-

Magazine No. 30

Animal House

-

No. 30 - Animal House

-

page 02

Cover

Animal House

-

page 03

Editorial

Animal House

-

page 04 - 07

Jumbo Dome

The new Kaeng Krachan Elephant Park, Zurich

-

page 09

"I will name him George..."

Michelle Bours' pet portraits

-

page 10 - 18

The Logical Path

Interview with the extraordinary Temple Grandin by Sophie Lovell

-

page 20

The Empty Cage

Artist Wesley Meuris' melancholic zoo

-

page 21 - 24

Social Housing

Bird communes in the Kalahari photographed by Dillon Marsh

-

page 25 - 27

Crabby Chic

Artist Aki Inomata's real estate for hermit crabs

-

page 28

Tanks For All The Fish

Shopping mall-as-aquarium in Bangkok

-

page 29 - 38

Beastly Designs

Ned Dodington's barrier-free survey of zoo architecture and design

-

page 39

Fly Inn

B&B's for bugs

-

page 40 - 44

Homes Without Hands

Instinct or intelligent design? The nineteenth century debate on animal architecture

-

page 45 - 46

Kitty Kawaii

Cat Island in Japan

-

page 47

Pigeon Pylon

Oscar Niemeyer's dovecot

-

page 48 - 52

Down On The Farm

Good design for livestock

-

page 53

The Final Indignity

Animal furniture

-

page 54

Next

Poland

-

-

uncube's editors are Sophie Lovell (Art Director, Editor-in-Chief), Florian Heilmeyer, Rob Wilson and Elvia Wilk; editorial assistance: Fiona Shipwright; graphic design: Lena Giavanazzi.

uncube is based in Berlin and is published by BauNetz, Germany's most-read online portal covering architecture in a thoughtful way since 1996.

![]()

![]()

We eat them, we worship them, we share our lives, love, land and homes with them; animals occupy the architecture of our lives in so many ways. In this unashamedly zoophilic issue, we take a critical look at zoo architecture and the changing shape of human-made animal habitats, interview the extraordinary Temple Grandin about designing more humane structures for the millions of cattle sent to slaughter, and focus on functional – and just plain funky – examples of livestock living quarters down on the farm. Last but not least, we explore some extraordinary examples of animal-building that show nature to be still the greatest architect on the planet.

So cuddle up to our fluffiest issue yet, but watch out for the claws.

Cover image from Aki Inomata’s series “Why Not Hand Over a ‘Shelter’ to Hermit Crabs?”, 2010-2013. (Photo © Aki Inomata)

-

![]()

![]()

Jumbo Dome

The new Kaeng Krachan

Elephant Park, Zurich

All photos shot especially for uncube by David Willen.

-

Zurich Zoo’s Elephant Park is quite literally a tour de force on all levels: to start with, the sloping site just north of the original enclosure presented a challenge for its integration into the landscape, which the zoo required to be “as natural as possible”. Then there was the self-supporting roof which was structurally sound on paper but turned out to be a considerable challenge in terms of its construction and statics, while the long process of planning and realisation demanded exceptional commitment too from all concerned. Funded by both sponsors and benefactors, the Kaeng Krachan Elephant Park ended up costing 57 million CHF instead of the budgeted 32 million and opened two years later than planned – but the effort has been worth it.

The Elephant Park project, a collaboration between landscape architects Lorenz Eugster, architects Markus Schietsch Architekten and engineers Walt + Galmarini, is at 11,000 square metres, some six times larger than the old enclosure. More space means not just more comfort for the noble pachyderms, but also allows for better social relationships within the herd. The compound can accommodate up to ten animals that can choose freely whether they want to be inside or outside. In addition, the elephants needed to share the enclosure (as they would in the wild) with other hoofed animals and wild fowl, and thus have had to learn to accustom themselves to the presence of these other species.

![]()

-

![]()

-

Roderick Hönig was born 1971 in Switzerland. He studied architecture at the ETH Zurich and the E.T.S.A. Barcelona and received a CAS in Arts Management from the University of Berne. He has worked for the Neue Zürcher Zeitung as well as for the Museum of Modern Art in New York. He has also edited several books including: Swiss Sound Box, the catalogue for Peter Zumthor’s Pavilion at Expo 2000 in Hannover, ImagiNation, the official catalogue of the Swiss National Exhibition Expo 2002, and the Architectural Guide Zurich. In 2005 he was awarded the Swiss Arts Award in the category Arts and Architecture education. Today Hönig is manager of Edition Hochparterre in Zurich.

The care of the elephants is also new and more species-appropriate: the keepers no longer have any direct contact with the animals – and are thus in less danger of injury. In tandem with the building of the new elephant park, Zurich Zoo is also supporting a project in Thailand, the Asian elephants’ native homeland, helping protect them in the wild by attempting to resolve the “human-elephant conflict” with farmers there.

The two main elements of the park are a 5,000-square-metre outdoor enclosure and a spectacular covered hall. Outside, the landscape is designed to be like a clearing oriented around a dry riverbed. Here there is a cow and calf section, a bull pen, three bathing pools, a mud wallow and waterfall area. The visitors’ path meanders artfully through the enclosure and at selected spots the clever scenography allows carefully composed views through a new “forest” onto individual sections. The viewing experience climaxes in the hall itself, which offers a spatially spectacular, naturally lit environment.

![]()

The self-supporting structure of the timber shell spans up to 88 metres and covers almost 7,000 square metres. This double curved shell carries its 1,200-tonne weight elegantly and efficiently, with the loads borne by enormous concrete slabs in the basement. On top rests the pièce de résistance, a wavelike, 270-metre-long, 200-tonne, pre-stressed concrete ring beam.

