-

Magazine No. 39

Storage

-

No. 39 - Storage

-

page 02

Cover

-

page 03

Editorial

-

page 05 - 14

A Little Bit of Order

Sophie Lovell talks to Eero Koivisto of Claesson Koivisto Rune

-

page 16 - 17

Caging the Beast

Keeping Chernobyl leakproof

-

page 18

The Frankfurt Kitchen

Emancipation through rationalisation

-

page 20 - 25

Memory Palaces

Architecture for recollection in the age of forgetting by Fiona Shipwright

-

page 26 - 27

Homes for Things

Self-storage centres for stuff

-

page 28

Packing for Eternity

Tutankhamun’s 3,300 year-old trunks

-

page 29 - 35

The Invisible Museum

Elvia Wilk talks to Hans Ulrich Obrist about outing the archive

-

page 36

Systematically Stashed

The 606 Universal Shelving System

-

page 37

The Lives of Others

Tearing up the Stasi archives

-

page 38 - 42

Lest We Forget

Sophie Lovell & Sebastian Schumacher on the rise of the data centre

-

page 43

Tall Storeys

The ups and downs of the multi-storey car park

-

page 44 - 49

Ex Libris

Focus on national libraries

-

page 50 - 51

Our Friends Electric

The Tesla Gigafactory

-

page 52 - 54

Bookmarked

uncube's favourite storage-related books

-

page 55 - 59

In the Photo Booth with...

Shumi Bose, Jack Self and Finn Williams

-

page 60

Further Reading

-

page 61

Next

Iceland

-

-

uncube's editors are Sophie Lovell (Art Director, Editor-in-Chief), Florian Heilmeyer, Rob Wilson and Fiona Shipwright; editorial assistance: George Kafka; graphic design: Lena Giovanazzi, graphic assistance Janar Siniloo.

uncube is based in Berlin and is published by BauNetz, Germany's most-read online portal covering architecture in a thoughtful way since 1996.

Humans tend to be compulsive hoarders. In fact so much so that one wonders whether the architecture profession was driven not so much by the issue of shelter as the search for a solution to that very important question: where can I put all my stuff? We hang on to so much, allowing it to litter up our lives and our planet in the process – all because we think we might need it sometime.

Our “stuff” becomes more of an issue in an age where many tend to prefer their environments to look clean, refined and, above all, empty. We still can’t bear to throw anything away – but don’t want to see it cluttering up our space either. So we squirrel away our physical objects in cupboards and self-storage and pack our data objects away in the “cloud”.

Unless of course we’re talking about art, because here the interest in the archives and wunderkammers of art storage has made a dramatic return: all of a sudden what remains hidden in the cupboard seems far more interesting than what we are served up in display.

Welcome to the uncube Storage issue!

Please tidy up when you are done.

Cover image: Photo: Josef Shulz

-

![]()

An interview with Eero Koivisto of Claesson Koivisto Rune

by Sophie Lovell

-

Together Eero Koivisto, Mårten Claesson and Ola Rune make up the Swedish architecture and design practice Claesson Koivisto Rune. For the past twenty years they’ve worked together creating buildings, furniture and spaces according to their own particular pared-down approach. Sophie Lovell talked to Eero Koivisto about their influences, love of art, and how storage fits in with their gesamtaesthetic.

Previous page: exterior view of Inde/Jacobs Gallery, Marfa, Texas, 2015. This page: interior view of Inde/Jacobs Gallery. (Photos: Åke E:son Lindman)

-

You’re known for the clean, pared-down aesthetic of your furniture and architecture. It’s even been called “the epitome of the aesthetics of the new millennium”. What drew you to your particular form of reductionism?

In a way our aesthetics are a product of our interest in abstract art but also in Scandinavian and Finnish aesthetics. All three of us grew up in intellectual households, surrounded by post-war Scandinavian modernism or functionalism. You have to remember that this part of the world used to be very poor when other European countries were quite wealthy. In Sweden, for example, the Gustavian style was imported in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries from other European courts. But as we didn’t have the money to interpret it as expensively, the Swedes did a cheaper, simplified version – but it is really beautiful. Our own practice aesthetic is a kind of hybrid between functionalism and beauty, a bit like Vilhelm Hammershøi’s [1864-1916, Denmark] beautiful paintings of rooms. It doesn’t come from some fight for minimalism but is more an attempt to find a kind of functional beauty.

You’ve just completed a new gallery, the Inde/Jacobs Gallery, in Marfa, Texas, designed specifically to hold minimalist and reductive art by Donald Judd and others. It is a space that has to contain “things” i.e. art – and yet feels empty...

Well most spaces where you go to look at art are usually reduced in some way. To start a dialogue with an artwork you need to cut out the things happening around it.

We had all been to Marfa to look at the work of Donald Judd and others on several occasions already, and were very interested in the ideas these abstract artists had. It was a really nice commission to get.

![]()

Inde/Jacobs Gallery, Marfa, 2015. (Photo: Åke E:son Lindman)

-

So how do you go about creating the feeling of emptiness?

First of all, all three of us are extremely interested in art. We don’t just buy art for decoration. We always think about the art in the places we design, creating space to be able to focus on individual works. In this respect, what might look empty to somebody else looks full to me.

Do ideas coming out of the Bauhaus, of functional efficiency married to a simplified, spare aesthetic, also influence your work?

I studied the Bauhaus, just like everybody else, but personally was much more interested in the work of Luis Barragán, for example, whose work was, to my mind, warmer than European modernism, which was always slightly cold for my taste. I don’t mean bad, but kind of machine-like, using cold materials. Also Donald Judd’s works and his living spaces had a much more profound effect on how I approach what we’re doing. There are not that many things in his spaces, but they are definitely warm, not cold.

Do you still see a combination of form and function as a key to good design?

Judd said that the difference between art and design is that design must work – art not. Which I think is very good. It’s a bit stupid to make a chair you can’t sit in. But then again, what is a chair? Judd’s essay called It’s Hard to Find a Good Lamp is a good text on this subject.

When we’re working on one of our designs or buildings, I think there are several things going on in. Firstly there’s a strong sense of logic and then maybe a little bit of order, because it’s easier to see beauty if there’s some kind of order around it. We try to have clarity – I really like it when the architectural plan is very clear.

![]()

Råman Studio, South Sweden, 2002. (Photo: Åke E:son Lindman)

-

Also, one thing that a lot of people say about our work is that our places are very calm when you experience them in real life. But we come from Sweden, so I think there’s also a side that is joyful, maybe even funny sometimes. Like the work of the ceramicist Stig Lindberg, it’s kind of pared down and ordered, but with a softness to it – a happiness, like with the Kelly chairs we did for Tacchini in 2013.

With modernism this idea of cleanness, clarity and ultimately total transparency – that everything can be seen – was projected outwards onto modernist space: from Loos to Mies and beyond. Of course the stuff of real life intervenes to prevent this. I wondered if you see your work – which uses a lot of concealed, seamless storage space – as a pragmatic solution to living the simple life whilst still accommodating the stuff of the everyday.

Well I’m sitting here talking to you in my little four metre square library. In it I’ve one big Dieter Rams 606 bookcase filled with music, cookbooks, novels and other stuff.

![]()

There’s no particular order to it: lots of books are piled on top of each other with little knick-knacks standing in-between. But the room is a pretty minimal room. What I’m trying to say is that of course we put a lot of storage in because we all have kids and grew up in big families. You need storage for life, but it doesn’t always need to be hidden.

Gaston Bachelard in his 1958 book The Poetics of Space referred to attics and cellars and even cupboards and drawers as the dream spaces in a house. I was interested as to whether you feel that it’s now the finishes and surfaces that function as the blank canvasses against which we project our dreams?

We don’t take away these dream spaces, but sometimes you just can’t put a cellar in a house because the clients don’t have the budget – it’s expensive! I simply like having a lot of storage because it is really good to store things! (laughs)

“Ida Reading a Letter”, painting by Vilhelm Hammershøi (1864–1916).

-

I’m thinking more about your commissions, like the Apartment with Brass Cube in Stockholm you did in 2013, which is all about seamless concealed space. At the high end of the market is it not the definition of luxury to seem like you have nothing?

Ha ha, I would say that only a very tiny part of the world’s wealthy live like that – a homeopathic-like quantity. Anyway my personal experience of the wealthy is that they don’t want the pared-down interiors that we make, they want big fluffy Italian ones. They tend to be conservative and have a lot of things on show.

But that particular client in Stockholm got so involved in the project she actually quit her job and started studying architecture! It’s a big apartment but not as expensive as it looks. We did not fill it with expensive furniture, for example. It is just a really, really beautiful space.

Maybe expensive is the wrong word, but it does look precious – in a good way – precisely because, for example, in the kitchen the utensils and foodstuffs are hidden.

I was in Japan once in a 1970s bar in Osaka, with just a bar top, nothing else. We ordered something and the bartender took all the ingredients out from storage, put them on the bar and then started making our drinks in front of us. It was a very intense experience. Very concentrated. Of course I understand if people like having all their pots hanging around, but in a kitchen everything gets dirty so you have to wash them before you cook. That’s a bit impractical. We have a similar kitchen and my wife and I put away everything after we use it, even the toaster.

![]()

-

![]()

![]()

Apartment with Brass Cube, Stockholm, 2013. (Photos: Birgitta Wolfgang Drejer)

-

You put your toaster away?!

Yeah. Some of our friends think we are overly fanatical about that. But I have never seen a single toaster nice enough to leave out.

Perhaps the discussion is another one: that we’re not allowed to talk about beauty in everyday life because everything has been so over-theoreticised. When we make storage, we make it to store things. For my paintings, there’s a long wall outside this library where I’m sitting, of which the library door is part, which is about 13 metres long. On this wall are only four works, no more. You could easily put 30 pieces on it but because there are four, they become important. They are not just decoration, and every day I see them I think about them. But of course I need somewhere to store all the rest of the artworks when they’re not up – which I do in a wardrobe. It was made to have clothes in, but mine is full of art!It sounds like this relationship between things and space and storage for you has a lot to do with discipline.

One of our first assignments after finishing college was renovating an old schoolhouse for the Swedish ceramicist Ingegerd Råman and her artist husband Claes Söderquist. We learned a lot from working with them. They were an older couple who lived in a normal Judd-ish way – and were very precious about their things. I once asked: how come you have so many nice things? Everything in your home is beautiful. They said: it’s simple, you just decide never to buy anything you don’t really like. And from that point it takes about eight years. So I did and it works.

![]()

City Apartment, Stockholm, 2013. (Photo: Åke E:son Lindman)

-

![]()

How do you deal with the need to identify function with form in a stripped down aesthetic when you remove all the signifiers showing you how to use something – say in a fitted kitchen with no visible handles?

That’s because it is very difficult to find nice handles! Personally I don’t think we make it more difficult for people by taking away visible handles in a kitchen. They are there, just recessed. But if there is a built-in handle like this, then it’s really important that it feels good to your fingers when you open it. We spend a lot of time on things like that.

What about this idea of the house itself becoming the furniture? Storage used to be in sideboards, chest of drawers and so on, but today it is often embedded in the fabric of the house itself.

We really liked Japanese spaces when we were at college. All three of us spent time in Japan whilst studying and they’ve always had built-in storage. We also had a great teacher at school who did a course with us on the Shakers: how they put things together, They also had storage built into walls. It’s nice because, like you say, the apartment becomes the furniture.

-

The architect and designer Eero Koivisto was born in Finland but grew up in Sweden. Educated at Konstfack University College of Arts, Crafts and Design in Stockholm, Aalto University School of Art and Design in Helsinki, and Parsons The New School for Design in New York, he founded Claesson Koivisto Rune in Stockholm together with Mårten Claesson and Ola Rune in 1995. This started as an architectural practice but has since become a multi-disciplinary office with equal emphasis on both architecture and design. Project categories include hotels, homes, shops, offices, exhibitions, kitchens, sanitary ware, tableware, glassware, furniture, textiles, tiles, lighting, electronics and candy.

Built projects have included the Tind Prefab house collection for Fiskarhedenvillan, Widlund House on Öland, Örsta Gallery building in Kumla, Sfera Building culture house in Kyoto and Nobis Hotel in Stockholm, whilst products have been designed for more than 80 international manufacturing companies from Arflex, Asplund, Blueair and Boffi to Skandiform, Skultuna, Swedese, Tacchini and Wästberg.

claessonkoivistorune.se

Does this throw much more emphasis on the detailing and the material finish?

It’s much harder to make a more pared-down space because you have to think so hard about how to make the joins and the craftsmanship. You spend a lot of time looking at the details. We have normal oak floorboards in our own home and the skirting is really tiny, about one centimetre wide, and angled towards the wall. My wife and I spent weeks designing that skirting – now we use it in all our projects. When you look at it, it’s almost not there.

Do you think your architecture reflects a desire for living a simple life, even helps people fulfill this?

One of the good things about the modern world is that there are many possibilities. There is not just one aesthetic or one idea, but many. What we do is maybe not for everybody. The really nice thing about the internet, Instagram, Facebook or whatever, is if you are into something really nerdy and specialist, you can connect with other people into that too. This just happens to be what we’re like. We might not be something for everybody, but we definitely mean a lot to some people. I

![]()

Kelly L Chair by Claesson Koivisto Rune for Tacchini, 2013. (Photo: Andrea Ferrari /Tacchini)

-

![]()

![]()

-

If storage is an act of containment, then there is perhaps no more dramatic example than the ongoing endeavour to contain the radiation still being emitted from the Chernobyl nuclear power plant following the devastating power surge that hit Reactor 4 on April 26, 1986. That same year, Soviet authorities scrambled to put in place a shelter that would stem the radioactive tide, a cloud of which spread across a swathe of Europe in the immediate aftermath.

This could only ever be a short-term measure; upon completion it was estimated that the structure would have maximum shelf life of 30 years, a blink of an eye in half-life terms, given the site is expected to remain hazardous to human life for the next 20,000 years. But now, despite a decade of delays that has seen the precarious 1986 structure dangerously corroded by rainwater, efforts to build a replacement are underway.

Due for completion in 2017, the new arched shelter, managed by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and implemented jointly by Bechtel, Batelle Memorial Institute and former staff of the decommissioned plant, reaches 93 metres at its highest point and is something of an engineering feat. It is being built on foundational rails in two sections that that will eventually be rolled together over the old shelter, snugly encasing it and its carcinogenic cargo in a concrete and steel “sarcophagus”. The new structure has also been designed to withstand anything Mother Nature wants to throw at it during its expected lifespan of 100 years, including a Class 3 tornado. I (fs)Video and photo courtesy of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

-

The Frankfurt Kitchen

This, the first modern fitted kitchen, was designed in 1920 by Margarete Schütte-Lihotsky. 10,000 of them were mass-produced as part of Ernst May’s huge social housing programme in Frankfurt, tasked with “winning freedom from the irrelevant clutter of outmoded habits of thought and old-fashioned equipment”.

Schütte-Lihotsky refined her design by conducting time-and-motion studies of kitchen tasks, inspired by the ideas of Taylorism on scientific management and work efficiency. She saw her design as being emancipatory and was convinced that “women’s struggle for economic independence and personal development meant that the rationalisation of housework was an absolute necessity.” p (rgw)

Detail of an original “Frankfurt Kitchen” taken from the Römerstadt estate, Frankfurt, 1927, and now in the collection of the Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge, Berlin. (Photo: Armin Herrmann)

-

Memory Palaces

Architecture for recollection in the age of forgettingText by Fiona Shipwright

Illustrations by Janar Siniloo

![]()

-

We no longer need to remember anything it seems. The transference of our (biological) memories to (digital) memory has effectively liberated us from the need to train, strengthen and exercise our powers of recall. Responsibility for information we might once have “kept in mind”– a shopping list, a travel route, a phone number – is more often than not allotted to our personal digital devices. Take these away and what hope does the digital age human mind have?

![]()

-

Potentially more than you might think. Architecture – specifically our experience of it – plays an important role in the construction and retrieval of our biological memories. Enter here that most evocative of terms from the world of mnemonics: the Memory Palace. Reintroduced to popular imagination via the investigative antics of Sherlock Holmes and the escapist fantasies of Hannibal Lecter, the idea of a mental palace filled with memories is a mnemonic technique originally developed in Ancient Greece and Rome that allowed users to translate, organise and recall large amounts of information in a form that would “stick” – a necessity in the pre-print era.

![]()

In antiquity a distinction was made between “natural memory”: the standard, everyday mode of remembering; and “artificial memory”: that which can be trained using such methods.

Sometimes referred to as the Method of Loci (Latin for “places”), the idea is deceptively simple: in order to store – and retain – information, ideas are located in a spatial environment that can be mentally walked through. A building with differing rooms works particularly well as it presents the mind with a fixed navigation and narrative to latch onto. Ideas that need to be remembered are placed as “objects” in specific rooms, the more bizarre (read: memorable) the pairing, the better.

-

For example, if you need to remember to make an appointment with the vet, you might leave a cheetah sprawled across a chaise-lounge in that snug alcove in the hallway of your “palace”. Need to remember to book a table at a sushi restaurant next week? Try filling the dining room’s marble fireplace with bright pink salmon. In this way, simulacra – that is images, forms – are given a “physical” anchor in loci – places. To remember them, you just have to go for a stroll through the palatial corridors in your mind.

In human terms, our contemporary neglect in flexing our memory muscles is a relatively recent development.

![]()

In 1966, post-print but pre-digital, the English academic Frances Yates, tracing the Art of Memory in her eponymous book, already pertinently remarked that: “We moderns[…]have no memories at all […]But in the Ancient World, devoid of printing, without paper for note-taking or on which to type lectures, the trained memory was of vital importance.”

If the print revolution heralded the beginning of the end for our memory retrieval capabilities, then the post-digital world is arguably deteriorating our abilities to a state of amnesia.

-

![]()

Or should that be overstimulation? We are forgetting once again, but in a markedly different way. Digital media grants us the power to retain seemingly all the information we want; yet this very ability is now producing such a vast volume that it’s becoming impossible navigate. The act of accessing a great store of memory is a very different thing to actually remembering.

Perhaps this is why the language of architecture has endured to describe digital data storage – “memory architecture” – mapping drives and creating libraries. In using the same parlance are we perhaps once more trying to translate the ephemeral (once human thoughts, now digital data) into a more easily graspable form – just as the ancient method of loci attempted to do? And, if we are in effect creating digital memory palaces – complete with the concrete language of architecture – in place of our mental memory palaces, are we at the same time revealing a desire to retain the comfort of the physical qualities of built space? If this is the case, why are we not taking more care in the structure of our memory aids: why a cloud and not a palace?

Architecture discourse has long distinguished between generic space and specific place – why then our increasing inclination towards cyberspace? It’s not as though we haven’t already created spatially “formed” realms on the internet (Second Life etc.) but these are representations, or, to be more accurate, simulations of the world – any function they serve as an aid to remembering tends to be by chance rather than design.

-

Instead, when it comes to the things we daily use the internet for: looking up and retrieving the information stored there, we are effectively doing this in the architectural equivalent of a non-place. Just as trying to pinpoint memories placed in some vast featureless lobby will not work, neither, research suggests, will the human memory easily retain answers to questions asked into an empty search bar, which pops up instantaneously before disappearing back into the ether.

Yet this is increasingly how we learn about the world. Which begs the question, for the sake of our human memories, should we be demanding better architecture for digital memory? The continued use by modern-day “memory champions” of the method of loci seems to demonstrate that our minds, or at least the parts concerned with memory, really do work best spatially – this is how we encounter and negotiate the world. But that’s not how we’ve built the main tool we now use to pilot it.

Should our digital infrastructure – that born of the idea of a world-wide, connected web after all – be better at showing us actual connections, especially now that earlier limitations such as dial-up connections have been lifted. Do we now need architects of memory?

Key to the functioning of the Memory Palace, is the idea that nothing is ever lost, merely “misplaced”, a further parallel with the internet as the greatest human archive of all. If we now find ourselves creating digital memory palaces in order to navigate our mental memory palaces, does this take us yet further away from that which we are trying to pin down in the first place – human experience?

We have handed over our memories (and by default, increasingly our identities) for storage on the internet but somewhere along the way it seems we may have all but forgotten the art of remembering. p

![]()

-

![]()

![]()

The demand for storage spaces is on the rise, especially in dense capitalist metropolises. People need more and more space to keep the things they don’t need all the time but are too good to throw away. Since garages, cellars or attics are not part of the modern apartment typology and the contemporary working world demands ever increasing flexibility and mobility of its freelancing workers, the question becomes a simple one: where can I put my stuff?

An increasingly popular answer is “self storage”. It’s a service without any service, because basically you have to do everything yourself. Self storage stations are mostly big ugly buildings, purely functionally and completely closed to the outside like a department store, yet stuffed to the seams with secure units ranging from one to 100 square metres in size where your valuables are kept safe from fire, water, wind and thieves. -

It’s already a familiar typology in suburban areas, yet with the growing demand it is slowly creeping into the centres of cities like New York, London, Berlin and Paris.

In Berlin, this trend has taken a new twist in the form of a big pre-fab GDR apartment block which has been turned into self-storage units. So whilst it is hip in the hauptstadt to live in buildings that were originally factory or storage spaces (“loft living”), the buildings that were actually designed for people to live in are now becoming storage spaces. Take that, architects. I (fh)Photos: Philipp Lohöfener

-

Packing for Eternity

Howard Carter reported seeing “wonderful things” on first shining his light into Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922. Despite previous botched robbery attempts, the majority of the tomb’s contents still remained intact, complete with everything any self-respecting Pharaoh might need for a journey across the underworld to the afterlife.

But packing back in 1323 BC must have been a nightmare. Just keeping Tutankhamun himself in fine fettle for the journey meant that, after embalming, his corpse was encased in a nest of three gilded coffins, one stone sarcophagus and five timber shrines. Meanwhile his vital organs were packed away in their own canoptic chest. The rest of King Tut’s travel trunks included caskets for utensils, chests for linens, jars of oils, ointments, scents, foods and wines, chariots for hunting, even a boat, with everything guarded by the dog god Anubis and a couple of sacred bulls for good measure. A case of travelling might not light. I (rgw)A gilded bust of the Celestial Cow Mehet-Weret and travel trunks as found in King Tut’s tomb, 1923. Photo: © Griffith Institute, University of Oxford. Colourised by Dynamichrome.

-

The Invisible Museum

Hans Ulrich Obrist on outing the archiveInterview by Elvia Wilk

Photography by Joël Tettamanti -

![]()

![]()

As a curator celebrated for projects that have mined the archive, Hans Ulrich Obrist tells Elvia Wilk about why he thinks curating has more to do with archives than collections and how art storage itself has become a principal player in the twenty-first century museum.

-

Let’s start our discussion about storage by talking about objects. Are you a collector of objects yourself?

No, I’m a curator, not a collector. I curate objects, but I also curate quasi-objects, non-objects and hyper-objects. The history of art from the nineteenth century to the 1960s is above all a history of objects, but since the 1960s, thinking of Lucy Lippard’s landmark book The Dematerialization of Art, we also have a history of non-objects. And we have Michel Serres’ theory of the quasi-object, an object which only gains significance when interacted with. And now, living in the Anthropocene, we know that everything is interdependent, and that leads us to a history of hyper-objects, as Timothy Morton calls them.

It’s not that objects are now obsolete; on the contrary, but they’re only one aspect, one possibility. Thinking about archiving and storage in the twenty-first century, we need to take into account these many dimensions.![]()

-

The word “curate” stems from the latin word curare meaning to cure medically, or to care for, as in tending a sacred space. But there are many other meanings to curation: sorting, connecting, selecting, displaying. Would you say you are more concerned with these other aspects of curation than with caretaking or preservation?

The Latin root of curare is very interesting because as you say, caring about the artwork and the artists is part of curating. Another interesting [linguistic] similarity is curiosity. I think curiosity is something of an engine, a drive, to the profession of curating. In a way a curator is a generalist: there are many aspects of what one does, and caretaking is certainly an important part, but it’s not only the caretaking of an object.

JG Ballard once told me that curating, for him, was about making junctions. You can think of junctions between objects, between non-objects, quasi-objects, hyper-objects – and of course between people. Curating is also about bringing people together.Could you describe an exhibition of yours where junctions were made between the archive and the contemporary?

In Design Real at the Serpentine in 2009, the German designer Konstantin Grcic exhibited a series of design objects that were not luxury or elitist products but great design for all, like an airplane seat. All these objects were crated, brought to London and displayed on plinths.

-

In the central room was each object’s history, giving its context, its ramifications… almost like Bruno Latour’s Actor-Network-Theory applied to curating.

One of the first museum projects where storage wasn’t marginalised but given centre stage, was Rem Koolhaas’ unrealised project for MoMA called Charette. It’s a very interesting proposal in which he’s saying that it’s important we think about storage because it’s the unknown, the invisible. Italo Calvino talks about the Invisible City – you could say storage is the invisible museum. Ninety-nine percent of museum archives are part of this invisible realm inaccessible to the visitor. The visitor has to wait until the curator decides to make the art accessible.

A different way of addressing the archive is in the new Broad Museum by Diller Scofidio + Renfro, which I just visited. In the stairway there’s a sudden unexpected appearance of a window giving you free view into the storage area. It’s something you usually don’t see.I’ve always thought of you as a collector of interactions, of junctions, as you say. With your ongoing conversations, your interviews with artists and others, you’re effectively building an archive of artists and their work through documentation rather than artefact. Is this an archive or is it a collection?

I’ve always thought curating had more to do with archives than collections, having been inspired by Harald Szeeman, who was an incredible archivist. The collector’s endeavour is often to think of “what’s missing” [from the collection], with me, the archive comes out of research. It’s not the by-product of curating, but something done in tandem with the exhibition. There’s a reciprocal relationship between my activity as author and curator and the archive.

Of course deciding what to archive, or store, is to decide how you want to remember things. You’re looking backwards with an archive, but you’re also deciding what will matter in the future.

One exhibition where we tried to bring all this thinking together was for the Swiss Pavilion at the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale. We wanted to pay tribute to Cedric Price and Lucius Burckhardt. Cedric was very interested in this relation to the archive – he resisted objects, resisted the freezing of his work. How could we archive someone who didn’t want to be archived? How could we do a dynamic kind of archive?

I asked Herzog & de Meuron to work on this storage-archive project because with their design for the Schaulager in Basel they’d already addressed this idea of visitor as active participant in an archive process – and they’d been Lucius’ pupils.

-

![]()

-

Hans Ulrich Obrist (b. 1968, Zurich, Switzerland) is Co-Director of the Serpentine Galleries, London. Prior to this, he was the Curator of the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. Since his first exhibition World Soup (The Kitchen Show) in 1991 he has curated more than 250 shows.

Obrist’s recent publications include Lives of Artists, Lives of Architects, Ways of Curating, A Brief History of Curating, Do It: The Compendium, and The Age of Earthquakes with Douglas Coupland and Shumon Basar.

I was also inspired by the Living Theater of Julian Beck, which removed the wall between actor and spectator. This led to the idea of getting the artist Tino Seghal involved, and we started to develop this dynamic archive together. We had a storage facility in the centre, with all these archive boxes, and as soon a visitor entered, a trolley with an archive box would be pushed towards them by an architecture student who would talk to them about it. So the visitor would discover the archive’s contents through dialogue. The more people came, the more trolleys were rolled out. We tried to make the storage the key protagonist: it was a sketch for how an archive could work every day.

What’s interesting is that the way institutions are beginning to engage questions of storage, through revealing mechanisms of art storage and display, mirrors original strategies of institutional critique. Has the job of institutional critique, of examining archival policies, now become the job of the museum itself?

I think it’s vital for the twenty-first century museum to find ways for archives to be alive‚ to no longer be secondary. There are so many extraordinary archives in the world that are dormant. The dynamic engagement with archives is an important part of the necessary and urgent “protest against forgetting”! There isn’t necessarily more memory within the current explosion of information – amnesia might be at the core of the digital age, which makes the quest of the archive more important. I

![]()

-

Systematically Stashed

Shelving is still the mainstay of storage solutions for all things non-digital – it is hard to imagine any domestic or commercial interior without at least one shelf. When it comes to flexible shelving design adaptable to a variety of spaces, the “system” is king. In 1960, the German designer Dieter Rams designed a component unit system for a company called Vitsoe that is so flexible and functionally efficient it is still in production today: the 606 Universal Shelving System. It doesn’t even need walls for installation – just a ceiling and a floor, like here in the offices of recent RIBA Stirling Prize winners AHMM architects in London, where it is used to store their model archive. The British designer Jasper Morrison called the 606 “the endgame in shelving design”. I (sl)

606 Universal Shelving System by Dieter Rams for Vitsoe. (Image courtesy Vitsoe)

-

The Lives of Others

As the German Democratic Republic fell into disarray during 1989, the Ministry of State Security (Stasi) found itself stranded. Without direction from the government, employees of the intelligence organisation began tearing up documents from its vast archive of information, destroying the evidence of the State’s extensive spying on some six million members of its own population.

News of the shredding spread quickly and the Stasi headquarters in East Berlin became a centre of protest and occupation. Crowds stormed the building to stop the destruction, saving over 100 shelf-kilometres of filed information. The shredded files were also salvaged and a team of “puzzlers” continues working to this day, painstakingly reassembling documents and images to reveal a more complete picture of life as watched over by the GDR Big Brother. I (gk)Photo: Daniel Stier

-

![]()

The rise and rise of the data centre

By Sophie Lovell & Sebastian Schumacher

-

The internet forgets nothing. Everything is saved – nothing is thrown away and it all needs storing somewhere. IBM estimates that we generate some 2.5 quintillion bytes per day, that 90 percent of the world’s stock of data is less than two years old and that this volume is currently doubling every 18 months. This exponential growth is creating an exponential storage problem as well as an exponential energy problem: where are we going to put it all and where will all the energy come from to keep our memories “alive”?

Previous Page: Verne Global, Iceland. (Image courtesy Verne Global) This page: Facebook data centre in Luleå, Sweden. (Image courtesy Facebook)

-

So where does all our data get kept? It may be digital but it still takes up space, and it takes up a great deal of energy too. As long ago as 2007, according to The Economist, we began experiencing a data housing crisis. The same source states that the amount of data generated surpassed the available storage space. In 2008 American households alone generated 1,200 Exabytes (1018 bytes) of data. Add industry and science output to that figure (for example: when the new Square Kilometre Array (SKA) telescope in South Africa and Australia goes online, in the next decade, astronomers expect to process ten petabytes of data from it every hour, or 1015 bytes) and you start to get an idea of the size of the issue involved.

Global tech giants such as Google, Facebook, Microsoft and Amazon are all building data centres at an incredible rate to cope with the demand for digital space. Facebook alone expects to have five new centres in operation by 2017. Apple has recently announced plans for new facilities in Denmark and Ireland. And don’t forget all the other providers: Deutsche Telekom, for example, completed Germany’s biggest cloud back-up centre in Saxony-Anhalt in 2014, containing 30,000 servers and which is already expanding.

So there is a quiet building boom going on of windowless, high security homes for our collective memory – housing everything from kitten gifs to government secrets. A new architectural typology is growing with it, where the well-being of bits and bytes takes priority over living occupants. This also means a new vernacular of citizen-less urban sprawl developing as these server farm hosting facilities are placed near power supplies or where there is space to generate their own power.

This is because another major consideration when it comes to data centre location is cheap and clean energy. Our brains consume more energy and generate more heat than most of the rest of our bodies.

-

So it goes with servers. Data centres are responsible for an estimated two percent of US energy consumption. According to The Guardian, each of Facebook’s data centres uses enough energy to power 30,000 US homes. Greening data storage is therefore a big issue. Thankfully there are signs of change in this respect. Apple’s new server farm in North Carolina, for example, uses on-site biogas fuel cells and acres of solar panels to power it and they claim that all of their server farms worldwide are now powered by renewable energy. Facebook too is building a 17,000 acre windpark to power its Fort Worth plant in Texas.

In terms of location, countries like Norway, Sweden, Iceland and Canada are also finding themselves highly desirable as low environmental temperatures can help save a fortune on cooling and local water sources mean cheap hydroelectric power. Facebook already has their first server farm in Europe in the small town of Luleå, Sweden to take advantage of this, claiming it to be “the most energy-efficient computing facility ever built” and they are currently building a second. Iceland too has two huge data centres: Verne Global and Advania Data and is investing in attracting more big companies to join them.

Finding detailed‚ reliable information about data centres is difficult since just about all the big companies are rather less than fully transparent in this area and many facilities are shrouded in secrecy. Which leads to another interesting potential driver for data centre location: data sovereignty. Amazon Web Services, Microsoft and IBM have all recently announced new centres in India to serve the big local consumers there – but the question still remains: under whose jurisdiction is the data held?

Google data centre in South Carolina, USA. (Image: Google/Connie Zhou)

-

This is an issue that has gained considerable traction in Europe where the European Union has raised the issue of the privacy and security of their citizen’s data on foreign servers, something that is particularly relevant in the wake of Edward Snowden’s NSA revelations.

So unless the internet can learn to forget, or we can find more efficient storage solutions, this is an exponentially messy memory storage problem that’s not going away. And it will most likely come closer to home when we decide that, despite all the promise of the world wide web creating a global community, we may actually prefer to have these giant “clouds” – anything but fluffy ones – on the ground nearby so we at least have the feeling they are under local jurisdiction.

Get used to server farms, this is an architectural typology that is going to become as common as the agricultural kind in the not too distant future. I

Water pipes for cooling the servers at Google's data centre in Georgia, USA. (Photo Google/Connie Zhou)

-

![]()

Tall Storeys

In 1930s Chicago – the home of the skyscraper – the only way was up. This revolving “Car Parking Machine” had a valet service that boasted it could recognise and return your Model T within 55 seconds. Up until the 1970s, multi-storey carparks – stacking cars off increasingly congested streets – remained desired, even signature, civic landmarks. However their often inelegant hulks, typically prey to graffiti and petty crime, increasingly became symbols of urban decay and dysfunction. Today much inner city parking has been driven underground – but some recent multi-storey carparks, like Herzog & de Meuron’s 1111 Lincoln Road in Miami Beach, might just signal an expressive new renaissance for this building type. I (gk)

![]()

-

![]()

![]()

Focus on national libraries

By George Kafka & Fiona Shipwright

-

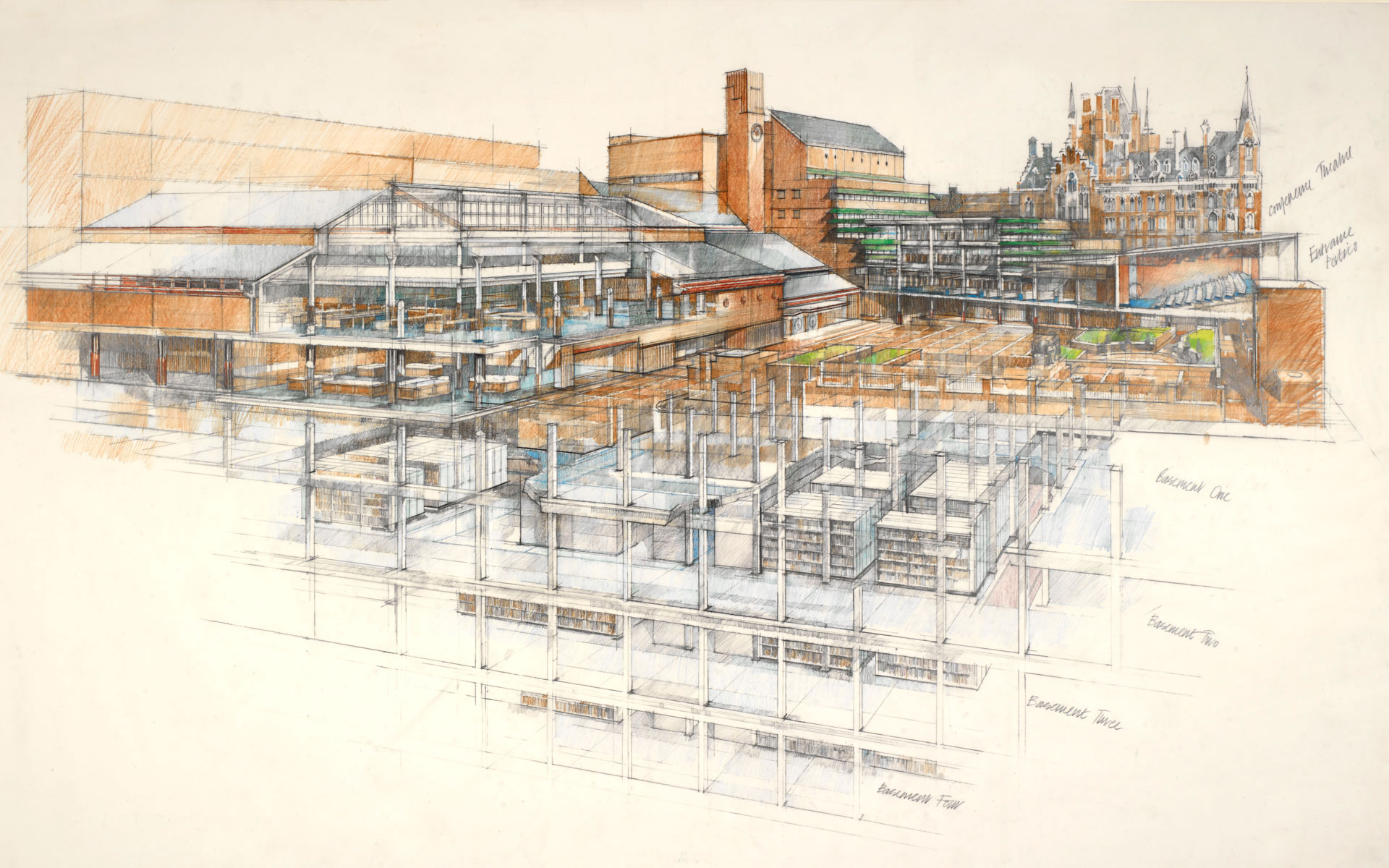

Previous page: So what does a vast Alvar Aalto-esque brick pile on the Euston Road say about Britishness? Sectional drawing through the British Library from Ossulston Street by its architect Colin St John Wilson, c.1991. (Image courtesy British Library)

National libraries are the central repositories of the books and documents produced over a nation’s history and so, in a sense, repositories of national identity itself. Their architecture therefore has often been seen as needing to reflect that sense of identity.

But how do you build a national library for a new nation? What happens to a library and the information it holds when a nation ceases to exist? And what does nationhood even mean in a world where national borders are superseded by a digital continuum? uncube’s bibliophiles popped out to the library in search of some answers.![]() British Library Reading Room (Photo: Paul Grundy)

British Library Reading Room (Photo: Paul Grundy) -

![]()

Photos: Gerald Zugmann

Bibliotheca Alexandrina, Alexandria

—

Ptolemy’s Royal Library of Alexandria in Egypt was a built manifestation of the maxim “knowledge is power”. It held papyrus scrolls filled with information gathered from the far corners of the ancient world. But the library with its vast collection of documents was destroyed in a fire in 48 BC, just prior to Egypt’s incorporation into the Roman Empire.

Almost 2,000 years later, Alexandria has once again became home to a showcase library that acts as both a centre for learning and a memorial to its ancient predecessor. Designed by Snøhetta in 1989 and completed in 2001, the Bibliotheca Alexandrina’s disc-like structure appears to rise out of the Mediterranean Sea and is wrapped in hand-carved stone adorned with pictographic script, a tribute to the ancient texts lost in the flames. Among its facilities is the Manuscripts Center, an academic institution that is preserving rare manuscripts in digital form to create an indexed (and fireproof) record of Arab and Islamic heritage. -

![]() Images courtesy of The Colin Laird Project Ltd.

Images courtesy of The Colin Laird Project Ltd.![]()

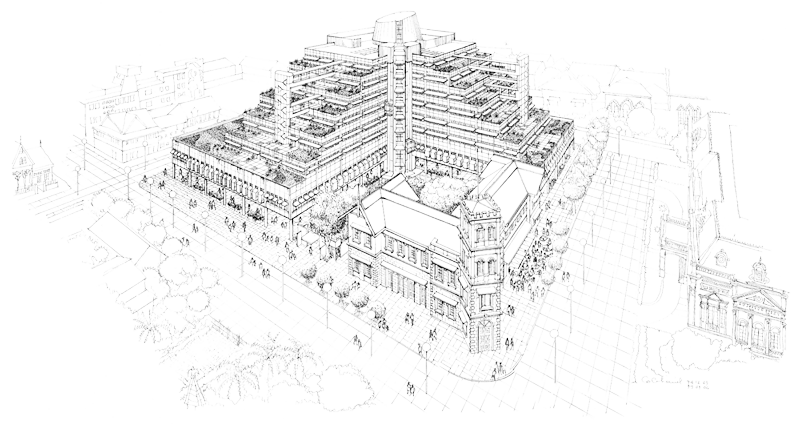

Trinidad & Tobago National Library, Port of Spain

—

Colin Laird’s national library building in Port of Spain, Trinidad, provides a clear example of how this typology can serve as a metaphor for a nation. Although completed in 1999, over thirty years after the country’s independence, this optimistic and inclusive library complex represents the pre- and postcolonial history of the island, incorporating architecture from both sides of this juncture.

Occupying a whole city block, the scheme juxtaposes the colonial – a former fire station – with Laird’s tiered pyramid-like structure. When viewed from street level, the latter appears to rise triumphantly out of the Victorian gables of the former, reflecting Trinidad and Tobago’s own ascendancy out of colonial rule.

The two buildings are also interspersed with public plazas and open walkways, in line with Laird’s civic-minded approach and his critique of the exclusionist, authoritarian nature of typical colonial architecture and urbanism. -

![]()

Photos: Wolfgang Thaler

National Library of Kosovo, Pristina

—

The value of inclusivity for a repository of the written word is particularly important in a country where language – and its suppression – has been inextricably woven in struggles for national identity. The National Library of Kosovo has undergone seven name changes since its initial inception 71 years ago as the Regional Library of the Autonome Province of Kosovo, a reflection of the shifting nature of nationhood in the region.

The current building dating from 1982 (last renamed in 2014) was designed by Croatian architect Andrija Mutnjakovic, and remains the present day home of the institution. Its spectacular exterior comprises an array of 99 domes and cubes, looking something like a Balkan take on a Metabolist fantasy. Despite the backdrop of conflict against which the building has stood (in 1999 it was used as a strategic base by Serbian forces), its design actually embodies something of a conciliatory spirit, referencing the vernacular of both Serbian and Albanian traditions, whilst the cube and dome motif is representative of the region’s historical Byzantine and Ottoman roots.

-

![]()

Photo: Seungjun Im

National Digital Library, Seoul

—

If the etymology of the word library (“book room” or “chest”), refers to a very physical way of thinking of book storage then it’s not surprising that a national library concerned with the very non-physical realm of the digital, should invent a new term: welcome to the “dibrary”.

Purposely located directly alongside its more traditional sibling, Seoul’s National Digital Library is intended by the architects to act as a “digital doormat” to the former. Designed and completed in 2009 by German architects Bolles+Wilson and Korean firm Junglim Architects, the building channels a key facet of South Korea’s character, namely its position as a world-leading technological producer and innovator. The national identity associated with it is less tied to the content it stores but rather more concerned with the facilities it offers. I -

![]()

![]()

-

Tesla Motors recently became Tesla Energy and are in the process of constructing a huge Gigafactory in Storey County, Nevada. By 2017 it will begin producing batteries for their all-electric vehicles as well as their new Powerwall domestic battery packs, all designed for one purpose: global liberation from the fossil fuel industry.

According to Tesla’s CEO Elon Musk, the 400,000 square metre factory was “born out of necessity”, after the company projected battery requirements for 500,000 vehicles alone in the year 2020. When running at full capacity, it is expected that the Gigafactory site will be producing more lithium ion batteries annually than were produced worldwide in 2013.

If that isn’t impressive enough, the entire roof of the structure will be covered in solar panels which, when combined with wind and geothermal energy, will produce all the energy required on site. By reducing waste, containing most of the production under one roof, and employing innovative manufacturing techniques, Tesla hope to reduce the cost of battery packs – and their sleek sports cars – by an estimated 30-70 percent.

So far so green; it still remains to make lithium ion battery technology in itself more environmentally sound. Although Tesla also promises 100 percent on-site recycling, as far as energy storage is concerned, this is still very much the beginning of the story. But it looks like not a bad start. I (gk)Image courtesy Tesla Motors

-

Archive Fever

Jacques Derrida

Translated by Eric Prenowitz

University of Chicago Press, 1996

128 pages

ISBN-13: 978-0226143675

![]()

We’ve perused the bookstacks of an infinite library to bring you uncube’s recommended reading on storage. On the shelf are shipping containers, prisons, and water towers – time to think inside the box.

![]()

Derrida’s Archive Fever investigates the language and processes of the archive and was prompted by a lecture he gave at the Freud Museum in London, itself – based in Sigmund Freud’s last home – an accumulated archive of a life. Derrida pays particular attention to our need to leave something (physical) behind: “there is no archive without consignation in an external place which assures the possibility of memorisation, of repetition, of reproduction, or of re-impression”. p (fs)

-

Prisons

Editor: Kyle May

CLOG, 2014

160 pages

ISBN-13: 978-0-9838204-9-9The Box

How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Bigger

Mark Levinson

Princeton University Press, 2008

400 pages

ISBN-13: 978-0691136400

![]()

![]()

This themed issue of CLOG has collected essays, interviews and illustrations examining the architectural history of mass incarceration. Through Ai Wei Wei’s haunting description of permanent surveillance while imprisoned in China to Michael Sorkin’s plea for architects to stop designing execution chambers, architecture’s complicity in the dehumanisation prisons engender becomes clear. Far from rehabilitative, as Jacob Reidel’s opening essay points out, “...the modern prison remains a space for storage and removal”. p (gk)

![]()

This highly entertaining book, written by economist Mark Levinson, introduces us to the history of the standard shipping container. He traces this from the first container voyage in 1956 to the worldwide phenomenon of “containerisation” primarily driven by entrepreneur Malcolm MacLean, who turned “the box” from a rather impractical idea into the standard tool of a globalised, standardised economy which every ship, train, truck and eventually port had to adapt to in order to stay competitive. p (fh)

-

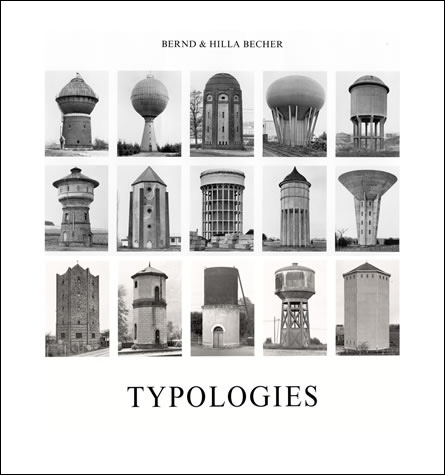

Typologies of Industrial Buildings

Bernd and Hilla Becher

The MIT Press, 2004 (reprint)

228 pages

ISBN: 978-0262025652The Library of Babel

from Collected Fictions

Jorge Luis Borges

Translated by Andrew Hurley

Penguin Books, 1999

576 pages

ISBN-13: 978-0140286809

![]()

![]()

Architects have been drooling over blank, functional forms since the birth of modernism, and this compendium of Bernd and Hilla Becher’s monochromatic grids of photographs of industrial buildings – including many storage structures from grain elevators to water towers – is a visual feast of dumb façades. Seemingly objective but packing a powerful emotional punch, it’s like looking at an identity parade of a lost industrial age, making the Bechers pioneers of ruin porn too. p (rgw)

![]()

The infinite library that Jorge Luis Borges’ created in his short story The Library of Babel has fascinated scholars and paper architects alike since its publication in 1941. He describes a structure for storing all possible combinations of a twenty-five-letter alphabet and thus all possible language and knowledge. Like the shadowy wanderers in the library’s endless spaces, the reader too gets lost in its hexagonal chambers in search of texts revealing “the fundamental mysteries of mankind”. p (gk)

-

In the Photo Booth with ...

Shumi Bose, Jack Self and Finn Williams

It’s a busy time for Shumi Bose, Jack Self and Finn Williams who were recently announced as the co-curators of the British Pavilion at next year’s Architecture Biennale in Venice, commissioned by the British Council. Bose and Self are launching a new bi-monthly architecture magazine the Real Review on the back of a successful Kickstarter campaign, while Williams runs a practice Common Office which works between planning, politics and the public. And what with their various teaching and writing commitments, we were lucky to catch and cram them all into a photo booth in Venice to get the low down on their upcoming pavilion.…

Interview by Rob Wilson![]()

-

Congratulations on being selected to represent Britain at next year’s Architecture Biennale in Venice! Your proposal Home Economics focuses on the family home as the “frontline” of British architecture – picking up on Alejandro Aravena’s Biennale theme. Why do you think the home is such an urgent battlefield in architecture?

Thank you! In Britain, as elsewhere, economic ideology has produced an artificial shortage in housing. This crisis is the result of strong beliefs about the role of the State (that it should not build) coupled with perverse regulations and lack of incentives for the private sector to provide sufficient volumes of new homes. The standard of living for British people is falling, while the cost of living is rising, and housing is central to this process.

However, it’s not just a problem of supply. We’re experiencing a paradigmatic societal shift: family structures, gender roles, power relations and class formation, patterns of work and leisure, not to mention mass migration and the end of both the civic realm and domestic privacy. So much is in flux and the way we design homes has fundamentally failed to keep up with the realities of how we live and work today. -

You’re proposing to show a series of 1:1 environments to “challenge the status quo and propose new futures for the British home”. Can you explain what you hope to show with these?

The British are conservative when it comes to the home, from how they’re decorated to how they’re built and paid for. We hope to explore different models of finance and tenure, non-traditional furniture and appliances, new formal and functional typologies. The key is not simply to be critical. Architecture exhibits that are critical tend to concentrate on raising awareness about a condition, but rarely make a proposition for an alternative. That positive vision is very important to us.

-

You’re planning to collaborate with a team of architects, artists, designers and developers on this, which reminds me of the collaborative teams behind the “This is Tomorrow” exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery in London in 1956. We often look back to the post-war period and see it as a time of great experimentation in the way we lived. Do you think it is possible to be as radical in thinking about housing now as it was then?

It’s not only possible, but already happening. It’s just not as obvious because it’s not on such a large scale of production, but radicality and innovation are still strong. It’s also important to view this in context. Those full-scale projects of the 1950s themselves drew inspiration from earlier: the 1920s Werkbund expos and housing projects like the Weißenhofsiedlung and pavilions and installations like those by Mies or Bruno Taut… which in turn drew on older models, dating back to Gottfried Semper’s “primitive hut” installation at the 1851 Great Exhibition in London. So there is a long heritage of this kind of immersive proposition as a tool for experimentation and seduction, reinterpreted in each era. Home Economics is certainly not nostalgic, it aims to be first of all propositional.

-

Shumi Bose is a writer, editor, and teacher based in London. She is senior lecturer for contextual studies in architecture at Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design and assistant lecturer at the Architectural Association. She is co-founder of the REAL foundation and co-editor of the Real Review, to be launched in 2016. She has held editorial positions at the Architect's Journal, Blueprint, Strelka Press and Afterall, and has contributed to publications such as TANK, Volume, and PIN-UP. In 2012, Bose was one of three curatorial collaborators working with David Chipperfield for Common Ground, the main exhibition at the 13th International Exhibition of Architecture at the Venice Biennale. Recent publications include Real Estates (with Fulcrum, Bedford Press, 2014), Places for Strangers (with mæ architects, Park Books, 2014), and Models Ruins Power 1 (Kommode Verlag, 2014).

real.foundationJack Self is an architect and writer based in London. He is co-founder of the REAL foundation and co-editor of the Real Review, to be launched in 2016. His has been a contributor to Architectural Design, The Guardian, New Philosopher, 032c and Dezeen, amongst other publications., while his book Real Estates: Life Without Debt (Bedford Press 2014), now in its second printing. He is contributing editor at the Architectural Review, and was previously associate editor at Strelka Press (2012-13). Jack also founded Fulcrum, a free weekly based at the Architectural Association. As a designer he has previously worked for amongst others Ateliers Jean Nouvel in Paris and London (2008-09). His current clients and partners include developers and housing trusts, as well as academic and public institutions like the Victoria & Albert Museum (2015).

real.foundationFinn Williams is an architect-turned-planner based in London. Williams worked for Rem Koolhaas in Rotterdam and General Public Agency before setting up Common Office, an independent practice working with planning, politics, and the public. His writing has been published in journals and magazines including mono.kultur, Hunch, and Volume. Williams teaches ADS2 at the RCA with David Knight and Charles Holland, is External Supervisor for Spatial Practices at Central St Martins, and Specialist Urban Design Advisor to the Bartlett School of Architecture MArch Thesis programme. Among other roles Williams is vice-chair of the Tower Hamlets Design Review Panel. In 2014 he founded NOVUS, a thinktank for public sector planning. Finn is currently working on a new social enterprise to embed talented young designers within local authorities.

commonoffice.co.uk

Do you think that architects need to be more proactive and propositional again in suggesting ways for how we live? Have we perhaps been living with a reaction to the perceived failure of many of the “big” solutions proposed for housing in the post-war period and the demonising of the modernist architect?

If the Starchitects have achieved anything, it is that the public now trusts architects to design large scale, mass housing again. That’s one positive to be taken from projects like Ole Scheeren’s Interlace, or the redevelopment of London’s Battersea Power Station. If the failures of the Welfare State in 1980s Britain were sometimes attributed to brutal, unsympathetic and dogmatic architects, that stereotype has waned. Architects are perceived as innovative and thoughtful designers. There is, however, a rising awareness that the systems that architects operate within are no longer fit for purpose. I

-

FURTHER READING

Blog LENS10 Dec 2015

Things Best Left Unfound

Archive of Archives by Julian Rosefeldt

Blog Lens02 Dec 2015

Inner Sanctum

Gesche Würfel's photographs of New York Basement Sanctuaries

Blog Comment24 Nov 2014

Running on Reserve

Architectures of the Reservoir: Inside the Bauhaus Lab 2014

Blog Lens16 Dec 2015

Dam Fine

Carsten Meier's new photographic typology of dams

Magazine Case Study22

Oh Well

Indian Stepwells

Magazine Interview15

Protein Streams

Interview with Carolyn Steel

Search our archive! -

![]()

Image: “Reykjavik Series” by Olafur Eliasson, 2003

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Form follows feminine.«

Oscar Niemeyer

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents

Images courtesy of The Colin Laird Project Ltd.

Images courtesy of The Colin Laird Project Ltd.