-

Magazine No. 22

Water

-

No. 22 - Water

-

page 02

Cover

Water

-

page 03

Editorial

Water

-

page 05 - 08

Adriaport

Czechoslovakia's 1970s plan to build a tunnel to the sea

-

page 09

China on Ice

Harbin Ice and Snow Festival

-

page 11 - 13

The Trouble with Water I

By Sagel & Krzykowski

-

page 14 - 17

Tropical Island

A Big Brandenburg Oasis

-

page 19

Dam it All

Hoover Dam and beyond

-

page 20 - 24

Pink Pipe Dream

Ludwig Leo‘s Umlauftank in Berlin

-

page 25 - 27

The Trouble with Water II

By Sagel & Krzykowski

-

page 28 - 29

Oh Well

Indian Stepwells

-

page 31 - 39

Holding Back the Waves

Climate engineer Matthias Schuler achieves active solutions through passive measures

-

page 40

Lonely as a Cloud

Leandro Ehrlich's Cloud Collection

-

page 41 - 44

Stream Lines

Repurposed Dutch water defenses

-

page 45

Death on the Nile

Watery pleasure dome at Hadrian's Villa

-

page 46 - 51

Underwater Love

Chris Bosse on water, nature and Frei Otto

-

page 52 - 54

The Trouble with Water III

By Sagel & Krzykowski

-

page 55

Ooho

The edible water bottle

-

page 56 - 57

Kraftwerk Artwork

Hydroelectric power station in Germany

-

page 58 - 59

Bookmarked

The Drinkable Book

-

page 60

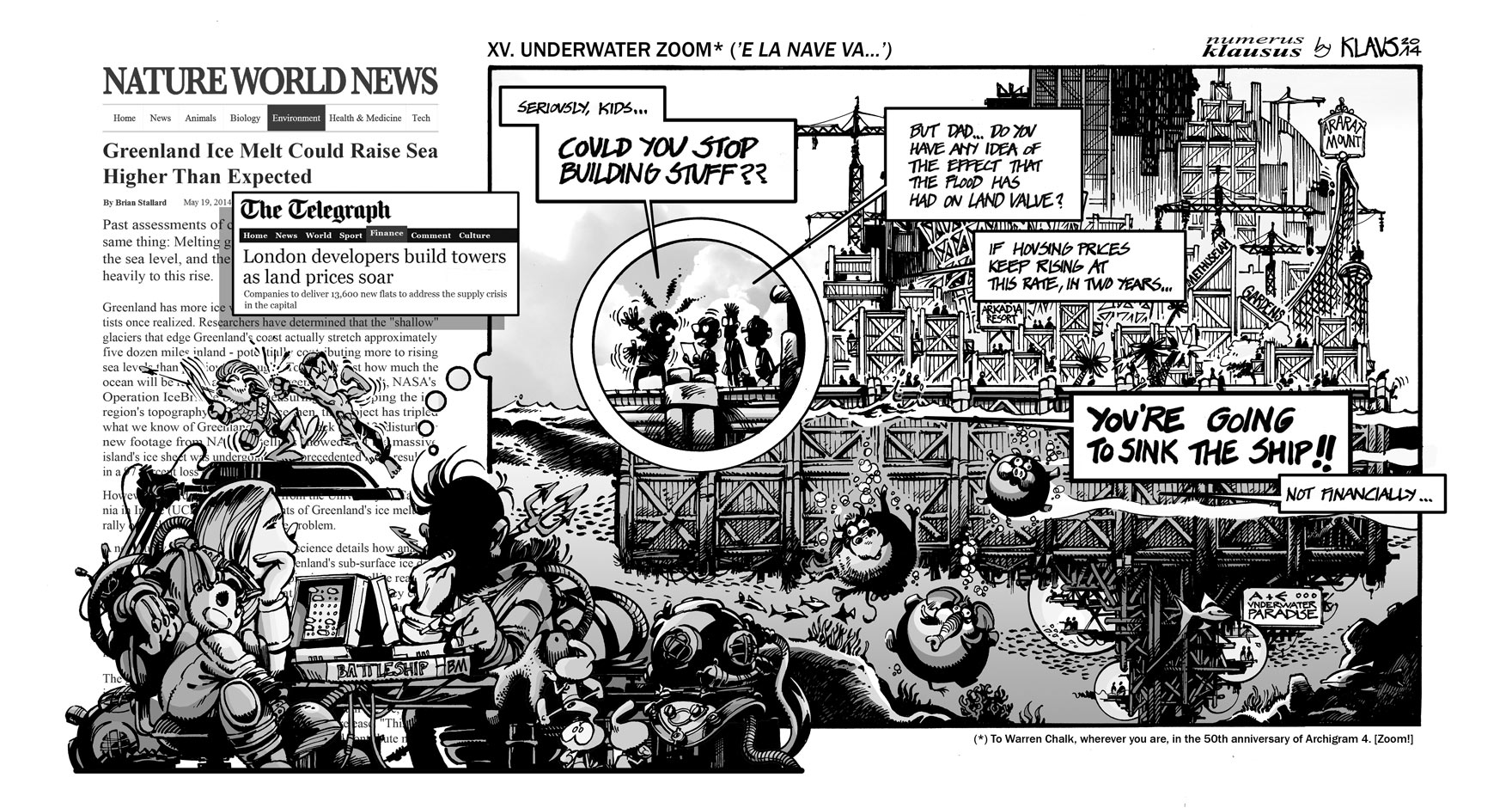

Klaustoon

XV. Underwater Zoom* ('e la nave va...')

-

page 61

Next

Mexico City

-

-

uncube's editors are Sophie Lovell (Art Director, Editor-in-Chief), Florian Heilmeyer, Rob Wilson and Elvia Wilk; editorial assistance: Susie S. Lee and Leigh Theodore Vlassis; graphic design: Lena Giavanazzi; graphics assistance: Madalena Guerra. uncube is based in Berlin and is published by BauNetz, Germany's most-read online magazine covering architecture in a thoughtful way since 1996.

![]()

Given that impending global crises may revolve around water issues, we’ve chosen this pressing moment to focus on our most precious resource. How can water function as a design material? Can architecture shape the future of natural resource management? Will engineers save the planet? All this and more in uncube’s issue no. 22: Water.

Dive in.

Cover image: Edward Burtynsky, “Xiaolangdi Dam #1”, Yellow River, Henan Province, China, 2011. © Edward Burtynsky, courtesy Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Galerie Röpke, Köln / Galerie Springer, Berlin.

-

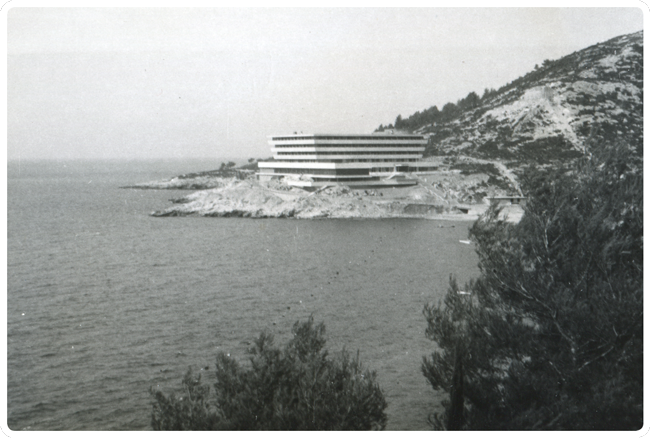

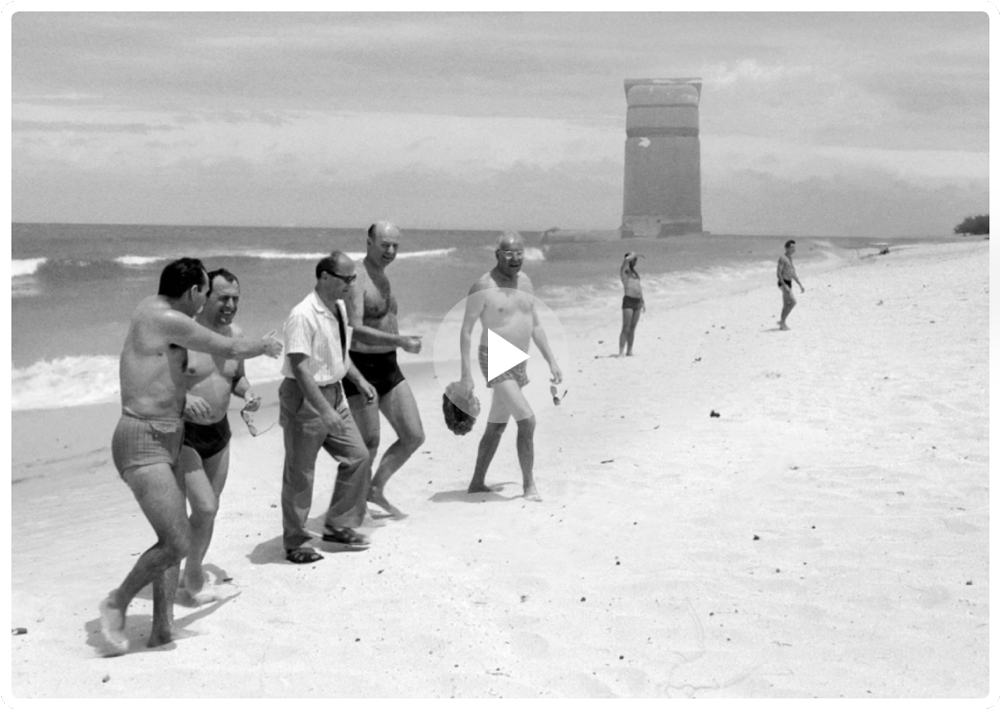

Adriaport

In the 1970s, Czechoslovakia had a plan to build a tunnel to the sea…

by Rob Wilson

-

It is not surprising that landlocked countries might occasionally go stir-crazy dreaming of the sea – wars have started for the want of a good harbour and we all love a sea view. So imagine being a landlocked country in the deep freeze of the Cold War, with an Iron Curtain and a country or two separating you from the nearest beach. This was the situation for those living in then-Czechoslovakia in 1975, when an economics professor, Karel Žlábek, proposed a solution: why not build a tunnel from the Czech border directly to the coast of the Adriatic?

With the help of the engineering company Pragoprojekt, Žlábek produced a detailed design and presented it to the Czech Government.![]()

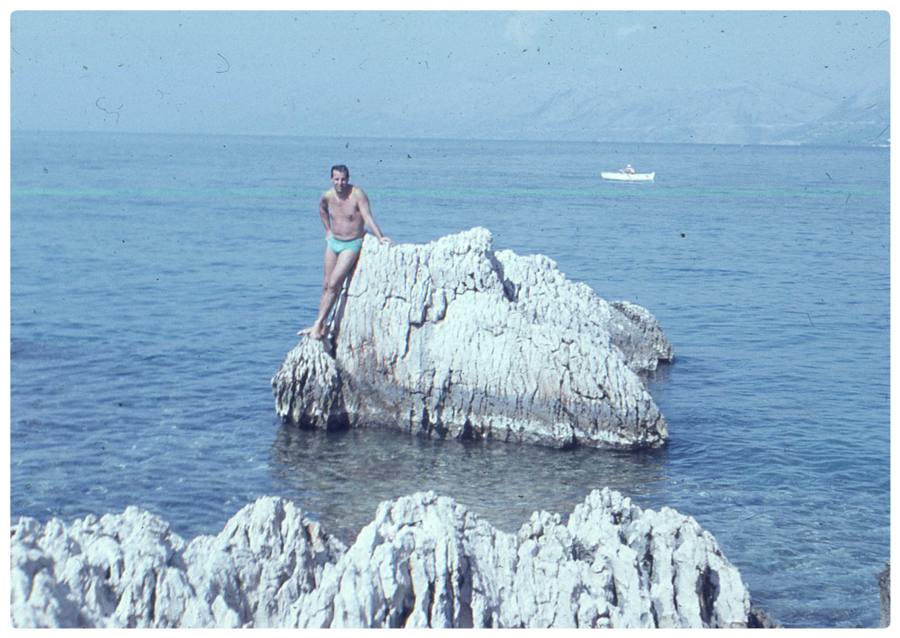

Previous and this page: Vintage photographs, stills from “Return to Adriaport”, 2013. (Photos courtesy Adela Babanova)

Where his proposed tunnel emerged at the coast, its excavated spoil would be used to create an artificial island with a new port for Czechoslovakia, called Adriaport.

The proposal was primarily economic, as it would enable import and export of goods directly to and from the Adriatic, but inevitably it had an emotional bucket-and-spade edge to it as well – allowing dreams of holidays at the seaside, melting ice creams, lobster-red bodies and all.

This is the side that the artist Adela Babanova picked up on in her recent video work Return to Adriaport, which premiered at Loop Art Fair Barcelona in 2013. -

![]()

![]()

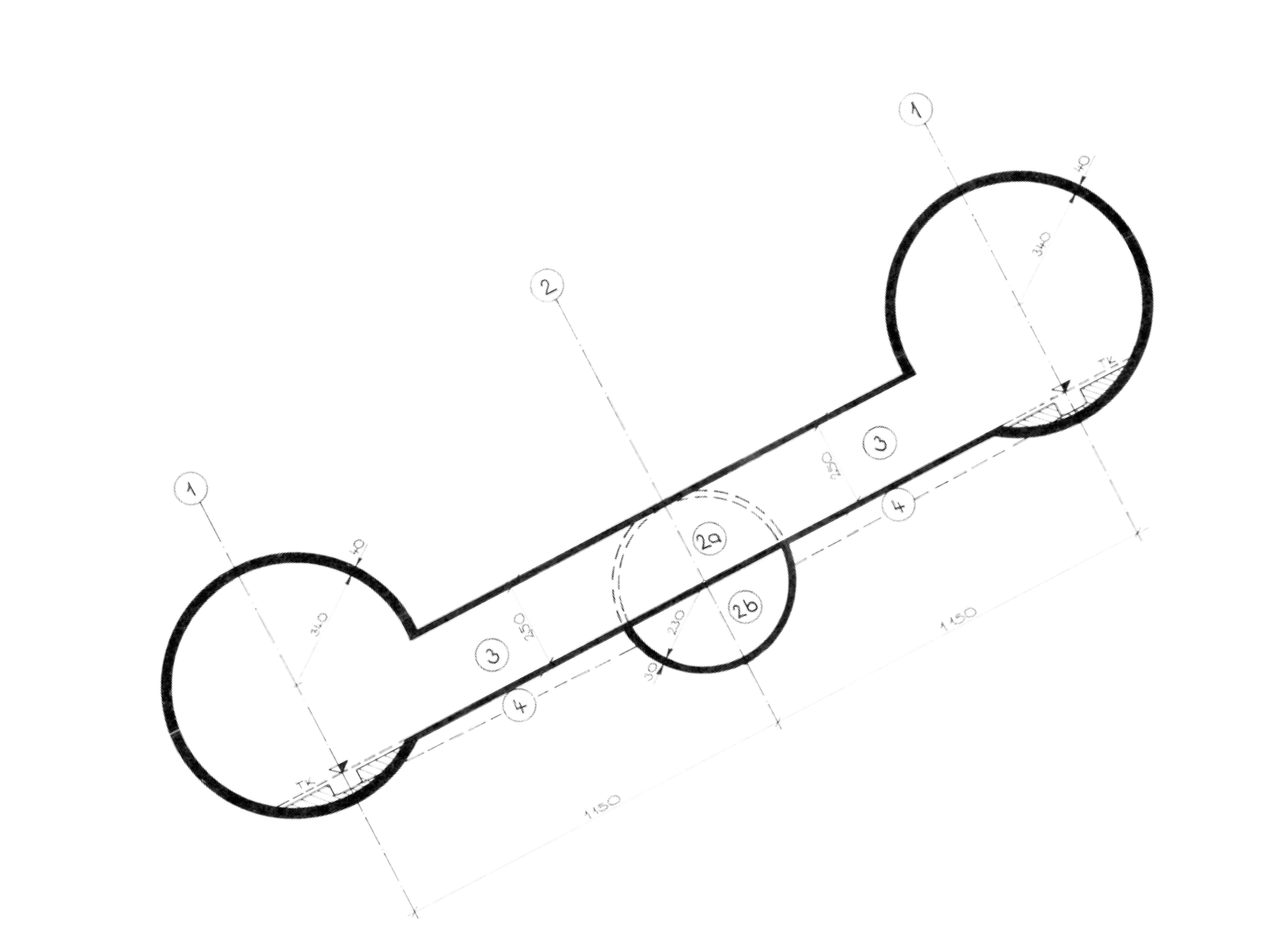

![]()

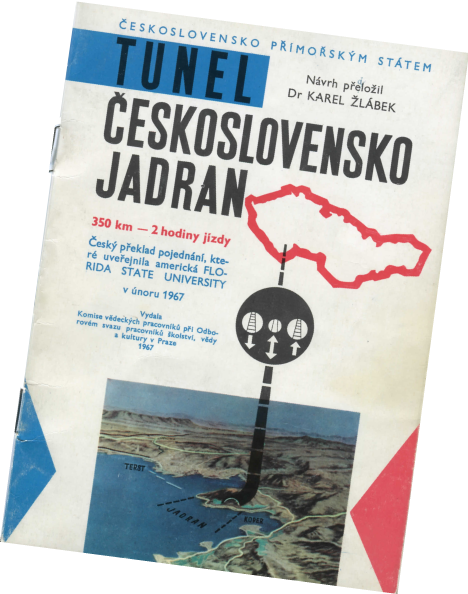

Vintage photographs, stills from “Return to Adriaport”, 2013. (Photos courtesy Adela Babanova). Extract from: “Return to Adriaport”, 2013, directed by Adela Babanova, written by Džian Baban and Vojtěch Mašek. (Video courtesy Adela Babanova). Sectional drawing through the proposed Adriaport tunnel. (Drawing courtesy Pragoproject)

-

In her work Adela Babanova uses literary forms, elements and procedures from radio and television genres such as staged interviews and TV debates. From the beginning of her artistic career she has collaborated with the screenplay-writer duo Vojtěch Mašek and Džian Baban. She teams up with professional film crews and actors, and uses manipulated vintage photography and 3D animation for her stories. Babanova studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague between 2000 and 2006, and in 2011, was finalist in the National Gallery Prague Art Award. In 2012, she was nominated for Jindřich Chalupecký Award.

Return to Adriaport

HD Single channel bluray projection video, PAL, 13 min., 2013

Written by Džian Baban, Vojtěch Mašek; Directed by Adéla Babanová; Camera Jakub Halousek; Edited by Adéla Babanová, Hedvika HansalováSupported by the Ministry of Culture, Czech Republic; Partners: Pragoprojekt, Czech News Agency.

![]()

It takes the form of an imagined documentary, scripted by screenwriters Vojtech Masek and Dzian Baban, using manipulated vintage 1970s photographs and juxtaposed with the original drawings for the tunnel. It reconstructs the meeting that Professor Žlábek had with the Czech President, Gustáv Husák, to convince him of his vision and share dreams of the sea.

Though practical engineering-wise, the project was a pipe-dream geo-politically, not least because the tunnel mainly ran under Austria, a country on the other side of the Iron Curtain. Professor Žlábek continued working on the project until his death in 1984, but his plans ended up in the archives of the Ministry of Interior Affairs, as a small fragment of buried utopia. I (rgw)

![]()

Cover of a 1967 report produced by Professor Karel Žlábek, working with Pragoproject, on the proposed Adriaport tunnel. (Courtesy Pragoproject). Vintage photograph, still from “Return to Adriaport”, 2013. (Photo courtesy Adela Babanova)

-

China on Ice

With winter temperatures often dipping below minus 35 Celsius, and its proximity to Siberia, the Chinese city of Harbin in Heilongjiang Province is the perfect spot for the world’s largest ice and snow festival.

In true Chinese style, the Harbin International Ice and Snow Sculpture Festival goes above and beyond standard superlatives. Each January, a colossal city of actual-sized buildings and sculptures are built from ice, hauled from the nearby Songhua River. At night the whole thing is lit up in a son et lumière spectacle. Attracting 800,000 tourists per year, the festival lasts until the sculptures slowly melt back into the river in spring. I (ltv)Photo: REUTERS/Sheng Li

-

TTwW

Part 1/3

The Trouble with Water

Photographs by Sagel & Krzykowski

Only 3 per cent of the world’s water is fresh water, and two-thirds of that is (for now) locked in frozen glaciers or otherwise unavailable for our use. We need it, we waste it, we spoil it and we fight over it. Christoph Sagel and Matylda Krzykowski’s photoessay reflects a whole sea of troubles but also a few precious drops in the ocean aimed at making things right.

-

Total Meltdown

We have got to the point of not “if” but “when”. Two independent studies, both published in May 2014, reported the unstoppable collapse of a massive ice sheet in the Antarctic prompting conservative predictions of a rise in global sea levels by up to ten feet in the coming 200 years – enough to more than wet the feet of New York, Mumbai and London, not to mention the Maldives, Bangladesh, Venice…

»Today we present observational evidence that a large sector of the West Antarctic ice sheet has gone into irreversible retreat. It has passed the point of no return.«

Dr. Eric Rignot, Professor of Earth System Science, NASA press conference, 12th May 2014 -

Breaking the Waves

Sometimes the forces of nature can be so great that all you can do is run. Recent tsunamis in Japan and Indonesia revealed the devastation that water can cause. While Japan had some of the most sophisticated seismic detection technology known to man, what they lacked was an organised plan of evacuation. In West Sumatra, tsunami evacuation raised earth parks have since been proposed by Geohazards International and others along with clearly marked escape routes from beaches, as a low-cost, locally sourced solution to providing safe areas of elevation for evacuation.

![]()

Video: GeoHazards International.

-

![]()

Tropical Island

All photos courtesy Tropical Islands

-

![]()

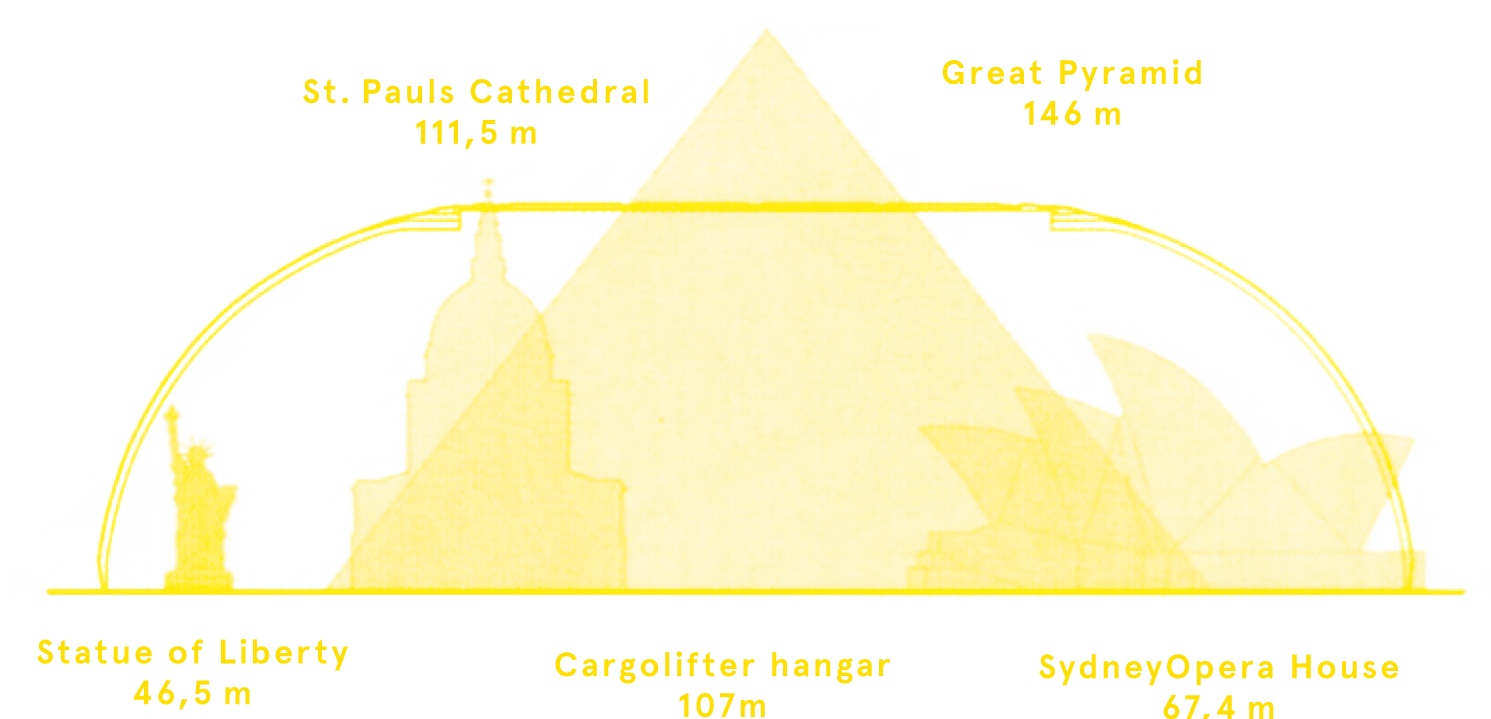

History and ideology still define nearly every spot in and around Berlin, even an otherwise totally inconspicuous plot of land in the middle of the Brandenburg steppe near Krausnick, on the way to Dresden. The shiny silver dome that looms over the landscape here – one of the largest buildings on earth, and the largest single hall without supporting pillars – would most probably never have been built if Nazi Germany had not created an airfield for the Luftwaffe on this site, one later occupied by the Red Army. After reunification and privatisation this humongous hangar, 360 metres long, 210 metres wide and 107 metres high, was built by Cargolifter AG as a hangar for giant airships, intended to transport extremely heavy and outsized loads.

When in 2002 the company went bankrupt without a single giant zeppelin ever being built, the 5.5 million cubic metre hangar fell into disuse. That is until some Malaysian investors bought it for a project that at first seemed even more crackpot: creating a tropical paradise where one would least expect it. Yet since then, after some initial difficulties, “Tropical Islands” has grown into a project bursting with superlatives: the world’s largest indoor beach and tropical indoor pool – able to accommodate up to 8,000 visitors a day, with the highest waterglide and biggest “tropical sauna-landscape” in Europe; and in between the resort’s “South Sea” and “Bali” lagoons is the world’s biggest indoor “rainforest” featuring over 50,000 plants, and ten flamingos.

-

The 5.5 million cubic metre former airship hangar in Germany was converted into a tropical paradise capable of accommodating up to 8,000 visitors per day.

-

Under its steel and glass firmament, Tropical Islands further boasts a myriad of shops, restaurants, bars, hotels, tents, and lodges, a whirlpool, a waterfall and even a hot air balloon. Recently a preliminary expansion plan was unveiled in which four villages would be built next to the hall, each devoted to one specific theme, from the Middle Ages to the fifties, which will turn the whole area into Germany’s largest amusement park. This is certain to boost the annual visitor figures already claimed to be more than a million: all holidaymakers enjoying an unchanging experience, where everything, from temperature to humidity remains the same 24/7, 365 days a year, safely removed from what some might still consider to be the essence of travelling – the risk of the unknown. I (Max Borka)

The “Aerium” hanger, originally built to accommodate giant airships for a failed transport scheme, is the largest free-standing hall in the world.

-

Dam it All

Building dams has been the basic, brute force way to control natural flows of water since at least 3,000 BCE. Many now think that humanitarian and environmental hazards caused by the construction of dams tend to outweigh the benefits. No such doubts attached themselves to the celebrated Hoover Dam project, on the border of Nevada and Arizona. This Great Depression era initiative to create jobs, produce hydroelectric power and provide water for irrigation nevertheless caused 100 worker casualties and, once completed in 1936, seriously messed up the ecosystem of the Colorado River Delta. These figures are chicken feed, though, compared to the fallout of the Three Gorges Dam spanning the Chinese Yangtze River, which, by its completion in 2010, had displaced approximately 1.3 million people, wrecked the surrounding environment with floods and landslides, and destroyed archaeological heritage sites. Three Gorges created the biggest power station in the world, but one has to ask whether the classic trade-off scenario still stacks up – or should we perhaps just damn dams? I (ew)

Photo courtesy U.S. Department of the Interior - Bureau of Reclamation.

-

Pink

Pipe

Dream![]()

All photos: Philipp Lohöfener / Wüstenrot Stiftung

-

With its remarkable form and odd colours, the “Pink Pipe” (1967-1974) is one of Berlin’s strangest buildings. It is commonly attributed to architect Ludwig Leo (1924-2012), but in fact Leo’s role in the project was limited. The project for a new Umlauftank (cavitation tunnel) for the Research Institute for Hydraulic Engineering and Shipbuilding was conceived and developed by the shipbuilding engineer Christian Boës, as a testing place for waterborne objects (read: boats). The layout of the facility, with its vertically oriented pipe and a testing hall riding on top, was determined by the physical requirements of the scientific facility. The object to be tested – for example, a model of a ship’s hull – is held in position at the top of the tank; the water, driven by a propeller at the bottom of the tank, is then circulated past the object.

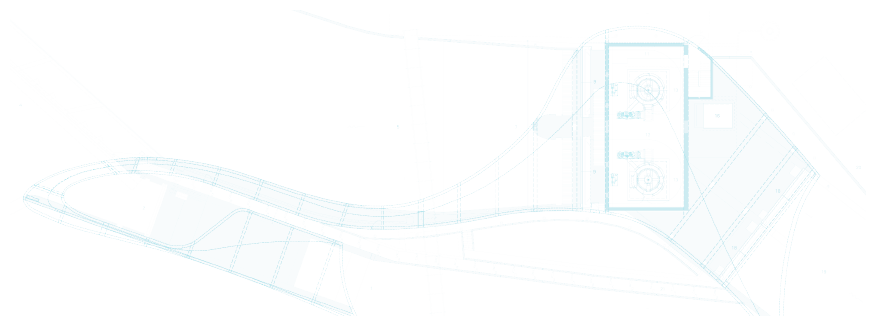

Drawing of the Umlauftank 2 by Ludwig Leo © Technical University Berlin

-

![]()

-

Leo was invited to provide artistic direction for the project. The ensuing collaboration between Boës and Leo resulted in a unique engineering/architecture hybrid. Leo succeeded in integrating his wide-ranging architectural sensibility seamlessly with Boës’ engineering concept. Leo gave the Umlauftank a sculptural and monumental presence by raising it on a concrete plinth and designing a mysterious, subtly anthropomorphic box, thus bringing the Umlauftank into dialogue with its urban context. No clear explanation has ever been given for the colours blue and pink, though oblique references to contemporary Pop Art and Archigram seem the most likely.

Looking from the bottom of the dried-out basin into the Pink Pipe: a spot where once a stream of water would have flushed you away.

-

Ludwig Leo was perhaps the most unusual architect working in West Berlin in the post-war period. He realised only a small number of very impressive buildings including the famous DLRG-Zentrale: a 11-storey tall boat house with a 44-degree slanting façade that integrates a lift for boats. Leo designed in a conceptual fashion and synthesised a wide variety of influences – aiming to offer a functionally optimised and architecturally appropriate solution for each specific task.

Apart from designing the Umlauftank, Christian Boës has completed quite a lot of engineering projects connected with water.

Jack Burnett-Stuart is a founding member of Berlin-based BARarchitekten, whose work concentrates on housing and mixed-use projects. The office has researched Ludwig Leo for over twenty years, and in 2013 joined Gregor Harbusch for the exhibition Ludwig Leo. Ausschnitt, the first exhibition about the architect’s work, for the Wüstenrot Stiftung.

Gregor Harbusch is an art historian with a strong focus on modern architecture and urbanism, currently finishing his PhD about Ludwig Leo at the ETH Zurich.

ludwigleoausschnitt.tumblr.com

bararchitekten.de

toennesmann.arch.ethz.ch

As its colours faded over the years, the Umlauftank has assumed a more melancholic character, reminiscent of the anonymous German industrial structures photographed by the Bechers. Its current restoration, supported by the Wüstenrot Stiftung as part of their programme for preserving the heritage of modern architecture, will see the exterior brought back to its original shocking colours and the device will be used again by four institutes at Berlin’s Technical University for diverse flow experiments. The restoration is planned to start in 2015 and to be completed the following year. I (Jack Burnett-Stuart & Gregor Harbusch)

About Ludwig Leo & Christian Boës

-

Dry Facts

Deserts cover a quarter of the earth, nourished by over grazing, poor land management and changing climate. The world population is 7 billion and rising, so available space is getting a little tight. Grassland ecosystem pioneer Allan Savory is on a mission to tackle desertification by rethinking land and livestock management in a holistic approach that takes into account nature’s complexity and our own as well.

![]()

»The most massive perfect storm is bearing down upon us«

Allan Savory, TED2013

Photos: Sagel & Krzykowski, video: TED.com

TTwW

Part 2/3

-

The Great Gyre

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, or the Pacific Trash Vortex, is a vast mass of marine litter trapped in the vortex of currents of the North Pacific Gyre, creating a concentrated “plastic soup” of fine particles, which is increasing at an alarming rate and killing millions of organisms annually.

If, however, you view this unsavoury mass as a resource, it makes sense to harvest it. UK designers Studio Swine and Kieren Jones proposed a “Sea Chair” made from ocean plastic harvested by a trawler a couple of years ago and now household eco-detergent company Ecover have taken up the idea to produce ocean-harvested plastic packaging for their biodegradable detergents.

»You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.«

R. Buckminster Fuller -

Pass the Salt

The city of Adelaide in Australia, located in the driest state on the driest continent on earth, has recently invested 1.8 billion AUD in a new desalination plant with the capacity to produce up to 300 million litres of safe drinking water per day from seawater – approximately half the city’s water needs. But what will happen to all the salt?

-

Oh Well

![]()

Photo: Edward Burtynsky, “Stepwell #4”, Sagar Kund Baori, Bundi, Rajasthan, India, 2010. © Edward Burtynsky, courtesy Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Galerie Röpke, Köln / Galerie Springer, Berlin.

-

Given the length of the dry periods between the annual monsoons in parts of India, maintaining a year-round supply of water has often required digging deep into the earth to tap the underlying groundwater. This has led to the development of a unique architectural form called the “stepwell”, which has been around since about 200 CE. Scaled to accommodate the massive swelling of the water table after the annual inundation, the eponymous stepped sides also enable communal access to the water.

To keep the exposed water as cool as possible, many smaller wells are partially covered to provide shading, whilst the larger ones are often deep enough to ensure water at the bottom remains cool. These chilled depths, contrasting with the hot sun above ground, set up convection currents within the well architecture, generating a similar cooling effect to that utilised by wind towers across the Middle East.

In the late nineteenth century, the British, worried about water hygiene, began to install pumped and piped water systems and the stepwells became redundant. Except for the most spectacular examples, which are maintained for tourists, the majority have been condemned to slow dereliction. I (rgw)

![]()

Photo: Edward Burtynsky “Stepwell #2″, Panna Meena, Amber, Rajasthan, India, 2010. © Edward Burtynsky, courtesy Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Galerie Röpke, Köln / Galerie Springer, Berlin.

-

Holding Back

the Waves

Climate Engineer Matthias Schuler on big projects and small footprintsInterview by Sophie Lovell

-

Matthias Schuler is founder of one of the world’s leading climate engineering firms, Transsolar, and teaches at Harvard Graduate School of Design. He has worked with Frank Gehry, OMA, Herzog de Meuron, Stephen Holl, Norman Foster and many others developing sustainable design strategies for everything from cabins to entire cities. He talked to uncube about thermodynamic entities, compost toilets and the measures we need to take if we are going survive the next flood.

You call yourself a “climate engineer”. What does that mean exactly?

As engineers and physicists, we understand buildings and cities as thermodynamic systems. We want to understand how they perform – not mechanically, but in their reaction to outside loads, such as wind and sun exposure. Energy, air quality and resources such as water are our focus and we seek to optimise performance by adapting forms and openings through “passive measures” – the building itself should do as much as possible. It’s important to be part of the design team from the start, so architects can integrate these measures, tailored to each individual building and its site: what we call local thermodynamic identity.

Talking of specific projects, you completed a tiny and self-sufficient building prototype recently with Renzo Piano for Vitra, called “Diogene”.

The main intention of that building was to show people you can live on a small footprint, not just spatially but energy and material-wise as well. This project was Renzo’s life dream; he first sketched it as a student and has worked on it throughout his career. Now finally he found Vitra to support it and even develop a product out of it.

It’s not intended to be a permanent home, more a weekend place or maybe an extension to an existing building.

-

![]()

The idea is you could place it wherever you want, unconnected to any form of civilisation, to any grid. No electricity, no water, no sewage, nothing. It will have limited capacity for energy-generation, water collection and storage, so at some point you may have to decide between a hot shower or warm food.

Therefore it was obvious it should do without a water toilet. This provoked one of the longest discussions with Renzo. He’s a sailor, and said: “you really have to love someone on a boat to share a chemical toilet”. That was his experience of the non-water flush toilet. But I told him we could use a compost toilet. We even installed one in the office which the whole company used for two months – with no smell problem.

The important thing with compost toilets is to separate the urine and faeces. When mixed, a digestion process starts, which creates the smell. If you separate them, it just dries off. Urine is a great fertiliser so you can use it for your tomatoes around your Diogene. The solid matter is collected in a self-composting bag which, when full, can be taken out, buried, and takes about a year to turn into soil.

![]()

Images courtesy Vitra

-

It’s very Walden, this idea of the Diogenes hut, isn’t it? Surely there are too many people in the world for us all to be able to go out and live like Thoreau in the woods.

Vitra is now going to make a hotel using about 25 Diogenes on their campus, but clearly they’ll have water-flushing toilets. And if you buy one for your garden you can connect it to the water supply if you want. For us it was about whether the house really can be autonomous for electricity and water. Toilets accounts for 80 per cent of our domestic water consumption: all over the world we’re flushing valuable drinking water down the drain. We need to distinguish between drinking water – of which we need perhaps five litres per day for drinking and cooking – from grey water used more as a hygienic element. That was the main lesson we learned from this project.

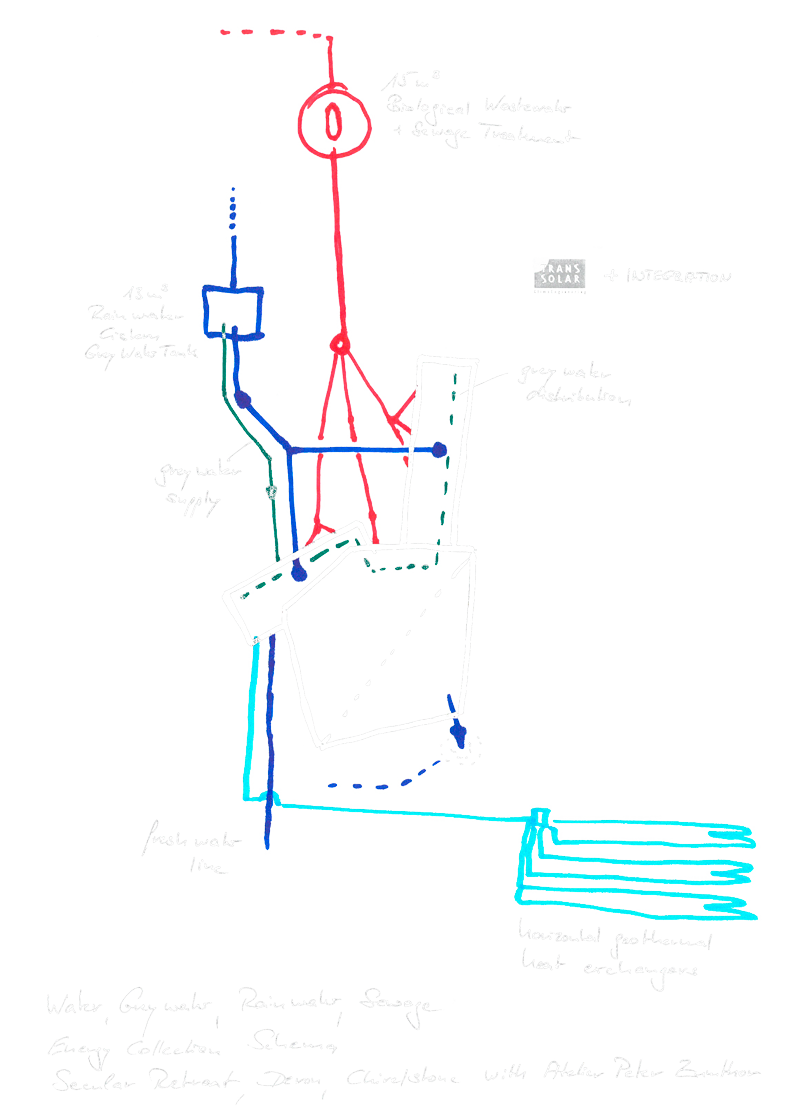

Tell me about the “Retreat” house you’re working on with Peter Zumthor in South Devon in the UK.

The project is part of “Living Architecture”, an enterprise which refurbishes old protected buildings and builds new, high-value, architecture for rent as holiday homes. I think it’s a great idea. Very few of us will ever live in a Peter Zumthor house, but you will be able to rent this for around 2,500 GBP per week and stay there with ten friends. The site is beautiful: on a hill overlooking the ocean. It has electricity but the water’s from a well, and there is no sewage.

So compost toilets again?

No, I couldn’t convince Peter. There will be water flush toilets. We talked about a biological reed-bed filter system but this is hard because it’s on a hill. So we have a three- or four-stage enclosed treatment system. The water that comes out is quite clean, so we can run it on site. This is the most state-of-the-art water treatment that’s possible on an independent site.

-

That’s interesting because one doesn’t usually associate Zumthor buildings – or retreats – with high tech or “state-of-the-art”.

You’re right: I can imagine such a building by Zumthor with just water and no electricity, nothing else. But if you rent something for that amount, even if it’s a Peter Zumthor house, people still expect WiFi.

Turning to the other end of the scale, you did the climate concept for Norman Foster’s Masdar City masterplan in Abu Dhabi due to be six square kilometres in size.

The energy and climate concept for Masdar is one thing, but the water concept is also interesting. When we were approached to develop this carbon-neutral city with Foster, we had to include water treatment because there’s no fresh water in Abu Dhabi. The only water available is from the shallow Arab Gulf, which is 30 per cent more saline than normal ocean. For the past 20 years local states like Quatar and the UAE have all been surviving on desalinated water.

![]()

Image courtesy Matthias Schuler

-

With this process you take the sweet water out and pump the highly concentrated saline residue back into the Gulf: a disaster environmentally. The typical corals and mangroves of the Gulf have been lost as the salinity of the Arab Gulf has increased by two percent.

So one of the first lessons we learned was: thinking we can solve the water problems in the Middle East with solar-driven desalination is wrong. Energy-wise it might be okay, but overall this highly concentrated brine residue is a real load. Our Masdar energy concept showed that we would produce 120,000 tonnes of salt a year:, but what to do with it?

![]()

![]()

» Thinking we can solve the water problems in the Middle East with solar-driven desalination is wrong.«

Images courtesy Foster + Partner

-

What stage is Masdar’s construction at now?

Around 25 per cent of the university is built and in operation – some 50,000 square metres – and the huge Siemens HQ for the Middle East is under construction, as well as the Abu Dhabi Energy Foundation. Foster is working on detailing the first 25 per cent of the city, transforming the masterplan into actual buildings. In my opinion, though we may never see all Masdar built as planned, the lessons learned will impact majorly on future developments. This is what I see as the big potential of Masdar City: that it creates an example for everybody who is starting in the same direction.

We’ve had brainstorm sessions with the German chemical company BASF and they came up with ideas like encapsulating salt crystals in plastics to add to road material. But we’re still working on it.

Another issue is that daily water consumption in Abu Dhabi today is 500 litres per person. By contrast, the French are down to around 130 litres and the Germans close to 150. So in a region where water is a rare resource, they’re consuming triple the amount used in European countries, which includes water for all the golf courses and the 400 million trees planted along Abu Dhabi’s highways. Emiratis wash their cars three times a week because of the dust – yet don’t pay a single dollar for water or electricity. Only expats are required to pay.

» Though we may never see all Masdar built as planned, the lessons learned will impact majorly on future developments.«

-

Transsolar is currently working on the Al Fayah Park project with Heatherwick Studio in Abu Dhabi. The target, says Schuler, is to create an “urban cold island” by using shading, ventilating the streets at night with wind towers and keeping the hot, humid winds out during the day, thus reducing ambient temperatures from 40 to a more bearable 35 degrees Celcius. (Images courtesy Heatherwick Studio.)

-

Matthias Schuler is Adjunct Professor of Environmental Technology. He has held the position of Lecturer in Architecture at the Graduate School of Design (GSD), Harvard University since 2001, teaching courses in sustainability and climate engineering.

He founded Transsolar Energietechnik in 1992 based in Stuttgart, Germany which has become a leading provider of consulting services on developing sustainable design strategies for buildings.

Schuler has worked with a large number of well-known architects in the field on high-profile projects including: Herzog de Meuron (Parrish Art Museum, Topeak Towers); Stephen Holl (Linked Hybrid, Herning Art Museum); Jean Nouvel (Musee de la Mer, Philharmonie Paris, Louvre Abu Dhabi); Gehry Design Architects (Novartis, Museum of Tolerance, World Trade Center Performing Arts Center); Murphy/Jahn (Suvarnabhumi International Airport in Bangkok, Posttower) and OMA (Center for Performing Arts, Museum Plaza). He has also produced energy and comfort solutions at the urban master plan level, like the carbon-neutral Masdar development in Abu Dhabi in conjunction with Foster + Partners.

Masdar, as well as your new Al Fayah Park project with Heatherwick Studios, are environments created from scratch in extreme conditions. What about interventions within existing buildings and cities? Should we knock down old inefficient structures and start again?

No, around 75 per cent of the embedded energy of a building is in its structure. So whilst you can replace its façade or technical systems, holistically, energy-wise it would be a crime to tear it down and build anew. A rough rule of thumb is that even for very low-energy buildings, it’ll take around 15-20 years to make up for the energy wasted in destroying the old one.

This leads us to the recent news of the Thwaite ice sheet’s collapse in Antarctica with sea levels now predicted to rise by up to ten feet over the next two centuries. If these predictions are true, massive changes are coming.

We’ve known this since at least 1972. At the time of the Club of Rome, they were already showing the limits of growth. The only thing we can do is change our social systems.

Take the ETH Zurich 2000-Watt Society proposal for getting annual carbon emissions per person down to one tonne. This is exactly the kind of proposal to show the world – that it’s possible to do this yet keep a high-quality lifestyle. We must rethink our idea of luxury, asking ourselves: do we really need three TVs, walk-in refrigerators or whatever.

Realistically, we can’t now save the world from some changes. There are already areas with annual temperature rises close to 2.5 degrees Celsius. Instead, we need our systems to be adaptive. This doesn’t mean everybody going and living in retreats without electricity or running water, but we do each need to live on a smaller footprint. p -

Leandro Erlich was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, where he lives today. Erlich creates uncanny spaces with fluid and unstable boundaries, drawing inspiration from Jorge Luis Borges, Alfred Hitchcock, Roman Polanski, Luis Buñel and David Lynch. In 2001 he represented his country in the 49th Venice Biennale, and has also participated in the Biennials of Istanbul (2001), Shanghai (2002), São Paulo (2004), the Whitney Biennial (2000) and the 1st Busan Biennale (2002). Ehrlich has presented at La Nuit Blanche, the Palais de Tokyo, the Museo Reina Sofia, and MoMA PS1, among many other spaces.

Lonely as a Cloud

Water, in all its forms, is a central element and metaphor in the work of Buenos Aires-based artist Leandro Erlich, who calls himself an “architect of the uncertain”. The title of his project, Single Cloud Collection, jokingly points to the uncertain qualities of H2O and the collective nature of clouds; his clouds may be isolated in individual boxes, but each is created from a compilation of layered glass sheets with acrylics applied to give the illusion of depth. Just as a real cloud is a conglomeration of billions of water droplets, these frozen cloud images are but illusions of singularity. I (ew)

Leandro Erlich, “Single Cloud Collection”, 2012. Courtesy Galería Ruth Benzacar, Buenos Aires, Argentina. (Photo: Ignacio Iasparra)

-

Stream

linesText by Anneke Bokern

-

The Dutch are famous for their never-ending struggle against the water that constantly threatens to inundate its “low countries” from all sides and it can only be kept under control with a great deal of technical effort. It’s less well known that, in a kind of reverse logic, water was also used as a defence mechanism for several centuries in the Netherlands. From the seventeenth century onwards, various water lines were created in the Netherlands: long stretches of uninhabited land that could be flooded for defence purposes.

This and previous page: In 2010, Rietveld Architecture Art Affordances sliced open one of the 700 little bunkers of the New Dutch Water Line. A wooden boardwalk leads through it onto a flooded basin that was once part of this water defence line. (Photos: RAAAF)

![]()

-

Fortresses, and later also bunkers, lying in the landscape like pearls on a string, served as extra protection for cities and higher ground. In case of an invasion, the inundation locks were opened until the land stood 40 cm under water – just enough to make it impenetrable for soldiers, wagons and horses, but too shallow to navigate by ship.

The water lines were maintained and constantly modernised until 1940, when German aerial attacks proved mud soup to be a rather out-dated defence tool.Fort Diemerdam is part of the “Stelling of Amsterdam”, a UNESCO world heritage site. Existing bunkers, guardian houses, slopes and strongholds have been restored, and Emma Architecten have inserted a new wooden pavilion where events, guided tours and catering is organized. (Photo: John Lewis Marshall)

-

Despite being disused, the lines are still recognisable in the landscape today, and in 1995 the New Dutch Water Line, which is 85 kilometres long and roughly encircles the Randstad agglomeration, was proposed for the UNESCO World Heritage list. The same line is designated as a national project envisaging “preservation through development” until the year 2020. Forts have been opened and waterworks restored, sometimes resulting in sizeable land art projects. Most of the old fortresses and also some of the bunkers – which, to the annoyance of many a farmer, are too solid to demolish – have been repurposed as sights and tourist destinations. I

The Fort Werk aan ’t Spoel was built in 1794 to protect one of the flood locks of the New Dutch Water Line. Integrating old bunkers and a new Fort house, RAAAF turned the huge amphitheatre-like fort into a playground for cultural and leisure activities. (Photo: Rob ’t Hart)

-

Death on the Nile

The facetted dome of this sham grotto, the Serapaeum, once resounded to the rushing of artificial torrents, gurgling fountains and cascades: a sensuous interior water world surrounding a podium where the Emperor Hadrian and his friends once reclined to dine. Called a triclinium nymphaeum (literally: “dining room as fountain”) it is part of the villa the emperor built at Tivoli, outside Rome between 118-134 CE – as a vast memory palace, with many of its buildings representing places in the Roman Empire he’d visited. This sumptuous pleasure dome, fronted by a canal, had very personal significance for the Emperor. It was associated with the River Nile, where his lover Antinous had drowned. And among the sculptures of a crocodile and pseudo-Egyptian statues excavated, one of Antinous was found, dressed as the figure of Osiris, God of the Upper Nile, who dies and is reborn. So hope, not just water, sprang eternal here too. I (rgw)

Giambattista Piranesi, “Remains of the Temple of the God Canopus in Hadrian's Villa at Tivoli” (from “Views of Rome”). (Image courtesy Giorgio Cini Foundation, Venice, the Cabinet of Drawings and Prints)

-

Underwater Love

Chris Bosse on water, nature and Frei Otto

Interview by Sophie Lovell

Photo courtesy LAVA

-

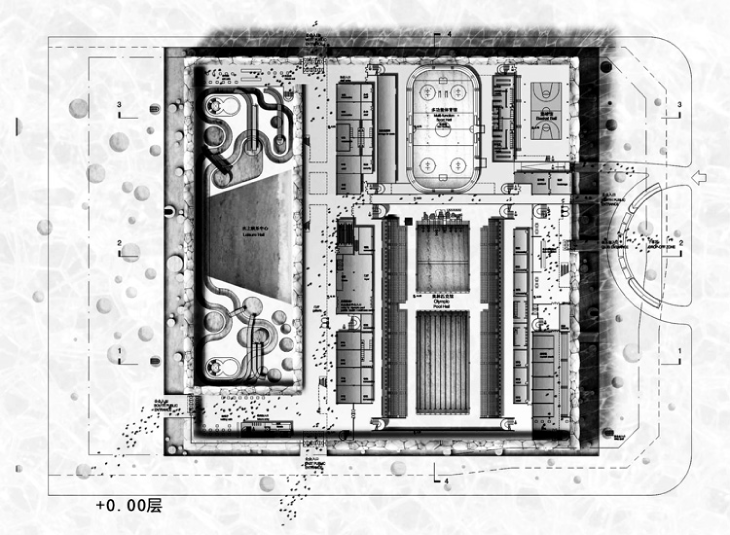

Chris Bosse is one of the co-founders of LAVA, the Laboratory for Visionary Architecture, an international architecture and design practice strongly inspired by biomimetics. Bosse was a key designer of the Watercube, the National Aquatics Centre for the 2008 Beijing Olympics. Thanks to his focus on the computational analysis of organic structures, this extraordinary building has a façade that is simultaneously space, structure and metaphor. LAVA was also involved in the transformation of the Watercube into its current incarnation as the Happy Magic Water Park, a playground for Beijing aquaphiles. Bosse spoke to uncube about the giant water baby that made his name.

-

![]()

LAVA is known for its rather outlandishly organic architecture, but your work is more than skin deep. How closely do you implement the analysis of natural forms and structures within your buildings?

I love architecture when it has multiple layers of structure, of meaning, of relevance. I don’t like façades that are pure applications to hide an otherwise utilitarian box. When we look at nature, we always try to understand what is going on and translate that into coherent systems. To reconcile this approach with commercial pressures in architecture is not always easy, but in every project we find these moments of magic.

Apart from the fact that the Watercube had a very clearly defined functional brief, how did you arrive at the very watery aspect of the skin and structure?

The Watercube was an attempt to unify wall, roof and floor – structure, skin and space – into one element. We investigated space-packing systems found in nature, turning to corals, foam and soap bubbles. Frei Otto at the Institute for Lightweight structures in Stuttgart taught us to use soap bubbles as a form-finding method for structure and space, and he was a great inspiration. His 1972 Munich Olympic stadium roof is still unsurpassed.

-

![]()

Was metaphor intended, or was the design simply a search for lightness and visual impact?

When we started the competition we googled keywords like water, bubbles foam and corals and found intriguing imagery. We mocked up moodboards, which became the guiding visuals throughout the competition. An earlier version of a gigantic wave turned out to be too literal and was rejected in favour of the more subtle adaptation of “cubed” water.

The repurposing of former – incredibly costly – Olympic buildings has become a big theme in recent years. For example, the later downsizing of Zaha Hadid’s Aquatic Centre for the 2012 London Olympics into a local swimming pool, was incorporated into the original construction plan.

![]()

Photos courtesy WhiteWater West (interior) & LAVA (exterior)

-

![]()

![]()

Floorplan image courtesy LAVA. Photo: Ben McMillan.

-

Chris Bosse, Tobias Wallisser and Alexander Rieck founded LAVA in 2007. It was established as a network of creative minds with a research and design focus and has offices in Sydney, Shanghai, Stuttgart and Abu Dhabi. LAVA explores frontiers that merge future technologies with the patterns of organisation found in nature and believes this will result in a smarter, friendlier, more socially and environmentally responsible future. LAVA designs everything from pop-up installations to master-plans and urban centres; from homes made out of PET bottles to “reskinning” ageing 1960s icons; and from furniture to hotels, houses and airports of the future.

l-a-v-a.net

![]()

Your office was also involved in the transformation of the Watercube into the leisure facility it is today. Can you describe the process, and are you happy with the changes?

We designed the Watercube from the beginning in two modes: “Olympic mode” and the so-called “legacy mode”, the difference being 12,000 fewer seats. In post-Olympic mode the Watercube turned into restaurants, shops and a gigantic leisure pool full of colourful rides and water games. We weren’t involved in the actual realisation as the building had by then been taken over by the client, but I am quite relaxed about it and happy with how full of life it is now. There are some interesting moments, for example, when a Chinese restaurant meets contemporary architecture, or when Watercube merchandise shops dominate the galleria.

The structure was highly innovative – how is it standing the test of time?

Beijing, of all places, has the potential and the population to draw millions of visitors annually. Reportedly the Watercube is the second biggest tourist attraction after the Great Wall (which I find hard to believe, but that’s what they say). The test of time is always in the maintenance, which they are doing ok. But, most importantly, I think the design is strong and timeless – and now, ten years after the competition, it looks as fresh as ever. I

-

Barrier Reef

One of the best lines of defence against tidal wave damage has proven to be coral reefs, which weaken a tsunami’s impact before it hits shore. The devastating effects of the Sumatra tsunami from 2004 could have been greatly reduced if the coral reefs off the coast of Sri Lanka hadn’t been largely removed by humans.

There are a number of coral regeneration projects in operation worldwide. A method developed by architect Wolf Hilbertz involves submerging steel structures charged with an electric current which draws calcium carbonate onto the surface of the structure, creating a magnet for new coral to feed on.TTwW

Part 3/3

Photos: Sagel & Krzykowski

-

Fishy Business

Back in 1973 when Jacques Cousteau advocated fish farming as a way out of the destruction of the world's fish stocks, it seemed like a good idea. Forty years later, aquaculture is the world’s fastest growing industry and nearly half of all seafood is farmed - but the ecological damage it causes is quite shocking. Aquaculture needs to get sustainable and a system of “integrated multi-trophic aquaculture” seems to be the way forward: the co-culture of a number of species at different trophic levels in niche systems which help regulate much of the harm caused by current monoculture practices. Projects underway include the AquaFish Collaborative Research Support Program in Thailand and Indonesia, which combines production of tilapia, mud crabs, seaweeds, milkfish, and mussels.

»It is time to farm the ocean as we farm the land.«

Jacques Cousteau 1973

-

Not Waving but Drowning

In Northwest Alaska permafrost is melting, sea levels are rising, and entire villages are falling into the sea. The whaling community of Kivalina, home to some 400 people, is facing imminent relocation and the need for viable futures is urgent. For a host of reasons, previous relocation efforts in Kivalina are stalled, leaving the community looking for alternatives. ReLocate, a group of social artists from around the world are using social media to initiate a new, kind of community-led and culturally specific relocation. p

![]()

Video courtesy “Modelling Kivalina” working group.

-

Ooho, the edible water bottle

Skipping Rocks Lab, a team of design students from London Imperial College and Royal College of Art, recently revealed an invention that could help eliminate one of the world’s biggest environmental threats: plastic pollution. Called “Ooho”, the biodegradable blob bottle is made from a double gelatinous membrane of calcium chloride and brown algae. It can be safely thrown away – or even eaten. What’s more, anyone can make an Ooho at home without any fancy equipment. It was inspired by the structure of an egg yolk, and borrows its design from the “spherification” technique first used by the culinary industry to make fake caviar in the 1950s, and later for bubble tea. The main innovation of the Ooho is the size of the bubble. Still in its testing phase, Ooho still has some kinks – it’s not resealable, for instance – but the team is confident that someday soon it will be ready for mass production. I (Max Borka)

Photo courtesy Skipping Rocks Lab

-

![]()

Kraftwerk

ArtworkPhoto: Brigida González, brigidagonzalez.de

-

becker architekten, founded by Michael Becker in 1998, is a four-man team located in the alpine region of Allgäu in southern Germany. With a conceptual approach towards architecture that examines location, identity, topography and history, the firm aims to realise projects that focus on the creation of a harmonious atmosphere.

becker-architekten.net

The Bavarian town of Kempten, which dates back to 50 BCE and has the oldest written reference of any German city, now has a rather surprising architectural centrepiece – which also happens to be a highly efficient hydroelectric power station.

Wasserkraftwerk Kempten harnesses the power of the river Iller and supplies some 3,000 households with 10.5 million kilowatts of “clean” electricity per year. The raw concrete power station’s irregular form, inspired by water-worn rocks from the region, is designed by local architects becker architekten. It provides a visual as well as metaphorical contrast to its predecessor, a neighbouring conventional power station from the 1950s, communicating through its form and function the advancements in sustainable technological design. I (ltv)

Image courtesy becker architekten

-

![]()

This innovative book aims to help teach water hygiene to some of the nearly 1 billion people around the world who don’t have access to clean water for basic needs like drinking, cooking and washing. And, uniquely, it also provides cheap water filters, formed from its tear-out pages, which are designed to kill the bacteria that cause 3.4 million people to die each year from water-borne illnesses. It was created by the humanitarian charity WATERisLIFE and ad agency DDB, teaming up with American researchers from Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Virginia, and is based on technology invented by chemist Dr Theresa Dankovich and further developed by New York-based typographer Brian Gartside.

![]()

-

The Drinkable Book was designed and produced by Brian Gartside, WATERisLIFE, Carnegie Mellon University and the University Of Virginia. The mission of WATERisLIFE is to provide clean water through sanitation and hygiene programs.

Find out how you can provide someone in need with a Drinkable Book here.

Max Borka was born in Belgium in 1954, and currently works as a journalist, critic, lecturer and consultant in Berlin. He has written numerous books and curated exhibitions and events in the fields of art, architecture, fashion and design, including. As the former Director of the Interieur Foundation in Kortrijk, Belgium, he was the founder and first Editor-in-Chief of DAMn° magazine and recently launched Mapping the Design World, a worldwide platform on social design. He currently teaches Design Theory and History at the Fachhochschule Potsdam.

![]()

The soluble book is printed in food-grade ink on paper coated with silver nanoparticles. Every copy comes packaged in a 3D printed box, which converts into a filtration tray. After each page is torn out and slipped into a slot in the tray, it serves as a water filter, with the nanoparticles decreasing bacteria in contaminated water by more than 99.9 percent, making it potable. Each book is said to contain enough pages to filter up to 5,000 litres, providing a family’s drinking water for up to four years. An initial run of 100 copies was printed in English and Swahili to be sent to Kenya, but WATERisLIFE also plans to distribute it around the world after further testing, and hopes to raise funds for a commercial release in 2015. I (Max Borka)

-

![]()

-

![]()

Photo: Nuno Cera, “Futureland”.

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Less is a bore.«

Robert Venturi

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents