The artist, designer and writer Sascha Pohflepp is an expert on the manifold implications of space travel – technological, cultural, mystical, and weird. He's designed food for outer space, built narratives around alternate universes and metaphorical spaceships, and regularly draws on his encyclopedic knowledge of science fiction to speculate on the future. Count your lucky stars: uncube has just gathered serious insight into his newest plans and projects as a conclusion to our month of all things “space”.

--

Your recent project “Seasons of the Void” imagines fruit that could be grown on a spaceship en route to Mars. Why grow food instead of bringing it?

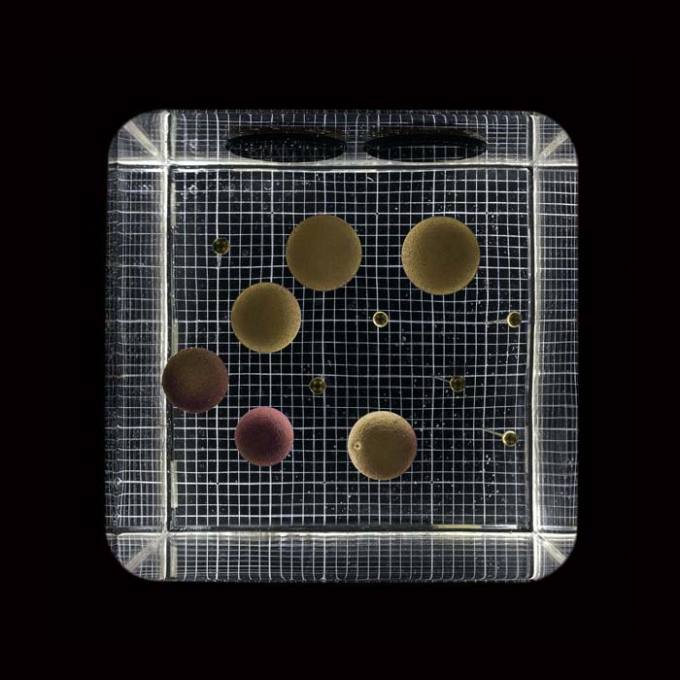

“Seasons of the Void” is a project that Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, Andrew Stellitano and I created as a response to the proposed use of synthetic biology for growing food that could sustain astronauts during long-range space missions. Since humans are still using chemical rockets to escape the gravitational pull of Earth, the cost in fuel in relation to payload is fantastically high. Growing provisions during the trip in space instead of launching them could result in a spacecraft that is 30 tonnes lighter.

There is a long history of growing things in space – a whole section of Moscow’s Museum of Cosmonautics is devoted to plants. However, there is also a long history of failed space-food experiments, especially during the American Gemini program. Synthetic biology as a technology is such an attractive solution because it offers the potential to design edible organisms according to the particular spaceship environment.

How do you propose to grow the organisms?

Because the ship has no large windows through which photosynthesis could happen, energy for growth would have to be provided through the ship’s electrical systems, which take in energy through solar panels. Instead of converting the energy back into light, the organism, in this case a modified yeast culture, could be altered to consume electric energy directly through electrosynthesis, growing around an electrode in a liquid medium until it is ready to be harvested and eaten.

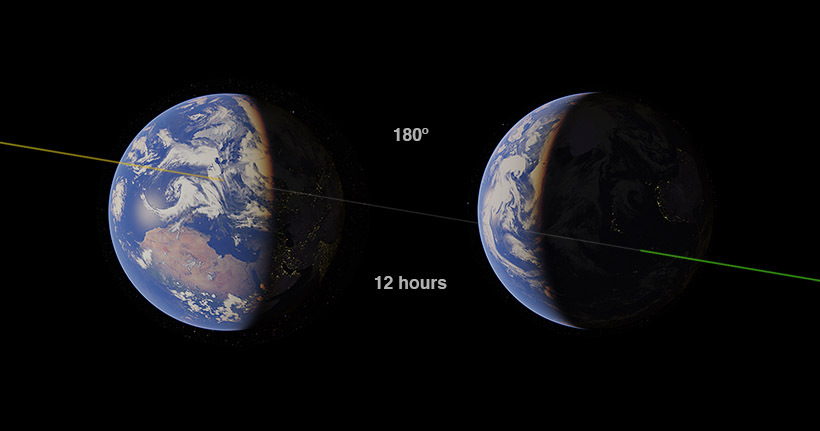

Though we chose to focus on the aesthetics and implications of the process, we did consult with scientists actively working on similar projects. We ran computer simulations to generate data on how much sunlight the ship would receive during the proposed routes from Earth to Mars to figure out how that would affect the electrosynthetic organism’s growth rate. What we perceive as seasons on Earth emerge from celestial mechanics, mainly the inclination of the planet in regard to the Sun as it wobbles around its axis. As the ship traverses the inner solar system on its way to Mars it would beocme a celestial body in its own right, receiving different amounts of energy at different times. This would lead to varying growth rates, which would likely be visible to the naked eye when the harvested fruit is cut open – like the rings on a tree.

Would cultivating crops in space lead to a type of agrarian culture? Are “seasons” necessary to simulate circadian rhythms in space? What is relationship between imagining space food and imagining space society?

Answering questions about Martian society is fascinating but difficult without becoming too speculative. Whether human colonisation of Mars would lead to an agrarian society has been explored in excellent science fiction like Philip K. Dick’s short story The Days of Perky Pat and Kim Stanley Robinson’s Mars trilogy. In any case it seems certain that astronauts will have to produce their own food via manual labour to sustain themselves so far away from the type of plentiful supply missions that the ISS receives – and this will be possible since the soil in a controlled atmosphere is believed to be capable of supporting plant life (see Carlos Monleon-Gendall’s project Martian Terroir in uncube No. 19). NASA has already put a lot of research in estimating numbers for some of those questions, especially in the 1970s and 1980s in the context of Gerard O’Neill’s visions of space colonies (also in uncube No. 19) and later as part of the Biosphere experiments in the Arizona desert, all of which contain a certain cultural echo of the American frontier. For our part we like to imagine that astronauts would become part-time “farmers of the void”.

Do artists and designers play a specific role in exploring the “human” element of technological development?

Technological development is driven by a multitude of forces and it zig-zags through history, as Stanisław Lem so lucidly pointed out in his 1967 non-fiction work Summa Technologicae. Technological development as a product of culture is as human as anything else, so I would resist the thought that non-engineers have a specific role – many technological developments were first thought up in fields like literature and only later realised as an engineered product. Practitioners who are somewhat peripheral to the mainstream of technological narrative are more free to explore other proposals and their effects than those who work in a corporate or a military context.

Criticality and speculation are the two terms that often come up regarding art and design, but such complication is not always welcome in fields that put a great emphasis on action, such as engineering. Luckily, other forms of knowledge seem to be taking hold as the internet continues to become the world’s de-facto culture. In art just as much as in science, curiosity is a valid currency.

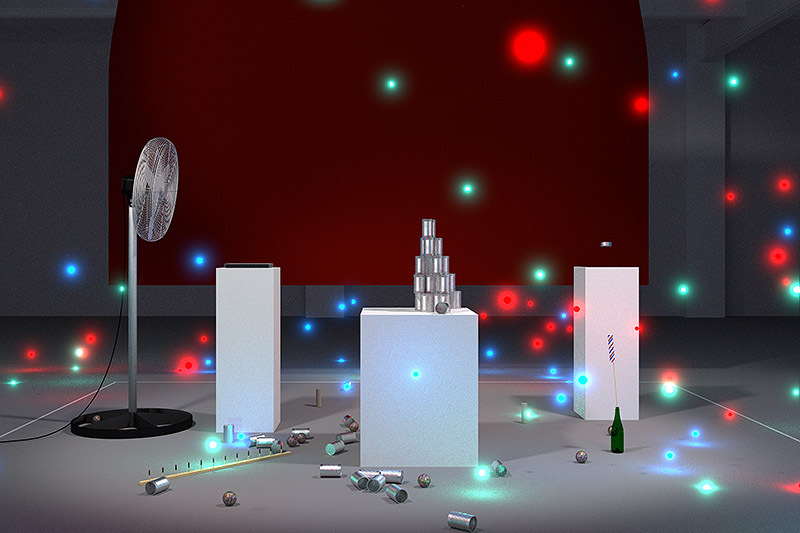

Your recent exhibition “Elsewheres: On Gliese 667 Cc”, refers to a potentially-habitable extrasolar planet – suggesting alternative realities lived on distant planets. Could you explain the exhibition and its inspiration?

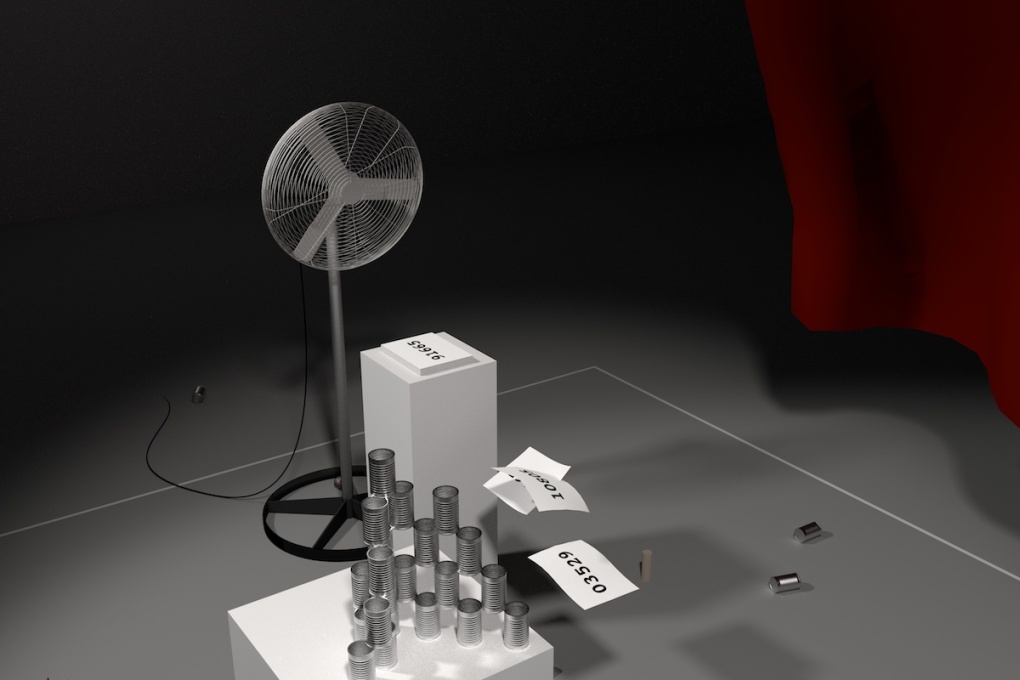

“Elsewheres” was conceived together with (the interaction designer) Chris Woebken as a series of installations which turn simulation modelling into an artistic medium, not least to reflect on its epistemic role in regard to climate change. On Gliese 667 Cc, objects would fall more violently due to the planet’s increased gravity. We modelled a simulation of objects falling on the planet, and then its results were manually re-introduced to the exhibition space.

Long before digital technologies developed, astronomy and physics provided a way of thinking about virtual reality. Is there a relationship in your work between the concept of space travel and the idea of the virtual?

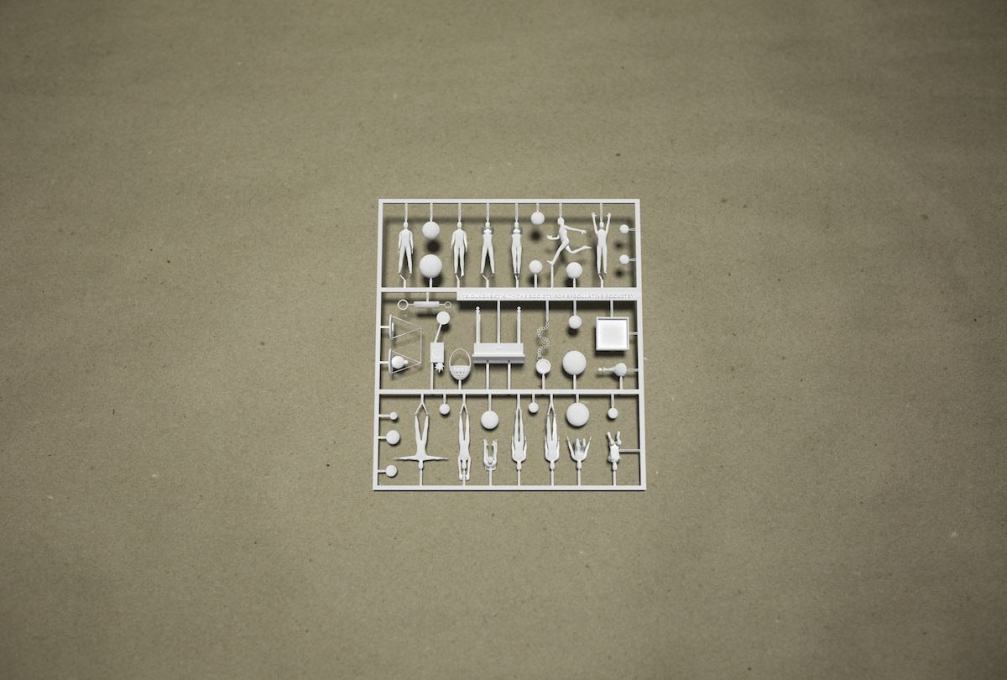

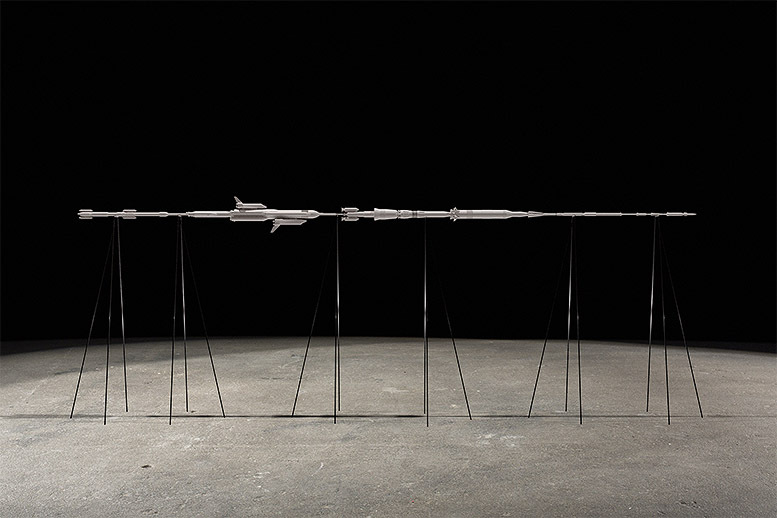

If you think about terms like cyberspace there is a a certain kinship between the idea of an interplanetary void and that of the virtual, a boundless inside of the machine that is only limited by the capacity of its memory which immediately conjures images of Tron and other stories. The notions of weightlessness and floating are also recurring aspects in many early depictions of cyberspace and interplanetary space. Russian physicist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, who also laid down the mathematical foundations of rocketry, was one of the first to depict floating humans in space in lovely drawings, which Chris Woebken and I have just recently recreated as a scale model for a new project called "The Society for Speculative Rocketry".

In a video/installation project you made called “Forever Future”, an actor portrays a character who, disappointed by retro promises of a life in outer space that did not come true, creates his own space programme. What is the programme like?

The character in “Forever Future” represents a counterpoint to narratives of linear technological progress through the fictional person of Robert Walker, who uses his analytic mind to create a “space mission” of his own. After realising that he will never go to space himself, he starts systematically preserving the unrealised visions of his lifetime in a symbolic space ship kept in a storage facility. Walker is a metaphor or placeholder for a cultural imaginary which stores such visions and allows them to periodically resurface, never letting them truly die.

Although he shares some traits with Tsiolkovsky, the character of Robert Walker is based on Jack Whiteside Parsons, one of the four founders of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Living in Pasadena, California in the 1940s, Parsons not only invented the fuel for the Space Shuttle’s booster rockets but was also very much into the occult – he was in fact Aleister Crowley’s favorite disciple at the time. Individuals upon whose shoulders some of the greatest achievements in human history rest were, by the common definition, rather weird. This was not necessarily because they were singular geniuses, but because they had a broader sense of their field than their contemporaries. That Tsiolkovsky and Parsons were both actively involved in science fiction (Parsons was a member of the Los Angeles Science Fantasy Society) is testament to their personal desires to consider the broader meaning of their work and the fact that they understood narrative as a vital part of the way technology evolves and how it is embedded within human culture.

Walker says at one point in the movie: “I miss the future I was promised as a kid… I guess you could say that I developed a kind of nostalgia for the future.” Do you also experience future nostalgia?

I can pinpoint when the idea of life in space was put into my head. It was in a supplement to the German comic magazine YPS which had on its cover a painting by Chris Foss and contained paintings of those space colonies which I now know were personally commissioned by Gerard O’Neill at NASA in the mid-1970s. This future I definitely miss, because vast space stations had been promised for the 1990s, tied to a window of opportunity afforded by the Cold War, but then world history and the sheer scale of it got in the way.

Why do you think there has been such a renewed widespread public interest in space travel lately?

Surely because of individuals like Richard Branson and Elon Musk and their entrepreneurial push into the field of space exploration. Once it becomes profitable to go to space we will see remarkable things – there is no such thing as a void for such forces. But we are also propelled the unfulfilled visions around space which we have collectively accumulated during the twentieth century, which we still can’t forget.

-Elvia Wilk

Sascha Pohflepp is a German-born artist, designer and writer whose work probes the role of technology in our efforts to understand and influence our environment. His “Camera Futura” is currently on view at FACT Liverpool, and “Elsewheres” will be exhibited at LEAP Berlin from 5 April. www.pohflepp.com

See uncube No.19: SPACE for more intergalactic intel.