The 271 polygonal skylights that cut into the roof, all different, do not make the redistribution of the roof load any simpler. To save weight, the openings are filled with UV-permeable air cushions up to 35 square metres in area. These need to be constantly inflated which requires two compressors in the technical catacombs buried beneath the 80-centimetre-thick sand floor. In fact the whole building is a gigantic high-end, high-tech utilities machine disguised as a hut. Even in its accommodating cellar there is an in-house purification plant feeding the lucky elephants’ very own indoor, glass-sided swimming pool. I (Roderick Hönig)

-

![]()

SEQUENCE – integrated intelligence

The SEQUENCE LED luminaire for offices has been completely redesigned to meet users’ basic needs for personalised lighting, using the current options provided by LED technology to full effect in all aspects.

-

“I will name him George

and I will hug him, and pet him, and squeeze him”We design our homes, our tools, our cities and our food – and we also design the animals we like to share our houses with. Elegant, daft, smart, huge, tiny, childlike, passive or aggressive, there is a pet bred for every requirement – even a breed of cat called a Ragdoll designed to go limp and floppy when you pick them up.

For her graduation project in 2014, the young Dutch designer Michelle Bours took a critical look at the odd propensity human beings have for keeping pets. “While we love our dogs and believe there is a mutual understanding between us and our four-legged friends, we also control their actions, demanding obedience, and even manipulate their appearance through breeding programmes”, she says. Bours created a photo series to reflect this rather dubious relationship we share with our pets called Overwhelming Love, stating: “With these photographs I want to confront people with the awkward position in which we place our pets.” Cute and disturbing in one. I (sl)

Benjamin, from the “Overwhelming Love” series by Michelle Bours. (Image courtesy Michelle Bours)

-

The

Logical

PathInterview with Temple Grandin

By Sophie Lovell

-

![]()

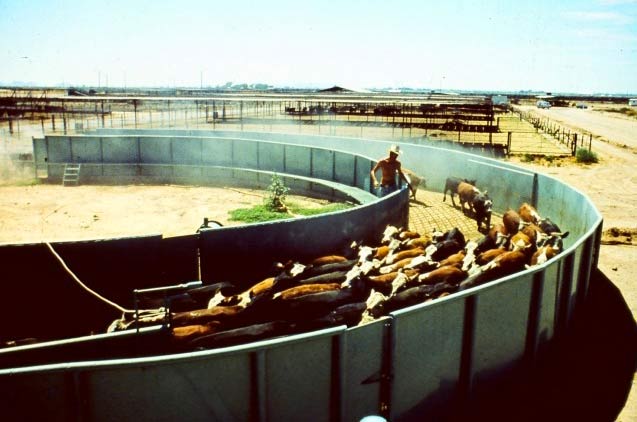

Whatever your feelings about eating meat, with hundreds of thousands of beef cattle slaughtered every day for human consumption, we have the responsibility to ensure the animals we consume go to their deaths in as humane, gentle and painless a way as possible. The animal behaviourist Temple Grandin, well known also as an eloquent spokesperson for autism from her personal experience as an autistic person, has perhaps done more than any other individual to ensure this is the case. Her way of thinking is one that not only cattle handlers could learn from…

You are highly recognised for your work in improving cattle welfare through your design of livestock handling systems. How did you first became interested in livestock welfare?

Students only get interested in things they are exposed to – and I was exposed to cattle in high school. My boarding school had a twelve-cow dairy, and when I was 15 I went to my aunt’s ranch, where I got exposed to beef cattle.

When did you become aware that there was a problem there that needed addressing?

At our high school they treated their cattle really well. There were no problems, and they were beautiful cows: Milking Shorthorns. It wasn’t until I got out to the West and to Arizona that I started seeing really bad handling of cattle at large feed lots. They were just so rough with the animals. And I noticed that sometimes the animals would refuse to go through the race [a narrow corridor built for handling cattle] because they had stopped at a shadow, or because a rope was hanging across it, or a coat was on the fence. So I actually got down in the raceway to see what the cattle were seeing. Nobody had done that before. This was the early 1970s − it was considered really far out.

Previous page: Temple Grandin. (Photo: Rosalie Winward, courtesy Colorado State University)

-

How did you move from these observations to designing your first stock and slaughter pen designs?

The stock pens came first because I got interested in the feed yards, but I started visiting a local Swift [meat processing] plant in Arizona and one of the questions I asked was: are cattle afraid of getting slaughtered? So I’d go to the Swift plant and then the feed yards, and watch the cattle being handled. But they behaved the same way in both places. You can see videos online showing animals going into a slaughterhouse and they’re all upset and agitated. Well, one of the reasons they’re upset is because they’re alone. Animals do not like being alone; they get upset.

How have you changed the format of the pens to make the experience better for the cattle?

Cattle’s natural behaviour is to go back to where they came from. When you lay out a crowding pen, you should lay it out in a full half-circle, so the cattle come around the pen back where they come from. That’s an important principle. Then it’s really important to get all the distractions out of the system. Animals are really sensitive to what they see − it’s amazing the little things that they notice. Just the other day I went into a plant with one of my systems which was not working well. I looked at how the cattle were moved, and there was a place where they could see people and motion up ahead. So I took a piece of plastic and hung it up to block their vision and it worked so much better. All it took was a piece of plastic to make the difference.

There are also plants where I’ve just added lighting. Animals do not like to go into the dark. So you add a light in the right place and then they’ll follow, or you move a light to remove a reflection on the floor.

All layout drawings by Temple Grandin for cattle holding pens. (Images: © Temple Grandin)

-

In two plants the reason the cattle weren’t going up the race was paper towels hanging up on the side. I took them away and it worked. These are things most people don’t notice. I also show people how to move cattle. A real common mistake is to stand at its head and poke it on the butt − so you are telling it to go forward and back at the same time. That does not work.

So changing people’s behaviour is also key?

One of the things I found was that selling the equipment I designed was easy. Getting people to actually be gentle with the cattle and operate things correctly were the difficult parts. People always think they can buy the magic facility and it will solve the problems, rather than changing the management. But people are half of the equation. When I started out in the ’70s, as a girl in a man’s world, I was looked at like I was crazy. People handled cattle so badly in the ’70s. Just getting them to stop poking them all the time with electric goads was hard enough. Today many people are interested in low-stress handling but when I started I was totally a pioneer.

Now things have gotten better. One major factor was big companies, like McDonalds, auditing. In 1999 I worked on implementing the McDonalds audit and saw more change in that year than I’d seen in my whole career. Now people have to maintain equipment, repair equipment and operate it correctly.

Because they had the pressure of their main buyer checking on them?

Because McDonalds kicked them off their supplier list if they did not. I hate to say it, but it took that to force people to actually operate correctly.

-

![]()

![]()

»Cattle’s natural behaviour is to go back to where they came from«

Photos courtesy Temple Grandin.

-

On what scale have your designs been implemented? How many plants and cattle are we talking about?

Well, my centre track restrainer and conveyor systems are in most of the big, big plants, which handle about 50 percent of all the cattle in North America, including Canada. People say I have designed half the cattle handling systems in the USA. That’s not true, but half the cattle going to meat plants go through my centre track restrainer system. The other main systems I’ve designed are feed lot handling and ranch systems, but the percentage of cattle that go through these is much lower.

How many people do you have working for you?

I just have one employee doing electronic CAD drafting for me now.

So people still come to you asking for a design?

Yes, and then we design it specifically for their place. Although my career is changing and I’m now doing a lot of talks at colleges and things like that, I’m still getting out in the field.

-

Also, some people read my stuff on the internet, then send me a drawing and ask if I approve of their design. I look at a lot of drawings that people send me and if they lay them out right I say “go ahead and build them”, but there are some bad layout mistakes you can make. If you are using curved facilities it’s really important that they’re laid out correctly – they have to be. It’s critical when you bring a group of cattle down to single file that they can see two body lengths up that raceway – to see that there is a place to go. People tend to bend it too sharply right where it joins the group pen. That’s what I call “dead-ending the race”. It won’t work if you make that mistake.

Which countries would you say have been most receptive to your designs?

Mostly countries that handle large amounts of cattle: Australia, South America, the USA… I have some much smaller systems in England using a round crowd pen with a half-circle turn and a straight chute.

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

»It’s really important to get all the distractions out of the system«

![]()

All photos courtesy Temple Grandin, except top/left: William A. Cotton/Colorado State University Photograph.

-

Dr. Temple Grandin, born in 1947 in the USA, is a designer of livestock handling facilities and a Professor of Animal Science at Colorado State University. With a PhD in animal behaviour, she is a best-selling author, an autism activist and a consultant to the livestock industry. She is well known for inventing the “hug box”, a device that calms those on the autism spectrum. She has been listed in the Time 100 as one of the hundred most influential people in the world in the “Heroes” category. Her life story has also been made into an HBO movie titled Temple Grandin, starring Claire Danes, which won seven Emmy awards and a Golden Globe.

grandin.com

templegrandin.com

grandinlivestockhandlingsystems.com

I’ve a bunch of those there and they love ’em. But a lot of my principles, like those about distraction, everybody likes, because they apply to everything – large and small.

You have had such a full career. Which achievement are you most proud of? What keeps you going and keeps you interested?

I’m proud of the design part, but also of teaching people to be more observant. I keep going and I do a lot of talks at colleges because I want to get students interested. There are a lot of kids out there who are a bit different, who might be labelled autistic or dyslexic or maybe with ADHD, and too many of them get a handicapped mentality. I want to see them get out there and get good careers. The head of Ikea was dyslexic, Einstein would be labelled autistic today, and Beethoven was pretty weird.

![]()

-

ThE Empty Cage

The Chinese Softshell Turtle, or Pelodiscus sinensis, is an olive-brown turtle with a splotchy, flexible shell, webbed feet, and a long snout. Its presence in the wild is threatened both by changing environmental conditions and by its tastiness; in many parts of Asia, Pelodiscus meat is a popular delicacy, and farms across China breed the turtles for food.

In his installation work Cage for Pelodiscus Sinensis (pictured here) from 2006, part of his ongoing Zoological Classification project, the Belgian artist Wesley Meuris displayed an empty habitat labelled as an enclosure for the Pelodiscus.

But whether this particular cage was meant as a sanctuary to preserve a diminishing species, for farming it as food, or for its zoo-like display was not determined and the viewer was left to wonder what type of animal it was built for, or indeed if perhaps this had already been driven to extinction.

Meuris has designed similar vacant enclosures for monkeys, foxes, kangaroos and hippos, according to the exact measurements and needs of the specific species in question. Without an inhabitant these sterile, institutional cages becomes both prisons and stages – and the viewer-turned-voyeur becomes the one held captive by the melancholy scene beyond the glass. p (ew)

Photo: C. Demeter

-

Social Housing

Photography by Dillon Marsh

All photos © Dillon Marsh

-

![]()

Whilst studying Fine Art at the University of Stellenbosch‚ South African photographer Dillon Marsh developed a fascination for the Southern African landscape he had grown up with‚ recalling the numerous trips he had made across the region with his family as a child. In his work Dillon takes a particular interest in the different ways humans and animals leave their structural marks upon the land. His Assimilation series‚ shot in the southern Kalahari Desert‚ showing the nests of the local sociable weaver birds wrapped around telephone poles‚ serves as a perfect example of this focus: “It’s primarily the architecture of the various participants that interests me”‚ he says‚ “I feel there is a lot to be learnt by looking at what humans and animals create and leave behind”.

-

![]()

-

Dillon Marsh graduated from the University of Stellenbosch in 2003 with a BA in Fine Art and has worked with the medium of photography ever since. Primarily a documenter of the changing South African landscape, his work been shown widely in his native country as well as at the Saatchi Gallery in London and photography exhibitions in Paris, Lisbon and Dublin.

dillonmarsh.com

![]()

The sociable weaver bird is unique within the avian kingdom for being the creator of spectacular‚ labyrinthine nests that can hold over a hundred pairs of birds‚ with deep-rooted social and generational hierarchies. Usually these are built in trees but in the absence of plant life in a desert such as the Kalahari‚ a human-made “tree” serves just as well. “I knew only a little about these birds before starting this project”‚ explains Dillon. “My main objective was to express the wonder I felt for the nests – they are incredibly numerous‚ with one on almost every third pole for kilometres on end”. I (fs)

-

![]()

![]()

Crabby Chic

Real estate for hermit crabs

-

The Japanese artist Aki Inomata first began contemplating the strangeness of ownership and territory when participating in an exhibition at the French Embassy in Japan in 2009. In a strange diplomatic deal, the ownership of the land that the Embassy sat on had just changed hands between the French and the Japanese, and the extant building was due for demolition. The ease and arbitrariness with which a site’s national identity had been swapped prompted Inomata to create a series of works reflecting on nationhood through the metaphor of the portable shell of the hermit crab.

![]()

![]()

All images: Aki Inomata’s “Why Not Hand Over a Shelter to Hermit Crabs?” series, 2010-2013. (All photos: courtesy Aki Inomata)

-

![]()

Miniature windmills, churches, and even entire cities jut from the surface of her 3D-printed shells, which are modelled upon CT scans of abandoned crab shells and then recreated in transparent resin. Inomata then allows crabs to inspect the new shelters at their leisure – she says “most hermit crabs don’t even glance at” them, but occasionally one of the creatures finds its dream real estate and settles in.

Yadokari, the Japanese term for hermit crab, means “house borrower”, in other words, one who rents rather than owns. As Inomata puts it: “It seems that the bodies of the crabs don’t identify them, but rather the shelters identify them, like one’s country or property does.” For that reason the wearable architectures she chooses to reproduce are often potent cultural signifiers associated with hybrid belonging and belief systems; in the most recent series of works called White Chapel, the crab shells are adorned with typical Japanese wedding chapels, which are built in the style of western Christian churches – though only one percent of the population identifies as Christian. Apparently some hermit crabs find that contradiction a perfect fit. I (ew)

-

Photo: Jesse Rockwell

Tanks For All The Fish

The building formerly known as the New World Shopping Mall in central Bangkok has had a troubled history since it first opened in the 1980s. The illegal construction work that led to its 1997 closure was then followed by a fire‚ a fatal accident during a partial demolition‚ and the dismantling of several of the building’s storeys – drama enough for any site. And then came the mosquitoes.

Rather unsurprisingly‚ a roofless abandoned mall in a climate as humid as Bangkok’s quickly turned into a something of a new world for an infestation of winged pests. Around 2‚000 local traders reasoned that introducing koi carp and catfish into the stagnant rainwater lake now filling the lower floors of the building might curb the problem. And so then came the fish. Thousands of them. Some fifteen years on‚ the Piscean residents seemingly brought more visitors to the mall than its shopping outlets ever did – so many that earlier this month local authorities fenced off the site and began the process of rehoming the underwater populace in an attempt to stop the growing number of urban explorers wanting a view into the fish bowl. p (fs)

-

![]()

DesignsA short survey of zoo architecture and design

By Ned Dodington

Berthold Lubetkin’s 1934 Penguin Pool at the London Zoo. (Photo © ZSL)

-

![]()

Zoos are strange, wondrous and beguiling institutions. They are instructive and detrimental, culturally specific but universally appealing and architecturally unlike any other constructions. Ned Dodington, founder of expandedenvironment.org and a specialist in design for animals and post-human environments, takes us on a selected tour of zoo design and looks at changing notions of the captive audience.

Zoos are primarily dedicated to the habits and lives of non-human animals, yet the emotions they elicited from us can range from captivation and joy to compassion and sorrow. Beyond the lions, tigers and bears, it’s zoos’ facility to reflect our own humanity that makes them such wondrous places. Many of the lessons learned throughout history in this respect are written on the wall, so to speak, in the landscape, architecture and planning and presentation of zoos – all of which combine to illustrate the human intentions behind the organisation of other animals.

Education, conservation and exoticism: the modern zoo

Collecting exotic animals for exhibition is an ancient practice – there is evidence of a menagerie from 3,500 BC that once existed in the ancient Egyptian capital of Nekhen, or Hierakonpolis – and any history of the zoo would be incomplete without mentioning the story of Noah’s Ark. But today’s zoological gardens, or zoos, trace their first pre-modern incarnations to the aristocratic menageries of the fifteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in Europe that were purely for exhibition.

By the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries the menageries had given way – in the wake of the Enlightenment and changing attitudes about animal life – to the first modern zoos and zoological conservatories. Among the earliest zoos and zoological parks of this period are the Berlin Zoological Garden in Berlin’s Tiergarten by Martin Lichtenstein and Peter Joseph Lenné (1844), the Bronx Zoological Park in New York by George Lewis Heins and Christopher Grant LaFarge (1899), and Whipsnade Park (1928) in England.

-

![]()

»Beyond the lions, tigers and bears, it’s zoos’ facility to reflect our own humanity that makes them such wondrous places«

Berlin's Zoological Garden lion enclosure in 1938‚ separating big cats and humans via a moat. (Photo © Berlin Zoo)

-

At the Bronx Zoo, the American architects Heins and LaFarge created a stately entrance with dozens of large bronze animals to welcome the visitor and animal houses were both more generous and more open. The Tierpark in Berlin is said to have been the first zoo to separate animals from humans with water filled moats instead of fences, giving a greater sense of exposure to the animals; and Whipsnade Zoo, founded for the conservation of animals and their habitats, is a large wildlife reserve where many of the animals are allowed to roam relatively freely in a larger enclosure.

But despite their stately appearances, and humane improvements, these zoos were still primarily designed to exhibit the animals as curiosities and their architecture reflected the status of each city or state rather than the character of the animals enclosed within. Early shifts in this thinking presented themselves in the middle to latter half of the twentieth century in projects like the Penguin Pool (1934), and the Snowden Aviary (1964) both at London Zoo. Berthold Lubetkin’s Penguin Pool there is one of the most celebrated pieces of architecture built by humans for animals. Featuring a modernist double helix slide for the penguins, who were usually photographed waddling down the winding slope, Lubetkin’s creation is a naive marriage between naked formalism and a romanticised version of an animal habitat. The reality was not successful. After renovation in 1987 it became a water feature and the penguins were moved to a more natural habitat

Lord Snowdon, Cedric Price and Frank Newby’s extraordinary aviary at the same zoo, built 30 years later, also attempted to be aesthetically pleasing to humans and acceptable to birds, and was designed so that both humans and birds could at times occupy the same space. Unfortunately, as with the penguin’s slide, the aviary was both difficult to construct and proved a challenge to maintain.

![]()

The Antelope House at Berlin Zoological Garden from 1872, designed by Hermann Ende. (Photo © Berlin Zoo)

-

»It is still JUST a one-way experience of some animals looking at some other animals«

Lord Snowdon, Cedric Price and Frank Newby’s aviary at London Zoo, built in 1964. (Photo © ZSL)

-

Mutualism, naturalism and immersion: late modern zoo enclosures

Towards the end of the twentieth century, zoos became increasingly immersive. The visible construction of animal houses took a back seat to the re-creation and presentation of faux-natural habitats. In contrast to Lubetkin’s or Price’s stark forms, zoo buildings became increasingly camouflaged and integrated with animals, visitors and landscape alike. Bernard Tschumi’s Giraffe Pavilion in the Paris Zoo (part of his 2009 redesign of the entire site), for example, blends environment, fencing and structure into one habitat, creating a statement of synthesis and mutualism without being phoney.

The French architecture firm of Beckman N’Thépé with TN Plus created proposals for the Paris, Helsinki and St. Petersburg, in 2005-6, 2007 and 2010 respectively, for quasi-natural environment renovations where they conceived of the zoo as a total environment within which the visitor becomes immersed and surround by wildness. Similar in a sense to the earlier example of Whipsnade Park, the introduction of the visitor into the animal habitat creates a sense of exposure along with a little frisson of danger and exposure to this animal world.

![]()

![]()

Bernard Tschumi’s plan for Paris Zoological Park treats the site as a collection of “formless” structures. The enclosure housing giraffes, antelopes and ostriches features a wooden filter system‚ designed to give the impression of a vertical landscape. (Photo © Iwan Baan, courtesy Bernard Tschumi Architects)

-

Some animals feeding some other animals at a UK safari park. (Photo: Wikicommons/Robek, CC BY 2.5)

-

![]()

Likewise the Danish architectural team BIG has recently published proposals for Zoopolis, a futuristic model for Givskud Zoo in Denmark. Here the visitors are invited to wander among the animals in small glass pods like a contemporary Jurassic Park…which has slightly worrying implications. But though the architectural camouflage might initially distract or fool the animal and observer into a perception of proximity the clear line between the animal and the human worlds remains – just as it was with Whipsnade’s wall-less safari park of the 1930s. Be it jeeps and cars or glass tubes and floating pods, all continue to reinforce anthropocentric views and objectify the animal life within. It's still a one-way experience of some (humanoid) animals looking at some other (non-humanoid) animals.

BIG’s 2014 Zootopia plan for Givskud Zoo in Denmark aims to create the “freest possible” environment for both animals and their visitors. (Diagrams courtesy BIG)

-

![]()

Immersion, othering and inverted species dynamics: a radical shift in species-thinking

Within the last ten years there has been an explosive resurgence in interest in the lives, thoughts, and status of non-human animals. Studies in the fields of biology, ethology and the humanities have tended towards what has been termed Post-Human or Animal Studies, the effects of which are being expressed in a number of projective and sometimes small-scale alternative zoo proposals.

Currently a growing number of designers are unwilling to merely propose a boundary-less zoo. They seek to expose underlying humanist values dominant in the zoo and to re-centre and re-empower the non-human animals within. Natalie Jeremijenko, Joyce Hwang and Fritz Haeg, for example, each push the definition of zoo into new and unexplored territories. Artist and engineer Natalie Jeremijenko, has created several species-inverting installations, one of which is titled OOZ, an inverted zoo project. With OOZ, Jeremijenko employs robotic animals and electronic devices to create an environment where it is the people on display.

Architect Joyce Hwang’s work similarly upends traditional thoughts about the roles of animals in society and the place of architecture in animal lives.

Joyce Hwang's 2010 Bat Tower (inset) at Griffis Sculpture Park‚ Ashford Hollow Foundation‚ NY and Bat Cloud installed in 2012 at Tifft Nature Preserve‚ Buffalo Museum of Science‚ NY. (Photos courtesy Joyce Hwang/Ants of the Prairie)

-

Ned Dodington is a licensed architect and designer working to develop new practices for biologically inclusive design. He is the founding editor and creative director of The Expanded Environment, a web-based investigation into the performative role of design in ecology. His design research and writings have appeared magazines such as Architectural Design and Bracket Journal and Arts and Culture, and his built work and installations have been exhibited in solo and group shows in Texas and in Minnesota. In 2013 he was named one of six emerging design leaders by The Design Futures Council.

![]()

Installation view of “Animal Estates regional Model Homes #1: New York, NY”, by Fritz Haeg at the Whitney Museum of American Art, NY, 2008. (Photo: Sheldan C. Collins)

Her work with bat habitats, such as her Bat Tower and Bat Cloud demonstrate that designers can design for the particularities of an animal’s behaviour and create spaces that are integral to both human and animal life.

Finally, Fritz Haeg, an artist who also trained as an architect, is interested in eliciting interactions from the animals that are part of our daily lives. One of his more recent installations is of small animal habitats in and around the Whitney Museum in midtown Manhattan to attract and provide respite for other “Manhattan animals” such as the bald eagle, barn owl, wood duck, purple martin, eastern tiger salamander and beaver.

So while it would seem that the human desire to marvel at other animals is constant our understanding and appreciation for them is in perpetual flux. Zoos are undoubtedly enchanting and exciting places. They entertain, educate and, when done well, can humanise their visitors. But in the future, rather than at a park or a place, we might discover that we are already living within a rich, wild and boundless zoo. I

-

Fly Inn

Why would anyone want to provide a five-star retreat for garden-variety pests? Because, quite simply, insects will watch your back if you watch theirs. Given a comfy place to nest in all weather, spiders will eat the mosquitoes, bees will pollinate the daisies and those lovely butterflies – well, they aren’t pests at all are they?

Most bugs aren’t picky, and building a DIY insect hotel from found materials is so easy that it’s been a popular hobby in the European countryside for decades. A few wooden logs or sticks, rolled up paper and cardboard, and a hot glue gun (if you really have to) are enough to construct a holiday home for a variety of native arthropods. Although insect communities are generally more than capable of DIY-ing their own rather superior hives and nests, many insects are solo animals, and some, like solitary bees, don’t build homes for themselves. They just need shelter, and maybe even a bit of social interaction – so if you’re hoping for even more beneficial bugs around, you might consider hosting a singles mixer at the local insect hotel on Saturday nights. p (ew)

The Heimanshof Garden in the Netherlands hosts 20 insect hotels on its grounds. (Photo: Bob Daamen)

-

Homes Without Hands

Instinct or intelligent design?

The nineteenth-century debate on animal architectureBy Irene Cheng

-

![]()

Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, philosophers, natural theologians, and scientists engaged in heated debates over the question: Why do animals build? Specifically, was it instinct or intelligence that propelled spiders, birds, bees, and beavers to construct their webs, nests, hives, and dams? The answer had everything to do with that other burning question: What distinguishes animals from humans?

Before the nineteenth century‚ the dominant view of animal behaviour, inherited in various forms from Aristotle‚ Thomas Aquinas, and Descartes‚ was that animals operated according to innate instincts given by a divine source. The natural theologian William Paley (1743–1805) asserted that the wonders of nature could only be explained by recourse to a higher power. He reasoned‚ “There cannot be design without a designer; contrivance without a contriver”. As prime evidence‚ Paley cited the beehive‚ with its apparent swarm intelligence and its strict social order.

By the mid-nineteenth century the debate over animal instinct had intensified as scientific evidence mounted and as the philosophical and theological stakes increased. In 1868 the American ethnologist Lewis Henry Morgan weighed in with his book The American Beaver and His Works‚ which encapsulated years of research into the beaver genus Castor. Morgan analysed the extensive “net-works” of dams‚ canals‚ and lodges that the animals created‚ postulating that beavers erected them in order to create and regulate water flow through artificial ponds‚ allowing the creatures to flee from land-bound predators into the underwater entrances of their lodges and burrows.

For Morgan, the nature of beavers’ large-scale artificial reshaping of the land demonstrated that their “mental principle” was essentially the same as that of humans and that beavers too possessed faculties of memory, reason, imagination and will‚ as well as passions‚ appetites‚ and even the ability to go mad.

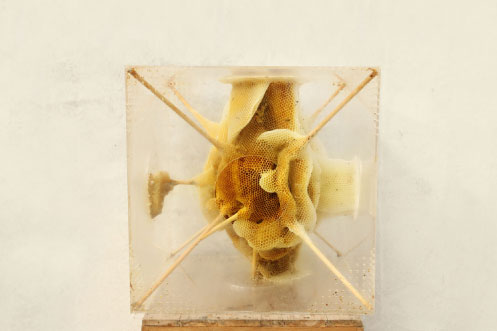

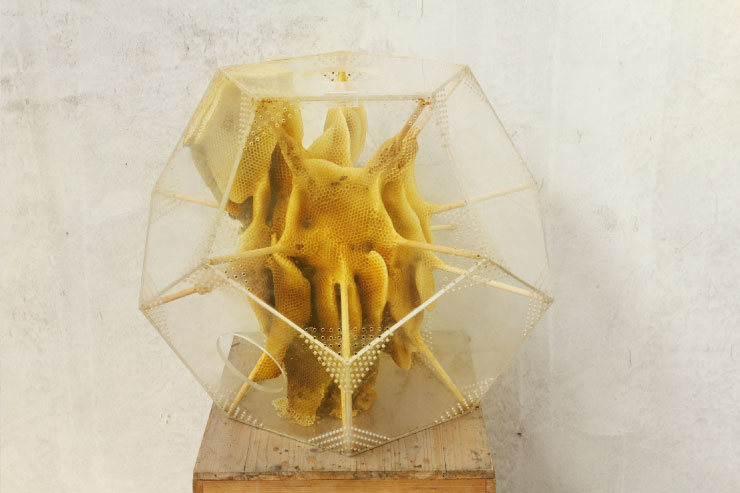

Previous page: “Yuansu II #8-1, 2013-2014”, by Ren Ri. (Photo courtesy Ren Ri)

-

Above all, it was the animals’ ability to adapt their constructions to a variety of site-specific conditions − incorporating part of a fallen tree‚ or fitting a series of dams in a gorge − that demonstrated to Morgan the beaver’s intelligence.

Charles Darwin saw claims about the divine origin of animal instinct as one of the strongest challenges to his developing theory of evolution. Hence‚ he took special pains to develop a counter-explanation for the perfection of beehives in his On the Origin of Species (1859). Darwin adopted the old natural theologians’ idea of “instinct” but replaced the divine cause with a natural one. He argued that the refinement of the bee’s works resulted from natural selection − that is‚ through the accumulation of numerous slight, successive modifications.

Illustration of the Great Beaver Dam at Grass Lake, Michigan from Lewis Henry Morgan’s “The American Beaver”, 1868. (Image: Public domain)

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

Examples from artist Ren Ri’s “Yuansu II”, an artistic collaboration with bees to create complex honeycomb sculptures. Each box is rotated every seven days to allow the bees to build new sections of the work. (All photos courtesy of the artist.)

-

Irene Cheng is an Assistant Professor of Architecture at the California College of the Arts and principal of the multimedia design firm Cheng + Snyder. She is currently working on a book about nineteenth-century utopian architecture in the United States. She is the co-editor with Bernard Tschumi of The State of Architecture at the Beginning of the Twenty-First Century.

A version of this essay first appeared in Cabinet magazine issue 23 (Fall 2006) under the title The Beavers and the Bees.

![]()

![]()

Illustrations showing a prairie dog town and an extensive beaver dam system filling a gorge, both taken from Morgan’s “The American Beaver”, 1868. (Images: Public domain)

The test of fitness was the more economical use of wax‚ which manifested as a geometrically rigorous structure. To support his theory he cited the progressive range of hives‚ from the crude cells of the honey bee to the “perfect” hexagons of the hive bee.

In Morgan’s account, the beaver’s intelligence was seen as directing the activity of building; animal architecture was an expression of consciousness. In contrast‚ Darwin saw the beautiful forms of beehives as accidental‚ the result of agents operating according to natural laws but with no awareness of the means and ends. The differences between the thinkers should not be overstated; in a sense‚ they were like two jousters aiming for the same spot and bypassing each other. Whereas Morgan sought to show that animals had intelligence – akin to humans‚ Darwin was trying to demonstrate that humans operated‚ like animals‚ on instinct. Although Darwin refrained from stating it explicitly‚ the implications of his theory were clear: men were essentially like bees‚ moved by natural forces beyond their control. It was this drone-like aspect of Darwin’s bees that proved most threatening to nineteenth-century sensibilities surrounding the concept of free will. I

-

Photo courtesy Jollice Tan

![]()

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

When the inhabitants of Tashirojima, a small Japanese island in the Pacific Ocean, first brought cats from the mainland to keep the mice population down, they probably didn’t imagine that the felines would one day far outnumber the humans there. Today alongside the roughly 100 two-legged islanders left – mostly over the age of 65 – there live countless stray cats, an animal that in Japan is supposed to bring wealth and good fortune. As a result Tashirojima has commonly become known as “Cat Island”, and various attempts have been made since to leverage this moniker to increase visitor numbers – and income – to the island.

The most prominent of these attempts was the construction in 2000 of a handful of cat-shaped vacation homes, based on the rough sketches of manga artist Shotaro Ishinomori, which were subsequently further decorated with cat drawings. When Japan’s East Coast was hit by the devastating tsunami in March 2011, “Cat Island” was luckily left largely unharmed, although army helicopters had to deliver food for humans and cats in the aftermath. However, sadly the cat-shaped vacation homes have remained closed ever since… I (fh)

Cat crowd photo courtesy Hitek; cat face house courtesy Jasmine T. Blossom; cat-painted house courtesy Jollice Tan.

-

Pigeon Pylon

This brutalist concrete dovecote, designed by Oscar Niemeyer in 1961, is sited on the Praça dos Três Poderes (“Three Powers Plaza”) in Brazilia, where the National Congress, Supreme Federal Court and Presidential Palace are all located. It seems at first a strange structure to include at the centre of national power, but the tradition of building elaborate structures to keep pigeons and doves dates back to Ancient Egypt and Persia, where they were prized for their eggs, flesh, and fertilising dung. This tradition continued in Europe, where the possession of a dovecote became a status symbol: in Ancien Régime France only nobles were granted the privilege to keep doves.

Since Noah, the dove has been associated with hope, peace and freedom of the spirit, appropriately symbolic for a democratic capital, but Niemeyer’s inclusion of a dovecote here may also have been a form of one-upmanship on Le Corbusier. For while the latter had designed a sculptural open-hand-as-dove motif at Chandigarh, here it is real doves that animate (and mark/splatter) the plaza with their presence, while physically the dovecote’s textured concrete form, like an inversion of a Brancusi endless column, punctuates the open expanse of the plaza like an exclamation mark. I (rgw)

Photo: © Leonardo Finotti

-

Down

![]() on the

on the

FarmGood design for livestock

All animals have the right to adequate shelter and good care, and this month’s focus selects four architectural projects for farm animals that show good design shouldn’t begin and end with our own homes.

-

![]()

![]()

Denmark hasn’t had the best of records in the past when it comes to factory farming, but Danish architects LUMO have placed the well-being of animals at the forefront of the building concept for their Velskovgård barn in the farmland of Odder just south of Aarhus. The design of the 8,000-square-metre interior abandons depressing stalls for an open star-shaped plan, which accommodates 600 milk cows – over 14 square metres per cow – and every position within the building allows broad sightlines inside and out. Situated sensitively amongst the low rolling hills of the surrounding farmland, light streams into the peaked windows during the day and shines out like a beacon after dark. As a partnership between a family farm and the Danish building fund Realdania Future Agriculture Construction, the Velskovgård stable is intended as a beacon of light for the future of farming. (ew)

(Photos courtesy LUMO Architects)

-

![]()

![]()

Fifty kilometres south of Prague lies a farmstead in the town of Semtín. Built in the late nineteenth century, the land and buildings have lain empty since the 1980s – that is, empty but for a population of storks nesting on the chimney of its former distillery.

When architects SGL Projekt were commissioned to redesign the farm in 2006, the diligent, methodical and practical architecture of the storks became the main symbolic driver of their plan. So in addition to constructing a reception centre, hotel, conference hall, restaurant, pool, bowling alley, private house and new farmyard, they also designed a circular riding arena based on a stork nest.

With a diameter of 34 metres and height of 12.5 metres, the building is not only a place for horse training but also for presentations and cultural events.

While not exactly constructed according to the stork’s methods or materials, the arena is decidedly more weatherproof. Its timber support structure is clad with translucent polycarbonate (allowing light to enter the space) and then covered with 200 tonnes of oak logs for shade and for shape. It certainly looks like a nest, but there’s no way to know exactly what storks – or indeed horses – think of it. (ew)

sglprojekt.cz(Photos: Jaroslav Malý‚ courtesy SGL Projekt)

-

The 750-acre Hadspen estate in Somerset, England has belonged to Niall Hobhouse’s family since the late 1800s. The main farmhouse dates back to 1689. Intending to return the landscape and its buldings to (a version of) its former glory after a period of neglect, Hobhouse has spent the last decade commissioning architects to add and restore structures. The first to be realised was a new cattle barn by Stephen Taylor Architects in 2012.

The 42 x 20-metre barn is an interesting mix of the classical and the vernacular and surprisingly grandiose for such a humble building. It is distinguished by its two arches, one edged in raw timber and the other sculpted in a raw, rough, stratified concrete that looks like marble from a distance, but more like stamped earth at close quarters. Coupled with this is a colonnade along one side of perfectly cylindrical concrete pillars supporting the angled roof, which spans a rather mundane prefab steel animal shed giving the whole structure an oddly po-mo vibe – sort of folly meets functional.

Stephen Taylor Architects are currently working on a brick hay barn for the same estate. (ew)

stephentaylorarchitects.co.uk![]()

![]()

Photos courtesy Stephen Taylor Architects.

-

![]()

![]()

(Photos courtesy Chris Mullaney)

Origami purists, rejecting any cutting, glueing, or marking when folding creations out of paper, stick closely to the goal of the Japanese art: finding an elegant solution that uses the whole material without any scraps. In the spirit of that tradition, Australian architect Chris Mullaney pulled off a clever folding technique on a large scale – using galvanised steel rather than paper.

Mullaney built this corrugated coop for his parents’ six chickens, housed in their backyard in Stroud, Australia. The folded steel mesh framework and standard plywood sheets he employed are charmingly low-tech, but are also durable materials that afford an inexpensive, repeatable, and sustainable design. A plywood offcut from the chicken doorway is recycled to create an eave for rain, and the straw lining the dormitory is recycled in the nearby vegetable garden. The coop’s six hen residents can now slumber safely atop their specially designed nesting boxes, protected from foxes but integrated into the surrounding environment. Didn’t some wise person say that happy hens lay tastier eggs? (ew)

chrismullaney.com.au -

![]()

![]()

![]()

The Final Indignity

In 2011 Italy’s Armin Blasbichler Studio ruffled some feathers within the design world when it produced the Orson collection — a series of tables that took taxidermy as its primary material (dead deer, sheep and pigs, to be precise). However, as the vintage images here demonstrate, the Victorians had embraced the idea with characteristically gruesome panache over a century earlier, at a time when Man’s inhumane treatment of Animal reached new heights.

First published in an 1896 edition of London’s The Strand Magazine, author William G. Fitzgerald introduced a myriad spread of imperial souvenirs across an eight-page article entitled “Animal Furniture”, including a bear shot by the then-Prince of Wales which was reincarnated as a (very) dumb waiter; the Princess of Wales’ favourite parrot given new purpose as a fruit and flower stand, and (how appropriate) a man-eating tiger armchair, belonging to a member of the Civil Service.

Given that Fitzgerald describes the process of turning such beasts into “articles of furniture and general utility” as both “ingenious and praiseworthy” one can’t help but wonder about the fate of “Punch”, the very-much-alive little Highland Terrier pictured sitting on a chair which had been, once upon a time, a baby giraffe. If you’re still curious, take a seat and read much more on the Victorian “nose-to-tail seating” phenomenon in this blog article! p (fs)

![]()

Photographs courtesy University of Sheffield Library.

-

The Silesian Museum, Katowice by Riegler Riewe Architekten (Photo: Wojciech Krynski)

![]()

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Intelligence starts with improvisation.«

Yona Friedman

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents