-

Magazine No. 34

Commune Revisited

-

No. 34 - Commune Revisited

-

page 02

Cover

Commune Revisited

-

page 03

Editorial

Commune Revisited

-

page 05 - 12

Communities of Consciousness

From Drop City to the digital by Fred Turner

-

page 13 - 14

New Harmony

(1825-1827)

-

page 15 - 17

Arthouse Revival

Xucun, China

-

page 18 - 25

On Cooperation

An interview with Richard Sennett by Rob Wilson

-

page 26 - 27

Let’s Get Gated

International Residential Complex Rosinka, Moscow

-

page 28 - 29

The Paris Commune

(1871)

-

page 30 - 37

A Natural Order

Photographer Lucas Foglia portrays outsider life in rural America

-

page 38 - 39

The People’s Commune

(1958-1983)

-

page 40 - 41

The Mothership

Auroville, Tamil Nadu State, India

-

page 42 - 48

The Rule of Hours

James Marriott on Hans van der Laan's Abdij Sint Benedictusberg

-

page 49 - 50

Eco Beach

Lima, Peru

-

page 51 - 55

Enduring Concensus

Malcolm Miles on Freetown Christiania at forty-three

-

page 56 - 58

Connected Communards

Mount Telaithrion, Euboea, Greece

-

page 59 - 62

In the Photo Booth with...

Piet Hein Eek

-

page 63

Klaustoon

XXIV. Fifty years inside the bubble

-

page 64

Next

Bricks

-

-

uncube’s editors are Sophie Lovell (Art Director, Editor-in-Chief), Florian Heilmeyer (fh), Rob Wilson (rgw) and Fiona Shipwright (fs); editorial assistance: Sara Faezypour (sf); graphic design: Lena Giovanazzi; graphic assistance: Diana Portela.

uncube is based in Berlin and published by BauNetz, Germany's most-read online portal covering architecture in a thoughtful way since 1996.

One year after our Urban Commons issue, we’re returning to the idea of the communal, this time investigating just how diversely the concept of “commune” can be interpreted – and not always with entirely benevolent intentions or successful results.

Whether trying to escape a broken economy or an oppressive system via new forms of existence or looking to break the system itself via anarchic methodologies, forming a commune traditionally involves segregation or stepping “outside” society.

But no matter how off-grid and back-to-nature the contemporary communities that we investigate here are, it turns out they are far more connected than we think.Turn on, tune out, drop in.

Cover image: Andrew and Taurin drinking raw goat's milk, Tennessee, from “A Natural Order” by Lucas Foglia.

-

Communities of

ConsciousnessFrom Drop City to the digital

By Fred Turner

Photo: Richard Kallweit

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Contrary to popular belief, the New Communalists of the 1960s didn’t just drop out, they embraced technology in such a way as to influence the core attitude behind the biggest commune of all: the internet. But the reality was not as liberated and utopian as it seemed. Stanford professor and author Fred Turner relieves us of our rose-tinted spectacles.

In the summer of 1965, a ragtag handful of long-haired young men ambled into a Colorado junkyard with axes in their hands. One after another they climbed onto the tops of broken-down sedans and station wagons and began to hack away at their roofs. The junkyard owner charged them fifteen cents for each sheet of metal they managed to chop free. Every evening, they hauled their car tops home and cut them into panels, which they welded into what soon became a village of multi-coloured geodesic domes, perched on the open plains.

The village was called Drop City and it quickly became one of the most visible American communes of the 1960s. It also became a beacon to many who have designed our digital world. The Droppers, as they called themselves, were part of the largest wave of commune-building in American history. Between 1965 and 1973, historians estimate that as many as 600 communes were built across the United States and that 750,000 Americans took up communal living. These mostly young, white, middle class communards had extraordinary faith in technology, in themselves, and above all, in the power of design to replace conventional politics. Their example has long animated such leaders of California’s computing industry as Apple’s Steve Jobs and Google’s Larry Page and Sergey Brin. Yet, the communes of the 1960s were far from utopias. On the contrary: their failures should alert us to how badly misplaced our contemporary faith in design and in digital technology might be. -

“Kids, tear the top off your daddy's car...

-

»Properly arranged, the technologies of mainstream America could bring about utopia... a world in which each person could be connected to every other, without politics, in a state of perpetual fraternal intimacy.«

...and send it, together with 10 cents in cash or coin, to Drop City, Colorado.” (Photo: Clark Richert)

-

To understand why, we need to return to the America of the late 1960s. In popular accounts, the American hippies of the time marched against the Vietnam War during the day and dropped acid at night. Radical politics and alternative lifestyles were two sides of the same coin. In fact though, there were at least two distinct movements within the counterculture. The first, the New Left, did politics to change politics. Its members formed parties, organised committees, marched.

The second, which I will call the New Communalists, turned away from politics and toward consciousness as the engine of social change.

In his 1968 book The Making of a Counter Culture that first popularised the term “counterculture”, historian Theodore Roszak put the New Communalist vision thus: “building the good society is not primarily a social but a psychic task”. Like many who grew up in the shadow of the nuclear bomb, the New Communalists loathed large-scale technologies and the bureaucratic society that had built them. But they had also come of age alongside an unprecedented array of consumer technologies – inexpensive automobiles, portable radios, surfboards, electric guitars.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

»On the actual communes of the 1960s, the turn away from government and toward technologies of consciousness rarely resulted in liberation.«

-

Rather than abandon these delights, the New Communalists declared them tools with which to alter their minds and so society as a whole.

Designers were to take up these products of industrial society and working with their hands, turn them into tools that could in turn support communities of consciousness. Properly arranged, the technologies of mainstream America could bring about utopia: to dance under psychedelic lights, with the howl of electric guitars circling through the air, offered many what they thought was a glimpse of a world in which each person could be connected to every other, without politics, in a state of perpetual fraternal intimacy.

Their founders dreamed that communities of consciousness would multiply, metastasise, and transform every corner of American life. Today, at least according to the leading makers of American digital technology, they have.

Though the communes of the 1960s almost all collapsed within a few years of their founding, executives at Apple and Google and Facebook, among many other firms, continue to promote computing in New Communalist terms. As Apple’s co-founder Steve Wozniak put it recently, “We created the computers to free the people up, give them instant communication anywhere in the world; any thought you had, you could share freely…[It] was going to overcome a lot of the government restrictions.”

Recent revelations of the American government’s digital surveillance programmes have revealed the depth of Wozniak’s naiveté. But the problem isn’t so much one of digital technology as one of our faith in design.

On the actual communes of the 1960s, the turn away from government and towards technologies of consciousness rarely resulted in liberation. On the contrary, it revivified the prejudices of mainstream America. In the late 1960s, many rural communards imagined that they were pioneers, setting out for unsettled lands.

Photo: Richard Kallweit

-

![]()

Extract from the “Drop City” documentary film directed by Joan Grossman, 2012. (Film © Seventh Art Releasing)

-

Fred Turner is an Associate Professor of Communication at Stanford University and the author of several books, including The Democratic Surround: Multimedia and American Liberalism from World War II to the Psychedelic Sixties (University of Chicago Press, 2013) and From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network and the Rise of Digital Utopianism (University of Chicago Press, 2006).

fredturner.stanford.edu

A slightly longer version of this article was first published in form magazine, issue 249, Sept/Oct 2013.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Stills from the documentary film "Drop City".

In fact, they often built their communes amongst Native American and Mexican-American communities that had been there for generations. Few New Communalists reached out to these groups. Rather, like the suburbanites they claimed to despise, many stayed within the bounds of their own carefully designed communities, among their own demographic kind. Likewise, when communes did away with the political process of rule-making and representative negotiation, they often re-empowered the most conventional forms of sexism. For all the talk of “free love” in the sixties, rural American communes tended to privilege heterosexuality and male sexual freedom.

This history offers us a warning. Seated behind our computer screens, on Facebook say, or some other social network, we are in touch with one another via invisible electronic signals and we seem to enjoy the sharing of consciousness promised by communal living. Much as the Droppers once repurposed the automobiles of American industry, we have transformed the computers of the military-industrial-academic establishment into tools for a kind of disembodied intimacy. But with whom are we intimate? Do we reach out to those with whom we most disagree? Do we travel across the boundaries of race and gender and nationality? And what kinds of communities do we build when we do?

![]()

-

NEW HARMONY

(1825-1827)

The envisioned New Harmony commune in an 1838 engraving by F. Bate. (Public domain)

-

In 1825 Robert Owen, a Welsh philanthropist-turned-socialist, bought the town of Harmonie, in the region then known as Indiana Territory, in its entirety. He then attempted to create a commune of 3,000 people there, living and working (harmoniously) within a projected giant, socialist citadel, which would have been the largest structure in the country.

Owen rechristened it “New Harmony”, envisioning a vast quadrangle which would act as a prototype for settlements across the continent and indeed the globe, enabling the creation of a “New Moral World”. The inaugural structure was set to cover three acres and encompass all the components needed to bring about communal utopia: dwelling space, schools, segregated bath houses, communal kitchens and dining halls, ballrooms, lecture theatres, “dormitories for the unmarried”, a bookbindery – even a brewery.

So serious were Owen’s intentions that he even presented a model of the model society at the White House. But the experiment would ultimately fail. The principle of united interests brought a concommitent sense of diminished individuality, causing many less-ideologically driven residents to abandon the experiment. Quarrels ensued and the commune descended into chaos. However New Harmony’s legacy has endured, notably in the USA’s free public library system, first initiated in the town, and also apparently in the phrase ‘free love’, coined by Owen to describe his alternative to the oppressive institution of marriage. p (fs) -

![]()

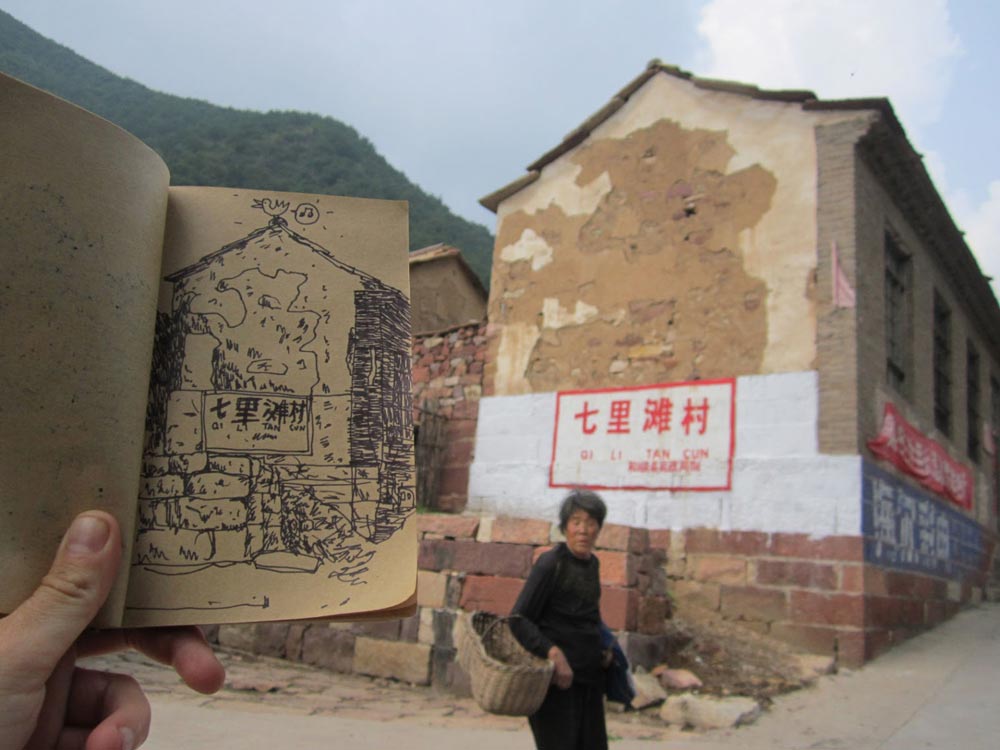

Arthouse Revival

Xucun, China

-

Establishing residencies for contemporary artists in isolated areas has become a common regeneration tool, attracting new life and even generating some profit. However when artist outsiders land UFO-like to partake in the picturesque rural life, the economic benefits don’t always trickle down to locals. So the artist Qu Yan decided to try to establish a more truly “commune”-style residency model in Xucun in eastern China.

Deep in the Taihang Mountain range, this 2,000-year-old traditional farming village is relatively cut off from all types of infrastructure, and its population of around 1,600 has been diminishing as young people leave for distant mining towns and urban areas. In turn, its unique architecture – some of which dates back to the Ming and Qing dynasties – is disappearing due as much to lack of resources as lack of pride.Previous page and this page: once abandoned depots now house the commune's office and conference room. (All photos: Xucun International Art Commune)

-

![]()

Supported by the Heshun County Secretary of the Communist Party, Fan Naiwen, Qu Yan resolved to devise a programme that could help invigorate the community through the arts. Thus the Xucan Artist Commune was born, a biennial artist residency accompanied by an arts festival, which in its first two cycles has seen around 50 artists (half Chinese and half international) arriving in Xucun to live with locals in their homes.

Each artist is provided with an interpreter to bridge the language gap, and their projects have included collaborating with artisans to learn calligraphy, traditional paper cutting and teaching kids to draw. Meanwhile several buildings have been restored, including one used as an exhibition space.

Despite Qu’s hopes of reviving the community in the long term, in this case it’s actually the residency’s iterative, impermanent structure that allows it to stay independent. As assistant curator Jo-Yu Lin explains: “it would be very difficult for a [permanent] private cultural institution to survive without the support of the government and CPC”. Unlike certain historical commune-ism-s aimed at solidarity through uniformity, the goal of Xucun is to create community through difference. “We believe in a communal living style that is created and led by art”, adds Jo-Yu, “Art will serve as the catalyst for face-to-face interaction that helps people to go beyond the barriers of languages and culture.”![]() (Elvia Wilk)

(Elvia Wilk)Artists respond the landscape and inhabitants of Xucan in a variety of ways.

-

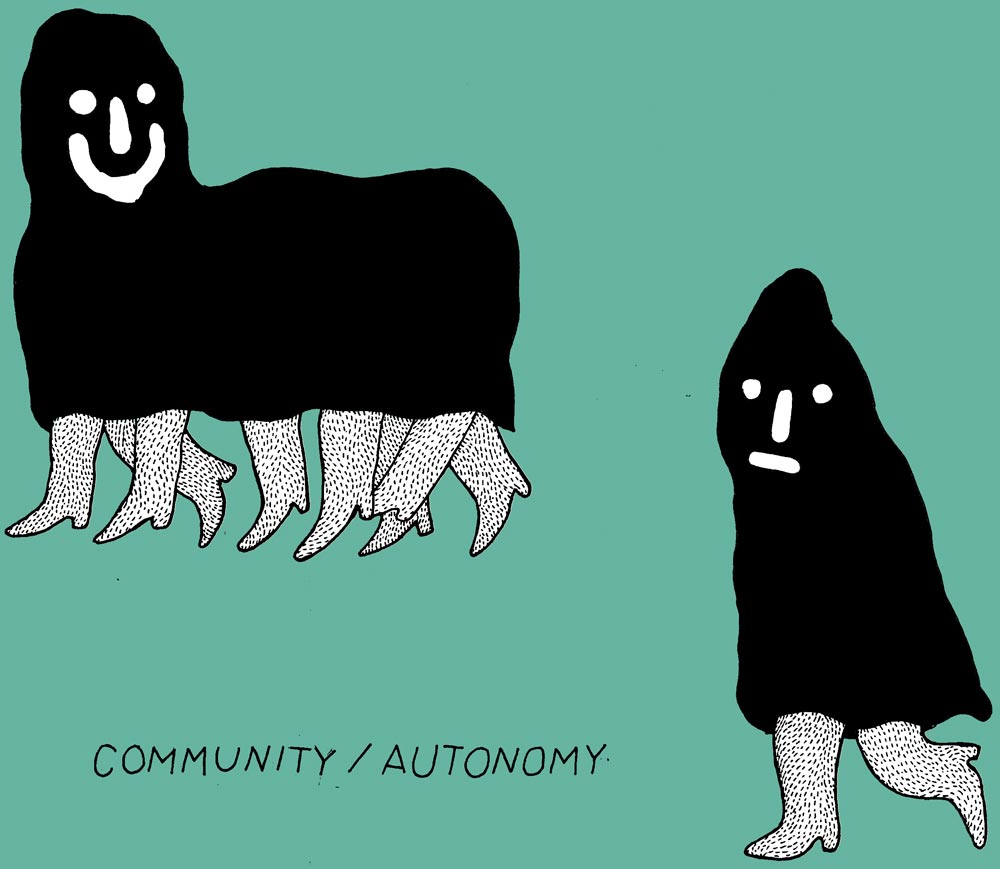

![]()

An interview with Richard Sennett

By Rob Wilson

Illustrations by Tomba Lobos

-

Rob Wilson spoke with the urbanist and sociologist Richard Sennett about whether the idea and ideals of the “commune” as a model are relevant in being revisited today – particularly against the background of the economic crisis. For Sennett it is clear that it is not communes we need to look at, but cooperation itself...

![]()

-

In your book Together you explore aspects of bottom-up cooperation – including looking at past examples of self-sufficient communities founded on cooperative principles, like Robert Owen’s New Harmony in Indiana in the early 1800s – and relating this to current ideas. Do you see the communal or commune-type model as having a new relevance, in particular in cities today?

Well, the original commune, the Paris Commune of 1871, was a reaction to military invasion. The self-sustaining idea there came about because the Communards were surrounded by German troops. So it was not a voluntarily cooperative thing – which is one thing that gets forgotten – people needed to cooperate or they were going to starve to death, which they nearly did anyway. So in a way it’s not a really good example. And Robert Owen is not a good example either, because New Harmony was an anti-urban, idealised community where people could be self-sustaining by leaving the city.What interests me is, if you are in an urban situation where the threats are economic rather than violent, what kind of cooperation can you engage in?

We really have to understand where the State is likely to fail people in order to understand what kind of bottom-up cooperation is needed. David Cameron’s “Big Society” in the UK is really a very corrupt version of that, with the Tories saying: if I take everything away from you, if I cut everything and deprive you economically, then you are on your own – then see if you can still survive. And that’s not a situation that we want to be in. -

So cooperation is where we need to start?

We need to have cooperations and communities based on the idea that we can structure power bottom-up and create a state out of them. We have to look at cooperation as an activity that happens in civil society but that doesn’t do away with the State. That is what the right-wing wants to do: to do away with the State. And that to me is horrible politics.![]()

-

My book Together was about the question: how do people cooperate well? What kind of skills do you need to be able to cooperate with other people, particularly with people who are different from you? That’s an urban thing. If you are white and you have to work with black people, what kind of skills do you need to cross that racial boundary? Or gay and straight – you can spin it out any way you want.

The fact of cooperation is a starting point. And what I’ve argued is that we are not very skilled in ways of cooperation. We’re very assertive: the language we use is declarative rather than tentative, or subjective. There are a whole set of things we need to address about being able to communicate with other people that crosses barriers of difference.Going back to politics, I am interested that you’ve made the point that there have also been issues on the Left in regard to cooperation, particularly with how the socialist ideal ended up being top-down solidarity, not bottom-up cooperation. Do you see ways in which this can be avoided in the future?

“Solidarity” is a term of power. It is the idea that everybody is on the same page, that there is a repression of differences between them, a repression of debate. Solidarity is a repressive idea, so my big argument about it is that we need to relearn cooperation and unlearn solidarity.

When Socialism got going in the nineteenth century, the cooperative ideal was much stronger. It was only after the First World War that the idea of it as a revolutionary vanguard developed. And then in China under Mao Tse-tung there was this idea that solidarity means that there is no distinction: that there is no distinction of dress, of language, that people mature at the same rate, a tyrannical form of sameness. We don’t want that! -

So what do we want cooperation to be?

If we want alternatives, then we need to know how to deal with differences. Take labour organisation. Often when you need to work with very different groups of people, one of things that you have got to admit to yourself is that you don’t understand what the others want. But they want it and we’re comrades and we want to work together. Accepting the idea of “not getting it”, that there are limits to your own understanding – that is a way of cooperating with someone else by accepting that there are those limits. In a regime of solidarity, nothing is foreign to you; you understand everything.![]()

-

![]()

-

Richard Sennett (*1943, USA) is a sociologist and urbanist who writes on cities, labour and culture. His research entails ethnography, history, and social analysis and theory.

He studied at The Julliard School of Music, the University of Chicago and Harvard University and is University Professor of the Humanities at Harvard, Professor of Sociology at the London School of Economics and Director of Theatrum Mundi, a forum for cross-disciplinary discussion about cultural and public space in the city.

His books include The Fall of Public Man [1977], a study of the public realm of cities; Flesh and Stone [1992], a study of bodily experience and the evolution of cities; and The Culture of the New Capitalism [2006], looking at change in the work-world and its consequences for workers. Most recently, he has explored more positive aspects of labour in The Craftsman [2008] and Together: The Rituals, Pleasures and Politics of Cooperation [2012]. The third volume in this trilogy, The Open City, will appear in 2016.

richardsennett.com

In terms of urbanism, can you transfer ideas of bottom-up self-organisation effectively to the city, which seems to need by its very nature to have a top-down structure?

You can have both. You couldn’t get an electricity grid in the city by bottom-up cooperation – not yet at least – nor a sewer system. But schools can work bottom-up if they have the resources. If the State gives you the money, then you can self-organise. But particularly in poor communities you often don’t have the resources that allow you to cooperate.And what about architecture?

You mean could we produce cooperative architecture? Everybody believes in co-production, but it’s not that simple. If you have got 15 or 20 years of design experience under your belt you don’t want to say to people: forget experience, lets cooperate. You want to show what your knowledge is. And at that point, because you have knowledge and they don’t, it’s an asymmetrical relationship. This is a real issue in urbanism.

Architects’ offices don’t work as communes. I know architects who say they are very collaborative and all the rest of it, but in the end, there is someone who says yes or no. And maybe this is because you have this building, which is a fixed object. Maybe the object is the limit of cooperation. IPhoto: Thomas Struth

-

![]()

Let's Get Gated

International Residential Complex Rosinka, Moscow

Images courtesy International Residential Complex Rosinka

-

![]()

A. Main Entrance, B. Second Entrance, C. Tennis Courts and Skating Rink, D. Kindergarten, E. Head Office, Community and Sport Centre, Property Management, Minimarket, F. British International School, G. European Medical Centre, H. Beach, S. Main Security Post.

x Neighbourhoods x Children’s Playgrounds

Ahh. This is how it could be: a perfect green lawn in front of your nice new house. The peace! The quiet! The sweet safety of social coherence!

On hearing about your new job in Moscow you were admittedly a little nervous. But then you found “Rosinka”. A gated community built in 1990, your new home takes its name from the Russian word for “dewdrop”. It may be just 20 kilometres from the city centre, but it’s surrounded by national parkland and a Federal Russian Forest Reserve, leaving you far, far away from the noise and buzz of the Moloch.

For your new dwelling, you could choose from between five different housing types: “Executive” (three bedrooms, three bathrooms, garage for two cars) for instance, or “Presidential Deluxe” (five/five/two plus sauna).

There is a supermarket, sports centre, lake, beauty salon, medical centre, spa and international school for the kids – all private and all within ten minutes walking distance.

The property management is available 24/7, as is the private security service: “One of the main priorities of Rosinka is safety”, the brochure reassuringly informed you, explaining that “there is a 24-hour security service supported by an advanced electronic safety system: the territory of our community is guarded by the state-of-the-art tracking systems and sensors.”

You can barely see the fences from the lawn and the kids quickly learned that they should not leave the complex. Indeed you found yourself realising that, work aside, there is barely any reason to leave this paradise at all...![]() (fh)

(fh) -

The Paris commune

(1871)

Communards at the barricades, 1871. (Photo: public domain)

-

This, the most celebrated, defining example of a commune, saw the City of Paris run as a revolutionary proto-socialist state for two months in 1871. It followed the messy endgame of the Franco-Prussian War, when, after French defeat at the Battle of Sedan in September 1870, the Third Republic was proclaimed, and fighting continued, only to see Paris besieged for four months, its residents reduced to eating rats. Finally in January 1871, the provisional French government sued for peace.

In the power vacuum that followed, the National Guard in Paris, dominated by left-wing revolutionaries, seized power and a red flag was hoisted over the Hotel de Ville. Elections held in March, resulted in a new Commune Council consisting of nine committees and with no single leader. A flurry of decrees followed, abolishing the death penalty, dividing Church and State, regulating working hours and establishing free schooling, while steps towards the emancipation of women began, with demands for gender and wage equality.

However, in late May the army moved to reconquer Paris, and in “the Bloody Week” that followed at least 7,000 “communards” were summarily executed. But though the Paris Commune collapsed quickly in failure, it was hailed by Karl Marx as a “dictatorship of the proletariat” – a step towards the hoped-for classless society to come. I (rgw) -

A Natural Order

Outsider life in rural America

Photography and words by Lucas Foglia

Homeschooling chalkboard, Tennessee.

-

Between 2006 and 2010, the photographer and artist Lucas Foglia travelled throughout the southeastern United States photographing and interviewing a network of people who left cities and suburbs to live off the grid.

Jasmine, Hannah and Vicki picking jewelweed, Tennessee.

-

Family portrait with the photograph George took of Christina at their wedding, Tennessee.

-

» I grew up with my extended family on a small farm in the suburbs of New York City. While malls and supermarkets developed around us, we heated our house with wood, farmed and canned our food and bartered the plants we grew for everything from shoes to dental work. But while my family followed many of the principles of the back-to-the-land movement, by the time I was eighteen we owned three tractors, four cars and five computers. This mixture of the modern world in our otherwise rustic life made me curious to see what a completely self-sufficient way of living might look like. «

General store, Tennessee.

-

» Motivated by environmental concerns, religious beliefs or the global economic recession, these people chose to build their homes from local materials, obtain their water from nearby springs, and hunt, gather, or grow their own food. «

Patrick and Anakeesta, Tennessee.

-

» All the people in my photographs are working to maintain a self-sufficient lifestyle, but no one I found lives in complete isolation from the mainstream. Many have websites that they update using laptop computers, and cell phones that they charge on car batteries or solar panels.«

Creek, Kevin's land, Virginia.

-

![]()

![]()

Todd after a haircut, North Carolina; Tod’s vegetable oil van, North Carolina.

-

Lucas Foglia (b. 1983) grew up on a family farm in New York and is currently based in San Francisco. He graduated with a MFA in Photography from Yale University and with a BA in Art Semiotics from Brown University. His photographs have been widely exhibited in the United States and in Europe, and are in the permanent collections of museums including the Denver Art Museum, Museum of Fine Arts Houston, Philadelphia Museum of Art, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and Victoria & Albert Museum, London. Foglia’s first monograph, A Natural Order (Nazraeli Press, 2012), and his second monograph, Frontcountry (Nazraeli Press, 2014), were published to international critical acclaim. He is represented by Fredericks & Freiser Gallery, New York and Michael Hoppen Contemporary, London.

lucasfoglia.com

National Geographic, Wildroots homestead, North Carolina.

» They do not wholly reject the modern world. Instead, they step away from it and choose the parts that they want to bring with them. «

-

the People’s commune

(1958-1983)

Image: Chinese Poster Collection, International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam.

-

The idea of communing may typically involve a retreat from the state system, but that doesn’t mean states haven’t also tried making a system out of the idea. In Mao-era communist China, as part of the “Great Leap Forward” of the 1950s – the campaign that led to the Great Chinese Famine – the notion of the commune was developed from mutual cooperation into a utopian apparatus of production on the grandest scale. “Many rural communes will surround the cities, making for even larger communist communes. The notion of utopia mentioned by our predecessors will be realised and surpassed”, state official Lu Dingyi told a party congress of the time.

With impossibly outlandish production targets being met by even wilder claims of their fulfilment, the sense of (politically cultivated) competition amongst APCs (Agricultural Producers’ Cooperatives) spurred them into joining forces with others in their locale. Eventually whole provinces became single cooperative units of up to 10,000 people, counting not just grain, but schools, hospitals and factories as part of their output. The People’s Commune became state policy in 1958: the name proposed by Mao Tse-tung himself, who liked how the phrase encompassed the façets of industry, agriculture, military and livelihood – all in the servitude of political power. p (fs) -

![]()

The Mothership

Auroville, Tamil Nadu, India

The Matrimandir, Auroville. (Photo: Wikicommons/Santoshnc, CC BY-SA 2.5)

-

Originally founded in 1968 by the spiritual visionary Mirra Alfassa, known as “the Mother”, Auroville (The City of Dawn) is an idealistic, universal township on the south-eastern coast of India. Supported by the Indian government, the stated purpose of this utopian community is to “realise human unity – in diversity”, through a “transformation of consciousness” and research into sustainable living and humanity’s “future cultural, environmental and spiritual needs”.

The underlying concepts of the community are embodied in its architecture and town planning by the French architect Roger Anger. At the centre lies the Matrimandir, or “Soul of the City”, a golden spherical temple rising from the earth, which took 37 years to build, and was completed in 2008. In its pure form, it echoes platonic 18th century ideal architecture, but its outer surface of decorative golden disks has more a sci-fi-like feel. The interior is stripped of ornament, a space intended for contemplation and reaching inner peace.

Auroville’s masterplan reflects “a galaxy in which several ‘arms’ or lines of force seem to unwind from a central region”. Four main zones radiate from the centre: residential, industrial, cultural, and international, all enclosed by a green belt. But as the Mother once said: “Apart from these lines of force, everything is flexible, nothing is fixed.” Today, half a century on, Auroville describes itself as: “a culture still to be invented”.![]() (sf)

(sf)![]()

![]()

Top: The galaxy concept of the city’s masterplan: a macrostructure model dating from early 1967. (Photo source: Auroville) Bottom: details of the Matrimandir (Photos: Manohar Luigi Fedele)

-

The Rule

of HoursAbdij Sint Benedictusberg

By James Marriott

-

![]()

Artist and activist James Marriott reflects upon the acts of communing undertaken by an order of Benedictine brothers, and how they are shaped by a monastery designed by the architect and monk Hans van der Laan.

The Abdij Sint Benedictusberg is a community of Benedictine monks that was established in an abandoned monastery near Maastricht in 1951. The abbey is utterly focused on the life of prayer, expressed through eight daily services – the Hours – in which the psalms are sung, starting at five o’clock in the morning and ending at nine o’clock in the evening.

The abbey, like all Benedictine houses, strives to keep as close as it can to the Rule of St. Benedict, a book of precepts written in about 540 AD by St. Benedict of Nursia that has been continually observed in monasteries ever since. The Rule precisely describes an ideal Christian community as seen by a man living at the point of transition between the Classical World and the Medieval World. For guidance, St. Benedict looked to the communities of the Early Christian Church, as portrayed in the Acts of the Apostles written nearly four centuries earlier. Consequently, the monks at Sint Benedictusberg today try to live up to a vision of community that is two thousand years old. They orient their imaginations towards an idealised vision of Christ created by those who followed soon after him.All photos: Flickr/ Jason John Paul Haskins (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

-

»In the most remarkable way, light becomes solid matter as it falls into the silent rooms and passageways.«

-

The sense of this unchanging continuity is emphasised by the language in which the community expresses its central activity. Despite being located in the Netherlands, where all the monks speak Dutch, almost the entirety of the daily services is sung in Latin. Similarly, the reading given to the brothers as they eat their midday and evening meals in silence is partly in Latin. This language, in which the Medieval Church expressed itself, is a foundation stone of the shelter that the monastery provides for those that live there. The monks learn Latin upon joining the monastery, and through it they give order to their world.

Sint Benedictusberg is famed for its architecture. Most of it was built between the 1960s and 1980s, designed by the architect Hans Van der Laan – who throughout that period was a brother in the abbey itself. The simplicity of its form, with square windows and unadorned pillars, is heightened by uniform grey paintwork and a grey skim of cement on all the internal walls. Every piece of furniture – tables, chairs, pews and beds – was built from wood in the abbey workshop according to Van der Laan’s designs. His style gives each object a heavy solidity, which echoes the structure of the buildings. In the most remarkable way, light becomes solid matter as it falls into the silent rooms and passageways. In a place where there are so few objects, the material quality of the world is acutely highlighted.![]()

-

»Life in the abbey is like living in a human clock.«

-

The consistency of the aesthetic serves to emphasise the distinctness of each type of space: the cells, the chapel, the refectory and the cloister. St. Benedict’s Rule demands that spaces within the monastery should be precisely delineated, and that the distinct activities of the day are to take place in the correlating distinct spaces within the abbey. Monasteries have therefore long been constructed on similar ground plans. Van der Laan’s designs honour these Romanesque foundations and bring to bear on them the experience of modernism. As a result, the building feels extremely ancient and yet somehow encompasses the experience of Europe’s catastrophic twentieth century.

The distinctness of spaces is emphasised by the way in which they are used at different times of day: the chapel for the eight services, the crypt for private prayer, the cloister for evening recreation. Again, the exact rhythm of the abbey follows closely from The Rule, in which St. Benedict fearsomely describes the punishments that should be meted out to any brother who is late for a service or a meal. Life in the abbey is like living in a human clock; the rituals of singing, eating and sleeping mark out the passing of time. These rituals are repeated day after day, week after week, as the monks sing their way through all 150 Psalms every seven days. Part of the function of the community is to mark out God’s time, to mark out the years through which each of the brothers live. The sense of the passing of days is emphasised by the movement of light around the chapel, the bells that are rung at Laudes and at Vespers, and the graveyard just beyond the cloister.

Patrick Leigh Fermor, following his first visit to an abbey, wrote in 1957: “Only by living for a while in a monastery can one quite grasp the staggering difference from the ordinary life that we lead. The two ways of life do not share a single attribute, and the thoughts, ambitions, sounds, light, time and mood that surround the inhabitants of a cloister are not only unlike anything to which one is accustomed, but in some curious way seem its exact reverse.” -

James Marriott is an artist, activist and naturalist and works as part of Platform. This collective, based in London but working with allies internationally, combines artists, educators, activists and researchers who work to assist social and ecological justice. Founded in 1983, Platform has had a particular focus since the mid-1990s on global oil and gas corporations, campaigning against its impacts on the climate, as well as human rights, the environment and democracy. Marriott’s most recent book, co-authored with Mika Minio-Paluello, is The Oil Road: Journeys from the Caspian to the City of London (Verso 2012).

A longer version of this article first appeared on Platform on Oct 22, 2014 under the title: A journey to ‘communities of the ideal’.

It is a truism to say, as many of us do, that there are not enough hours in the day to complete the tasks that one’s everyday work demands. Of course a sense of being busy is common to all walks of life – even the abbot at Sint Benedictusberg told me that the previous months had been hectic. But whereas life in the abbey on one day, one week, or one year will be more or less as it is the next day, next week, or next year, my life in the city seems to become increasingly hectic. The future is always expanding, and with it the workload. Meanwhile, the definition of what is “work time” and what is “non-work time” is constantly being altered by technology, and workers are required to be “flexible”, or rather available for work well beyond working hours.

The problem is the distinctness of Time, for those of us not living in monasteries, is being eroded.![]()

![]()

-

![]()

Eco Beach

Lima, Peru

-

If you fancy going all eco on your next holiday, green-washing your conscience of environmental guilt, Eco Truly Park might be the place. Located on the west-coast of Peru, this ecovillage accommodates visitors from all over the world, offering practical as well as theoretical classes in organic farming.

The park was founded on a sandy, coastal site, that has been transformed into a self-sufficient farm fuelled by over twenty years of collaborative work by the permanent residents and volunteers. Its success lends some credence to the community’s claims that their ecological approach could provide an alternative model for solving the extreme rural poverty suffered by many of Peru’s population. Unlike other ecovillages, the community has come up with a rather whimsical way of building its houses. Inspired by Indian spiritual ideals, the park consists of about 30 cone-shaped buildings called “Trulys”. While the name’s etymology is unclear, the special form of each building is supposedly thought to preserve energy in its centre, but in less spiritual terms, the tall vented volumes provide effective natural air conditioning, keeping the shelters pleasantly cool at night. Decorated with Indian-inspired motifs, the dwellings are made from local materials including mud, stone, reclaimed wood and even glass bottles. p (sf)![]()

![]()

Photos: previous page and building details, courtesy Santiago Stucchi Portocarrero; beach view, courtesy Eco Truly Park.

-

Enduring

ConsensusFreetown Christiania at forty-three

By Malcolm Miles

![]()

-

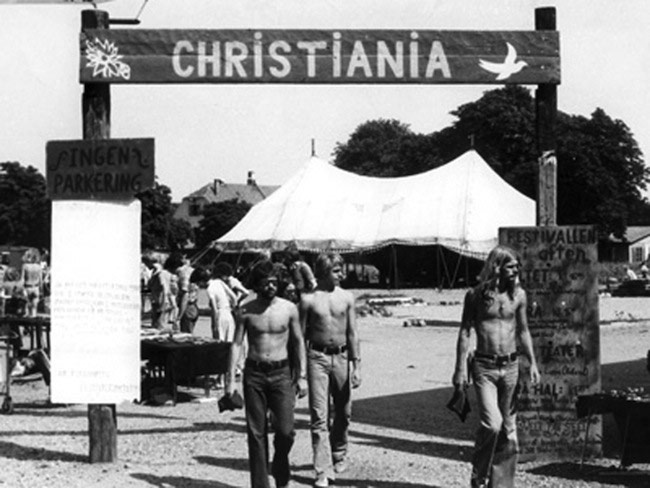

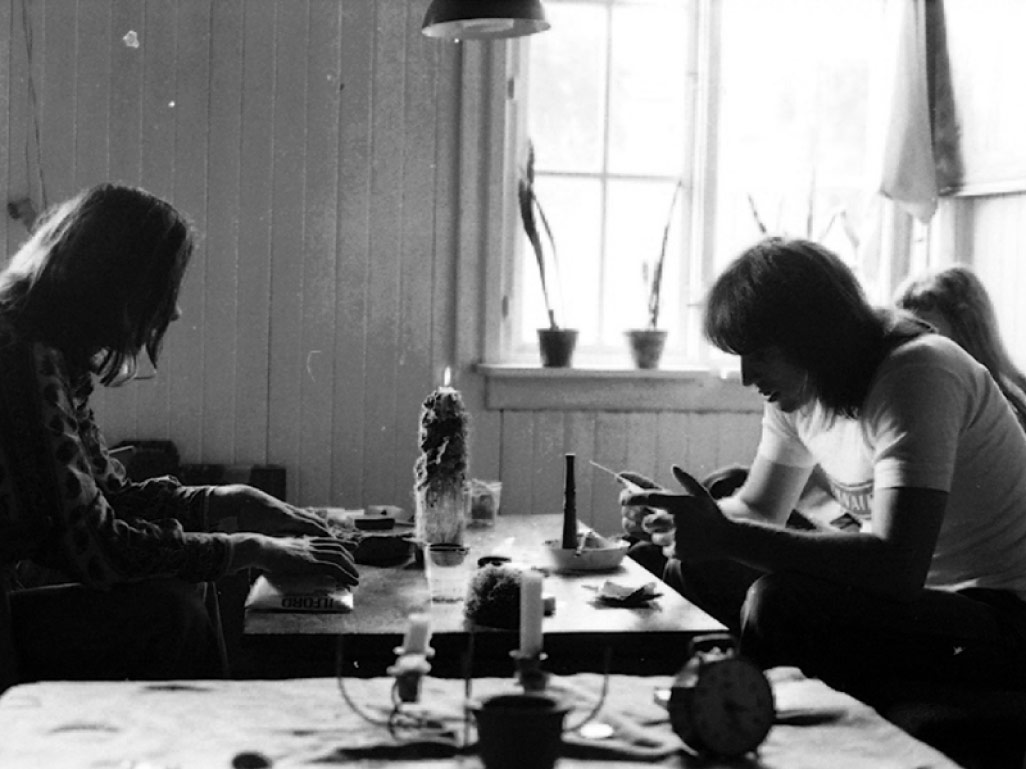

So many communes of the 1960s and 70s were children of their time and very few endured beyond a decade. But Denmark’s famous Freetown Christiania turns 43 this year. Cultural theorist Malcolm Miles believes the longevity of this robust community owes as much to its protracted system of self-government as it does to eco-friendly attitudes and the relatively tolerant reputation of its host country.

![]()

In 1967, the Danish military moved out of a 34-hectare site that had served as a barracks in a central enclave of Copenhagen since the seventeenth century. The area fell into a dilapidated state until, in September 1971, it was declared “free” by members of local squatter movements, with Freetown Christiania founded the following year.

Today, tourist websites promote the opportunity to visit Christiania “like an insider”, with reviews ranging from “So cool! What a way to live!” to “This is one of those places you either love or hate… I hated it”. The community is one of Copenhagen’s biggest tourist attractions. It is car-free (although some residents have shared cars parked nearby), has several cafés and shops, and contains footpaths through woodlands and reed beds offering a quiet escape from the city. Although a right-wing government tried to reassert control over the site in 2004, aiming to redevelop it for condominiums – it is the kind of waterfront site from which developers make fortunes – Freetown has survived. It is still a commune, and one of Europe’s largest alternative settlements with a sustainable community of 850 people, despite failing to resist the government’s extension of its authority over the site in a series of court actions up to 2011.

Obviously there is more to Freetown’s survival than merely tourism; images of police clearing women and children from self-built houses in an idyllic setting once and for all would have done no favours to Denmark’s liberal image and the city’s lucrative cultural tourism trade. But that only explains why it has not been cleared, not why it remains a viable community, an alternative society within the territory of the old regime.![]()

-

![]()

This is down to two other factors: Freetown’s social (rather than built) architectures, and its fusion of 1970s free living with today’s concern for more sustainable, greener forms of dwelling.

Like many intentional communities and eco-villages founded since the 1970s, Christiania employs consensus decision-making, not majority-voting (which is regarded as divisive and impositional). The process can be slow, but it generally creates social coherence by enabling everyone, on a basis of equality, to voice their feelings about everyone else. What is being discussed is less important than the act of discussion as a safety valve of vocal expression in proximity to others.

Whilst Freetown Christiania is seen by the Copenhagen city authorities as a single entity, it is actually a collective of many groups and individuals who have their own ideas as to its vision and purpose. For some members, retaining free use of soft drugs is a key, almost ideological issue; for others, negotiations over Christiania’s relations with the city are more like a planning process to be approached pragmatically. Therefore, despite three decades of more or less acceptable co-existence, when faced with threats from both city and state authorities to normalise governance and economic basis in the 2000s, the community’s internal meetings were large and at times fraught.

According to the government’s victory in the Supreme Court in 2011, Freetown was invited either to transform itself into a less alternative community, or to buy the site it occupies. The community’s first response was to close Freetown to visitors, thereby diminishing Copenhagen’s critical mass of attractions. This was, in effect, to go on strike. Behind the barriers, meetings moved slowly and at times painfully towards a plan, which involved the eventual purchase of the site for 125 million kroner (16.8 million euros), with significant deductions for renovation of services and repairs to listed buildings.

The principle of consensus has at times been a messy process, but has still proven to be vital research-and-development work for a new society evolving and enacting its own set of values. This is necessarily contingent on external conditions, and residents of Christiania pay rent and collectively contribute to the cost of services provided within the city’s infrastructure. In one way this is a normalisation; in another way, however, it is a negotiation to preserve what matters most: autonomy within the boundaries Freetown.

![]()

-

![]()

The residents of Copenhagen’s famous enclave have endured various threats to its sovereignty during the past four decades, but through the principle of consensus, they have worked to secure its future. (All photos courtesy christiania.org with the exception of resident meeting image, Nils Vest)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

-

Malcolm Miles is Professor of Cultural Theory in the Architecture School at the University of Plymouth. He is author of Urban Utopias: The built and social architectures of alternative settlements (2008); Herbert Marcuse: An aesthetics of liberation (2011) and Eco-aesthetics: Art, literature and architecture in a period of climate change (2014). His next book is Limits to Culture (2015), a critical retrospect on the cultural turn in urbanism since the 1980s.

malcolmmiles.org.uk

![]()

![]()

![]()

Recently, a series of workshops, conducted according to the rule of consensus, produced a new plan for Christiania; with it, the town’s existence has now been officially recognised by the city. The new plan has a greater emphasis on ecology, which has always been part of the Freetown ideology. But while a few radical thinkers in the 1970s, such as Rudolf Bahro and Herbert Marcuse, saw environmental destruction as the flip-side of military destruction during the Vietnam War, it is only now, with the effects of climate change being felt, that the links between military, industrial and security interests under neoliberalism have gained prominence.

Whereas much discussion about sustainable cities remains technical – designing green skyscrapers or devising new energy reductions – it tends to ignore the social sustainability aspect, which is an equally vital consideration for a greener future. Christiania is now looking to increase food production on site, extend its car-share scheme, recycle waste from the whole of Denmark, and continue to operate through consensus decision-making. There will be more long and difficult meetings, no doubt. Yet that is how a radically new society replaces the hierarchies and hegemonies of the dominant society through equality and direct democracy. The social architecture of consensus is not an add-on, but is what has enabled Freetown to remain free. I

![]()

-

![]()

Connected Communards

Mount Telaithrion, Euboea, Greece

(Photo: Michael Pappas)

-

In 2008 four twentysomething friends in Athens started discussing setting-up a self-sustaining eco-community as a model for a better way of living together. By 2010, fed up by the rising economic crisis, they packed in their jobs as web designers and programmers and moved to the Greek island of Euboea, about three hours from Athens. There, they constructed yurts (because these don’t need costly building permits) and compost toilets, and planted vegetables and medicinal herbs. They named their commune after the mountain where it’s sited: the “Telaithrion Project”.

From its vantage point overlooking the Aegean Sea, the new commune’s choice of site seems almost mythical, but it was chosen primarily because one of the founders’ families originates from the nearby village of Aghios. So while the young “communards” (a few indeed long-haired and guitar-playing) are still viewed suspiciously by some locals, others have lent them tools and provided advice, as none had any experience as farmers.![]()

![]()

Photos: Tania Stergiannakou, courtesy FreeandReal

-

Five years on the community has grown to more than 20 residents. A geodesic dome serves as a central congregation (and yoga) space, a forest has been planted and a lake begun to be dug to increase the diversity of nature, and they now grow 80 percent of their food, bartering for the rest.

So far so communal, but the interesting aspect is how the communards combine self-sufficiency with connectivity. Telaithrion is globally connected via its website and Facebook, which enables them to crowd fundraise for further resources and create a worldwide network of supporters. Around 12,000 of these have visited, contributing labour and knowledge to the community, with the idea that they go away inspired to found their own.

![]() (fh)

(fh)Photo: Eleni Frantzi

-

In the Photo Booth with ...

Piet Hein Eekuncube bumped into Dutch designer Piet Hein Eek at Spazio Rossana Orlandi during the Salone del Mobile in Milan. An impromptu, on-the-spot photo booth session ensued, where he told us about his workspace architecture, and his thoughts on individuality and communality, aesthetic freedom and predicting the future.

Interview by Sophie LovellPhotographs by Orlando Lovell

![]()

-

You have a successful business making your own furniture, so why architecture now as well?

When we moved studio in Eindhoven in 2010, we developed the building ourselves. It’s much more than just a workplace: with a restaurant, studios, event space, shop and an art gallery – and it’s big, with around 80 staff. This inspired others to ask me to suggest ideas for developing other old industrial buildings.

How big is the architecture studio in your company ?

Just one architect and me at the moment. We didn’t expect many architecture projects, but now have more than we can handle. One is the concept, communication and redevelopment of a beautiful 1950s building in Rotterdam – 22,000 square metre of mixed-use residential. So we’re quite busy.

You’ve a new idea to provide a basic grid frame building for occupants to slot modules of their own design into. Don’t you miss out on the creative bit?

My thinking is to create a steel structure, which gives occupants freedom to create their own worlds. So for this I’m more like an engineer than a designer or architect. For me it’s the opposite of freedom.

-

So you want to create a rigid structure within which the occupants can be free?

Yes – so it is clear for everybody what their options are. Normally really individualistic things can’t be piled up or put together. With this structure you create boundaries, both technical and aesthetic, that people have to work within.

Do you imagine a different kind of workplace community evolving out of this structure?There will be a range of different businesses – from the very small to the big. But this process is not about determining how it’s going to be, or who is going to be in it, which is the normal way buildings are developed. Architects and developers want to know what’s going to happen: to predict the future, make a plan and then execute it. But the future is not predictable, it’s a stupid way of working. It’s much more logical to create a structure and open up an organic process.

With a mentality built on safety and security, when projects become bigger and more complicated, more energy is put in to make them more predictable. But that’s looking for false certainty and is the opposite to what you should do.

You need to find a process that incorporates insecurity, acknowledging that people are individuals and want different things, and taking this as a starting point. Then you’re only making what is necessary and demanded. -

Piet Hein Eek (*1967) graduated from the Academy for Industrial Design in Eindhoven, The Netherlands in 1990. His diploma project was a set of cupboards made from scrap wood, which he sold and used the money to found his own design studio. He now operates his own design and production firm building his designs, made primarily from recycled materials on site in his own workshops. He also has a shop and restaurant on his factory site as well as studios. His work is sold in numerous galleries worldwide.

Do you think there’s space for communal attitudes within working environments?

Yes, but the main issue isn’t that of communality. Like when a good government takes care of stability, freedom and food, people are able to grow, get educated, become entrepreneurs, because their basic needs are covered. They dare to do things because they’re secure, in a safe environment.

So freedom, in your view, comes from creating boundaries, rather than removing them?Freedom comes from the opposite of what one normally associates with the commune idea: in the way an environment is managed. I think the only things one should arrange is the hardware needed for people to develop themselves: not creating their world for them, but enabling them to create it themselves.

But most architects and developers and politicians try to arrange too much: they don’t try to create space, they try to fill it in. -

![]()

-

Photo: Kate Peters

Bricks

Issue No. 35:July 2nd 2015

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»I don’t mistrust reality of which I hardly know anything. I just mistrust the picture of it that our senses deliver.«

Gerhard Richter

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents