-

Magazine No. 12

Into the Desert

-

No. 12 - Into the Desert

-

page 02

Cover

-

page 03

Editorial

Into the Desert

-

page 04 - 19

Framed Views

Denise Scott Brown on the desert, Ed Ruscha, and the Pritzker Prize she never received

-

page 20

Space Debris

-

page 21 - 27

Big Surf

Communing with the Mechanical Wave

-

page 28

The Neverwas Haul

-

page 29 - 31

Dubai Thriller

The world's largest fountain dances to Michael Jackson

-

page 32 - 34

Extra Dry, On the Rocks

-

page 35 - 43

Pooling Around

Swimming through the history of New York City

-

page 44

Into the Dessert

-

page 45 - 49

In the Photo Booth with...

Beatrice Galillee

-

page 50 - 51

Bookmarked

-

page 52

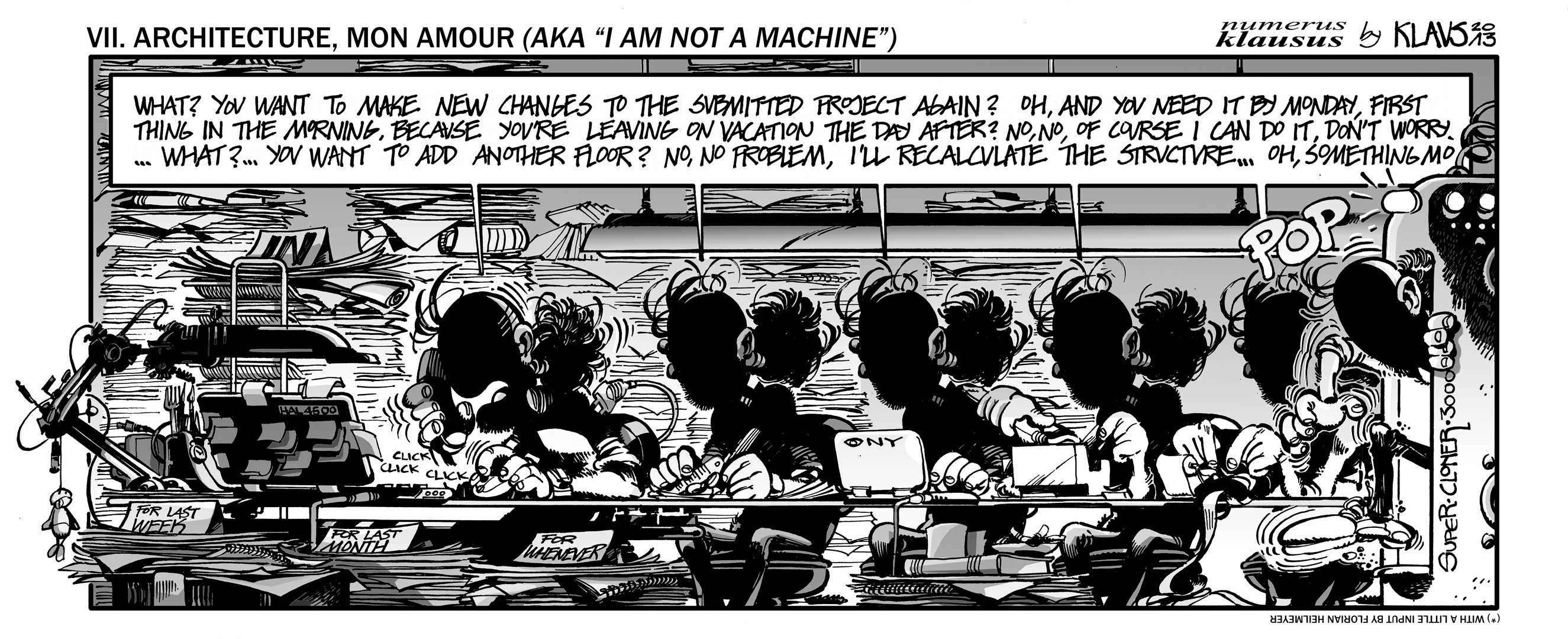

Klaustoon

VII. Architecture, Mon Amour

-

page 53

Next

Berlin. Where do we go from here?

-

-

uncube’s editors are Elvia Wilk, Florian Heilmeyer, Jessica Bridger, and Rob Wilson. uncube is based in Berlin and is published by BauNetz, Germany's most-read online magazine covering architecture in a thoughtful way since 1996.

What would you want to bring on a long trek into the desert?

If you take uncube with you, we guarantee you won’t get bored or thirsty – we’re bringing along the likes of Denise Scott-Brown, Beatrice Gallilee, even the cast(-offs) of Star Wars …and a pool (ice cream/cold pudding?) or two.

Follow us from Las Vegas to Dubai to the urban badlands ... We’re pushing through the heat haze in search of an oasis.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Cover Photo: Death Valley, 1965 © Denise Scott Brown

-

Denise Scott Brown on Ed Ruscha, the desert, and bitter old men

By Luise Rellensmann

Self portrait in the mirror, 1960. (Photo © Denise Scott Brown)

Framed

Views

-

It is easy to forget that Las Vegas is desert country. When Denise Scott Brown first entered the deserts of the American West, she brought her childhood in South Africa to bear on her experience there, in reading the landscape. Perhaps best known for the seminal book Learning from Las Vegas written along with Robert Venturi, her long-time partner, she has lately been thrust into the spotlight as a symbol of women’s struggle to become accepted into the canon of architecture. Scott Brown is an architect who saw an element of the built environment so clearly and communicated it easily to the outside, but there's more to the story. Luise Rellensmann met with Denise Scott Brown in Los Angeles to learn more about the images behind the text, and the story behind it all.

-

![]()

![]()

Denise Scott Brown has captured various land and cityscapes from California's Death Valley Desert to the urban streets of Philadelphia. (Photos: Denise Scott Brown)

-

Las Vegas. Photo: Denise Scott Brown

-

Luise Rellensmann: When was the last time you visited Las Vegas?

Denise Scott Brown: In 2009.

How did you happen to visit Vegas in the 1960s?

Out of my family tradition: I had seen my mother’s home movies of its lights, taken in the 1950s. Coney Island, Disneyland, Las Vegas – generations of our family had loved theme parks. Study experiences in South Africa and England. And my urban planning teachers on the East coast, social scientists like Herbert Gans and William Wheaton, who said: “Architects believe they know what’s good for people, but this is arrogance: You can’t afford to call Los Angeles and Las Vegas ugly; you need to understand why people like them. Why don’t you go there and find out?” So in January 1965 I did. This was the first of four trips I took to Las Vegas before I asked Bob [Robert Venturi] to join me there in November 1966. We taught our “Learning from Las Vegas” studio in 1968.

You were born in Zambia and raised in South Africa, and you have stressed that your view of Las Vegas is an African one. Bob is an American with Italian roots. How important were your different backgrounds?

I am African and Jewish. My family came from Latvia and Lithuania. My mother’s parents were from Kurland, a German-speaking dutchy within Latvia. Although from different continents, Bob and I shared an immigrant history and we fitted well into each other’s families. Our educations, Bob’s in the US and Italy, mine in those plus England and Africa, brought us to shared conclusions - but ones perhaps different from those of other architects.

-

South Africa, 1957. Photo: Denise Scott Brown)

-

When did you first start taking pictures and how did you become interested in photography?

Bob and I started photography in South Africa. He learned as a child from his father and taught me. Architecture school emphasized the importance of travelling to see the buildings we had learned about and of recording our experience for our future practice. During World War II travel was not possible and after it our distance from Europe made getting there expensive. We were also not welcome in some countries, owing to South Africa’s rightly-hated political system. In addition, the Apartheid government often removed the passports of dissidents. So our conclusion was: go abroad as soon as you can, stay as long as you can, get the further education you will need for practicing in Africa, and bring back a photographic record. But as we photographed, we moved beyond documentation of buildings and into observation of 1950s and 1960s phenomena that interested us — cultures not Culture, pop culture, counter-cultures, pop art, commercial architecture and signs — and photography itself as an art.

What were your major influences?

Conditions influenced us: environmental, archaeological, historical, political, social and cultural issues in Southern Africa. Artistic influences were multicultural and included the reactions to Africa of refugees from Germany under Nazi Germany. But I was drawn particularly to the art of rural migrants, to African folk/pop art that adapted traditional crafts to city life. They applied for example, beadwork and its coded messages to soda bottles rather than vegetable gourds. In England and Europe, post-war social schisms conditioned the artists and architects who inspired us, Brutalists, the Independent Group, and Team 10.

-

Here class was a major concern. Popular culture, a nascent Pop Art movement, and the Brutalists’ critique of Modern architecture and urbanism played roles. From these we learned that photography can document concepts as well as conditions, and we applied their photo techniques to our analyses of Vegas and Levittown.

To me, your photos show a great resemblance to the work of Ed Ruscha.

I love his work. I discovered his books in 1965 in a bookshop on Santa Monica Boulevard, and was intrigued that he was doing what I was doing. Shortly thereafter I chose his photographs of parking lots to illustrate an article “On Pop Art, Permissiveness and Planning.” And seeing his photo-composite of the Sunset Strip, I felt he had perhaps learned, as I had, from the traditional accordion-folded photo guides for tourists travelling down the Rhine. In 1952 I bought one of those for my Rhine trip and perhaps he did too. During the LLV studio we called the composite we made of our Strip an “Ed Ruscha.”

Have the two of you ever met?

Yes. Our Yale studio trip started in Los Angeles and I took the students to visit Ruscha at his studio. He and they got on well together. Back then he was hesitant to explain what he was doing, so they ended up drinking beer together.

![]()

Phoenix (USA), 1965. Photo: Denise Scott Brown»Architects believe they know what’s good for people, but this is arrogance.«

-

![]()

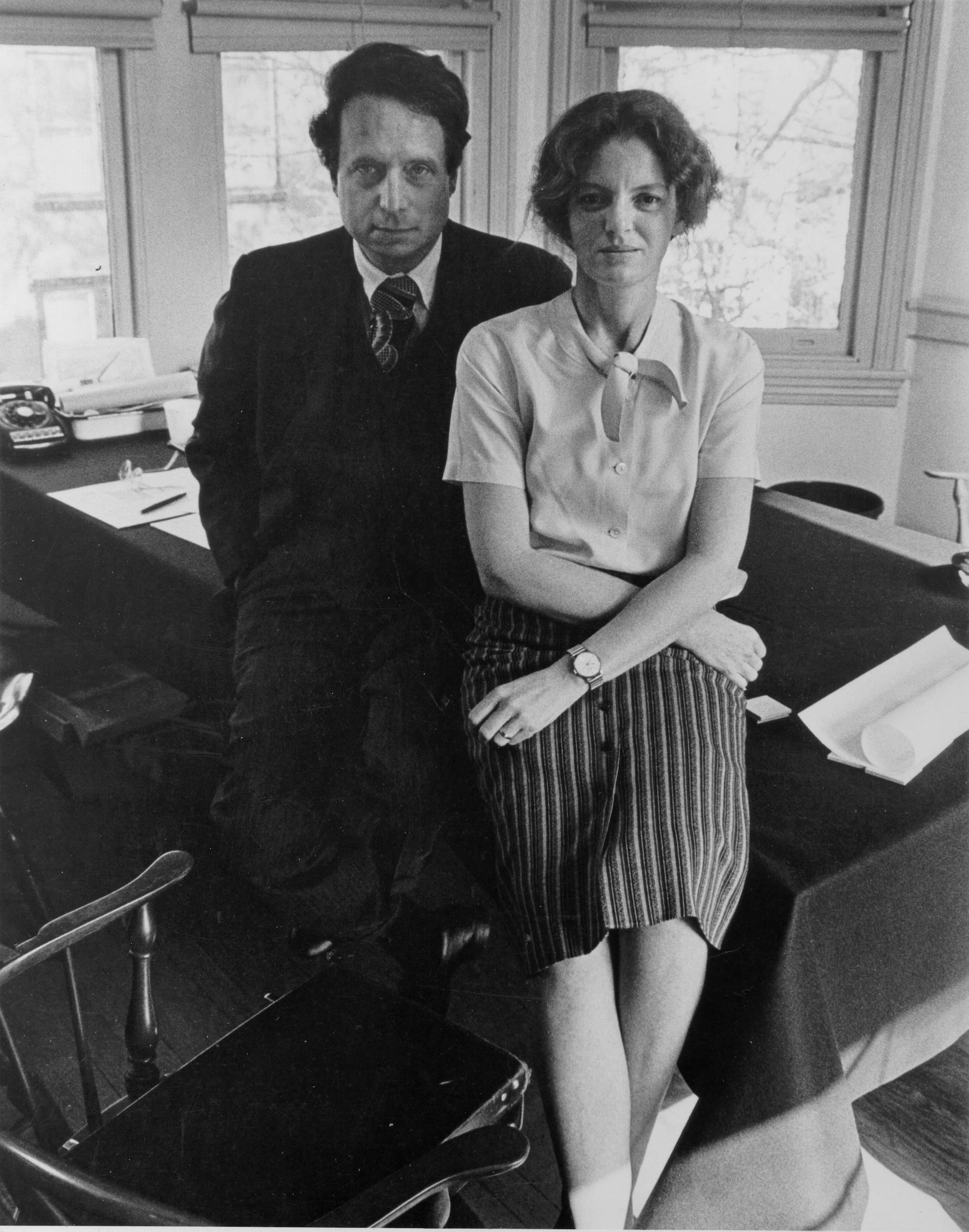

Denise Scott Brown circa 1960. (Photo: Denise Scott Brown/ Venturi Scott Brown and Associates)

-

![]()

![]()

Then and now: Denise and Robert have been married for over 45 years. (Photos: Cristina Guadalupe/Venturi Scott Brown and Associates)Talking about your role as mother and partner in an architecture firm: what was it like to stand up for your rights when you and Bob started together, and how different was the public’s perception of you as a female architect compared to today?

In the 1970s, “that did not happen” was the response of male architects when I said that Robert Venturi and I worked together on design. I would reply “How do you know? Were you under the table when we were working?” That infuriated them! On a New York discussion panel, Frederic Schwartz, project manager for my Miami Beach project, reproached a New York architect for referring to it as “Venturi’s project.” This man became incensed and stalked off the stage. But by mistake he walked into a closet and had to come out again. Although this caused laughter his huge anger convinced me that I could endanger our firm by speaking out, and I stopped for a while. I had written “Sexism and the Star System in Architecture” in the early 1970s but did not publish it until 1989. However, it was circulated in the independent press and used in women’s studies programs before that, and it still is. And I have been talking out for years, and of course there is still hostility.

-

Would a quota for women in positions of power in architecture firms change this situation?

US “affirmative action” law mandates roles for minority and woman-owned consultant firms on projects for government buildings. But the law seems to exclude large projects and I suspect it pressures minority and women-owned firms to remain small to afford the budgets they offer. But ways must be found to encourage and support minorities and women in architecture. The world and our profession will be livelier for what we offer, and our experience has been that diversity is fun, not a moral hair shirt.

How do you feel about the petition to the Pritzker Prize started by Harvard students Arielle Assouline-Lichten and Caroline James?

It’s been wonderful for me in many ways, but particularly because those who sign it passionately want a better world in architecture for women and men. Yet others disagree, and argue in the comment sections of online articles on the petition. I call them the “sad old white men.” I love old men (and women) but these are very bitter. They say “we can’t all marry the boss to get ahead.” Bob was not my boss! He and I were associate professors when we married. We had worked together as colleagues, even taught together, but never worked for each other. Others say, “he received the Pritzker Prize for work he did before he knew Denise.” This means they can’t have read C&C, where Bob thanks me in the early pages for my help. Some architects’ wives say: “What’s wrong with Denise? I’m happy to support my husband.” Well, I support mine too, and he supports me.

-

Photo courtesy of Venturi Scott Brown and Associates.

-

![]()

The Sainsbury wing of the National Gallery, London.

![]()

The University of Michigan. (Both photos: Matt Wargo, courtesy of Venturi Scott Brown and Associates)

Do you feel a special connection with any space you have designed? Which have met your expectations the best?

Of course I want my spaces to be beautiful — even if my definition of beauty may include “beautifully ugly.” And I’m more than happy when people tell us they find the atmosphere in our Sainsbury Wing helps them enjoy the art. But my heart jumps when I see people doing the things in my spaces that I had hoped they would do — when I have applied urban-derived concepts about relations between activities, and I see them working. As our project was nearing completion at the University of Michigan, the facilities planners sent me a message: “The students have torn down our construction fences. They have discovered your short-cut and are riding their bicycles across it.”

-

»My heart jumps when I see people doing the things in my spaces that I had hoped they would do.«

The Perelman Quadrangle Ampitheater in Philidelphia was designed by VSBA in 2000 and expands the original functions of Houston Hall across Wynn Commons into parts of the surrounding buildings. (Photo courtesy VSBA)

-

Denise Scott Brown (October 3, 1931) is an American architect, planner, writer, educator, and principal of the firm Venturi Scott Brown and Associates in Philadelphia, which she founded with her husband and partner Robert Venturi. Even after over fifty years as one of the most highly regarded architects, Denise Scott Brown still continues to publish and present her work.

Luise Rellensmann lives in L.A. where she currently works on issues of the conservation of Modern and Contemporary Architecture in Historic Urban Environments. Before moving to California, she lived in Berlin where she worked as an architecture critic for various media, and also at the Technical University in Cottbus, where her interest in the heritage and conservation of the contemporary past started.

![]()

If you could chose a place to conduct research today, would it be Vegas?

I keep thinking of research studios I would like to teach. One would investigate the train corridor from Philadelphia to New York, the landscapes you see along this 90-mile stretch. They are remnants of the biggest industrial center in the world — bigger than the Ruhrgebiet. These deserted early 20th structures have an elegiac beauty. But with Philadelphia’s population half the size it used to be, our economy can’t support them, and many contain hazardous materials. Yet you can learn much about architecture from them. And talented graffiti artists have made this stretch their museum. Shanghai is another rich opportunity. Its multicultural history is an obvious attraction, but its unusual building types would be interesting to consider for other locations. How would the lilong houses, derived from London mews, and the scholars’ gardens, small walled landscapes that suggest infinity, do in New York? There are many things I would like to consider but I am too old. So I set them down for others to investigate.

![]()

-

Space

DebrisVisual artist and film-maker Rä di Martino originally came across these sorry remnants of some of the film’s iconic scenes via google earth. So not in a galaxy far, far away — but still somewhere pretty remote: in the depths of Tunisia’s desert, around the Chott el Djerid salt lake.

They might not be a patch on the pyramids but these sci-fi set ruins definitely form a curious desert feature and Martino’s photographs poetically capture how the light-years have not been kind: time has caught up with these fragments of the future, gradually crumbling away to dust.

![]()

-

![]()

![]()

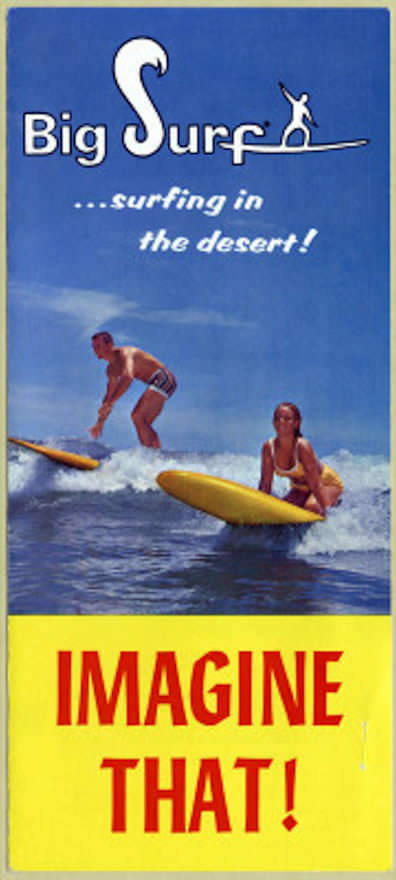

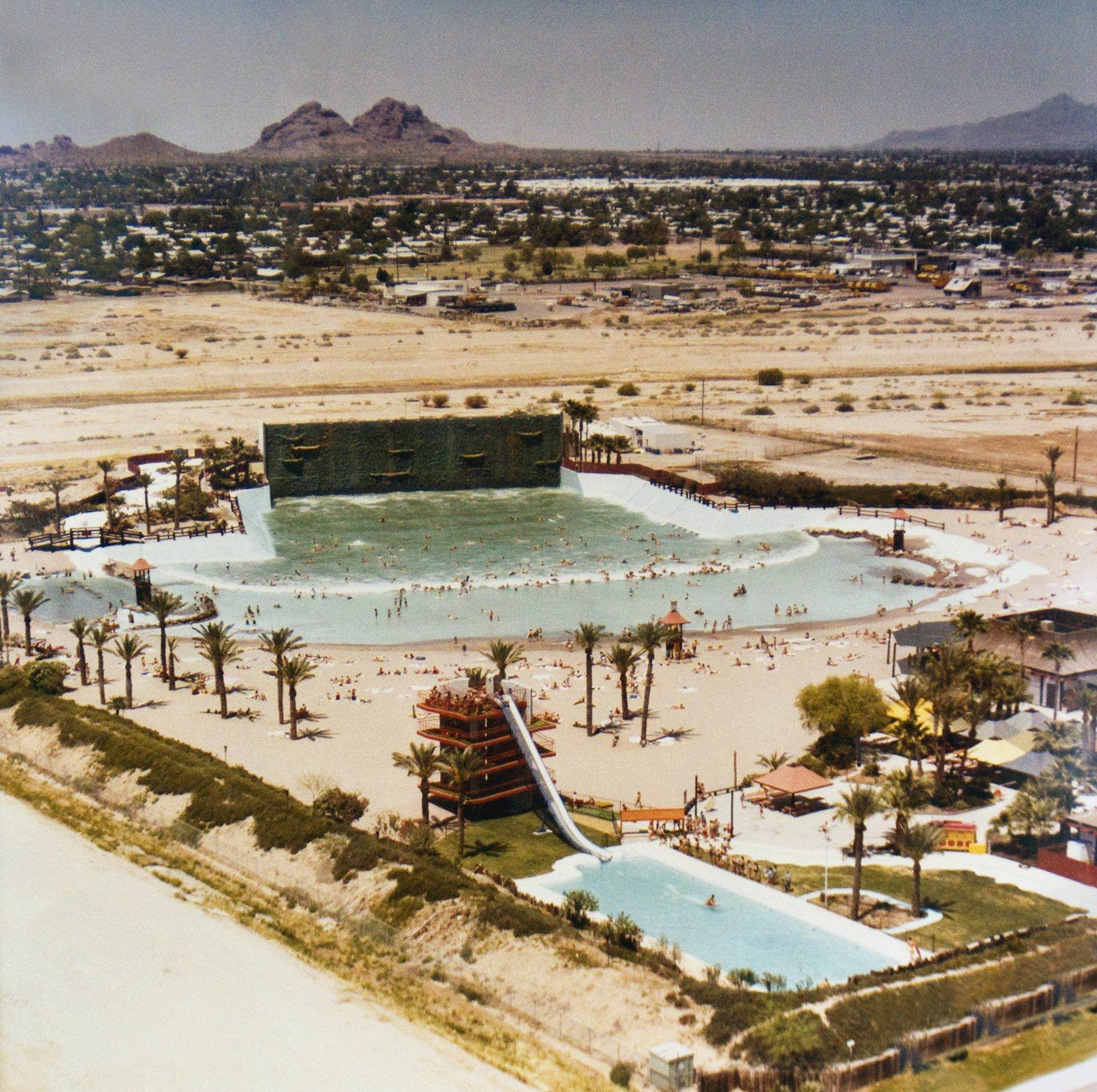

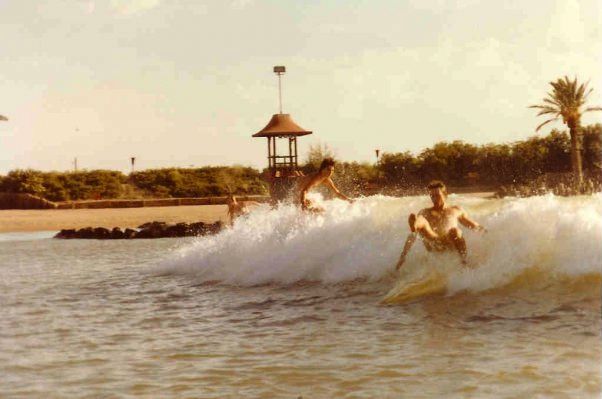

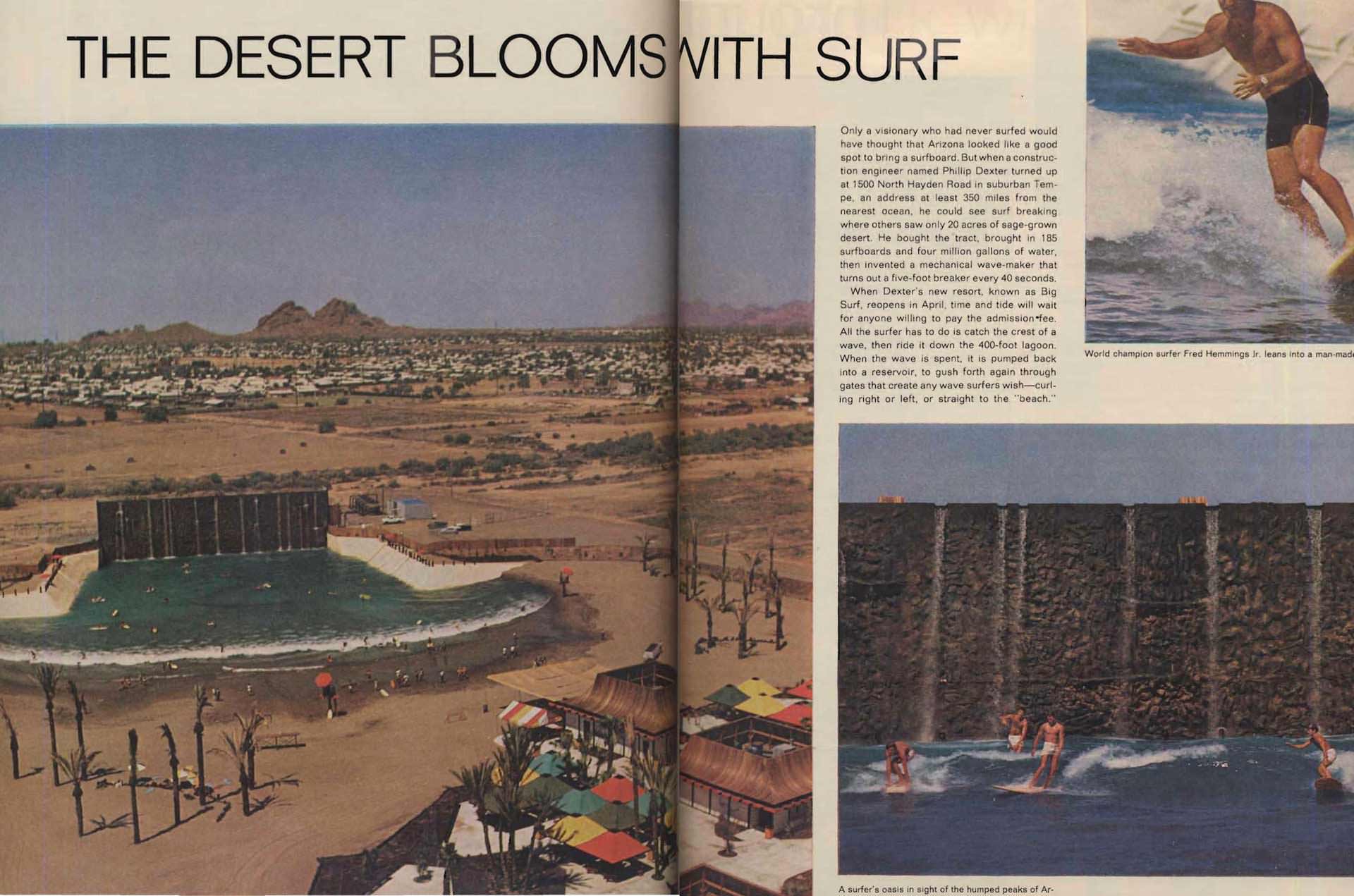

Big Surf

![]()

Communing with the mechanical wave

Text by Jason Griffiths

(Photo: bigsurffun.com)

-

![]()

Photos: bigsurffun.com

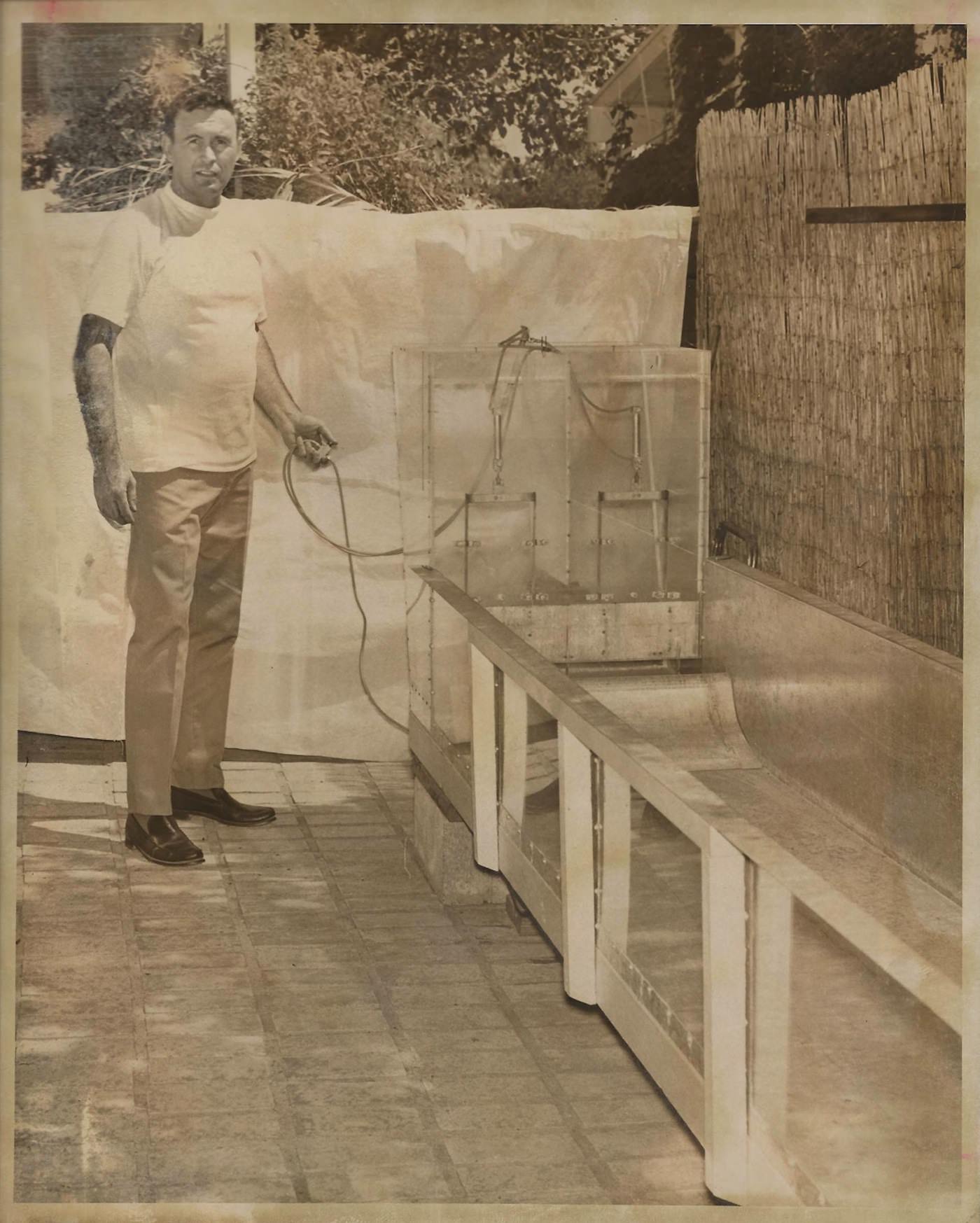

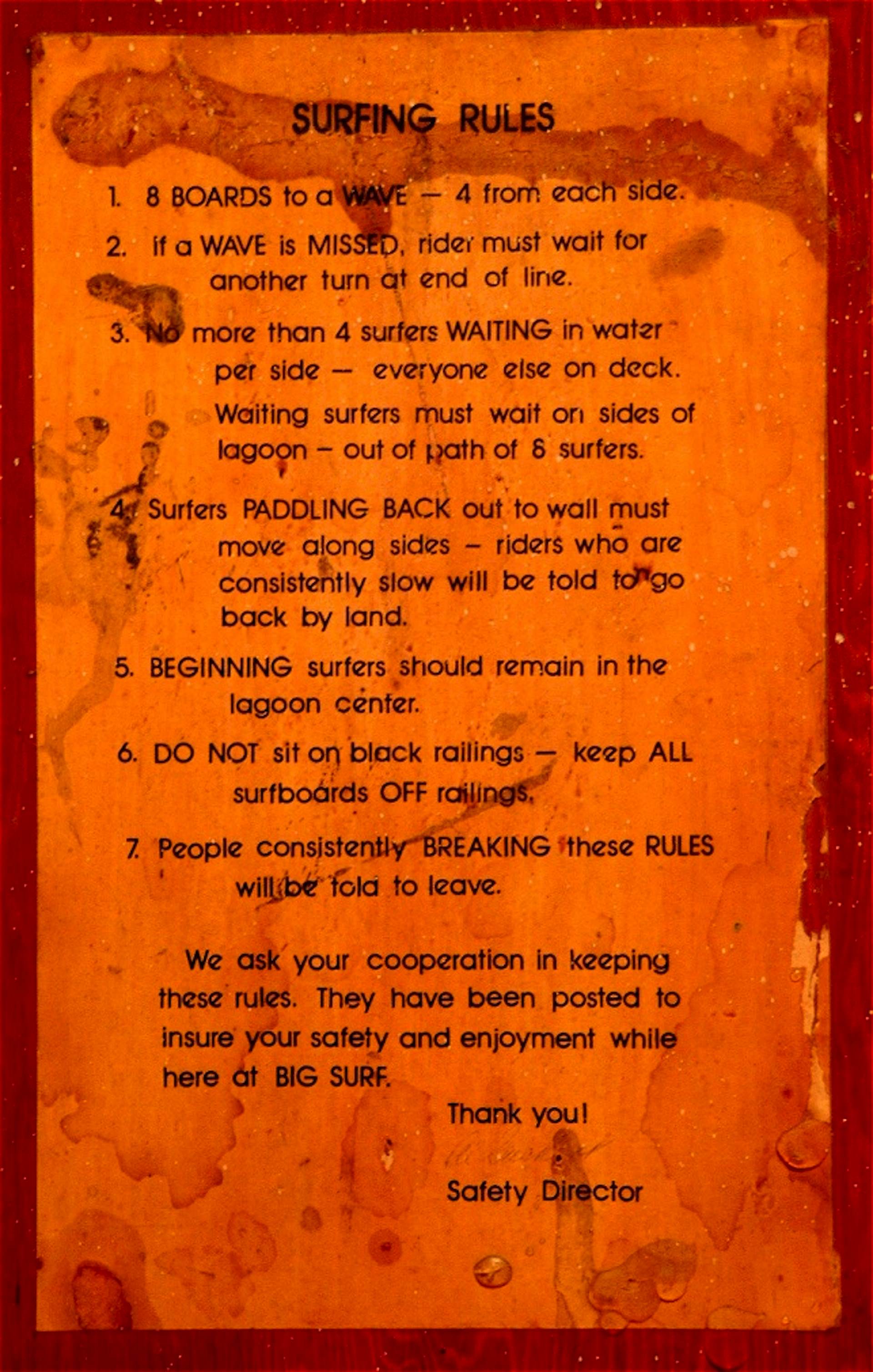

Arizona’s Big Surf is one of those projects that belong to the era of post-war boosterism and the unassailable self-confidence of an Arcadian dream. However, four years prior to its opening in 1969 it was just an idea — plus a 30x40 foot wave tank built by construction engineer Phil Dexter. Today we take artificial wave beaches more or less for granted, but at the time Dexter’s Big Surf ranked along with the best of the arid land utopias conjured out of a barren wilderness: Taliesin, Biltmore, Arcosanti. Under the wide aegis of the city of Phoenix, Big Surf adds its own form of Waikiki picturesque into the alchemy of surf culture, water engineering, and the notion of a truly endless summer.

![]()

-

![]()

Photos: bigsurffun.com

![]()

When Big Surf first opened it boasted a five-foot wave every minute, but over the years the waves have become smaller and less regular, perhaps synonymous with its diminishing status among many of today’s grander artificial wave systems. Of course, surfers can still appreciate its magnitude; the system’s pumps draw 50,000 gallons of water into giant cisterns within the wall, and when the wave comes it is triggered in booming flush as gates opens and the wave forms over a concrete baffle below the water line.

-

![]()

»Big Surf adds its own form of Waikiki picturesque into the alchemy of surf culture, water engineering, and the notion of a truly endless summer.«

(Photos courtesy bigsurffun.com)

-

Today Big Surf might not measure up to more powerful wave pools, but its history makes it an enduring piece of Americana. (Photo: Jason Griffiths)

-

![]()

An article on Big Surf graced the pages of this 1970 LIFE Magazine issue.

![]()

Engineer Phil Dexter with his 30x40-foot wave tank design in 1969. (Photo: bigsurffun.com)

![]()

(Image courtesy Big Surf Veterans Association)

-

Jason Griffiths is an architect and writer. He is Assistant Professor at the Herberger Institute, Arizona State University, Pheonix, Arizona. His work investigates the relationship between popular culture and architecture. Both his teaching and creative work explore digital fabrication techniques, investigating contemporary vernacular forms of building.

Jason has exhibited and published widely including in the AA Files, Architecture, JA, JAE and the Sunday Times. His book Manifest Destiny: A Guide to the Essential Indifference of American Suburban Housing was published in 2011 by AA Publications. It provides a visual anthropology of the North American suburbs and won the Deutsches Architekturmuseum (DAM) book award (Typology) at the Frankfurt Book Fair.

But the kick isn’t what it used to be. Veterans of Big Surf talk about “back in the day...when it had sand…a break to the left and the right….” with deep affection for its original mechanical nuances. This sounds similar to the typical talk of San Diego surfers — but this is affection for a machine! When you go to Big Surf you don’t become one with the infinite ocean, but instead commune with a mechanical wave beneath a giant painted sunset. Trips to Big Surf are an odd rite of passage for the modern surfer, a simulacra of the kind naturalism that surfers seek out. While today Big Surf’s artificial version of surf culture is no longer a technological novelty it will always be the first. It’s allure is a nostalgic one, the nostalgia for an original piece of faded Americana.

![]()

![]()

Beach volleyball, 1960s. (Photo above: bigsurffun.com, background photo: Jason Griffiths)

-

The Neverwas

Haul

If you’re going into the desert, you might as well do it in style. The Neverwas Haul, a vehicle-cum-Victorian house on wheels made from 75 percent recycled materials, certainly fits the bill on that score. Built in 2006 by Major Catastrophe, aka Shannon O’Hare and his art car factory Obtainium Works, is described as “an explorer’s club from some Victorian sci-fi.” Since 2006 it has made a regular yearly exploration to the one festival that all desert maniacs end up at: Burning Man in Nevada’s Black Rock Desert.

![]()

(Photo: S.N.Jacobson / LensCap, 2012)

![]()

'Neverwas Haul Video Project' by David Wilson.

-

Dubai Thriller

In the midst of the desert, the world’s largest fountain spews money 500 feet in the air

Text by Elvia Wilk

(Image: www.listofimages.com)

-

(Background photo: dubaidays-dubaidaisy.blogspot.de)

The collossal Burj Khalifa tower looms behind the fountain at 2,722 feet. (Photo: Elvia Wilk)

![]()

The fountain cost 218 million dollars to build. (Photo: friendskorner.com)

The world’s biggest shopping mall, the world’s tallest skyscraper, and the world’s largest “choreographed” fountain: the ultimate trifecta of monumental excess. “Monumental” and “excess” might be the best words to describe Dubai, the home of these three spectacular international landmarks, all positioned adjacent to each other in the city center. Their combination is an embodiment of the city’s explosive economic potential – and, of course, its potential for collapse.

The Dubai Fountain is a dynamic system of high-pressure jets and water-propelling robots. Situated in the 30-acre artificial Burj Khalifa Lake, the fountain can shoot 22,000 gallons of water up to 500 feet in the air, in coordination with the flashing and fading of 6,600 lights and 25 color projectors. This bombastic show moves in time to a soundtrack of contemporary pop music and traditional Arabic melodies – anything from Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” (a crowd favorite) to “Beba Yetu,” the theme tune of the videogame Civilization IV.

-

![]()

Dubai Fountain dances to Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” in 2010. (Video: Ivan Beato)

Water is a rapidly diminishing natural resource in the Gulf region. The Sheikh of Abu Dhabi recently referred to water as “the new oil.” And in the heart of the Arabian desert, water signifies wealth: the green, the growing and the organic are connected to privilege and excess. Here, an undeniable link exists between free-market capitalist spending, entertainment, leisure, and extravagant use of water.

In January 2013, the annual International Water Summit was held in Abu Dhabi – a meeting of world leaders, economists, and venture capitalists to address the increasingly pressing world water crisis. Within the same month, Yas Waterpark Abu Dhabi, which features the world’s biggest water slide, announced it was in the final stages of construction. It’s easy to proclaim the water crisis...but much harder to resist the bragging rights and tourist cash that come with water slides and dancing fountains.

![]()

(Photo: dubaidaisy.blogspot.de)

-

Extra Dry

On the RocksThe biggest telescope on earth sits high and dry in the Atacama Desert.

Hrrmmph (clear throat): “Starry, starry night….” A touch of the van Goghs in this time-lapse photograph of ALMA at night, the tracks of the stars evidencing the earth's rotation. (Photo: ESO/B. Tafreshi / twanight.org)

-

ALMA may be the mother of all telescopes, but it’s not the massively long tube you might imagine (sadly no need for a Mendlesohn-du-jour to house it in a suitable Einstein Tower-type visionary form).

Instead, this telescope — full name Atacama Large Millimetre Array — constructs images by combining radio waves beaming in from deep space, picked up on a series of antennas.

Resulting from an unusual transnational initiative between Europe, North America, East Asia and Chile, ALMA will eventually have 66 antennas — mostly 12 metres in diameter — combining to create images of the accuracy possible with a single 14-kilometre-wide one.

To minimize atmospheric interference, ALMA’s site is as high and dry as possible: 5,000 meters up on the Chajnantor Plateau, situated in the parched rain-shadow between the Chilean Coastal range and High Andes: the driest place on earth.

Each antenna can be moved between 150 metres and 16 kilometres, so this crowd of discs communes with the stars in slow-dance formation, their choreographed nodes forming a single vast virtual instrument. Tracking through infinite deep space, they pick up news of star-births and galaxy-sized gas clouds — perhaps discovering even that the universe is not desert(ed) after all….

![]()

![]()

-

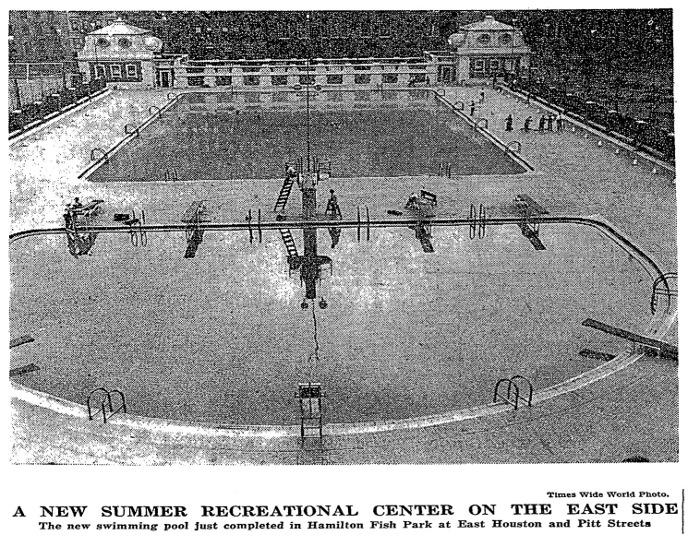

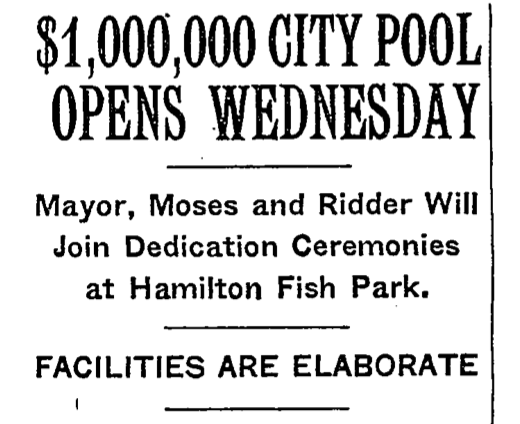

Pooling Around

Swimming through the history of New York City

Text by Jessica Bridger

(Image courtesy Rogers Marvel Architects)

-

There’s something to be said for a pool on a hot day. New York City is an urban desert in the summer: the winter winds that whip through the canyons of buildings cease, and heat descends. Many flee the city any chance they get, hoping to quickly forget the smell of reeking curbside garbage. Yet for others, leaving the city isn’t always an option. This has led to a growing recreation frenzy, and the public pools of NYC offer spectacular oases: not the least of which are eleven depression-era pools built under the oversight of infamous urban mastermind Robert Moses all in the summer of 1936.

There’s something to be said for a pool on a hot day. New York City is an urban desert in the summer: the winter winds that whip through the canyons of buildings cease, and heat descends. Subways become underground ovens. Many flee the city any chance they get, hoping to quickly forget the smell of reeking curbside garbage. Yet for others, leaving the city isn’t always an option. The dense city offers many options for recreation in the summer from shady parks to beaches. The public pools of NYC offer spectacular oases for cool fun: including eleven depression-era pools built under the oversight of infamous urban mastermind Robert Moses all in the summer of 1936. These pools were amoung the first civic structures to offer public swimming for all as a form of recreation.

(Image: Elliott Scott)

-

![]()

![]()

Photo: courtesy Library of Congress, Newspaper clippings: New York Times

The 11 pools were built by Robert Moses and mayor Fiorello LaGuardia. Moses was responsible for much of the public construction in NYC from the 1930s well into the 1960s. He wielded an immense amount of power and influence, and shaped the city in a totalizing way. Many remember him as a tyrannical pseudo-tragic figure, in large part because of his depiction in Robert Caro’s 1974 biography, The Power Broker, but still more benefit unknowingly from the things he brought into the world: from his vast expansion of the park system and planting of thousands of trees citywide to his design for the Triborough Bridge. Moses perceived that the people of NYC needed elements of public infrastructure like public parks and housing projects, and had the power to realize what he thought were appropriate responses to those needs. The pools, all built in underserved or economically challenged areas, brought relief from the punishing heat to many who had limited options for cooling off or recreation.

![]()

-

The NYC Parks Department still provides relief and escape today for the city via over 60 public pools. Their provision is largely the legacy of Robert Moses and the pools built in the the 1930s, funded by the federal Works Progress Administration (WPA). With street level temperatures that can rise well over 30° Celsius (90° F) and high humidity in the summer, the heat is like a viscous substance that immerses the city. The black asphalt streets radiate like an open oven, throwing heat up from the ground. Even the evenings offer little respite: high humidity and the urban heat island effect keep the city feeling warm, often too warm for comfort. For much of the population escaping to The Hamptons isn’t an option, and an air conditioner is an expensive “commodity.”

(Photo: Flickr, Modern_Carpentry)

-

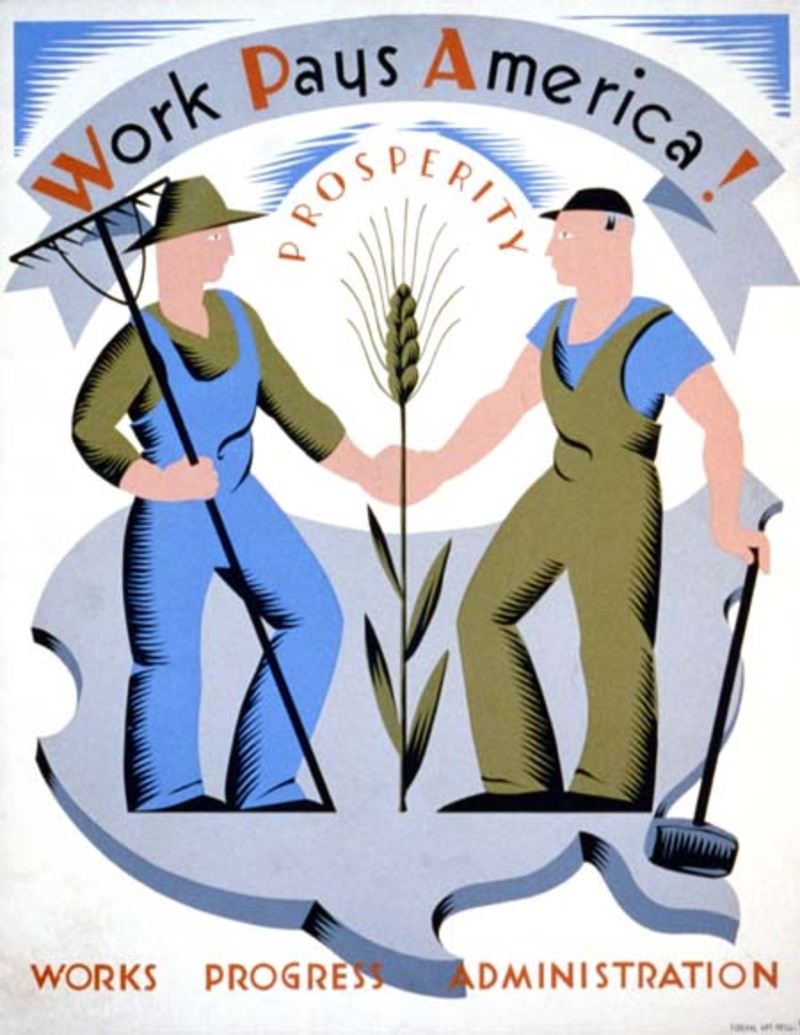

The Works Progress Administration (WPA) was a federal program put into place by depression-era US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt as part of the New Deal. The WPA employed 3 million people at its peak on a range of projects and programs throughout the United States from 1935 to 1943. Moses, a consummate politician was successful in securing major funds for WPA projects in New York City, including the 11 pools built in 1936.

(Black and white photographs: courtesy New York City Parks Department.

WPA propaganda posters: courtesy Library of Congress.)![]()

![]()

-

![]()

The design team of the WPA pools was led by architect Aymar Embury II and landscape architect Gilmore D. Clarke under the direction of Robert Moses. All were built using basic inexpensive construction materials including concrete, brick and steel. The layout of each pool complex was also the same, with a central bathhouse at the entrance on axis with the largest pool. Alongside a large pool for general use, each complex had a diving pool and wading pool. The design was standardized for easy repetition, adapted to each site and differentiated stylistically but with a modern vocabulary consistent throughout. This enabled the city to complete all the pools on time in the summer of 1936, and lowered overall costs. The city also provided recreational programs to encourage use of the pools, such as free swim instruction for all city residents. The NYC Department of Parks and Recreation still offers free swimming lessons at the 11 WPA pools and others throughout the city. This is especially important in underserved communities where learning to swim would otherwise be difficult.

(Photo: Rogers Marvel Architects; Poster: WPA advertising swim lessons in NYC, courtesy Library of Congress)

-

However, the story of the WPA pools is not all happy: time was not kind to Brooklyn’s McCarren Park Pool, which, like many of the WPA pools, fell into disrepair by the early 1980s. While the other ten WPA-era pools were restored in the mid-80s, McCarren’s planned renovation was stalled by residents fearing change would attract undesirable outsiders. Public interest in renewing the site was awoken in the 2000s, as gentrification brought a new demographic to the area, one that was lacking in major funds but was flush with creativity and social-political agency. Faced with limited options for informal summer recreation, McCarren Park was adopted as a venue for fun, including the empty pool basin with cracked blue paint slowly flaking off. Summer festivals, farmers’ markets and group sports started to occupy the empty complex after an initial influx of private cash from a music event ensured basic safety measures. It wasn’t long before corporate events managers and the city took notice and added more formal offerings to the park’s palette of offerings. The Bloomberg administration, custodians of New York City’s reformation in an era of gilded turbo-urbanity, eventually provided the funds to restore McCarren Park Pool as a functioning pool in 2012. Gentrification in this case assisted in restoring a public asset with a lineage from a seemingly more altruistic social era.

(Image: Flickr, joyruH7)

-

(Image: Rogers Marvel Architects)

McCarren Park Pool found new life in old forms in a renovation by Rogers Marvel Architects. The integrity of the original design was maintained throughout, and many historical elements were restored or repurposed. The three pools, large enough to allow 6,800 simultaneous swimmers in 1936, were modified to suit contemporary needs while maintaining most of the impressive capacity. The large central pool was made slightly smaller to accommodate accessibility measures and other modernizations, and along with the wading pool, both were restored to sparkling aqua condition. The diving pool – impossible in an America that has grown ever the more litigious, and cautious with its children over seven decades – was recast as a beach volleyball court. The line on opening day in 2012 and on subsequent days have often stretched around the chain link fence, and 2013 promises to be even hotter - and even busier.

-

The future of public infrastructure for swimming in the United States is finding new energy as civic activities and the general public start occupying waterfronts now vacated by industry and the cleaning of waterways becomes a priority. As these waterfronts change there seems to be growing interest in reclaiming natural waterways as swimming-places. New options for swimming – and summertime cooling – are opening up in American cities, beyond in-ground outdoor pools made from concrete. The Plus Pool project is one of the more innovative and ambitious new waterfront swimming ideas: a gigantic floating pool in the Hudson River using its water purified on site. Currently in a partially crowd-funded test-phase, the pool is eagerly anticipated as another public oasis to counteract the summertime urban desert.

![]()

(Image: Plus Pool)

-

Into the Dessert

![]()

Food + Architecture =

Farchitecture![]()

Architecture enthusiasts Natasha Case and Freya Estreller teamed up to create Coolhaus, a dessert company that began as a single ice cream truck in LA and has expanded into a whole fleet (plus a storefront in Culver City, CA). Their architectural ice cream sandwiches have deliciously punny flavors.

![]()

(Photo courtesy Coolhaus)

Flavors:

![]()

•Peter Cookies ’n Cream: Snickerdoodle, Cookies ’n Sweet Cream •Buck-Mint-ster Fuller: Chocolate Chip, Dirty Mint Chip •Mies Vanilla Rohe: Chocolate Chip, Tahitian Vanilla Bean •Bananas Foster: Double Chocolate Sea Salt, Bananas Foster •IM Pei-Nut Butter: Double Chocolate, Peanut Butter •Tea-Dao Ando: Vegan Ginger Molasses, Green Tea •Frank Behry: Snickerdoodle, Strawberry

![]()

![]()

![]()

-

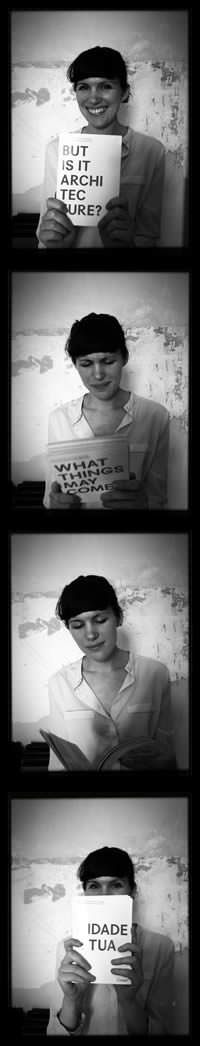

In the Photo Booth with…

Beatrice Galilee

“Close, Closer,” the third Lisbon Architecture Triennale, kicks off on September 15. Running for three months, it promises to deliver “an alternative reading of contemporary spatial practice,” with exhibitions, events, performances and debates across the city, responding to “a shifting economic and social climate.”

We invited its chief curator Beatrice Galilee into our photo booth to ask her about working in this context.Interview by Rob Wilson

![]()

-

Portugal has been one of the countries most affected by the Eurozone crisis. Has this context been a major factor on the thrust of your programming – apart from presumably on your funding?

Yes, definitely. We have all been taken by surprise at the extent of the fallout and the repercussions across this country have been huge. I think increasingly in this context, institutions like triennales and biennales are interested in taking on more civic roles and in exploring how to invest in the physical and cultural fabric of the city. Lisbon is certainly pushing that as much as possible.

The first way is through the New Publics programme which is specifically designed to address the specific context of practicing architecture and critiquing architectural practice in Lisbon, and additionally through our Crisis Buster grants, we gave 2,500 euros to ten projects, which including research into empty buildings in Lisbon, a political newspaper for public space and community initiatives in Lisbon.

-

How are you breathing new life or making relevant the biennale/triennale model, especially given this context?

I am working with a very strong and young curatorial team. We see the Close, Closer project as a space where critical discourse can be generated and new modes of thinking and practicing architecture can take place. We are exploring this by positioning each exhibition and project as a polar extreme of one form of contemporary architectural practice from agency to the intimate and speculative, to the dispersed and the pedagogical.

We are taking the Triennale into the city in quite a substantial way with our Associated Projects programme which features over 90 projects including morning runs, radio stations, communal clothes washes, restaurant tours and so on. Our Crisis Buster projects intend to support long-term civic initiative in Lisbon.

I have been really influenced by the previous biennales that I have been in involved with – the 2009 Shenzhen Hong Kong Bi-City Biennale and the 2011 Gwangju Design Biennale. In both events, the chief curators were working hard to push the genre of the event to explore the city, to work with an idea of a lasting legacy and also to use the moment to question the discipline itself.

-

“Close, Closer” is asking a lot of questions. To turn one of your own key questions around: what questions should architecture be asking today?

Yes, Close, Closer is about asking questions and not necessarily about giving the answers. We don’t see the exhibitions as ways of dispatching critical information but rather generating conversations and questions. In the context of Lisbon today, the question “What is architecture in a time of crisis?” is the one we’re hoping to answer.

-

Beatrice Galilee (*1982, London) is a London-based curator, writer and critic of contemporary architecture and design. She trained in architecture at Bath University, and in the history of architecture at the Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL.

She is the chief curator of the 2013 Lisbon Architecture Triennale, Close, Closer; the co-founder and director of The Gopher Hole, an exhibition and event space in London; architectural critic at Domus; and an associate lecturer at Central St Martins College of Art and Design.

She curated Hacked at the 2012 Milan Design Week, was senior curator at the 2011 Gwangju Design Biennale in Korea, and European curator of the 2009 Shenzhen Hong Kong Bi-City Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism.

She is a freelance contributor to several international exhibitions and publications of architecture and design and from 2006-2009 was architecture editor at Icon magazine.Close, Closer, the third Lisbon Architecture Triennale describes its aim as providing “an insight into the plurality of contemporary spatial practice.” For three months the curatorial team: Beatrice Galilee, chief curator, and curators Liam Young, Mariana Pestana and José Esparza Chong Cuy, will be examining the multiple possibilities of architectural output through critical and experimental exhibitions, events, performances and debates across the city.

The strands of programming include:

– Future Perfect, curated by Liam Young, looking at the imaginary urbanism, the landscapes and the narratives of a future city.

– The Real and Other Fictions, curated by Mariana Pestana, an exhibition of hyper-real architecture made of interdisciplinary spatial interventions at the scale of 1:1.

– New Publics, curated by José Esparza Chong Cuy, a series of acts in a city centre public square, addressing the concept of civic as opposed to public space.

– The Institute Effect, paying homage to the contemporary architectural institution – magazines, journals, websites, galleries, project spaces, archives, libraries and museums – and providing an embassy for their activity during the Triennale.

– Publications: Six special edition digital publications published over one year and designed by Zak Group, collectively designed to locate the theme of plurality in spatial practice into a broader global context.

– Crisis Buster Grants Programme, with grants awarded to support ten civic and social initiatives tackling specific issues identified in Lisbon, with potential for future continuation or replication, including funding for a political newspaper, supporting a community kitchen and garden and funding a new youth group.Close, Closer, the third Lisbon Triennale will run from 12 September to 15 December, 2013.

Since getting to know Lisbon through this project, what do you love the most about the city?

I know it’s famous, but the light really is incredible.

![]()

-

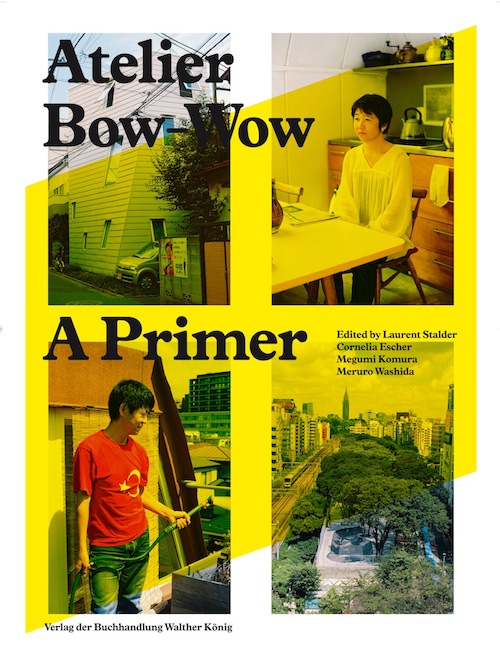

Atelier Bow-Wow: A Primer

Edited by Laurent Stalder, Cornelia Escher, Megumi Komura, Meruro Washida

Published by Verlag Walther König, 2013

Hardcover, 249 pages, 30.8 x 23.2 x 2.6 cm, English

ISBN-10: 3863353021

Ever since its foundation in 1992, Atelier Bow-Wow has been — through both its built work and research on contemporary Japanese urbanism — one of the most interesting and inspiring architectural offices in Japan. With a strictly chronological order, this book outlines each project or topic in one-to-four pages. The short but extremely precise texts are accompanied by beautiful drawings, diagrams and pictures. It presents a mixture of projects and ideas — from the design of Atelier Bow-Wow’s own studio space to the Guggenheim Lab, and from thoughts on flatness, windows, and pet architecture to manga, origami, and metabolism. Since all texts are written by the editors, the only thing missing is Atelier Bow-Wow’s own voice. A Primer remains an indirect description of their occupations – but it’s entertaining and educational, introducing you to “Oku,” “Iki-iki,” or “Sotei gai” on the fly. (fh)

![]()

![]()

-

ADD Metaphysics

Editor: Jenna Sutela

Text editor: Leah Whitman-Salkin

Published by Aalto University

117 Pages, Softcover, English

ISBN: 978-952-60-4954-0

This book of essays and homework-type assignments is a primer for designers to get meta. Editor Jenna Sutela brings together five premium metaphysicians in this publication by Aalto University Digital Design Laboratory (ADD). With texts by Jane Bennett, Vera Bühlmann, Graham Harman, Ines Weizman, and Andrew Witt, the compendium picks up on a central thread of contemporary philosophy: the so-called “object-oriented” turn. If philosophers are fixated on objects right now, designers always have been — it’s high time for some explicit crossover. Through ontological study of human-object relationships, ADD Metaphysics is the ultimate induction for designers and philosophers to enter the metaphysical zone between/beyond theory and praxis. As the book’s subtitle puts it: “Let the material not confine.” This is socially-relevant design education for today. (ew)

![]()

![]()

![]()

-

![]()

-

![]()

Issue No. 13:

August 29th, 2013![]()

Berlin.

Where do we go

from here?

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»What the map cuts up, the story cuts across.«

Michel de Certeau: Spatial Stories

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents