-

Magazine No. 35

Bricks

-

No. 35 - Bricks

-

page 02

Cover

Bricks

-

page 03

Editorial

Bricks

-

page 05 - 12

A Brick in the Stomach

Max Borka on the home-loving Belgians

-

page 14 - 15

Trümmerfrauen

The women who cleared the debris of Berlin

-

page 16 - 19

H Architectes, Barcelona, Spain

Architects on building in brick 1/4

-

page 20 - 21

Walls of Faith

Arthur Shoosmith’s New Delhi church

-

page 22 - 26

Baumschlager Eberle, Lustenau, Austria

Architects building in brick 2/4

-

page 27 - 35

Catching the Curve

Eladio Dieste and the brick by Florencia Rodríguez

-

page 36 - 37

Collective Constructs

Olafur Eliasson’s Collectivity Project

-

page 39 - 40

Wall-E

Gramazio & Kohler’s masonry robots

-

page 41 - 46

Trapped by History

The new genre of stylish salvage

-

page 47 - 48

Breaking Point

On the art of blowing up buildings

-

page 49 - 52

Sergison Bates Architects, London, UK

Architects on building in brick 3/4

-

page 53 - 54

Blood Bricks

Child labour in the kilns of Nepal

-

page 55 - 58

Onion, Bangkok, Thailand

Architects on building in brick 4/4

-

page 59 - 60

Masonry Maximus

A pile of palaces in Ancient Rome

-

page 61 - 64

In the Photo Booth with...

Wolf D. Prix

-

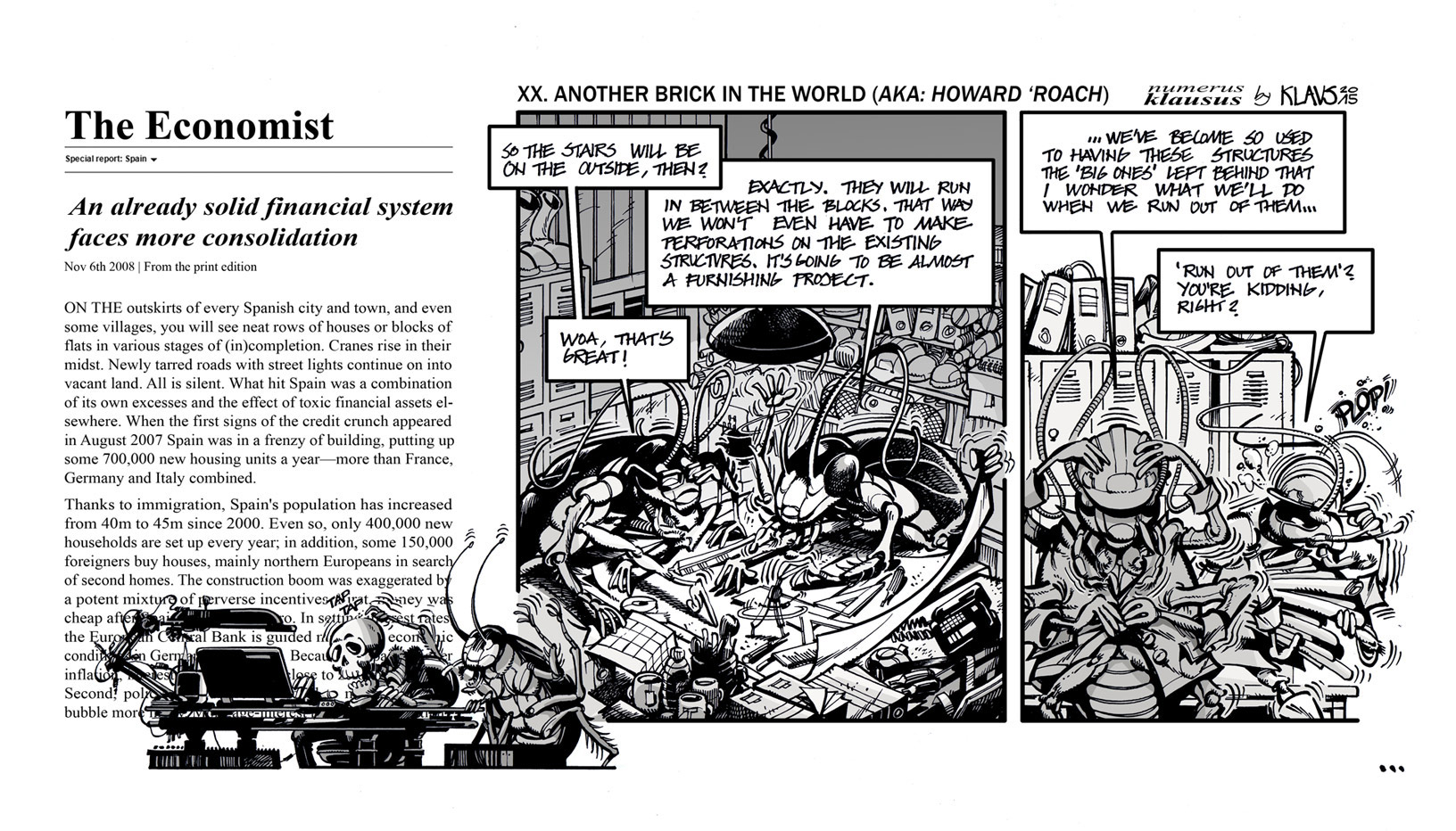

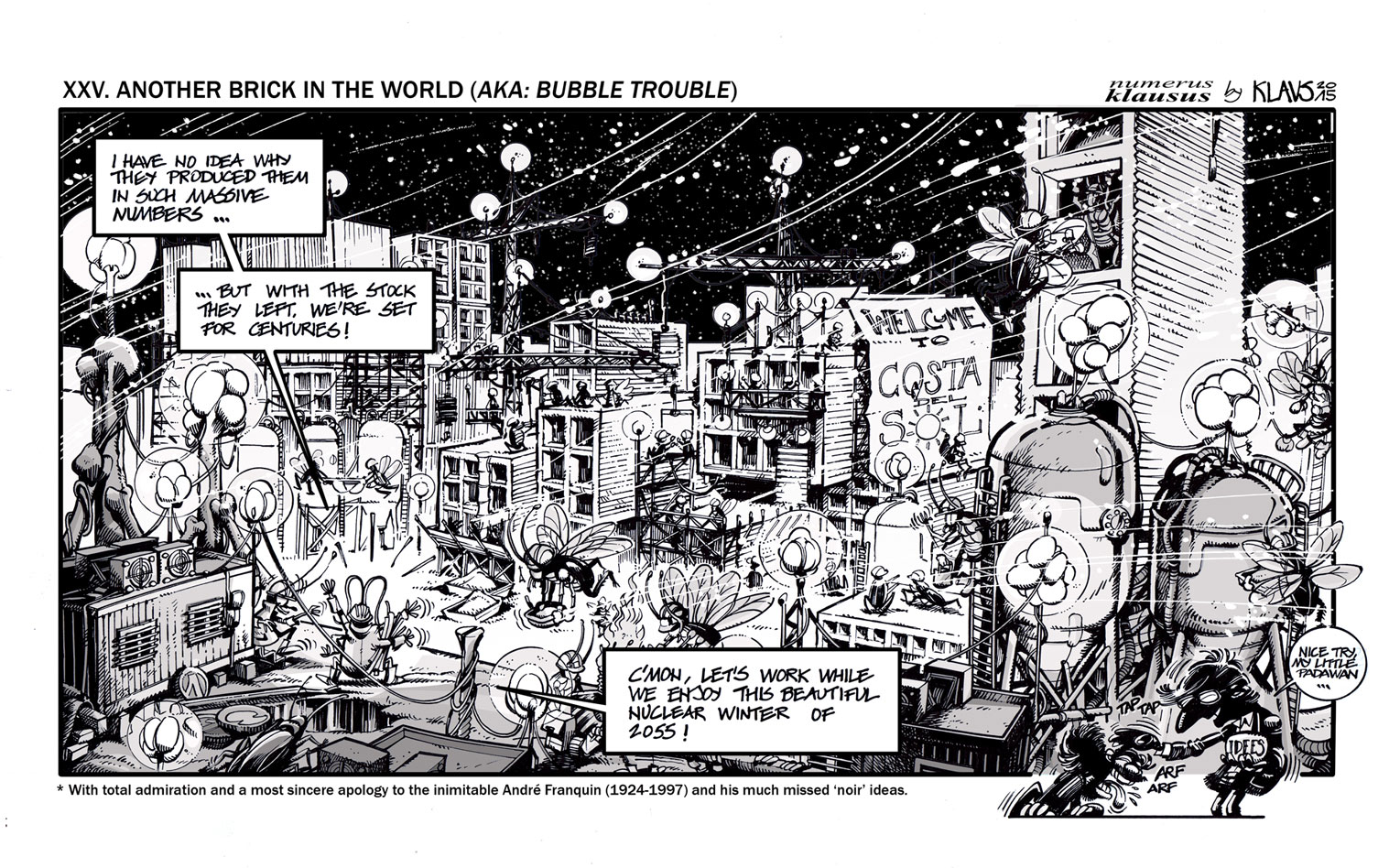

page 65 - 66

Klaustoon

XX. Another Brick in the World

-

page 67

Next

Uncanny Valley

-

-

uncube’s editors are Sophie Lovell (Art Director, Editor-in-Chief), Florian Heilmeyer (fh), Rob Wilson (rgw) and Fiona Shipwright (fs); editorial assistance: Sara Faezypour (sf); graphic design: Lena Giovanazzi; graphic assistance Diana Portela.

uncube is based in Berlin and is published by BauNetz, Germany’s most-read online portal covering architecture in a thoughtful way since 1996.

Warm, welcoming, long-lasting, cool-keeping, versatile, bombastic bricks! uncube’s issue no. 35 is devoted to our favourite modular building material. Share a journey with us from “ugly” brick houses in Belgium to masonry symphonies in Uruguay via soulful examples of historical salvage and contemporary practices exploring the endless potential of these little baked blocks of clay.

And don’t miss our photo booth encounter on page 62 with the towering presence of Wolf D. Prix.

Just follow the yellow brick road…

Cover image: Technical Administration building, Hoechst AG, Frankfurt, Germany, 1924, designed by Peter Behrens. (Photo: Klaus Peter Hoppe, © Infraserv Höchst GmbH & Co. KG)

-

A Brick in the

Stomach

On the home-loving BelgiansBy Max Borka

-

The Belgian curator and critic Max Borka says his countrymen are a staid and stubborn bunch when it comes to their homes, but their relationship with brick is “inbuilt” and surprisingly anarchic.

To be born with a brick in your stomach, een baksteen in de maag, as they say in the Flemish-speaking northern part of the country, or être né une brique dans le ventre, in the Walloon and French-speaking south, essentially means that – as a Belgian – it is in your genes, not just to own, but also to build your own home, and then to keep it.

In Belgium, only about 25 percent of the houses are let to tenants, the rest are lived in by their owners. If you still are a tenant after your student years, you are considered a failure. True Belgians marry young, start a family, buy or build a house as soon as they possibly can and then keep on living in it and paying for it for most of the rest of their lives. A property in Belgium is sold only every 35 years compared to every 10 years in Anglo-Saxon countries.You won’t find any manifestos or great movements of Belgian origin in history books about art, design and architecture. Like our national hero René Magritte, who immediately got into trouble with the surrealist movement the first time he travelled to Paris, we are born individualists. Our favourite pastime is minding our own business and the place we like best to practice this is our home, which we consider to be our castle – and our bunker.

Previous page: “Partners in crime” one of the architectural dog’s dinners with accompanying witty descriptions found on Hannes Coudenys’ blog Ugly Belgian Houses. (Photo: Hannes Coudneys)

-

![]()

“So who was ugly first?” another entry from Hannes Coudenys’ “Ugly Belgian Houses”, this time from the book version. (Photo: Kevin Faingnaert)

-

The Belgians have made a habit of expressing their individuality through their houses. We therefore prefer to construct them from scratch, each one unique and custom-built, rather than buy existing ones, even though, thanks to the fact that our small country is almost full up, this is becoming increasingly difficult. Perhaps the desire to scare off others might explain why we have made a principle of building our houses as ugly as possible.

A trip through Belgium rapidly confirms that the Belgian attitude towards the classical architectural canon is somewhat anarchic. We also prefer to tackle the job of building ourselves, literally, with the help of all hands available, and in a makeshift manner. And since the material is so easy to handle, cheap and versatile, we also prefer to construct using what we already have in our stomachs: bricks.![]()

Admittedly, since Belgian property is built for the long term, the constructive quality of the houses is very high. But it is often also much more eccentric than it is innovative, a pastiche of architectural styles that is not unlike the comic strips in which we also excel. The clash between these harsh varieties of individual “styles”, creates a cacophony that is second to none. Added to this is our obsession for lintbebouwing or ribbon building: endless strips of individual houses that connect the numerous villages and towns to each other, and that have transformed most of the countryside into one giant suburban sprawl.

Not that most of us Belgians have a problem with that. When in 1968 one of the leading Belgian avant-garde architects Renaat Braem wrote a book about his home country, he scornfully named it The Ugliest Country in the World – a title that was quickly turned into an epithet that Belgians have been quoting with great pride ever since.

![]()

Above: “It’s a tribute to their letterbox” ; below: “Lemmy was here”; “When you didn’t know you had to bring your own roof”; “Shiteau. The Belgian version of a château” –– more entries from “Ugly Belgian Houses”. (Photos: Hannes Coudenys)

-

»Our favourite pastime is minding our own business and the place we like best to practice this is our home, which we consider to be our castle – and our bunker.«

Despite the economic crisis and the fact that there is hardly a morsel of land left, young Belgians don’t think much differently from their parents when it comes to building their own house for life. Alternative housing types such as co-housing, kangaroo- or multigenerational living still remain exceptions. Nor do such models get much support from local politicians, who know all too well that it would simply be political suicide to aggravate their voters’ basic distrust of all state intervention. Owners in Belgium therefore enjoy some very interesting tax benefits compared to other countries: rental income from properties, for instance, is not part of the owners’ income and therefore not taxed as such.

This may leave the reader wondering whether we have any architects at all in Belgium. We do! And how! Their number, 7,714 according to the latest count, is even extremely high per capita compared with neighbouring countries – partly due to the fact that (and this may come as a surprise) you are obliged to hire one when you build in Belgium. The number of public commissions reflects the power of the government in Belgium, however. That is: they are almost nonexistent. So if you want to make it as an architect, you have to concentrate on the private sector.

Belgian architects like Henry Van de Velde were prominent members of the very first international design movement, Art Nouveau, where the house stood central and its comfort equalled the Baudelarian luxe, calme et volupté. But that quickly changed when Modernism exalted other, less bourgeois, values. Paul Hoste, for example, was publicly scorned by Theo Van Doesburg, the theorist behind de Stijl for his “ambiguity”, read: making client comfort a central theme. Little has changed since. -

»We also prefer to construct using what we already have in our stomachs: bricks.«

![]()

![]()

Left: “Please stop using these spirals. Not cool. Never cool. Aaaargh.”; centre: “Lord of the Bling Blings”; right: “Dude, your house is melting”: a final installment of architectural crimes against humanity from“Ugly Belgian Houses”. (Photos: Hannes Coudenys)

![]()

-

![]()

Rabbit Hole, Lens°ass Architects, Gaasbeek, Belgium, 2010. (Photo: Philippe van Gelooven, courtesy Lens°ass Architects)

-

Max Borka was born in Belgium and now lives in Berlin. After a career as a journalist and media-manager, he became director of the Interieur Foundation in Kortrijk, and art director of designbrussels. He also wrote and curated numerous books and exhibitions on art, architecture, fashion and design. He was a co-founder of Damn° magazine, and recently launched Mapping the Design World, a platform on social design and the Stand der Dinge / State of Design – Berlin festival. He also currently teaches Design Theory at the Fachhochschule Potsdam.

![]()

Many Belgian architects today limit their creative input almost exclusively to signing off a design, after streamlining the clients own plans a bit. But on the other hand, there’s always been a great line of architects, like Jacques Dupuis, whose oeuvre was almost exclusively limited to villas and bungalows, and whose works were ignored by the chroniclers of Modernism.

All that might change though, now that attention has shifted towards the vernacular with DIY and Maker cultures comfortably installing themselves at the core of a new canon at the service of the client. Of late, and in the wake of pioneers such as Luc Deleu, bOb Van Reeth, & Robbrecht & Daem, a third category has emerged, armed with an aesthetic that fully celebrates Belgitude, often taking its culture of non-aesthetics to extremes.

![]()

DnA House, BLAF Architects, Asse, Belgium, 2013. (Photo © Stijn Bollaert);

Villa H. te W., Stéphane Beel Architects, Belgium, 2011. (Photos: Luca Beel)

Not surprisingly, the brick – cheap, versatile, modular, anonymous and commonplace – plays a central role in the design work of these small and flexible studios. Already famous examples are Villa Moerkensheide by Dieter De Vos in de Pinte; the Brick Rabbit hole, a house plus vet practice by LENS° ASS near Gaasbeek Castle; and the DnA house on a left-over plot in the town centre of Asse by BLAF Architecten. “Blaf” is Flemish for “bark”, which betrays another common characteristic of these projects: a sense of humour, which also pervades the blog Ugly Belgian Houses. Launched by Hannes Coudenys four years ago, with photographs of houses across Belgium, the site attracts millions of visitors per year, from all over the world. This of course makes us Belgians all the more happy.

![]()

-

![]()

![]()

-

It began as a spontaneous response to the scenes of annihilation when citizens emerged from cellars and bunkers in cities across Germany in May 1945. In the face of national defeat, by picking up one brick, then another, these women (for it was largely only women left in the cities) took the first steps towards starting over. Amidst the chaos of destruction, which had turned much of Germany’s hitherto neatly mortared brickwork into 400 million cubic metres of debris, they began the work of reconstruction.

It was later, as their efforts became coordinated under an official Allied order compelling all able-bodied women aged between 15–50 to assist, that these women became known as Trümmerfrauen: “rubble ladies”. Working in gangs with hardly any tools, they would clear wreckage brick by brick, passing each one along a line, to be cleaned and stacked neatly, ready for reuse. Thanks to this recycling process, roads re-emerged, dwelling spaces were reclaimed and eventually the cities themselves began to take shape once again. Something else also materialised from this hard manual labour: the humble attitude with which these women got on with their toils contributed towards another process of repair – that of the country’s psyche. I (fs)

Photo © SLUB Dresden/Deutsche Fotothek/Roger & Renate Rössing

-

Building in Brick 1/4

H Arquitectes

Barcelona, Spain

The young Spanish practice H Arquitectes likes to build in brick – but their houses are anything but domestic. Partner Xavier Ros Majó explains their passion for clay.

-

Three of the single-family-houses your office has designed

make heavy use of brick. Is this a favourite material of yours?»Well, we love many other materials too, but you are right, we love to work with brick. For these three houses, we were looking for a material that could serve both as structure and surface, so we would not need any additional layers. We are constantly preoccupied with a spatial concept we call “espacio estructura”, meaning that all the spaces in our buildings are defined by the load-bearing structure itself.

«

Casa 712 in Barcelona was completed in 2011. Based on a triangular floor plan, the house features a façade of two layers of bricks, with the structural wall inside (in order to avoid thermal bridges) while the bricks of the exterior wall were turned on their sides with their holes facing outside; this way the façade is ventilated and there is a cavity that easily drains the water thanks to the bricks’ geometry. (All photos by: Adrià Goula)

-

Casa 1014 in Granollers, Barcelona, was completed in 2014. The plot is 53 metres long yet only 6.5 metres wide. Making use of the entire length, H arquitectes split the house into two parts, placing them at each end of the plot thus creating a very long patio in the middle. The structural bricks were left visible, their different sizes and structure giving a hint of their varying functions as aesthetic, load-bearing and/or thermal elements.

-

H Arquitectes is an architecture studio established in 2000 and based in Sabadell, Barcelona. The studio is managed by four partner architects: David Lorente Ibáñez (Granollers, *1972), Josep Ricart Ulldemolins (Cerdanyola del Vallès, *1973), Xavier Ros Majó (Sabadell, *1972) and Roger Tudó Galí (Terrassa, *1973). All of them licensed between 1998 and 2000 in the E.T.S.A. Vallès. They have lectured across Europe and America and their works have been recognised with several awards and have also been featured in several exhibitions.

www.harquitectes.com

Despite its universality as a material, do you see brick

as a particularly indigenous material in Spain?»Brick is an essential part of our vernacular and traditional construction. I think this could be said for the entire Mediterranean culture. Despite the savage economic crisis, there are still a lot of brick factories in Catalonia and almost all building companies know how to work with masonry techniques. So, in this way, brick is one of the most traditional and deeply rooted construction technologies here.« I

-

![]()

![]()

-

The severe, blank bulk of St Martin’s Garrison Church formed of three and a half million bricks, has an elemental ageless air, resembling something like the bastard child of the Ziggurat of Ur and a power station. The thick walls and minimal openings of its massive abstract form serve a practical purpose, keeping the lofty basilica-like interior coolly isolated from the often blazing heat outside.

Built between 1929–31, St Martin’s was designed by Arthur Gordon Shoosmith (1888–1974) as the parish church for the military cantonment of New Delhi, the newly minted capital of British India. Shoosmith was assistant to one of its planners, Sir Edwin Lutyens, who had advised him: “get rid of all mimicky Mary-Anne notions of brick work and go for the Roman wall”. Shoosmith followed his advice – and then some – producing a building that in its stolid, fortlike presence seems at first sight to express the uncompromising solidity of British imperialist power.

However after the decorative excesses of earlier imperial pomp-fest buildings, which had superficially riffed off the intricate detailing of Hindu and Mughal monuments and temples, its sober severity exudes more an air of introverted defensiveness appropriate to a time when questions over British rule in India were growing louder, resulting in Indian independence less than two decades later in 1947. I (rgw)Image © RIBA Library Drawings Collection

-

Building in Brick 2/4

be baumschlager eberle

Lustenau, Austria

Baumschlager Eberle architects are not so much interested in brick as in sustainable and endurable architecture. Their mixed-use building “2226”, has extremely thick brick walls making technological devices for climate control, heating and cooling almost entirely obsolete. Founding partner Dietmar Eberle explains to uncube why taking brick back to its low-tech qualities actually leads to one of the most advanced uses today for this historic material.

-

How does your 2226 building work?

»Most contemporary buildings use less energy, but require more technology. Our building 2226, in contrast, works with people, utilising their warmth, humidity and energy. What we need for this is technology to steer the air and energy flows – and massive components, such as the thick brick walls, to serve as thermal mass. This building is an experiment to see how far we can go using only the heat from the occupants and their appliances to heat the building. A year and a half after we started using the building, we have found that the temperature fluctuation throughout the entire year is only five degrees Celsius.«

Building 2226, Lustenau, Austria, 2013. (All photos courtesy Baumschlager Eberle)

-

Basically the building is just a very simple load-bearing structure

with reinforced concrete floors supported by brick walls isn’t it?»Correct: the solid exterior walls are 76 centimetres thick and comprise two interlocked brick walls, each 38 centimetres thick and with varying density. This enabled us to balance out the varying insulation, thermal and structural qualities. Bricks were by far the best building material for this purpose, since they are simultaneously capable of bearing load and heat flow insulation as well as storing heat and moisture.«

-

![]()

Even though brick is the most important material in this project, the architects decided to plaster over and not express it. “Other than brick, lime plaster is a very common sight in this region of the Alps”, says Eberle, “and it supports and complements the climatic characteristics of the brick: it absorbs and stores humidity. The light colour also reflects the daylight, helping to significantly reduce the use of artifical light inside, especially important given the very deep reveals of the thick brick walls.”

![]()

-

Dietmar Eberle (*1952) studied at Vienna University of Technology in Austria. He was co-founder of the Baukünstler design movement in Vorarlberg, Austria, in 1979. From 1985-2010 he ran a joint practice with Carlo Baumschlager. He has held various teaching posts in Hannover, Vienna, Linz, Zurich, New York and Darmstadt since 1983 and is Professor of Architecture at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, Switzerland and head of its Centre for Cultural Studies in Architecture. He was Dean of the Faculty of Architecture there from 2003 to 2005.

baumschlager-eberle.com

With all these “smart houses” around would you define 2226 as “low-tech”?

»I don‘t think this building can be categorised in that way at all. The building materials are low-tech, but the control system technology is the absolute latest. You could say though, that 2226 eludes any machine-romanticism, because its technology is almost invisible and pragmatically implemented. It is all about sensible cooperation between material and technology: to make use of the structural intelligence of the material – and push back the mechanics.

« I

Detail sections of the attica and a facade section, revealing the thickness of the brick walls. (All drawings © Baumschlager Eberle Architects)

-

Catching

the CurveEladio Dieste, the brick and a certain ethos

By Florencia Rodríguez

-

The architect, critic and founder of PLOT, Florencia Rodríguez sings the praises of the “symphonic” works of the Uruguayan architect and engineer Eladio Dieste and of his love affair with brick.

In analysing modern architecture in Latin-America one rapidly comes to realise that it’s not possible to think about the continent as an unbroken whole. There are of course some shared colonial histories and traditions between countries, but the way in which these interacted with local vernaculars or particular idiosyncrasies resulted in many different ways of thinking about and approaching the built environment. It might be more accurate to think about South America as the sum of different regions, each defined by its geographical features like the Andes, the Amazon or the Río de la Plata.

In the case of what we call the Cono Sur or Southern Cone of the continent, the Río de la Plata (the River Plate) has played an important part in the constituting of a certain way of being modern. This estuary or gulf, dividing Argentina from Uruguay, has on its opposite shores those two countries’ capital cities, respectively Buenos Aires and Montevideo, which thus share opposing but equally phantasmagoric views of the other side, giving each a constant feeling of otherness.

During the first decades of the twentieth century, immersed in the construction of their political identities and institutions, these two countries gave rise to strong eclectic tendencies, stylistic revivals and beaux arts academicism leading on to a very French take on early modernism, with Le Corbusier in the role of pioneering hero above all.Previous page: Cristo Obrero Church façade, Atlántida, Uruguay, 1958-60. (Photo: Samuel Smith)

-

Uruguay and Argentina weren’t defined then by the epic public and monumental modern architecture that was seen in the growth of other Latin American countries like Brazil or Mexico. What was particular about them took place on the domestic, residential scale, changing completely the look of their cities and the lifestyles of their people. Montevideo’s waterfront and skyline, for instance, is still defined by the most subtly modernist, homogeneous, ascetic and white architecture imaginable, extending for block after block into the distance.

Confronting this formal field condition, which some felt artificially imposed upon local conditions, various voices started to urge for a more equitable and responsive relationship between society and its built environment. -

One of the most interesting representatives of this philosophy was Eladio Dieste, the Uruguayan engineer and architect, born in 1917, who claimed to have “discovered in brick a material with unlimited possibilities”, and, feeling it had been almost completely ignored by modern technology, began to study and use it structurally. He rationally maintained that a universally modernist form of architecture would not be appropriate for this southern region of the world due to “lack of suitability, modesty and seriousness when facing the architectural and constructional problems that are specific to our very different environment”.

He considered architecture to be an art form subject to morality: one that should both drive and provide the impulse for fulfilling mankind’s potential. He was an idealist, an expressionist and a romantic who chose this little, repetitive ceramic object as the tool to push the limits of form-making and perception of space. In the process, he completely annulled the reductive distinction between high tech and low tech.

Dieste thought that the use of brick caused a shift in the predominance of prismatic shapes, with their flat surfaces and edges, towards more complex surfaces as diaphragms, vaults, angled structures or polyhedral domes. He asserted: “This new technological path has obvious formal and therefore architectural consequences. With the use of brick, the elaboration and construction of space, which is the goal of architecture, is defined and limited using forms, colours and textures. The fact that this technology leads to the predominance of varied surfaces tends to produce more magnificent – one could say symphonic – spaces”. It is in this contrast to the auto-referential, element-based or syntactic thinking of much modernist architecture, that the significance of the specificity of each of his projects resides.![]() Details and views of a selection of Dieste’s projects including Cristo Obrero Church, the gymnasium in Durazno and the Montevideo Shopping Centre. (Photos: Samuel Smith)

Details and views of a selection of Dieste’s projects including Cristo Obrero Church, the gymnasium in Durazno and the Montevideo Shopping Centre. (Photos: Samuel Smith) -

CEASA Produce Market, Porto Alegre, Brazil, 1969-72.

(Photo: João Alberto Fonseca da Silva, courtesy Acervo João Alberto) -

Underlining a very sensitive commitment to his work, Dieste thought that if architecture arrived at being an art form and thus achieved happiness, it would make intelligible the indecipherable mystery of the world. His ideas of symphonic spaces and a contemplative communion make us think of a type of baroquism in which the intentions of an extreme (and magical) coherence between all strata of architecture, between materiality, technology, lighting, geometry and perception, coexist.

He experimented with different typologies: churches, houses, bridges, isolated cultural structures and industrial buildings, together forming a vast corpus of work. Significant projects of his include the Christ the Worker’s Church in Atlántida, St. Peter’s Church in Durazno, the bus station in Salto and the CEASA market in Porto Alegre. He built mainly in Uruguay and Brazil but his influence spread through the region as a whole and is still felt today. There are amazing examples of this in contemporary Paraguayan architecture for instance, and in many Argentinian young architects such as Francisco Cadau, Becker-Ferrari, Diego Arraigada and BaBO. His son Eduardo is an engineer as well, who provides a continuity of the family tradition and cooperating with many of these architects.![]()

![]()

CEASA, Porto Alegre, Brazil (Photos: João Alberto Fonseca da Silva, courtesy Acervo João Alberto)

-

»Dieste considered architecture to be an art form subject to morality: one that should both drive and provide the impulse for fulfilling mankind’s potential.«

Silo Torrevieja, Montevideo,Uruguay, 1993. (Photo: Alberto Marcovecchio, Audiovisual Media Service, Farq. UdelaR. 2006)

-

Montevideo Shopping Centre, Uruguay, 1985. (Photo: unknown author. Source)

-

Florencia Rodríguez, architect, critic as well as founder and editorial director of PLOT (2010), the Buenos Aires-based magazine on critical thinking about contemporary architecture. In 2013–14, as part of her academic training, she did the Leob Fellowship in Harvard GSD in Cultural Studies and Critical Theory and Analysis.

PLOT

It is interesting to acknowledge that Eladio Dieste’s work is so complex that it has always been hard to categorise. Many critics name him as one of the most individual of the pioneering modernists, others see in him the expression of the vernacular and yet others find traces of the baroque – as suggested earlier. These multiple readings of his work indicate its significance, in that it cannot be reduced or synthetised into a style, or be seen as merely a simple reflection of a trend or zeitgeist.

His was a search for an essential unity translated into a magnificent constructive pragmatism, rich in political and social ethics, but transformed simultaneously also by a simple belief in the power of beauty and happiness.![]()

Metro Maintenance Hanger, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1971-79. (Photo: Vicente del Amo)

-

![]()

![]()

-

Back in 2005, the Danish artist Olafur Eliasson began an ongoing interactive art project that encourages participants to take part in spatial dialogue, developing their ideas through a space-based process as “an important aspect of defining identity”.

The work, called the Collectivity Project, basically involves a big table full of white Lego® bricks, inviting visitors to create and build a fictional landscape communally. It was first exhibited in Tirana, Albania and after stops at Oslo and Copenhagen, is currently on show as part of the Panorama group show at the High Line in Manhattan, New York until 30 September 2015. For the High Line installment of the project involving some 1,800 kilogrammes of Lego bricks, Eliasson also invited ten big-name architecture practices to contribute Lego buildings to the collective effort. James Corner Field Operations, BIG, David M Schwarz Architects, Diller Scofidio + Renfro, OMA New York, Renzo Piano Building Workshop, Robert A.M. Stern Architects, Selldorf Architects, SHoP and Steven Holl Architects all supplied contributions, which visitors can now adapt and modify to their hearts content over a four month period.

This project comes at a pertinent moment when citizen empowerment is in flux and the right to participate in civic and democratic decisions is very much under scrutiny. “Building a stable society is only possible with the involvement and co-operation of each individual”, says Eliasson, “…your participation matters and has consequences…” I (sl)

Photo: Timothy Schenck, courtesy of Friends of the High Line

-

The world just got littler...

The world just got littler...

To hold one in your hand is to hold a tiny power pack, but its energy comes from the greatest source of energy we know. The sun charges it and it charges your life at the same time.

Maybe you’re a Zimbabwean child that needs a light to study by at night. Or you might be headed to the Roskilde Festival and you need a light for your tent. Maybe you’re going hiking with your friends and you want something better than a battery-powered torch. Or you work in a Himalayan village and you need a hand-held light to guide your way back home through the mountains. You could be a design-nerd and you want to own a little light designed by Olafur Eliasson.

Or you’re a Sudanese mother and you want to prepare your family’s meals under a safe and healthy source of light. Or maybe you have a young family in Berlin and you want a colourful way to teach them about sustainability.

Whoever we are, wherever we go, there is more that connects us than divides us. And one of the most important things that holds us together is that we all need light in our lives. Of course the greatest light we have is the one we all share: the sun.

Sometimes it’s nice to feel that the big wide world just got a bit littler.

Welcome to our little world:

www.littlesun.com

![]()

![]()

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

-

Gramazio & Kohler, the designers of this intricate lattice-like brick façade in Pfungen, in their native Switzerland, have observed that digital fabrication processes serve as a means of (re-)connecting architects with the act of making – and what material could be more appropriate for the task than time-honoured brick.

The structure is in fact a freestanding screen, which sits just in front of the former production hall of (guess what) a brickworks, now serving as a headquarters for construction company Keller AG Ziegeleien.

Designed using BrickDesign software, such complex geometry can be easily transported from Euclidean space to the solid world of construction thanks to the ROBmade process in which a robot places and glues each brick individually. This mode of precision production has become a reality thanks to the collaborative research efforts undertaken by Gramazio & Kohler, Keller AG Ziegeleien and ETH Zurich. But given that the development of the system took some seven years and the relative scarcity of such technology within an industrial context, the robots may not be coming for the humble bricklayer just yet. I (fs)

Photo and video © Gramazio Kohler Architects

-

Trapped by History

Focus on historical salvage

By Sara Faezypour, Sophie Lovell & Rob Wilson

Neues Museum, David Chipperfield Architects, Berlin, 1997-2009. (Photo: Jörg von Bruchhausen, © SPK / David Chipperfield Architects.)

-

Vintage is not just a trend found in fashion and coffee shops. Today successfully salvaging a building, keeping what Walter Benjamin might describe as its “aura” – with a touch of artfully preserved, authentic ruin aesthetic – has become an architectural genre in its own right. uncube presents a few selected examples.![]()

The Neues Museum refurbishment is a fine balance between old and new.

(Photo: Jörg von Bruchhausen © SPK / David Chipperfield Architects)

-

David Chipperfield Architects was founded by David Chipperfield in 1985. With offices in London, Berlin, Milan and Shanghai, the practice is known for the number of projects they have designed in a wide range of typologies. The Museo Jumex in Mexico City and the restoration of Palmengarten in Frankfurt are examples of completed works and some ongoing projects include the Nobel Center in Stockholm and the restoration of the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin. The practice has been awarded more than 100 international awards and citations, including Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) and David Chipperfield received the 2011 RIBA Royal Gold Medal and the Japan Art Association’s Praemium Imperiale in 2013 in honour of his lifetime’s work.

David Chipperfield Architects

Brick is an ancient building material, a collective witness to past events, testament to generations of builders in its layers of construction. The oldest brick yet discovered is some 7,500 years old and it wasn’t until the late 19th century and the advent of high-rise construction that brick’s limitations were increasingly reached and steel and concrete began to challenge its supremacy.

Whilst modernism held sway, many historic brick buildings were neglected, left to decay or destroyed in urban renewal schemes. It was only in the 1970s that attitudes began to change towards preservation and it began to be seen as a desirable goal, with new projects increasingly seeking to incorporate and renovate historic fabric where possible.

One of the most prominent examples of historical salvage recently has been David Chipperfield’s restoration of the Neues Museum in Berlin – where that city’s collections of Egyptian and Greek antiquities are on display – a project with which he rewrote the textbook on how to harmoniously integrate old and new. The Neues Museum, built by Friedrich August Stüler between 1843 and 1855, was severely damaged and partially destroyed during the Second World War and then left to rot for over sixty years. Chipperfield Architects, in collaboration with Julian Harrap, was appointed to restore it in 1997 and in 2009 the museum was re-opened. In particular, much of its original rough inner brickwork has been left bare where the original ornamentation and plasterwork was destroyed, and new volumes have been built using recycled bricks, ones clearly delineated from the old: meaning the architecture itself, as much as its ancient contents, is celebrated and displayed as a restored artefact, with all its historical patina laid bare.

Once describing his architectural philosophy as “accepting that we are trapped by history, and that’s part of the richness of culture”, Chipperfield’s process of restoration was to go room-by-room and space-by-space, deciding at each stage what could be kept, repaired or replaced if it proved beyond saving. Today the Neues Museum is one of the most successful examples of how to salvage a ruin, yet create something absolutely contemporary at the same time. -

The Ningbo Museum occupies an uninhabited plaza in the Yinzhou district where much of the 5,000-year-old city’s past has been erased. This bulky edifice does not feel at odds with China’s version of modernity: the more extravagant and eye-catching the better, but there is much more to it than meets the eye. Wang Shu, the architect is, ironically, an advocate of the preservation of Chinese architectural heritage. In an attempt to reanimate the site’s past, he constructed the museum from millions of roof tiles and bricks salvaged from the demolished villages of the region. Built using the “wa pan” technique, a traditional reconstruction method used by the locals following typhoon damage, the building’s main function is to preserve the historical Chinese artefacts in its galleries, but it also serves as a fitting memorial for the many ancient demolished structures that stood in the path of progress.

Amateur Architecture Studio

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The museum was built using bricks and tiles recycled from destroyed villages. Photo: Lv Hengzhong

Ningbo

History

Museum

A memorial in brick

to lost villages

MORE![]()

![]()

-

In the inner harbour of Duisburg, a former trade and transport hub of the city, lies the new NRW State Archive. The salvage here takes the form of conversion, and reclamation: a listed 1936 brick-clad warehouse has been transformed to store memory instead of goods: all the state’s archive material, previously scattered in different locations, has been gathered together under its one roof. This the architects Ortner & Ortner achieved by adding extra storeys to the old in the form of a massive windowless brick tower bursting out of the old roof of the warehouse and soaring 76 metres into the air. The huge new blank brick structure above the sealed windows of the old warehouse below, initially presents a forbidding and austere prospect, but one mitigated on approach by a highly ornate brick patterning and texturing of the tower – a hymn to the master bricklayer’s craft.

O&O Baukunst

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Overall views (Photo courtesy O&O Baukunst)

and detail view of the archive showing the masterful brickwork of the façade. (Photo: Flickr/Michael, CC BY-ND 2.0)

![]()

-

At King’s Cross, as part of a large redevelopment of old railway goods yards in central London, one of the remaining buildings, a listed granary, has undergone major conversion, restoration and extension to house one of the city’s leading art and design colleges. Originally built in 1852 to a design by Lewis Cubitt, the newly transformed complex by Stanton Williams architects has gathered students from the formerly scattered sites of Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design into a single campus facility. Whilst housing all the necessary facilities such as library, galleries and workshops, the shell of the six-storey former granary with its two transit sheds has been kept essentially as raw space intended to be occupied organically by students and staff, rather than proscribing any fixed use.

“A sense of history has been retained”, said partner Paul Williams, referring to the industrial past of the area: “When you walk through the building, you will be able to understand how it was used in 1851.” Whilst it looks magnificent, for many of its present occupants the general feeling seems to be that history could have made way a little more for the day-to-day needs of contemporary students.

Stanton Williams Architects

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

UAL Eastern Transit Shed showing the careful retention and restoration of 19th century brickwork. (Photo © Hufton + Crow)

UAL Central

St. Martins

History retained through organic occupation

MORE -

![]()

![]()

-

Capturing a moment that’s more than a little Schrödinger’s cat in nature, this photo sequence shows the twelve-second destruction of a chimney at the Henniger brewery in Frankfurt, brought down in a choking cloud of red dust.

The apparent elegance of the operation is misleading – ensuring a successful demolition takes more than lacing the interior of a structure with explosives. Breaking points must be calculated with absolute precision to bring the building down into its own footprint – (Transverse Shear Stress, Longitudinal Stress Force and The Bending Moment are the impressive roll-call of forces which act upon falling chimneys) – after which the rest is in the hands of gravity.

Such is the resilience of most types of fired brick that demolitions are hardly ever down to any deterioration of the bricks themselves, which can commonly be recovered and recycled afterwards, finding new purpose elsewhere. Until demolition day rolls around again… I (fs)Photo: Wikicommons/Amandajm CC BY-SA 3.0

-

Building in Brick 3/4

Sergison Bates

ArchitectsLondon, UK

London- and Zurich-based Sergison Bates architects use, write and think about brick a lot in their practice.

-

What do you like about brick’s qualities as a material?

»We like the inherent properties of brick and the scale of it. A brick can be held in the hand, yet used to create buildings of great size. The making of bricks has a direct relationship to what the Ancient Greeks considered the constituent elements of all things: air, fire, water, earth.

Bricks are also infinitely variable: their character depends on their components, the way they are laid, choice of mortar, size of joints. And, as it is built manually, a brick wall bears the imprint of the people that have built it.«Previous page: Public Library in the Flemish seaside town of Blankenberge, Belgium, 2011. The storey-high wall panels of blue-brown brick are laid in a bond with its vertical joint wider than its horizontal, designed to give a textile-like character to the wall. (All photos courtesy Sergison Bates architects)

-

Left and centre: Urban housing, Finsbury Park, London, UK, 2008. Here the brick, burnt-red in colour has flush mortar joints, designed to make each brick panel read as a monolithic element; right: Studio House, London, UK, 2004: a timber-framed structure on which the brick is treated as a coarse surface cladding, with a mortar slurry washed over its surface.

-

Sergison Bates was established in 1996 by Jonathan Sergison and Stephen Bates and joined by Mark Tuff as partner in 2005. They have engaged with all dimensions of architectural and urban design rather than focusing on narrow specialisms, and are currently involved in projects ranging from urban planning and regeneration to public buildings and housing in the UK and mainland Europe. A second office was opened in Zurich in 2010. Recent projects include the Nordbahnhof PaN Wohnpark housing project in Vienna (Österreichischer Bauherrenpreis 2014) and the transformation of a listed former brewery building in East London into a new undergraduate campus for Hult International Business School (RIBA National Award 2015).

The practice is committed to a research-based approach, which is supported by the partners’ academic work. Both founding partners have written and published extensively: their latest book, Buildings, was published by Quart Verlag in 2012.

sergisonbates.co.uk

How does brick function as a material climatically where you build?

»In London, the porous character of brick requires careful detailing. But there are centuries of experience to draw upon – after the Great Fire of 1666 it became the building material of choice. In Zurich, we are more cautious in employing brick. Whilst there is a wonderful industrial tradition, the Swiss brick industry is small, which makes it expensive to use. In Belgium nearly all our projects include brick. There, the brick culture is still very special. Building a brick wall in Belgium involves two phases: one person lays the bricks, and then someone else finishes the brickwork by pointing it.

« I

About Sergison Bates architects

-

![]()

![]()

-

Like most teenagers, Bishal Thing and his brothers struggle to wake up in the morning. But they have a good excuse. When their alarm signals the start of the working day at the Bhramhayani Mata brick kiln near Kathmandu, it is one forty-five in the morning.

Sixteen year old Bishal is awake first, urging Shankar, at eight the youngest of the brothers, to get up. They struggle to pull on socks and gloves caked in mud and stagger out of their tiny shack into the freezing night to begin the gruelling task of making bricks for the next fifteen hours. The working conditions Bishal and his brothers endure are shared by tens of thousands of labourers working in brick kilns across Nepal. It is an industry built on long hours, low pay and a system of debt bondage which binds workers to the brick kilns for months, and often years. In the worst cases, it may amount to modern slavery.

While the vast majority of these bricks are made for domestic use, a recent investigation by the Guardian newspaper established that bricks from kilns like the one Bishal works at have been used in a humanitarian staging area built by the UN World Food Programme, a multi-million dollar upgrade of Kathmandu’s international airport and a new Marriott hotel in the capital.

The massive earthquake which struck Nepal on April 25 only compounded the plight of these brick workers. Immediately after the quake, most labourers rushed back to their villages, unpaid, to check on their homes, while others were forced to carrying on working against their will. In Nepal’s brick industry, exploitation and slavery remain commonplace, even in the wake of an earthquake. I (Pete Pattisson)Photo: Pete Pattisson

-

Building in Brick 4/4

Onion

Bangkok, Thailand

Influenced by the rich heritage of brick temples in the country, Thai practice Onion are interested in both the craft and climate-control possibilities of brick, as their Design Director Arisara Chaktranon explains.

-

What do you like about brick as a material?

What are its unique qualities from your point of view?»We like brick as a module of material and construction because it is rustic and durable. It is common but not generic in Thailand. Brick colours reflect different localities and different modes of production. The beauty of constructing a brick wall is based mainly on the skills of craftsmen challenged by our designs. We are often surprised by their precision and the unexpected spatial effects, such as the constant movement of shade and shadows on the wall.«

Previous page: The Bric a Brac “wall holder” constructed from traditional Thai materials, which serves as both wall and storage facility; produced for Milan Design Week, 2015. (All photos courtesy Onion)

-

With their playful geometry, the walls at the entrance to the Sala Ayutthaya Hotel in Thailand (2014) were designed to frame the sky as guests approach the building and cast constantly changing shadows throughout the day. Whilst this outside space belongs to a new boutique hotel, it was intended to explicity demonstrate the deftness of traditional local brick craftmanship which can also be seen at nearby temples.

-

Onion is a Bangkok-based design practice founded in 2007 by Siriyot Chaiamnuay and Arisara Chaktranon. The two designers carry out a continuous exploration aimed at different needs for contemporary life styles. Onion brings the local craftsmen to explore the new techniques of using local materials. Together, they constantly push the boundaries of spatial designs in order to form a unified approach to retail and living experiences. The studio’s portfolio includes a variety of products ranging from interior objects such as handmade lamps, chairs and tables to architectural designs such as the Sala boutique hotels at various locations.

onion.co.th

Are there any particular references that you come

back to when using brick in your architecture?»Our main influences are the brick buildings of the Phutthai Sawan Temple in Samphao Lom. They were built in the fourteenth century by King Ramathibodi I of the Ayutthaya Kingdom. We are impressed by the brick layering patterns, the solidity of masses and the formal qualities of these buildings. They hold images of the past that we can identify with. You can see this particularly in our new hotel Sala Ayutthaya, which is sited near the temple.«

I

-

![]()

![]()

-

The Roman historian Suetonius recorded a claim by the Emperor Augustus that he found Rome “…of brick, but left it of marble.” This may have been true on the surface, but the vast structures that wowed your average captive barbarian, were – including Augustus’s own palace – still solidly brick at heart.

He built his palace on the Palatine Hill, the most central of the Seven Hills of Rome, and the site not only of his own birth but also of the city’s symbolic heart: the Cave of the Lupercal. Buried in its depths is where, so the myth goes, a female wolf suckled Romulus and Remus, legendary founders of the city. A possible candidate for this cave has recently been located, 18 metres down inside the hill, buried under an avalanche of brick, bearing witness to how the mound was extended up and out with palace after palace by succeeding emperors who favoured its siting commandingly above the Forum Romanum on one side and the Circus Maximus on the other – so many in fact that the very word “palace” was spawned from the Palatine’s name. I (rgw)Palatine Hill, Forum Romanum, Rome, Italy. (Photo: public domain)

-

In the Photo Booth with ...

Wolf D. PRIXThe “Baucooperative Himmelblau”, as it was originally called, was founded in 1968 aiming to liberate architecture from its functional confines and rectilinear grids by rendering space more dynamic, and if possible, overcoming gravity. Today Coop Himmelb(l)au is an internationally renowned practice with a distinctive signature still in its architecture. At the opening of an exhibition in Frankfurt of their latest projects, curator and critic Philipp Sturm met up with practice head Wolf D. Prix, the last of the original founders. Reluctant to set foot in a photo booth, Prix opted instead to stand in front of a large poster of his latest building: the European Central Bank (ECB) Headquarters in Frankfurt.

Interview and Photographs by Philipp Sturm![]()

-

Mr. Prix, in 1980, you penned your famous text “Architecture Must Blaze”, writing: “It must be precipitous, brutal, tender, obscene, sexy and heart-stopping.” Now, 35 years later, you have completed a skyscraper for the ECB in Frankfurt. What makes this building sexy?

The text was a statement calling for more emotion in architecture at the time. It doesn’t describe a building.

-

The new ECB headquarters is a lofty, deconstructivist glass and steel tower, which stands next to Martin Elsaesser’s Grossmarkthalle from 1928. It is primarily a high security structure. Can such a building relate at all architecturally to the city in which it stands?

The ECB building is complex, and as such is a symbol for the complex European community. The tower stands in a visual relationship with Frankfurt: it is visible from many points in the city, and vice versa. The view from the large atrium we positioned in the middle of the tower is always directed towards the centre of Frankfurt.

Which of Frankfurt’s other towers do you like the best?

Christoph Mäckler is a good friend of mine, so I opt for his OpernTurm. In general I find it fascinating, and rightly so, that Germany has a city that not only allows skyscrapers, but also insists on them.

-

Wolf D. Prix (*1942 in Vienna) co-founded the Baucooperative Himmelblau together with Helmut Swiczinsky and Michael Holzer. Holzer left the company in 1971 and Swiczinsky in 2001, making Prix the sole design principal of what is known today as Coop Himmelb(l)au. Prix studied at the Technical University in Vienna, the Architectural Association in London and the Southern California Institute of Architecture in Los Angeles.

www.coop-himmelblau.atAbout the Exhibition:

On the occasion of COOP HIMMELB(L)AU’s 47th birthday and until August 23, 2015, the German Architecture Museum (DAM) presents three of the studio’s recent projects: the European Central Bank Headquarters in Frankfurt (Germany), which was inaugurated on March 18, 2015, the Musée des Confluences in Lyon (France), which opened in December 2014 and the Dalian International Conference Center (China ) from 2012.

www.dam-online.de

Mäckler’s natural stone facades grow out of the buildings along the perimeter block, but the entrance to your twisting glass towers cuts through the historically listed Grossmarkthalle. It could be said that these two high-rises are architectural antipodes or opposites. When and how did you become friends with Christoph Mäckler?

We have always been friends. I have always maintained solidarity with quality. I was also very close to Hans Hollein, who, especially in his later years, did not particularly represent my notion of architecture. But this did not affect our friendship.

In your opinion, which skyscrapers deserve to be demolished?

I am against blowing up my colleagues. I -

Dieste, the brick and a certain ethos

By Florencia Rodriguez

![]()

-

Dieste, the brick and a certain ethos

By Florencia Rodriguez

![]()

-

![]()

Issue No. 36:

August 27th 2015

Still from “Electroma” directed by Daft Punk, 2006. (© Daft Life LTD)

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Less is a bore.«

Robert Venturi

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents

Details and views of a selection of Dieste’s projects including Cristo Obrero Church, the gymnasium in Durazno and the Montevideo Shopping Centre. (Photos:

Details and views of a selection of Dieste’s projects including Cristo Obrero Church, the gymnasium in Durazno and the Montevideo Shopping Centre. (Photos: