-

Magazine No. 43

Athens

-

No. 43 - Athens

-

page 02

cover

-

page 04

Editorial

Athens

-

page 05 - 08

The Eye of Greece

An introductory view of the city

-

page 09

Syntagma Square 1/6

The September 3, 1843 Revolution

-

page 10 - 17

From the Bottom and the Top

Powering Athens through collectivity and informal initiatives by Cristina Ampatzidou

-

page 18

Syntagma Square 2/6

Syntagma Square metro station

-

page 19 - 24

Nowhere Now Here

A photo essay by Yiorgis Yerolymbos

-

page 25

Syntagma Square 3/6

“Syntagma Square” by Zafos Xagoraris and Aristide Antonas

-

page 26 - 32

Back to the Garden

Athens and opportunities for new urban strategies by Aristide Antonas

-

page 33

Syntagma Square 4/6

“After Dark” by Yiannis Hadjiaslanis

-

page 34 - 41

Point Supreme

An interview by Ellie Stathaki

-

page 42

Syntagama Square 5/6

“Fountain” by Sofia Dona

-

page 43 - 49

Ad Hoc Autonomy

Focus on Athenian maker projects by dpr-barcelona

-

page 50

Syntagma Square 6/6

Solidarity with Refugees

-

page 51 - 55

In the Photo Booth with...

John Pawson

-

page 56

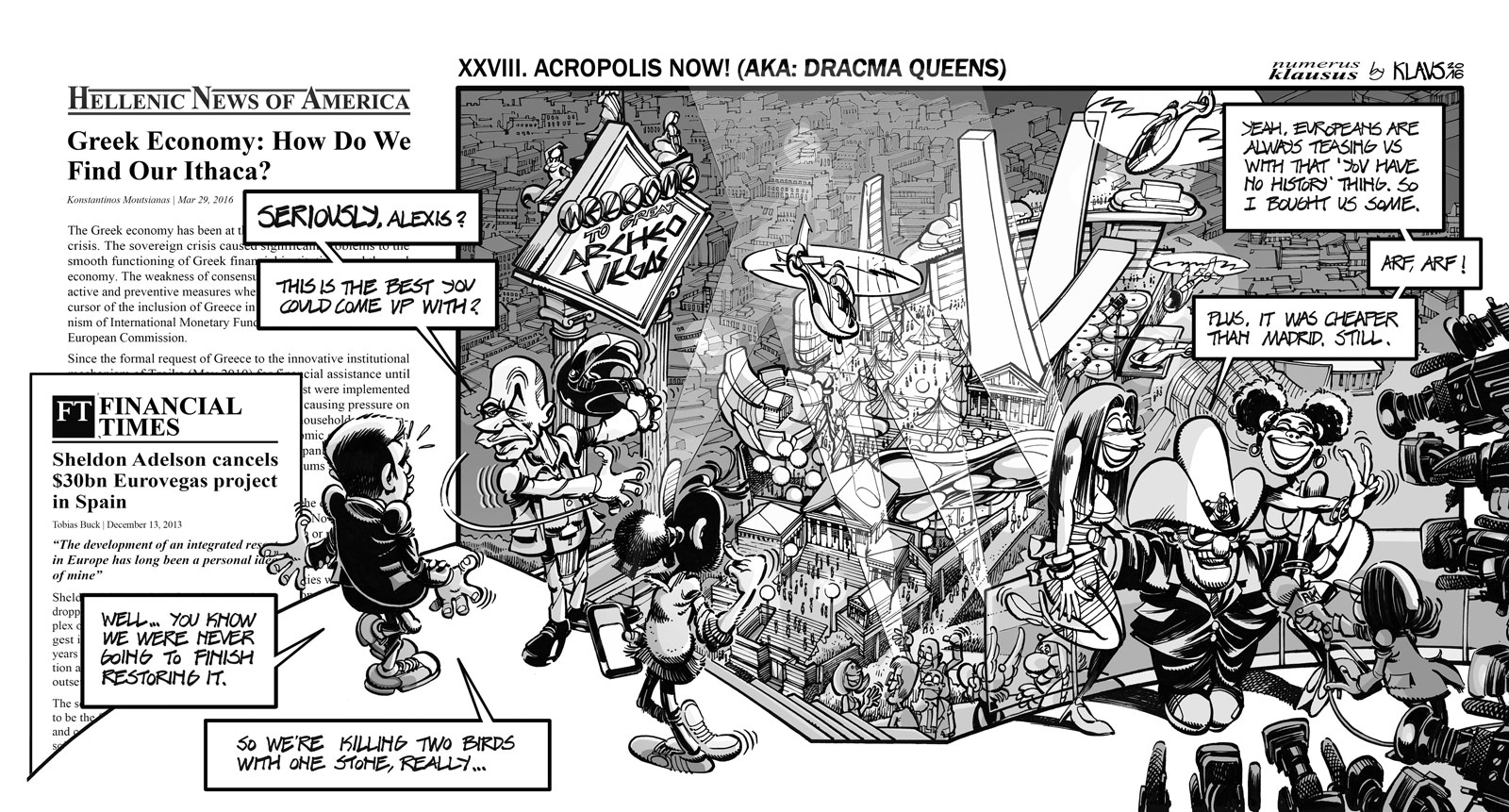

Klaustoon

VVVIII: Acropolis Now! (AKA: Dracma Queens)

-

page 57

Further reading

-

page 58

and beyond...

-

-

uncube's editors are Sophie Lovell (Art Director and Editor-in-Chief), Florian Heilmeyer, Fiona Shipwright and George Kafka; graphic design: Lena Giovanazzi, graphic assistance Janar Siniloo and Diana Portela.

uncube is based in Berlin and is published by BauNetz, Germany's most-read online portal covering architecture in a thoughtful way since 1996.

It is with mixed feelings that we bring you this issue of uncube: sad because we have to tell you that it will be our last – and endings are always sad – yet happy because uncube no. 43: Athens marks the end of a glorious experiment that has shown there is not only a place but a need for viewing architecture within the context of other disciplines and contemporary mores.

And what better subject to end on than a city, which, despite great economic adversity, is forging new paths in informal urbanism – from the bottom up and through the myriad collaborations of the people that live there.

Venerable Athens, the “cradle of Western Civilisation” and birthplace of democracy; as a modern city it has known crisis for so long that it has now become a permanent condition and in response, its ingenious citizens are having to take into their own hands the areas of civic provision that their (democratically elected) governments are failing or unable to provide.

This issue takes space, particularly public space, as a thread to lead us through the dense and complex labyrinth of a city’s strategies to not only survive, but thrive once again as well. So join us one last time as we take you “beyond”, through the streets and squares of Athens.

Cover image: Vishy Moghan

-

![]()

![]()

A view of the city

By Fiona Shipwright & George Kafka

Illustrations by Diana Portela

-

Context has always been our watchword at uncube, so in this introduction to our Athenian issue we haven’t picked out shiny architectural highlights so much as highlighted some sites that set the scene for our particular focus on a contemporary Athens beyond “tragedy” and “crisis”. A place where Athenians are doing it for themselves.

Still going strong at 3,400 years of age, Athens’ story is a marathon tale of struggle and solution. Its recent history alone includes revolution, occupation, economic miracle, military juntas, tourist influx, the Olympics, #occupations and more. The outward-facing side of the city has always co-existed with political upheaval – referendums, dictatorship, internal and external migration, all of which has shaped and reshaped its map. Over the years, large infrastructural projects have attempted to join up the points and reconcile these two sides of the city, providing services to the general population that are enjoyed by visiting tourists. When these fail, it is Athenians themselves who step in to bridge the gaps.

Our little tour shows a city where the built environment manifests its multiple layers of history more clearly than most. So welcome to Athens, let’s go sightseeing… -

Polykatoikia

Throughout Greece

Housing typology

1930s onwardsAlthough the postcard picture of Athens may be the ancient Acropolis, there is perhaps no architecture more symbolic of the modern Greek capital’s development as a city than the polykatoikia. Based on Le Corbusier’s Dom-ino self-build housing concept (which in turn comes from the classical), these mid-rise residential buildings swept – unregulated – across the Attic landscape from the 1930s onwards thanks to high housing demand and their fast, simple construction process. The spread of this polykatoikia typology is largely responsible for the city’s dense, unplanned character. Similarly, the culture of home-ownership in Greece was facilitated by the proliferation of these structures – just before the economic crisis, Greece had home ownership figures over 84 per cent, the second highest rate in Europe at the time. Reluctant to spend on social welfare, the conservative post-war Greek government supported the self-build, home ownership model through relaxed property laws and planning restrictions. I

The Blue Apartment Building

Exarchia

Kyriakoulis Panayiotakos

1933Designed by architect Kiriakoulis Panagiotakos, this local landmark may have lost the vibrancy of its original blue hue but it will be a while before its legend fades. When first built it was an interruption to the city’s fabric both in terms of its colour as well as its form; in 1933 Athens was not yet dense with the multi-storey apartment blocks. This gesamtkunstwerk is now regarded as a flagship example of apartment design of the period (a visiting Le Corbusier described it as “tres beau”), not just for its striking exterior and finely detailed interior, but also for the attention paid to the design of its common spaces, which were intended to facilitate meetings between residents. Echoing this focus on the social, the building’s links with the Greek Left date back to the interwar period: Leonidas Kyrkos (the “father” of today’s SYRIZA party) and the prominent Greek Communist Elias Iliou both lived in the building at one time, and their families continued to do so when both spent time in exile. I

Acropolis Walkway

Acropolis of Athens

Dimitris Pikonis

1957The end of the Greek Civil War (1946-49) saw the rise of a conservative, nationalistic government keen to emphasise traditional aspects of Greek identity. Luckily for them, they had ancient temples on hilltops to play with and so were able to commission architect Dimitris Pikonis to landscape a walkway leading up the Acropolis to the Parthenon. What resulted is a masterpiece of bricolage design, where Pikonis – in collaboration with local craftsmen and his students – organised found fragments of marble and clay into complex geometric patterns and moulded pathways into a precise choreography of screens, building up to a grand reveal upon arrival at the Parthenon. A projection of Greek identity indeed, and one that would pave the way for a new image of the city to be sold to visiting tourists. I

Hilton Athens

City Centre

Emmanuel Vourekas, Prokopis Vasileiadis, Anthony Georgiades & Spyro Staikos

1963Athens’ economy was a snarling tiger in the 1960s when the Greek Economic Miracle generated growth second only to Japan. New buildings were popping up everywhere to house the burgeoning population, industry and commerce.

Whilst Bauhaus master Walter Gropius’ 1961 design for the US embassy made some reference to the Doric columns of the Parthenon, the Hilton Athens’ culturally vague use of the international style better epitomises the era. The new hotel had a lavish opening in 1963 attended by Conrad Hilton himself and it rapidly became a landmark for luxury tourism in Athens. Yet despite its popularity with tourists and Athens’ high-society, the hotel was scorned by architectural purists as cultural “vandalism” for its view-blocking proximity to the Parthenon. IPolytechnic Uprising

National Technical University of Athens

Exarchia

1973On November 14, 1973, a student protest against the ruling military junta of 1967–74 began at the Athens Polytechnic. By November 17, some 24 protestors were dead (source: National Hellenic Research Foundation) after the right-wing military dictatorship sent tanks in to disperse them.

More than forty years on, these events continue to cast a shadow. Every November the streets of Exarchia become a backdrop for the ritual of commemoration, and in recent years, the spectre of the 1973 riots has had ominous parallels with protests in response to draconian austerity measures. I

-

Elliniko District

1938 onwards

Just over 10 kilometres south of the Acropolis is the suburb of Elliniko. It is home to a number Athenian developments, including Hellinikon International Airport (notable for its Eero Saarinen-designed East Terminal building), completed in 1938 and which closed in 2001; Hellinikon Olympic Complex (from the 2004 Olympics), and the still-unrealised Hellenikon Metropolitan Park, proposed to be the world’s “biggest city park” (property developer-speak for: a thousand hotel rooms, luxury apartments, offices, a shopping centre, a marina, and an aquarium). Developments on the “park” went mysteriously quiet in 2014, but more recently the Elliniko district has found a new purpose: providing emergency shelter for refugees who have arrived in Greece as part of the European migration crisis, which reached a new level of urgency in summer 2015. According to Greek government figures, as of March 2016, around 4,120 refugees are living in former airport buildings and Olympic sites at Elliniko. I

Metro Expansion, Line 4

Attiko Metro S.A

Est. completion: 2023Athens is notable for having a metro system with a public art programme that predates its public by a few thousand years: carefully excavated Athenian archaeological finds can be found on display at the Monastiraki (Lines 1 & 3) and Syntagma (Lines 2 & 3) stops. The system itself has its roots in more recent times, electrified since 1904 in the form of Line 1, which remained the city’s singular metro route until Lines 2 and 3 joined the grid in 2000. Construction on a brand new Line 4 is to due begin in 2016, with a proposed 30 stations (and a price tag of 3.3 billion EUR).With a tentative completion date of in 2023, one wonders not only what further historical finds might be discovered, but also what time has in store for the Greek capital in the meantime… I

-

Syntagma Square 1/6

The eruption of popular protest at Syntagma Square in recent years should come as no surprise to those who know their Modern Greek history. Initially named Palace Square, after the royal palace of the Bavarian King Otto (1832-1862), this central plaza in Athens was the site of an uprising by politicians and military officers on September 3, 1843, who protested the King’s autocratic rule and demanded the signing of a democratic constitution. The movement was successful: Otto signed the Greek Constitution of 1844 and the square was renamed Syntagma (constitution), a fitting title for the place where Greek democracy continues to be defined and challenged by its people. I (gk)

“The Revolution of September 3, 1843 in Athens”, H. Martens (1847). Image courtesy The Museum of the City of Athens.

-

![]()

Powering Athens through collectivity and informal initiatives

By Cristina Ampatzidou

-

Since the Greek debt crisis began to unfold in 2009, Athens has become something of an unofficial poster child for informal urbanism. But as Cristina Ampatzidou explains, this Athenian attitude to public space is actually nothing new – and neither, it seems, is the space that exists between the state, the city and its citizens.

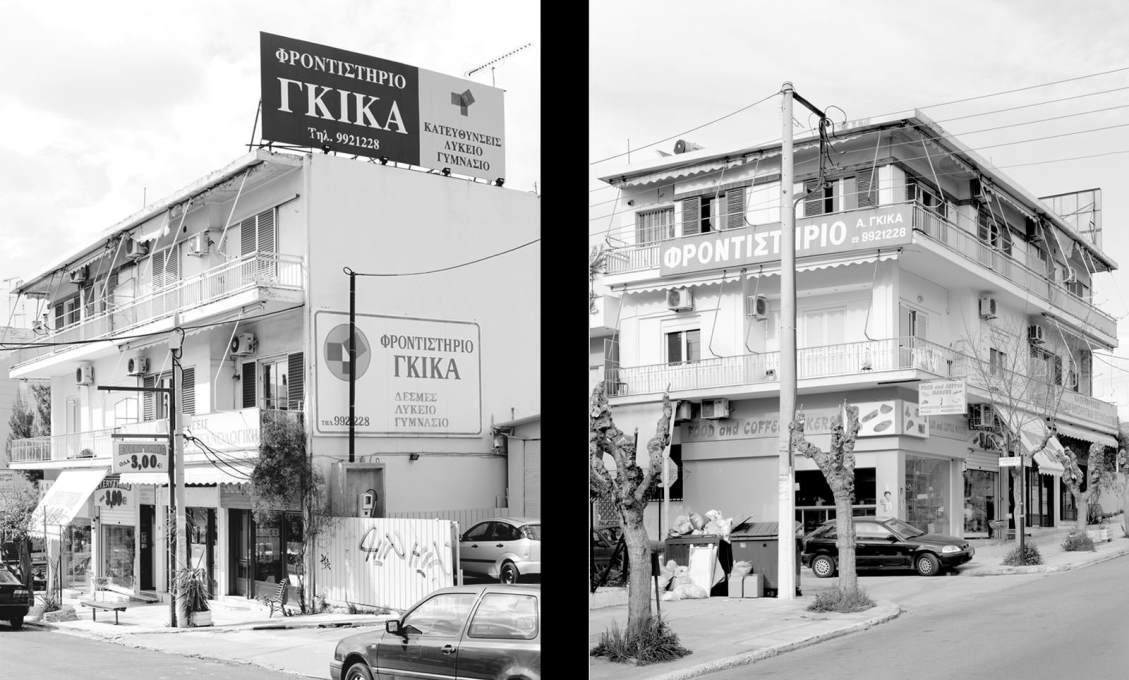

![]()

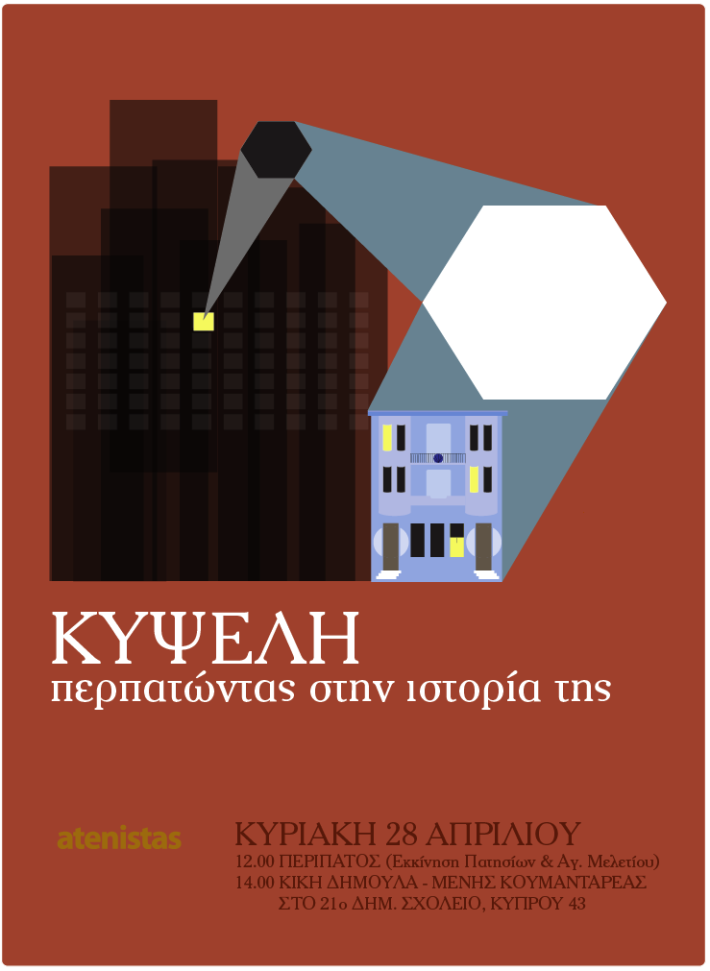

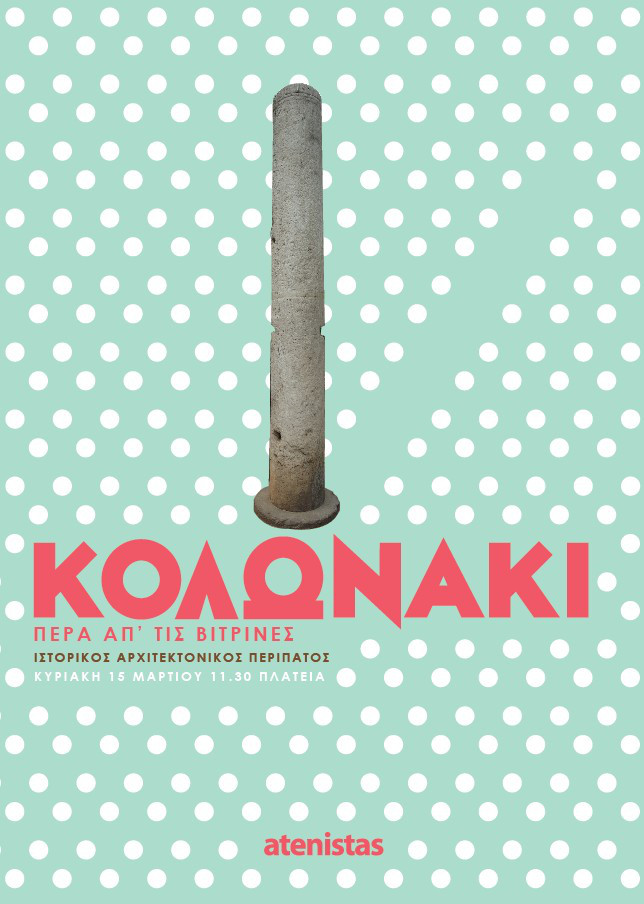

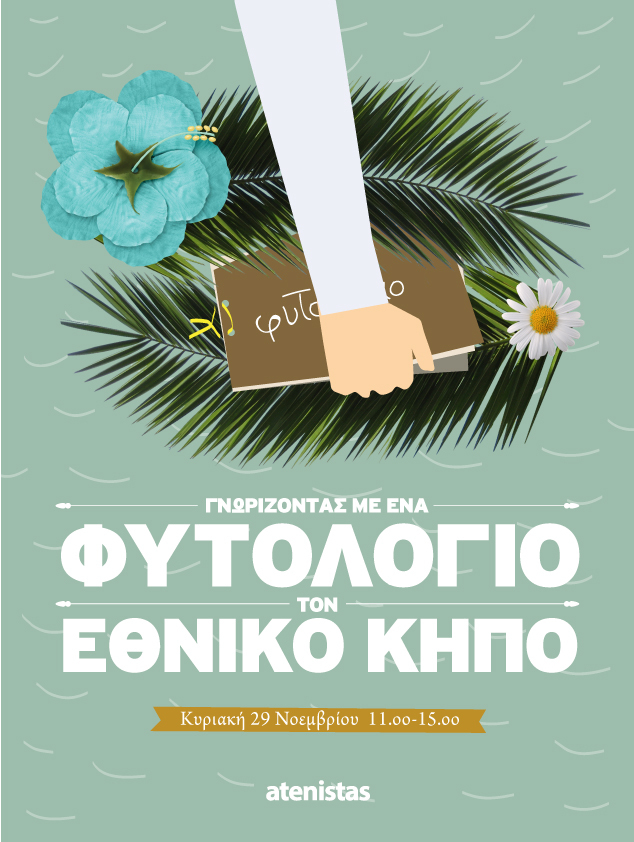

Atenistas are “an open community of citizens” who take an active role in the production of social and cultural spaces in Athens. Their posters, designed by founder Tasos Chalkiopoulos, illustrate the broad variety of projects they undertake.

![]()

![]()

Left: An architectural and cultural tour of Amerikis Square in the Kypseli neighbourhood. Centre: Atenistas’ annual Christmas book, CD and DVD swap in Saint Irene Square. Right: A writing contest with the subject “Streets of Athens”.

-

Athens is a city where the distinction between formal and informal is sometimes very hard to establish. Transcending all scales from the local appropriation of public spaces to the large-scale urbanisation of Greek cities, the production of urban space has developed on a fine balance between state regulations and individual initiatives. Even though this condition is hardly anything new to the Greeks, in light of the ongoing crisis and the impressive response from the bottom, Athens comes increasingly to focus as the newly discovered European capital of informal urban practices.

The failure of the state to prevent the deconstruction of welfare structures has assigned the actions of citizen groups and initiatives a central role in providing many of the social public services, extending from medical services for the uninsured, food and shelter for the homeless, to the maintenance and beautification of public spaces. As the public space is where the image of each city is primarily constituted, it is precisely in this space where the political, economic and social impacts of and responses to the crisis are materialised, forming new dynamic geographies.

![]()

![]()

Left: Book exchange held at Athens’ Municipal Library. Right: A cycling tour of the city, from Gazi to Piraeus port.

-

Grassroots initiatives encompass a spectrum of diverse approaches and ideologies, which makes it impossible to talk about them as a unified phenomenon. Some groups try to achieve broad alliances around their projects, investing time and resources in negotiating with local authorities, inhabitants and shop owners, actively engaging in the activation of local community networks, managing cultural capital and supporting the most vulnerable groups. Initiatives such as the Urban Dig Project that have spent over a year in the Dourgouti neighbourhood bringing together inhabitants, universities and artists, in a series of events and interventions. Operating outside any institutional realm, self-organised social centres, such as Nosotros or Embros Theater organise a range of open cultural activities. Representing different political positions, both these approaches express long term, sustainable and viable paradigms that extend beyond the direct consequences of the crisis.

Nevertheless the majority are groups that act in the short term, as almost activist interventions. Atenistas have collected chewing gum from sidewalks, cleaned abandoned plots of land, and painted and decorated neglected city corners. Proclaiming themselves to be “Athenians in practice”, Atenistas are the local expression of a culture of individuation that attempts to bypass the state and other forms of organised social action and “affirm their share of responsibility in improving the image of their city”.»As the time passes and the crisis deepens, some of these voluntary groups have become an institutional core to which the city turns, seeking steady collaborations.«

-

Such collectivities often claim to assist the state and local administration, either by demonstrating what needs to be done or by substituting them and assuming their responsibilities. This notion of collective initiative and space production puts forward a new idea of citizenship aimed at changing the existing governmental structure indirectly, from within: utilising participation as a new institution that can circumvent established social structures. As time passes and the crisis deepens, some of these voluntary groups have become an institutional core to which the city turns, seeking steady collaborations.

It is also important to notice that despite the attention they receive, such efforts remain mostly individual initiatives supported by limited numbers of people and often fail to instigate larger scale coordination to address actual deficiencies of public space. This accounts both for individuals, who opportunistically support or oppose interventions in the vicinity of their shops or houses when it benefits them, and for the groups themselves that act on their own small scale projects with no ambitions for strategic thinking. This fragmentation also conditions the relation of such initiatives with city authorities. Because of the positive intentions of these interventions, municipalities are compelled to facilitate such groups to carry out projects that contribute to a favourable image of the city. On the other hand, by maintaining the strategic focus and selectively supporting some initiatives over others, the city government influences the reach and longevity of many of these initiatives.![]()

A tour of Athens’ Byzantine monuments by foot. Such tours are designed for Athenians to discover their own city.

-

According to Amalia Zepou, Vice Mayor for Civil Society and Municipality Decentralisation, the relationship between the Municipality of Athens and such groups is not one of dependence but a complementary one, where both citizens and the city administration can work together to increase the quality of life in the city, and where the Municipality takes on a mediatory role instead of that of a sole decision maker. Zepou is the initiator of SynAthina, a platform where citizen initiatives can present themselves, get in contact with the city administration and potential sponsors, and network with each other. For the Municipality of Athens, SynAthina serves a triple purpose: it functions as a source of information about the problems that are top priorities for the citizens, so they are willing to bring forward new solutions and ideas. It is also a platform through which the city can empower initiatives by providing information, permissions and connections to private sponsors. Finally, it is an opportunity for the city administration to modernise its infrastructure by incorporating new technologies and processes developed by these groups or updating its regulations to facilitate further participation of people in their activities.

![]()

A walking tour of the cultural hisotry of the Kypseli neighbourhood, led by residents, writers, directors and architects with close links to the district.

-

However for Platon Issaias, architect and author of the dissertation Beyond the Informal City – Athens and the Possibility of an Urban Common, this entanglement of state and informal practices is hardly an innocent relationship. Spontaneity, informality and voluntarism often act as a smoke screen for a strategy of replacing central planning with a series of managerial tasks, aiming at what appears as an undisputable and unified common good. But, Issaias tells me, there is no single common good; there are things that are good for some people at the expense of others, and stating that a group of people is acting for everybody’s benefit implies a political choice. This is particularly true in the case of a municipality that is subjected to political processes and power relations. In that sense, grassroots initiatives and citizen groups cannot be viewed in isolation from the political positions they represent, openly or not, and we must constantly scrutinise which interests their actions may serve.

![]()

Tour of the Kolonaki area, a neighbourhood rich with interwar period architecture.

-

Cristina Ampatzidou is a researcher and writer with a background in Architecture and Urbanism and editor in-chief of Amateur Cities. Currently pursuing her PhD at the University of Groningen on the topic of gaming and urban complexity, Cristina is also a regular contributor to urbanism and architecture magazines and a collaborator of the Architecture Film Festival of Rotterdam.

cristina-ampatzidou.com

This discourse, of course, does not reduce either the ingenuity of many interventions nor the honesty behind the intentions of the people who offer their time and resources for making their city a better place. However, cities are places full of conflicts and contradictions and each collectivity and each action needs to be positioned separately in this landscape of motivations, actions and political directions. The immediate impact of grassroots organisations on public space in Athens might currently be on the spotlight, but how reliable can they be in the long term? When these actions are filling a gap on account of the lack of public services from existing apparatuses, the nature of the relationship between the state and grassroots initiatives needs to remain a topic of constant negotiation. I

![]()

A childrens’ introduction to the Athens National Garden.

-

Syntagma Square 2/6

The subterranean Syntagma Square metro station is a busy interchange between two metro lines connecting the airport and main commercial and political centre of the city. It also provides connections back through time, to day-to-day life in Ancient Athens. The amphorae, column capitals, walls and drains on display date back to when the area was full of cemeteries and bronze foundries two and a half millennia before. They were unearthed during the excavation of the station, which opened in 2000, part of a new underground network designed to help the city’s drive to improve public infrastructure and cut air pollution from traffic in advance of hosting the 2004 Olympic Games. I (rgw)

Photo: Vishy Moghan

-

![]()

Photography and text by Yiorgis Yerolymbos

-

The African dust arriving from the south covers the city of Athens, once again. Every few years the phenomenon recurs, hiding the city from the face of the earth and leaving behind a sense of uneasiness, as if we have lost our way, our sense of direction.

It so happens that, for long time now, this is exactly how we have been feeling: lost. -

For many years anger has alternated with grief, shame with fear, while the horror of imminent disaster leaves us empty, staring into a void. For quite some time now our lives have been regulated according to financial terminology: recession, inflation, IMF, sustainable economic growth, spreads… Each and every one of us watches events unfold, silently, in front of the TV screen, or loudly, in the streets outside.

Yet there comes a moment when one wonders: how did we come to this? How were we so mistaken in thinking that our future could be better, that our children would have the same opportunities we had and live a better life than their parents? It appears that this is not the case anymore. Obvious as it may seem now, we were caught off guard and life changed on us while we were not paying any attention.

-

Located between east and west, literally as well as metaphorically, we permitted our cities to expand in order to accommodate people coming from all over the country to seek a better future in the capital. Nearly half the population gradually gathered in Athens, forcing the city to spread in all directions. We each created a private home with little regard for public space. We silently accepted illicit construction only because it was deemed “democratic”. We bent the rules, took certain liberties and once the final outcome was there for us to grasp, we remained in awe of how chaotic it really looked.

-

The photographs shown here are from my Athens Nowhere series, which looks at the face of this ancient, and at the same time contemporary, city in an attempt neither to beautify nor to cover any of its shortcomings but to narrate its story as it unfolds. From a critical distance it takes the cityscape for what it really is: the cause of actions and their effect.

-

When uncube approached Greek photographer Yiorgis Yerolymbos about contributing to our issue, he responded by sending not only this quietly arresting series of images‚ Athens Nowhere‚ that present his home city in a state of ambiguity, but also his own reflections, ruminations and regrets on the current situation of his native country and its capital.

Yiorgis Yerolymbos was born in Paris, France in 1973 and studied photography in Athens and Paris and architecture in Thessaloniki. He holds an MA in Image and Communication from Goldsmiths College, University of London (1998) and a PhD in Art and Design from University of Derby (2007). He has presented five solo exhibitions and participated in numerous group shows in Greece and abroad. His work has also appeared in a number of books on art and architecture. Between 2008 and 2001 he taught photography at the School of Architecture, University of Thessaly from 2008 to 2011.

His works include a two-month project in the United States, for which he drove from coast to coast supported by a Fulbright scholarship in 2008. Between 2000 and 2004, he photographed the construction of the Egnatia motorway at its full length of 680km, in Northern Greece. He also worked on the construction of the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center (SNFCC) that includes the New National Library of Greece, the Greek National Opera and the Stavros Niarchos Park in Athens, designed by Renzo Piano.

The cityscapes shrouded in heavy dust presented in the portfolio are portraits of a country under constant stress, facing both financial and moral collapse. At the same time, they represent a return to the basic qualities that make this country what it is, a land that extends hospitality and solidarity to all those in need of a helping hand and a safe refuge. They are my day and night, the reality I experience and the dream I hope for.

They are the country I, too, helped to bring to its knees – and the country I, too, need to rebuild from scratch. This is my country. I intend to stay. ITo see more work from Yiorgis Yerolymbos, see our interview on the uncube blog.

-

“Syntagma Square” by Zafos Xagoraris and Aristide Antonas (c.2000)

Syntagma Square 3/6

With its shortage of space and archaeological layers, Athens is akin to an artwork that is continually being erased and then drawn on top of: its urban spaces etched out over millennia by its populace. A similar kind of back and forth process between artist Zafos Xagoraris and architect/writer Aristide Antonas created this illustration, part of an entry for a competition which reimagined Syntagma Square as an “idiosyncratic void”. Making use of photocopier and correction fluid, it was an intervention by the hand of Xagoraris rather than that of the architect that then brought people into the drawing of the square. I (fs)

-

![]()

![]()

Athens and opportunities for new urban strategiesby Aristide Antonas

![]()

![]()

-

![]()

![]()

Where some might only see decline and decay in the number of derelict buildings in Athens’ city centre, architect and author Aristide Antonas sees an opportunity to encourage the emergence of a new civic character through legislation to support the re-elaboration and redistribution of space – if only the authorities would grasp the nettle.

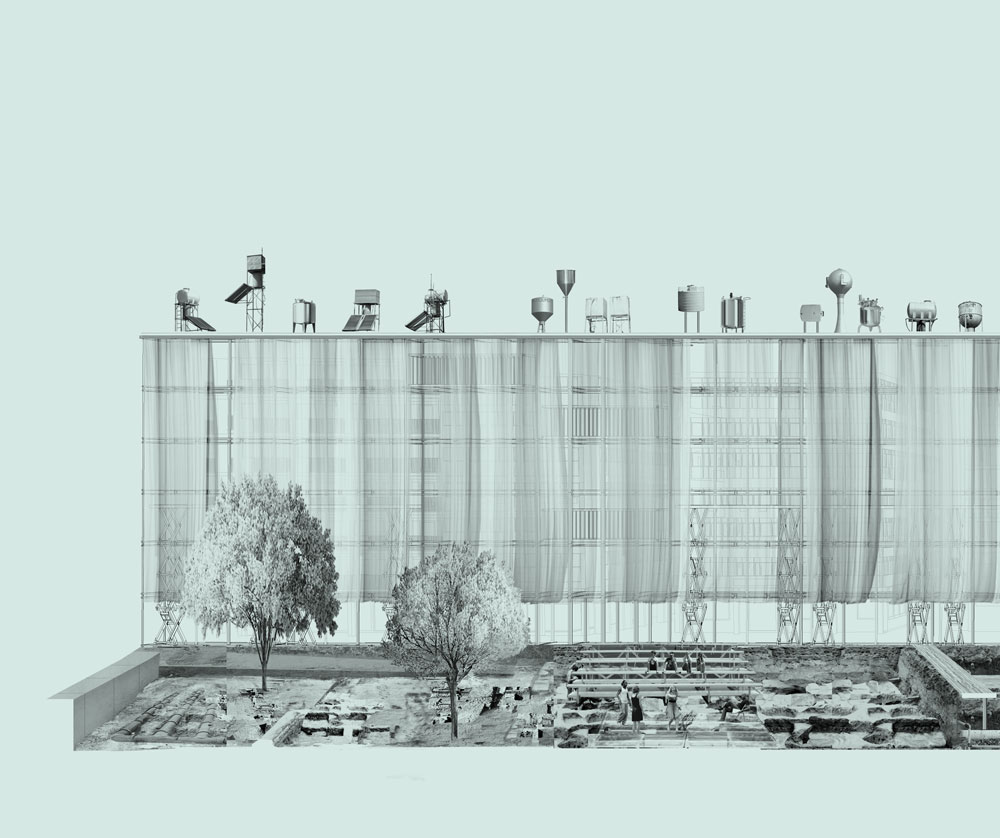

![]()

Previous and current page: Drawing from “Trenches” project by Aristide Antonas. Photos by Zoe Hatyiyannaki: L-R: Former Stock Exchange (1934-2007), Former Social Security Institute, Public Power Corporation S.A.

![]()

-

![]()

The negation of a city and a claim to avoid or reverse the condition of its density is usually organised according to a perspective that leads towards the creation of large urban gardens. A generous empty urban surface is considered to be the necessary condition to avoid the disadvantages of a dense city. This approach (with its emblematic examples in New York, London and Paris) prioritises designed pauses in the urban experience as rhythmical voids that characterise the modern urbs. A framed landscape within the city offers its opposite as a necessary part of the whole, therefore a city includes parks and a percentage of green.

This “negation of the city within the city” also indirectly describes the specific character that is negated with this urban emptying strategy. The question concerning an Athenian negation of the city’s urban fabric would be: what exactly would be negated in the rejection of density in Athens today? In which way would emptiness be contrary to an abandoned centre? Or put differently: what is the meaning of an urban void if it is surrounded by empty buildings? The modern centre of Athens today operates “itself” as the city’s invisible void.In this framework, the perfect negation of today’s Athens would not be a void but a city. Not a pause in the urban experience but a performance, whereas the current urban surface of the centre resembles more the residue after fire.

A “negation of the city” then is not what is missing from Athens. Its centre already seems to be a negation of the city and Athenians are currently seeking to understand and interpret its existing emptiness. The city is unable to institutionalise contents for its vacuum.

The Persian and Hebrew versions of the word “paradise” carry the meaning of “garden”. In some contexts the word refers more specifically to enclosed and secluded gardens, places where the concept of time becomes that of a pause.Referring briefly to Christian tradition, paradise is a place that is either lost or promised. In an analogous way the city park represents a different kind of idealised promise made from the vacuum. It participates in a vision of a temporary cessation of history and is organised as an exit from the community.

![]()

-

![]()

![]()

Athens seeks a new, open, experimental relationship between its existing free space and the various communities that could visit it or inhabit it. A new, different kind of urban culture could begin in these empty spaces of the city centre. The transformation of these empty spaces would then take place as a re-elaboration and redistribution of space or their metamorphosis could serve as mere counterpoint for urbanity. The city has inherited certain facilities that continue to function without conscious relationships towards any common commitment. But Athens now has the chance to examine the possibility of a new civic character arising from the modern ruin that the city centre has become.

![]()

Images from “Weak Monumental Square” project by Aristide Antonas (2015).

-

»Athens now has the chance to examine the possibility of a new civic character arising from the modern ruin that the city centre has become.«

![]()

Sleeping area scenes from “Garden of Athens” project by Aristide Antonas.

-

![]()

Urbanity is becoming differently structured, in a way that is increasingly determined by the performance of the active archive of the internet. A new internet-based civic life is under construction; it takes place upon, and is shaped by, the ruins of the city we once knew.

During our office’s investigations into density and thinking about an alternative “Garden of Athens” that would reflect these digital civics, we proposed a sparse habitation of the existing empty spaces of the city. We orient this scarcity towards a system of hidden interior gardens that should host corresponding installations. In this way, such spaces – not visible from the street – do not simply persist as an abstract vacuum.

Image from “Agglomeration of Empty Shops” project by Aristide Antonas.

-

Aristide Antonas is an architect and writer, currently based in Athens and Berlin. His literature is published at Agra Publications (Athens), JRP-Ringier (Zurich) and Crap is Good Press (Berlin). His theoretical texts are mostly published on the internet. Aristide is principal in the Antonas Office (nominee for a Mies Van der Rohe award, 2009 and for a Iakov Chernikov Prize, 2011). He has been active as a tutor in Greece (NTUA, Athens and UTH, Volos) and as a member of the visiting staff at the Architectural Association, the University of Cyprus, FU Berlin and the Bartlett UCL.

aristideantonas.com

![]()

Our proposal is to facilitate a different idiosyncratic function, determined through the web. We named this new congregation of empty spaces the Sleeping Area, but it is much more than a simple proposal for housing facilities in the midst of a deserted city district.

Instead it is a scheme for an alternative, inhabited, civic garden created through the abolition of walls and the unification of bigger ensembles of spaces, in which the idea of a “garden” is expressed through its influence upon scenography rather than through “natural” elements. The intended result is an “interior park”, open to new forms of functionality for the private and the common sphere in the post internet, Airbnb era; it offers not a pause from urban life, but seeks new urban rules, functioning as a curated elaboration of urban protocols.

The Sleeping Area project could be a realistic proposal if only the state could rethink its legislative powers. It is also a comment on the rationale behind most master plans. The city of Athens is already a reflection of the impotence of master plans when it comes to grasping the dynamics of a changing social sphere. Large-scale projects undertaken in the city since its decline have dealt with the past as if a revitalisation procedure would be possible by stepping back. Another of our proposals (published as the Athenian Trench) for the Onassis Foundation’s Re-think Athens competition in 2013 was not selected by the jury since we proposed implementing changes concerning the function of the city rather than offering a simple street reorganisation and the restoration of facades. At the same time we tried to organise new settings for undetermined spaces, such as the agglomeration of empty shops, or new trenches that would transform parts of important Athenian streets into excavation spaces and ruin gardens.This organisation of urban empty spaces is not a target in itself. A more flexible civic legislation is a possible tool to allow new urban practices to arise in these newly legislated spaces, in parallel to the existing civic code. We would wish this different legislation to have the character of an alternative public democratic use of the web. This use of legislation would then be an architectural tool for an emancipation of the infrastructure. This would offer Athens the possibility of elaborating upon its urban multiple, fragmented interior garden. A new civic content to fill both a material and conceptual blank. I

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

Syntagma Square 4/6

On February 12, 2012, protestors gathered outside Parliament House to oppose the latest round of austerity measures being pushed through by the government. Images of these – at times violent – protests proliferated but photographer Yiannis Hadjiaslanis opted to document their effects in a series called After Dark, shot when the streets and squares had again emptied out and fallen silent: “I set out to record under artificial city light”, he says, “Walking around the historic centre offers the experience of a deserted and battered-down ghost city, a spectre of what it stands for”. I (fs)

Photos: “Athens NNW”, “Mitropoleos” and “Karaiskakis” from the “After Dark” series by Yiannis Hadjiaslanis (2012)

-

![]()

When the world is your oyster why return home to a struggling city?

Interview by Ellie Stathaki

-

Konstantinos Pantazis and Marianna Rentzou met at the Faculty of Architecture at the National Technical University of Athens before going on to study further and work in London, Rotterdam, Brussels and Tokyo. During stints at MVRDV and OMA, the pair started taking on independent work, which led them to form their own architecture practice in 2007; Point Supreme was born. A few months later, they returned to their home country and set up shop in Athens, which has been their base ever since.

Previous page: Interior view of Nadja apartment, 2014. (All images courtesy Point Supreme)

-

Did you feel you were going against the grain, returning to Greece?

Absolutely! It was a bold decision. Of course the crisis had not been felt yet, it was right before it started. It was a bold decision to give up well paid, kind of ideal jobs for a totally uncertain future in a place where not much contemporary architecture was going on. But we felt that there was so much to do there.

Which do you feel was your breakthrough project? What are you currently working on?

It was probably the Aktipis flower shop in Patras and the SixDogs cultural centre in Athens, as both were strong projects made with absolutely no budget, but their success was phenomenal. Currently we are finishing a house in Petralona, a house on a Greek island and a concept for an urban hotel.

Do you prefer certain types of projects? What role does the public realm play in your work?

We prefer projects with an urban impact: public projects rather than private spaces. We want to improve life in the city as a whole; that is why our private projects are being treated in a similar way to public ones. We enjoy working on anything. We have combined expertise at all scales of design, so we treat small projects like cities and urban projects like furniture. We don’t choose our projects, they choose us. We treat public space as a laboratory for fun.

-

![]()

»The challenge is to stay and try to make something out of this mess.«

![]()

Left: Aktipis Flower Shop interior (2008). Right: Garden of SixDogs cultural centre (2010).

-

What informs your core design approach and aesthetic?

We have always been influenced by different ideas, philosophies, agendas and techniques and believe in the power of combinations. So we try to overcome prejudice and to synthesise oppositions. We often work with tight budgets so we have learned to turn problems into advantages.

What are the challenges facing young architecture practices like yours at the moment in Greece?

There is one main challenge; to survive; there is very little work, the whole construction sector has collapsed, plus taxes for the self-employed have been raised dramatically making it extremely difficult to survive economically. It is a tragedy that doesn’t make sense. So for young architects it is very hard to find paid work and to not simply give up and move abroad. The scene has worsened in the last years. But then, the further challenge is to stay and try to make something out of this mess. To develop new tools and increase our critical force. To make proactive architecture.

What is the role of the public realm in Athens – or the Greek city in general?

Public space has been extremely devalued in all Greek cities for a very long time. The modern cities were built by small private interests without any care for bigger amenities and public space. There is often not enough space for pedestrians to walk on. The recent crisis has actually brought the attention of society back to the communal: the urban and natural environment became a focal point again.

The kitchen of the Nadja apartment.

-

I particularly enjoyed your Chicago Biennale participation, where you explored Athens’ “hidden potential”.

The hidden potential of Athens is the topic behind a lot of self-initiated projects that we have been doing for the city since founding our office. These vary from radical to immediately realisable. The Chicago Biennale project is called The Playfulness of the Real and presents pairs of the most extreme opposite parts of our work; urban proposals next to photographs of realised buildings. Among them, there are common ideas that keep resurfacing in ways that surprise us. For example the Petralona House resembles a city, the Nadja house is like Faliro Pier. The Flower shop is like Athens Heaven. It is a very surprising and fun project.

One of the ongoing debates about public space revolves around the “informal city” and how urban space can be created spontaneously by users. Do you think this is true in Athens?

It is very true in Athens, especially since the crisis. There are many examples of citizens’ initiatives, such as Atenistas, who gather and improve spaces on their own, such as cleaning vacant lots, or painting blind walls. Another example is a park in Exarcheia, a central neighbourhood in Athens, that used to be a parking lot, but residents claimed it and turned it into a green park. There are a lot of such initiatives but our concern is that vision and identity are often missing, so the resulting spatial qualities are typically very poor.

-

![]()

![]()

Left: Textured concrete façade of Petralona House. Right: Model of Petralona House (2015).

-

Point Supreme Architects was founded in Rotterdam in 2007 by Konstantinos Pantazis and Marianna Rentzou and is now based in Athens. Their work integrates research, architecture, urbanism, landscape and urban design.

PartnersKonstantinos Pantazis studied architecture at the National Technical University Athens (2002), and did a Master of Excellence in Architecture at The Berlage Institute Rotterdam (2002-2005). He has worked for a variety of offices in Athens and abroad including: MVRDV in Rotterdam (2007-08), Altoon and Porter in Amsterdam (2006), 51N4E in Brussels (2005), Farjadi Farjadi in London (2004), OΜΑ-Rem Koolhaas in Rotterdam (2003-04), Yushi Uehara in Amsterdam (2003) and Jun Aoki in Tokyo (2002), He currently teaches at Patras University.

Marianna Rentzou studied architecture at the National Technical University Athens (2002), and did her Master of Architecture at the Bartlett School of Architecture in London (2003-2004) followed by further studies at the Design Academy Eindhoven with Droog Design. After working in Athens for a while, she went to MVRDV in Rotterdam (2005-2006), then OMA - Rem Koolhaas in Rotterdam (2005, & 2007-2008). At OMA she worked on a wide range of large scale projects in the Middle East and led the Dubai Creek theatre and Dubai Next in Basel.

Ellie Stathaki is Architecture Editor at Wallpaper* magazine. She was born in Athens, raised in Larisa, trained as an architect at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and studied architectural history at the Bartlett in London. After a brief time in architecture practice, she focused on architecture journalism. She has contributed to Blueprint, The Financial Times, The Guardian, as well as the books 1,000 Buildings You Must See Before You Die (Quatro, 2007) and the World Atlas of Contemporary Architecture (Phaidon, 2007). She is the co-author of the New Modern House: Redefining Functionalism (Laurence King, 2010) and Todd Saunders: Architecture in Northern Landscapes (Birkhauser, 2012), and the author of the Wallpaper* City Guides for Antwerp (Phaidon, 2010 and 2013) and Athens (Phaidon, 2012). Occasionally she curates exhibitions.

Is there a public space that you feel works in Athens?

It might sound strange but the public space that works the best is the metro system. It is extremely clean and civilised. People seem very aware there. It is a very different world to the city above. It has to do with the fact that it is a space naturally free of cars and that it is well maintained. It is designed, after all. So people return this generosity. Another type of public space that works is the hills; also spaces that cars cannot access. For example the central Philopappou Hill; it’s paradise. Same goes for the beaches around the city.

…and which are the parts that you feel need rethinking? There are for example your proposals for Syggrou Avenue and Faliro Bay.

Nearly all parts of the city need rethinking! For sure the relationship between the city and the water is a critical issue, and that is the topic of these two projects - the coast and the connection to the sea. But other parts are also critical, such as green space and the completely ignored network of hills in the city. All these have a tremendous potential to transform the way the city is experienced on a daily basis and communicated (branded) at large, both at home and abroad.

Finally; what single thing would improve urban space in Athens?

The increase of soft surface, demolition of unnecessary walls and the prohibition of cars from certain areas.

-

Video: “Fountain” by Sofia Dona (2015)

Syntagama Square 5/6

Fountain by Sofia Dona (2015) – In front of the Greek Parliament and next to the fountain on Syntagma Square, a preacher preaches without being heard. The intense sound from the water fountain drowns out his words. The preacher shouts louder in an attempt to be heard over the fountain. An “oral battle” between religion, politics and an architectural symbol of prosperity is taking place in one of Athens’ most important public spaces, which has hosted countless demonstrations in the past and during these recent years of crisis. I (Sofia Dona)

-

![]()

Focus on Athenian maker projects by dpr-barcelona

![]()

![]()

![]()

-

As curators of the 2015 exhibition and symposium Adhocracy Athens uncube asked dpr-barcelona (Ethel Baraona Pohl and César Reyes Najéra) to focus on a selection of maker projects from groups “who are guided by the will to change the system by changing the way they make things themselves”.

dpr-barcelona (Ethel Baraona Pohl and César Reyes Nájera) is an architectural research practice based in Barcelona, dealing with three main lines: publishing, criticism and curating. They are the curators of the 2015 exhibition and symposium Adhocracy Athens.

The Adhocracy exhibition and symposium at the Onassis Cultural Centre in Athens in 2015 was focused on the relation of design, culture, and society within a global approach, but based on the dynamics of the local art, architecture and design. Adhocracy highlighted achievements by makers who are guided by the will to change the system by changing the way they make things themselves. It includes examples of makers whose work embraces open source design, and particularly emphasizes the idea of the commons in relation to production. Adhocracy Athens is the continuation of the research started for the 1st Istanbul Design Biennial in 2012, curated by Joseph Grima and associate curators Ethel Baraona Pohl, Elian Stefa, and Pelin Tan.

Adhocracy, as a concept, is nothing new. However, the term itself was coined in 1968 by Warren Bennis in his book The Temporary Society, and by 1970 had been made popular by the hand of Alvin Toffler and his international bestseller, Future Shock. Often used in the field of business, the concept became known as “adhocism” in the context of architecture and design in 1972, when Charles Jencks and Nathan Silver wrote a book with the same name. In it, Jencks wrote: “Adhocism is the art of living and doing things ad-hoc – tackling problems at once, using materials at hand, rather than waiting for the perfect moment or “proper” approach.”

The current socio-political and economic situation in Athens is going through a difficult moment that is not without controversy. The struggles and riots of recent years generated enough pressure to provoke a referendum on an EU bailout deal for the debt crisis, but this pressure wasn’t strong enough to translate the result of the vote – in which the Greek people rejected the austerity conditions of the proposed deal – into reality. The current local political and economic situation connected with the global approach of the networked society, along with the need to respond to that uncomfortable and unfair situation, has become a catalyst for several grassroots movements, collectives and independent groups that we show here. The examples we have chosen are those that are translating the concept of adhocracy into action: transforming a noun into a verb.

![]()

Exhibition view of Adhocracy Athens, 2015 (All images courtesy Adhocracy Athens, unless otherwise stated)

![]()

-

TRACES OF COMMERCE

—Following the financial crisis, Athens’ network of ground-floor spaces, that once housed the steaming engine of its local urban economy, has become a redundant landscape of vacancy. Urban space in many European cities has become increasingly monetised by private companies, but at the same time there has been renewed interest in approaches that transcend the rhetoric of law and urban policy; where the value of an empty plot or a derelict building is not defined solely by traditional economic metrics but is also determined according to the social relationships it can create and for the informal (or even immaterial) economic activity that can emerge there.

Against this backdrop, the Traces of Commerce project has brought activity back to one such vacant public space of Athens, the Stoa Emporon (Arcade of Merchants). In 2013 it was a stagnant, dead zone in the heart of the city, its small shops devoid of any commercial activity for more than a decade. Now it has been transformed into a transparent space of creativity and collaboration.![]()

-

NATIVE PRODUCTS

—The subject of food commands increasing attention from the fields of architecture and design, especially how it affects life in cities, from distribution infrastructures to domestic space. Since ad hoc processes allow people to do away with the language of marketing and challenge the rules of consumerism, it’s easy to find a relationship between food and an understanding of activity related to the “commons”, namely, the pooling and sharing of a set of resources. It’s also a good starting point from which to raise awareness about issues such as product lifecycles, ethical design, labour value, and connections between the local and the global.

Native Products is a workshop project created by papairlines who describe themselves as “the world’s first no-budget airline”, operating metaphorical “design flights” for their design, research and curatory practice. Attendees learn about the narrative of product lifecycles, design and ethical production by participating in the entire process, using nothing more than a few household tools and plants.

![]()

-

PO.IN-INC.

(POINTLESS INVENTIONS

INCORPORATED)

—Every day we see new trending technologies emerge from the fast-spreading, networked, digital realm. Large communities are often quick to adopt and then proclaim these new concepts to be “the most important innovation in years”. But it’s important not only to reflect critically on the techno-fetishism that surrounds the machines we create, but also to try and understand how the unconditional trust we have in technology can sometimes be counterproductive.

How many objects do you own without ever having really needed them? How many appliances do you own that are dysfunctional in design? To highlight the scale of wasteful manufacture of useless objects, Po.In-Inc., have proposed a series of DIY projects, such as their Universal Doodling Machine or the Drowning Mask, which deliberately aim to generate frustration. Created through an utter lack of necessity as a possible remedy to our ravenous accumulation of objects, they explore ways of making products that don’t work, malfunction or simply fall apart.![]()

![]()

-

SOUZY TROS

—In a set of dilapidated rooms in a former industrial complex in the Elaionas district, a collaborative project named Souzy Tros has been making a name for itself. It is a food and culture canteen dispensing “democratic hospitality” under the motto “Loveless – Hot Trahanas” (trahanas is a simple Greek soup made from cracked wheat and fermented milk). The project is the brainchild of artist Maria Papadimitriou, whose work is often concerned with the creation of a dialogue between different groups in society, and, on a broader scale, the position of Greece within Europe.

At Souzy Tros the extraordinary is demanded from ordinary actions, allowing guests to experience urban cooperativeness both as solidarity through action, and as a subject of conversation. It is a space where the act of sharing – food, conversation, space, performance, etc. – becomes the most “radical” act, the one most able to change our notion of “society”.![]()

-

ATHENS WIRELESS

METROPOLITAN NETWORK

—The gap between those who have an easy access to broadband services and those with no possibility to connect, either for economic reasons or due to the shortage of services in some areas of the Athens is a very real economic inhibitor. Despite the fact that the UN Human Rights Council deems freedom of expression and access to the internet to be a basic human right in 2011, the reality still is that there are many cities, or spaces in cities, lacking internet infrastructure.

Back in 2002, a grassroots initiative called the Athens Wireless Metropolitan Network (AWMN) was founded to provide wireless services based upon the protocols and philosophy of open-source software. The scheme has since expanded into a broad informal network of IT enthusiasts and professionals of all ages who have set up hundreds of active nodes a geographical reach that extends beyond the Greek border. Participation at all levels is open and free. This is a good example of adhocracy filling a gap when bureaucracy is too slow to provide a service. I

awmn.net![]()

-

Syntagma Square 6/6

On 6 March, 2016 Syntagma Square was occupied once again; this time with mountains of nappies, toys, dry food, socks, sleeping bags, baby slings and hundreds of other items destined for the port of Piraeus. Despite facing severe social and economic uncertainty themselves, a reported 10,000 Athenians turned up on the day to donate emergency supplies, loaded onto trucks via human chains, for refugees stranded at the port – demonstrating once again the spirit of resilience and awareness of social duty of citizens as they stepped in to bridge the gap between those in power and those in need. I (gk)

Image courtesy Polychorosket/Flickr (License)

-

In the Photo Booth with ...

John PawsonThe British firm John Pawson Architects are just completing their first project in Berlin: the conversion of a former WW2 telecommunication bunker into a private gallery space to house Southeast Asian artworks and Imperial Chinese furniture for collector Désiré Feuerle. One month before the official opening, uncube’s Sophie Lovell and Florian Heilmeyer met up with the renowned minimalist John Pawson on site to talk about quality concrete, found architecture and the power of raw space.

Interview by Sophie Lovell & Florian HeilmeyerPhotographs by Lena Giovanazzi

![]()

-

I remember joining you on a tour with David Chipperfield through his Neues Museum here in Berlin back in 2009. Did his famous “update” of that museum influenced your approach to this project in any way?

The Neues Museum is a complete masterpiece. I don’t think I’ve ever seen such a successful (what would you call it?) repurposing, restoration or remodelling. The materials, the thinking and the time taken to get it absolutely right – it’s awesome. Our project for Désiré Feuerle is a lot simpler. We didn’t want to change anything here. The bunker is so monumental on its own, with such a charged atmosphere, that we made very few interventions. Still we’ve done a huge amount of work! It has taken two years: the plaster had to come off the columns, the graffiti went, we cleaned the floors and the ceilings. What makes it so beautiful is the concrete engineering and the fact that even though it was just a functional railway command centre in the middle of the Second World War, the designers were still architects; the columns and proportions are works of art.

-

What other qualities did this 1942 bunker offer for a transformation into a gallery space?

It is a unique and extraordinarily monumental place with a strong character and strong atmosphere, which is why “found” buildings are perhaps so successful for housing art. When the accented lighting goes in, the art – some of it being sixth- and seventh-century Khmer sculptures – will look really quite mysterious. It will be a real experience, like Angkor Wat in a funny way.

But it is not all “as found”, you have inserted three new, long interior walls for example, with a shadow gap at the top…

Very few people have seen it as yet, but still some have asked: what interventions have you actually done in here? This (wall) is a functional device: everything to do with the heating, smoke extraction and dehumidifying all goes on behind. The shadow gaps at the top are purely functional – to allow the air to flow – they are not there to make the wall look like it floats.

-

With their metre-thick walls and ceilings, former bunkers are notoriously difficult to work with. What problems did you encounter here?

Well we knew the problems that were coming because we had to make some openings to get things through. When you are cutting through two-metre-thick walls it takes days. The ceiling is three and a half metres thick! And, obviously, it is all reinforced. It is top stuff as well: really high-quality concrete – the Allies never managed to damage it.

I understand there were flooding issues. Was it actually underwater when you started?

Part of the basement was flooded and during construction we had some issues because the basement is below the water table and there is a canal next to it. The basement was rather beautiful when it was flooded because the columns reflected in the water, like the cisterns in Istanbul.

Why would you argue for keeping the building instead of tearing it down and constructing something new in its place? Isn’t preservation going too far in this case? Or was it a more pragmatic decision?

No! I didn’t even think for a second about tearing it down. You do get clients who say: “I’d love to remodel this house” and you say: “No, there’s nothing to keep here”, but I can’t even think of the cost of trying to tear this down! Surely there is an argument for saying that this is very much part of the fabric of the city of Berlin. It’s a monument in a sense. And I think that it is brilliant that somebody like Désiré has found his dream place for his collection. It would hardly be usable for anything else.

-

Photos: Gilbert McCarragher, courtesy John Pawson Architects.

John Pawson has spent thirty years making rigorously simple architecture, based on the qualities of proportion, light and materials. Early commissions included homes for the writer Bruce Chatwin, opera director Pierre Audi and collector Doris Lockhart Saatchi, together with art galleries in London, Dublin and New York. Subsequent projects have spanned a broad range of scales and typologies, from Calvin Klein’s flagship store in Manhattan and airport lounges for Cathay Pacific in Hong Kong, to a Cistercian monastery in the Czech Republic and sets for new ballets at London’s Royal Opera House and the Opéra Bastille in Paris. He is currently engaged in the project to create a new permanent home for the Design Museum in the former Commonwealth Institute in London, scheduled to open in late 2016.

How is your design for the new Design Museum in the former Commonwealth Institute in London progressing? How does building a museum in London compare to building one in Berlin in your experience?

The Design Museum is very different. Again we had been given an extraordinary building, which you could not reproduce today. And it’s in the middle of a park in the middle of London; and to have a roof like that [it has a shell concrete hyperbolic parabaloid roof construction, ed.], which is kind of mad. But that museum has 100 employees; there are so many departments, so many curators... Here, there’s just Désiré. It is a very singular and pared back building, which is why we were able to leave it very much as it is: just two fantastic floors, a small office area, reception, lockers and loos. I

-

![]()

-

FURTHER READING

Magazine ESSAY20

Renegotiating the Urban Commons

Francesca Ferguson introduces the issue

Magazine Essay20

Architecture of the Civic Economy

Indy Johar's manifesto for soft power

Magazine Case Study34

Connected Communards

Mount Telaithrion, Euboea, Greece

Blog Interview10 Dec 2014

Athens Unplanned

Platon Issaias on the politics of ‘informal’ urbanisation

Blog Building of the Week13 Nov 2013

The troubled tale of a sleeping giant

The National Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens

Blog Interview05 Mar 2015

Protocols of Athens

Interview with Aristide Antonas

Search our archive! -

![]()

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Form follows feminine.«

Oscar Niemeyer

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents