-

Magazine No. 40

Iceland

-

No. 40 - Iceland

-

page 02

Cover

Iceland

-

page 03

Editorial

Iceland

-

page 05 - 07

Northern Flights

Leifur Eiríksson Terminal, Keflavík International Airport

-

page 08

No Sleep Till Breiðholt

Housing, horses and hip hop

-

page 09 - 16

Wish You Were Here

Arna Mathiesen asks: Refinancing Iceland with tourism – but at what cost?

-

page 18 - 31

Spaces Create Bodies, Bodies Create Space

An essay by Ólafur Elíasson

-

page 32

Home Turf

Iceland's ancient rural vernacular

-

page 33

Tin Skins

Reykjavík's corrugated cladding

-

page 34 - 38

Icelandic Domestic

Focus on post-independence houses by George Kafka

-

page 39

Notes from Nowhere

William Morris' road trip

-

page 40 - 42

The Road Less Travelled

Route 1/Hringvegur

-

page 43

Giving Shape to Space

The geodesic genius of Einar Thorsteinn

-

page 44 - 51

The Harp That Sang

The saga of Reykjavík's Concert Hall by Sophie Lovell & Fiona Shipwright

-

page 52

In the Round

A fishy factory

-

page 53 - 55

Some Like It Hot

Blue Lagoon Spa and Clinic

-

page 56

Further Reading

-

page 57

Next

Zvi Hecker

-

-

uncube's editors are Sophie Lovell (Art Director, Editor-in-Chief), Florian Heilmeyer, Rob Wilson and Fiona Shipwright; editorial assistance: George Kafka; graphic design: Lena Giovanazzi, graphic assistance Janar Siniloo.

uncube is based in Berlin and is published by BauNetz, Germany's most-read online portal covering architecture in a thoughtful way since 1996.

In September 2015 uncube sent an editorial expedition team out to Iceland to get under the skin of one of Europe’s most fascinating and enigmatic geographical outposts.

We fell in love of course, as did nearly a million other visitors to the island this year, but tried hard not to be too blinded by the beauty. We talked to architects, artists (well, one in particular), historians, planners and other locals in an attempt to form a picture that went beyond the postcard view.

The snapshot we present to you here is by no means comprehensive. It is about the architectural mood of the moment: an attempt to grasp the confluence of influences that have led to a nation, always used to living on the edge – surviving in the face of weather, isolation, eruption or invasion – to yet another point of dramatic change as it shifts into being a global tourist destination.

Welcome to the 40th issue of uncube!

Particular thanks for this issue go to: Pétur H. Ármannsson, Peter Cachola Schmal, Steve Christer, Ólafur Elíasson, Halldór Guðmundsson, super/collider, Guðmundur Ingólfsson, Camilla Kragelund, Sebastian Schumacher, Sony Deutschland and Hjálmar Sveinsson.

Cover photo: Sig Vicious

-

![]()

Northern Flights

Leifur Eiríksson Terminal,

Keflavík International Airport

Date: 1980-87

Architects: Garðar Halldórsson,

Birgir Breiðal and Sigurður GíslasonClient: Government of Iceland

-

Unless you are into long, rough boat journeys, the first stop on any trip to Iceland is, of course, Keflavík International Airport, the largest of the nation’s thirty-three airports – although the term “airport” is perhaps a little misleading since many of them are little more than rough-hewn landing strips. Arriving at Keflavík, rather than diving straight off the plane into the coach to the nearby Blue Lagoon spa as so many tourists tend to do, it’s worth taking a moment to appreciate the thickset temple to aviation that is the Leifur Eiríksson Terminal through which you pass.

The building is named after an Icelandic explorer – commonly referred to as the Viking Leif Ericson – who is believed to have discovered North America five hundred years before Christopher Columbus. The name is a fitting tribute, considering that Keflavík Airport was first built as an airbase by the US military during World War II.Previous page: photo courtesy Ozzo Photography. This page: photo by Guðmundur Ingólfsson.

-

After the war, civilian passengers wanting to fly internationally continued to pass through what remained a military air base until 1987, when the Leifur Eiríksson Terminal was completed by state architects Garðar Halldórsson, Birgir Breiðal and Sigurður Gíslason.

The Terminal’s heavy concrete structural elements are offset by its open and skylit passenger lounges and tessellated tubular steel roof construction, bookended by the cosmic stained-glass designs of artist Leifur Breiðfjörð. As compactly grand as it is, Keflavík is struggling with the exponential tourism boom that saw 1.2 million visitors pass through its doors in 2015. To ease the load, a new airport masterplan has been drawn up by Oslo-based practice Nordic, which will add a third runway and double the airport’s passenger capacity by 2040. I (gk) -

Turn your back on the picture-postcard streets of central Reykjavík, head out of town towards the southeast and you will come across Breiðholt. This somewhat unloved suburban neighbourhood sprang up in the late 60s to help house the city’s expanding population in the kind of prefab apartment blocks that have since become synonymous with urban decline.

Breiðholt is indeed the closest thing to a “ghetto” in Iceland. The prevalence of low-income groups, single parents and a proportionally high immigrant population have made it the target of social stigmatisation from some corners of society and it often plays a starring role in gritty music videos and feature films, such as the 2006 monochrome crime drama, Börn.

But Breiðholt has never shone quite like it does in the video for hip hop duo Úlfur Úlfur’s 2015 single Brennum Allt. The video, directed by Magnús Leifsson, features frontman Arnar Freyrd riding around Breiðholt on a native horse, as well as three drooling St Bernards in a convertible plus a bit of Icelandscape thrown in for good measure. You’re welcome. p (gk)

No Sleep Till Breiðholt

Turn your back on the picture-postcard streets of central Reykjavík, head out of town towards the southeast and you will come across Breiðholt. This somewhat unloved suburban neighbourhood sprang up in the late 60s to help house the city’s expanding population in the kind of prefab apartment blocks that have since become synonymous with urban decline...

![]()

Photo courtesy Magnús Leifsson.

-

![]()

Wish

You

Were

Here

Refinancing Iceland with tourism – but at what cost?By Arna Mathiesen

Illustrations by Friðlaugur Jónsson![]()

-

![]()

The Iceland-born architect and author Arna Mathiesen shares her view on the post-crash changes affecting her homeland and how the current all-out drive to entice more visitors to help replenish the state coffers is having as profound an effect on the infrastructure and architecture of the city centre as the earlier boom and bust.

Even today, departing and arriving is no small effort when it comes to Iceland. It was quite a feat in the ninth century to even find the country, lying as it does hundreds of kilometres from anywhere across rough seas. Settlers managed nevertheless to start whole new lives and for several centuries their descendants kept contact with the civilisation they left behind. In the early thirteenth century, after internal conflict weakened Iceland it became subjugated to Norway, which in turn was united with Denmark. Colonised and poor, most of the locals existed pretty much in isolation for a long time until Iceland finally regained sovereignty after the First World War, on December 1‚ 1918, followed eventually by full independence in 1944.

Despite the distance, more people are visiting Iceland now than ever before. The number of tourists almost doubled from 493,000 in 2009 to 997,000 in 2014. According to Arionbank’s estimates, 1.5 million are expected next year and an extraordinary two million in 2018.

Of course there have been many other visitors to Iceland before and since. Some of them, such as William Morris and W. H. Auden, even found the experience worth chronicling (in Icelandic Journals and the poem Journey to Iceland respectively).

Recently I listened with interest to a Norwegian architect describing his first visit to Reykjavík and how he hadn’t appreciated it until after he’d driven around the entire island, experiencing the way the buildings cling to hillsides, turning their backs to the northern winds, engaging in just enough dialogue with each other – but not too much – like occasional passers-by. Only then did Reykjavík start to make sense to him standing out as a special and fascinating type of urban fabric.

Previous page: Hallgrímskirkja Church, Guðjón Samúelsson, Reykjavík, 1945-1986.

-

![]()

But that was before the building bubble, which led to financial meltdown in 2008, which in turn led to all the island’s banks having to be restructured from scratch. It was a boom fuelled by a finance sector pushing loans for expensive buildings and infrastructure, and shaped by dreams from the 90s, of global cities competing to attract creative, mobile populations who would come to live in shiny new high-rises and pay to enjoy culture in slickly designed objects like the giant Harpa concert hall. For Iceland’s modest population of just 350,000, this also meant the costly expansion of infrastructures, such as a new highway system around Reykjavík, intended as a grand entrance for visitors into what was planned to be a new tax haven: a capital of global finance.

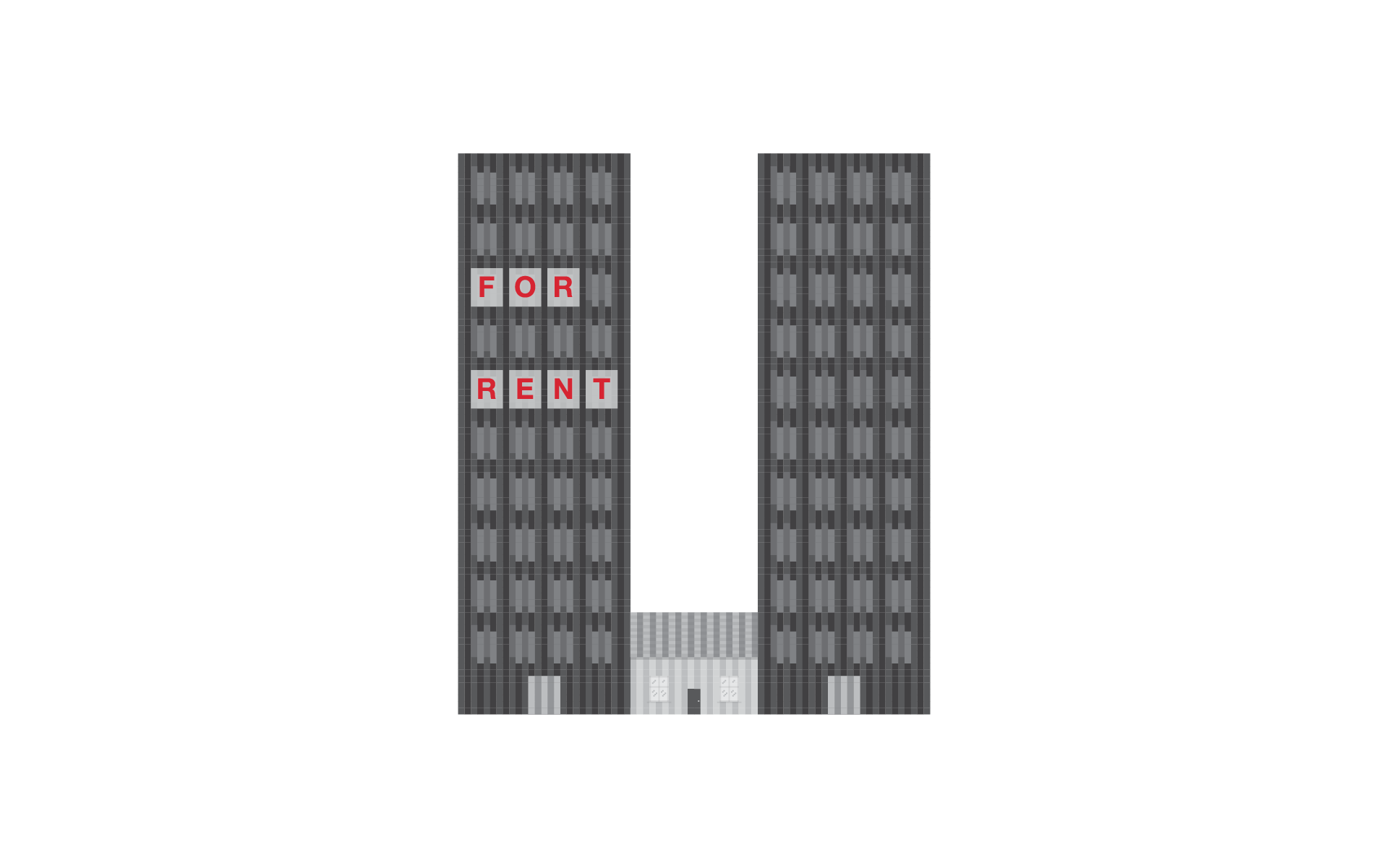

The urban transformations of the noughties went hand in hand with a new influx of foreign nationals, though this didn’t play out entirely according to plan. Instead of creative workers occupying sleek buildings, the new residents were mainly construction workers from the Baltic countries and Poland who came to participate in the boom and then chose to stay on despite the recession that followed the crash, albeit in less glamorous neighbourhoods. While ideas can be exchanged for others if they don’t work out, newly built buildings tend to stay put. One of the remnants of the “global city” strategy that was already completed before the crash is a series of apartment towers by the waterfront rising dozens of stories above the old(ish) low-rise city centre (only a handful of its buildings are more than 100 years old), blotting out the views northwards to Esja mountain.

-

![]()

As the crash fades into the past‚ the “corporate subjects” (individuals or groups organised in holding companies) have re-emerged; people who invest in domestic architecture, not to live in it themselves, but for speculation and profit alone. So towers keep getting built. Many Icelanders, architects in particular, grieve for the loss of the character of the old city they once knew. Even if priorities have changed since the crash, obsolete masterplans still set the premise for new buildings that will dwarf the fine-grained city fabric, because developers threaten court action to secure compensation for any “theoretical” losses if earlier agreements are overridden.

The exponential growth in the number of tourists is a special challenge in this context. Since 2005 the number of overnight stays by guests has increased by over 146 percent (5.4 million in 2014 up from 2.2 million). The city centre is rapidly transforming into a hotel haven. Even though many existing buildings have gained new life, others are being extended or torn down and rebuilt larger, in order to hike up the total rentable square metreage.

Accommodation booked online through sharing economy platforms such as Airbnb or similar, is also an increasingly popular option amongst tourists and backpackers alike. It was estimated in June 2015 that some 4,100 private rooms in the capital were listed on such sites – the equivalent of all guesthouse and hotel rooms combined. This means some four percent of all Reykjavík apartments are rented out to tourists (compared to 0.4 percent in Berlin). Despite or perhaps thanks to the publicity generated by its recent natural and economic catastrophes it seems as if the whole world is seeking a resting place in Icelandic living rooms.

-

![]()

»The city centre is starting to feel more like a northerly version of the Costa del Sol.«

![]()

-

In place of occasional wanderers‚ lively hordes of selfie-stick-wielding travellers dressed in brightly coloured outdoor clothing now drift further and further across the island’s delicate landscape‚ in search of an ever more exotic experience. Some locals see this also as a sign that the world has finally woken up to how fantastic Reykjavík city centre itself is, although the increased traffic there is more due to the fact that it is where almost all the hotels are. Either way the city centre is starting to feel more like a northerly version of the Costa del Sol. Spurred on by government branding campaigns, whoever wants to come to Iceland is courted and welcomed to the centre of Reykjavík with open arms.

While tourists bring profits for some, they also bring disadvantages to others. The municipality gains little direct income from them, while bearing increased infrastructural burdens. The city centre, which was the only place in town with a certain balance in terms of density, is now being over-developed, whilst the rest of the city, which could really benefit from densification, is being ignored. In other words, this central densification makes the peripheral sprawl that resulted from the boom – a political taboo of the last seven years – look like an even bigger and all the more urgent problem to address.

In addition, the profit from tourists’ overnight stays comes at the expense of a desperate shortage in the rental market. Local long-term tenants can’t compete with travellers paying per night, and rental prices have increased over 29 percent since 2011. Meanwhile speculation in residential space has triggered a new real-estate bubble, with house prices up by 23 percent in the same period.

As a result, and despite the rise in economic growth, many locals are embarking on yet another set of travels, heading to neighbouring countries in order to find a brighter future and work to earn enough to pay their mortgages back home. Meanwhile, the jobs generated by the tourist industry will likely be met by guest workers from abroad.

-

![]()

»Many Icelanders, architects in particular, grieve for the loss of the character of the old city they once knew.«

![]()

-

Arna Mathiesen grew up in the outskirts of the Reykjavík Capital Area, where the intersection between the urban and the wild was her playground. She spent a year studying philosophy and art history in her native Iceland, before embarking on her architectural education abroad, as this was not available in her home country at that time. She received a BA in Architecture at Kingston Polytechnic in the UK, studied architecture and sculpture in Oslo for a year and in 1996 completed a M.Arch at Princeton University.

Together with Kjersti Hembre, Arna is a founding partner of April Arkitekter AS, an architectural practice and research unit based in Oslo, with projects ranging from furniture to large housing estates and urban developments.

Arna recently led a case study on the Reykjavik Capital Area before and after the financial meltdown for The Oslo School of Architecture and Design. She was also the main editor of the recent book: Scarcity in Excess – The Built Environment and the Economic crisis in Iceland, published by Actar.

www.aprilarkitekter.no

Scarcity in Excess – The Built Environment and the Economic crisis in Iceland

Arna Mathiesen

Actar, 2014

250 pages

ISBN-13: 978-1940291321

issuu.com/actar/docs/scarcity

But is it always necessary to meet demand, howsoever it comes, with drastically changed infrastructure? Other lightly populated yet alluring destinations could be instructive here. The Kingdom of Bhutan, for instance, allows only a handful of heavily-taxed tourists to enter at any one time, claiming its present infrastructure can only support limited numbers, but that the tax income generated will help expand this.

While Bhutan’s policy appears to value gross national happiness over gross national income, in the case of heavily indebted Iceland one might conclude that it simply can’t afford not to do whatever it takes to refill the coffers – no matter the long-term price. The question is whose coffers are being filled? Your choice of host and the produce you buy next time you visit Iceland will decide.

![]()

And if you do visit soon‚ look out from Reykjavík city centre towards the old harbour and you will notice a rather unpleasantly gaping hole in the ground in front of the elaborate and well-proportioned façade of the Harpa Concert Hall, designed by a world famous artist. Consider now exchanging the view of this Ólafur Elíasson façade for that of a luxury Marriott hotel and shopping mall (due for completion in 2018), a project intended to cover 15 billion Icelandic Krona’s worth of the debts left behind from the construction of Harpa. Welcome to Iceland – enjoy the view! I

-

![]() Text and photography by Ólafur Elíasson

Text and photography by Ólafur Elíasson -

The Danish-Icelandic artist Ólafur Elíasson has a deep and close relationship with the natural landscape of his homeland and the thread of its influence clearly runs through his work. Here, for uncube, he shares a selection of his own images alongside three short films, personal glimpses from his most recent trip to Iceland last summer. His accompanying text explains his “embodied” approach to photography.

Previous page: photo from “The large Iceland series”, 2012. Video: “Travel log”, Iceland, 2015.

All media courtesy the artist; neugeriemschneider, Berlin; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York. -

We often think that we see everything, but our eyes are only one small part of our sensory apparatus. When we look at a thing, we think we see the real thing, but we don’t. We see a representation. Similarly, we tend to see the landscape as something static, as an image. When we walk, we generate space and make time physical. If I walk up a mountain, for example, it becomes more real. If I fall in the snow, it becomes very real. But if I lie in the snow and look down the mountain at the landscape, it looks like a postcard again. What I see resembles my expectations of what a landscape should be. It is similar to what I have seen elsewhere. My photographs of Iceland try to reflect a different way of seeing, an embodied approach to photography. The photographs and videos collected here reflect the body and space and scale, a space related to your body.

-

“The large Iceland series”, 2012.

-

“The volcano series”, 2012; 63 C-prints; detail.

-

“The volcano series”, 2012; 63 C-prints; detail.

-

You become more easily aware of how your senses function in a landscape than in urban space, which is arguably where we spend most of our time. My perception of landscape is more physical because it takes time to walk through a landscape. That’s because I can feel and measure my body in relation to my surroundings in a way that’s impossible in urban spaces, which generally have more going on in them – cities are full of narratives and signs, and the built environment concentrates on controlling people’s interactions more. Moving around a city or through a landscape always carries with it a certain level of staging or management. In cities especially, our surroundings are planned in order to manage our experiences. There is a long tradition of designing spaces to direct movement. Safety measures eliminate surprises and create predictable surroundings. The city’s social potential, on the other hand, lies in the less predictable, multipurpose spaces, which let you enjoy the hospitality of presence.

-

“The hot spring series”, 2012; 48 C-prints; detail.

-

“Jokla series”, 2004; 48 C-prints.

-

To a certain extent, my photographs play with traditional compositions. They have foreground, background, and middle ground, and I may place a mountain right at the centre of the photograph. As series, the photographs work together as studies. They suggest movement and plurality by documenting the same phenomenon many times over. While I try to portray the natural phenomena in a personal way, it is systematic at the same time – a kind of mapping. This approach shows how an image reflects our relationship to nature. It lets me play down my own personal perspective so that the viewer’s gaze plays a more active role.

-

“Iceland series”, 2004; C-print; unique.

-

“Mirrorstage for Merce”, 2004; colours photogravure.

-

“The hut series”, 2012; 56 C-prints; detail.

-

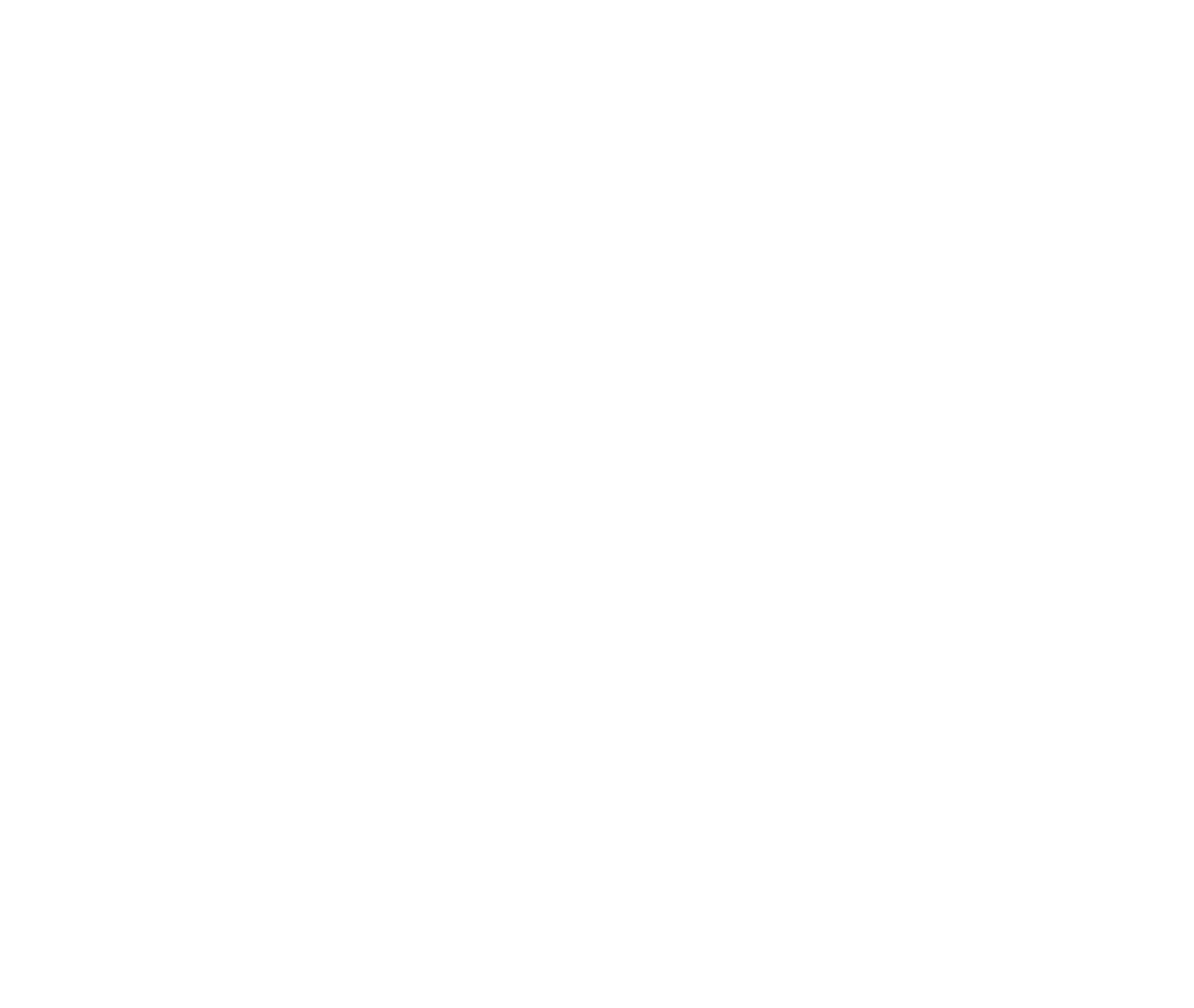

Artworks clockwise from top left: “Your emergence (blue to orange)”, 2012; “Empathy compass”, 2011; “Colour experiement no.66 (cyanometer)”, 2014; “Life of a planet”, 2015.

Ólafur ElíassonÓlafur Elíasson was born in 1967. He grew up in Iceland and Denmark and studied from 1989 to 1995 at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. In 1995, he moved to Berlin and founded Studio Olafur Eliasson, which today encompasses some ninety craftsmen, specialised technicians, architects, archivists, administrators, programmers, art historians and cooks.

Since the mid-1990s, Elíasson has realised numerous major exhibitions and projects around the world. In 2003, he represented Denmark at the 50th Venice Biennale, with The blind pavilion, and, later that year, he installed The weather project at Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall in London.

Elíasson's other projects include The New York City Waterfalls, installed on Manhattan and Brooklyn shorelines during summer 2008 and Your rainbow panorama, a 150-metre circular, coloured-glass walkway situated on top of the ARoS Museum in Aarhus, Denmark, 2011.

Elíasson lives and works in Copenhagen and Berlin.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Art can change society by proposing spaces and approaches that encourage new ways of relating to the world, where actions and consequences matter. It prompts us to re-evaluate our value systems, asking us how we measure ourselves and our surroundings. It embraces friction and difference, offering one of the few places in society where differences of opinion are not only accepted but actively encouraged, where we can come together to experience something and be united through disagreement about the significance of that experience. I

“The hut series”, 2012; 56 C-prints; details.

-

Turf houses became the rural Icelandic vernacular for over a thousand years after the techniques of building with soil, wood and uncut stone were introduced by the Vikings in AD 870. These earthy dwellings represent an architecture of necessity providing excellent insulation against the hostile climate and a structural solution to the lack of wood and other construction materials available on the island.

As cute and cosy as they might appear, the torfbæir were damp, dark, rodent-ridden and required rebuilding every 20 to 30 years on account of their organic structure (which also explains why so few remain today). Life was tough for ordinary people in Iceland, especially those who did not own land, and many lived under a serf system called the vistarband right up until the end of the nineteenth century.

Turf houses represent a truly indigenous typology to the island and their influence on contemporary Icelandic architecture is still strong – as seen in current tendencies for environmentally-friendly buildings to dig into or incorporate the surrounding landscape, using forms and features that often hark directly back to these humble mounds. p (gk)

The Keldur turf house in Rangárvellir is thought to be the oldest example of a farmhouse built in this manner in Iceland. There is evidence of a building on this site since the twelfth century, although the earliest parts of the current wooden interior hail from the early 1800s. (Photos: Guðmundur Ingólfsson)

Home Turf

Turf houses became the rural Icelandic vernacular for over a thousand years after the techniques of building with soil, wood and uncut stone were introduced by the Vikings in AD 870. These earthy dwellings represent an architecture of necessity providing excellent insulation against the hostile climate and a structural solution to the lack of wood and other construction materials available on the island...

Image: Engraving of a fisherman’s house near Reykjavík by French explorer Paul Gaimard, 1835.

-

Tin Skins

For one immigrant gone totally native, look no further than the texture of many of Iceland’s buildings. The corrugated iron that covers so many roofs and façades first arrived in the holds of British boats in the 1860s as a cheap, lightweight and stackable commodity, readily tradeable as robust sheet roofing in return for Icelandic sheep. But in a country lacking a good supply of timber, the corrugated iron sheeting soon became the default wall-cladding for buildings as well, found to provide a sturdy and long-lasting rain-shield once its own protective galvanising was supplemented by zinc-based paint to prevent corrosion – hence the explosion of colour seen today across the Reykjavík cityscape. p (rgw)

Photo: Fiona Shipwright

-

![]()

Focus on post-independence housesby George Kafka

Iceland’s independence from Denmark in 1944 coincided with new impulses in the island’s architecture. This developed into a regional modernism that incorporated local techniques of building with the landscape, combined with the international language of modernism that the island’s architects brought back from their studies abroad. Here are four domestic projects, reflecting this evolution of vernacular and functional elements towards a new Icelandic architecture.

-

SÓLHEIMAR 5

1957, Gunnar Hansson

—

In the 1950s, influenced by modernist theories of urbanism, new residential suburbs sprawled rapidly out from the centre of Reykjavík.

Heimar, one such neighbourhood, was designed by Gunnar Hansson in 1955 and contained Iceland’s first high-rise housing block, alongside terraced housing and this, a single family house which exhibits the clear influence of Le Corbusier with its white concrete façade and prominent pilotis. Hansson, rather than adapting the sloping site to create a tabula rasa, designed the house’s form to respond to the topography with a stepped ground floor. The interior is split over three levels, with a top floor living room that receives generous sunlight through large windows. Today the house remains in its original form, having survived both the climate and the wrecking ball that did for so many of its modernist peers.

![]()

Previous page: PK Arkitektar's Árborg House. (Photo: Rafael Pinho and Helge Garke) This page: photos by Guðmundur Ingólfsson.

-

BAKKAFLÖT 1

1965-8, Högna Sigurdardottir

—

Like many of her contemporaries, Högna Sigurdardottir (born 1929) studied architecture abroad before returning to practice in her native Iceland. She was the first Icelander to study at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the first woman to design a building in Iceland and perhaps one of the most underappreciated architects of her era. The interior of her extraordinary Bakkaflöt 1 house (1965-8) in Garðabær on the outskirts of Reykjavík, reflects this international influence and has many of the features of European mid-century modernism: an open plan living space, use of exposed concrete in the interiors and large floor-to-ceiling windows.

From the outside, however, the house appears more uniquely Icelandic in its use of steep, grassy berms which cover much of the façade, protecting the house from the island’s notorious winds and harking back to the nation’s original domestic structure: the turf house.

![]()

Photos: Guðmundur Ingólfsson

-

H71A

2001/2012, Studio Granda

—

The close-knit nature of Reykjavík’s creative community means collaboration is a vital part of the islanders’ mentality. This studio, converted from a house in 2001, is the product of years of collaboration between architects Studio Granda and Sigurgeir Sigurjónsson, the practice’s regular photographer and occasional construction worker. Over a decade after the initial conversion, the studio has recently been extended to include a garage, roof terrace and gallery space.

The architecture itself is typical of Studio Granda in its tastefully restrained approach to materials and design. With its corrugated iron cladding, the building’s exterior blends seamlessly into the texture of Reykjavík’s existing streetscape. Inside, the basalt tones of the board-form concrete walls recall the volcanic hues of Reykjavík landmarks such as Guðjón Samúelsson’s National Theatre. Here is a case of referencing the environment, both built and natural.

![]()

Photos: Sigurgeir Sigurjónsson

-

ÁRBORG HOUSE

2010, PK Arkitektar

—

This private vacation house two hours east of Reykjavík is a good example of high-end living on the island – for those that can afford it. Its builders were so conscious of its rural context that moss displaced during construction was preserved and “regularly nursed” before being returned to its natural habitat …on the roof of the house. Gravel sourced from a nearby river is also incorporated into the scheme, providing the broken pebble-dash effect in the corrugations of the house’s concrete exterior walls.

With sparse interior furnishings, the floor to ceiling windows at the back of the house throw the emphasis onto the unrestricted views over the vast surrounding valleys, which can also be enjoyed from the built-in reflecting pool – decorated with selected pebbles from a nearby riverbed. Naturally. I

![]()

Photos: Rafael Pinho and Helge Garke

-

In 1890, William Morris, the English artist, designer and social activist published News from Nowhere (or an Epoch of Rest), a utopian work of fiction imagining a world with no money, no class system, no marriage, no big cities and a society in which the beauty of nature is not only prized but also embodied in its architecture.

Whilst the book is set in London, glancing down that list of attributes one can’t help but wonder if Morris secretly intended it to be set in Iceland. Blazing a trail for the legions of tourists who have since fled to the same wilderness by hopping on a low-budget flight, Morris visited twice in 1871 and 1873, taking a train from St Pancras to Newcastle, then a ship from Berwick in Scotland, sailing past the Faroes and arriving into Reykjavík some eight days later. Once on the island, he travelled, largely on horseback, throughout Vesturland (the Western Region, as depicted in this map), describing the mountains he saw as “looking as though they had been built and half-ruined”.

He kept a journal of his first trip, which, perhaps because it coincided with an unhappy period in his home life (his wife Jane’s increasingly close relationship with the pre-Raphaelite artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti), does not contain any visionary theory, but is rather a straight travel diary. In it he details many experiences familiar to the contemporary tourist including his frustrations with his companions, Icelandic interpreter Eirikr Magnusson (“He was so late that I began to get fidgety”) and his good friend, Charles Faulkner (“To say the truth, Faulkner has no genius for cookery”). A must-read for who might also venture to the place he described as the “most romantic of all deserts”. I (fs)

Notes from Nowhere

In 1890, William Morris, the English artist, designer and social activist published News from Nowhere (or an Epoch of Rest), a utopian work of fiction imagining a world with no money, no class system, no marriage, no big cities and a society in which the beauty of nature is not only prized but also embodied in its architecture. Whilst the book is set in London, glancing down that list of attributes one can’t help but wonder if Morris secretly intended it to be set in Iceland...

-

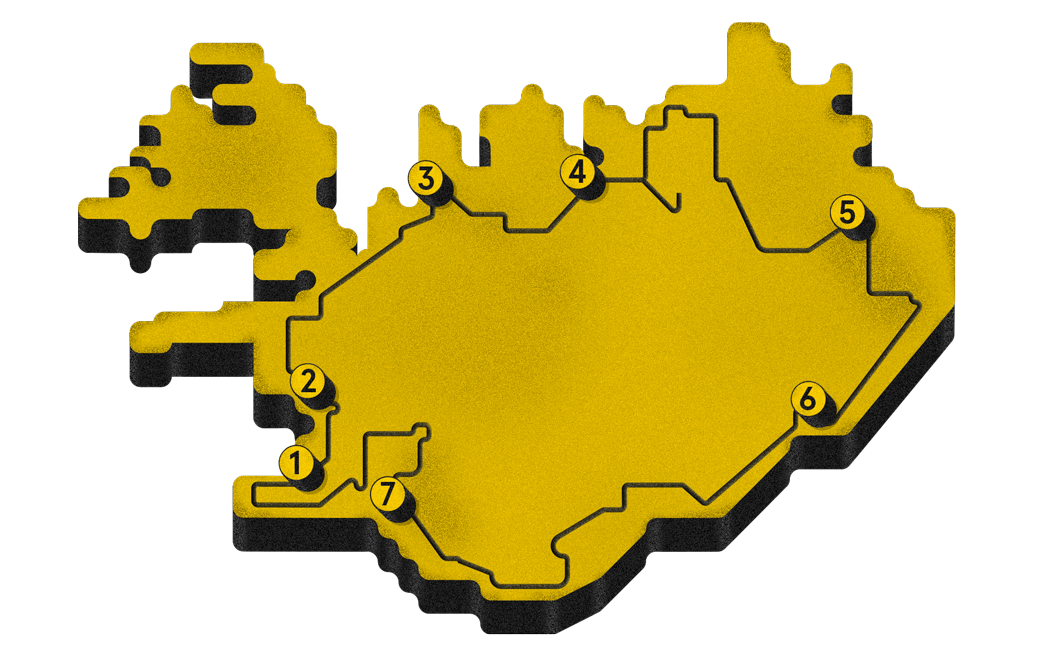

![]()

The Road

Less TravelledRoute 1/Hringvegur

Date: 1974

Client: The Icelandic Road and

Coastal Administration (IRCA)d -

It says something about the contemporary visitor-pulling power of Iceland that a piece of infrastructure meant to take you to destinations has become a destination itself. However, considering the awe-inspiring landscape that Iceland’s national ring road (the Hringvegur or Route 1) tours through, it’s not hard to see why. Travelling the 1,340 kilometres of Route 1 has to be one of the world’s ultimate road trips.

But scenic beauty can be deceptive. Anyone expecting a smooth ride will encounter some bumpy interruptions, as some sections are still lined with the finest Icelandic gravel as opposed to asphalt. Additional hazards can include deadly winds, blizzards, ice, earthquakes, floods and – if you are really unlucky – volcanic eruptions. At least one point along the length of the road is usually closed for some reason or other, especially in winter. The 880m bridge crossing the Skeiðará river, for example, was the last piece of this orbital puzzle when it was completed in 1974, but in 1996 it was partially destroyed by a glacier run (a chunk of the original bridge still lies embedded in the ground beside its successor, a sober reminder to anyone who might dare think human engineering can outdo the power of nature here).

Previous page: photo by Fiona Shipwright. This page: Flickr/Chris Goldberg. (CC BY-NC 2.0)

-

A glance at the map of the Hringvegur is also a good way of reminding (or teaching) visitors that Reykjavík (1) is not the only place in Iceland. Stops along the way include Borgarnes (2), a historical centre and one of country’s first settlements; Blönduós (3), home to one of the country’s many distinctive churches, designed by Dr. Maggi Jónsson; Akureyri (4), Iceland’s second city, located just under the Arctic Circle; Egilsstaðir (5) a young township, est. 1947, whose 1970s church designed by Hilmar Ólafsson has fine acoustics; Höfn (6), host of an annual Humarhátíð (lobster) festival; and Selfoss (7) home of the rather nice Suðurland college building, also by Maggi Jónsson.

Typically though, most tourists tend to stick to a far smaller ring cycle, bussing around the route of the 300 kilometre Golden Circle in South Iceland, which takes in Þingvellir National Park, The Great Geysir, the even greater Gullfoss waterfall and gift shops of almost equal dimensions. But this is probably a blessing since the reason many visitors travel Route 1 is to relish the blessed isolation in what is still one of the emptiest and wildest places in Europe. p (fs)

![]()

Illustration: Janar Siniloo

-

Einar Thorsteinn (1945-2015) was an experimental architect of singular vision. Born in Iceland, he studied in Hanover and Stuttgart, Germany and worked in Frei Otto’s architecture studio from 1969 to 1972, where he was part of the team designing the lightweight roofs structures at the Munich Olympic Village. Back in Iceland from 1972, Thorsteinn founded his own firm, the Constructions Lab, which produced a number of lightweight structures from ceremonial event tents to geodesic domes for geothermal power plants. His innovative work with spatial geometry also led him to collaborations with the likes of Buckminster Fuller and Linus Pauling.

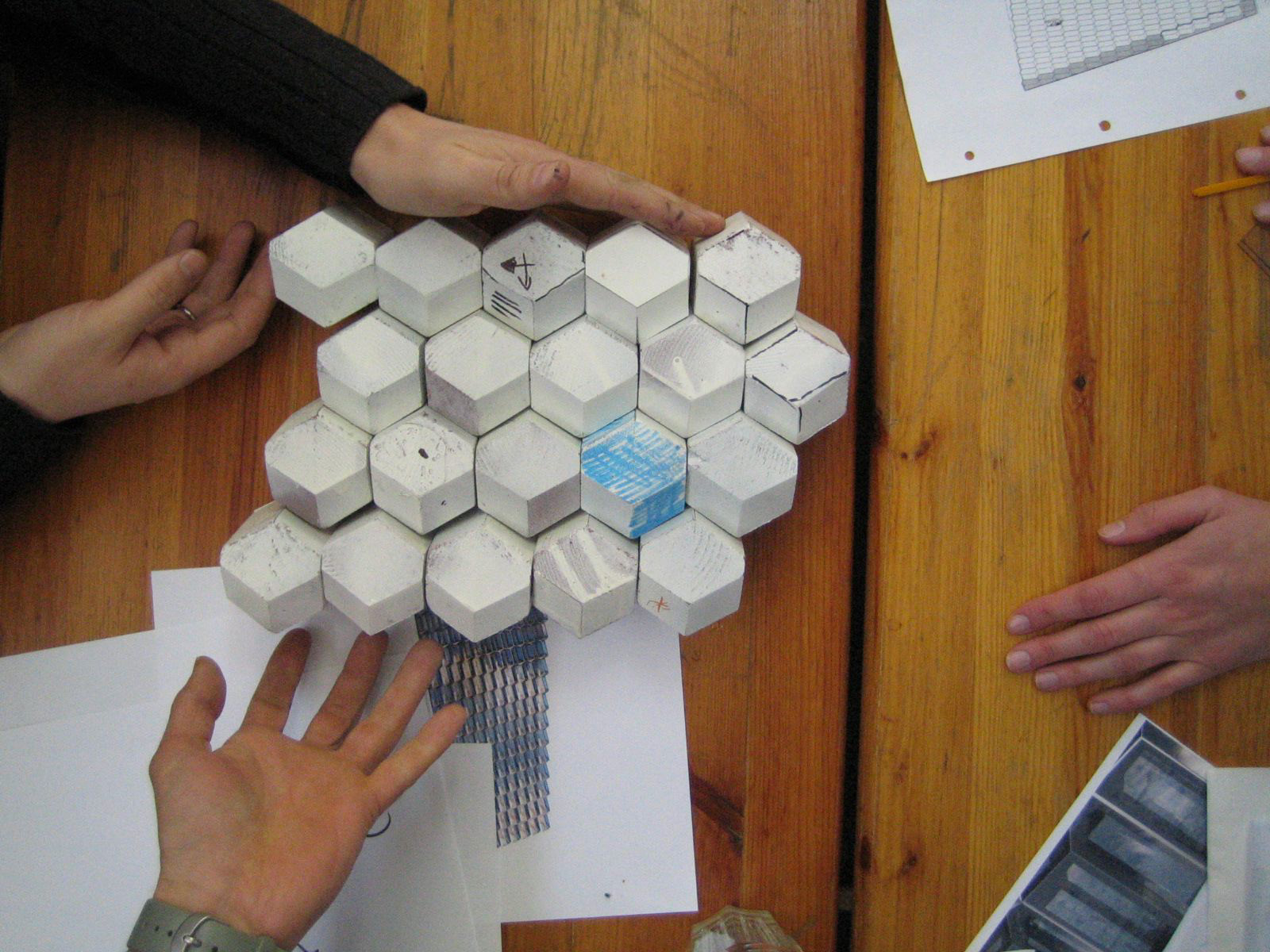

This picture shows Thorsteinn at work in the studio of Ólafur Elíasson in Berlin where he worked in-house from 2000 to 2013, advising and calculating many of the complex polyhedral volumes and spatial challenges that are integral to Elíasson’s work – most notably the five-fold symmetry of the “quasi brick” polyhedron façade of the Harpa Concert Hall and Conference Centre. “In his many years at the studio”, says Ólafur Elíasson, “Einar gave shape to space – and he also gave space dimensions that go beyond mathematical definitions”. I (sl)

Giving Shape to Space

Einar Thorsteinn (1945-2015) was an experimental architect of singular vision. Born in Iceland, he studied in Hanover and Stuttgart, Germany and worked in Frei Otto’s architecture studio from 1969 to 1972, where he was part of the team designing the lightweight roof structures at the Munich Olympic Village. Back in Iceland from 1972, Thorsteinn founded his own firm, the Constructions Lab, which produced a number of lightweight structures from ceremonial event tents to geodesic domes for geothermal power plants. His innovative work with spatial geometry also led him to collaborations with the likes of Buckminster Fuller and Linus Pauling...

Photo courtesy Ólafur Elíasson.

-

The Harp that Sang

The saga of Reykjavík’s Harpa Concert HallBy Sophie Lovell & Fiona Shipwright

-

Reykjavík’s giant Harpa Concert Hall and Conference Centre has courted controversy both before and since the 2008 financial crash. It has been decried as a pivotal cause of all woes in one breath and celebrated as the city’s saviour in another. Now that the dust and the stock markets have settled somewhat, how is this building faring, in the face of mercurial Nordic coastal weather conditions and public opinion?

Previous page: detail of the Harpa’s polyhedral façade design. This page: south façade of the Harpa Concert Hall and Conference Centre. (All images courtesy Ólafur Elíasson, unless otherwise stated)

-

Right from the start, the Harpa project was a very grand plan for such a small place. Why did the most northerly capital in the world and its 120,000 residents need a vast 28,000 square metre concert hall complex? In the pre-crash era, when the Bilbao Effect was still a bit of a thing, it perhaps wasn’t so much because Reykjavik needed to build such a showstopper, more that, with so much banking money washing around pre-crash, it felt that it could.

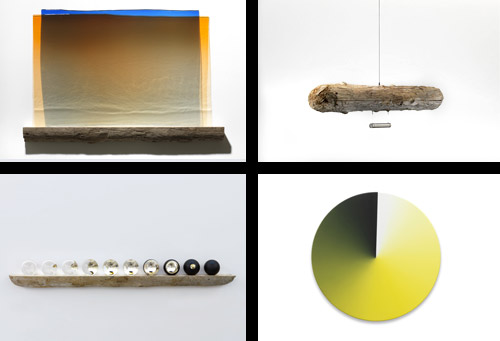

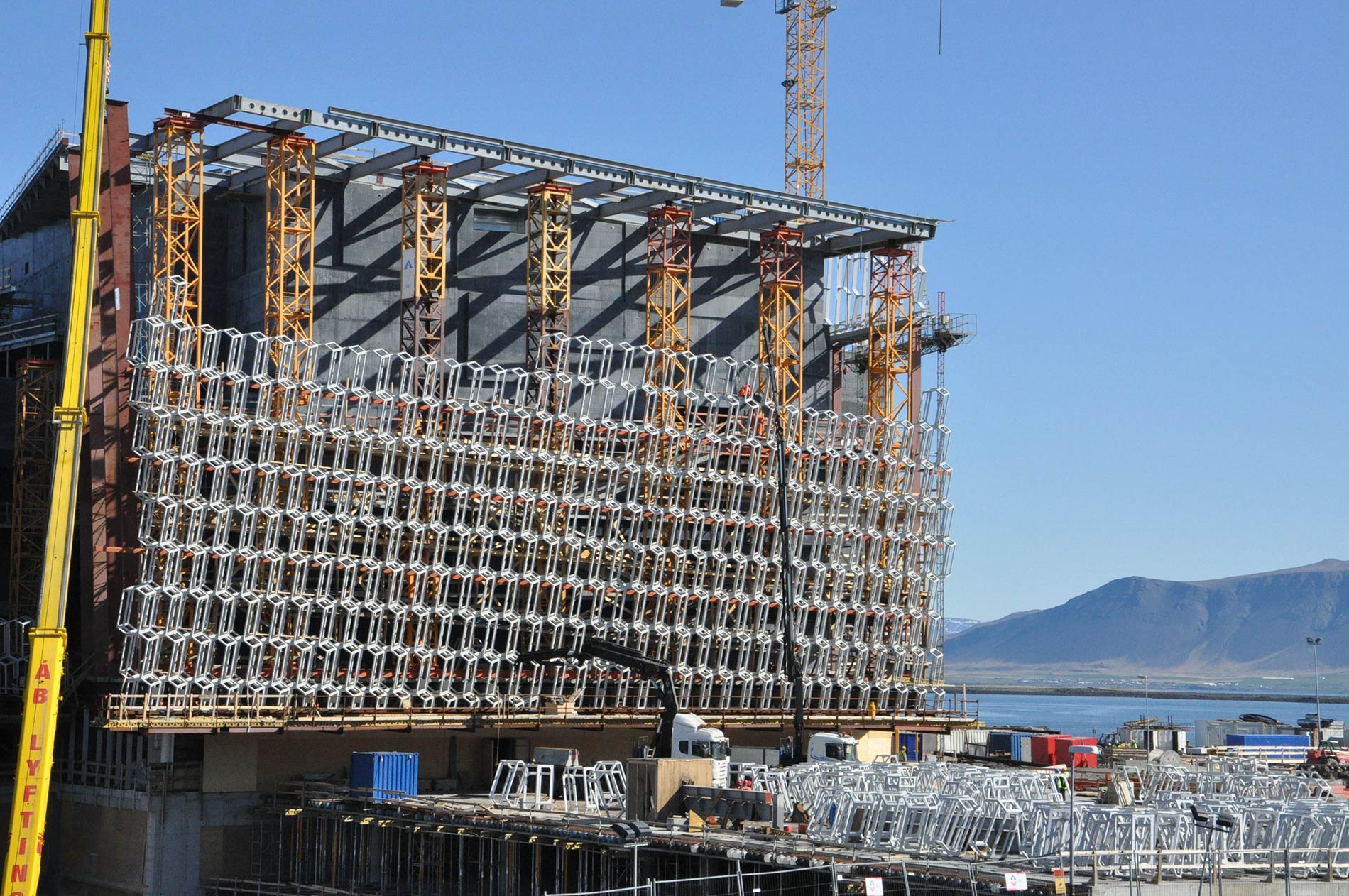

So the dream took flight in the form of a PPP (Public Private Partnership) competition launched in 2004, seeking designs for both the hall and the redevelopment of a prime site by Reykjavik’s harbour on the north western edge of the old city centre. The winning design came from Portus Group, a team that comprised Danish firm Henning Larsen Architects, Icelandic practice Batteríið Architects and the Danish-Icelandic artist Ólafur Elíasson – the latter coming up with what was to become the building’s distinctive polyhedral façade. From without the building looks rather like two massively angular conjoined rocks that have come to rest by the harbour. From within, the enormous light-filled atrium foyer, which connects eight floors, affords visitors magnificent views out to sea, to the Esja mountain and back across the city. The architecture and context are striking, but it is the façade that draws the attention. Its mesh of interlocking crystalline units is glazed in iridescent glass filled with rainbow colours. They also have light elements built in which make the building shiver and glow in ever-changing patterns. Elíasson intended his facade not just as a skin, but as “an integrated part of the building”. Its stackable “quasi brick” modules are based upon five-fold-symmetry, inspired by the crystallised basalt columns found throughout the country and developed by the late Einar Thorsteinn, an Icelandic architect and Elíasson’s close collaborator in the latter’s Berlin studio.Back in 2004, the concert hall’s prime harbour front plot had been earmarked as the place where the country could finally make good on its longstanding promise to build a venue for Iceland’s musical heritage. The pedigree of that history, which stretches from centuries-old folk songs to the pop superstar success of Björk, Sigur Ros, Múm et al, had already instigated an influx of visitors to the country, attracted by “coolness” in every sense of the word. Construction began in 2007, only to be abruptly halted in in 2008 when the island’s finances froze and the private funding collapsed.

There then followed a great deal of soul-searching and “clever financing” in an attempt by the city to save what was supposed to be its pride and joy from becoming an orphaned and abandoned embarrassment. It was the state/municipally owned East Harbour Project (EHP) in the end that adopted the Harpa and brought it in from the cold. Where private financing failed, the state, and therefore the people, had to step in. Work was resumed work in May 2009 and the building was eventually completed in 2011.

-

![]()

Testing the five-fold-symmetry of the façade’s “quasi brick” modules.

![]() The building’s distinctive polyhedral façade in mid-construction.

The building’s distinctive polyhedral façade in mid-construction. -

During that same period, Iceland lost many financial friends in the EU, but when it came to architecture, the view was apparently more positive. Harpa was awarded the EU’s Mies van der Rohe Prize in 2013, the jury of which noted “with satisfaction” that it had “captured the myth of a nation – Iceland – that has consciously acted in favour of a hybrid-cultural building during the middle of the ongoing Great Recession.”

However it was precisely this “favour” for the construction of such a giant concert hall between 2008 and 2011, that some Icelanders objected to – it seeming to be the country’s only visible construction project at the time. For in the aftermath of the crash some argued that it would have been better to add Harpa to the catalogue of the island’s unrealised architectural dreams, leaving the half-finished shell on the plot as a ruin-porn reminder of the financial cataclysm wrought there.

Eldborg (“Fire Mountain”), the largest concert hall at Harpa. (Image courtesy Harpa)

-

But realistically, with Reykjavik’s capital-of-cool-syndrome looking like one of the only viable cash-rich lifelines, the cost in terms of reputational damage to the country might have been greater than the financial means needed to finish the project.

The Harpa has four concert halls, each representing one of the four elements of nature: earth, wind, water and fire. The largest, Eldborg (meaning “fire mountain”), is intended to mimic a red-hot rock core and can seat an audience of 1,800. Like its smaller counterparts, its acoustics were designed by Artec Consultants and each can be “tuned” according to the particular music it is hosting. The hall began to resonate “officially”on May 4, 2011 with a concert performed by the Icelandic Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Vladimir Ashkenazy, the Russian-born pianist who moved to the county in 1968 following his emigration from the USSR.

![]()

Section view of the Harpa. (Illustration courtesy Henning Larsen Architects)

-

»Where private financing failed, the state, and therefore the people, had to step in.«

-

Harpa Reykjavík Concert Hall and Conference Centre, 2005-2011

Architects: Henning Larsen Architects and Batteríi∂ Architects.

Façade design and development: Ólafur Elíasson and Studio Ólafur Elíasson in collaboration with Henning Larsen Architects.

Eignarhaldsfélagi∂ Portus Ltd., Reykjavik, Iceland.

A long-term resident of the island, he established the influential Reykjavík Arts Festival in 1970 and has held Icelandic citizenship since 1972.

Since then, the audiences from home and abroad have continued to make a trip to the “harp” by the harbour. Whilst Icelandic music occupies a special place in the hearts of contemporary music journalists, not for Harpa the obscure elitism they have a tendency to champion. The tuning capability of the halls proves its worth in this regard. The electronic/alternative Iceland Airwaves festival remains a yearly fixture on the Harpa calendar but the main programme is dominated by more mainstream crowd-pleasers such as Carmen, Stomp, and a Led Zeppelin tribute band (the real one having played Ashkenazy’s 1970 festival).

Whilst this might grate upon some of Reykjavik’s younger residents, they should probably be applauding this popular music programme encouraged by the current director Halldór Guðmundsson, given that without them they will likely end up paying for the building beyond the predicted 2046, and well into their old age.

Particularly in architecture and city planning, big dreams always tend to be tempered by compromise. But, as Guðmundsson assured uncube, in this case “the one thing which is not a compromise is the building itself” and, having welcomed 1.5 millions visitors through the door last year he is optimistic about the future fortunes of the building. With an almost new building in good shape and functioning well, the signs look very promising that the Harpa will turn out to be a golden harp for the city after all, but as the locals know from centuries of experience, the fortunes of this beautiful island can be as fickle as the weather and nothing here can ever be taken for granted. I

Previous page: Reykjavík Harbour through the Harpa’s glass façade.

-

The story of life on Iceland has always been one of boom and bust, dearth and glut. Back in 1917 a herring-salting factory opened in Djùpavík in the remote Westfjords. By 1919 it was bankrupt. In 1934 it was boom time again and a bigger herring factory was built – the largest concrete building in the country at the time. Alongside the factory, three giant circular tanks were constructed, capable of holding up to 5,600 tons of herring oil. The oil was prevented from solidifying in the winter by metal pipes coiled around their floors funnelling geothermally-heated steam.

But by the mid 40s the herring were (you guessed it) gone and the factory closed in 1954 with the settlement left abandoned until the 80s and the conversion of one of the buildings into a hotel for hardy hikers. These days it the post-industrial landscape rather than the sea that lures visitors, with the old factory now “ruin porn” for tourists, and also a sometime venue for the occasional music performance: thanks to the great acoustics in the tanks, bands such as Sigur Rós have played impromptu gigs in their cavernous bellies. I (sl)

In the Round

The story of life on Iceland has always been one of boom and bust, dearth and glut. Back in 1917 a herring-salting factory opened in Djùpavík in the remote Westfjords. By 1919 it was bankrupt. In 1934 it was boom time again and a bigger herring factory was built – the largest concrete building in the country at the time. Alongside the factory, three giant circular tanks were constructed, capable of holding up to 5,600 tons of herring oil. The oil was prevented from solidifying in the winter by metal pipes coiled around their floors funnelling geothermally-heated steam...

Photo: Guðmundur Ingólfsson

-

![]()

Some Like It Hot

Blue Lagoon Spa and ClinicDate: 1998-2007

Architect: Basalt ArkitektarClient: Blue Lagoon Ltd

-

While there is a long tradition in Iceland of bathing in the geothermally heated water – with records of hot pools back dating from the thirteenth century – this project is the one that joined up the dots in terms of reinventing this experience for the twenty-first century. It combines the uniqueness of sitting in steaming water in the open air and all weathers, surrounded by an extraterrestrial-looking lava landscape, with full spa, wellness clinic and hospitality facilities – intensifying further the extreme nature/nurture juxtaposition.

Natural as it looks, the lagoon here is in fact completely manmade and its piping hot water, drawn up from 200 metres below ground, is the byproduct of a nearby geothermal power plant. The spa, designed by Sigríður Sigþórsdóttir of VA Architecture, was opened in 1998. Its 5,000 cubic metre lagoon is cradled in a rugged lava field, which also cleverly utilises the natural bowl formation of the landscape, protecting bathers from the sometimes bitter winds, whilst its water – an ethereal, milky blue from the combination of minerals it contains – renews itself every 40 hours.![]()

Previous page: image courtesy Blue Lagoon Ltd. This page: photos courtesy Basalt Arkitektar.

-

Basalt arkitektar is an architecture office established in Reykjavik, Iceland, in 2009, committed to the “artistic and poetic dimension of architecture” in their work, with sustainability as an important keystone of their design philosophy. Their work includes projects in the past, such as the different phases of the Blue Lagoon Spa and Hofsós swimming pool, each nominated for a Mies van der Rohe Award, in 2000 and 2010 respectively.

The lava wall which edges the lagoon is incorporated into the design of the spa’s buildings as well, flowing around and through it. The onsite clinic, which opened in 2005, is more orthogonal in shape, with its public rooms lifted above the service areas to maximise light. But with many of its surfaces faced in slices of natural lava, it still continues the idea of the manmade in balance with nature in its interiors.

Conveniently situated midway between Rekjavík and Keflavík International Airport, the Blue Lagoon has quickly become one of the top tourist destinations in the country, with many visitors dropping in less for a relaxing spa session than a quick in/out, selfie-recorded dip before flying out of the country.

However, plans are afoot to slow things down a bit and expand the Blue Lagoon’s offer to make it more of a holiday destination in its own right. The lagoon is due to be increased in size by a half from January 2016, and a new 60-room hotel meeting and conference room, and roof-top restaurant designed by Sigþórsdóttir, now at Basalt Architecture, is due to open in 2017. p (rgw)![]()

Photo courtesy Basalt Arkitektar.

-

FURTHER READING

Blog Lens18 Feb 2015

Creatures From The Vault

Icelandic designer Brynjar Sigudarson

Blog Building of the Week26 Dec 2015

Nordic Nexus

A little-known gem in Iceland by Alvar Aalto

Magazine Interview29

In the Twilight Hour

An Interview with Kjetil Trædal Thorsen, Snøhetta

Blog Viewpoint17 Jun 2015

Svalbard Sojourns

A de facto commune in the Arctic Circle

Magazine Found33

Arctic City

Otto experiments with environments

Blog Lens05 Jan 2016

A Critical Eye

Iceland's architecture photographer Gudmundur Ingólfsson

Search our archive! -

ZVI HECKER

Issue No. 41:January 28th 2016

Photo: Gili Merin

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Tradition is a dare for innovation.«

Alvaro Siza

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents

The building’s distinctive polyhedral f

The building’s distinctive polyhedral f