-

Magazine No. 21

Acoustics

-

No. 21 - Acoustics

-

page 02

Cover

Acoustics

-

page 03

Editorial

Acoustics

-

page 04 - 13

The Hear and Now

Jonathan Bell in conversation with Yasuhisa Toyota of Nagata Acoustics

-

page 14

Parabolic Poem

The Philips Pavilion

-

page 15 - 16

Pump up the Volume

Arata Isozaki and Anish Kapoor’s inflatable concert hall

-

page 17

Dead Silent

Anechoic Chambers

-

page 18 - 23

Aural Prosthesis

Lev Bratishenko on Arup’s Soundlab and the rise of virtual acoustics

-

page 24 - 25

David Byrne

"Playing the Building"

-

page 26 - 28

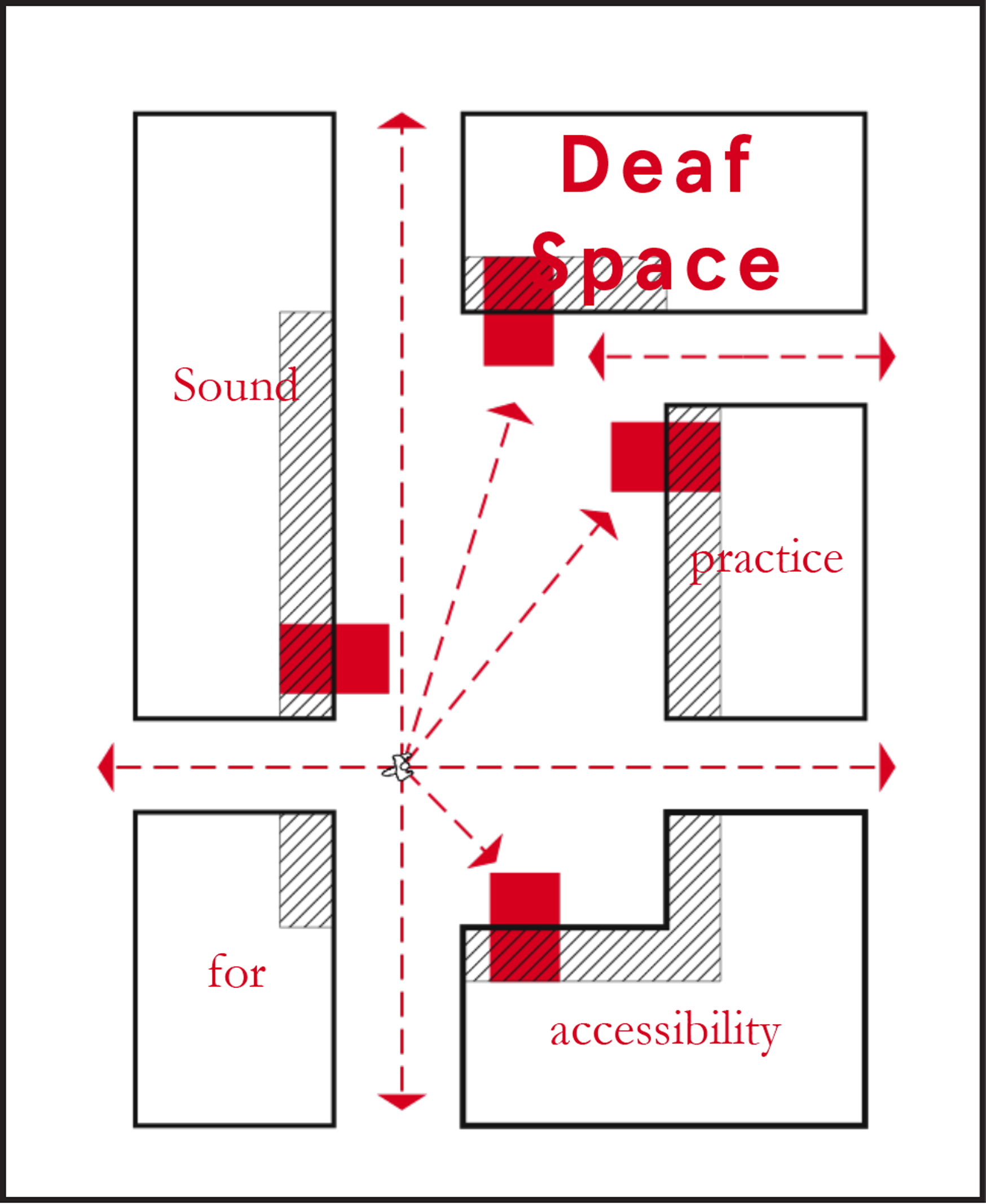

DeafSpace

Sound Practice for accessibility

-

page 29 - 30

Symphony in Concrete

Hans Scharoun's Philharmonie

-

page 31 - 38

His Master’s Voice

Interview with Edgar Wisniewski, Hans Scharoun's "silent" partner

-

page 39 - 41

Play it Loud

Soundsystems designed for supergroups

-

page 42

Yuri Suzuki

"Ishin-Den-Shin"

-

page 43 - 46

Music Boxes

Vredenberg Concert Hall in Utrecht

-

page 47 - 49

Acoustic Ecology

Planning urban soundscapes

-

page 50 - 52

Bookmarked

Guest reviewed by Carson Chan

-

page 53

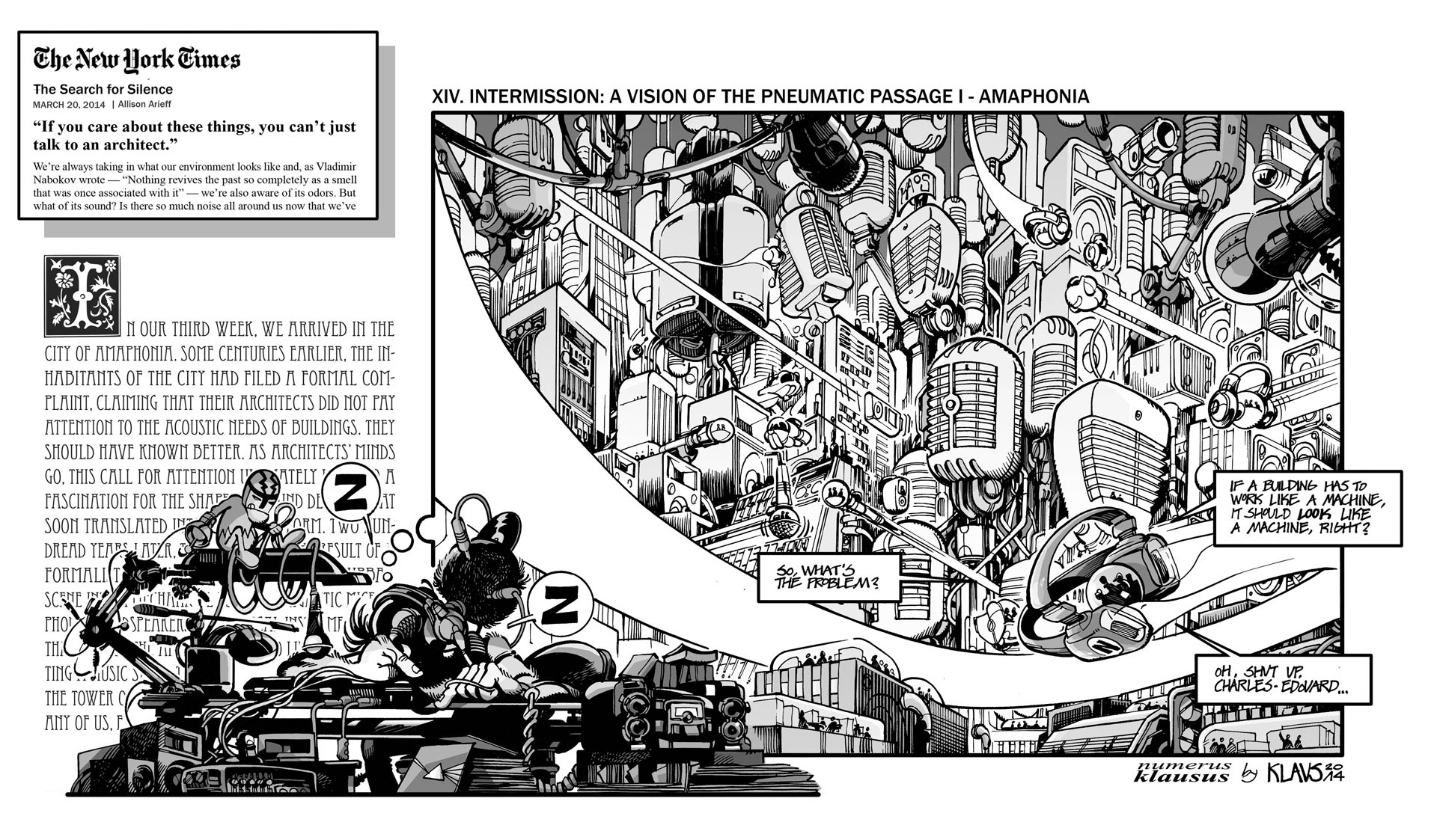

Klaustoon

XIV. Intermission: A Vision of the Pneumatic Passage I - Amaphonia

-

page 54

Next

Water

-

-

uncube's editors are Sophie Lovell (Art Director, Editor-in-Chief), Florian Heilmeyer, Rob Wilson and Elvia Wilk; editorial assistance: Susie S. Lee and Leigh Theodore Vlassis; graphic design: Lena Giavanazzi; graphics assistance: Madalena Guerra. uncube is based in Berlin and is published by BauNetz, Germany's most-read online magazine covering architecture in a thoughtful way since 1996.

![]()

With buildings like concert halls, acoustics are a prime generator of form, yet all architecture creates and reflects the sensory tonal environments in which we live. Nevertheless, the technology allowing in-depth understanding of how sound affects and is formed by space has lagged way behind in our visually fixated world – until recently.

uncube turns 21 with a whole issue dedicated to sound in built space; tuning in to surprising stories about acoustical masterpieces, sounding out audio experts and pricking up our ears towards cutting-edge advances in the world of acoustics.

Listen up as uncube goes audio.

Cover image: Guitar (Photo: Andreas Mierswa and Markus Kluska)

-

The

Hear

and

NowA conversation with acoustics maestro Yasuhisa Toyota

By Jonathan Bell

Museo Del Violino Chamber Hall

![]() Location: Cremona, Italy

Location: Cremona, Italy![]() Architect: ArkPaBi

Architect: ArkPaBi![]() Date: 2012

Date: 2012![]() Room volume: 5,300m³

Room volume: 5,300m³![]() Seating capacity: 460

Seating capacity: 460![]() Reverberation time (mid-frequency, occupied): 1.4 seconds

Reverberation time (mid-frequency, occupied): 1.4 seconds ![]() Ceiling + walls: plaster, wood

Ceiling + walls: plaster, wood ![]() Audience floor: wood

Audience floor: wood ![]() Stage floor: Alaskan yellow cedar

Stage floor: Alaskan yellow cedarPhoto: All images unless otherwise noted courtesy Nagata Acoustics.

-

The sound of space is one of the most complex engineering problems faced by the architect. People have been building structures for performance for millennia, but it’s only in the last century that we′ve started to understand why some physical spaces sound better than others.

Yasuhisa Toyota is one of the world′s leading acousticians today. As President of the US division of Nagata Acoustics, a company set up in 1971 by Dr. Minoru Nagata, Toyota has worked on some of the most significant performance venues of the past thirty years. He has also seen the technical sophistication of his profession expand exponentially since his first project, Suntory Hall in Tokyo, designed by Yasui Architects, was completed in 1986.

On the surface, the contemporary concert hall appears to be a classic example of architectural showboating. As a prestigious cultural building, a hall is a prime commission, something every architect aspires to creating. Yet the physical shape of a hall is only half the story. For a building to be a success, it must also sound precisely right. Toyota and his company are involved right at the start of the design process: “We have to start collaboration as soon as possible with the architects, especially when they are thinking about their inspiration or design direction”, he explains from his office in Los Angeles. “For architects, the typology is very important – different architects think in different ways. There are many different shapes but they don’t always work acoustically.”![]()

-

Suntory Hall

![]() Location: Tokyo, Japan

Location: Tokyo, Japan![]() Architect: Yasui Architects

Architect: Yasui Architects![]() Date: 1986

Date: 1986![]() Room volume: 21,000m³

Room volume: 21,000m³![]() Seating capacity: 2,006

Seating capacity: 2,006![]() Reverberation time (mid-frequency, occupied): 2.1 seconds

Reverberation time (mid-frequency, occupied): 2.1 seconds ![]() Ceiling: gypsum board

Ceiling: gypsum board ![]() Frontal wall: wood-surfaced gypsum board on concrete

Frontal wall: wood-surfaced gypsum board on concrete ![]() Side wall: wood-surfaced gypsum board, woodchip board

Side wall: wood-surfaced gypsum board, woodchip board ![]() Floor: wood board on concrete

Floor: wood board on concrete ![]() Reflectors: plexiglass

Reflectors: plexiglass -

Toyota gives a potted history of contemporary acoustic design. It wasn’t until the Boston Symphony Hall of 1900 that an engineering approach to acoustics was first used. Designed by the pioneering Chicago firm of McKim, Mead and White, it was acoustically engineered by Wallace Clement Sabine, a professor of physics at Harvard who defined what we now know as reverberation time, thanks to some ad hoc experimentations in the college′s lecture halls.

Barely a few decades before, major concert halls like the Royal Concertgebouw in Amsterdam (1886) or Vienna′s Musikverein (1870) achieved their acoustical brilliance through luck rather than judgement.

Both followed the traditional “shoebox” model of room design, with a happy combination of visually harmonious and acoustically excellent auditoria. “So far we have two traditional shapes – the ‘shoebox’ and the ‘vineyard’, where the audience is arranged around the stage”, Toyota explains, adding that “the vineyard-style was first used by Hans Scharoun for the Berlin Philharmonie – it was epoch-making, a milestone.”

Scharoun’s hall revolutionised concert hall design, not only in the expressionist, abstract gold-coloured façades, but inside, where a raised stage was surrounded by terraces of seating that seem to cascade around it. Acoustically it is highly rated and provided the model for many subsequent structures. While modern halls are neatly divided between these two forms, the architectural approach demands to be unconstrained. Traditional methods of deciphering the patterns of sound before a building is completed are no longer enough.

-

“The computer technology we use has only been developed in the last 20 years” says Toyota. “Before that we used physical scale models”. For the Suntory Hall, for example, divining the acoustics meant building a sizeable and expensive scale model. “If possible, we build a 1:10 model – this isn’t small, for it means that a 20-metre-high auditorium is represented by a two-metre-high model. You can walk into it – it’s huge.” He goes on: “the major benefit of a model is that we can use actual sound, in 1:10 scale waves.

» We used to convert to these higher frequencies by changing the speed of a cassette recorder «

This means the frequency of sound used in the model should be ten times higher than normal. We used to convert to these higher frequencies by changing the speed of a cassette recorder – that was how we did Suntory Hall – now computers have taken over.” Major recent projects by Toyota include Jean Nouvel’s Koncerthuset in Copenhagen and the Helsinki Music Center by LPR Architects. Both still required massive 1:10 scale models to hone and refine the sound of the performance space. “We use them to check the detrimental echoes.

-

Walt Disney Concert Hall

![]() Location: Los Angeles, USA

Location: Los Angeles, USA![]() Architect: Frank Gehry

Architect: Frank Gehry![]() Date: 2003

Date: 2003![]() Room volume: 30,600m³

Room volume: 30,600m³![]() Seating capacity: 2,265

Seating capacity: 2,265![]() Reverberation time (mid-frequency, occupied): 2.0 seconds

Reverberation time (mid-frequency, occupied): 2.0 seconds ![]() Ceiling: Douglas fir

Ceiling: Douglas fir ![]() walls: Douglas fir

walls: Douglas fir ![]() Floor: oak

Floor: oakPhoto courtesy Los Angeles Philharmonic

-

Danish Radio Concert Hall

![]() Location: Copenhagen, Denmark

Location: Copenhagen, Denmark![]() Architect: Jean Nouvel

Architect: Jean Nouvel![]() Date: 2009

Date: 2009![]() Room volume: 28,000m³

Room volume: 28,000m³![]() Seating capacity: 1,800

Seating capacity: 1,800![]() Reverberation time (mid-frequency, variable acoustics, occupied): 1.5-1.9 seconds

Reverberation time (mid-frequency, variable acoustics, occupied): 1.5-1.9 seconds ![]() Ceiling + canopy: microshaped veneer + gypsum board

Ceiling + canopy: microshaped veneer + gypsum board ![]() Balcony and walls: microshaped multiplex board, perforated gypsum board

Balcony and walls: microshaped multiplex board, perforated gypsum board ![]() Audience floor: wood parquet + gypsum board

Audience floor: wood parquet + gypsum board ![]() Stage floor: Port Orford cedar

Stage floor: Port Orford cedarPhoto: Brahl Fotografi

-

It’s still the only way to discover these, as computer simulations can’t detect echo problems”, Toyota explains. Elaborate and expressive shapes are nothing if they’re not acoustically suitable. “It’s not easy to change a design once you’ve built a scale model, so we start with a computer model, which is far more flexible,” he continues, explaining how computation plays an essential major role in modern hall design.

Perhaps the best example of how the game has changed is Frank Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, completed in 2003. “What we could study in terms of room shape was very limited before, but now we are looking at developments in architectural design”, says Toyota. “Gehry won the competition in 1988 or 1989 and we were chosen in the selection. Back then, they didn’t have CAD software, and we were still developing our programmes on Workstations, which are very big computers”. After the basement parking garage was built, the project was placed on ice in 1996. “When they started again, it was after Gehry had completed Bilbao and there had been these big developments in computer design”, Toyota says, “so when Disney re-started the design it was totally different to the original. We had to develop our own technology to follow them”. The end result is specialist software linked to high-end CAD packages: “we can now do an acoustic check in a seamless way”.

Toyota believes that the vineyard style “gives architects more flexibility in terms of shape”, whereas in the shoebox, the room size and ceiling heights are far more limited: “a box is a box”. That said, “Nagata has to be accommodating. If the architect chooses the shoebox style, we will follow the design – it depends on the architect, the client and the programme. It’s not a simple process.”

-

Helzberg HALL

![]() Location: Kansas City, USA

Location: Kansas City, USA![]() Architect: Safdie Architects

Architect: Safdie Architects![]() Date: 2011

Date: 2011![]() Room volume: 19,000m³

Room volume: 19,000m³![]() Seating capacity: 1,600

Seating capacity: 1,600![]() Reverberation Time (mid-frequency, occupied): 2.1 seconds

Reverberation Time (mid-frequency, occupied): 2.1 seconds ![]() Ceiling: sandblasted plaster

Ceiling: sandblasted plaster ![]() Walls: plaster

Walls: plaster ![]() Audience floor:

Audience floor:

oak![]() Stage floor: Alaskan yellow cedar

Stage floor: Alaskan yellow cedar -

Yasuhisa Toyota studied at the Kyushu Institiute of Design and is one of the world’s leading acousticians. He has been chief acoustician on over 50 projects worldwide, including the Walt Disney Concert Hall, Suntory Hall in Tokyo, the Bard College Performing Arts Center in New York, and the Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts in Kansas City. Current projects include acoustics for Herzog and De Meuron’s Elbphilharmonie concert hall in Hamburg, Germany, due for completion in 2017. He is the company director and US Representative of Nagata Acoustics of Tokyo.

Ultimately, fine acoustics is a subjective art. Measurable statistics like reverberation time only tell half the story. “When I was working on Suntory Hall, I explained how reverberation time worked to the clients. They asked if it was something like an alcohol percentage; did the number guarantee the quality of the whisky? No. But how can you describe the quality if not through a number? It opened another eye for me.” You can’t quantify a concert hall through statistics. “It’s like reading an X-ray”, Toyota continues, “it’s not always clear to us, but a doctor with many years of experience can make an evaluation without numbers”.

Toyota’s involvement with the Disney Hall gives him the perfect excuse to attend performances whenever he can. As a result, it’s one of his favourite works. “I go to concerts at the Walt Disney Concert Hall regularly”, he admits, adding that the “Suntory Hall is also important to me – it was the first big concert hall in our history”. Technology might improve, but the fundamental requirements of unamplified performance will always remain the same. Nagata Acoustics is a job for both golden ears and infinite patience, as the firm continues to translate modern architectural visions into acoustic excellence. I

-

PARABOLIC POEM

• The Philips Pavilion •

In 1958 Le Corbusier was too busy working on Chandigarh to focus his attention on a comparably minor commission: the Philips Industries Pavilion at the World’s Fair in Brussels. So Corb outsourced the project to Iannis Xenakis – the renowned Greek composer who at that time was up-and-coming in the architect’s firm – with the assignment to create an “electronic poem”. How’s that for a brief?

As with his musical compositions, Xenakis applied complex mathematical models to formulate the design, coming up with an arrangement of nine hyperbolic parabloid shapes made from pre-stressed concrete and girded by steel tension cables. Xenakis also wrote a composition, Concrète PH, derived from manipulated recordings of burning charcoal. In the main interior cavern, or “stomach”, Corbusier and composer Edgar Varèse engineered a (perhaps overly) complicated multimedia piece showcasing as much new technology as possible: 350 speakers were embedded in the walls, slides and films were projected across the curved surfaces, and 51 different lighting configurations illuminated the space. I (ew)

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

-

![]()

Photos: Iwan Baan

Pump up the Volume

Arata Isozaki and Anish Kapoor’s inflatable concert hall

The Ark Nova inflatable concert hall was conceived in the aftermath of the 2011 tsunami in Japan. It is a reusable venue designed to tour the most badly affected areas, supplementing a still patchy live arts provision for the local population. The project was initiated by the Lucerne Festival, a Swiss international music event that traditionally has strong links to Japan. It takes its inspiration from Noah’s Ark pitching up after the biblical flood, though it does not carry “people and animals to escape from disaster” – as the Festival’s artistic director Michael Haefliger puts it – but is “packed with music and various arts” for the “long-term rebuilding of culture and spirit”.

-

Arata Isozaki, born 1931 in Ōita, Japan, studied architecture at the University of Tokyo, graduating in 1954. After working in the office of Kenzo Tange, he established his own firm, Arata Isozaki & Associates, in 1963. He has since built around the world including in Europe, Central Asia, the Middle East, China and North America. Celebrated projects include the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) in Los Angeles (1981-86) and the Kyoto Concert Hall (1991-95). In 2005, Arata Isozaki founded an Italian branch of his office, Arata Isozaki & Andrea Maffei Associates. A current project includes an office tower in the new CityLife Business District of Milan. He was awarded the RIBA Gold Medal in 1986.

Anish Kapoor, born 1954 in Bombay, India, has lived and worked in London since moving there in the early 1970s to study art at the Hornsey College of Art, then at the Chelsea School of Art.

He represented Britain in the 44th Venice Art Biennale in 1990 and was awarded the Turner Prize in 1991. Celebrated projects since include his 2002 Unilever Commission Marsyas in the Turbine Hall at the Tate Modern, Cloud Gate in Chicago's Millennium Park; Leviathan at the Grand Palais in Paris in 2011; and ArcelorMittal Orbit, commissioned as a permanent artwork for London's Olympic Park in 2012. He received a knighthood in 2013.

![]()

The design of the building, looking somewhat like a giant plum, is a cooperation between Japanese architect Arata Isozaki and Indian-born, London-based artist Anish Kapoor. At 30 metres wide, 36 metres long and 18 metres high, its structure is a lightweight translucent purple membrane, inflated by a series of air pumps in around two hours – which can be deflated, folded up and loaded onto a truck for easy transportation between venue sites. It provides a flexible space that can accommodate audiences of up to 500 and all types of stagings and performances: from traditional orchestral concerts to in-the-round multi-stage contemporary music events.

With acoustics an important consideration, airlocks isolate the hall from the noise of the pumps, whilst a floating “acoustic cloud” bounces sound back down to the audience. This is supplemented by a more traditional method: cedar wood reflectors behind the stage. These, like the seating, are made with timber from the tsunami-damaged forests around the Zuiganji Temple, a symbol of the city of Matsushima, the first venue for the concert hall in October 2013. A tour of the region is still under preparation. I (rgw)

-

DEAD SILENT

• Anechoic Chambers •

Though an anechoic chamber may resemble a form of medieval torture device, these scientific facilities perform a role that is quite benign. Sound waves in the chamber are trapped between the surfaces of spiked foam or fibreglass baffles lining the walls. This creates an endless rebounding effect until the waves are absorbed, eliminating echo and sound decay to produce an environment ideal for recording and testing sound equipment. The resulting silence is so profound that minute bodily noises become intensified – a heartbeat, the sound of swallowing, the rustling of clothing and the movement of bone and muscle suddenly seem deafening. While some describe experiencing the dead silence as tranquil, others can feel panicked and even nauseated, or report hallucinations. In these spaces there’s nothing to hear but yourself. I (ssl)

Anechoic chambers register at about -9 decibels, whereas the human ear can only register sounds above 0. Alastair Philip Wiper photographed the anechoic chambers of Denmark’s Technical University for a series on the beauty of scientific research facilities.

-

![]()

Arup’s SoundLab and the rise of virtual acoustics

by Lev Bratishenko

Acoustic study of the Greater London Authority (GLA) building, designed by Foster + Partners. (Animation: Arup Acoustics)

-

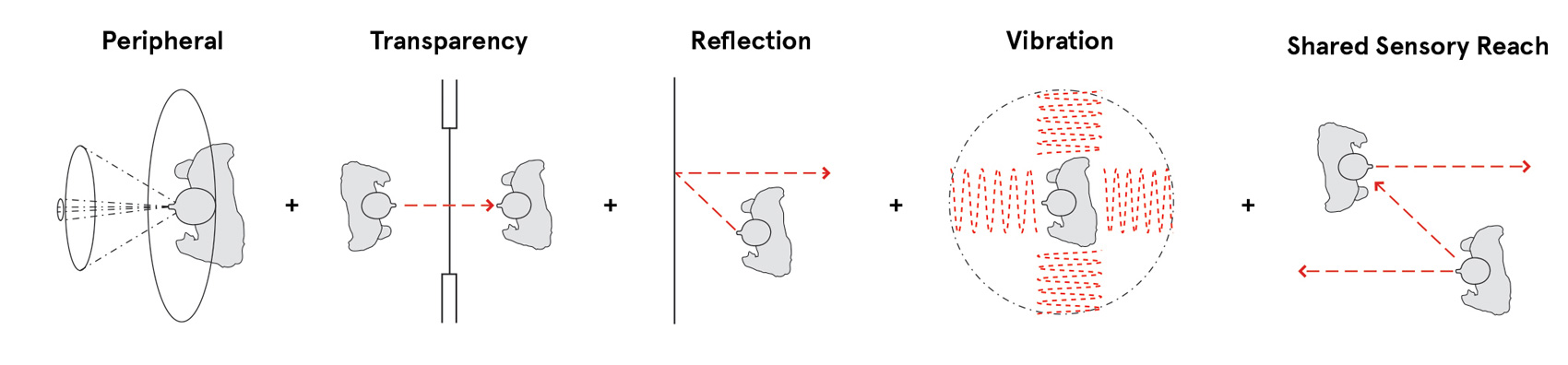

The technology to hear spaces that don’t exist has been around for decades. The hardware and software that make it possible have developed alongside leaps in processing power. In recent years virtual visuals in the form of 3D rendering have moved from laboratories to studios, mainframes to desktops, and laptops to smartphones. Virtual listening has lagged behind, but it is coming soon to the personal device. What are we going to do with it when it gets there?

It is a strange fact that most architects don’t have to study acoustics, but there are others involved in buildings that probably shouldn’t have to. Manual methods and early software for predicting how spaces sound are expressed in graphs and charts that risk limiting the discussion of acoustics to expert maneuvers of ego, performed in jargon. Listening is more democratic, even if people listen differently. That’s why musicians take ear training.

Auralisation is the process of making data audible, but before that was reasonable to do for every project, visual tools were used. The global engineering firm Arup has been in the virtual acoustics business since 1990 and operates an acoustic consultancy with sound labs in all major offices. For Norman Foster’s Greater London Authority (GLA) building, completed in 2002, Arup built an in-house plugin for 3D Studio Max to iterate the design.![]()

Sketch of the GLA building. (Image: Foster + Partners)

-

Arup’s Global Acoustics Lead, Raj Patel, describes the original chamber design as “a big glass box that curves all the way to the top” and analysis indicated that it would have too excellent an echo. Echo is okay for some music, but not for speech. The simulation was first run in 2D for the sake of speed, and once an approach of offset balconies and sound-absorbing treatment looked like it would work, modelled in 3D overnight. “It took every single computer we had in the office, daisy-chained together”, remembers Patel.

Today the auralisation of performing arts spaces is SoundLab’s bread and butter. Sound waves are modelled using algorithms to predict the intensity and direction of reflections off surfaces with different acoustic characteristics in 3D.For the most complex curved spaces, physical models with miniature speakers and receivers at ultrasonic frequencies are still used. The result is what Patel calls an “acoustic signature” that represents the response of the room to a specific signal.

Physically, the lab is a sphere of speakers housed in a sound isolated room, softly humming with computers. You sit in the middle, exposed on a high chair, and hope nothing horrible happens. What you hear is the live combination of the acoustic signature of a room and a sound, like somebody playing the oboe or talking (recorded without echoes in an anechoic chamber.) The power of the system is that it can switch “rooms” in milliseconds, a kind of teleportation by aural prosthesis.![]() City Hall, London by Foster + Partners. (Photo: Dennis Gilbert)

City Hall, London by Foster + Partners. (Photo: Dennis Gilbert) -

Hybrid room acoustics simulation software RAVEN (Room Acoustics for Virtual ENvironments) under development. (Photo: Sönke Pelzer / Institut für Technische Akustik an der RWTH Aachen)

-

SoundLab is a prosthetic system more like the internet than an implant, and it lets a group of people hear impossible things. This ability has revolutionised some design practices already. For example, new performing arts spaces have a benchmarking stage where the architect, engineer, and client fly to a few important halls to compare them. Vienna’s Musikverein and Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw are often on the list. But how do you compare two rooms when you’ve travelled for a day between them, or listened to different music in each one, or sat in different seats?

SoundLab toggles between simulations of the same piece performed in dozens of halls in real-time. Doing this makes you doubt what anybody means by a “great” room, and forces project teams to find shared vocabulary for acoustic terms like warm and dry, presence and intimacy, while young designers can quickly develop their acoustic intuition. “Instead of having to take them to a hundred buildings, which might take five years, you can just spend a bit of time listening to this room”, explains Patel, “and tell me where it differs from what you expect”.

SoundLab is not limited to concert halls. Arup helped Michael Arad and Handel architects with the World Trade Center memorial, focusing on two problems: designing the soundscape as a visitor moves from Fulton street down to the memorial and into the museum, and making a cost-effective proposal for isolating the museum’s auditorium from subway noise. The disappearance of the city as noise is central to the power of the WTC memorial experience; you enter the plaza (after a surreal airport-security check) and feel transported. Arup built a 3D acoustic model to make sure this would happen. For the auditorium, a glance at the graphs might suggest that sonic isolation of both the room and building is required, but a perceptual investigation using auralisation can ask: “When do you know a train is a train?” What is audible is not the same as what is intrusive. -

Lev Bratishenko is a writer whose work has appeared in Abitare, Canadian Architect, Cabinet, Gizmodo, Icon, Maclean’s, Mark, Triple Canopy, and other publications. He lives in Montreal, where he covers classical music for the Montreal Gazette. In 2010 he curated the exhibition The Object is not Online at the Canadian Centre for Architecture.

yesyesyes.ca

![]() World Trade Center Memorial by Michael Arad of Handel Architects, who worked with landscape architects Peter Walker and Partners, and Arup. Snøhetta’s Memorial pavilion is behind. (Photo: Snøhetta)

World Trade Center Memorial by Michael Arad of Handel Architects, who worked with landscape architects Peter Walker and Partners, and Arup. Snøhetta’s Memorial pavilion is behind. (Photo: Snøhetta) Wave field synthesis is the newest technology in virtual acoustics. This system produces a large area of accurate 3D sound so you can move about in a space and it still sounds real. Soon, you could put yourself in a hamster ball with an Oculus Rift and “walk through” a design, listening to your footsteps change as you toggle between marble and wood. After this is accomplished, the next technical challenge will be a full sensory simulation with lighting that warms your face, and systems to replicate the instant feeling of opening a window.

High-end fantasy, maybe, but you can already run virtual acoustics software on a laptop. A team from the Institute of Technical Acoustics at RWTH Aachen University has produced a package for the SketchUp platform that claims near real-time auralisation capabilities: draw it and hear it. Will there be benefits beyond acoustics once this becomes part of the standard design toolkit? Patel thinks so. “You become better at designing spaces in general, because you are thinking about how people are sensing and perceiving space”. I -

DAVID BYRNE

• Playing the Building •

With his travelling installation Playing the Building, our favourite Talking Head – David Byrne – has managed to convert entire buildings into musical instruments. The chosen building’s latent symphonic qualities are activated by the keys of a vintage chapel organ, which tug specific cables rigged throughout the building to instigate wind, vibration, or physical contact on the architectural surfaces. The inherent resonant qualities of beams, pipes, and ducts emit melodic, enchanting, and often eerie sounds. Any visitor can step into the building and mess around on the keyboard. No piano lessons necessary.

So far Playing the Building has been shown four times: at Färgfabriken, Stockholm (2005); Battery Maritime Building, New York (2008); Roundhouse, London (2009); and Aria, Minneapolis (2012). (ew)Byrne at the Aria in Minneapolis, 2012. (Photo: Jake Armour, Armour Photography)

-

David Byrne is a Scottish-born musician living in the US. He is best known as the front-man of the Talking Heads from 1975-1991, a band inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2002. Byrne is a true multi-media artist, who has produced several solo albums and also worked with film, photography, text, and every musical genre under the sun. He has been awarded a Grammy, Oscar and a Golden Globe.

davidbyrne.com

Photo: Justin Ouellette, New York, 2008. Video courtesy David Byrne.

-

![]()

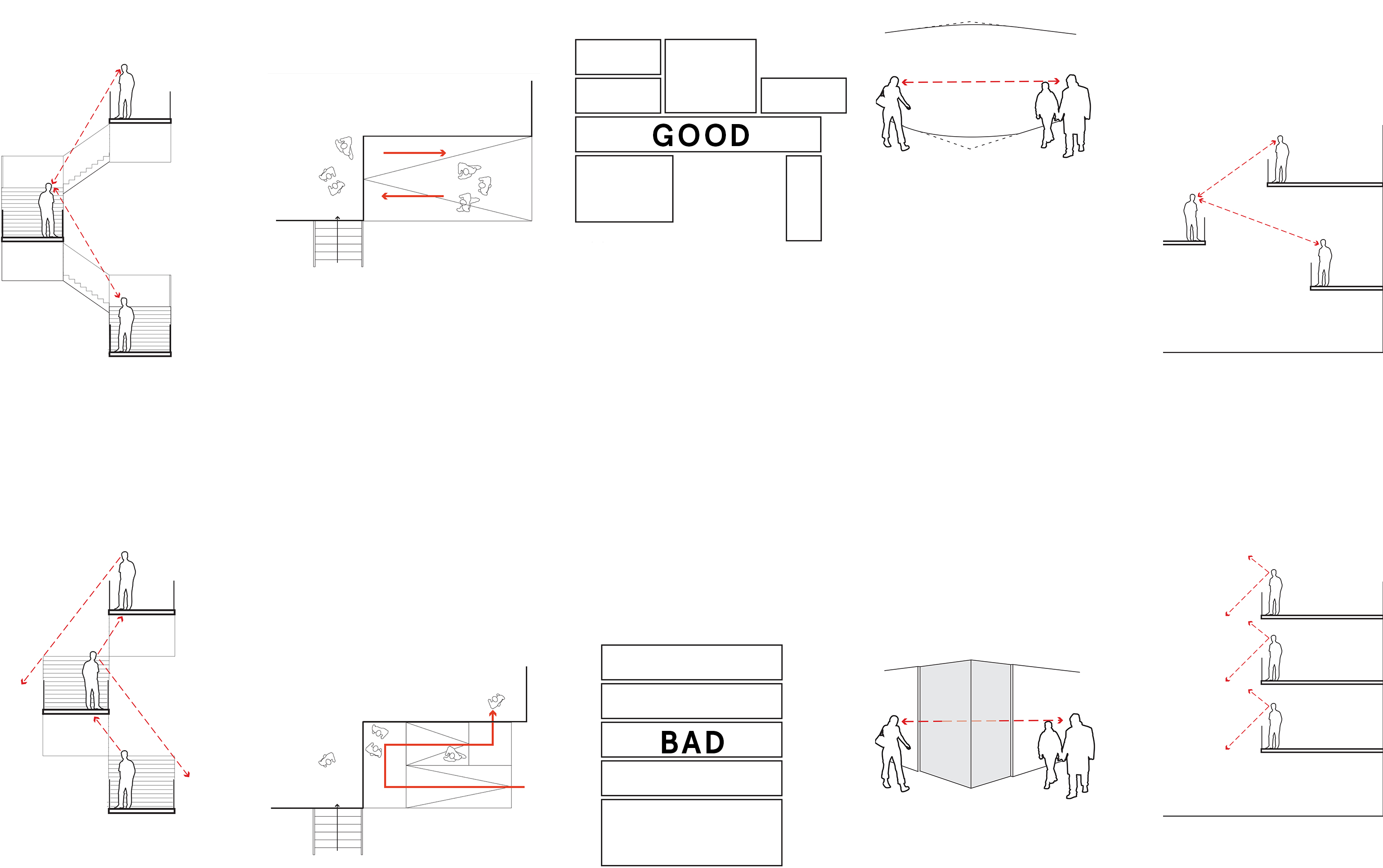

One wouldn’t necessarily assume that acoustics needed to be taken into consideration when designing architecture for the deaf. Yet acoustics constitute one of the five DeafSpace Guidelines, a code for designing accessible spaces co-developed over several years by US architect Hansel Bauman and many others. Since 1995 Bauman has been developing and testing these guidelines in close collaboration with the teachers and students at Gallaudet University for the deaf in Washington, DC. with input from several architecture firms.

-

Because deaf people are hyper-sensitive to vibration, and many wear cochlear implants that pick up ambient sounds, a loud air conditioning unit or a hallway echo that the hearing barely notice can cause discomfort or confusion for a deaf person. Minimising noise, however, is only part of the story, and the other DeafSpace guidelines address various ways of maximising visibility. Having a conversation in sign language, especially while walking, requires that two people have enough space between them to see each other’s hands; therefore interiors conducive to deaf communication need to have wide, open spaces with clear sightlines. Light balance and colour palette should also be carefully mitigated to reduce eye strain. In 2008 Gallaudet first implemented the DeafSpace Guidelines in the new James Lee Sorenson Language and Communication Centre building, a joint venture between SmithGroup and Kuhn Riddle Architects. The SLCC was a true testing ground; many promising-sounding ideas were less of a hit in real life. One experiment in rounded corners for visibility, for instance, resulted in an unexpected side effect: walkers tend to speed up and crash into each other when hugging a rounded wall.

After studying how users experienced the SLCC, Bauman and a university team planned the Living and Learning Residence Hall, a student dorm built in 2010 by LTL Architects, Quinn Evans Architects and Signal Construction.

![]()

![]()

Maximising visibility and minimising acoustic interference are the key aspects of DeafSpace. (Images: DangermondKeane Architecture; DeafSpace Design Guide © Hansel Bauman)

-

Hansel Bauman, Architect + Planner (HB / a+p) was established in July 2006 to address complex design challenges with an inclusive and considered approach to architecture and planning for higher education, scientific research, and community based projects.

Bauman has over twenty years of experience in planning and design of facilities for education, scientific research, industry and residential communities in the US, Europe and Asia. The majority of this experience is drawn from his work with large, national design and planning firms. He is currently Director of Campus Design and Planning at Gallaudet University.

![]()

This time glass corners, rather than rounded ones, were designed, large spaces prone to reverberation were carefully soundproofed, and a large multi-purpose room on the ground floor was subtly stepped according to the ground plane to allow full sightlines.

These subtle changes are low-tech, sustainable solutions that could truly improve any building. As Dave J. Lewis from LTL puts it, “DeafSpace takes the deaf experience and uses it as a way of challenging the perfunctory, normative expectations of architecture according to modernist understandings of efficiency, which prize time and economy at the cost of social interaction.” Here, efficiency is measured according to ease of communication – success determined via human experience. I (ew) -

![]()

Photo: Alexander Paul Brandes. Video courtesy Berlin Philharmoniker.

Symphony in Concrete

Hans Scharoun’s Philharmonie

![]()

-

Hans Scharoun (1893-1972) was born in Bremen, Germany and studied at Berlin’s Technical University (TU). His studies were interrupted in 1914, when he volunteered to fight in World War One. After the war he worked for Paul Kruchen in Breslau and designed the first exhibition of the expressionist group Die Brücke in East Prussia.

From 1925-32 he was a Professor for Architecture at the Breslau Academy for Arts and Crafts. He was also a member of Bruno Taut’s expressionist architects group the Glass Chain and later the Der Ring architectural collective. In the late 1920s, Scharoun was responsible for the development of the Siemensstadt housing estate in Berlin. Inspired by Hugo Haring’s theory of new building, he departed from rationalism and began to focus on the organisation of social living space and the flexible allocation of space and function.

He remained in Germany during the Nazi era and took up a professorship at the TU where he had studied in 1946. After the war he completed numerous buildings, the most notable of which was the Berlin Philharmonie. The German embassy in Brasilia was his only building outside Germany. His partner Edgar Wiesnewski took over the practice after his death and oversaw the completion of his later buildings, including the Deutsche Schiffartsmuseum (Maritime Museum), the theatre in Wolfsburg and the Staatsbibliothek (State Library) in Berlin.

Berlin’s Philharmonie, built between 1960 and 1963, is one of the most renowned concert halls in the world. Designed by Hans Scharoun, it is part of the Kulturforum, a complex of buildings which also includes his Staatsbibliothek (State Library) and Mies van der Rohe’s Neue Nationalgalerie. While considered a masterpiece of expressionist modernism, it is as free from power play, pomp and ostentation as a building of this size can get. The architect, a product of the Bauhaus generation, believed passionately in a democratic architecture for the community, developing the concept of a city landscape, which should grow from the bottom up, arising from the needs of the community. This principle of “organic building” as Scharoun called it, found favour in the period of reappraisal post-war, and the resulting commissions mean Scharoun is now considered one of the defining German architects of the twentieth century.

His design for the Berlin Philharmonie was based upon a simple but revolutionary premise: that the music should be at the centre. The rest of the building grew around it, from the inside out. The 2,442 seats of the main hall are arranged in a complex pattern of raked terraces all around the podium in what has become known as a “vineyard” formation. The combination of these terraces and the prominent diffusion reflector surfaces in wood, stone and fibreglass aid the acoustics, giving the impression of being inside some vast, earth-toned, 3D Cézanne landscape. The foyer wraps around the hall like a mould or negative of the space it encompasses. It is a maze of multilevel decks, bridges, steps, and parapets with round porthole-shapes in Scharoun’s trademark nautical style. Not what one would call a beautiful building to look at, it is visually too complex – the apparent jumble of planes and angles are hard work on the eye. But sit inside during a concert and the architecture springs into vibrant life as it fulfils its purpose: the unification of space, music and people. In this respect, the Philharmonie has to be one of the most absolute public buildings ever built. I (sl) -

![]()

Interview by Sophie Lovell

Photography by Jens Liebchen

Acoustic reflector panels on the ceiling of the Berlin Philharmonie Kammermusiksaal. (All photos © Jens Liebchen)

-

The Berlin Philharmonie is an architectural masterpiece famously conceived from the inside-out around the requirements of its acoustics. Designed by Hans Scharoun, the main 2,442 seater auditorium called the Großer Saal opened in 1963, but Scharoun died before the second, smaller chamber music hall, the Kammermusiksaal, was built. This had been designed in detail by his partner Edgar Wisniewski, who also completed the surrounding suite of public cultural buildings, the Kulturforum.

As is so often the case in these “man behind the throne” scenarios, Wisniewski’s input is rarely acknowledged in textbooks, yet much of the Philharmonie’s success as a building is down to him. He died in 2007, but just over ten years ago, Sophie Lovell, uncube’s editor-in-chief, got the chance to meet Wisniewski, then a tall, striking man in his mid-70s, at the Philharmonie. She talked to him about a working life devoted to translating Scharoun’s simple yet revolutionary ideas – sometimes technically nightmarish to realise – into buildings of world renown.

Dr. Wisniewski, you started your working life as Scharoun’s assistant, helping design the Berlin Philharmonie, but ended up completing and continuing his work yourself...

Yes, we worked together for 15 years until he died. During the latter part we were in partnership, which contractually means if one partner dies, the other carries on the work. And that’s what happened.

![]()

Edgar Wisniewski in the foyer of the Berlin Philharmonie in 2003.

-

When he died in 1972, I had all these projects, including the rest of the Kulturforum, to continue.

The site was still a bombed-out wasteland then – though 30 years earlier it had been the busiest city centre in Europe.

The final location, on the former Kemperplatz, is not far from where the old Philharmonie building had been before the war. During construction, the Berlin Wall came down. We stood here on the roof and watched the tanks rolling up and the barbed wire being laid. Some of the main workmen on the site had to come through the sewers to work every day from the eastern part of the city. The building was very close to the border, almost within firing range. Nobody knew what was going to happen next.

» There are over 2,400 seats in the main hall, yet none is more than 28 metres away from the stage. «

How did your partnership with Scharoun come about?

When I finished my studies at the Technical University in Berlin, Rügenberg, one of Scharoun’s assistants, recommended me for a post in his office that was available. Of course I knew who he was and had attended his lectures. I liked how he worked in an organic way: the form of his buildings developing from the inside out. Then the very first project that came up when I began working for him was the competition for the Philharmonie. It was very helpful that I was heavily involved with music. I was in a famous choir at the time, St. Hedwig’s Cathedral Choir, which the Philharmonic Orchestra under [Herbert von] Karajan played with.

-

Berlin Philharmonie

![]() Location: Berlin, Germany

Location: Berlin, Germany![]() Architect: Hans Scharoun, Edgar Wisniewski

Architect: Hans Scharoun, Edgar Wisniewski![]() Date: 1963

Date: 1963![]() Room volume: 26,000 m3

Room volume: 26,000 m3![]() Seating capacity: 2,440

Seating capacity: 2,440![]() Reverberation time (mid-frequency, occupied): 1.85 seconds

Reverberation time (mid-frequency, occupied): 1.85 secondsThe larger auditorium of the Philharmonie, The Großer Saal, showing how “music is in the middle”.

-

My knowledge and understanding of the repertoire helped form a good, trusting relationship with Karajan, who was the one that pushed the Philharmonie through. Karajan also told me once he’d originally wanted to be an architect.

So Karajan was a decisive factor in choosing and building Scharoun’s design?

Although the scheme had won first prize in the competition, there were intrigues: people wanting to hinder its construction from the start. The decision to build was won narrowly by a single vote, only after Karajan threatened to leave the orchestra – and Berlin – if it wasn’t built. His support was decisive.

Was this support because of Scharoun’s idea of putting the “music in the middle”?

The trust and understanding between us, Karajan and the musicians was very important because this idea of putting music, the orchestra, at the centre of the hall with everything else circled around it, was new – the Berlin Philharmonie was the first. Scharoun always said that it’s no coincidence that wherever improvised music is played, people immediately form a circle around it, and that this must be translatable to a concert hall. The whole design developed from that premise.

Was the design driven primarily by the acoustics?

Putting the music – the acoustics – in the centre had other important benefits too: Scharoun didn’t want any hierarchies. In the seating there are only slanting planes and stalls with no dress circle, apart from two galleries for special music performances, and there’s a single foyer for all. The idea of being up close to the action was also important. There are over 2,400 seats in the main hall, yet none is more than 28 metres away from the stage.

That’s what’s so special about this space: you are so close to the people making music. This works the other way too: when you stand on the podium you feel how close the audience is, how they demand the best from you.

-

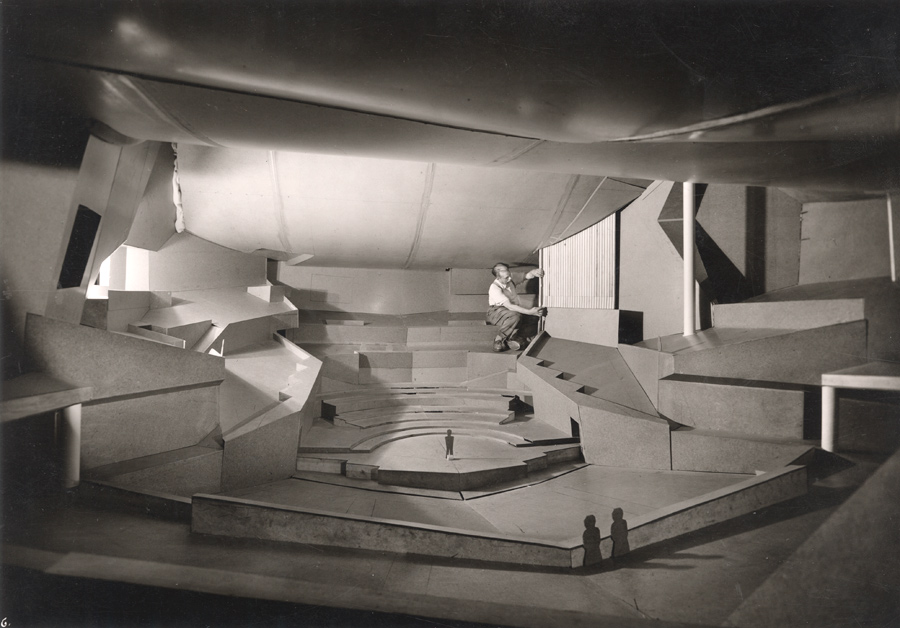

![]()

A 1:9 scale model of the main hall was built for testing the sound distribution. (Photo: Akademie der Künste, Berlin, Hans-Scharoun-Archiv, WV 222 F.135)» Scharoun always said it’s no coincidence that wherever improvised music is played, people immediately form a circle around it. «

![]() The design of the Kammermusiksaal, or chamber music hall, was developed by Wisniewski from a sketch of Scharoun’s.

The design of the Kammermusiksaal, or chamber music hall, was developed by Wisniewski from a sketch of Scharoun’s. -

I particularly like to sit in the choir seats behind the orchestra because you are so much inside it all. The whole floor, everything, vibrates there.

Do you think visiting musicians and orchestras look forward to playing here?

Since 1963, practically every great orchestra in the world has played here. But they do have to adjust acoustically. Many of them are used to playing in halls with a shoebox construction, with walls all around. Suddenly, here there is nothing – the flanking walls are relatively low, and some are angled, meaning part of the sound is reflected back to the orchestra so that the musicians can hear each other.

The reflectors in the ceiling are also specifically designed to stop the echoes from the high ceiling. A relatively long, two-second reverberation time in the full hall was originally requested, because that is what’s needed for the late Romantic pieces such as Brahms, Brückner, Mahler and Strauss, as is the tradition of the Berlin Philharmonic orchestra. The only way to get this reverberation is with a large volume, which is why the ceiling is 22 metres above the podium. But then it comes down in a convex sweep towards the audience, who comes up to meet it, like coming up the sides of a valley. Mrs. Scharoun said it looked like a vineyard.

I understand it was Lothar Cremer who worked out the acoustics. It must have been an intense collaboration.

Yes, the first thing he said was that it wouldn’t work! There was nothing to go on. Nobody had built a hall like this before. There were no lasers and computers for measuring like today. We built a big scale model at 1:9 that you could stand in, and they fired a type of acoustic pistol in there, recording the results with microphones.

And the Kammermusiksaal? You built that yourself based on a rough sketch from Scharoun.

I was not only deeply involved with music, I also studied musicology at the Technical University, with lectures from people like Hans Heinz Stuckenschmidt, one of Schönberg’s students.

-

Edgar Wisniewski (1930-2007) was a German architect. He was the son of an architect and pianist, and his interest in music and architecture was influenced by his parents’ house. He became the student and later partner of Hans Scharoun. After studying at the Berlin Technical University from 1950-1957, he was involved in creating the urban concept for the Kulturforum in Berlin. He was the artistic director for the Berlin Philharmonie, and oversaw the completion of the Staatsbibliothek (State Library) after his partner’s death. He later completed the state-commissioned Institute for Music Research, Musical Instrument Museum, and the Chamber Music Hall, based on a sketch by Scharoun.

I’d learnt about the whole development of new music and was able to bring this to the design of the Kammermusiksaal, and it was Scharoun’s wish that I do – he was very open. He made just one sketch of it: not so much a design as an agreement that we make a centrally oriented space. Cremer said it was acoustically more complicated to build than the main hall, but when it was finished we didn’t have to make any acoustic adjustments at all.

How much of the Philharmonie is you and how much is Scharoun?

That’s something I wouldn’t even discuss in private! Many changes had to be made to the original design, to the staircases, the foyer, and so on. I designed a lot in the building. Even the gold aluminium façade is mine.

Was it a burden carrying on Scharoun’s legacy?

Scharoun’s and my own achievements are inextricably bound. From the initial planning of the Philharmonie, I simply moved on to the other big building projects of the Kulturforum. They represent more than 30 years of continual work. I never perceived the work as a burden, more a challenge.

Do you see yourself as having lived in his shadow professionally? His name often only gets mentioned in relation to the Kulturforum ensemble.

Planning the four main buildings of the Kulturforum: the Philharmonie, the Staatsbibliothek, the Staatliche Institut für Musikforschung with the Musikinstrumenten Museum, and the Kammermusiksaal has been so fulfilling. I perceive Scharoun’s shadow as inspiring, not obliterating. He only lived to see the Philharmonie, but I, on the other hand, can look at the four buildings, remember the battles fought to build them and experience them now, today, filled with music. Any feelings about shadows evaporate. I

-

![]()

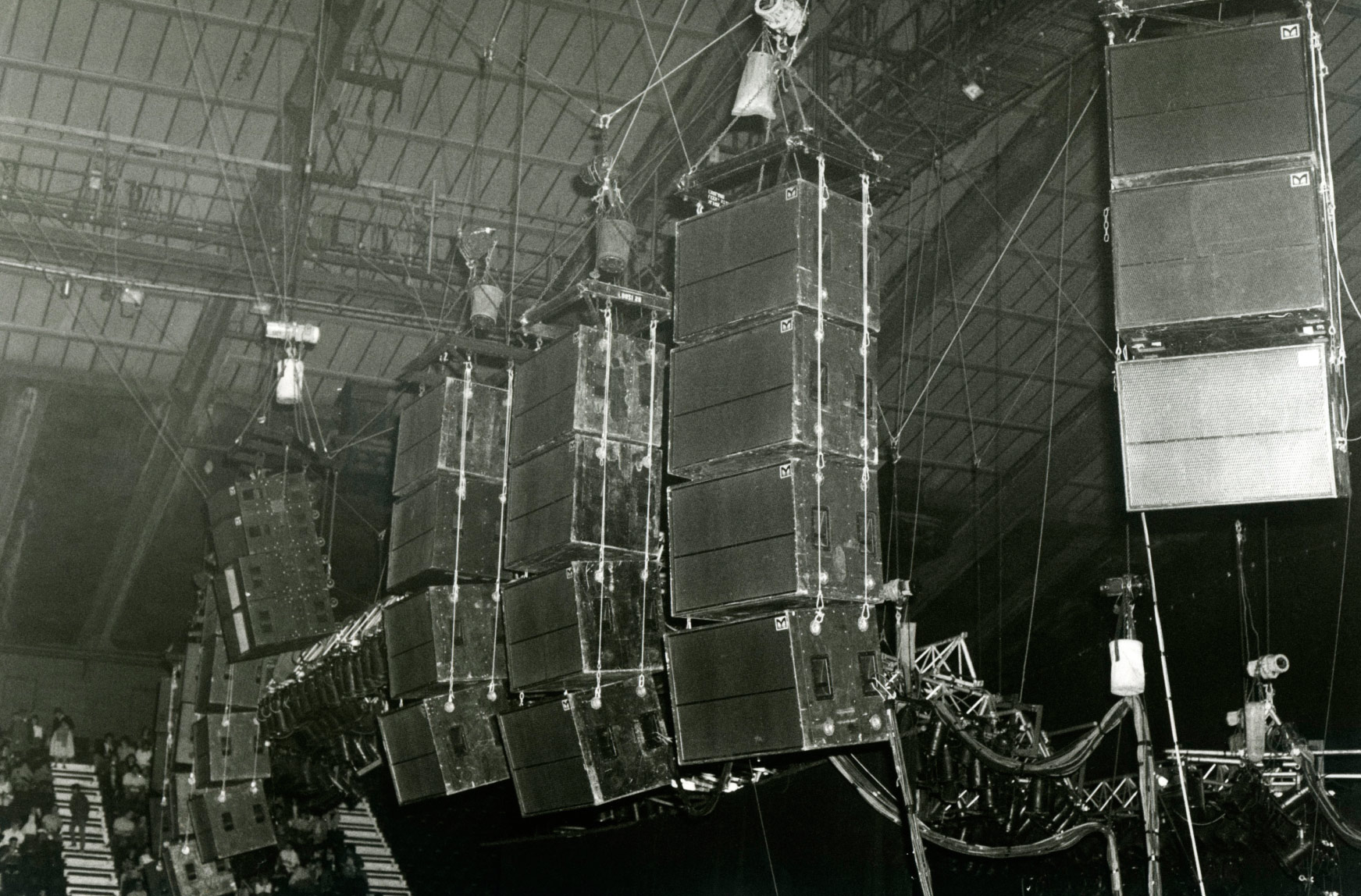

Play it Loud

Sound systems for supergroups

The 1970s saw the rise of giant concerts, big sounds and supergroups. Rock, pop and disco were flourishing at the time, and with them the technology of the sound system. You did not just hear the music any more, you “experienced” it. The London-based firm Martin Audio, founded in 1971, was one of the pioneers of the live concert sound system and was responsible for manufacturing live performance loudspeakers for bands such as Pink Floyd, the Who and Supertramp to play to larger audiences and be heard properly for the first time.

RS1200 sound system, designed by Martin Audio in the 1980s. (All photos courtesy Martin Audio)

-

Aside from the quality of the performance, a great deal of the quality of the physical experience of attending a live concert is dependent upon what’s going on with the huge stacks of black boxes placed strategically around the performance space. The science behind sound systems goes way beyond simply plugging in amplifying music across the venue. Whether before a concert or in a nightclub, sound technicians need to analyse the size and shape of the available space, relate this to its sound pressure, and then measure and calculate how the sound can best be dissipated in order to be heard coherently and precisely by the audience.

There is also the question of how “big” the sound can safely be: as the sound level in a venue or performance space increases, the sound pressure in the room elevates along with it – up to a point where the room is no longer able to disperse the energy – and things, specifically eardrums, start to get damaged.

Martin Audio sound system for Dire Straits concert at Juventus Stadium, 1981.

-

The legendary Pink Floyd concert at Earls Court, London in 1973 featured a Martin Audio 7000W system.

By additionally mounting acoustic panels on the walls to release the energy across the floor space in a thermo-dynamic transfer, it’s possible to reduce the effect of white noise and achieve higher sound quality without losing the feeling of “loud”. Delivering what Martin Audio call “dynamic, full frequency sound” to an increasingly discerning generation of habitual headphone-wearers is an evolving task that involves a great deal of research and development – but unlike other rock dinosaurs of the 1970s, Martin Audio is not showing any signs of fading away. I (ltv)

-

Yuri Suzuki is a Japanese sound artist, designer and electronic musician who produces work exploring the realms of sound between 1999 and 2005 he worked for the Japanese art project Maywa Denki after which he studied at the Royal College of Art. He has completed projects for Yamaha and Moritz Waldemeyer and in 2008 he opened his own London-based studio. In 2013 Suzuki was appointed as a tutor in the Product Design department at RCA, and became an associate for Disney, Teenage Engineering, and the New Radiophonic Workshop. In the same year he set up a consulting firm called Yuri Suzuki Creative Lab.

![]()

Image and video courtesy Disney Research

YURI SUZUKI

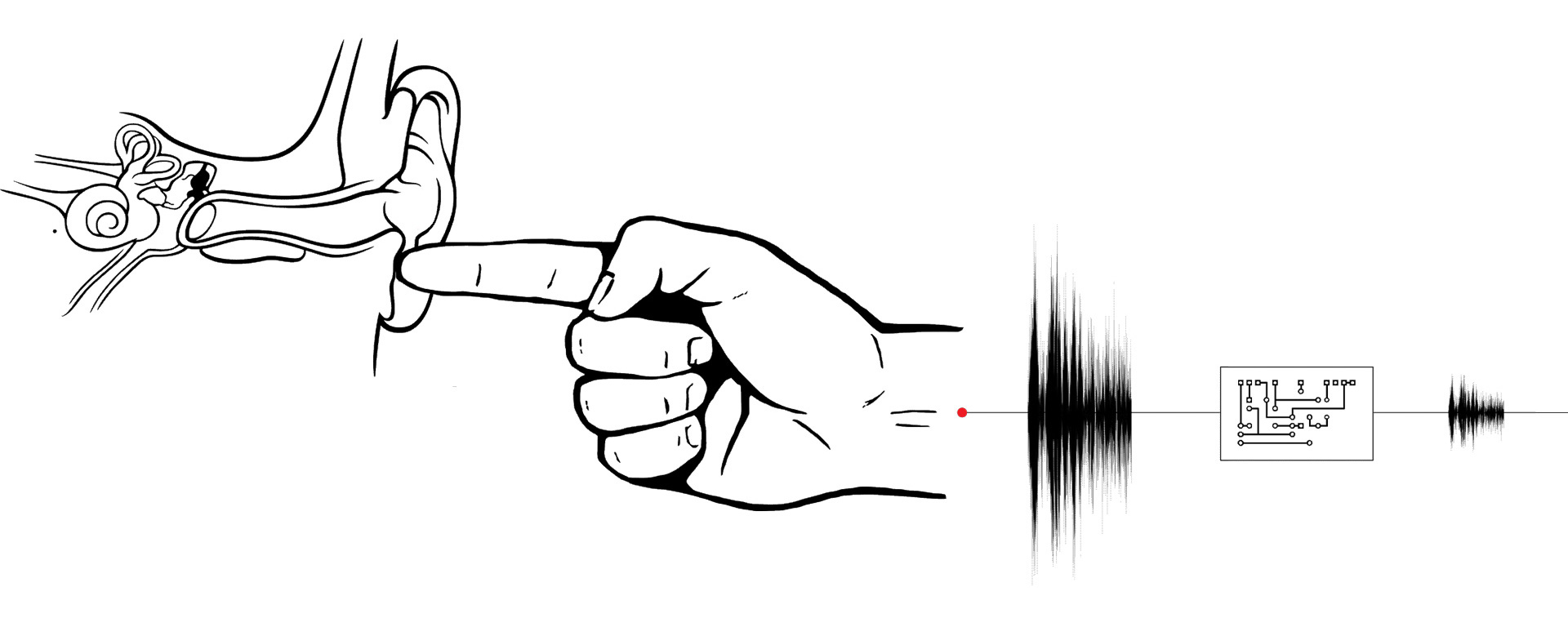

• Ishin-Den-Shin •

Remember your childhood fantasies of telepathic communication? This installation by the multitalented Yuri Suzuki is as close as you’re likely to get to the experience. In Ishin-Den-Shin, (created in collaboration with Oliver Bau and Ivan Poupyrev for Disney Research) a modified microphone translates a speaker’s voice into an inaudible signal. Using the body as a broadcasting medium, the recording can then be transmitted via touch – say, by putting your finger to a friend’s ear. The message ecipient then hears the words spoken into the microphone as if they were being whispered. The work’s title fittingly refers to a Japanese term for an unspoken yet mutually understood idea. I (ew)

![]()

![]()

-

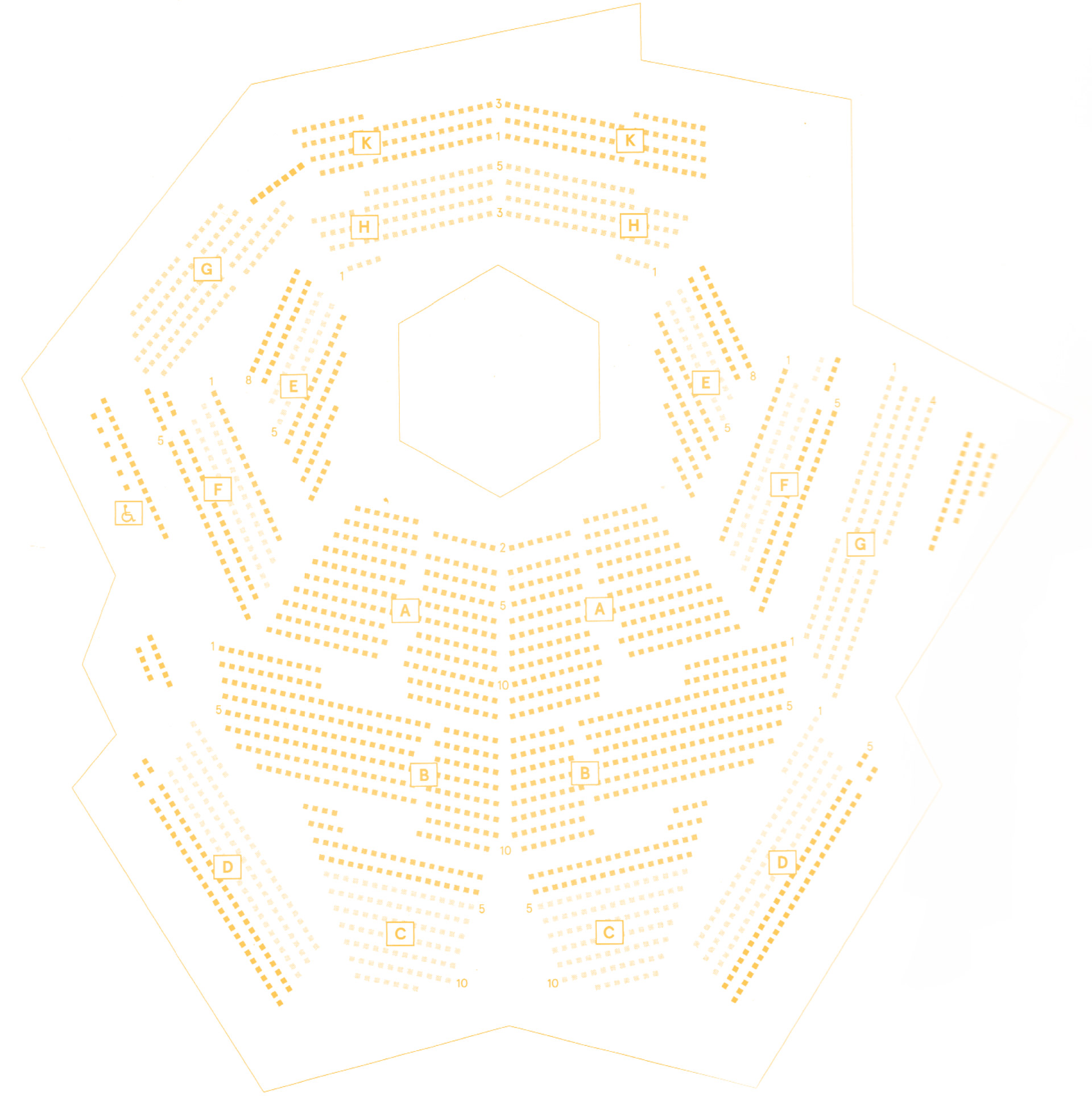

![]()

Music Boxes

Vredenberg Concert Hall in Utrecht

The Dutch city of Utrecht is currently undergoing a massive inner city redevelopment that involves revamping the ruthless modernisation that the historical city was subjected to in the 1960s and 1970s. Today the area – once a playground for progressive urban planners – is considered an eyesore and has been largely demolished. But in an example of adaptation and survival, explains Thomas Dieben here, the Muziekcentrum Vredenburg, a 1,700-seat concert hall by Dutch architect Herman Hertzberger, has remained, albeit in a considerably altered form. And who is responsible for its 2014 radical redesign? The very practice that designed it in the first place.

The 1978 Vredenburg Music Hall was an experiment in functionality and space, renowned for its acoustic qualities. (Image: Architectuurstudio HH)

-

![]()

Photo: Architectuurstudio HH![]()

Photo: Juri Hiensch / Tivoli VredenburgThe original project brief was complex and progressive: to remove all musical boundaries and leave a platform for the hybrid experimental musical expressions that were thriving in Utrecht in the 1960s. In the final building, completed in 1978, Hertzberger elaborated on this by eliminating spatial thresholds, allowing shoppers and pedestrians to be confronted with music. Thus the foyers, hallways and the central music hall were like streets and alleys in a continuous public landscape. The main hall became an acoustic work of art where the innovative, concentric layout – with its steep, intimate connection between seat and stage – functioned together with a human-scale design, such as the high-backed couch-like collective seating designed to function acoustically like “hands behind your ears”.

Patrick Fransen, project architect of the new Tivoli Vredenburg, praises the meticulous way of designing back then: “This was an age in which functionality and acoustics were designed with a sharp gut feeling and a few simple formulas – no computers involved”.

Fransen’s task was to rethink his master’s work, with Herman Hertzberger himself – still actively involved in his office at age 81 – as supervisor. Despite the generation gap between both projects, the same main theme is addressed: a combination of diverse musical expressions in a single building. This time, however, instead of one space accommodating many sub-scenes, all organisational parties involved demanded independence in their use and identity.

-

The 2014 radical redesign removed parts of the building and added three new auditoria in a new building in front. The original auditorium remains as the main stage and was redesigned by Hertzberger himself. He also chose the architects to design the three new “music boxes”. (Image & gif: Architectuurstudio HH)

![]()

-

Thomas Dieben is an Amsterdam-based designer, who, after studying at the TU Delft and working in Paris, founded denieuwegeneratie, a young design studio focusing on urban culture and the public interior.

Herman Hertzberger (1932) can be seen as the most important representative of Dutch structuralism and brutalism in the second half of the twentieth century. Closely connected to Aldo van Eck, he made his name with the Montessori School in Delft, the Centraal Beheer office and the Vredenburg Music Hall projects.

His designs evolved further throughout the 1980s and 1990s, but still kept a clear focus on human-scale design. Herzberger has been actively involved in architectural education, and produced a series of publications, which have formed the basis for a generation of designers and teaching at various European universities. Still active in his office at age 81, he received a Riba Gold Medal in 2012 recognising his role in modern architecture.

ahh.nl

The original project brief was complex and progressive: to remove all musical boundaries and leave a platform for the hybrid experimental musical expressions that were thriving in Utrecht in the 1960s. In the final building, completed in 1978, Hertzberger elaborated on this by eliminating spatial thresholds, allowing shoppers and pedestrians to be confronted with music. Thus the foyers, hallways and the central music hall were like streets and alleys in a continuous public landscape. The main hall became an acoustic work of art where the innovative, concentric layout – with its steep, intimate connection between seat and stage – functioned together with a human-scale design, such as the high-backed couch-like collective seating designed to function acoustically like “hands behind your ears”.

Patrick Fransen, project architect of the new Tivoli Vredenburg, praises the meticulous way of designing back then: “This was an age in which functionality and acoustics were designed with a sharp gut feeling and a few simple formulas – no computers involved”. Fransen’s task was to rethink his master’s work, with Herman Hertzberger himself – still actively involved in his office at age 81 – as supervisor. Despite the generation gap between both projects, the same main theme is addressed: a combination of diverse musical expressions in a single building. This time, however, instead of one space accommodating many sub-scenes, all organisational parties involved demanded independence in their use and identity. I (Thomas Dieben)

All auditoriums are visible in the large, open foyer of the Tivoli, making orientation in the building easy – like different music boxes hanging in space. (Image: Juri Hiensch / Tivoli Vredenburg)

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

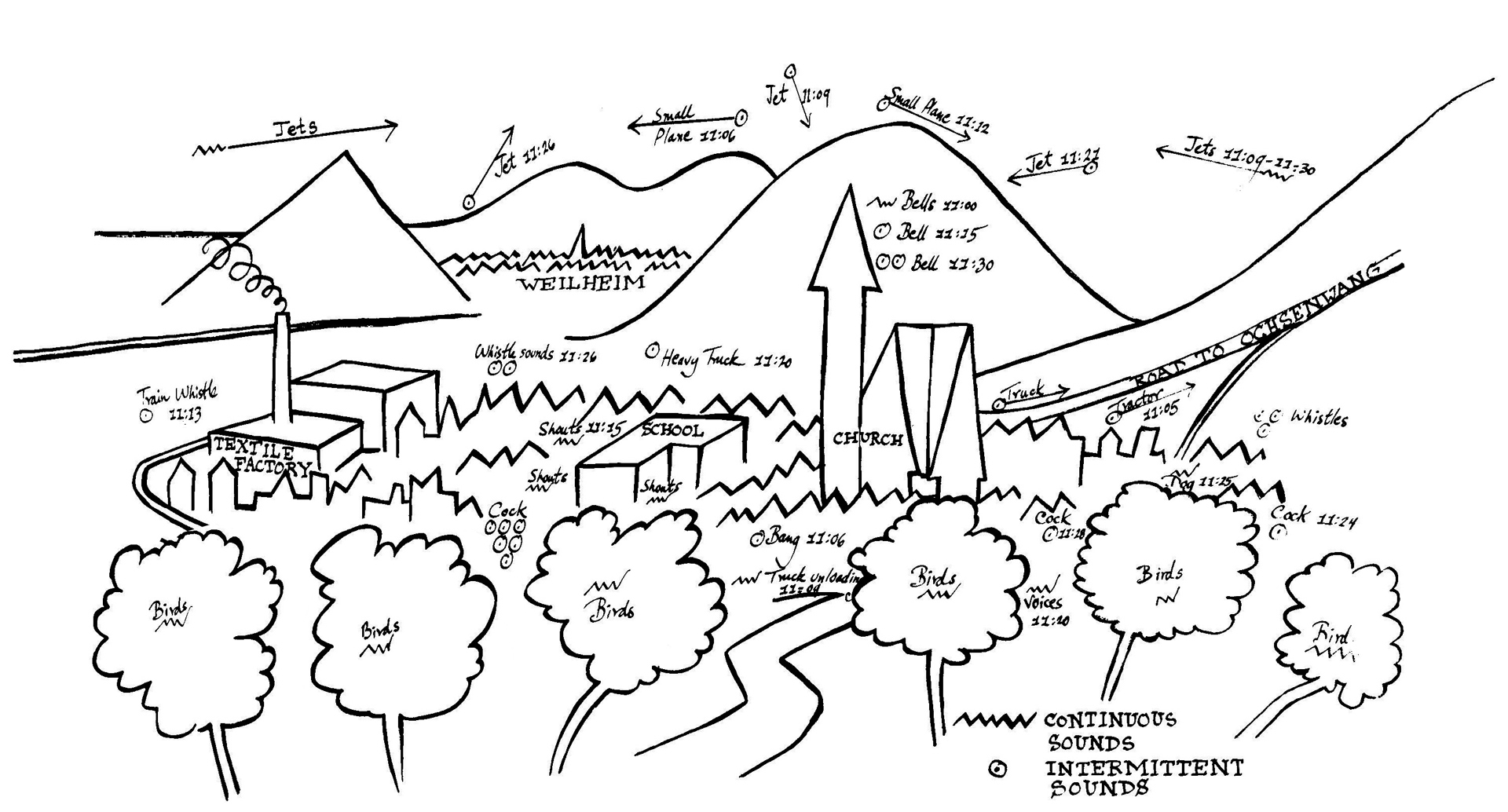

Planning urban soundscapes

by Melonie Bayl-Smith

Sketch sound analysis of Bissingen Village, Germany, from “Five Village Soundscapes”, No. 4, The Music of the Environment Series, edited by R. Murray Schafer (reproduced by permission of the World Soundscape Project, Simon Fraser University).

-

The sonic qualities of cities and urban spaces are the subject of growing research in “urban sound planning”, which is increasingly being used to inform the design of new cities. However, awareness of these qualities and their positive and negative aspects is nothing new, having been the focus of works by artists, audio documentary makers, sound historians, composers, architects and urbanists for several decades.

Canadian artist and academic R. Murray Schafer, a key figure in the field of acoustic ecology and a founder of the World Soundscape Project (WSP), coined the term “soundscape” for his work on noise pollution in the late 1960s and early 1970s. From such negative beginnings, the development of studies, artworks and recordings of soundscapes and the utilisation of “found sounds” from field recordings have all contributed to a significant body of investigations benefitting artists, spatial practitioners and communities alike.

Whilst the recording or collection of found sounds originated in the biophonic documentary recordings of natural environments, this activity moved indoors some time ago. Practitioners such as Francisco Lopez have recorded the sounds of buildings derelict or otherwise, overlaying and massaging these sounds into controlled recordings suitable for aurally bombarding audiences in blacked-out listening spaces.

Other artists, such as Janet Cardiff, have deployed high-end technology and spatial manipulation to place participants and observers into the soundscape of a specific place (both real or abstract) regardless of their actual location. For example, Cardiff created her work The Forty Part Motet from a version of one of the finest examples of early music, loosened from its physical demands (five choirs, forty singers, a decent choir stand) by the use of forty carefully placed speakers. The simultaneous music and acoustic environment converts the selected physical location into a sacred chapel space – sound as the manipulator and creator of architecture, both sited and siteless.

More recently, the collection of found sounds and haptic soundscapes has moved into the fetishisation of “geophony”, with the increasingly available means of documenting urban spaces through the sounds that locate them – physically, historically, culturally.

-

Melonie Bayl-Smith is an architect, musician and educator from Sydney, Australia. An adjunct professor at UTS School of Architecture, her project, studio and research collaborators span institutions and practices across Australia, Europe and the UK. She writes for AR Asia Pacific, AA, Artichoke, Cyclic Defrost, and contextfreesound amongst other publications.

![]()

Video: “Soundscapes”, stereosoundagency.com

Cities such as Melbourne, London and Montreal now have online city soundmaps readily accessed for use by the public, featuring “pins” that indicate the location of a particular environment and the activities typical of that recording site. The value of these maps is variable – recordings range from the mundane to those of real social significance, including lost sounds inherently reliant on human interaction, such as trading or manufacturing activities.

With the danger of standardised urban sound planning resulting in a type of aural hygiene in safe and healthy cities, the work of sound artists, composers and collectors could become increasingly valuable, as they plunder public places for elusive and unexpected sounds, then hack and covert the acoustics of urban spaces. Architects and designers, rather than looking to homogenise the city and segregate soundscapes, might instead embrace the artist’s exploration and trapping of the sometimes indeterminate, sometimes exceptional sounds caught between buildings and walls. In turn, both fragments and slabs of soundscapes could better convey and relate the social significance of human activities, channelling these as the basis for planning better cities. I

-

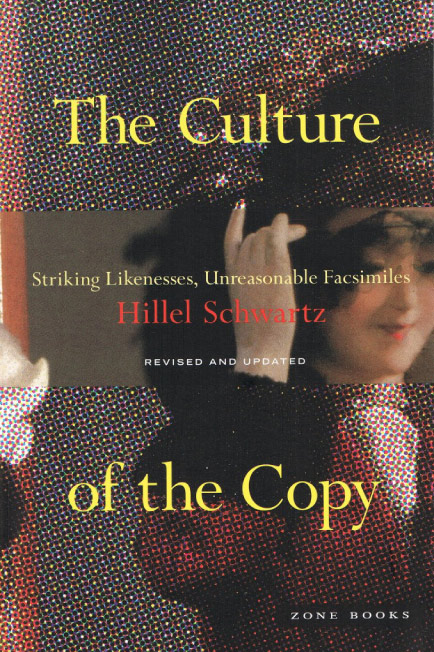

The Culture of the Copy: Striking Likenesses, Unreasonable Facsimiles

(newly revised and updated edition)

Hillel Schwartz

The MIT Press

Paperback, 568 pp., 6 x 9 in.

ISBN: 9780942299359

mitpress.mit.eduCarson Chan is an architecture curator and writer. He co-curated the 4th Marrakech Biennale (2012), and was Executive Curator for the Biennial of the Americas (2013). He is currently pursuing a PhD in Architecture at Princeton University.

![]()

For our third guest-reviewed bookmarked section, we’ve asked curator/writer extraordinaire Carson Chan to choose three tomes exemplifying his taste in text – one very fat, one deliciously savoury, and one we will describe only as “interesting”.

The fact that we’re able to reproduce most things with unprecedented speed today doesn’t make the copy contemporary. This revised and updated edition of a book on the concept of the copy by poet and cultural historian Hillel Schwartz brings us back to ancient Greece before getting to photocopiers and the Internet. Schwartz is known both for his translations of Korean poetry and his writing on everything from the politics of sound, fat, millenarianism, and French prophets.

Since the book’s first printing almost 20 years ago, it has itself appeared as pirated PDF copies on online file sharing sites – but reading this physical re-issue (especially if you’ve read the first edition), brings the subtle and beautiful meaning of the copy home. Objecthood aside, read it for Schwartz’s erudite prose, particularly if you’re a wordsmith.

![]()

-

Consider the Oyster

MFK Fisher

North Point Press

Paperback, 96 pp., 7.8 x 5 in.

ISBN-13: 978-0865473355

![]()

Both WH Auden and John Updike have praised Mary Frances Kennedy Fisher’s prose as second to none. The mid-century American food writer has an easy clip to her words, and she describes food with the same pearly efficiency we recognise in Hemingway. In homage David Foster Wallace named both his 2004 essay and 2005 book Consider the Lobster, after this 1941 volume of hers. Fisher’s original tome, peppered with recipes throughout, is a series of her memories and ideas related to oysters, recounted as if told by the doyenne herself at a cocktail party. We learn that her mother loved the oyster bread served at her school dormitory in the 1890s, that the best oysters she ever ate were prepared at an inn in France, and that Cicero nourished his eloquence with hundreds of oysters each day.

![]()

-

Our Aesthetic Categories: Zany, Cute, Interesting

Sianne Ngai

Harvard University Press,

Hardcover, 344 pp., 9.3 x 6.3 in.

ISBN-13: 978-0674046580

hup.harvard.edu

![]()

In the information age, the more we’re exposed to, the more we’re asked to opine upon what we see. Short of actually coming up with a response, we label many things as simply “interesting”. Stanford English Professor Sianne Ngai’s book seeks to figure out what it is we mean when we use this non-response response. Her method is thorough and academic, beginning with the word’s usage in literature through Kant’s Critique of Judgment and JL Austin’s How to do Things with Words. The same analysis is given to other words of “weak aesthetic judgment” like “cute” and “zany” – you’ll have to read the book to find out why the latter word is included in the mix. I

![]()

-

![]()

-

![]()

Issue No. 22:

May 28th, 2014

Photo: Gigi Cifali, "Chadderton Baths, Oldham", 1937-2007.

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»I hate vacations. If you can build buildings, why sit on the beach?«

Philip Johnson

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents

The design of the Kammermusiksaal, or chamber music hall, was developed by Wisniewski from a sketch of Scharoun’s.

The design of the Kammermusiksaal, or chamber music hall, was developed by Wisniewski from a sketch of Scharoun’s.