-

Magazine No. 18

Slovenia!

-

No. 18 - Slovenia!

-

page 02

Slovenia!

An insiders' view

-

page 03

Editorial

Slovenia!

-

page 04 - 13

Design, Decline and Dogma

Interview with museum director Matevž Čelik on the status quo of Slovenian design

-

page 15 - 16

Planica Nordic Ski Centre

Designed by Abiro

-

page 17 - 18

Cultural Centre of EU Space Technologies (KSEVT)

Designed by Bevk Perović, dekleva gregorič, OFIS, Sadar + Vuga

-

page 19 - 22

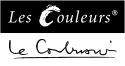

Cross Country Cover

Architect Boštjan Vuga does a flypast of regional roofscapes

-

page 23 - 24

A Plethora of Plečnik

Godfather of Slovenian modern architecture

-

page 25 - 32

Revolution without Patricide

Miha Dešman on what defines contemporary Slovenian architecture

-

page 33 - 34

Ptuj Performance Centre

Designed by ENOTA

-

page 35 - 36

Bohinj Bicycle Bridge

Designed by DANS arhitekti

-

page 37 - 44

Nobody Loves the Hitler Beetle

Interview with artist Jasmina Cibic on cultural identity and the politics of display

-

page 45 - 50

Repeat Offenders

Vid Zabel and Katarina Čakš revisit Slovenia's homegrown Brutalism

-

page 51 - 52

Air Traffic Control Centre

Designed by Sadar + Vuga

-

page 53 - 54

Buy Me a River

Maša Ogrin on the River Ljubljanica renovation

-

page 55 - 61

Sylvan Structures

Rok Oman and Špela Videčnik of OFIS Arhitekti on their love affair with wood

-

page 62 - 66

In the Photo Booth with...

Sou Fujimoto

-

page 67 - 70

Bookmarked

Guest reviewer bookshop Pro qm

-

page 71

Klaustoon

XII. The Big FAT Kill

-

page 72

Next

Space: it's time to leave the capsule if you dare...

-

-

uncube’s editors are Sophie Lovell (Art Director, Editor-in-Chief), Florian Heilmeyer, Rob Wilson and Elvia Wilk. Graphic design: Lena Giovanazzi.

uncube is based in Berlin and is published by BauNetz, Germany’s most-read online magazine covering architecture in a thoughtful way since 1996.

![]()

SLOVENIA!

We have scaled down a little this month and gone local with a young central European country of just two million inhabitants. Bordered by the Alps, the Carpathian Basin and the Mediterranean, Slovenia may be tiny, but its landscape and culture are as varied as its recent history. This mix provides fertile ground for some of the most exciting contemporary architecture in Europe.

uncube asked Slovenian architects, artists, journalists and curators to share their views on the defining ingredients of their country’s building, art and design culture in their own words. The result is a fascinating patchwork of politics, Plečnik, tradition and rebellion.

Welcome to the uncube insiders’ guide to SloveniaCover Photo: ENOTA architects' Podčetrtek Traffic Circle, 2012 © Miran Kambič

This page: © Miran Kambič

-

Design,

Decline

and

DogmaInterview with Matevž Čelik

by Sophie Lovell

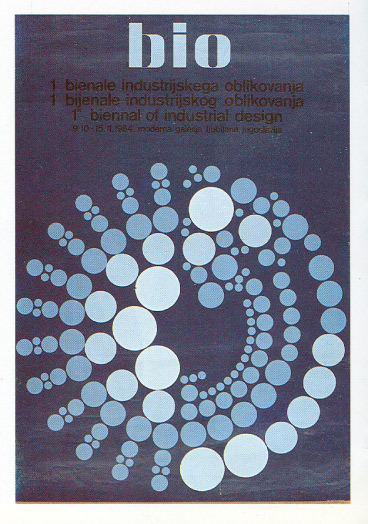

1st Biennial of Industrial Design (BIO 1), exhibition display, 1964, Ljubljana. (All images, unless otherwise stated, courtesy MAO archive)

-

![]()

The director of Ljubljana’s Museum of Architecture and Design (MAO) and organiser of the BIO Design Biennial, Matevž Čelik is an architect from a generation straddling the cultural divide between the state-socialism of former Yugoslavia and the burgeoning free-market economy of the young Slovenian nation. He spoke to Sophie Lovell about how the knock-on effects of political change have affected the country’s design industry and the difficulty of finding new models of engagement whilst hamstrung by the old.

You are a trained architect and had your own practice until 2010 when you took over the directorship of the MAO. What led you to take that step? What did you hope the museum would give you that designing buildings did not?

At the turn of the millennium, Slovenia was a country in which it was easier to carve out an independent career than elsewhere, but at the same time architecture was produced and communicated in a way that was still deeply rooted in the past. As young architects building our first projects we strongly felt this gap. So in 2002, together with Dekleva Gregorič and Bevk Perović architects and others, we founded the Trajekt Institute for Spatial Culture. Trajekt organised exhibitions and workshops and communicated mainly via the internet. It soon became a locus of architectural debate in Slovenia. I edited the Trajekt website and moderated discussions for eight years, so moving to the museum was a logical step in extending communication and reaching the general public.

From the nineteenth century onwards, during the period in which design as a discipline was taking shape worldwide, Slovenia went through several identity changes as a nation. How do you think this has affected Slovenian design – both stylistically and in terms of practice?

Design in Slovenia carries the genes of the Austro-Hungarian craft schools, the Bauhaus tradition as well as post-war socialist modernisation in Yugoslavia. It began with Jože Plečnik, who visited the Craft School in Graz and studied and collaborated with Otto Wagner in Vienna. -

Another key moment for the development of modern design in Slovenia was 1961, when Edvard Ravnikar [Plečnik’s former student and Slovenia’s second most famous architect. Eds.] set up an experimental design course at the Ljubljana Faculty of Architecture. The course leaned conceptually towards the Bauhaus and the Hochschule für Gestaltung in Ulm, where Ravnikar collaborated with Max Bill. The course itself didn’t survive, but later the same methods were revived at the Department of Design at the Academy of Fine Arts, established in 1984.

»To this day, design in Slovenia has remained committed to modernist reductionism, subordinated to function, ergonomics and rationalisation for the purpose of mass production.«

To this day, design in Slovenia has remained committed to modernist reductionism, subordination to function, ergonomics, and rationalisation for the purpose of mass production. The belief that the role of design in society should be connected to industrial production is still deeply rooted within the Academy’s product design department.

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

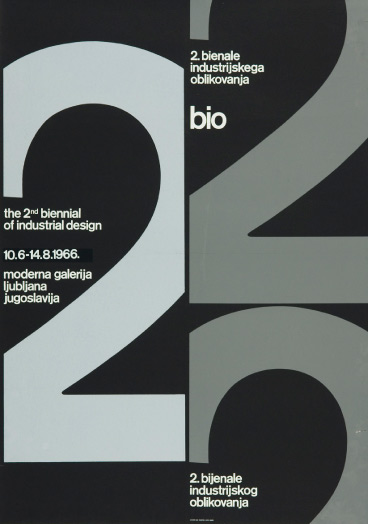

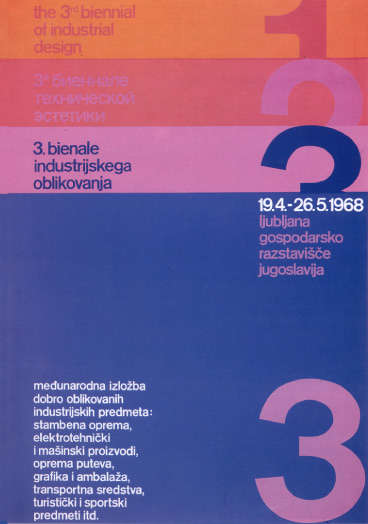

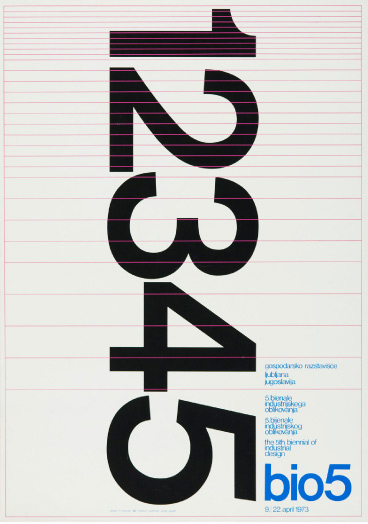

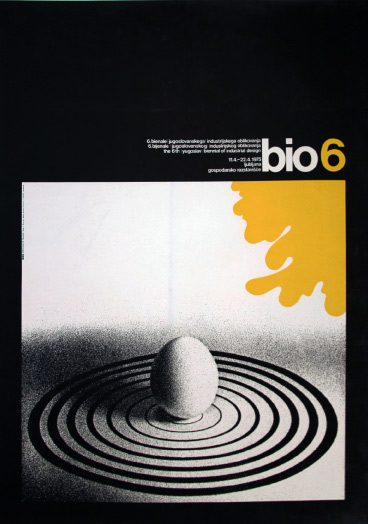

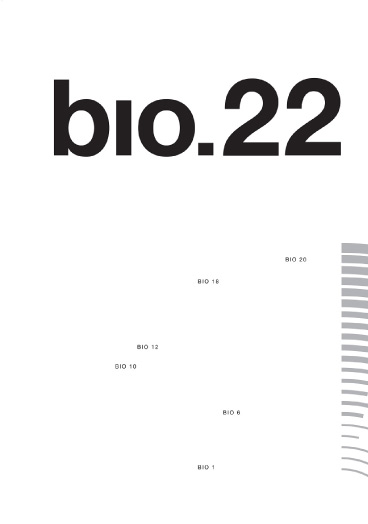

Posters for early BIO exhibitions: Majda Dobravec, BIO 1, 1964; Mihailo Arsovski, BIO 2, 1966; Grega Košak, BIO 3, 1968; Grega Košak, BIO 4, 1971; Mihailo Arsovski, BIO 5; Matjaž Vipotnik, BIO 6, 1975; Gigodesign, BIO 22, 2010; Radovan Jenko, BIO 13 (from set of three), 1992. (All images courtesy MAO Archive)

-

This year the Slovenian Biennale of Design, (BIO) founded in 1964, will be 50 years old. This must make it one of the oldest events of its kind in the world. Why was it founded and why do you think it has endured?

![]()

BIO 5 exhibition display; designer: Saša J. Mächtig, 1973.

BIO is the oldest design biennial in the world. In former Yugoslavia the 1960s were years of industrial growth, optimism and opening up to the world.After the war, modernisation through industrialisation was high on the agenda of the socialist government.

The Biennial of Industrial Design has always been associated with the development of industry, and the efforts to enrich and humanise mass-produced objects for every home were seen as clear proof of socialist welfare. These ideas were still strongly present at BIO in the 1990s, although the bloody disintegration of Yugoslavia and restoration of capitalism in Eastern Europe called them into question. In 2012 we started to think about possible alternatives. Now with the 50th anniversary edition, the role of the design biennial in the future is becoming much clearer.

I have heard that in its time the BIO was as important for the European design scene as the Salone del Mobile in Milan is now. Was it the Eastern Bloc counterpoint? Or did it have an international presence?

There was always strong international presence at BIO from the beginning. The biennial in itself can be seen through different lenses. By comparing the latest everyday products from the East and West, BIO was probably a platform that intended to supply tangible proof that socialist prosperity could compete with and exceed that of capitalism. And until the fall of the Berlin Wall BIO was a window for the West, through which it was possible at least to peek at Eastern bloc production. But in fact it was mostly a local professional initiative. The local designers and architects who established and ran BIO always saw the biennial as a natural integration of their work within the international world of design.

![]()

ATA 30 Iskra telephone, 1965, by Davorin Savnik. (Photo courtesy Technical Museum of Slovenia)

-

»It is necessary to break with the fetishisation of products that has alienated design from production.«

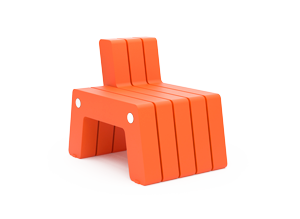

Asobi's “Isle lounge″ chair, 2005. (Photo courtesy Asobi)

-

Many European countries are having to rethink their industries as manufacturing businesses struggle – and Slovenia is no exception. What used to be the key areas of industrial design and manufacturing in Slovenia and how are they faring today?

As the most developed and industrialised part of former Yugoslavia, with state owned companies that had successfully exported to the West, Slovenia was well-placed in the 1990s.

![]()

Asobi's “Ljubljana chair”, 2013. (Photo courtesy Asobi)

However, it responded wrongly to the challenges of economic transformation. The process of de-industrialisation in Slovenia coincided with the restoration of capitalism and the privatisation of state-socialist enterprises.

Slovenia opted for a protectionist approach in which the government favoured the transfer of shares to local owners. It worked well for a time, but during this redistribution of power, rather than providing companies with visionary and responsible managers, a new economic elite emerged, who played primarily on their links with political parties and access to public money.

During these years the traditionally strong wood, furniture and textile industries virtually disappeared. Many factories no longer exist. Instead of investing in restructuring and modernising production, transactions over the last 20 years revolved within a closed circle of semi-state-owned banks and enterprises. When Europe entered the crisis, the Slovenian economy imploded and the cream of our companies were lost. On the other hand, now many new small companies are emerging, run by intelligent people who are looking for niche products, thinking long term, and enthusiastically developing their business models in accordance with social responsibility.

What problems need to be overcome?

In my opinion one of the big problems in Slovenia is the expectation that big players or systems, either economic or governmental, will solve the everyday problems of every individual.

![]()

Niko Kralj's “Rex Chair”, 1952, for Stol Kamnik.

Everyone wants to have a job but there are very few who think about how to create new jobs. If design is to develop, designers shouldn’t wait for clients to ask for something to be designed.

-

Silent Revolutions: Contemporary Design in Slovenia, travelling exhibition premiered in 2011.

-

What areas and strategies of design are on the rise?

The design scene in Ljubljana is very lively. The young generation realises that the role and influence of traditional industrial manufacturers in the market have decreased. For instance, people gathered around a group called Rompom to organise Pop-up Dom, a flexible peer-to-peer network. This is replacing the rigid top-down production models designed to optimise the mass production industry in the last century. Crowd funding platforms are just one of the tools that speak of new production models for our time. Designers act as facilitators and they organise co-working spaces or other services for designers. Another new initiative is Gigodesign’s recently launched Design Forward Accelerator, a service that includes seed money in cash, services, workspace and mentorship. Crisis also acts as a powerful engine for change in design.

»Everyone wants to have a job but there are very few who think about how to create new jobs.«

How big a role do natural resources and materials and local skills play in contemporary design in Slovenia?

Wood, glass, textiles, metalworking, and also expertise in the chemical industry, where new materials are developed, have always been important for Slovenian design. In the past, it was the manufacturers who dictated the use of these materials. Over the last two years MAO has presented the exhibition Silent Revolutions at various design events around Europe, which showcases contemporary design from Slovenia. The products in the exhibition show that designers are the ones increasingly suggesting use of natural resources and local skills to producers.

-

Matevž Čelik is an architect, architectural researcher and writer. In 2002 he co-founded Trajekt, Institute for Spatial Culture in Ljubljana. He contributed to Oris magazine in Zagreb and published a book New Architecture in Slovenia (Springer Wien New York, 2007). Since 2010 he has been head of the MAO, Museum of Architecture and Design in Ljubljana. Under his leadership the MAO has established a new programme of exhibitions and debates including Architecture Live, Open Depot, Designing the Republic and Under a Common Roof. He is a member of the team of experts for the European Prize for Contemporary Architecture – Mies van der Rohe and also a member of the international jury for the European Prize for Urban Public Space 2014.

What direction would you like to see the BIO take over the next 50 years and what role do you wish the MAO to play – in short where would you like to take it?

Right now we are facing the challenge of finding new solutions with almost no available resources for research and development of new models within existing economic structures. Production has been divorced from expertise and the two need to be reconnected. It is necessary to break with the fetishisation of products that has alienated design from production. I believe that BIO should play a role in this field and strive to support creativity in its most delicate and vulnerable stage. This means that in the future, BIO has to increasingly play a research-based, experimental role. p

![]()

Image: Pop-up Dom Strictly Analog Festival. (Photo: David Lotrič) Video: RomPom's “Pop-up Dom 2013” produced by Blueroom.si

-

![]()

Architect: Abiro

Landscape Architect: Studio AKKA

Location: Planica

Client: Government of Slovenia

Date: 2011The two historic ski-jumps HS104 (left) and HS139 at the Planica Nordic Ski Centre, with contemporary additions by Abiro. (Photo: Miran Kambič)

-

Abiro were founded in 1998 by Miloš Florijančič, he now runs the practice with Matej Blenkuš. Their work is characterised by innovative spatial design and construction detailing, combined with the different geographical, historical and social environmental factors conditioning each project.

Other projects have include the Imparo commercial and storage building, Ljubljana, (2011); Grosuplje library, Ljubljana (2007); Dunajski vogal residential building, Ljubljana (2006); Šarabon multi-storey car park and commercial building, (2006); Šmartinka multi-purpose building, Ljubljana (2002); the Faculty of Architecture extension, Ljubljana (1996).

This project saw the renovation of an historic ski-jumping centre joined by the construction of a new cross-country skiing facility.

Protected as Slovenian national heritage, the original centre, dating back to the 1920s, has clocked up more world records than any other. It includes what was once the highest jump in the world, designed by the brothers Lado and Janez Gorišek in the 1960s, so high it was where the term “ski-flying” was invented.

The complex has been augmented by a series of bold sculptural structures and interventions by Abiro, offering new technical and visitor facilities, which means it can again play host to top-level international competitions.![]() (rgw)

(rgw)![]()

The sculptural belly of one Abiro’s improvements to a ski-jump at the Planica Nordic Ski Centre. (Photo: Miran Kambič) -

![]()

Architects: Bevk Perović arhitekti, dekleva gregorič arhitekti, OFIS arhitekti, Sadar + Vuga

Location: Vitanje

Client: Municipality of Vitanje, Ministry of Culture

Date: 2012Main entrance of the Cultural Centre of EU Space Technologies (KSEVT). (Photo: Miran Kambič, courtesy dekleva gregorič)

-

Bevk Perović arhitekti

Founded by Matija Bevk and Vasa Perović in Ljubljana in 1997.

www.bevkperovic.com

dekleva gregorič arhitekti

Founded by Aljosa Dekleva and Tina Gregorič in Ljubljana in 2003.

www.dekleva-gregoric.com

OFIS arhitekti

Founded by Rok Oman and Špela Videčnikin in Ljubljana in 1996.

www.ofis-a.si

Sadar + Vuga

Founded by Jurij Sadar and Boštjan Vuga in Ljubljana in 1996

www.sadarvuga.com

Visually echoing a crashed saucer, the interlocking aluminium-clad cylinders of this building speak of outer-space. Its form was inspired by a revolutionary 1929 design for a space station by rocket engineer and local-boy-made-good Herman Potočnik Noordung.

The shape also expresses the building’s dual nature: integrating a community centre and library with a Museum of Space Technologies. The exhibition spaces ramp up to research areas, around a central circular multi-purpose hall holding up to 300 people and used for anything from town meetings to scientific seminars. Unusually, the project was jointly designed by four Slovenian practices, its concept arrived at in a series of workshops.![]() (rgw)

(rgw)![]()

Central space the Cultural Centre of EU Space Technologies (KSEVT). (Photo: Tomaž Gregorič) -

Cross

Country

CoverArchitect Boštjan Vuga does a flypast of regional roofscapes

Sadar + Vuga’s Football Stadium and Multipurpose Sports Hall in Stožice, Ljubljana. (Photo: Žiga Čebašek)

-

Just 168 kilometers long and 248 kilometers wide, Slovenia is a tiny country but is blessed with great geographical diversity. Two hours in a fast car on a highway through Slovenia can feel like driving in a video game. If you drive from west to east starting at the coast, you pass through the rocky Karst, then the green, forested heart of the country and up into the alpine mountains before descending through a hilly landscape and into the endless plains of Pannonia in the Carpathian Basin.

Move into the air. Flying in a helicopter over the country you’ll discover a smooth transition of different shades: of woodland greens, rocky greys, and the blue hues of the sea, lakes and rivers. And then there are the villages, settlements, towns and cities. Various local natural characteristics are grafted onto the roofscapes of each particular region: a consequence of changing climatic conditions and the available resources for construction.

![]()

Velika Planina, a herders’ settlement in northern Slovenia. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

-

Razgledi Perovo Housing by dekleva gregorič in Kamnik, Slovenia, 2011. (Photo: Miran Kambič)

-

Sadar + Vuga was founded by Jurij Sadar and Boštjan Vuga in Ljubljana in 1996, focusing on open, innovative and integral architectural design and urban planning. Projects include the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Slovenia, which received the Bauwelt Prize (2001); the new entrance hall for the National Gallery of Slovenia; the Mercator Shopping center; and the housing projects Condominium Trnovski Pristan and House Gradaška, which were both recipients of prizes and nominations for the Mies van der Rohe Awards. Recent projects have included the Sports Park Stožice in Ljubljana, a new air traffic control centre at Ljubljana airport, and the Cultural Center of EU Space Technologies in Vitanje, Slovenia.

So the pitches of roofs, their materials and colours, change as fast as the natural geography. You pass over the almost flat red brick roofs of the coastal region, loop over steep wooden shingled dwellings in the Alps and the thick thatches of the plains. Each region is identifiable by its roof colour alone. These traditions of building construction smoothly translate into contemporary architectural production. The ancestry of the roofs perched above many new buildings in Slovenia is easy to trace, as they share similar materials and pitches with traditional ones – inhaling the climatic parameters of their particular region, yet more relaxed in shape and volume.

Thus new roofs extend to the ground, rise up in zigzags or become huge inclined surfaces. Sometimes it’s difficult to distinguish where a building stops and the natural landscape begins. Even modernist residential towers in Slovenia have rooftops that reflect where they belong: sheltering triplex apartments echo the mountains beyond.

The two roofs of our own Stožice complex, for example, a stadium and sports hall in Ljubljana, are clad in aluminium shingles whose colour shifts between silver and gold, depending on the weather or time of day. This means that even at their vast scale, the sports complex roofs almost merge into the natural context and contours when viewed from a distance.

Go to Google Earth. Check out Slovenia. On your interactive screen, you can hardly distinguish human construction from preserved nature. The roofs are landscapes, the landscapes are roofed.

![]()

![]()

Shopping Roof Apartments in Bohinjska Bistrica by OFIS. (Photo courtesy OFIS)

-

![]()

A Plethora of Plečnik

Jože Plečnik: Church of St. Michael, 1940, Ljubljana Marshes. It combines features from both Greek temples and the churches of the Slovenian Kras region. The main building’s structure is made of wood. (All photos: Miran Kambič)

![]()

-

In this issue barely one of our guest contributors, writers and interviewees fails to mention the figure and influence of Jože Plečnik (1872-1957), godfather of Slovenian modern architecture.

Born in Ljubljana, Plečnik studied architecture in Vienna with the Secessionist architect and town-planner Otto Wagner, going on to work in his office and designing a series of buildings that began to exhibit his distinctive style. He then moved on to Prague where he most famously worked on the renovation of Prague Castle, and a remarkable series of interventions there. Only in 1921 did Plečnik move back to Ljubljana, beginning the project for which he is most celebrated: the redesign of the city after the fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Plečnik’s interventions in Ljubljana, centred on the river and the public spaces and routed around it, are credited with imbuing the city with its identity today. He also designed key buildings in Ljubljana such as the National and University Library, the Central Market, the Križanke Summer Theatre and the Bežigrad Stadium. Plečnik’s balance of classical architectural influences with a modern and innovative approach continues to be cited as a major influence by practicing Slovenian architects today.

![]() (sl)

(sl)![]()

Jože Plečnik's Jožamurka Pavilion in Begunje na Gorenjskem village near Radovljica. (Photo: Miran Kambič)

![]()

-

Revolution

without

PatricideText by Miha Dešman

Architect Edvard Ravnikar’s plan for his Revolution Square (Trg Revolucije) in Ljubljana, circa 1970. (Image courtesy MAO archive)

-

Miha Dešman of DANS arhitekti is one of Slovenia’s leading architects and architecture writers. For uncube he tackles the tricky topic of trying to define the nature of contemporary Slovenian architecture and suggests that, for all its rebellious reputation, it is still very much a chip off the old block.

No serious interpretation of contemporary Slovenian architecture is possible without taking into account the meltdown of the Socialist socio-political system in the early 1990s and the subsequent transition. For all of us who spent our childhood and youth in the Socialist era but were never active participants in those times, this experience has made us who we are. The experience is one of being both “before” and “now”; of being both without Europe and within.

The excitement at the time about the “brave new world” of capitalism, the universality of the market economy, and the globality of the internet was initially reflected in architecture, which became plural, superficial, and irresponsible with respect to global issues. One may ask to what extent contemporary Slovenian architecture has retained any sort of cultural identity, or whether it is only a reflection of current global activity.

It is my belief that after independence in 1991 Slovenian architecture has been equally concerned — if not more so — with maintaining the continuity of the past as it has been with parroting the West. Allow me to elaborate. Slovenian architecture for the greater part of the twentieth century was obsessed with creating its identity. This is likely an expression of a century’s worth of unrealised tendencies towards national independence. Slovenia has for centuries existed as partitioned national territory (with varying degrees of autonomy) contained within stronger neighbouring states, including Austria, Italy and Yugoslavia. The end of the century was marked by fierce struggles for cultural survival, unification, and retention of territory.

The hierarchical structure of the Slovenian architecture and urban design cosmos during the last century was, and to a certain extent still is, analogous to a pyramid, with Jože Plečnik (1872-1957) at the top, Edvard Ravnikar (1907-1993) below, and a multitude of others spread out at the bottom. A desire for historical continuity reinforced by the respect for tradition and attachment to teachers is particularly pronounced in Slovenia.

-

Edvard Ravnikar’s Revolution Square after completion, mid-1970s. (Photo: Janez Kališnik, courtesy MAO archive)

-

![]()

Matej Vozlič's Linde M.P.A. Office Building in Ljubljana, 2006.

(Photo: Blaž Budja)![]()

»Any attempts to break away from Plečnik have always seemed like adolescent deviations rather than full revolt.«

![]()

Bevk Perović Arhitekti's House D in Ljubljana, 2008. (Photo: Miran Kambič)

Ambient's Bežigrajski dvor office building in Ljubljana, 1996. (Photo: courtesy Ambient)

-

This may be partially due to a Christian, rural mentality with its attachment to the soil and ethnic roots. Therefore, while patricide is required to incite revolution, any architectural attempts to break away from Plečnik – and then, in turn, from Ravnikar – have always seemed more like adolescent deviations rather than full-on revolt. The result has always been a return to the old positions. This dialectic is still at work today. Each new generation begins by pronouncing itself as the bearers of new, progressive ideas, but then history catches up. A good example here would be Sadar + Vuga, who so radically broke with the past at the beginning of their careers with publications such as Formula New Ljubljana and Sixpack Catalogues, and yet now cite Plečnik as a direct inspiration for their work in their latest monograph.

The start of the new millennium was full of promise. Slovenia was lucky enough to have a market that was thirsty for architecture and architects who were ready for action. A new generation of emerging architects graduated in Slovenia and went on to leading international schools, such as the Berlage Institute in Rotterdam, AA in London, and Columbia in New York, for their postgraduate studies. Upon returning, their built work was praised as an excellent response to the global demands and challenges; superior, even pioneering architecture started to be created and one could begin to see Slovenia as a potential architectural epicentre. So how did this reversion happen?

Drastic political transition has social side effects. During the struggle for independence and immediately after, a laissez-faire attitude toward cultural and social space opened the doors for experimentation, oscillations and even exceptional achievements that weren’t possible elsewhere due to tighter regulations. In hindsight, the extent of the avant-garde at this time may have had something to do with the extremely fast balancing of cultural differences. Similar to an equalisation in air pressure, there is turbulence followed by a period of calming down.

Slovenia joined the EU in 2004, and entered the European monetary union in 2007. These two acts made it at least look like a normal country, and Slovenians were duly faced with the best capitalism has to offer: an economic crisis, growing social differences, the decline of the middle class, unemployment, and the impoverishment of the intellectual and creative professions. Today, generations of young (and not-so-young) architects are frozen in various stages of their careers. -

![]()

DANS arhitekti's Hospic in Ljubljana, 2010. (Photo: Damjan Švarc)

»Today, generations of architects are frozen in various stages of their careers.«

![]()

Maruša Zorec's Grajska Pristava manor building in Ormož, 2011. (Photo: Miran Kambič)

-

“Llstol”, designed by architecture student Luka Ločičnik in 2012, is a multi-functional lounge chair. (Photo courtesy Luka Ločičnik)

-

Miha Dešman was born in 1956 in Gornji Grad, Slovenia. He studied at the Ljubljana Faculty of Architecture and the IUAV in Venice, Italy. He has been a freelance architect and member of DESSA since 1981, and a member of DANS architects since 2004. Since 1995 he has been executive editor of the architecture theory magazine AB and is the author of numerous articles and essays. He was president of the Architect’s Society of Ljubljana between 2003 – 2006 and president of the executive board of the Plečnik Prize. Dešman received the Piranesi prize in 1990 and the nomination for the Plečnik Medal in 2004, among other prizes. His works have been shown at over 30 international exhibitions.

www.dans.si

With the ascent of the economic crisis, a number of major projects by international architectural celebrities have come to a halt; in most cases this is a blessing, since they only offered square footage in generic high-rises. On a symbolic level, we have retained our innocence once again.

For the youngest generation receiving its education at Ljubljana’s well-regarded faculty of architecture, going and working abroad is the rule rather than the exception. They see architecture a different way; instead of conceited hubris, now modesty, fairytale motifs, and a desire for closeness are de rigueur. The young are heralding a new period in which architects are precarious design labourers on the one hand, and on the other, they are beginning to realise that they need to become useful again if they are to survive. They feel that they have to adapt to new, harsh social and economic conditions, and that their work must be directed at common, real and humane values.

Today, wood, steel and brick find textural expression in a number of new Slovenian building works and there is an abundance of façade patterning. Architects dress houses with pixels on cladding and roofs, with aluminium, timber, or fibre concrete panels, perforated or otherwise textured, to attain the desired effect. Slovenian architecture is obsessed with form and detail, while the ambient and the experimental tend not to stand out. The potentials of space are taken advantage of considerably less than those of surface and form. Slovenian architecture can be conceptual, but its concepts are rather unidirectional.

Architecture is not just an uninterrupted continuum of tradition, nor is it the result of the conditions in which it was built; architecture is a practice that is established and verified when it is upset. In this sense, the responses to the crisis may be different, but the reaction, whatever the shape, must be swift. Young Slovenian architects want to establish a difference. This is as it should be — every new generation has to perform and endure a divorce from previous ones if it wants to build its own core and identity. This hasn’t happened yet, though; the project is still in an embryonic state. The revolt against the dominance of the previous generation is not yet sufficiently formed as to receive its final expression. p -

![]()

![]()

(All photos: Miran Kambič)

Architect: ENOTA

Location: Ptuj, Slovenia

Client: Ptuj Municipality

Date: 2013 -

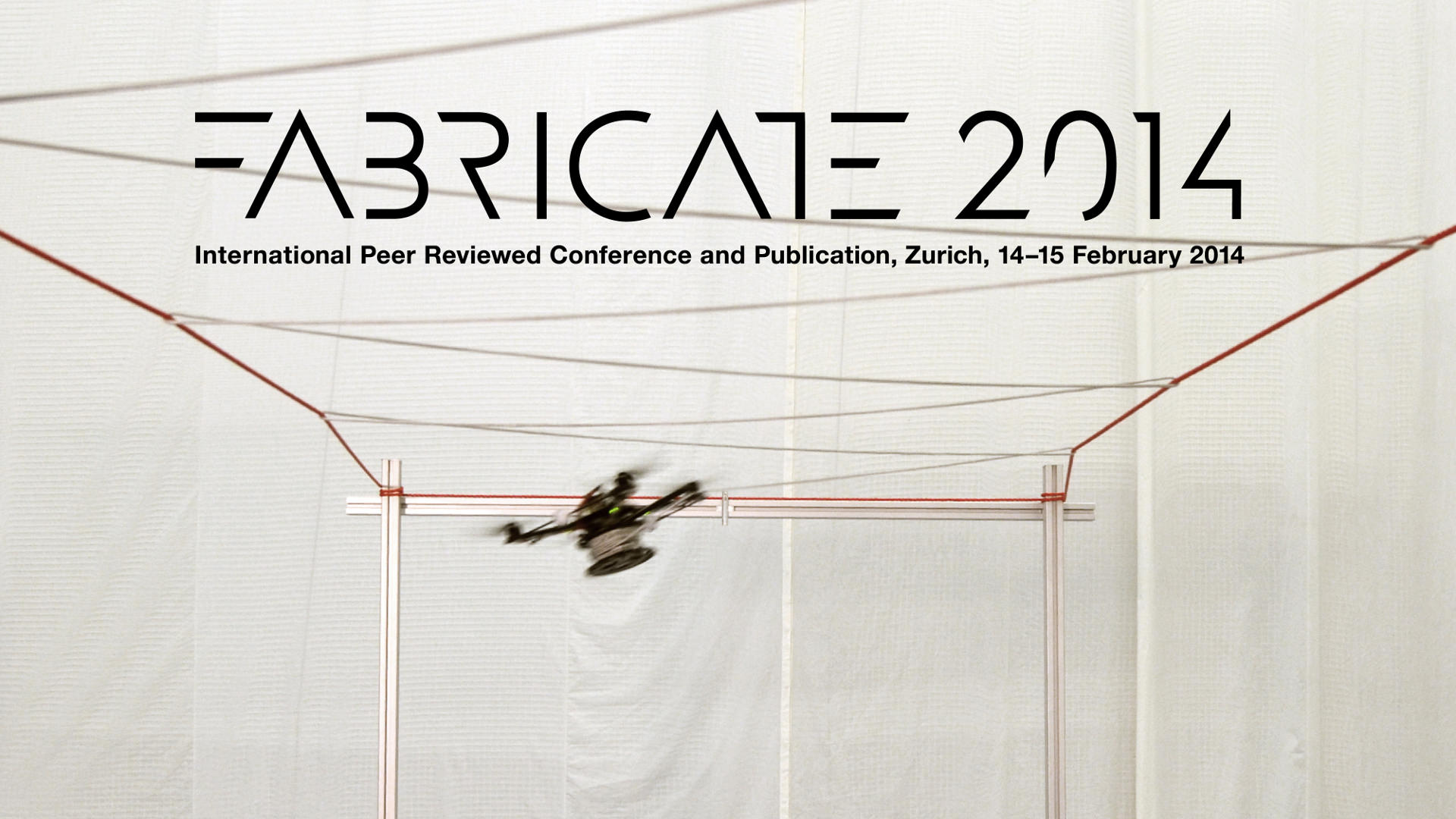

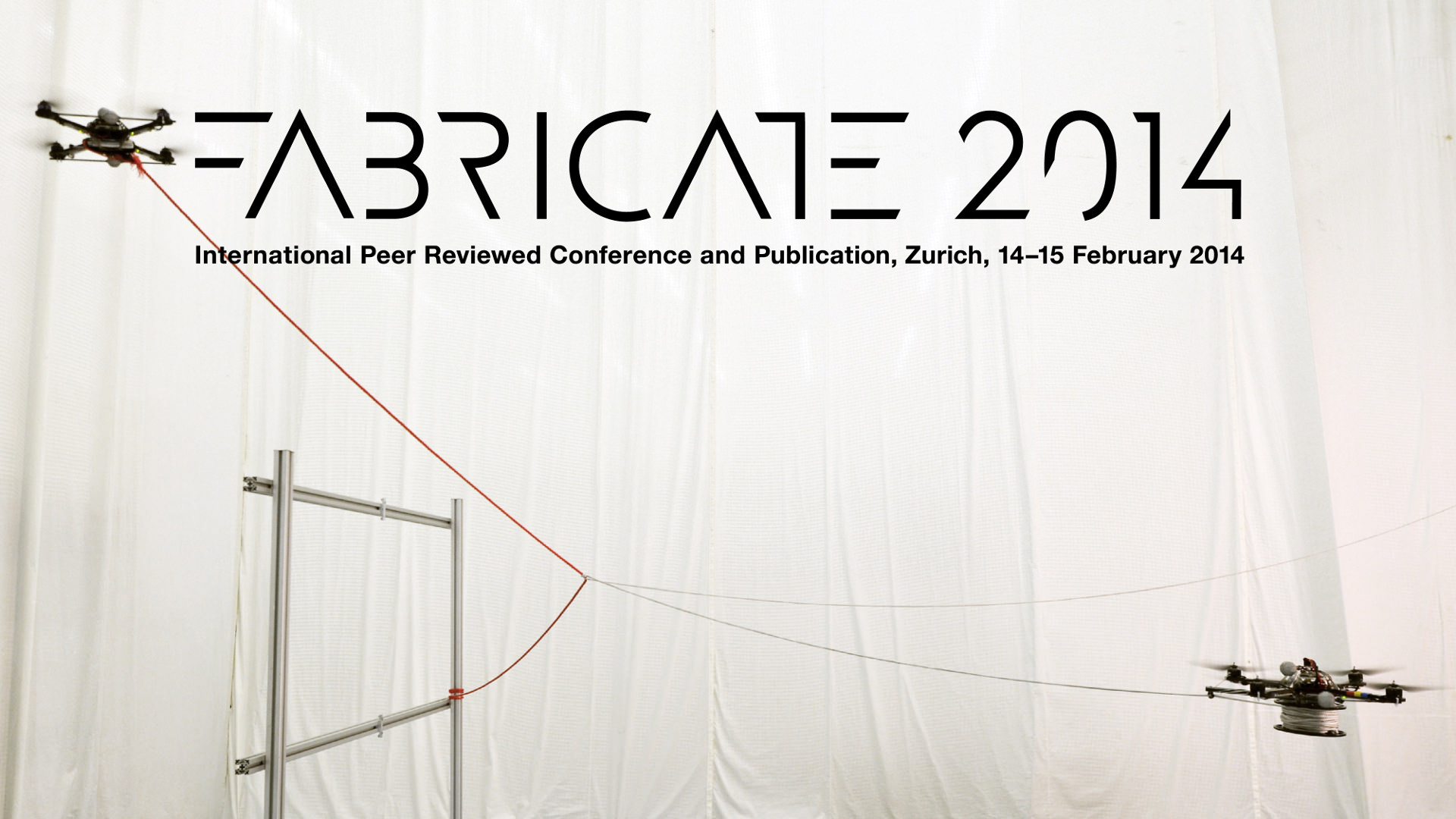

ENOTA was founded in 1998 with the ambition to create contemporary and critical architectural practice of an open type based on a collective approach towards architectural and urban solutions. Over the years ENOTA has served as a creative platform for more than fifty architects, led by founding partners and principal architects Dean Lah and Milan Tomac. ENOTA has received several national and international architecture awards. Their work has been presented on numerous exhibitions and published in professional and broad interest publications all over the world.

![]()

![]()

Ptuj is Slovenia’s oldest city dating back to a settlement from the Stone Age. In the thirteenth century the Dominicans began constructing a monastery and a church bordering existing Romanesque buildings near the city walls. Whilst the monastery was completed in Baroque style, many of the interim Medieval Gothic structures are preserved as well. After serving variously as barracks, a hospital, a museum, and even social housing, its current incarnation as a performance centre has required dancing around all sorts of archaeological considerations on the part of the architects ENOTA. Their solution was to build a building within the building, a set of black contrasting forms which float within the original structure – sharing the space without seeming to actually touch one another.

![]() (ew)

(ew) ![]()

-

DANS arhitekti was founded in 2004 by Rok Bogataj, Miha Dešman, Eva Fišer Berlot, Vlatka Ljubanović, and Katarina Pirkmajer Dešman. Their approach focuses on architecture that fosters social contacts, acts therapeutically, improves living culture and expands the imagination. Their architecture originates from the reflection of the physical, social, and symbolic context of the location. DANS arhitekti are most fond of projects with a salient social dimension, such as schools, kindergartens, hospitals, buildings for people with special needs, and in recent years, they have been engaged in the realm of sacral architecture.

![]()

Architect: DANS arhitekti

Location: Sava River, Bohinjska Bistrica

Client: The Municipality of Bohinj

Date: 2013This wooden bridge, which crosses the Sava River, is part of a cycle path connecting Bohinjska village with nearby Bohinj Lake. The bridge’s form, structure, and materials were carefully chosen to complement the surrounding environment. While the width and slope of the bridge provides room for cycling, its slim design resting on two V-shaped concrete piers accommodates the fluctuating water levels and flow between the seasons. The footbridge's two timber girders are clad with larch boards and shingles, materials recalling traditional methods used for architectural cladding and protection in the region. (ssl)

Photo: Miran Kambič, courtesy DANS arhitekti.

-

![]()

Photo and video by Miran Kambič, courtesy DANS arhitekti.

-

Nobody

Loves

the Hitler

BeetleInterview with Jasmina Cibic

by Susie S. Lee

Jasmina Cibic, “Situation Anophthalmus hitleri”, scientific illustrations of Anophthalmus hitleri, 2012. (All images courtesy the artist)

-

Artist Jasmina Cibic standing in her exhibition, “For our Economy and Culture,” representing the Slovenian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2013.

-

Jasmina Cibic is part of a new generation of Slovenian artists. Originally from Ljubljana, educated in Italy and the UK, and now working in London, she expresses a particular sensitivity to the complexities of cultural identity and the politics of display. She talked to Susie S. Lee about concepts of identity and representation.

You directly address many issues of cultural identity in your work. With Slovenia’s complex political history, how important a role do you feel cultural identity has in Slovenia today?

Slovenia is a very young country, one that is still trying to understand its history, re-discover and re- or de-brand its myths, select a code of behaviour… basically to design the nation’s dress code so to speak. As such it is incredibly interesting from the point of view of identity politics. The cultural identity of a nation is a complex presence, which is always present, but many times – as a construct – it may be placed into the servitude of the state and soft power and, quite frankly, misrepresented.

Your work addresses a number of symbols of cultural iconography. What is the specific Slovenian issue that you discuss in your work?

All my work is context and site specific, so really Slovenia (as the focus of my investigations) has been specifically featured only within my project that represented the country at the 2013 Venice Biennial that explored the choices behind particular state/national representation. For our Economy and Culture was composed of a variety of elements, which examined modes of exchange, reception and constructions of identity and literally dramatised not only the power paradigms inherent in systems of authority, but also the explicit contradictions present in the transmutation of a national identity from past to present, place to place.

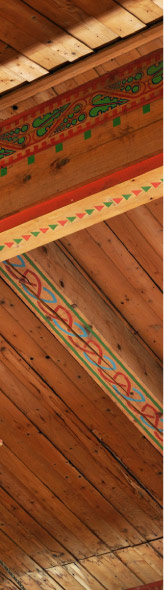

Your Venice installation revolved around the unfortunately-named “Hitler Beetle”. What sparked your interest in this animal?

The project begins with the story of the discovery of one of Slovenia’s endemic species, Anophthalmus hitleri, a cave beetle, which has recently joined the endangered species list solely because of its name. Discovered in 1933 and named by an admirer of Hitler in 1937, this blind beetle marks an un-erasable ideological moment since, according to the rules of Linnaean taxonomy, animal and plant names cannot be changed.

-

Jasmina Cibic, “Ideologies of Display (Dama dama)”, lambda print, 2008.

-

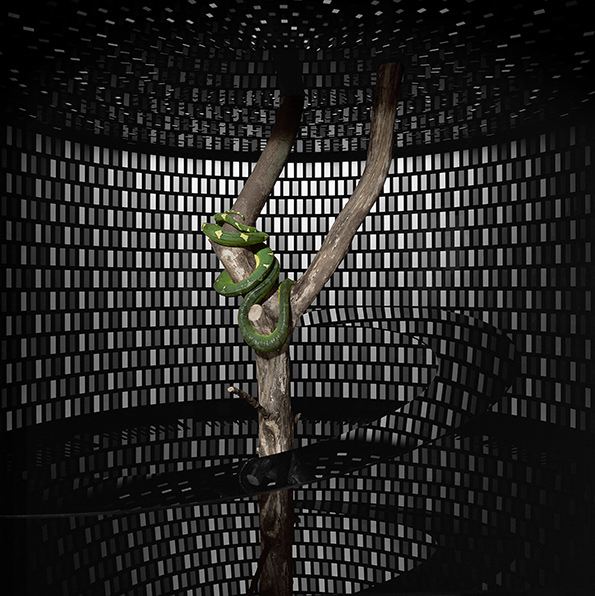

![]()

Jasmina Cibic, “Ideologies of Display (Tyto alba)”, lambda print, 2008.

![]()

Jasmina Cibic, “Ideologies of Display (Corallus caninus)”, lambda print, 2008.

-

Jasmina Cibic, “Ideologies of Display (Vulpes lagopus)”, lambda print, 2008.

-

In 2006, National Geographic Magazine published an article on the insect (in its specific overtly-dramatised tone) and soon after collectors of Nazi memorabilia began to hunt the hitleri down, resulting in this small blind creature coming close to extinction. I worked with over forty international entomologists and scientific illustrators, including associates of The Natural Museum in London, the US Department of Agriculture, the Zoological Museum at Tel Aviv University to produce illustrations of the hitleri beetle.

You called this beetle a “failed national icon”. Do you feel such symbols have had a genuine impact on Slovenian identity or are they not simply constructs?

I speak of the hitleri beetle being a “failed” national icon as its name prohibits (for obvious reasons) it being ever placed on the pedestal of national representation. Cave animals are one of the specifics of Slovenia (the first ever cave beetle was discovered in the country in the late 1800s) and as it is usual with national branding – representatives of endemic and indigenous flora and fauna are the ones that feature on items such as coins, banknotes, stamps, passports etc. As such, of course these symbols are all constructs, but it is precisely the question of when these constructs have a genuine effect on national identity, and if so, is it a positive or a negative one. Within the current state of affairs with upheavals of nationalism I believe it is a crucial question also.

In your work you have built many architectural spaces, some of which only appear in photographs, and you have also referred to the “re-appropriation of modernist architecture”. What is your relationship to architecture and what is the significance of appropriating it in your work?

Within the last decade we have seen a vast resurgence of interest in modernist architecture by fine artists and the former East’s socialist modernism seems to be at the forefront. What is interesting is that we are speaking of a period in architecture’s history that has not been properly presented to the public by the architectural historians (we now finally have the fabulous book Unfinished Modernisations that plots the story of post Second World War Yugoslavia’s architectural plight) – but was initially presented through the fine artists working with it.

![]()

-

Jasmina Cibic was born in Ljubljana, Slovenia in 1979, and is currently based in London. She graduated from the Accademia di Belle Arti in Venice, Italy in 2003 and completed her MA in Fine Art at Goldsmiths College in London in 2006. In 2013, she represented the Slovenian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale with her exhibition, “For our Economy and Culture”. Her work, although acutely conscious of a specific national political, cultural and artistic lineage creates a very distinctive language of its own. Her work is generally site and context specific, performative in nature employing a range of activities, media and theatrical tactics to redefine or reconsider an existent environment or space.

In a way this was a kind of kidnapping of the model and it is quite unprecedented and extremely interesting. My work plays with this double game – when meaning of a real-life model is attributed via fiction first.

What impact do you feel has Slovenia‘s political history as a former socialist state had on state vs. commercial spaces, and art and architecture practices in Slovenia in general?

The specificity of Slovenian art history is that it is unsure about how to tackle contemporary art practice. High modernism thrived in Slovenia much longer than it did in Western Europe and consequently the rupture of contemporaneity took much longer to absorb. I am not exactly sure that contemporary art practices are really even included in the existing art lineage. It almost seems as if there were two parallel art canons in Slovenia: the official one, which ends with the dusk of modernism, and the contemporary one that strives to reconstruct its own specific history. The two have not merged yet. Needless to say, the gap between these two lines of historicisation is often blatantly political. I am therefore ambivalent about how my work fits the Slovene art canon, since it is itself unsure about its criteria and parameters. But I am interested in exploring its paradoxes, which provide a privileged insight into the political mechanisms it operates under. p

In Jasmina Cibic's spatial construction, "Other Mythologies" (2008) a gallery space becomes a poetic reconstruction of a transitory space/waiting room/airport terminal.

-

Repeat

OffendersVid Zabel and Katarina Čakš from the architecture magazine Praznine revisit Slovenia’s homegrown Brutalism

Stanko Kristl's Mladi Rod Kindergarten in Ljubljana, 1969. (Photo: Janez Kališnik, courtesy Stanko Kristl archive)

-

Praznine is a magazine that deals with critical thought and theory in the areas of spatial planning, architecture and art. The magazine involves a younger generation of Slovenian architects, artist and philosophers into critical reevaluation and constant rethinking of the role of architecture and arts in the modern day society. It was established in 2011 by students and graduates of architecture but has since developed a broad span of writers, editors and collaborators from areas of architecture, philosophy, visual arts, design, social sciences, graphics and the humanities.

Katarina Čakš and Vid Zabel are currently finishing their studies at Ljubljana Faculty of Architecture. They co-founded Praznine in 2011 together with Tomo Stanič, Martin Kruh, Rok Velikonja, Barbara Logar, Maša Ogrin and Andreja Žumer

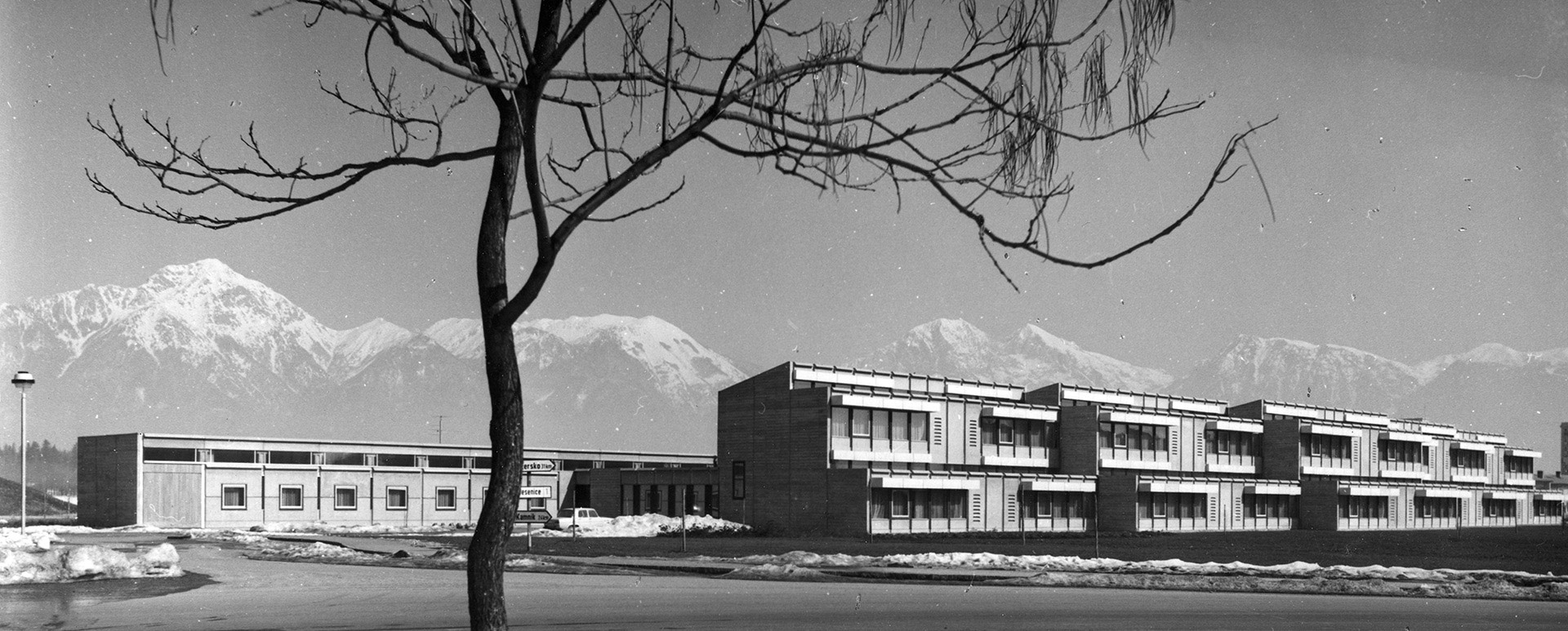

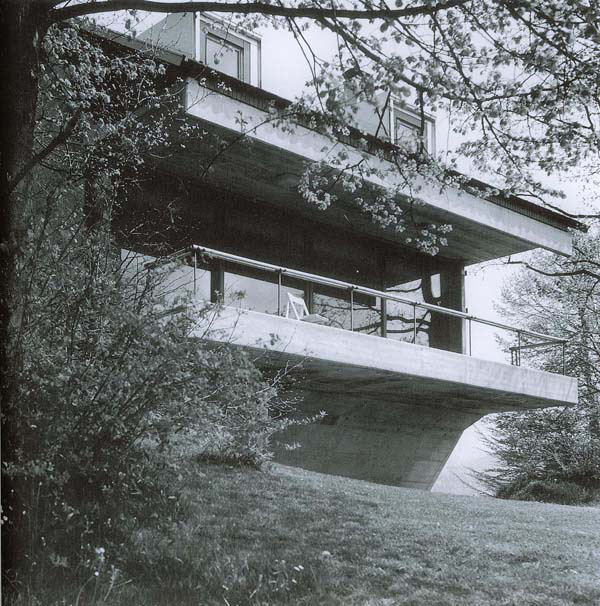

The post-second world war period was a time of distinct formation of Slovenian architecture. In the 1960s whilst the world was moving away from local and regional architectural features, a generation of Slovenian architects began developing their own distinctive approach towards spatial construction. This was as much a consequence of the cultural, economical and political context of the (then) developing Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia as the influence and teachings of the architect Edvard Ravnikar (and through him his mentors Jože Plečnik and Le Corbusier).

In a country that was still building its identity, the architects of the time needed to face the challenge of moderate material resources to serve a society that was in great need of infrastructure. All this, combined with a sense of building in a time of technological and industrial advancement, inspired projects that were particularly ingenious both in terms of technology and spatial ideas. There was a common notion underlying many buildings of the time – an idea of rationality bound together with existentialism.

In the following decades, the continuity of architectural education and mentorship began to disperse as most architecture graduates went on to gain additional experience and knowledge abroad. Nevertheless, the Slovenian architecture of the 1960s and 1970s, with its merging of the universal and the specific through tectonics, materiality and spatial concepts, has become a topical issue once again for a number of contemporary Slovenian architects and teachers. This association is especially apparent in the contemporary use of construction materials and technical innovations as means of defining clear theoretical concepts. -

![]()

Stanko Kristl's France Prešeren Primary School in Kranj, 1965. (Photo: Janez Kališnik, courtesy Stanko Kristl archive)

-

Savin Sever's Mladinska Knjiga Printing House in Ljubljana, 1963. (Photo: Janez Kališnik, courtesy Savin Sever archive)

-

![]()

![]()

Oton Jugovec's Holiday Houses in Zasip, 1972. (Photos: Janez Kališnik, courtesy Oton Jugovec archive)

-

Stanko Kristl's France Prešeren Primary School in Kranj, 1965. (Photo: Janez Kališnik, courtesy Stanko Kristl archive)

-

![]()

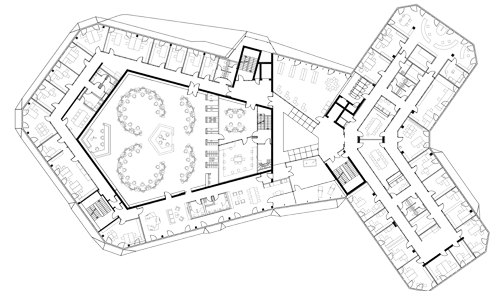

Architect: Sadar + Vuga

Location: Ljubljana

Client: Slovenia Control, Slovenian Air Navigation Services Ltd.

Date: 2013Photo: Miran Kambič, courtesy Sadar + Vuga

-

Sadar + Vuga, founded by Jurij Sadar and Boštjan Vuga in Ljubljana in 1996, focuses on open, innovative and integral architectural design and urban planning. Projects have included the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Slovenia, which received the Bauwelt Prize (2001); the new entrance hall for the National Gallery of Slovenia; the Mercator Shopping center; housing projects Condominium Trnovski pristan and House Gradaška, all recipients of prizes and nominations for the Mies van der Rohe Awards. Recent projects have included the Sports Park Stožice in Ljubljana, combining a football stadium with a multi-purpose sports hall and recreational park; a new air traffic control centre at Ljubljana airport, as well as the Cultural Center of EU Space Technologies in Vitanje, Slovenia. Current projects include a new building for the Study of Social Work as well as a sports hall extension, both at the Campus of University College Ghent in Belgium.

![]()

Nature reflected in the bronze windows. (Photo: David Lotrič, courtesy Sadar + Vuga)Air traffic control is a stressful, 24/7 business and requires a building that can combine comfort with security. The newly completed ATCC in Ljubljana is divided into a pentagonal head (control centre) and a pair of wings (offices and public programmes), with the lobby, restaurant, conference rooms and gymnasium situated between the two. The building is organised into five security zones: the further one moves from the rim (administrative and rest areas) towards the building’s core, the greater the security level. The bronze reflective glass windows mirror the surrounding nature and airplanes, making them part of the building’s design.

![]() (fh)

(fh)![]()

First Floor Plan. (Image: Sadar + Vuga) -

![]()

Renovation of the Breg Embankment by Atelje Vozlič. (All photos: Miran Kambič)

Buy Me a River

The renovation of the River Ljubljanica

Maša Ogrin

Between 2004 and 2011 Ljubljana invested 20 million euros in stimulating its inner city revival by renovating the embankments along the River Ljubljanica. The project includes a series of public structures and spaces including bridges, parks, a pavilion and a floating pier, designed by several architectural offices that build on Jože Plečnik’s inspired designs from the 1930s. Ljubljana has a long history of engagement with its water: 5,000-year old pile–dwellings on nearby Ljubljana marshes make it one of the first European cities to utilise bridge technology. However, up until Plečnik, the city’s attitude towards its river was to use it, not respect it.

![]()

-

Maša Ogrin, a graduate of the Faculty of Architecture in Ljubljana, has worked on architecture and design projects across Europe. Her last major design project was Pop-up dom currently in Venice, focusing international attention on the young Slovenian design scene. For several years she has been an editor of Trajekt.org, a portal on spatial culture in Slovenia, and is one of the initiators of architectural magazine Praznine which was nominated for Plečnik’s medal.

![]()

Plečnik’s “beach” along the river.Plečnik’s vision for the city, as a sequence of urban parterres with multipurpose usages, promenades, city streets and squares also included consideration of the river embankments and bridges. His walkways fly from river level to embankment and vice versa, enriching the cityscape. Now Plečnik’s bridges such as the Čevljarski Most (Cobblers’ Bridge) have been joined by new ones like Mesarski Most (Butchers’ Bridge), which was designed by Atelier Arhitekti, lending spacious urban “living rooms” to an otherwise dense city centre and complementing generous spatial interventions on the banks, such as Plečnik’s ensemble of arcades and double height market. The new Fabiani Bridge completes the inner-ring road around Ljubljana and at the same time draws pedestrians down to the river level.

Public spaces such the Breg embankment, with its auditorium on the river and a new street market held nearby, and the cascaded form of the new urban Park Špica, also designed by Atelier Arhitekti at the spike of Ljubljana Island, augment Plečniks’ Trnovski Pristan embankment, known as “Ljubljana beach”. In contrast to the narrow foot-passages such as Gledališka Stolba (Theatre staircase) and Ključavničarska ulica (Locksmith Street) this renovation scheme emphasises the original tight medieval street pattern, lending a dynamic tension to the urban fabric of the city.![]()

![]()

The renovated “Triple Bridge”: Plečnik added the two pedestrian side bridges in the 1930s. -

Sylvan

StructuresRok Oman and Špela Videčnik of OFIS arhitekti on their love affair with wood

Farewell Chapel was completed by OFIS in 2009 in Krasnja, a village close to Ljubljana. (Photo: Tomaž Gregorič, courtesy OFIS)

-

Slovenia is a land of forests. Even today they cover almost 60 percent of the country. Being such a versatile building material, wood has been widely used in the country for millennia to create living spaces. The first known wooden structures in Slovenia date from 4,600 years BCE. These were pile dwellings — clusters of houses sharing a wooden platform on wooden piles constructed above water, such as those found in the Ljubljansko barje, the marshes near Ljubljana.

The structural limitations of wood — in beams, arches, piles or columns — has been continually tested, with methods of construction honed down to rational and logical ones that use simple shapes and forms such as squares, triangles and diagonals.![]()

The church of St. Michael, Crna Vas, 1937-1940, is one of Plečnik’s most original creations, yet is built on wooden piles in traditional Slovenian fashion. (Photo: Miran Kambič)

![]()

Shopping Roof Apartments in Bohinjska Bistrica by OFIS. (Photo: Tomaž Gregorič, courtesy OFIS)

-

Analysis of traditional timber structures shows that their geometric order is often defined by the golden section, closest to humanity’s concept of beauty, and perhaps for this reason they often appear in harmony with nature and their surroundings.

A classic Slovenian example of this are traditional hayracks. One cannot travel far in the Slovenian countryside before coming across these wooden drying racks that dot the fields. They are used during the summer months to make hay from the soft meadow grasses, whilst in autumn, the wind blowing through their struts dries the beans and maize. In particular, the beautiful toplarji double hayracks, with their storage lofts and roofs, are unique to Slovenia, many built in the seventeenth century from oak and beech with carefully shaped and carved beams.

In the twentieth century, Jože Plečnik’s wooden church in Crna Vas, near Ljubljana, reinvented the use of constructional timber by drawing on folk traditions and styles. As the son of a carpenter, Plečnik always had great respect for and deep knowledge of the material.![]()

Wood interior of Villa Under Extension in Bled by OFIS, 2005. (Photo: Tomaž Gregorič, courtesy OFIS)

![]()

-

Hayracks are a characteristic element of the central Slovenian countryside, utilitarian structures whose construction details, distinctive proportions and ornamentation are important examples of Slovenian vernacular architecture. They reflects the specific ethnic culture of a territory that was a meeting point for Mediterranean (Roman), middle-European and Pannonian civilisations. (Photo: Miran Kambič)

-

![]()

The Hayrack Apartments by OFIS are a social housing block on Ljubljana’s outskirts, their façade referencing typical Slovenian hayracks. (Photo: Tomaž Gregorič, courtesy OFIS)

-

OFIS arhitekti was established in 1996 in Ljubljana by Rok Oman and Špela Videčnik, on the back of winning several competitions including the Football Stadium Maribor and the Ljubljana City Museum extension and renovation. In 2000 they won the “Young Architect of the Year” award in London, UK, and since then their projects have been nominated for awards, including the Mies van der Rohe Award. The company works internationally, and projects have included a business complex in Venice Marghera, Italy, a residential complex in Graz, Austria, as well as 180 apartments in Petit Ponts, Paris, a project which led to the opening of a branch office in France, 2007. Most recently they completed a football stadium for FC BATE in Borisov, Belarus. Both partners teach at Harvard in the USA.

In the past decade, wood in Slovenian architecture and design has been experiencing a renaissance. Innovative timber construction systems have resulted in architects and clients rediscovering wood’s excellent ecological characteristics, fast and simple construction, and the attractive living environment it can create.

For us at OFIS, wood offers the chance to explore a unique national language as a counterbalance to fashionable globalised architecture. In projects such as the Shopping Roof Apartments (2007) we explored and reinvented traditional ways of using the material, with wooden elements forming façade cladding, balcony balustrade, roof, snow protection, and rain drainage, creating platforms and terraces, whilst with the Hayrack Apartments (2007) we paid tribute to traditional folk designs. We also use wood in all kinds of interior projects, such as the Villa Under Extension (2008). A wooden interior is cosy, elegant and friendly, creating a good acoustic and fragrant ambience.

For low cost housing we’ve explored highly pressed wooden laminates to form a wide range of façade claddings, balcony and terrace fences, side shelters, roofs, pergolas, which are durable and affordable. We’ve used these in urban and suburban contexts in Ljubljana, at the coast (the Honeycomb Apartments, 2006), as well as recently in Paris, at the Basket Apartments (2012).![]()

OFIS completed their well-known Honeycomb Apartments in Izola Bay in 2006. The buildings were the result of a competition by the Slovenia Housing Fund and provide low-cost homes for families. (Photo: Tomaž Gregorič, courtesy OFIS)

-

In the Photo Booth with ...

Sou Fujimoto

Sou Fujimoto is not only famous, but really well-liked, as evidenced by the endless line of students and fans waiting to meet him (or even snap a selfie with him) after his recent lecture at Berlin’s Technical University. uncube invited him to our own version of the selfie: our photobooth.

Interview by Stephan Becker and Luise Rellensmann

![]()

-

The auditorium was unbelievably crowded tonight, reflecting the great European enthusiasm for Japanese architecture these days. How has this increased interest been perceived in Japan?

I’m very happy to see so many people interested in Japanese architecture. I really don’t know why our architecture is of such interest to so many people in Europe, but its popularity is certainly down to the work of architects like Toyo Ito and Kazujo Sejima of SANAA. They’ve opened a big door for us – the next generation. I feel it’s my responsibility to hold that door open.

-

Do you think there is anything characteristically Japanese about your architecture or in your approach to building?

My work is very much about in between things. This ambiguity is very Japanese. I want to create work between nature and architecture, building something that is beyond both. But I have a very open understanding of Japanese tradition, and like to be influenced by architecture from anywhere.

Japanese and European architecture aren’t completely separated anyway – all architecture is developed for people to live in and use. I am enjoying the challenge of combining traditions now in Bielefeld, Germany where we’re about to start building an extension to Philip Johnson’s Kunsthalle, a really interesting building. I want to keep exploring what is possible within and through architecture in different climates and cultures.

-

Born in Hokkaido in 1971, Sou Fujimoto graduated from the University of Tokyo in 1994, and established his own office, Sou Fujimoto Architects, in 2000. Noted for delicate, light structures and permeable enclosures, Fujimoto has so far completed the majority of his buildings in Japan, with commissions ranging from the domestic, such as Final Wooden House, T House and House N, to the institutional, such as the Musashino Art Museum and Library at Musashino Art University. In 2013, he was selected to design the temporary Serpentine Gallery pavilion in London and the extension to the Kunsthalle Bielefeld in Germany.

Your idea of the city as a forest, and of introducing small patches of greenery into it like clearings, comes out of looking at the urban fabric of Tokyo. Does this metaphor for a city translate to somewhere like Berlin?

Compared to Asian cities, the major infrastructional elements of European cities like Berlin or Paris are very large and complex, which does not allow for the same type of penetration of nature. But human activity still centres around smaller scale spaces like cafés. In every culture it is the elements based on human scale that create the urban fabric.

![]()

-

Pro qm is a thematic bookstore in Berlin-Mitte, founded in 1999. The emphasis is on the urban and its links to politics, pop culture, economic critique, architecture, design, art, and related issues. The bookshop holds frequent events at its location and contributes to exhibitions and conferences. Since its foundation Pro qm has established itself internationally as a specialised bookstore and venue for interdisciplinary debates concerning the city, architectural theory and artistic practice.

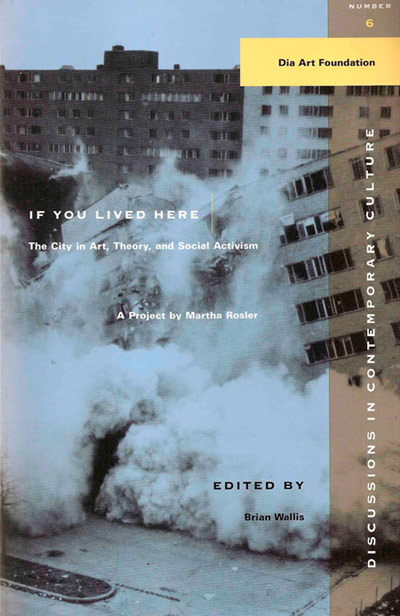

If You Lived Here.

The City in Art, Theory, and Social Activism.

A Project by Martha Rosler.

Edited by Brian Wallis.

Paperback, 312 pp., 22.2 x 15 cm

ISBN-10: 1565844988

New Press, 1998

![]()

In the second of our occasional series of guest book reviews, the specialists at Berlin bookstore Pro qm have opened up their treasure chest of all-time favourites. Unsurprisingly for a store loaded with historical and theoretical tomes on urbanism, their selection includes some must-reads in politically aware planning theory, yet they’ve also included a website – hey, the internet is no threat to paper: just a means to print your own books!

If You Lived Here is a publication that accompanied a series of events and exhibitions in New York organised by Martha Rosler in 1989. It brought together artists, activists, planners, scientists, residents and neighbours, documenting the crisis in New York’s housing market in the late 1980s, while also presenting a broad range of analysis and strategies to counteract the situation. Dealing with town planning, gentrification, housing and homelessness, this a surefire classic on how artists engage in social urban topics, including the ambivalent relationship between art, artists, and processes of gentrification – and a history of homelessness in the US to boot.

![]()

-

Let’s Re-make! : Access to Tools

(formerly known as The Library of Radiant Optimism)

by Bonnie Fortune and Brett Bloom

![]()

Let’s Re-make! is a website run by Bonnie Fortune and Brett Bloom that serves as an archive for countercultural books from the late 60s and early 70s. You’ll find seminal publications like How To Build Your Own Living Structures (1974), Garbage Housing (1975) by Martin Pawley, and Nomadic Furniture (1973) by Victor Papanek. As they explain, all the publications “shared the aesthetic and ethics of self-publication and self-education” and document everything from “communal living spaces and growing your own organic garden to early sustainable design initiatives and home-birthing... [paving] the way for today’s environmental movement and sustainable design culture.” There’s nothing to add… let’s re-make!

![]()

-

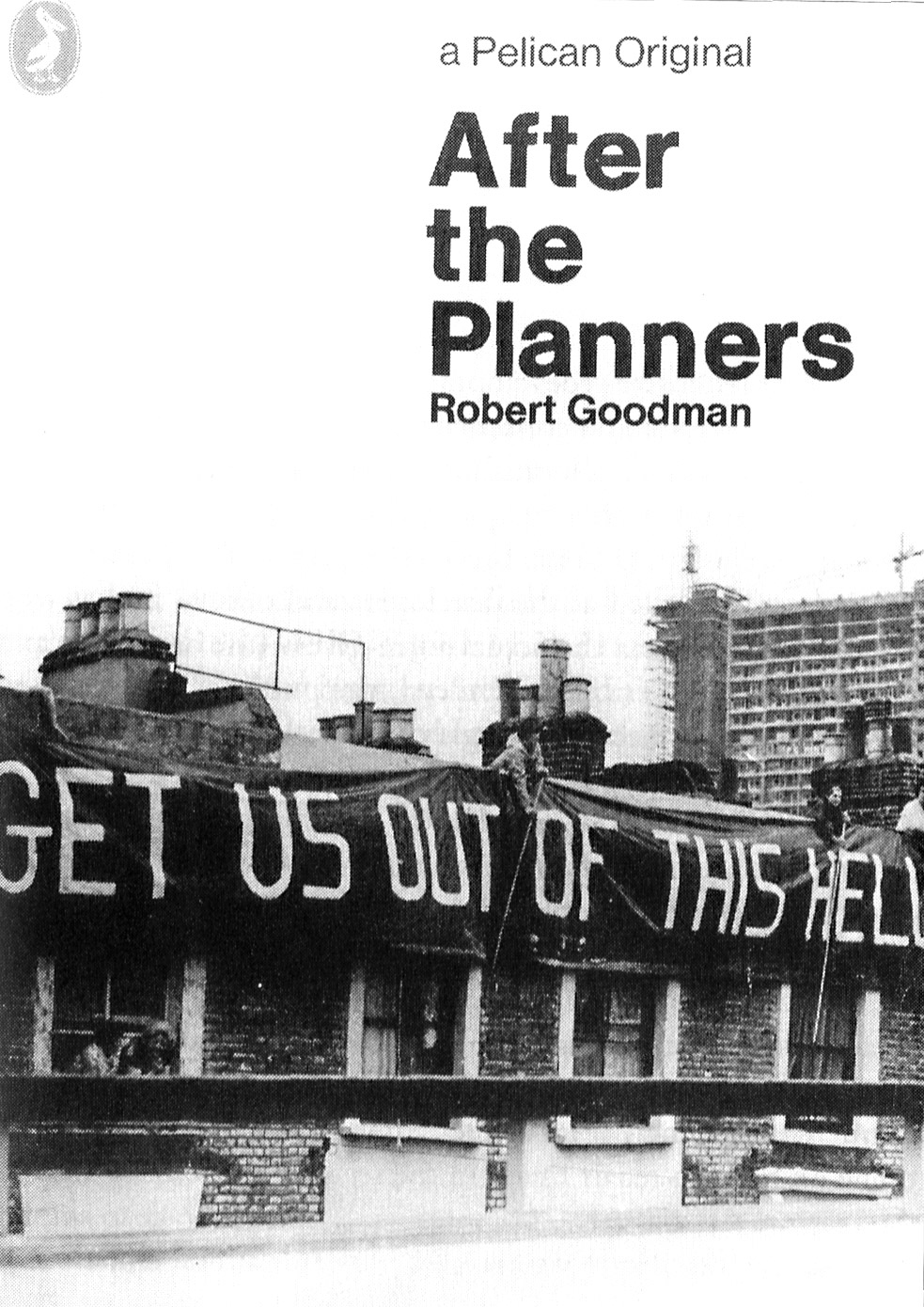

After the Planners

by Robert Goodman

Paperback, 272pp., 19.6 x 12.8 cm

ISBN-10: 0140215689

Penguin Books, New York, 1972

![]()

When he wrote After the Planners, advocacy planner Robert Goodman had spent years fighting official plans to revitalise the city of Boston via eight-lane highways cutting through existing neighbourhoods, which would cause thousands to lose their homes. Goodman, working with the independent Urban Planning Aid group, helped develop alternative planning methods that would let concerned people participate. Goodman believed planners needed to fundamentally change the way they understood their profession, comparing their current role to that of the police or military. The strategy of “guerilla architecture” that he proposed in this book was intended to sharpen people’s consciousness of their own power to deal with their (urban) surroundings, and makes this book useful and surprisingly contemporary.

![]()

-

Lucius Burckhardt Writings

Rethinking Man-made Environments: Politics, Landscape & Design

Edited by Jesko Fezer and Marin Schmitz

Birkhauser/Springer, 2012

Paperback, 288 pages, 19 x 13.2 cm

ISBN-10: 3709112567

![]()

![]()

This first English translation of Lucius Burckhardt’s key essays provides an introduction to the timeless thinking of the Swiss political economist, sociologist, art historian, planning theorist — and founding father of the science of strollology (strolling)! Burckhardt (1925–2003) was a pioneer of interdisciplinary analysis of the human-made environment. He was bold: claiming design should be invisible; exasperating: asking why landscape is beautiful; egalitarian: addressing the “livability” of everyday life; provocative: focusing on concepts like “the night” and “dirt”; rebellious: making a science out of taking a stroll; and far-sighted: claiming that care and maintenance are destructive.

![]()

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Form follows feminine.«

Oscar Niemeyer

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents