-

Magazine No. 13

Berlin

-

No. 13 - Berlin

-

page 02

Cover

Berlin

-

page 03

Editorial

Berlin

-

page 04 - 07

In & Out Of Berlin 1

Francesca Ferguson, Bostjan Vuga

-

page 08 - 20

360° View

In the Schinkel Pavilion with Nina Pohl

-

page 21 - 24

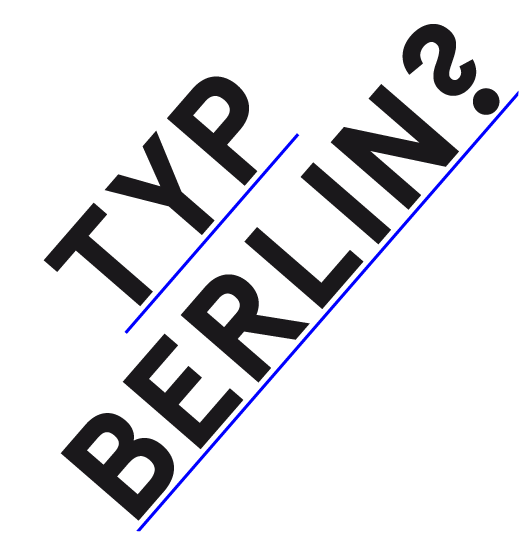

Typ Berlin?

In search of the ur-architecture of contemporary Berlin

-

page 25 - 27

In & Out of Berlin 2

Mark Lee, Konstantin Grcic

-

page 28 - 41

This Could Have Been Berlin

The visionary architecture of Engelbert Kremser

-

page 42 - 47

In the Photo Booth with...

Jürgen Mayer H.

-

page 48 - 56

A City Soft as Butter

Off to the fun fair with Simon Menges

-

page 57 - 60

In & Out of Berlin 3

Lukas Feireiss, Ellen Blumenstein, Karin Sander

-

page 61

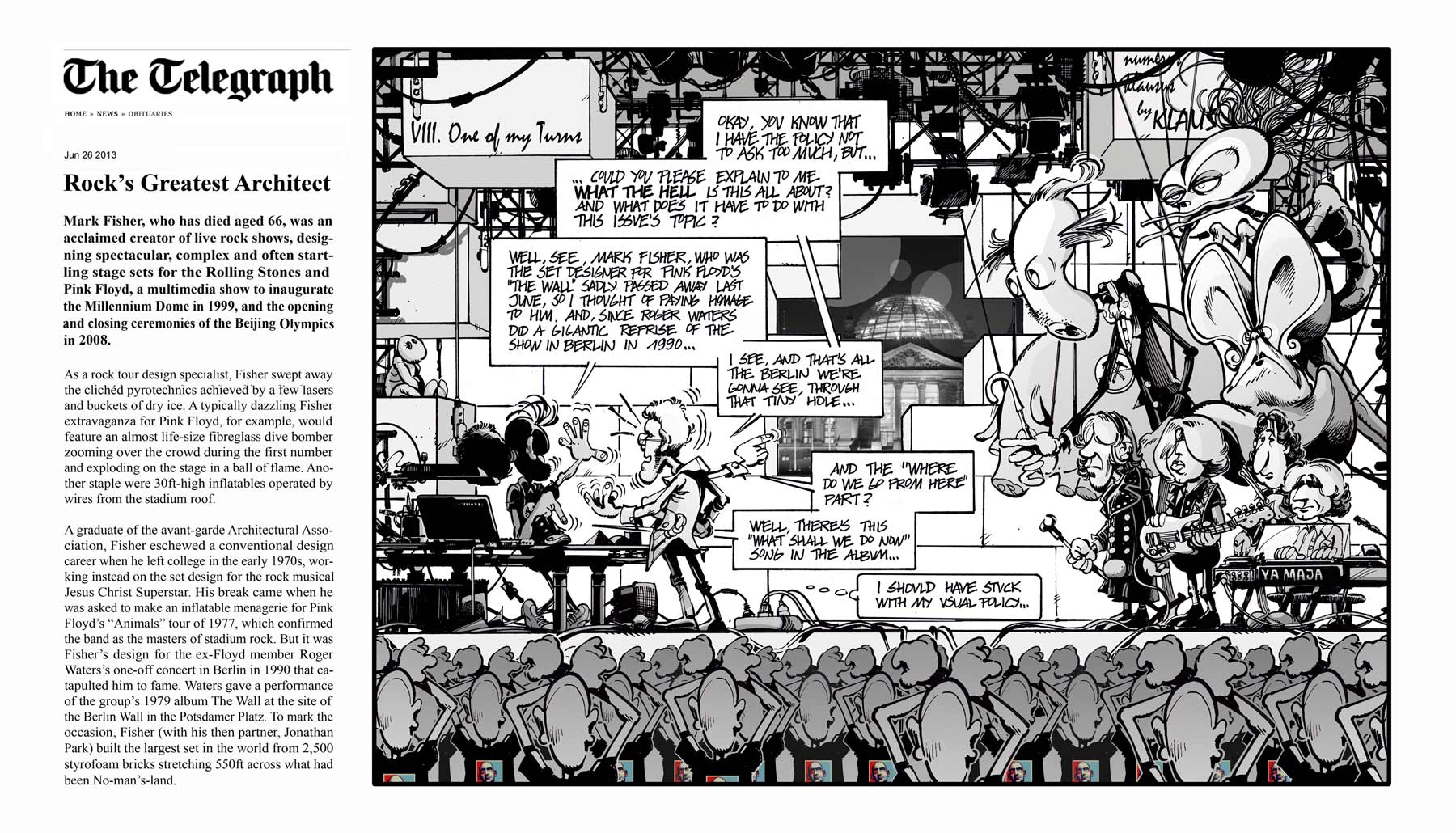

Klaustoon

VIII. One of my Turns

-

page 62

Next

Small Towns, Big Architecture

-

-

uncube’s editors are Elvia Wilk, Florian Heilmeyer, Jessica Bridger, and Rob Wilson. uncube is based in Berlin and is published by BauNetz, Germany's most-read online magazine covering architecture in a thoughtful way since 1996.

![]()

Welcome to Berlin, uncube's home turf.

From totalitarian regimes and republics to isolation and gentrification, Berlin has collected its fair share of identities, myths, and stereotypes — like any big city — but in this issue we get beyond what you might have already seen or heard about the most hyped capital of Europe. We present some of the people and places that haven’t been put through the Berlin branding-machine and talk to a selection of individuals who are helping create the 21st century incarnation of our city.

![]()

![]()

Cover Photo: Simon Menges

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

Francesca Ferguson

After first experiencing the city at the time of the fall of the Wall, Francesca Ferguson came back to live and work in Berlin, evolving her practice as a curator of architecture and urbanism, in particular initiating urban drift, an international network to develop urban strategies focused on void spaces and peripheral zones. Between 2006 and 2009 she was Director of the Swiss Architecture Museum (SAM) in Basel and is at present working on a forthcoming publication: Make_Shift City, which looks at critical spatial practice and 'austerity urbanism'.

![]()

-

Francesca Ferguson is a curator of architecture and urban design, consultant on journalistic and urban projects, and founder of urban drift. Based in Switzerland and Berlin, she is currently editor in chief of Make_Shift City, a publication on critical spatial practice and 'austerity urbanism', which will be published by Jovis Publishers in January 2014. A conversation series she has curated: Face to Face, between architects and their chosen counterparts, starts at the DAZ - German Architecture Centre, Berlin, on 23rd September 2013.

![]()

![]()

»I came to the city with ABC News on November tenth, 1989, to cover the fall of the Berlin Wall for television and I have stayed here ever since ABC set up a Berlin office. At that time, East Berlin was a good point from which to look towards Eastern Europe and investigate the profound changes taking place there.«

»My curatorial direction has been vastly determined by the rapid pace of change in Berlin’s urban fabric, and by the architecture and urban design strategies one could see evolving within the context of this city in particular. Ad-hoc urbanism coupled with bombastic and often flawed urban masterplans, symbolic spatial appropriations – such as that of the defunct Palast der Republik – alongside the demolition of architectural jewels such as the Ahornblatt restaurant, to make way for anodyne “investor-architecture”: all of this has fueled a discourse on critical spatial practice that still drives my work today. I have experienced no other city where one can create such useful links between disciplines, and I intend to continue to work with that – between the art scene, the design world and architecture/urbanism.«

»I think a crucial issue in Berlin is the sale of publicly-owned lands to the highest bidder – a policy pursued by the Senate for Finance and the state-owned property fund, the Liegenschaftsfonds. Civic engagement is now leading to a review of this very short-sighted approach to some of Berlin’s most precious spatial capital. There is also an urgent need to counterbalance the rampant property speculation here with affordable housing.«![]()

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

Bostjan Vuga

Slovenian architect Bostjan Vuga has been in and out of Berlin since before the Wall fell. Returning for two years in 2011, Vuga taught architecture at the Technische Universität as a guest professor. His Berlin stretches from 1980s ruins to contemporary new glass-and-steel architecture – guess which he finds more interesting?

![]()

-

Bostjan Vuga was guest professor in the Architecture and Design Innovation Program (ADIP) at TU Berlin from 2011 to 2013. He studied at the Faculty of Architecture in Ljubljana and the AA School of Architecture in London. He has lectured, taught, and been a critic at architectural schools, conferences, and symposiums in Slovenia and internationally, including the Berlage Institute in Rotterdam, the AA School of Architecture, the Bauhaus Kolleg in Dessau, the IAAC in Barcelona, at the ETH in Zurich, and at the Universität für Angewandte Kunst Wien and Academy of Visual Arts Vienna. As a visiting editor, he took part in two issues of AB Architectural Bulletin. He is a frequenter contributor of articles on architecture and urban planning to a wide range of both professional and general-interest publications.

![]()

![]()

»Long before I was a guest professor of architecture at TU Berlin, I spent two weeks in Berlin in 1988, attending the European Assembly of Students of Architecture (EASA). We all stayed in a big tent next to the Anhalter Bahnhof ruins. My impression of Berlin at that time was very much linked to the Wim Wenders movie Wings of Desire. We had a party in the ex-hotel Esplanade, an abandoned building at that time and the very same building where Nick Cave performs in the movie. And I was super astonished when I followed train tracks that ended in the Berlin Wall. I confess I found the interior of the now-demolished Palast der Republik in East Berlin much more interesting than an IBA housing development. Bonjour tristesse!«

»I have always wondered why, with so many creative people and so many empty places around, quite a lot of new construction going on, and so many well-trained architects around, there are so few examples of stimulating new architecture in this big city. It is so laid back, so austere and even boring. It’s more poor than sexy. Open the city for young creative architects! Dare to change the image of Berlin! As it stands, Berlin is not a test field for new architecture.«

»Being in and out of the city over the years, I’ve slowly learnt what I miss about Berlin. People, people, people: the mixture of people and ethnic groups. Also gigantic group karaoke sessions in Mauer Park, 3-day parties, and swimming the Spree River. Now I will also miss the 1960s generic, urban, German corporate smell of Ernst Reuter Platz. Not good for your soul, but good for your brain.«

![]()

-

360°

View

In the Schinkel Pavilion with Nina Pohl

Interview by Elvia Wilk(Photo: Chloé Richard)

-

The Schinkel Pavillon is a classical-looking glass-walled rotunda situated in a former palace garden just off Unter den Linden, with grand views of some of city’s key historical landmarks. It’s a typical piece of Berlin architecture in many ways – an amalgamation of historical styles and materials and functions. Built in 1969 by the modernist DDR architect Richard Paulick, the pavilion’s façade contains terracotta elements salvaged from the nearby Bauakademie – constructed in 1836 by the renowned architect Karl-Friedrich Schinkel, but later bombed in 1945 and demolished in 1962.

Dressed in cannibalized Prussian décor and an iconic Prussian name, the pavilion was once a venue for GDR cocktail parties before the Wall came down. Now it is a public contemporary art space hosting exhibitions and events, but like many buildings in the city it’s about to get crowded in by one of the countless private development schemes jostling for prime real estate acreage. We talked to Nina Pohl, curator of the Schinkel Pavillon since 2007, about the history of the building, its life as an arts space, and how its increasingly claustrophobic urban situation is indicative of Berlin’s development as a whole.

-

![]()

Deafening construction sounds are a constant reminder that the Schinkel Pavillon will soon be blocked off by a new townhouse development. (Photo: Chloé Richard)

-

Elvia Wilk: How did you end up in Berlin?

Nina Pohl: I came to Berlin from Dusseldorf in 2006. At that time everyone in the Rhineland felt we should move to Berlin because it was dying where we were. I was in the second wave of people leaving. It seems like nobody lives in Dusseldorf or Cologne anymore.

At what point did you get in touch with entrepreneur Stephan Landwehr, who initiated using the Schinkel Pavillon as a space to show art?

He asked me to join the project six or seven years ago, and at the beginning we worked on it together. Then he stopped being involved, as he had too much work with the restaurants he owns — Pauly Saal and Grill Royal.

When Landwehr acquired the space, he was particularly interested in the chance to display art in a windowed open room with natural light. Was this one of the things that attracted you as well?

It’s hard to explain. There’s something mystical about the pavilion. The first time I visited was at night, when you can see all the city lights and the skyline. I was impressed by the mood of the space; it has something very particular, very special, almost overwhelming. I didn’t get that feeling from other places in Berlin.

![]()

In her 2012 installation “Hallelujah,” artist Isa Genzken played off the pavilion’s views of the city skyline, with visual puns like an image of the Television Tower and a director’s chair facing the vista. (Photo: courtesy Galerie Buchholz, Berlin)

-

Dirk Bell, “LI´ve is LI´ve,” 2009. (Photo courtesy Schinkel Pavillon)

-

To me, the mystical quality you mention is partly due to its multi-layered history. In some ways it’s the epitome of the “Berlin building,” an amalgamation of remnants from various historical moments.

It’s totally Berlin! It’s hard to think of a building that compares. The Schinkel Pavillon also belongs to the Kronprinzenpalais (Crown Prince Palace) nearby on Unter den Linden – we’re in its garden. It was originally a Stadthaus (city hall) built in the seventeenth century, and in the 1920s it housed the first museum of contemporary art in the world – it was actually the template for MoMA. The curator of the Nationalgalerie, Ludwig Justi, was the first curator to make studio visits to meet contemporary artists, gathering their works and curating them in the museum. Justi mostly showed German Expressionism, which was later designated as Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) and seized by the Nazis in the thirties. Then the museum was closed, and in 1945 the building was bombed and totally destroyed. Both the Kronprinzenpalais and the pavilion were rebuilt in 1969 by Richard Paulick. He was a very important architect during the DDR, and these two buildings were significant during that time. GDR leader Eric Honecker had his cocktail parties here.

![]()

When he built the Schinkel Pavillon in 1969, architect Richard Paulick incorporated terracotta reliefs from Schinkel’s original Bauakademie in its interior and exterior. (Photo: Chloé Richard)

-

So you’re continuing in that tradition?

Absolutely!

And your programming reflects the history of the Kronprinzenpalais, which was not only intended as a place for showing current art but for gathering people together.

Right, that’s why I made the Schinkel Pavillon a registered Kunstverein, part of a German system in which the public can become members and pay an annual fee to support us.

![]()

(Photo: Chloé Richard)

-

Would you consider using the pavilion as a commercial gallery space?

I’m not interested. I like to use it as a melting pot, as a platform for social activities, and I don’t want to have a commercial enterprise. I invite the artists I like. It’s very spontaneous. This is an advantage compared to big institutions, because we can react very quickly from one day to another, making a lively program. And of course I like to invite artists who react strongly to the space.

Performances in particular take on a special quality here.

It’s very important to hold live events rather than just putting a nice sculpture in the middle of the room. You have to have a dialogue with the audience, and a performance is the best way to communicate with the city.

»It’s really a pity that every free space in Berlin is being covered with new development.«

For instance, at Cyprien Gaillard’s 2012 show, What it does to your City, he placed classical sculpture in the pavillon, but there was also a performance outside the building – drawing the outside world in.

This was a work that directly addressed the pavilion’s urban environment.

It was a show about how the city is dealing with architecture – destroying or shutting down free places. For example, what is happening here with Schinkel’s Friedrichswerder Church, which is directly visible from the Schinkel Pavillon. Construction is beginning right now on a group of townhouses directly between here and the church, right up against it. It’s a disastrous architecture, this pseudo-nineteenth century building, going at 10,000 euros per square meter to rich Russian expats ... it’s really a pity that every free space in Berlin is being covered with new development.

-

![]()

Sylvie Fleury, “Hypnotic Poison,” 2007. (Photo courtesy Schinkel Pavillon)

Saâdane Afif, “The Fairytale Recordings,” performance, 2011. (Photo: Jan Windszus, courtesy Mehdi Chouakri, Berlin / RaebervonStenglin, Zürich)

»I don’t want to have a commercial enterprise. I invite the artists I like.«

-

![]()

In conjunction with his 2012 exhibition “What it Does to Your City,” Cyprien Gaillard staged a performance in a construction lot adjacent to the Schinkel Pavillon: a choreography of shovel-excavators accompanied by xylophone music.

(Photo: Linus Dessecker , © Cyprien Gaillard , courtesy Sprüth Magers Berlin, London)

(Video: One-minute excerpt from Gaillard’s twenty-minute performance, “What It Does To Your City,” during Berlin Art Week, 2012.)

-

But the area has always been folding back on itself like this, referencing the past — Schinkel’s Church, for instance, was one of Berlin’s first Neo-Gothic buildings; it was already an appropriation of a historical style.

Yes, but what’s strange is that today the area’s history is being used to justify the new construction. At the time when the Friedrichswerder Church was originally built, there were townhouses in the exact area where they’re being built now. Because it’s deemed authentic, it’s possible to justify building townhouses there again. But it’s ridiculous to put that development so near to the church and to destroy the whole view!

You mean plopping this massive high-end apartment block between the church and the pavilion cuts off any visual understanding of historical connections between the two?

At the moment there are still views from every angle of the pavilion – the city itself enters the space. In this little building, there is so much reflection of history – it’s a potpourri of the past. The terracotta reliefs dotting the outside and inside of the Schinkel Pavillon are from Schinkel’s Bauakademie – they are melded into the surface of an East German reconstruction. It’s a collage of art and architecture.

![]()

Jeremy Shaw, “Variation FQ,” 2013. (Photo: Nick Ash, courtesy Schinkel Pavillon)

-

Nina Pohl is a Berlin-based artist represented by Sprüth Magers Gallery.

![]()

(Photo: Chloé Richard)

»In this little building, there is so much reflection of history«

You’re also an artist. How does your work respond to the experience of working here?

As an artist you’re always alone in your studio, and often you don’t have much conversation with the outside world. But if you are both an artist and curator, you have to see a lot of art, do studio visits, and create strong dialog with other artists. This creates a very rich life for me.

Sounds like you’re staying in Berlin.

Will I stay here? Of course. I’d never drop the pavilion.

![]()

-

![]()

In search of the ur-architecture of contemporary Berlin.

Text: Florian Heilmeyer and Rob Wilson

Rachel, Brandenburg, 2012 - 2013, by Brandlhuber + Architects (Photo: Erica Overmeer)

-

![]()

Rachel is a space by Brandlhuber + Architects in Brandenburg with (as yet) no defined function. 2012-2013. (Photo: Erica Overmeer)When Le Corbusier’s Unite d’Habitation in Berlin was completed in 1958, he was so unhappy with the compromises exacted by local building regulations, that he insisted the building must henceforth be called “Typ Berlin” — as in Berlin-type boring. Municipal red tape has been diluting exciting architecture in the city ever since, but there are some exceptions. uncube found three local projects that reflect the specific conditions of the city today.

History Cast in Concrete

“This building is situated in Krampnitz, a former military base about five kilometers from Berlin in the state of Brandenburg. Despite its distance, one could say it is actually influenced by some typical Berlin things. For instance, it is the result of colliding heterogenous layers of history: we have used the remains of the building that once occupied the place — a small assembly hall for the workers of a little factory dating back to the GDR – but we have cast them in concrete. This idea is loosely based on the work of the artist Rachel Whiteread, which is where the building gets its name.

Rachel is rough enough to serve different uses. This versatility also relates it to the strategies of spatial adaptation that have been so typical of the subcultures of post-Wall Berlin. Others have to judge how this building relates to contemporary Berlin architecture – but to us Berlin is definitely present in Rachel.”

-

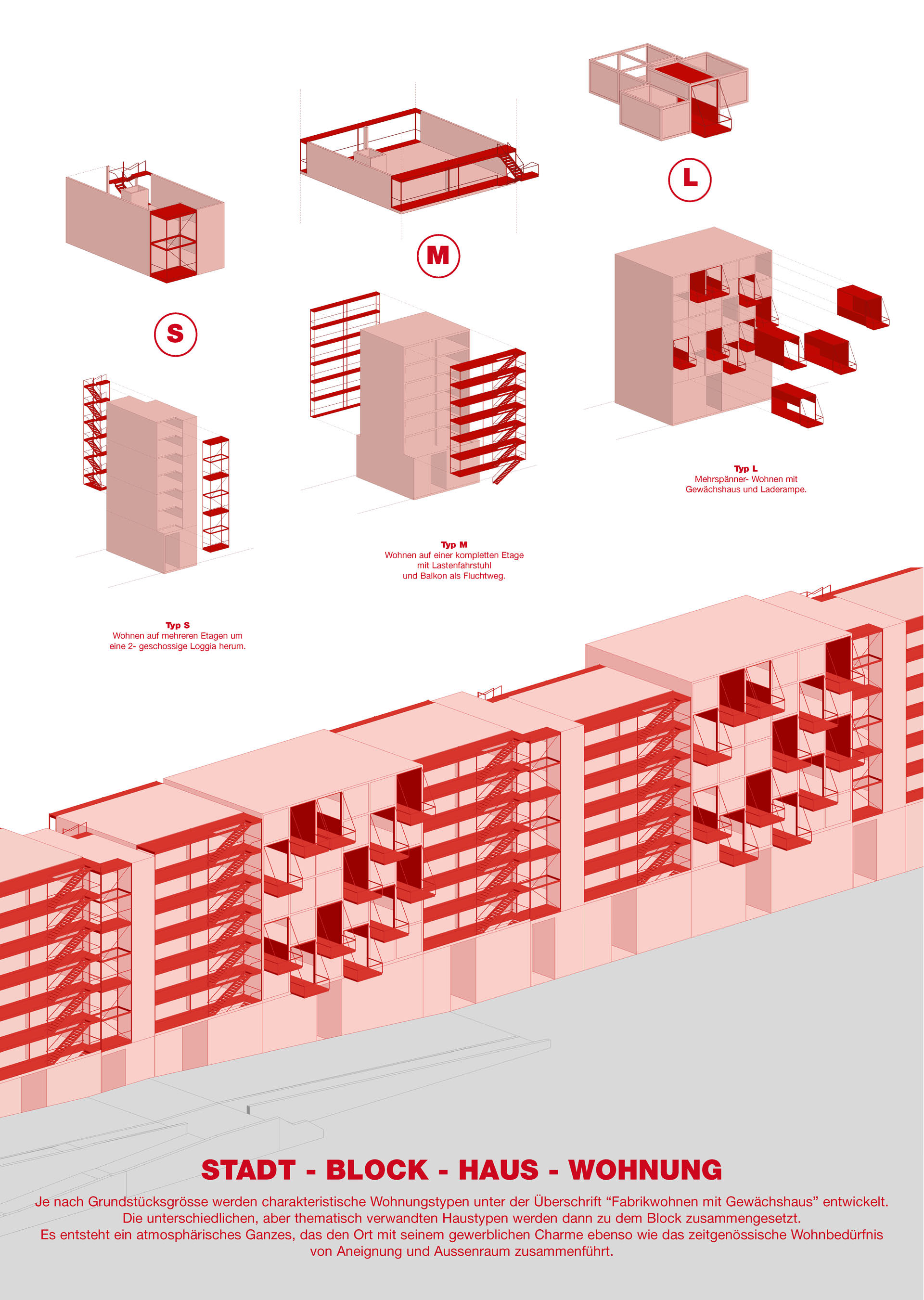

How to Build a Loft Anew

“This project is being constructed right next to a former train depot, which is also currently being reconverted as part of the new Gleisdreieck Park scheme. Am Lokdepot is a medium-sized housing scheme, but we aren’t interested in the kind of isolated residential quarters that are currently being erected throughout Berlin. We didn’t want to start from scratch, but to continue from what is already there. That’s because we want to reinforce or contribute to Berlin’s heterogeneity, which we see as one of the city’s most vital characteristics. Since the fall of the Wall, Berlin has been a do-it-yourself city – a city of appropriation, redevelopment, and temporary use. With Lokdepot we are trying to develop a strategy for new housing that is appropriate to these specific conditions.

The abandoned tracks and the two old locomotive halls are our main aesthetic reference points. We are entering into dialogue with the past on several levels: with the materials – cobblestoned paths, colored concrete, lacquered rustproofed steel, recycled bricks – and with spatial formats: the apartments offer open floorplans that can be individualized. It’s meant to be a reinterpretation of loft living – but in a new building.”

![]()

![]()

Robertneun Architects: Am Lokdepot, Gleisdreieck, Berlin, 2011 – 2015. Under construction and isometric. (Images: Robertneun Architects)

-

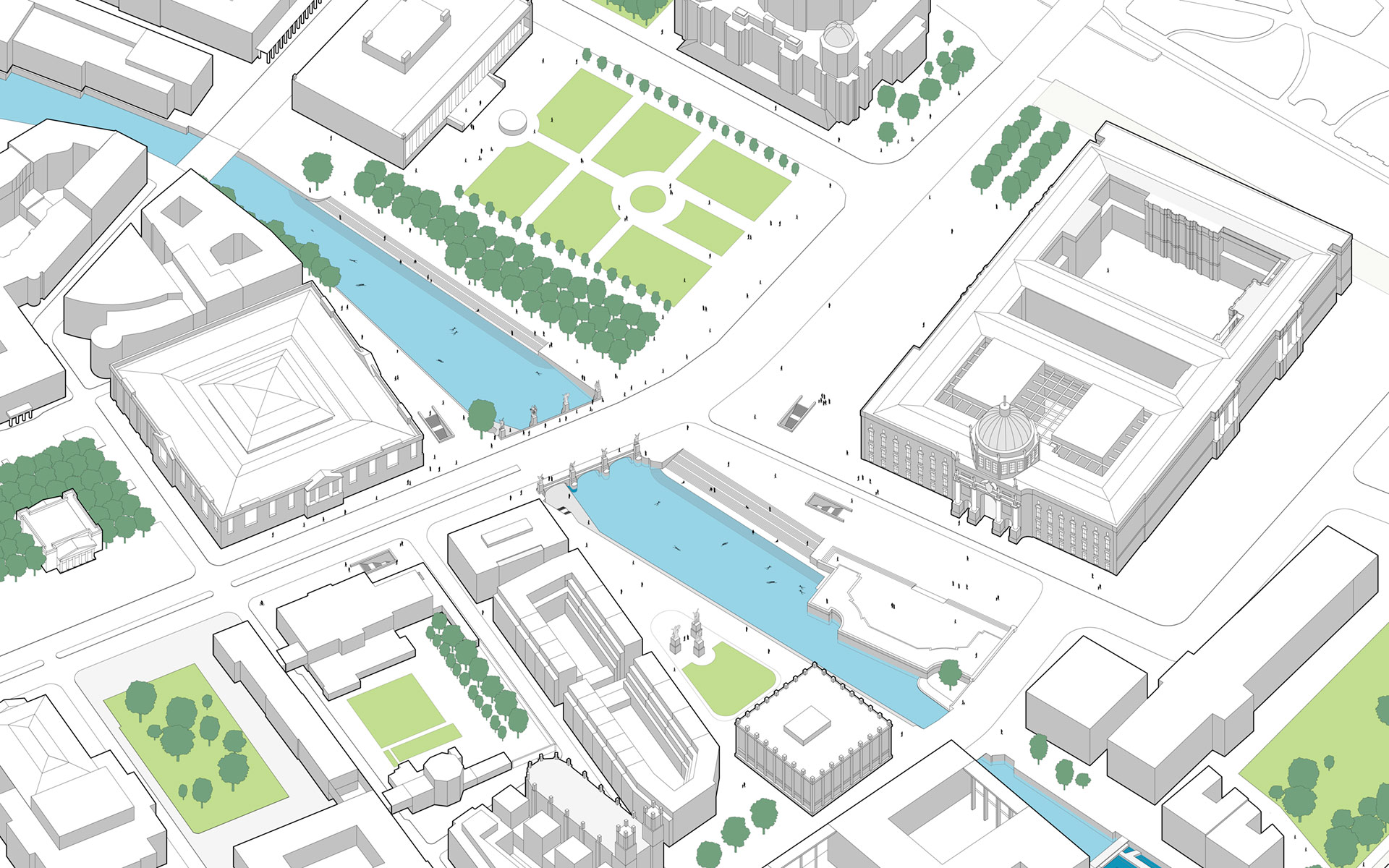

Central Pool

“We want to turn a part of the Spree River, which is already clear of river traffic, into a public bath – a Flussbad. Many other cities have a public bath, but in contrast to many this one would be as central as possible, literally in the heart of the city, which is otherwise mostly devoted to tourism. Our Flussbad would be 740 meters long and create an immense attraction for inhabitants and visitors of the city alike. Back in 1998, most people regarded this idea as pure lunacy. But when the project received the Holcim Award for Sustainable Construction in 2012 there were glimmers of vague interest from the city. Maybe Berlin is finally ready for an urban transformation like this: huge in size but relatively pragmatic in terms of re-using an existing situation. The use of the river has always changed throughout history – it’s been used for fishing, defense, energy, transport – and our contemporary interpretation could indeed become something that is now typical of Berlin’s current needs. By the way, you can all help turn this project into reality by joining our supporters club: follow this link! ”

![]()

Flussbad, a proposal for the Spree River, Museum Island, Berlin, 1998 – 2020, by realities:united. Rendering and site axonometric. (Images: realities-united)

![]()

-

Mark Lee is a founder and Principal of Johnston Marklee, an architecture practice which collaborates with advanced research teams composed of innovative thinkers and designers from professional and academic disciplines. From a knowledge of both architectural history and contemporary discourse and construction practices, Lee directs the practice’s design teams in critical research combined with efficiency and precision in production.

Lee has written and lectured widely on his research regarding culture specific landscapes and new strategies in material form and technology, and has been invited as a visiting critic at numerous institutions around the world, including Harvard University, Princeton University, Cornell University, University of Michigan, UCLA, UIC, T.U. Berlin, ETH Zurich, Rice University, and SCI-Arc.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Mark Lee

An American in Berlin, Mark Lee found the city – especially the dramatic sky and generous outdoor cafés – a very pleasant place to spend two years as a guest professor in architecture at the Technische Universität. But more than the environment, Mark says the city’s unique creative environment reminded him of his hometown Los Angeles.

![]()

»I loved being in Berlin. Other than Shanghai, Berlin is the only city I know that is truly a palimpsest of the twentieth century. Not that previous centuries didn’t leave their mark, but one really experiences the scars of the last hundred years imprinted in the city: every major world event, catastrophe, superpower tensions; all have left traces in Berlin. It feels like being at the crossroads of the world when in Berlin.«

»The creative energy in Berlin is indisputable. The “poor but sexy” image still works, but it is a moniker that has an expiry date attached to it. My hometown, Los Angeles, another city famous for its creative energy, was once just known as a place where art and things were made to be sold elsewhere — in New York or London. But over time LA has evolved into a city where not only things are made, but transactions are made as well. In the same way I feel Berlin’s specific conditions and infrastructure that nurture its creativity – whether the affordability or the open mindset – also need to grow into something else. A creative city does not stay like Peter Pan forever. I wish it were as much as a financial capital as it is a creative capital.«

![]()

-

![]()

![]()

Konstantin Grcic

Konstantin Grcic is a part-time lover of Berlin: His base for most of the month is Munich, but he has chosen Berlin as his alternative occasional home, one in high style as you’d expect from this internationally known industrial designer: an Alvar Aalto-designed apartment in the Hansaviertel.

![]()

-

Konstantin Grcic is an industrial designer. Born in Munich in 1965, he became a cabinetmaker before going to London to study Design at the Royal College of Art. In 1991 he started his own studio in Munich where he has been based ever since. Since 2010 he has also had a studio/apartment in Berlin.

![]()

![]()

»I don’t plan to move to Berlin permanently. I like the differences between it and Munich. The periodic change is good for my head. I spend about 10 days a month in Berlin – not only because of my girlfriend, but also because I can concentrate on work here. It sounds absurd, doesn’t it? Most people don’t come here to concentrate on work. But there are some days when I hardly leave my apartment. I look out from the sixth floor onto the Tiergarten, and beyond that, the Television Tower. My apartment is like a throne. I go jogging through the government quarter and feel like I’m in the midst of things.«

»The Hansaviertel has always fascinated me. For me it’s emblematic of Berlin, even if it is quite atypical. It’s a utopia, an island. Although it is already 60 years old, its architecture remains a symbol of free, open, and future-oriented thinking. There is something very optimistic about it.«

»For me the greatest surprise here is to discover the areas in Berlin that lie between the better-known neighborhoods. When you are no longer a tourist, then your radius expands. You ride your bike and slowly the pieces come together. Then you realize how different the neighborhoods are, all the green, the canals and the parks, the beautiful plazas – I never would have expected to find such beauty in this city.«

![]()

-

![]()

The visionary architecture of Engelbert Kremser

Text: Florian Heilmeyer

This small pavilion built in 1985 in the south of Berlin remains Engelbert Kremser’s most famous building. Small in size, it demonstrates the possibilities of freely forming concrete buildings from the “earth architecture” technique he invented. The building is ageing well, as seen in this picture taken in August 2013. (Photo: Schirin Torabi)

-

The architect and painter Engelbert Kremser left Berlin in 1990. Prior to that, he had been trying for 30 years to come to terms with Berlin’s building sector, with its lack of imagination and fear of the new. Only a few of his strange yet fascinating designs ever made it to reality, but his spirited collages from 1969 make us wonder whether an utterly different Berlin might have been possible.

Engelbert Kremser sits in a beautiful little house in Potsdam, surrounded mostly by things he has made himself, slotted-together furniture whose odd forms recall Art Nouveau. Each piece of furniture can be cut from a standard sheet of plywood from the DIY store. The shapes are laid out on the sheet in such a way that no wood is wasted. They are then cut out, fitted together and painted white. Anyone could do this themselves. Has he tried to have them mass-produced? “No, no”, says Kremser. “I’ve never had a good experience working with manufacturers”. Kremser just makes things for himself; he has no more expectations from industrial manufacture, neither for furniture nor buildings.

![]()

Engelbert Kremser in August 2013, sitting on his terrace, which he constructed himself, on one of the chairs he designed. (Photo: Torsten Seidel)

-

![]()

![]()

Kremser bought his small house in Potsdam in 1990. Since then he has made it his own, building a concrete portal in front of it, adding an organic-style terrace, and some mosaïcs. He furnished it with organically formed shelves, closets, tables, and chairs, all designed and built by himself. The chandelier in this photo is also – as you might have guessed – Kremser’s own work. (Photos: Torsten Seidel)

-

From Racibórz to Berlin

Engelbert Kremser was born in 1938 in Racibórz. When only ten years old, Kremser discovered painting when he met the painter Bolesław Juszczęć: “He showed me all the techniques, he wanted to make me into a painter. But I chose architecture, which seemed to me a good connection. Architecture initially emerges in your head, then it somehow must be put on paper. You must be able to express yourself before you start to build.”

Kremser′s father brought the family to Hanover in 1957 where Kremser began studying architecture in 1959. “In Racibórz, we were Germans. But in Hanover, all of a sudden, we were regarded as Poles. It was a terrible time, the people were poor and rude. As migrants, we were insulted everwhere, even at college.” Later when he visited an open, pre-Wall Berlin together with fellow students, he fell in love with the city immediately: “Berlin was so big and diverse. People came from all over; where someone came from wasn’t important at all. Here, I was no longer a migrant; suddenly, I was a human being.” They visited the International Building Exhibition in Hansaviertel. “We saw the buildings by Niemeyer, Aalto, Baumgarten, and Frei Otto. There was nothing like that in Hanover. You could say I moved to Berlin in 1961 for two reasons: for the architecture and to be a human.”

![]()

(Photo: Torsten Seidel)

-

![]()

Kremser developed an organic way of forming architecture, where concrete is poured directly onto sculpted earth. The concrete can be formed by hand or with simple tools, much like a sculptor would work. Afterwards the earth is dug away from the hardened form. His first building with this method, which had never been tried before, was a garage with a terrace – which he had to demolish again and again before arriving at a suitable outcome. (Photo: E. Kremser)

Erdarchitektur

In Berlin, Kremser devoted himself to organic architecture. “In college, we were allowed to “scharoun-ize”, “corbu-ize”, and “aalto-ize”, as they said. Of course there were many who still kept to Bauhaus-style boxes. But not me.” At first, he sees the “boxes” as just another architectural style, but later they symbolized the enemy for Kremser. “The problem is that most of these boxes are not able to create any relationship with their surroundings – they simply ignore it. They are just boxes.” He wants to build differently: soft and dynamically, creating fluid connections and smooth transitions. Contacts with Frei Otto, Stephan Polónyi and Hans Scharoun, in whose office he worked for two months on the Berliner Philharmonie, confirmed his chosen direction.

-

In a book on shell structures, he discovered the Albuquerque Civic Auditorium from 1955, where an existing mound of earth was reshaped to simply pour a large concrete slab over it. Foundations and supports were put under the slab, then the earth was dug away resulting in a domed hall 66 metres in diameter. “Using the earth itself as formwork – I found that idea so fascinating! Only the slab’s smooth shape bothered me. I wanted to stomp around on it, destroying its perfect form to give it some character.” That’s how Kremser came up with the idea he has pursued ever since, which he gave the name “Erdarchitektur” or Earth architecture.

From earth and plaster, he made 1:50 scale models to test his ideas a little. He built a garage for a doctor, using a mound of earth to model the pourable concrete by hand. “A disaster! First, everything went wrong; I had no experience and no one had ever done something like this before. The concrete kept sliding down and I had to demolish it again and again. But slowly I learned how wonderfully you can model concrete by hand – what viscosity it needs.”

»You could say I moved to Berlin in 1961 for two reasons: for the architecture and to be a human.«

For children and plants only

A commission followed: a playground with a playhouse. In Märkisches Viertel of all places: a fig leaf for one of the cheapest examples of postwar modernism in West Berlin. Kremser worked for eight years on the building, which merges with the playground and the landscape. It was pretty obvious from the very beginning that to realize this building was an experiment. But at some point during the eight years, his client started to lose faith in Kremser, the sculptor, who worked spontaneously and mainly with his hands on-site. Then as his design couldn’t be verified using conventional methods, the structural engineer withheld his approval. Had Kremser not found prominent advocates, such as Arup Engineers, who wanted to see the experiment completed, the building would probably never have been finished.

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

Construction of the “Café am See” (1983-85). This pavilion is part of a new park, called Britzer Garten. Kremser’s construction technique had progressed since his first attempts. Today it is seen as an idiosyncratic and impressive structure, merging with the landscape around it. (Photos: E. Kremser)

Disputes with the public authorities continued to plague Kremser. For the park pavilion that Kremser built in 1985 in Berlin-Britz, he had to overcome a lot of opposition. With so few commissions, Kremser continued developing his ideas for earth architecture mainly on paper. But he was convinced that his construction method could also be used to build high-rise buildings at no additional cost: He demonstrated this in 1989 with an office building for Berlin’s Pflanzenschutzamt (Plant protection office) where the floor slabs were cast individually in earth formwork and then lifted into place. It was to be the last building he realized in Berlin.

“I wanted to build big housing schemes. But my architecture was perceived as suitable for children and plants only,” says Kremser. “No one could imagine it for adults.” Even Scharoun’s masterpiece, the Philharmonie, was contested in Berlin for years. Berlin’s Senate lacked the courage and private investors were virtually non-existent in West Berlin. As the Wall fell and Berlin was overwhelmed by the frenzy of reunification, a formal architecture was prescribed for the city that excluded Kremser’s earth architecture from the outset. “I didn’t need to participate in any more competitions. I just needed to look at the jury, then I already knew that my ideas wouldn’t stand a chance.”

-

»To build something yourself, to make it with your own hands – that’s the greatest joy.«

“Cafe am See” in the Britzer Garten, Berlin. With its terraces and arcades, the building connects to its context in many ways. (Photo: E. Kremser)

-

Aggravating Places

The few buildings Kremser has realized aren’t that imposing as structures. It’s rather their concept, their richness of ideas, and the courage to try to find a completely different way to think about architecture and city that’s impressive. What might have been possible with earth architecture is best demonstrated by 14 photomontages that Kremser made in 1969. He photographed the buildings that aggravated him the most on various squares in West Berlin, and then cut them out from the photographs and replaced them with his own designs. He points out that these collages are not at all capricious: “These are studies made to correct scale, with the thinking behind them on how they could be realized. I wanted to demonstrate what could be possible, in what direction and to what dimensions we could be thinking now.”

![]()

![]()

Berlin‘s Pflanzenschutzamt (Plant Protection Office), built from 1986-1989, is Kremser’s last realized building. It is a demonstration of yet another construction method, where only the floor plates are cast with fluid concrete in earthen moulds and then lifted into place. A more conventional method therefore, but one which allows for the construction of much larger structures – even high-rises could be made using this method he claims. (Photos: E. Kremser)

-

In 1969 Kremser made a series of 17 collages. He took pictures of the new buildings in Berlin-Charlottenburg that annoyed him the most, primarily modern “boxes”, then replaced them with his own ideas. In this picture you see his alternative to the SFB building on Theodor-Heuss-Platz.

-

![]()

»I wanted to demonstrate in what direction and in what dimensions we could be thinking now.«

![]()

Kremser’s alternative visions for: Ernst-Reuter-Platz (above), Europa Center on Breitscheidplatz (right). (All images: Engelbert Kremser, 1969)

-

Is he unhappy that these studies have not become reality? Or does he sense that these buildings absolutely could not have been realized that way back then, at least not with the same intensity and convincing energy that one finds in his collages? “No, no, I really wanted to build them. Of course, these are not finished designs. They are ideas for a different way of thinking. For many decades now, our cities have been built mainly of bland boxes – and the problem is that most people have grown accustomed to them. This familiarity with the boxes must first be overcome. People need to learn again to think about the built environment in a much more open-minded way. Time and again, people have come to me and said: ‘Those are fascinating ideas, but I have rectangular cabinets and a rectangular bed – how can they fit into your crooked building?’ Isn’t that tragic? I always answer: build them yourself. Every idiot can shop at IKEA! But to build something yourself, to grapple with it – to explore the object completely and then design it to your own needs and make it with your own hands – that’s the greatest joy.”

![]()

This could have been the Urania, on the corner of Kleiststrasse in central Berlin. -

In 1990 Kremser left the city, moving into a little house in Potsdam where he has been working ever since, primarily with his own hands: laying colorful mosaics in the paths and on the walls, building his own furniture and lamps, painting, and drawing. Is this his retreat from architecture and – even more – from a building industry which determines the form of most buildings as that of the despised box?

“Not at all. I have never turned my back on architecture. It is just that I am not building at the moment because I have no clients. But painting and architecture were never different things for me. I am building on paper and waiting for the right client. Someone who appreciates my kind of architecture and wants to engage with it. Maybe even someone who wants to do some hands-on work with me. It’s such a joy to give shape to things with your own two hands.” Engelbert Kremser will celebrate his 75th birthday in December 2013. I guess he would agree if I describe him as a happy man.

![]()

![]()

Engelbert Kremser: “Im Berg” (In the mountain), acrylic paint on canvas, 100 x 155 cm, 2000

-

In the Photo Booth with ...

Jürgen Mayer H.For nearly 20 years, architect Jürgen Mayer H. has lived and worked in Berlin. Since his completion of the Metropol Parasol in Seville in 2011 he has become one of Berlin’s most internationally-known architects. Yet, he has built little in his adopted hometown. We had a photobooth chat with him about the general lack of courage in Berlin architecture today – and if this is now slowly changing.

Interview by Florian Heilmeyer![]()

-

Why did you move from New York to Berlin in 1994?

I had finished my studies at Princeton. Starting to work as an architect in NYC would have meant staying in the context that I had studied in. Also, in 1994 there was this feeling of a great upheaval in Berlin, that the city was reinventing itself, and that there would be amazing opportunities. To me it seemed much more interesting to bring the architectural approach that I had used during my time at Princeton to Berlin, to test it in a new context. In some way, it would have felt stupid not to do so.

-

But the hope that after the fall of the Berlin Wall the city would embrace progressive architecture was not fulfilled. What made you stay?

You’re right: In the 1990s it only took one look at the juries for me to know that I needn’t bother taking part in Berlin’s architecture competitions. It was clear from the start that I wouldn’t have a chance, given my approach. The architecture debate in Berlin was rather superficial, focused heavily on buildings and façades. Although the divides between many other disciplines were already beginning to soften at that time, this wasn’t the case in architecture. It was extremely helpful that I could exhibit my work in New York, so I set up my office to have an international scope from the start. It wasn’t until the completion of our first building in 2002 that we were gradually accepted in Germany as architects.

Still, I have never regretted coming here. Berlin is certainly not an exciting place to be in terms of its current architecture – but it is a place where you can meet and work with an incredible amount of interesting people.

-

That’s true: Berlin is full of interesting people – architects included. But it still has remained a city with a pretty obvious lack of interesting contemporary architecture, with just very few exceptions to this rule.

Of course! After the fall of the Wall, Berlin’s building policy was committed to the reconstruction of an essentially inconspicuous city. Since then, investors have had little interest in unconventional architecture, because they know this means more resistance, which would mean delays – for them it’s simply a greater financial risk. What’s missing here are daring investors and political will.

But I don’t know if this is much different in Berlin than in other cities. You have to look hard to find courageous architecture, no matter where you are.

-

Jürgen Mayer Hermann is a german architect and artist. Born in 1965 in Stuttgart, he studied architecture at Stuttgart University, The Cooper Union (NYC) and Princeton before moving to Berlin in 1994 where he founded his office J. MAYER H. in 1996. The studio focuses on works at the intersection of architecture, communication and new technology. From urban planning schemes and buildings to installation work and objects with new materials, the relationship between the human body, technology and nature form the background for a new production of space.

What is Berlin architecture missing today? And where do we go from here?

The big projects in particular continue to be driven by 1990s standards. There still hasn’t been a counter-model for a different kind of architecture that can stand up to that. I have never understood why in Berlin, and also in the rest of Germany, there is so much public funding and media support for fashion, art, film, and design, but hardly any for young, avant-garde architecture. Innovative architecture should be a central focus of public interest. It’s not so much a loss for the good young architects in Berlin – they can find commissions elsewhere– it’s a loss for the city and its inhabitants.

So, where do we go? In the last few years, a few examples for new kinds of architecture have been appearing all over Berlin...most of them rather small in scale, but this is encouraging anyway. We’ll have to wait and see what is still possible.

![]()

-

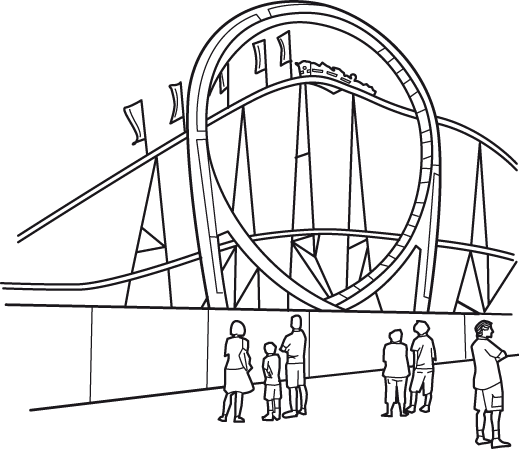

A

City

Soft as

ButterPhotos by Simon Menges, Text by Jeanette Kunsmann

-

![]()

Photographer Simon Menges is a tried-and-tested Berliner: he was born in 1985 in Berlin-Reinickendorf, a district in the northern periphery of what was then West Berlin. At the age of 18 – shortly after the Fall of the Wall – he moved to his first shared apartment in Prenzlauer Berg, then to Friedrichshain, then further east still – to Shanghai. Before going to China, he’d finished studying architecture at the Technical University in Berlin but never actually worked as an architect. “You don’t have to become an architect because you’ve studied it”, he says. “I’ve always loved photography, even before my studies: my thesis was a photographic documentation of Gropiusstadt.”

In Shanghai he spent two years working mostly for David Chipperfield Architects, documenting one of the office’s biggest projects. Three pictures a day. “Strange as it sounds, to me China meant peace and a lot of time.” Since returning to Berlin he has been working as an assistant to German artist Wolfgang Tillmans as well as a freelance architecture photographer, with regular clients including David Chipperfield, EM2N, and Berlin-based Zanderroth Architects.

We met in August 2013 to talk about Berlin. But rather than just talking about the city as a photographer, he wanted to seek out a truly typical Berlin location to photograph as well. That’s how we ended up in the strange hinterland behind Berlin’s central station, currently one of the city’s largest construction sites, which during the summer has become a temporary fairground for the “German-American Volksfest”. While walking around this strange mixture of fun fair, construction site and city centre, we wondered whether in truth Berlin is perhaps just a cheap amusement park where the Easy Jet-set goes on a pub crawl …

![]()

-

![]()

»For me as a child, more than anything Berlin was grey! Much greyer than today!«

![]()

-

![]()

![]()

-

![]()

»People tend to come to Berlin without knowing exactly what they will do here. Either they find a job or work elsewhere while using the city as a home base. Berlin is the quintessence of freedom.«

![]()

-

»Many people who come to Berlin see only Kreuzberg or Neukölln and are excited to talk about it. But then again, many people don’t know much else about the city: for them, Berlin is like living on an island.«

-

![]()

![]()

-

»I don’t experience Berlin as a real metropole, but rather as a place that is in the process of becoming one.«

-

Simon Menges, born 1985, is one of the rare true Berliners in this city. He currently lives in Berlin–Kreuzberg. He works internationally as a freelance photographer. In addition to commissions for David Chipperfield, EM2N, and Zanderroth Architects, he pursues his own projects. Since 2011 he has worked as an assistant for Wolfgang Tillmans. This photo stretch of the Deutsch-Amerikanisches Volksfest was produced in August 2013 in Berlin.

»The path of least resistance is probably what lures many to Berlin. It is a city as comfortable and soft as butter. Life is super easy here, and remains affordable. To live here well takes relatively little effort, compared to other major cities.«

![]()

-

Lukas Feireiss (*1977) is a curator, writer and artist who in his artistic, curatorial, editorial and consultive work aims at the critical cut-up and playful re-evaluation of creative and spatial production modes and their diverse socio-cultural and medial conditions. Lukas Feireiss teaches at various universities worldwide and is visiting professor for space and design strategies at the University of Art and Design Linz, Austria, and is also the editor and author of numerous books and publications He graduated in Comparative Religious Studies, Philosophy and Ethnology from Berlin’s Free University, where he specialized in the dynamic relationship between architecture and other fields of knowledge.

Since 2010 he has run Studio Lukas Feireiss, an interdisciplinary creative practice focused on the discussion and mediation of architecture, art and visual culture in the urban realm.

![]()

![]()

(Photo: Ina Schoenenburg / artberlin.de)

![]()

Lukas Feireiss

Berlin-born curator, writer and artist Lukas Feireiss loves his hometown – mythos included – but has doubts about where it might be heading.

![]()

»Every city is to some extent both beneficiary and prisoner of its own myth and cliché – and Berlin is a prime example of this phenomena. With every new Berliner coming into town, this city constantly reinvents and revives its own particular myth: that of creative capital and libertine playground.«

»I generally love the rough architectonic collage that the inner city is made of. Things constantly clash without clashing. And life in Berlin is still largely neighborhood-based. Each district of the city offers almost everything you need – theater, cinema, galleries, museums, shopping – so little movement is necessary.«

»We are at a pivotal point in the development of the city, in danger of losing exactly what made Berlin so attractive in the first place: freedom of space, unpretentiousness in attitude and low rents. We’re currently taking a wrong turn towards mainstream city development.«![]()

-

![]()

![]()

Ellen Blumenstein

Ellen Blumenstein has been chief curator of KW Institute for Contemporary Art since January 2013. KW’s main building, set back by a courtyard from Auguststraße in Berlin Mitte, is a former margarine factory that was renovated to become an art space in the 1990s, and has since become emblematic of Berlin’s international art scene after the fall of the wall. Yet Mitte’s changing identity in recent years – now dominated by private collections, boutiques, and tourism – has changed KW’s immediate context and public, a fact that Blumenstein addresses head-on.

![]()

(Photo © Edisonga courtesy KW)

-

Ellen Blumenstein

Ellen Blumenstein, 1976 born in Witzenhausen, Germany, lives and works in Berlin, and has been chief curator of KW Institute for Contemporary Art since January 2013. Her first projects included the exhibitions Relaunch, Kader Attia: Repair. 5 Acts, and the launching of a comprehensive new events program. Prior to this she was an independent curator, member of curatorial collective THE OFFICE and founder of project space Salon Populaire. Between 1998-2005 she worked as a curator for KW, realizing amongst other projects, the exhibition Regarding Terror: The RAF-Exhibition (with Klaus Biesenbach, Felix Ensslin, 2005). More recently her exhibitions have included Between Two Deaths at ZKM in Karlsruhe (with Felix Ensslin, 2007) and Agulhas Negras — On the necessity to Discuss Social Functions of Contemporary Art in São Paulo/Campos do Jordão, Brazil (2008). In 2011 she was the curator for the Icelandic Pavilion at the Venice Biennial.

![]()

»The first time I came to Berlin was in my early twenties to go to the Love Parade with some friends. I was living in Hamburg and studying literature and music, and Berlin felt too big and uncontrollable for me. But after working for Documenta X in 1997 and falling in love with art, I was quickly convinced that Berlin was the city where I’d have to go; the move felt right from the moment I stepped onto the platform at Bahnhof Zoo and found an apartment within half a day on Kastanienallee in Prenzlauerberg.«

»The city's problem in the future will be a lack of artists and practitioners who engage with their habitat; it needs places where segmented groups and practitioners can cross-over and become visible to a broader audience so they can make an impact. This is a task for KW – we are working with partners like the magazine Arch+ and a network of Berlin project spaces to develop strategies to use our institutional power and impact for both political purposes and for visibility.«

»The city has already been lost as the city of producers that it was appreciated for being by creatives from all over the world in the past decades. In the broadest sense in terms of city planning and development and in positioning itself towards contemporary culture, politicians in Berlin have been entirely uninspired and shortsighted about imagining a future city. We have witnessed the economic development of our city without being able to do anything about it. It is too late to lock the stable door after the horse has bolted, so what has to be done now is to insist on keeping the last remaining spaces – in the literal sense as well as in terms of spaces for thought – open, with whatever means seem appropriate.«

![]()

-

Karin Sander (* 1957 Bensberg, Nordrhein-Westfalen) is an artist who lives and works in Berlin and Zurich. She exhibits internationally, with previous solo exhibitions in Auckland, New York, Tokyo amongst other places. Most recently she has had solo shows at the Humboldt Lab Dahlem, Berlin, Lehmbruck Museum, Duisburg (both 2013), the Staatliche Kunsthalle, Karlsruhe (2012), Neuer Berliner Kunstverein (2011), Kunstmuseum St. Gallen (2010) and K20 Kunstsammlung NRW, Düsseldorf (2010).

Since 2007 she has been a professor at ETH Zurich Swiss Federal Institute of Technology and from 1999 to 2007 Sander was a professor at the Kunsthochschule Weissensee, Berlin.

![]()

![]()

Karin Sander

The artist Karin Sander starting commuting to Berlin in 1999 when she began a professorship at the Kunsthochschule Weissensee, finally moving to the city in 2003. She lives in an apartment attached to her studio, both designed in collaboration with the architects Sauerbruch Hutton.

![]()

»One characteristic of living in this city? That we all keep talking about it.«

The artist Karin Sander in her apartment. (Photo: Noshe)

-

![]()

-

![]()

![]()

Downtown in Columbus, Indiana: IM Pei’s Bartholomew County Public Library Plaza (1969), Eliel Saarinen’s First Christian Church (1942), and Henry Moore’s Large Arch (1971). (Photo courtesy Columbus Area Visitors Center)

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Tradition is a dare for innovation.«

Alvaro Siza

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents