden at the back of the Arsenale. In its seven very small rooms you showed a few of your collages and of Bas’ pictures, mixing images of fictitious spaces with ones of real spaces. Was this your intention?

You know what? Working on that exhibition was a very important moment for OFFICE because we’d never realized before just how closely we really work with Bas. But when we were putting together our own images and combining them with Bas’, we were surprised how easy it was. It was done very quickly. Suddenly we realized his pictures have had a huge impact on our work over the last years – and vice versa. As I said: we’ve discussed all our projects with him for years now and he’s taken the pictures of all our built work: he’s like a third partner.

-

Villa in Ordos. A collage study of the design for a 1000-square meter residence in the Mongolian desert, part of the Ordos 100 project, selected by Herzog & De Meuron, curated by Ai Weiwei, Inner-Mongolia, China, 2008. (Image: OFFICE)

-

The Weekend House in Merchtem, Belgium (2008-12), echoes David Hockney’s “A Bigger Splash.” An existing small terrace house and its long back-garden were transformed into an enfilade of different spaces -- from guest house to courtyard, to poolhouse and living room, that can all be enclosed as a single house with a sliding glass roof.

(Photo: Bas Princen, Plan and section top right: OFFICE)

![]()

-

We liked the notion that by combining collages and photographs, reality and fiction get jumbled up together. And then we hit on the idea of Bas taking a photo of the building, and then making a collage out of it and exhibiting it. We put it in a room together with another picture of Bas’ that he took in 2008 of the Belgian pavilion we did back then. It was the only room with two “real” pictures and no collage at all. People were standing in front of this picture, a little confused and unsure, asking us: is this a collage or a real photo? We knew that it would confuse visitors – and we are very fond of bizarre moments like that. Every image is a construction. It was a nice additional aspect to our exhibition helping making that small project more and more complex – which is exactly what we like.

![]()

An office building for VOKA, West-Flanders Chamber of Commerce. In collaboration with Bureau Goddeeris Architectenvennootschap and Bureau Bas Smets.

(Photo: Bas Princen)»David and I are quite simply unable to produce renderings, let alone something photorealistic.«

-

![]()

OFFICE + Bas Princen's Garden Pavilion, Venice, 2010

This installation won the Silver Lion Award at the 12th International Architecture BiennaleLeft: Exterior, Above: Interior of Room 1. (Photos: Bas Princen)

-

![]()

Dar al Riffa, Bahrain.

Collages showing a Hockney-esque use of perspective in studies for an urban renewal project in Bahrain. (Images: OFFICE) -

It seems it’s exactly these references that make your images – like your architecture – appear so precise and radically reduced on the one hand yet so rich and ambiguous on the other?

In a way, all our projects are like members of a family: they can be very different like brothers and sisters can be very different, but they’re all related to one another. It often surprises us: we start a new project, try out a few things and are suddenly wild about some completely bizarre aspect – only to find at the end of the day it resembles an older project in some strange way. Not because that was what we intended, but because it came about through the subjects we’re interested in and because the logic of the project demanded it.

That’s the kind of thing that happens to us. I think it’s a good thing. The fact that we are interested in certain topics gives rise to recurring series in our work that have the same roots. But we don’t repeat ourselves – we’d soon be bored.

We are not interested in precision per se, in perfection. The idea of designing a perfect building would be absurd. Perfection is doomed to failure. Otherwise, an entire perfect universe would have to be created. And this would probably be uninteresting.

Do you feel that in your pictures and collages you can be far more radical than in the projects you realize?

No, because I think that we are very good at translating our concepts into reality. We come to terms with the conditions and still remain true to our ideas, even in the details. Of course, the feelings triggered by a real building are completely different from those a collage or picture evoke. It’s a different medium. But the original intention remains the same.

![]()

»The idea of designing a perfect building would be absurd. Perfection is doomed to failure.«

-

F

Satis

C

T

I

O

NThe work of photographer Filip Dujardin plays like the “straight man” in a comedy sketch: the guy who sets up the joke so that someone else can deliver the punchline. Straight-faced yet anticipating the surprise of realising the impossibility of the architecture, Dujardin’s images allow viewers to finish the joke of the illusion he’s created.

Digital collages made from photos of real buildings, these images are part documentary, part fictional exercise. They allow us a view onto a world we can imagine inhabiting, unconstrained by the limitations of reality – a world that through the virality of the internet, the proliferation of the 24-hour news cycle and hop-on-hop-off disaster coverage can seem more overwhelming or ugly by the day. In this context, the escapism of Dujardin′s work is surely the root of its allure and the cause of its viral spread on the internet.

![]()

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Behind the Façade

Ingrid von Kruse on capturing starchitects on film.

Text by Luise Rellensmann

-

![]()

Ingrid von Kruse (Photo: Luise Rellensmann)

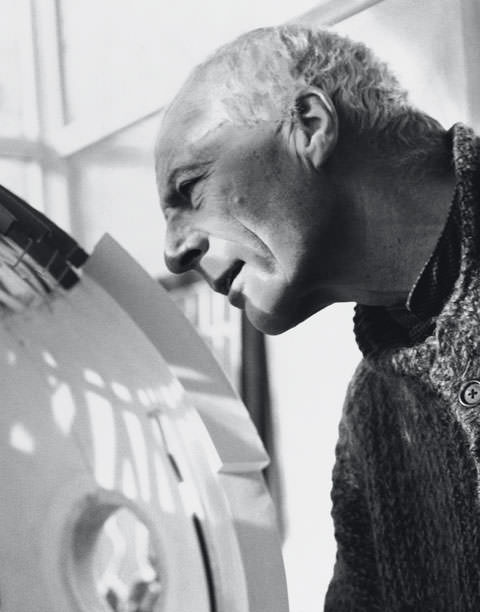

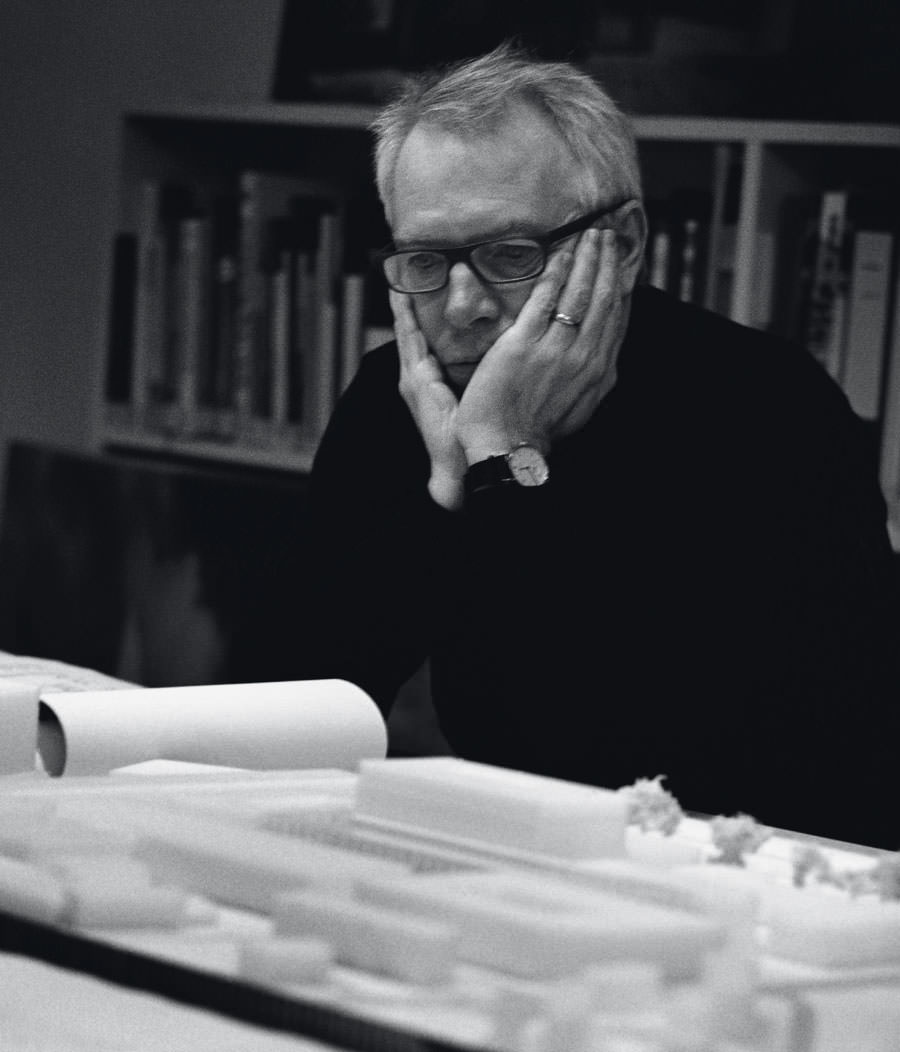

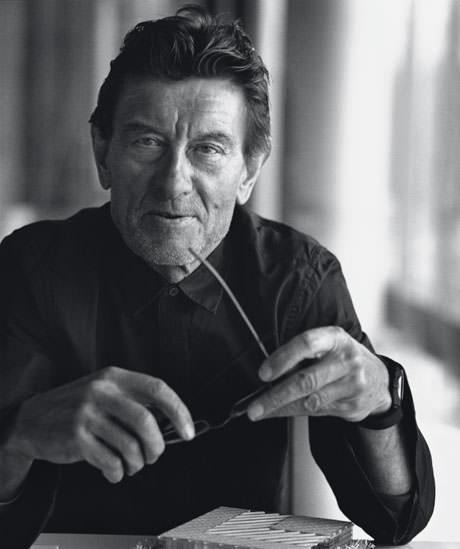

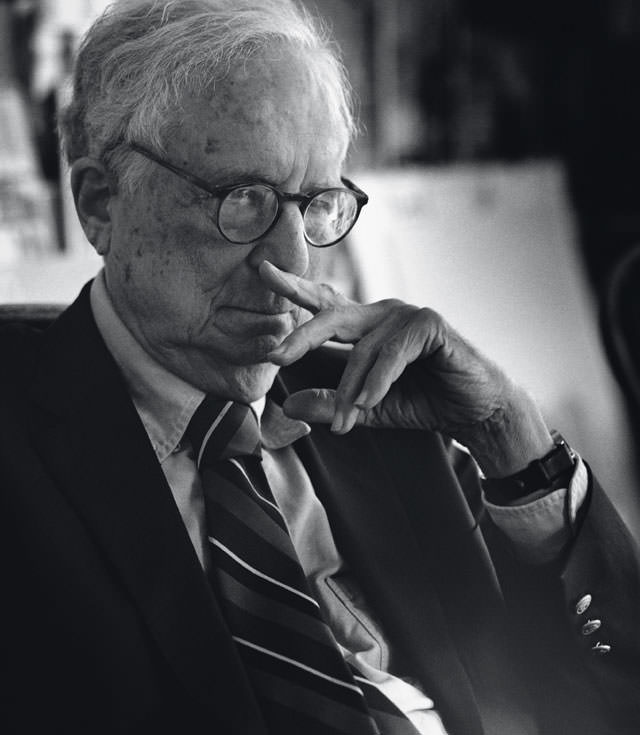

Until a few years ago, the Hamburg photographer Ingrid von Kruse had little to do with architects. The 75-year-old woman had spent her life photographing the intellectual and political elites of Europe – her vast collection of unusually touching black-and-white portraits include Mikhail Gorbachev, Astrid Lindgren, Federico Fellini, Marcel Marceau, Leonard Bernstein, Pina Bausch, and Willy Brandt.

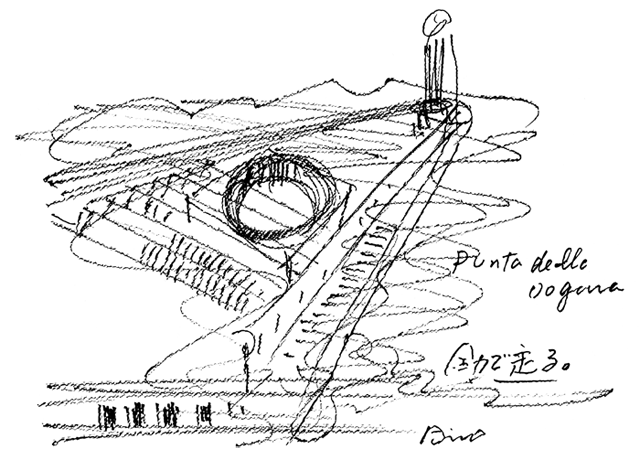

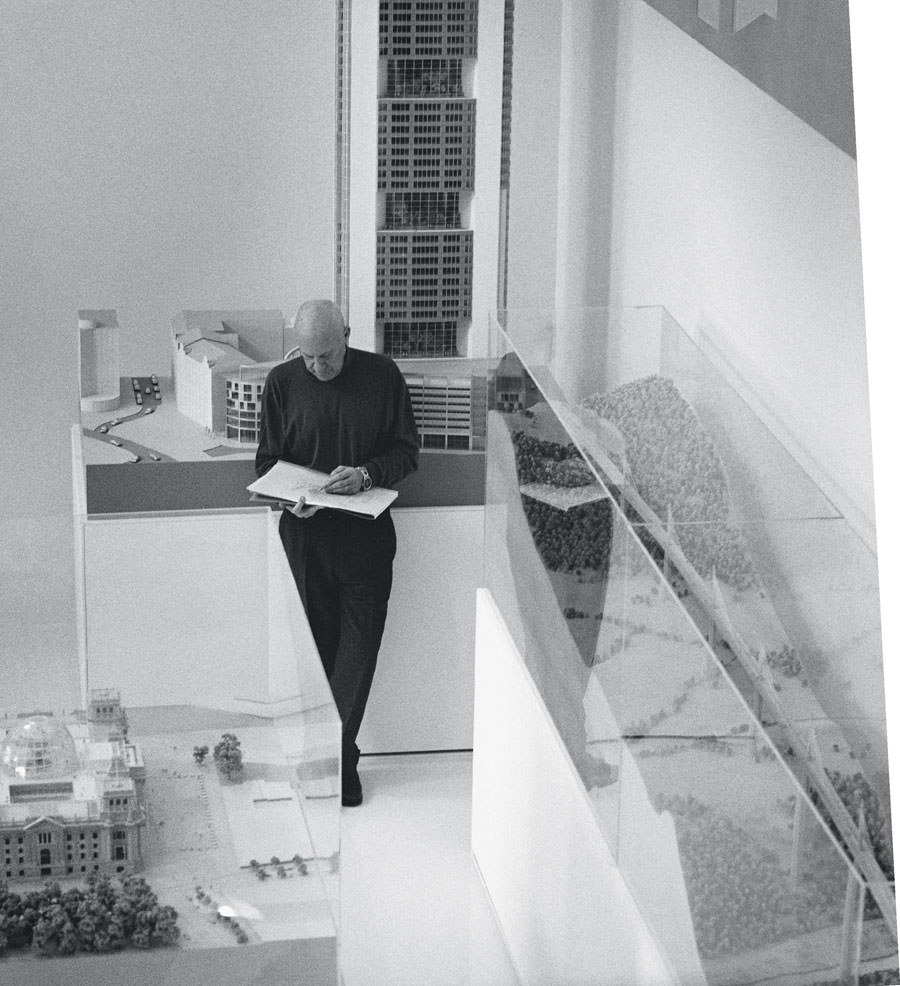

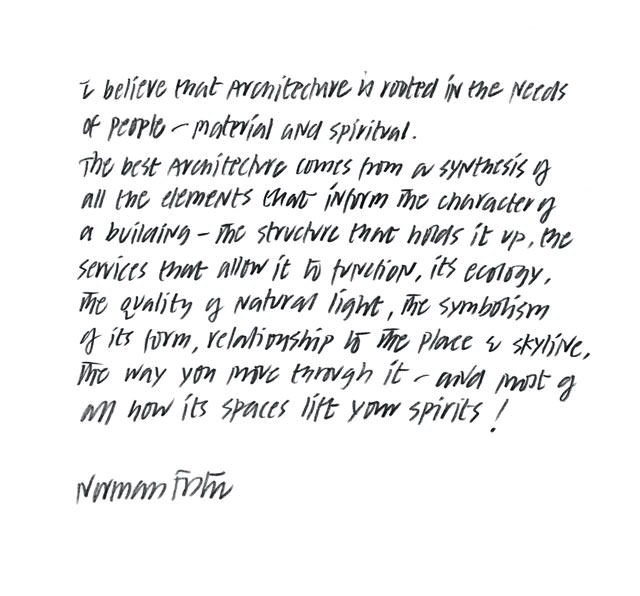

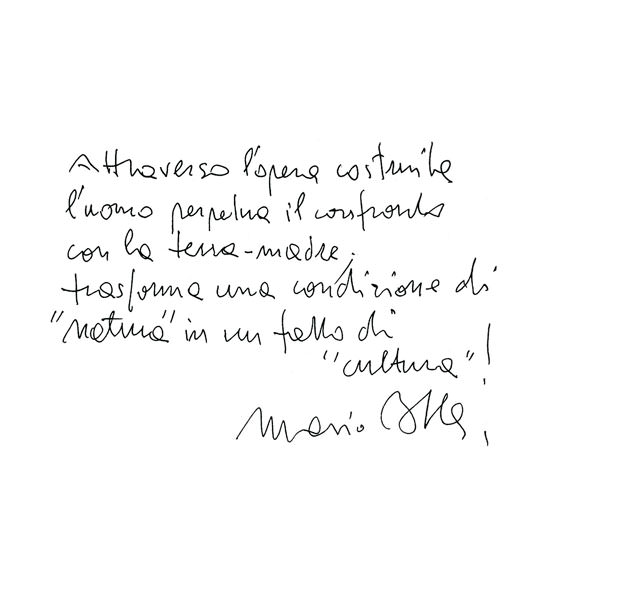

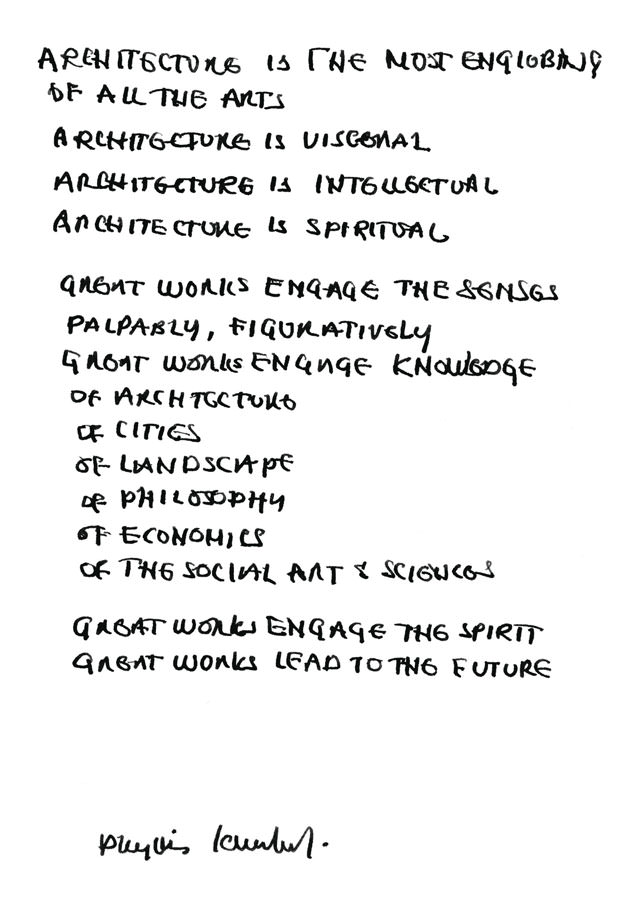

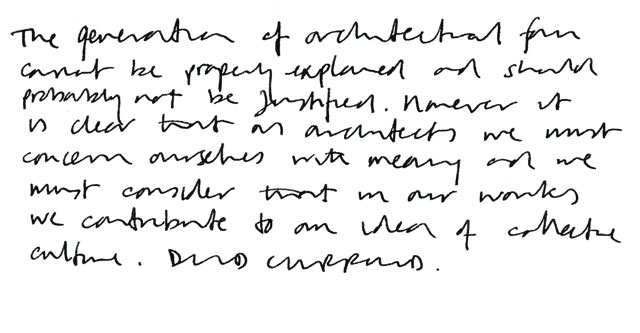

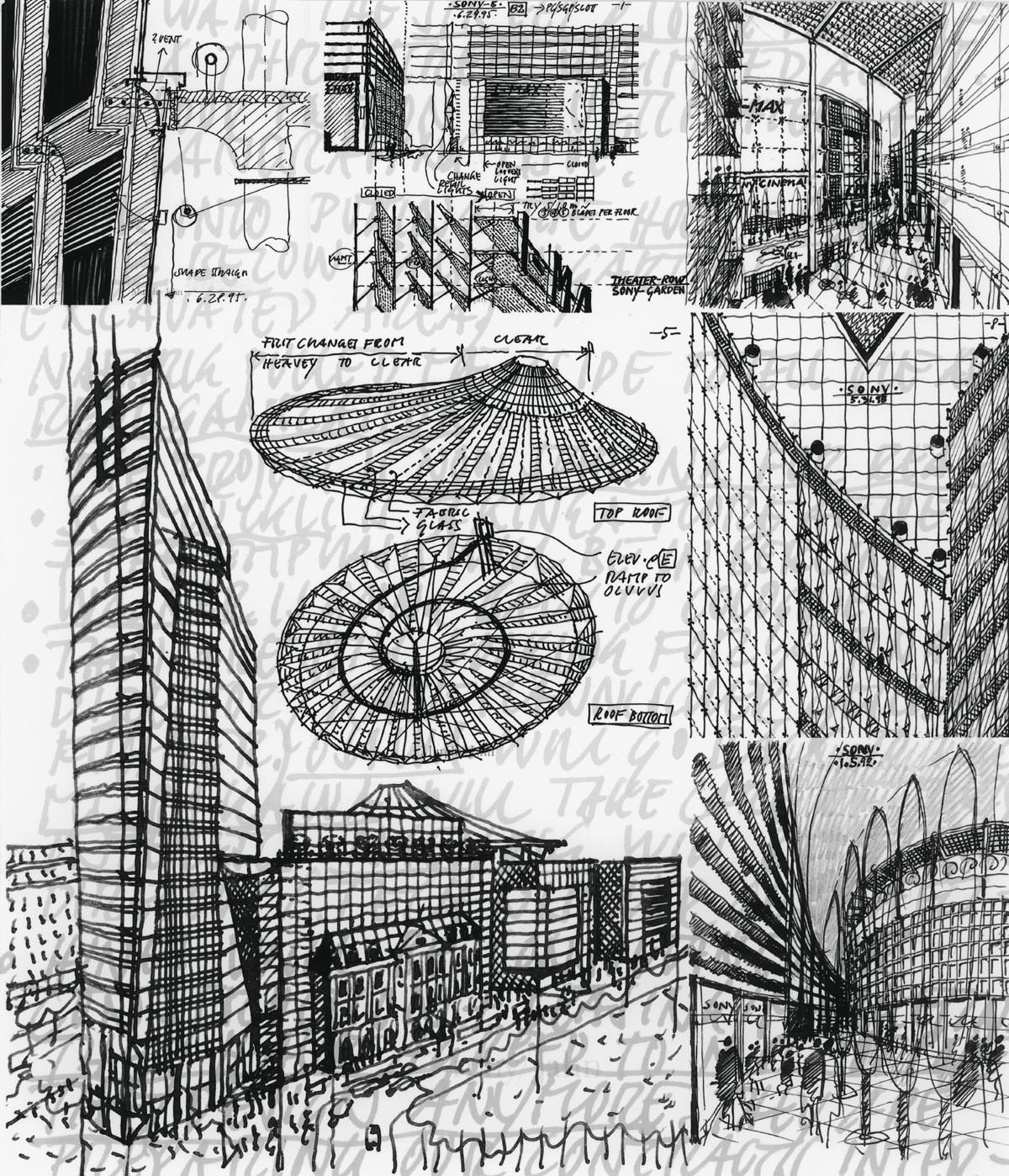

However, in her book Eminent Architects, Kruse photographed exclusively architects: Zaha Hadid, Frank Gehry, Tadao Ando, Norman Foster, Álvaro Siza, and Peter Eisenman, assembling 32 of the most prominent in recent times. In this book, her portraits are accompanied by sketches or short, handwritten statements by the architects, sometimes alongside images of architectural models. Out of the combination of faces, handwriting, and projects, an examination of the architects’ artistic thoughts emerges – an abstract idea, an essence, attains a contour.

Luise Rellensmann visited Ingrid von Kruse at home in her Hamburg apartment to find out more.

-

![]()

Norman Foster in his office![]()

Frau von Kruse, why have you chosen to make portraits of architects?

Subjects cannot be sought. They must come to you. Some time ago I suffered a very difficult loss – my husband was killed in an accident. Friends encouraged me to distract myself with a new subject. On a trip to Cologne I went to the Arp Museum in Rolandseck, built by Richard Meier. That museum inspired me very much; I thought it was marvelous how the light and shadows came through the windows. The next day, I took portraits of Tony Cragg, a well-known English sculptor and the rector of the Kunstakademie in Düsseldorf. He was making a sculpture park in Wuppertal at the time. There was a listed anthroposophic house on the property, built by a student of Rudolf Steiner. Neither of us liked it at all. Cragg said: “Norman Foster said it’s a jewel. You should also photograph him.”

-

![]()

![]()

Mario Botta

-

![]()

![]()

And that’s how the idea was born. I thought, here’s a subject that interests me and would mean a lot of traveling, which is something I enjoy doing very much.

What fascinates you about architects?

Architects are not philosophers; they are doers. They have ideas in their head that they turn into reality using modern technologies. And what I find particularly enthralling is that the result is sometimes very questionable.

What do you mean by that?

It’s crazy what is built sometimes. It seems like as much as possible is made of glass. Those glass palaces sometimes seem like tears. In the wonderfully beautiful Getty Museum and Research Institute in Los Angeles, for instance, the blinds are lowered early in the morning in February. Nevertheless, it’s still so bright that the employees need to put on sunglasses. It makes me wonder how much the inhabitants’ psyches and bodies are taken into account in such designs. Things are built just because, say, Richard Meier wants to realize his idea. Or take Zaha Hadid’s MAXXI museum in Rome. With its concrete stairs and curved walls it seems very brutal – and is not at all suitable for exhibitions. Architects should build museums and not monuments to themselves! But there are also architects who embrace responsibility and build for the people. David Chipperfield is one of them, in my opinion.

How did you make the selections for your portrait book?

I’m not at all at home in the architectural scene.

Gottfried Böhm and the model of his design for the Hans Otto theater in Potsdam.

-

![]()

![]()

So I thought I should choose the Pritzker Prize winners – that’s manageable. And then there were other well-known architects, like David Chipperfield, Mario Botta, and Santiago Calatrava.

How did you approach the architects?

I sent a handwritten letter to each of the architects. I thought it would stand out and won’t be so easily discarded. The architects were then able to view my website to get an impression of my work, and to see everyone who I’ve already photographed. Viewed in the broader context, the architects are surely not at the topmost level of people I’ve used as subjects. Maybe that’s why they all agreed.

Your book is dominated by men; there are only a few women in it…

That’s right. I find that odd and also distressing. It’s really very hard to find a woman who is all the way at the top of the architectural hierarchy.

Von Kruse about her picture of Zaha Hadid: “It’s an unusually beautiful picture of her. She was very pleased with it. Until then, there were hardly any good pictures of her. That’s also because Zaha Hadid often flirts with her un-shapeliness.”

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

And when you do, they are exceptional people like Phyllis Lambert, who was a student of Mies van der Rohe. Her wealthy father built the Seagram Building in New York, and she later invested his money in architecture and founded the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montreal.

You have also photographed Zaha Hadid…

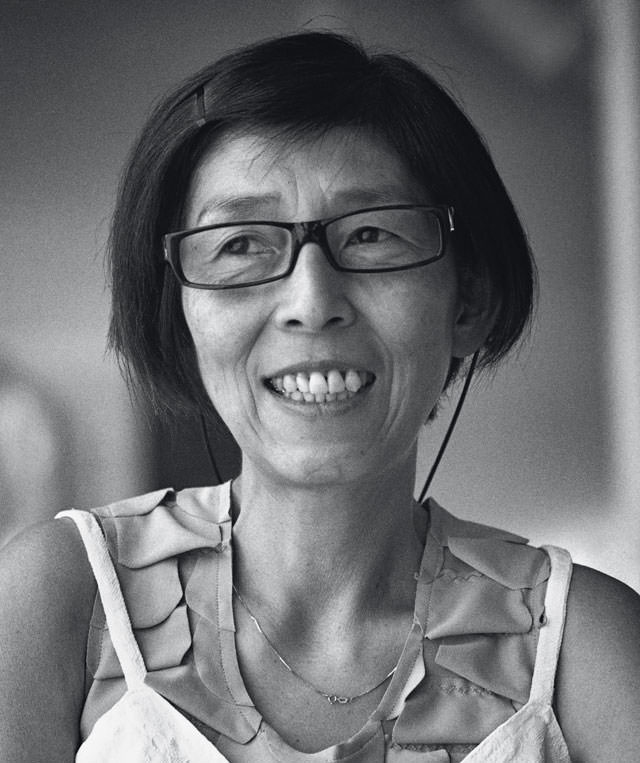

It’s an unusually beautiful picture of her. She was very pleased with it. Until then, there were hardly any good pictures of her. That’s also because Zaha Hadid often flirts with her un-shapeliness. In any case, I don’t believe she has any problems with her appearance. She is so well known that she can simply ignore such criteria. One thing is clearly evident in my photos of Hadid, Lambert, and also Kazuyo Sejima: they’re all strong, tough women with great self-assertiveness. That’s undoubtedly needed in their milieu.

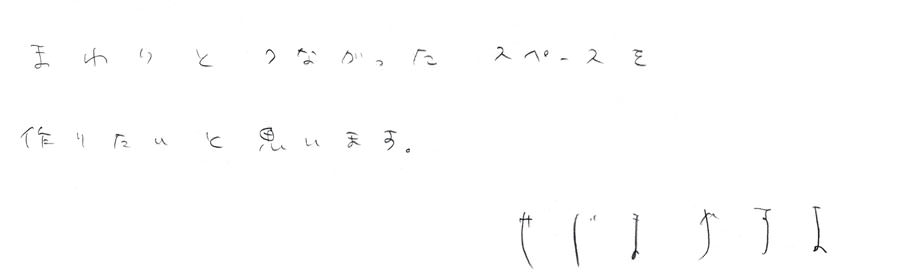

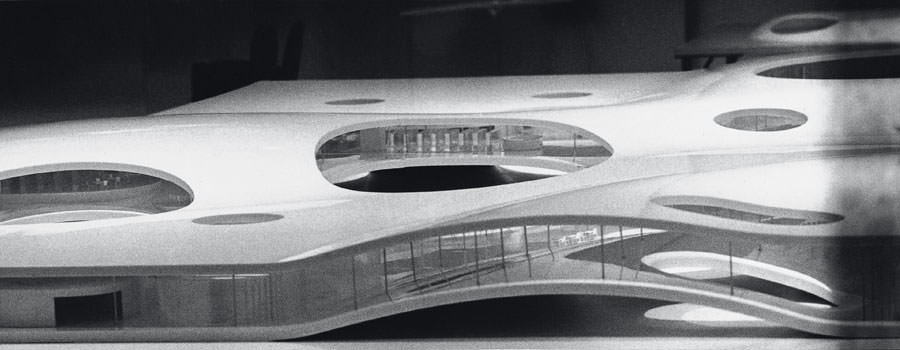

Kazuyo Sejima, the model of SANAA’s Learning Center in Lausanne, and Sejimas handwriting.

-

![]()

Sketch by Phyllis Lambert of Frank Lloyd Wright in his rooms at the Plaza, 1955.

(Photo: CCA, Montreal, Canada) -

![]()

Phyllis Lambert together with her big, black dog, Eros.

![]()

Something that also stands out is that most of the architects you portray are old. Do you think faces are more fascinating when they’re marked by the signs of age?

Yes. Old faces tell better stories.

Did you specify particular locations for the shootings, or did you let the architects decide?

I wanted to photograph all of them in their own environments – in their offices. Of course that wasn’t always possible, so there are exceptions. With Tadao Ando, for example, who was the first one I photographed. At the time he was renovating the Punta della Dogana in Venice for François Pinault’s collection. I met him there on the building site. I met the architects from SANAA in their Rolex Learning Center in Lausanne, shortly before the opening. I also wrote in the book about our encounter in this incredibly well-balanced building, with its glass-enclosed meeting rooms and ramp-like connections instead of stairs.

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

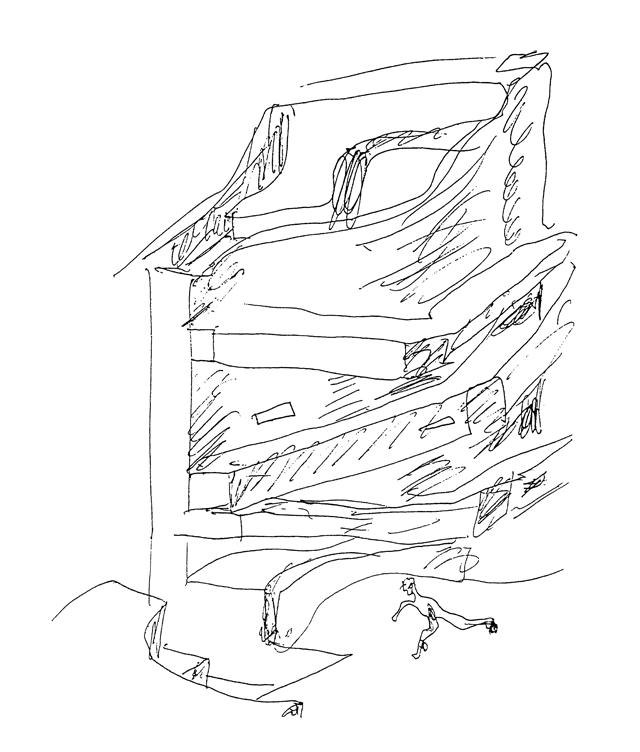

David Chipperfield, his handwriting and a personal sketch of his new, central entrance building of the Museumsinsel in Berlin.

-

![]()

Helmut Jahn

Was that the most unusual location for you?

Mario Botta’s studio tower in Lugano impressed me very much. It’s built of brick and wonderful slate and marble. He has his studio on the two middle floors. The windows are placed all around like portholes, and the offices for individual architects are placed like slices of cake around the gallery in the center. It was also interesting at Peter Zumthor’s office. Everything seemed to be hermetically sealed. As if he wanted to wall himself in and make access for others as difficult as possible. There were dark, steep stairs in his studio; I stumbled a few times. What’s more, I had to take off my shoes and put on slippers.

Who had the most chaotic office?

Norman Foster said to me: “Everyone has his own shell where he can be creative.” And the differences are really great. After Richard Meier’s office, where everything was snow-white, I went to Peter Eisenman’s. There, old cardboard was lying all around and nothing was nicely painted. From there I went on to Rafael Moneo’s office.

![]()

-

![]()

![]()

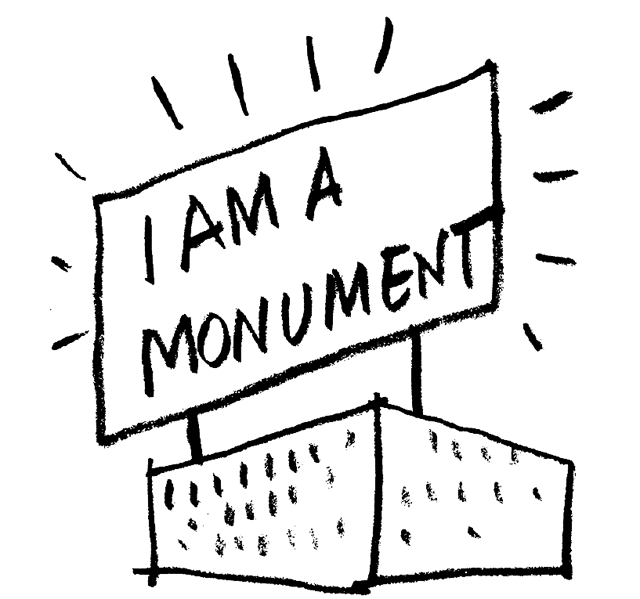

Robert Venturi and Denise Scott-Brown

-

![]()

I am a Monument, the almost iconic drawing from Venturi & Scott-Brown’s “Learning from Las Vegas” book.

-

When I arrived there, I thought at first that I was standing in front of the wrong building. I was completely bewildered – bits of paint were peeling off and the gate to the garden hung askew. Nevertheless, Moneo is a fine old gentleman, who worked in an orderly, precise, and very conscientious manner. That’s recognizable in his extension to the Prado. But to photograph his models, I had to go into the attic, where everything was lying around. Seeing the individual architects’ surroundings was a very interesting experience indeed. I found it reassuring to find a junk room!

What was your time frame for completing the project?

It took two and a half years from the first photo to the printed book. During one and a half of those years I merely traveled and took photographs. A terrific experience.

Architects are always in a rush. Did they make sufficient time available for you? Or did everything have to be done quickly?

I generally had enough time. But architects really think they’re the busiest people in the world. I can’t vouch for that. Because when I think of great politicians, for instance – they are faced with entirely different challenges, also with a different responsibility. It really is a peculiar image that the architects have of themselves. And there are only a few who don’t overtly act the part – Richard Meier, for example. Eisenman and I. M. Pei also didn’t continually emphasize how busy they were.

What camera do you use to take your photographs?

I take pictures the old-fashioned way: with an analog Hasselblad. I have no studio. I prefer traveling to my subjects than having them come to me. I always take black-and-white photographs and develop the film myself. I rent a basement where I do all the darkroom work. It’s all very primitive. I like that.

With all your experiences with architectural personalities, were you able to discover a characteristic common to all architects?

Maybe their fashion. All of them wore modern watches, most of which are also visible in the photos. Many love wearing a black sweater.

![]()

-

Think Like

a Teenager»How is it that the architectural visualization industry does not grasp the reality that thirteen-year-old children understand? ...Think like a teenager – do not post photos of yourself with a spotty face.«

![]()

-Trond Greve Andersen, CEO of MIR rendering company

(as quoted in CLOG’s August 2012 issue) -

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Positive Press

Getting Vila Cruziero on the cover of every newspaper with a positive message change the perception of the public.

- Dre Uhrhan of Haas&Hahn (www.favelapainting.com)

Dre Urhahn and Jeroen Koolhaas’ Favela Painting Project altered the public image of the Vila Cruzeiro favela in Rio de Janiero through a simple coat of paint. By changing the perception of the place, in this case an impoverished slum, a community’s understanding of itself can also change. Paint may be superficial, but its effects are not shallow. Here lies the power of constructing self-image.

![]()

![]()

-

Modern Ruins

A Topography of Profit

Photographs by Julia Schulz-Dornburg

Text by Rob Wilson

-

Julia Schulz-Dornburg:

Ruinas modernas. Una topografía de lucro

Editorial Àmbit Servicios Editoriales, S.A. Barcelona, 2012

ISBN 978-84-96645-14-1

www.juliaschulzdornburg.comIn Berlin until May 9, 2013:

Modern Ruins - a Topography of Profit

A photographic inventory by Julia Schulz-DornburgAedes Am Pfefferberg, Christinenstraße 18-19, 10119 Berlin

www.aedes-arc.de

In Madrid until June 9, 2013:Spain Mon Amour - Ruinas Modernas

Museo ICO, C/Zorrilla 3, 28014 Madrid

www.fundacionico.es

These photographs form part of a research project undertaken by Julia Schulz-Dornburg to document abandoned housing and leisure complexes around Spain, speculative developments that were abandoned after the property bubble burst in 2007-08. Schulz-Dornburg travelled 10,000 kilometers and documented over 60 examples during her research, supplementing her documentary photos with aerial shots, development plans and original promotional material, including florid quotes from the original developers' brochures (some of which we also include here).

The buildings pictured here are not the detritus of some apocalyptic natural event – like Pompeii after Vesuvius – but of human greed: destroyed by the very economic system that engendered them. The literal and metaphorical hollowness of these human endeavors perfectly echo the closing line of T.S. Elliot’s 1925 poem The Hollow Men: “This is the way the world ends / Not with a bang but a whimper.”

Schulz-Dornburg’s research formed the basis for her book Ruinas modernas: Una topografía de lucro, and two current exhibitions on show at Museo ICO in Madrid and at Aedes in Berlin.

-

![]()

The remains of the completed infrastructure for a complex of luxury dwellings for over 500 residents, beside the River Tormes. Just two pilot houses were completed before all construction ceased in 2007. (Camino de las Viñas, Alba de Tormes, Salamanca, 2004-07)

Alba Marina Residential

Complex:»Residential development with sailing club,

table-tennis courts and covered swimming pool.«![]()

These are the remains of the completed infrastructure for a complex of luxury dwellings for over 500 residents, beside the River Tormes. Just two pilot houses were completed before all construction ceased in 2007. (Camino de las Viñas, Alba de Tormes, Salamanca, 2004-07)

-

The site of the stalled Alba Marina Residential Complex, 2004-2007, showing the extensive views overlooking the River Tormes to hills beyond.

-

![]()

A parade of forever half-built terraced housing snakes along the brow of a hill. (Pego, Alicanteas, 2001-2008)Urbanization

Bella Rotja:»A privileged place in which to

discover the very essence of this land.« -

![]() Skeletal buildings greet you at a crossroads.

Skeletal buildings greet you at a crossroads.Residential Cármenes

del Suspiro»Enjoying success in a refined high-level ambiance.«

-

Residential Cármenes del Suspiro: ruins with a view. (Municipality of Dílar, Granada, ?-2009)

-

![]()

These unfinished shells of houses are the remains of a plan which envisaged a residential community of 326 dwellings next to golf courses, a hotel and spa, an ‘aparthotel’, a riding school, quad-bike circuit with additional facilities for hunting. (Villamayor de Calatrava, Ciudad Real, 1993-2009)

Calatrava Tourist and Leisure Complex

-

A road to nowbere. The Calatrava Tourist and Leisure Complex, Villamayor de Calatrava, Ciudad Real, 1993-2009.

-

![]()

A residential development of 140 units which was abandoned without having any surrounding infrastructural work. (Estepona, Málaga, 1998)Dominion Heights Estate

-

A bit of gardening needed? Dominion Heights Estate, Estepona, Málaga, 1998.

-

![]()

Half-finished hillocks of the once-planned 3000 chalets, mimic the adjacent landscape and overlook a golf-course which is gradually returning to the desert. (Calle Pacífico, San Juan de Terreros, Pulpí, Almería, 1990-2010)

Golden Sun Beach & Golf Resort:

»Chalets with 2 and 3 bedrooms, situated in an attractive resort built on high ground that lets you enjoy some incomparable sea views.«

-

Golden Sun Beach & Golf Resort, Pulpí, Almería, 1990-2010

-

![]()

This development was planned to contain over 2,500 dwellings, which would have more than quintupled the population of the local municipality. After many of the units had already been sold off-plan, the developer went bankrupt, the planning agreement to urbanize this virgin land was declared null and void, and the land is gradually returning to its rural condition, be it now dotted with the concrete carcasses. (El Barril, Campos del Río, Murci, 2004-09)

![]()

Trampolin Hills Golf Resort

»In its eagerness to achieve the maximum comfort for its clients, homes have been built to create a little paradise for you and your family.«

-

The investor was dreaming of a “little paradise for you and your family”: Trampolin Hill, El Barril, Campos del Río, Murci, 2004-09

-

![]()

Economic crisis and the abandonment of development in Spain, as reflected in the work of Julia Schulz-Dornburg

Text by Ethel Baraona Pohl

The

Contradictory

Encounter OfThe Full

With

the Empty

In Spain, as in many other European countries, we have witnessed over the past five years how recession and economical decline have constricted the way we live, particularly in regard to housing and shelter. And with the pervasive downturn in the economy sparking both political and ethical crises, one of its clearest manifestations has been the proliferation of abandoned buildings seen across Spain, which have been documented by Julia Schulz-Dornburg in her series of images “Modern Ruins.” The impact of these images is strong, as strong as the image of an eviction can be, because they represent the crisis of values we’re immersed in now due to our capitalist approach to life. “Modern Ruins” represents the ruins of political thought.

-

This photographic work is a demand for re-questioning our identity, our notions of collectivity, our social and cultural needs. Every single image here becomes part of a cadavre exquis which gathered together bear painful witness to a failed opportunity. Schulz-Dornburg has been making images to record the recent past, so it forms part of our memory keeping alive mistakes made so that it helps us react and start taking action to prevent future corruption and speculation. The world in flux presented by Schulz-Dornburg’s photos requires the active participation of the viewer, a complicity and understanding of a message that is indeed a manifesto in itself – but a manifesto of contradictions, of uncertainty, of the unfinished. As Sarah Wigglesworth recently pointed out, “Considered objectively, there is always the same amount of

»It seems like all those years – the years of speculation, of fast economic growth, of failure – we were living in a constant state of horror vacui, when every single square meter of territory was parceled out to be built on.«

space around us.” And it’s up to us how to use it. Looking at these photos, it seems like all those years – the years of speculation, of fast economic growth, of failure – we were living in a constant state of horror vacui, when every single square meter of territory was parceled out to be built on, to become one massive edifice. In this context, the work of Julia Schulz- Dornburg is also creating a record of the economical crisis, showing through her research, this contradictory encounter of the full with the empty, to visually present the affliction of a country – its territory full of empty buildings, exploring what lies behind this evident decay.

But beyond the recurrent discourse about the crisis in Spanish, it’s interesting to think how to respond to the current situation.

-

»[he taught] that over time the movement of the yielding water will overcome the strongest stone.

What’s hard – can you understand? – must always give way.«

Bertolt Brecht, Poems, 315If a few years ago property speculation was the hard [in the Brechtian sense] albeit it in the hands of a small percentage of the population, what the hard is now is the energy that emerged as a reaction to those years and its clear manifestation in movements like #15M or the group Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca (PAH), who are working to stop and transform the foreclosure processes and housing evictions and even to force the legal frameworks to change. In the present unfolding situation, visual archives like “Modern Ruins” are very valuable. They present the evidence of the systemic failures of capitalism and lay out for us an extensive landscape both for our imagination – and for action. As Frederic Jameson outlined in his book Archaeologies of the future, our imaginings are all collages of experience, constructs made up of bits and pieces of the here and the now. Following on from this idea it is fundamental to recognize that we are even now tracing paths to the future, ones composed of all these pieces segregated into a new territory that is trying to recover from those lost years.

The utopian city has always been a dream, but as Walter Benjamin wrote “The history of dreams is still to be written. Dream participates in history.” In a country where it has been estimated that there are more than 20,000 skeletons of unfinished buildings, the work of collectives such as Todo por la Praxis and their project increasis give us clues about how to fight for that dream. Whilst Julia Schulz-Dornburg has given us a lead, providing us with the references and places through her images and research, architects should now become part of this new citizen laboratory, to help develop strategies for the activation of these disused buildings in order to create new selfmanaged facilities and provide services for the existing neighboring communities that lie adjacent to them.

![]()

»Architects should now become part of this new citizen laboratory, to help develop strategies for the activation of these disused buildings in order to create new self-managed facilities…«

-

Triumph of the Spectacle

»Forty years after La Société du Spectacle, it is now obvious that the image has gained the upper hand: our age prefers the image to the thing, representation to reality: the image has acquired the character of reality.«

- Emiliano Gandolfi, The Image and its Double, 2006.

As quoted in Concrete: Photography and Architecture, 2013.

(Photo: F.C. Gundlach, 1966)![]()

-

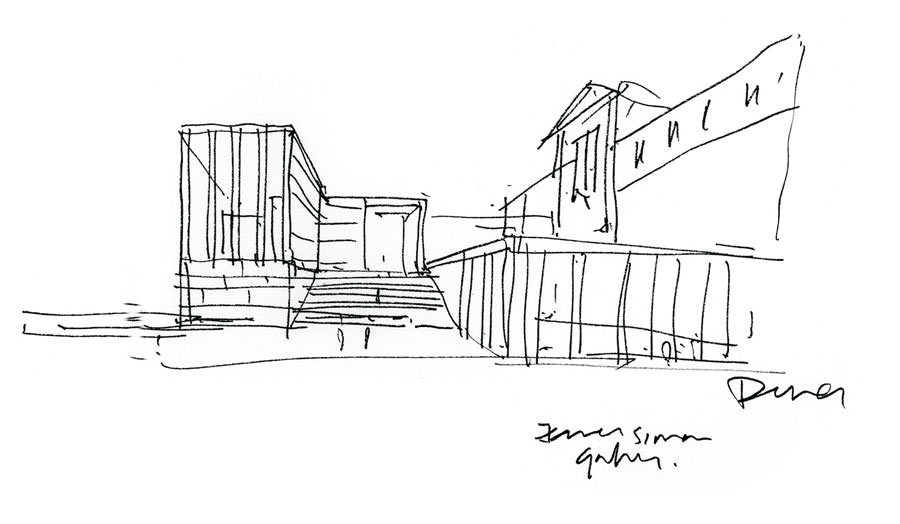

In the Photo Booth with ...

Roger Diener

The Common Pavilions exhibition curated by Swiss architects Diener & Diener was one of the highlights of the 2012 Venice Architecture Biennale. The small show put the focus on the 30 exhibition pavilions spread over the Giardini, structures that are often almost overlooked by visitors to the Biennale as they dive from exhibition to exhibition. Common Pavilions is on view in Berlin at Aedes Architekturforum until May 9th, and its opening gave us the perfect opportunity to welcome Roger Diener into our photo booth.

Interview by Florian Heilmeyer

![]()

![]()

-

Why did you decide to focus on the national pavilions in the Giardini?

We wanted to interpret David Chipperfield’s general theme – “Common Ground” – differently: more as the space in which we talk about architecture together. How do we discuss and debate architecture? How do we perceive it? So it seemed natural to do something with the national pavilions in the Giardini. This way we were also able to highlight the buildings, which the visitors often only perceive marginally as exhibition showcases.

-

You invited a different author to describe each pavilion, in an essay. Did you give them any guidelines about what the essays should address?

The authors were given complete freedom to approach the subject as they chose. Above all, our exhibition is meant to offer different perspectives. That’s why the authors wrote in their native languages and why the essays were also recorded, spoken either by the authors themselves or by a professional narrator. They are available on the exhibition website, so you can listen to the essays on a smartphone while you walk around the site. For us, listening and experiencing the site is a very important aspect.

-

In contrast to the texts, you had all the photographs taken by a single photographer, Gabriele Basilico.

Yes, because we wanted to supplement the visitor’s often-fleeting glance at the exterior of each pavilion with the extremely precise view of someone like Gabriele. These photos are arranged in the exhibition as in a reading room – not fixed on the wall in a given order, but placed freely on shelves along the walls. So some of the photos are behind others, replicating in a way the superimposed perception of the individual buildings in the Giardini.

-

Very sadly, Gabriele Basilico passed away just a few weeks ago. His choice to photograph the Giardini pavilions in stark black and white could perhaps be interpreted as an awareness of his close death.

It was great to complete this project together. Gabriele was indeed pushing all of us to finish the book, because he feared his strength could wane quickly; it was clear to him that this would be his last work. But his reasons for chosing black and white were very specific and very different: Gabriele told me he must photograph the pavilions like this because the entire grounds of the Giardini are so dilapidated. Color photographs would have emphasized this neglect, whereas black and white images stress the aging grandeur of the buildings. It’s a way of conferring nobility upon the pavilions: I hope that comes across in the double-page photos in the catalogue.

-

Roger Diener (*1950) established the firm Diener & Diener in 1980, continuing the original established in 1948 by his father, Marcus Diener. He is a Professor at the Swiss Federal Polytechnic (ETH Zurich), Studio Basel: Contemporary City Institute, where he has been teaching since 1999. In 2002, the Académie Française awarded him its Architecture Award for his work.

His practice is known internationally for projects such as the Warteck Brewery residential buildings in Basel, Switzerland (1996), the Swiss Embassy in Berlin, Germany (2000), the Forum 3 Novartis Campus in Basel, Switzerland (2005) and an extension of the Museum of Natural Science of Humboldt University in Berlin, Germany (2010).

Exhibition:

Common Pavilions

22 March – 9 May, 2013

Aedes Am Pfefferberg

Christinenstraße 18–19, 10119 BerlinCatalogue:

Common Pavilions: The National Pavilions in the Giardini of the Venice Biennale in Essays and Photographs

Edited by Diener & Diener Architects with Gabriele Basilico

Photographs by Gabriele Basilico

Scheidegger & Spiess Publishers, Zurich, 2013

Texts in English and 23 other languages

Hardcover, 328 pages

Do you have a favorite pavilion?

The longer you look at them, they are all great. Yet I can’t help but love the Nordic Pavilion by Sverre Fehn. It’s the cathedral among the pavilions.

![]()

-

Ruins: Documents of Contemporary Art

Edited by Brian Dillon

Published by Whitechapel Gallery

Softcover, 240 pages, no illustrations

ISBN: 978–0–85488–193–2Finnish Architecture with an Edge

Edited and written by Tarja Nurmi

Photographs by Kari Palsila

Published by Maahenki, Helsinki, 2013

Hardcover, 215 x 275 mm, 280 pages

ISBN: 978-952-5870-69-5

![]()

![]()

Part of Whitechapel Gallery’s current Documents book series, which considers key themes and ideas in contemporary art, this anthology of extracts and essays unravels and explores the recent obsession with decay and so-called “ruin lust” in art, architecture, and cultural practice. The book is clearly organised in four sections: “Modernity in Ruins,” “The Military-Industrial Sublime,” “Drosscape,” “The Future Now,” showing how the idea of the ruin has been institutionalised and transformed from a product of a utopian failure into a subject of inspiration and interest. One downside is that the book contains no images as reference – although, conversely, this also makes it a rich exercise for the imagination. (gl)

With thoughtful texts and packed with pictures, this book acts as a useful primer for recent key projects and developments in Finnish architecture. It includes recent housing, transport, commercial, educational and cultural projects, but also looks further afield to Finnish practices working abroad, in particular the extraordinary scale and materiality of the recently-completed Wuxi Grand Theatre on the shore of Lake Taihu, China by PES-Architects. (rw)

![]()

-

Encyclopedia of Flowers

Flower Works by Makoto Azuma

Photograhs by Shunsuke Shiinoki

Lars Müller Publishers, 2012

Paperback in transparent slipcase, 16.5 × 24.8 cm, 512 pages, 203 color illustrations, English

ISBN 978-3-03778-313-9

Stun-ning-ly BEAUTIFUL. Rarely are images of death this haunting, or simultaneously suggestive of life and rebirth. This volume is a record of the Japan-based image work created by the flower arrangements of Makoto Azuma and the photography of Shunsuke Shiinoki, going far beyond images into the reality of our human environment and its flora. Azuma and Shinoki’s work is about cycles of existence, cultivated nature: with the number of newly-invented flowers too numerous to name; and unstable, human-influenced nature – as cherry blossoms worldwide become mysteriously whiter. The images are still as death on the page, but are riotous representations of life, radiating something true and deep about the realm of the soul, poetics, aesthetics. The notes for “Whole,” a section of the book, sum up the rationale behind the Encylopedia: “Any sense of seasons, the particularity of a climate, or the special quality of a breed no longer possesses a fixed definition. Chaos. A microcosm of the world we live in.” The lush hyperstatic photographs contain mixtures of cultivation, manipulation and virgin nature as complex in the miniature as any city, any landscape, anything wrought by the natural and, in the end, human hand. (jb)

![]()

![]()

-

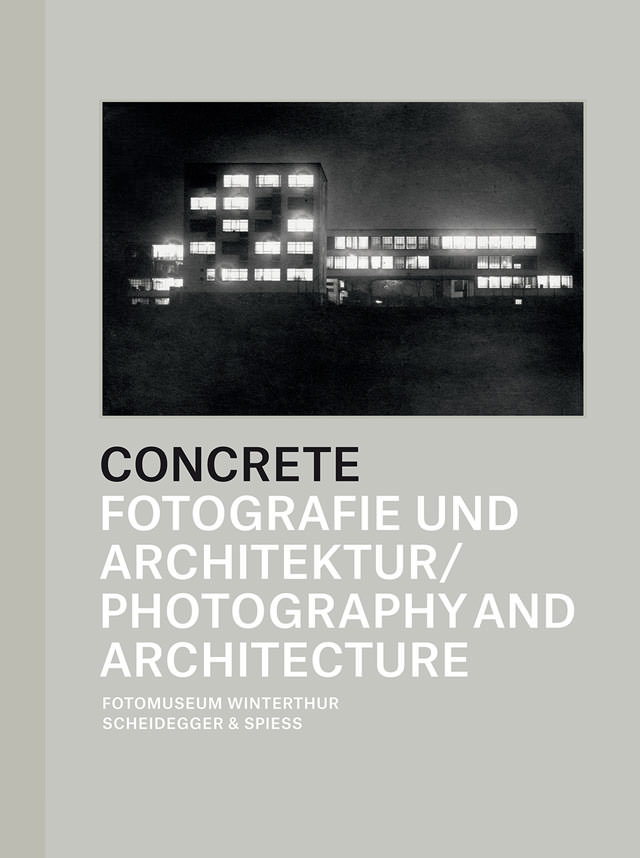

Concrete: Photography and Architecture

Edited by Fotomuseum Winterthur

Scheidegger & Spiess, 2013

Text in English and German

Hardback, 21 x 28 cm, 440 pages, 156 color and 157 b/w illustrations

Concrete: Photography and Architecture offers an enjoyable and surprising roller coaster ride through almost 200 years of "taking pictures of buildings.“ A rather idiosyncratic structure with chapters going from “Power, Boundaries, Security” to “Paris” and from “Construction, Decay, Destruction” to “Calkutta,” it includes pictures from Joseph Nicéphore Nièpces, Julius Shulman, Candida Höfer, Thomas Ruff, Andreas Gursky, Gordon Matta-Clark, Denise Scott-Brown and Robert Venturi, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Georg Aerni, and too many more to mention. Turning its pages is a constantly surprising ride indeed, spanning space and time and offering with its unusual combinations new perspectives on the big topic of how to put architecture (and sometimes people) in pictures. (fh)

![]()

![]()

![]()

-

![]()

-

![]()

-

Wood. Paper. Pulp. This one is about some pretty basic stuff, but we are also going to get a little wild… c’mon, we’re uncube. A little pulpy, a little irreverent – we’ll give you some really nice wooden stuff to gnaw on, then throw in a few other related things…

![]()

![]()

![]()

-

![]()

The

Dessau

EffectWhat is known today as the “Bilbao Effect” certainly didn’t happen for the first time when Gehry’s fishformed Guggenheim Bilbao opened in 1997. Times and circumstances were different, but when the German Bauhaus school moved from Weimar to Dessau in 1926, it had a similar effect on the city which lasts until today. We’ll call it the “Dessau Effect” for now.

The Bauhaus school was dedicated to modernism, intending to combine craft and fine art. From its founding in Weimar in 1919, its ideas attracted heavy criticism from conservative circles and when the nationalists took control of the state parliament of Thuringia in 1924, they cut the institution’s funding in half. So Walter Gropius, director of the Bauhaus from 1919-1928, started looking for a new home.

How the Bauhaus has defined the image of Dessau since 1926

![]()

“Junkers Luftbild”, postcard from 1926. (Photo: Courtesy Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau)

-

![]()

Postcard from 1938 when the Bauhaus school was already closed and the building used as “Frauenarbeitsschule”. (Photo: Courtesy Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau)

After only five years of existence, the Bauhaus was already an internationally acclaimed institution, so several German cities made rival bids to attract the school to relocate to them. The race was won by the smallest, Dessau, which was then a booming industrial town in the center of Germany. In the 1920s, this region was Germany’s Silicon Valley, inhabited by forward-looking industrials like Hugo Junkers, who had just developed the first aeroplane constructed entirely of metal. The interest from industry in the Bauhaus school and their formal and material experiments was reciprocated by the institution’s interest in further developing its ideas on the unity of art, technology and industrial mass production. When the new Bauhaus building, designed by Gropius himself, opened on the outskirts of Dessau in 1926, it definitively changed the image of the city. And today, the Bauhaus Foundation which now resides in the original building is a key element in this de-industrialized and shrinking city, which is trying to redefine its image now as the Bauhausstadt. Unlike Bilbao’s, the “Dessau Effect” has already been working its magic (with some interruptions) for over 90 years. (fh)

![]()

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Intelligence starts with improvisation.«

Yona Friedman

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents