-

Magazine No. 24

Hans Hollein

-

No. 24 - Hans Hollein

-

page 02

Cover

Hans Hollein

-

page 03

Editorial

Hans Hollein

-

page 04 - 10

Everything is Architecture

Excerpts from Hans Hollein’s 1968 Manifesto

-

page 11 - 12

Vulcania

-

page 14 - 17

Total Retail

Hans Hollein’s Commercial Spaces

-

page 18 - 20

Head Space

Walter Pichler, Hans Hollein’s radical collaborator

-

page 21 - 23

Zumtobel Group Award

Part 2

-

page 24 - 33

Hollein

Wilfried Kuehn and Marlies Wirth on Hollein's Legacy

-

page 34 - 38

Shape Shifter

Hollein’s Design Objects

-

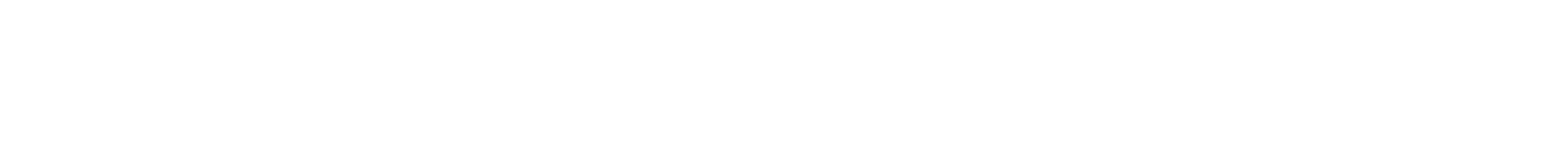

page 39 - 44

A Piece of Cake

Hans Hollein’s Museum for Modern Art in Frankfurt am Main

-

page 45

Mobile Office

Experiments in invisible, carry-on architecture

-

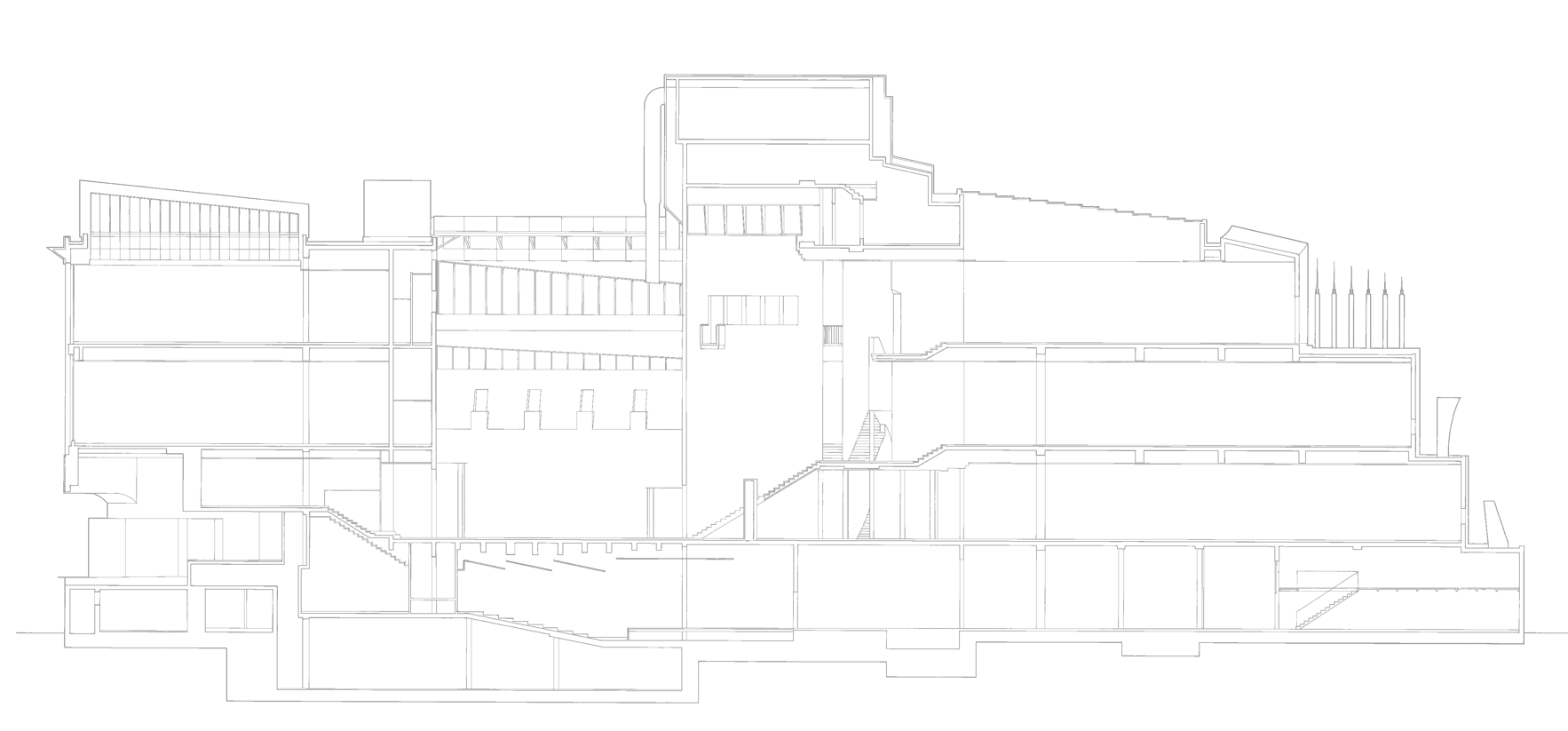

page 46 - 47

The Museum of Glass and Ceramics

-

page 48 - 51

The Great Exhibitionist

Hollein as designer-curator

-

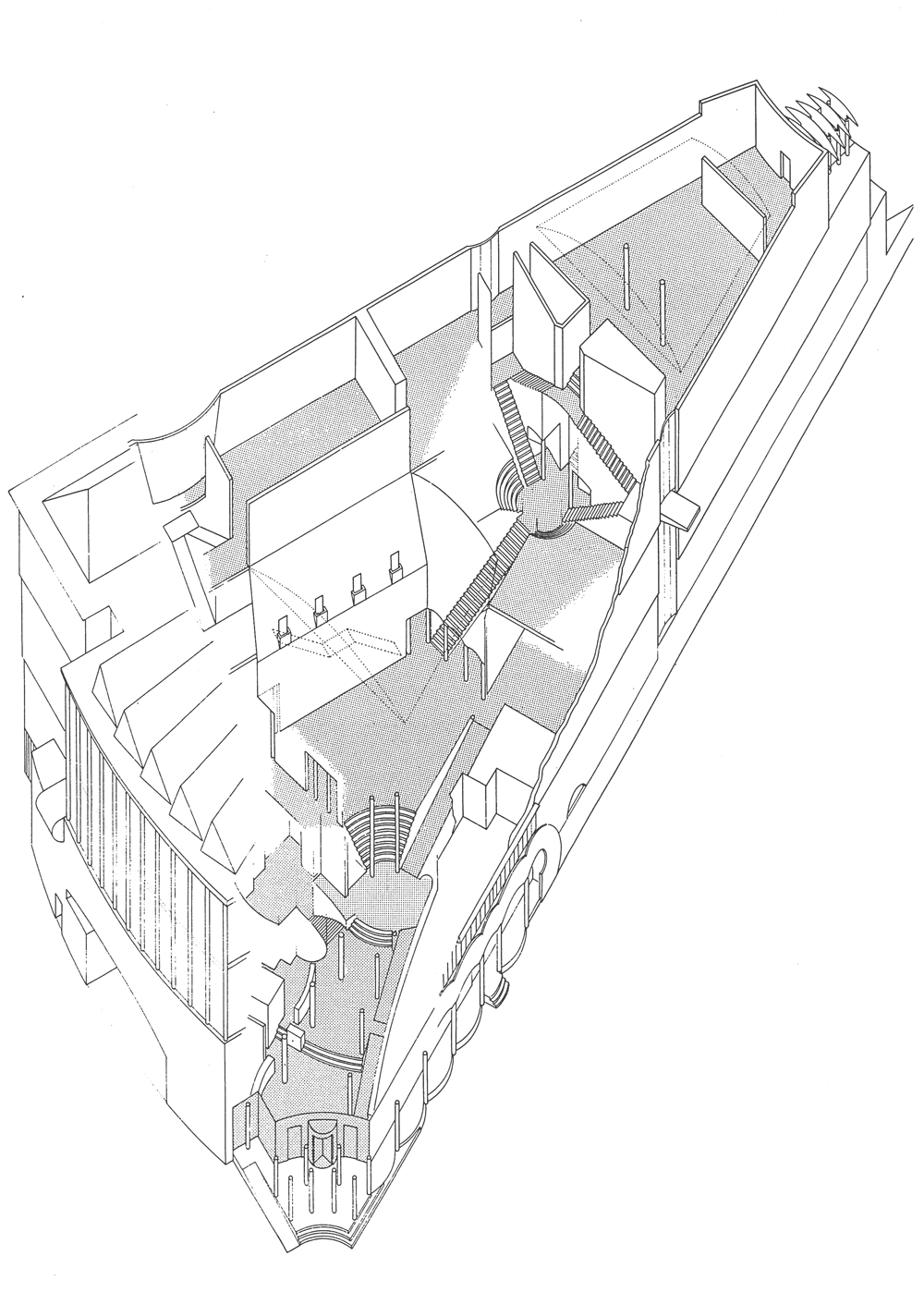

page 52 - 53

The Abteiberg Museum

-

page 54

SBF Tower

-

page 55

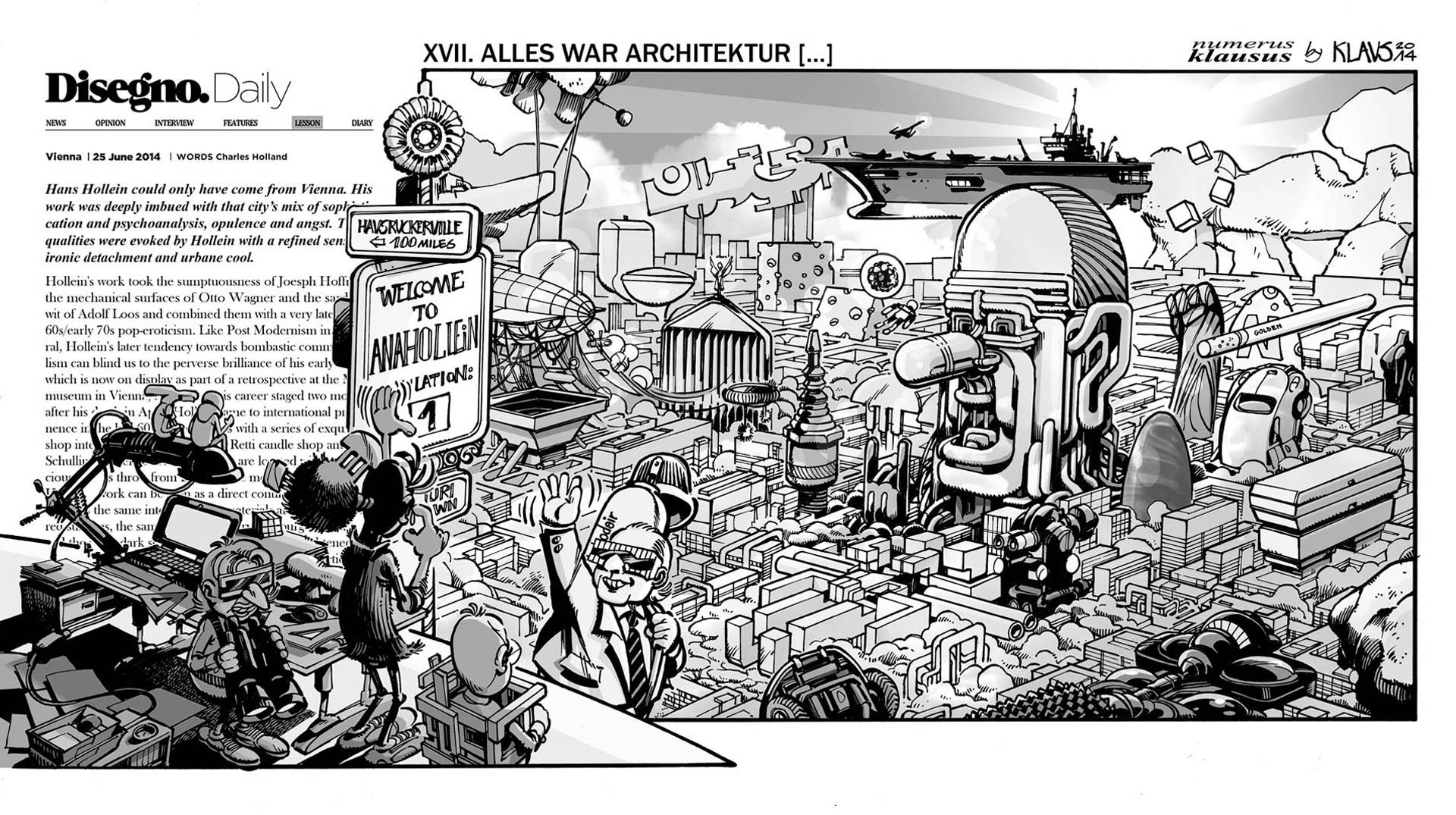

Klaustoon

XVII. Alles war Architektur

-

page 56

Next

Soft Machines

-

-

uncube's editors are Sophie Lovell (Art Director, Editor-in-Chief), Florian Heilmeyer, Rob Wilson and Elvia Wilk; editorial assistance: Susie S. Lee and Leigh Theodore Vlassis; graphic design: Lena Giovanazzi; graphics assistance: Madalena Guerra. uncube is based in Berlin and is published by BauNetz, Germany's most-read online magazine covering architecture in a thoughtful way since 1996.

![]()

![]()

![]()

This month uncube takes a Po-Mo moment to celebrate the work of Hans Hollein (1934-2014). An Austrian architecture avant-gardist and multi-talent who denounced buildings and then went on to design many of them, along with furniture, interiors, sets and exhibitions – but always from the inside out.

Join us on a journey into the interior, to beauty on the inside, where Everything Is Architecture.

Special thanks to MAK Vienna, Hans Hollein & Partner and the Hollein Archive for all their support.

Cover illustration: Madalena Boavida Guerra and Lena Giovanazzi, photo courtesy Hans Hollein archive. This page: Lena Giovanazzi

-

![]()

Excerpts from Hans Hollein’s 1968 ManifestoHans Hollein, "Superstructure above Manhattan", 1963. (Image © Hans Hollein Archive)

-

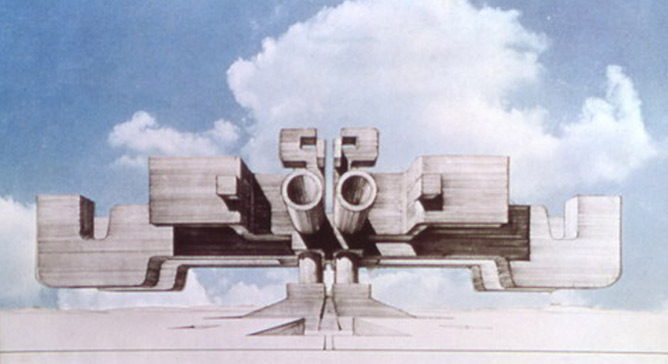

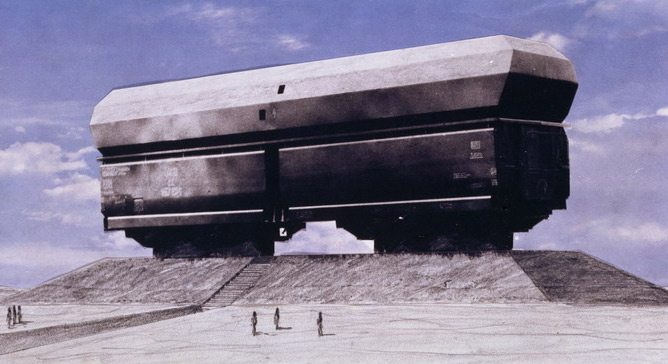

In 1962 Hans Hollein and Walter Pichler wrote a manifesto called “Absolute Architecture” in which they declared that “architecture was a ritualistic expression of pure, elemental will and sublime purposelessness”. In the 1968 (1/2) edition of the Bau journal Hollein went on to write and illustrated his own 30-page manifesto for a new generation of architects and designers in which he declared: "Everything is Architecture".

![]()

Miss Radial Age, 1960s advertisng campaign. (Image courtesy Michelin)

-

The extension of the human sphere and

the means of its determination go far

beyond a built statement. Today

everything becomes architecture.

“Architecture” is just one of many

means, is just one possibility.

Man creates artificial conditions.

this is architecture

Physically and psychically man repeats,

transforms, expands his physical and

psychical sphere. He determines

“environment” in its widest sense.

According to his needs and wishes he

uses the means necessary to satisfy

these needs and to fulfil these dreams.

He expands his body and his mind.

He communicates.![]()

alles ist architektur

![]()

Hans Hollein “Communication-interchange of a City”, 1963; Hans Hollein, “Monument for the Victims of the Holocaust”, 1967. (© Hans Hollein archive)

-

![]()

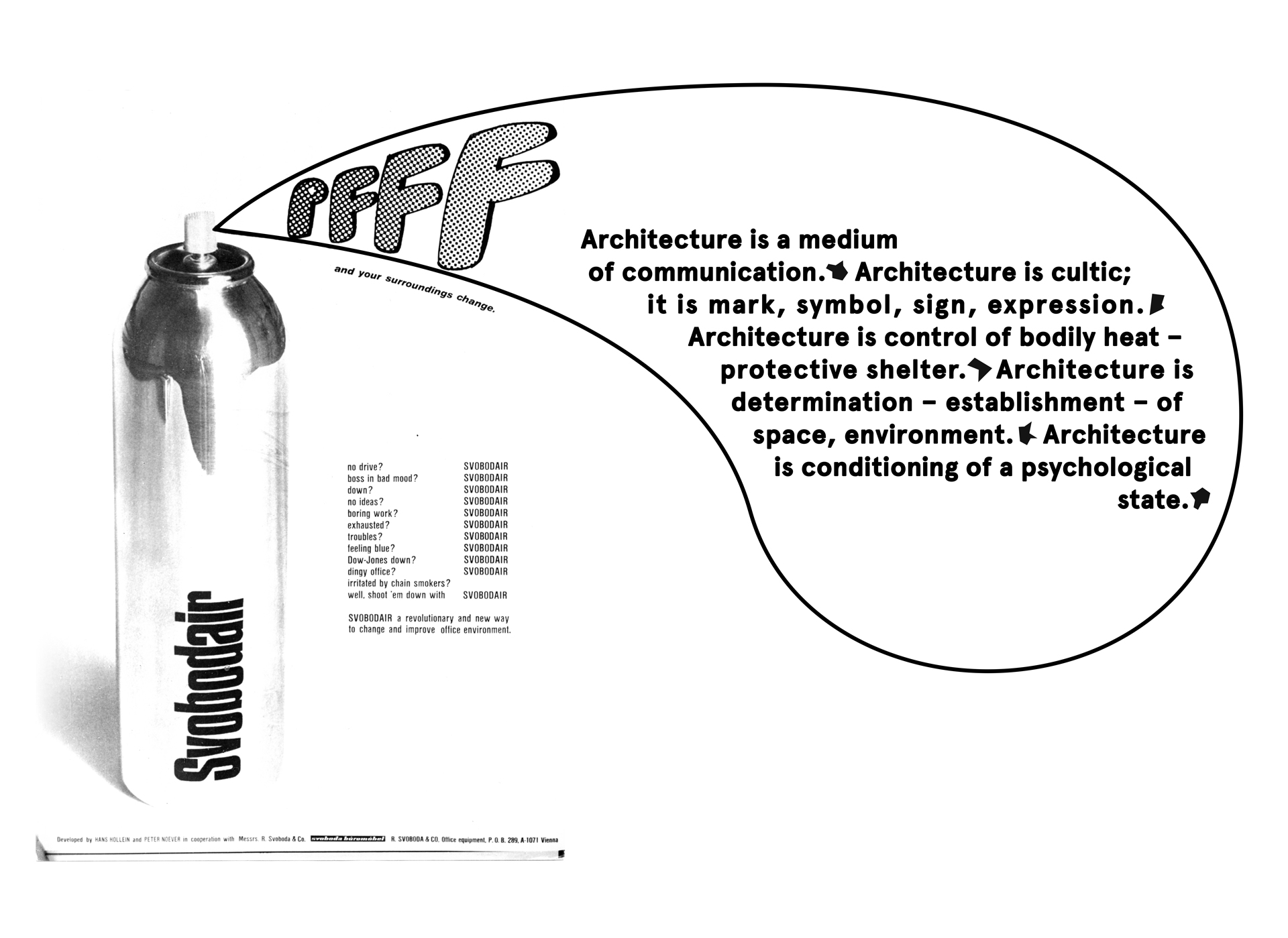

Hans Hollein and Peter Noever, “Svobodair” environment spray, 1968. (Courtesy Hans Hollein archive, © Generali Fondation)

-

Hans Hollein: “Neue Residenz Schloss Schrattenberg”, 1966. (Image © Hans Hollen archive)

alles ist architeKtur

-

Architects must cease to think

only in terms of buildings.

After shedding any necessity

for a physical![]() shelter at all,

shelter at all,

a new freedom can be sensed.

Man will now finally be the centre

of the creation of an individual

environment.Hans Hollein, “Non-physical environment”, 1967. (Courtesy Hans Hollein archive, © Atelier Hans Hollein)

-

All are architects

Everything is architecture

A true architecture

of our time will have

to redefine itself and

expand its means.Many areas outside

traditional building

will enter the realm

of architecture,as architecture

and "architects"

will have to enter

new fields.![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Anulf Rainer, “Überbauungen de Votivkirche”, 1962. From Han Hollein's “Alles ist Architektur” © Hans Hollein Archive.

![]()

![]()

-

![]()

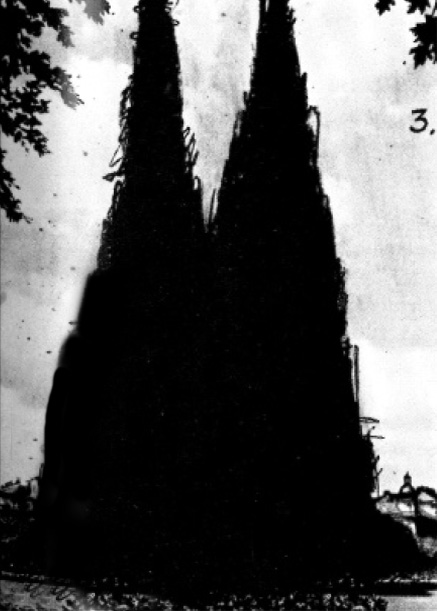

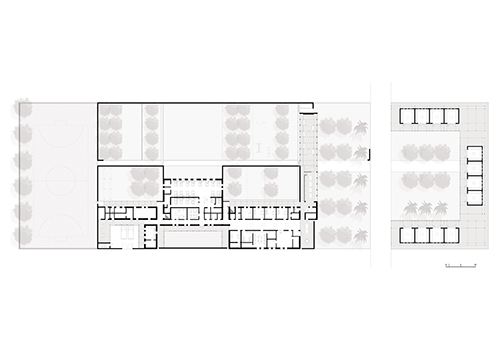

Location: Saint-Ours-les-Roches, Auvergne, France

Build: 1997 - 2002![]()

Illustration: Madalena Boavida Guerra, based on a cross section by Hans Hollein.

-

In 1994, Hans Hollein was commissioned to design a new European Park of Vulcanology, sited 1,000 metres up in the Massif Central. From afar the building, which is sunk three quarters underground, is reminiscent of one of his early collages: an aircraft carrier submerged in a landscape. Here though the main element is shaped like a volcanic cone, its exterior clad in black lava rock is wrapped around a shimmering gold interior. A ramp leads dramatically down to a subterranean floor where a series of galleries, a volcanic garden and an IMAX cinema are complemented by research and conference rooms. The route around the building was designed to take visitors on an emotional journey, inspired both by Jules Verne's Journey to the Centre of the Earth and Dante's Inferno, and intended to show “the primeval forces of nature and the creation of our planet”. But here the journey ends at the restaurant, where, due to the lay of the land, panoramic views open out to the vistas beyond: resurrection after the descent.

![]() (ltv)

(ltv)Exterior photo © Hans Hollein archive.

-

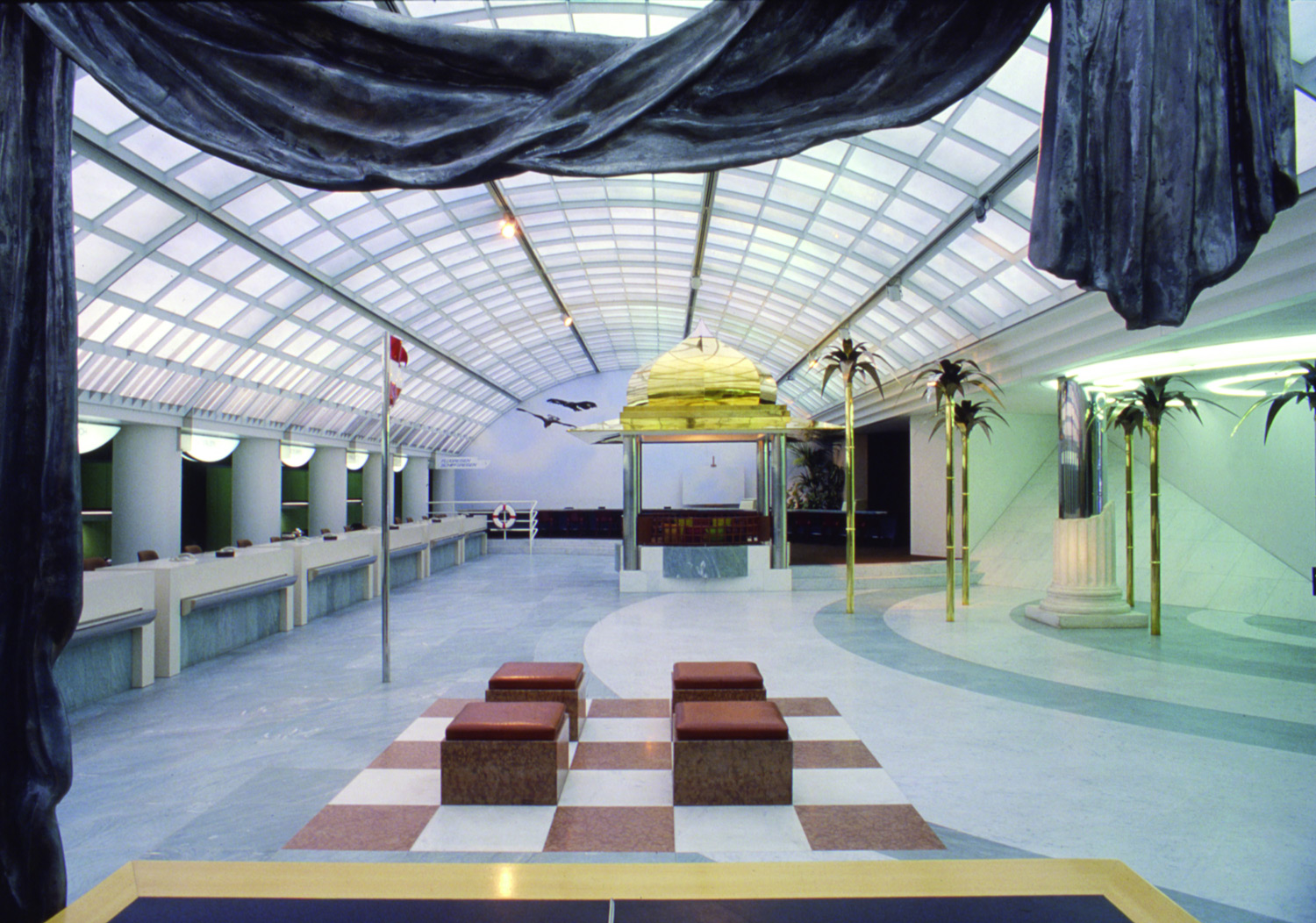

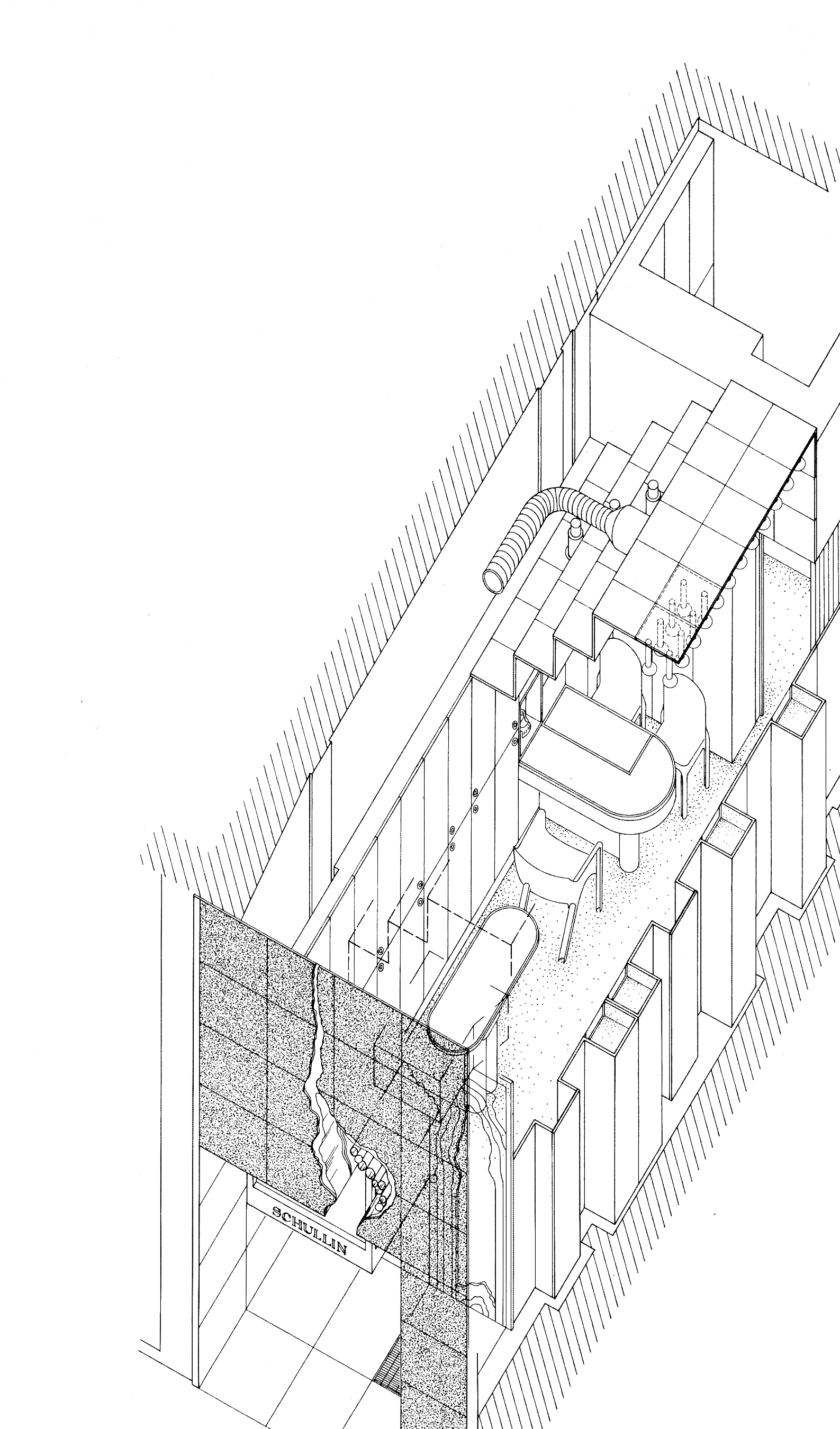

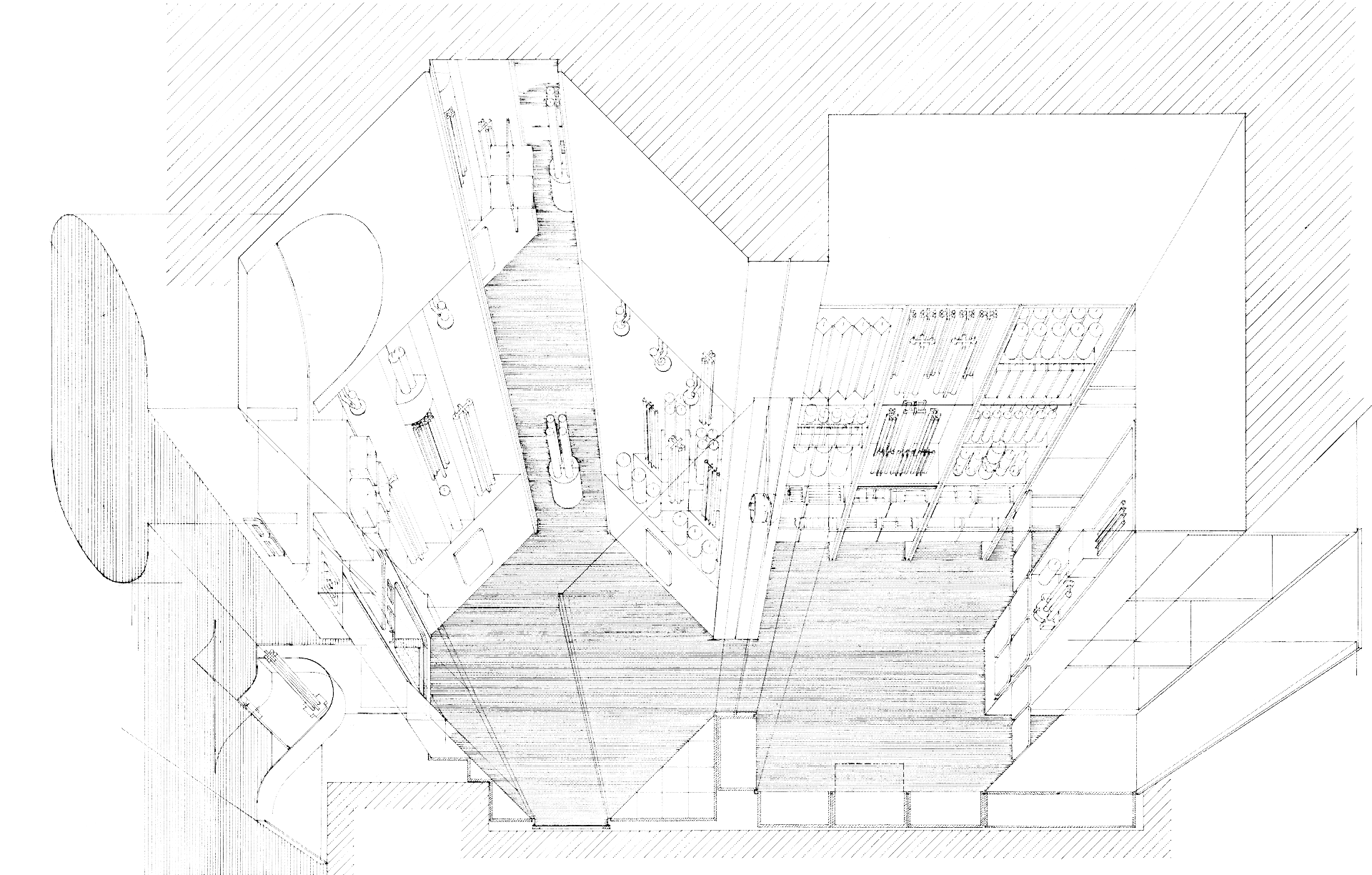

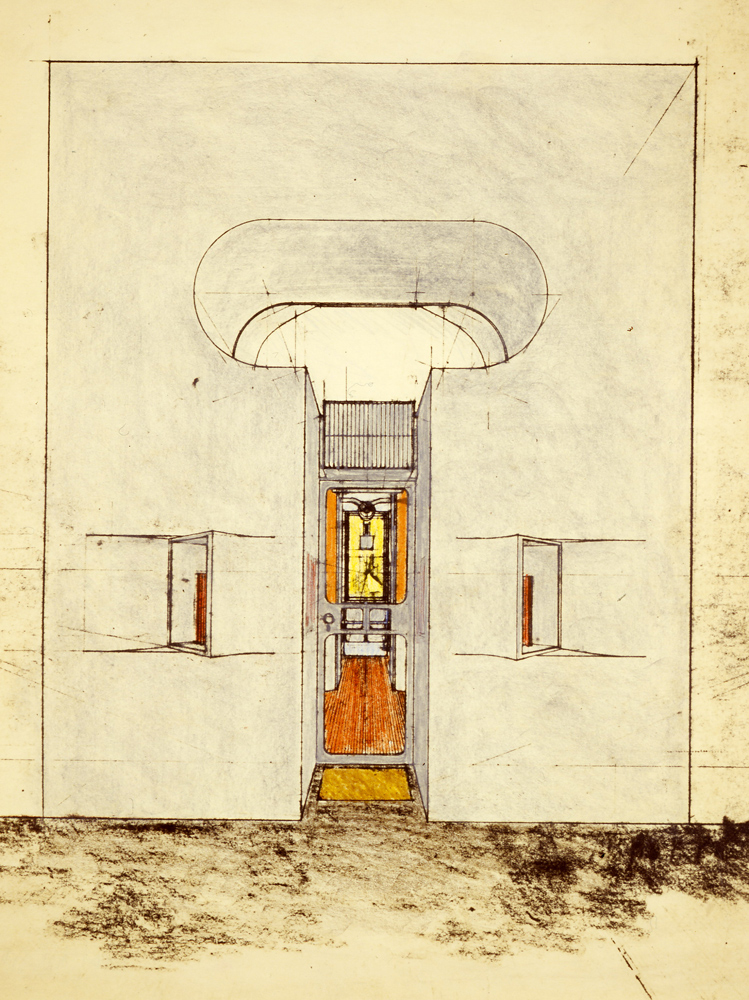

![]()

Hans Hollein’s Commercial Spaces

Hans Hollein’s belief in architecture as a form of communication is seen most purely – and extravagantly – in the retail spaces he designed. Here, practical function was reinforced by an underlying symbolism and fantasy, turning architecture into both medium and message. His first, the Retti candle shop (1964-65) on Vienna’s main shopping street, had a tiny 14.8 square metre footprint, which Hollein counteracted by adding a bold sci-fi looking aluminium façade, riffing off architectural history with its echoes of Ledoux in the inverted phallus-shape of its cut-out doorway, whilst leading to a rich almost chapel-like interior. Later, in 1978, he fitted out the Austrian Travel Agency in Vienna, where brass palm trees, Austrian flags and stage curtains cast in bronze, and a ruined Roman column in chrome created an environment where customers became actors in an elaborate theatrical performance about the exoticism of travel. (ltv & rgw)

-

![]()

![]()

Austrian travel agency‚ Vienna‚ 1979. (Photo © Jerzy Survillo‚ courtesy Hans Hollein archive)

-

![]()

![]()

Austrian travel agency, 1976-1978. (Photo © Jerzy Survillo, courtesy Hans Hollein archive)

![]()

Jewellery store Schullin 1, Vienna, 1972-1974. (Photo © Franz Hubmann, courtesy Hans Hollein archive)

-

![]()

![]()

Retti candle shop, 1965-1966, Vienna. (Photo © Franz Hubmann, courtesy Hans Hollein archive)

![]()

Sketch, Retti candle shop. (Image © Hans Hollein archive)

![]()

Retti candle shop‚ façade. (Photo courtesy MAK archive)

-

![]()

Walter Pichler, Hans Hollein’s radical collaboratorHans Hollein (left) and Walter Pichler (right), 1967. (Photo: F John Seiler)

-

In 1960s Vienna, the architecture community was in an uproar over the explosion of radical experimentation by the Viennese avant-garde, which included Hans Hollein alongside Raimund Abraham, Walter Pichler, Coop Himmelb(l)au, and Haus-Rucker-Co. In 1963, Pichler and Hollein created their seminal collaborative exhibition, Architecture at Galerie St. Stephan, an exhibition that was only on view for four days, but so controversial that university professors forbade their students to see it. Their 1962 manifesto, Absolute Architecture largely influenced Hollein’s views that would later be expressed in his 1968 manifesto, Everything is Architecture.

Walter Pichler, “TV Helmet (Portable Living Room)”, 1967. (Courtesy Generali Foundation © Archive Walter Pichler)

-

Walter Pichler (1936 - †2012) was an Austrian sculptor, architect, experimental artist, book and object designer. In 1963, he held his first exhibition with collaborator Hans Hollein at the Gallery St. Stephan in Vienna, which won both critical acclaim and controversy. His visionary architectural plans and artistic works dealt with themes of utopian ideals, experiments with space, and use of the physical body. Later he had seminal exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, Documenta 4 in Kassel, and Documenta 6. In 1972, Pichler retreated to an old farm house where he would create the rest of his life’s work.

The two collaborated throughout the 1960s, with shared views about expanding architecture outside of its boundaries. The two continued to influence each other’s work, creating collages, inflatable structures, wearable architecture, and minimal environments. After the 1960s, the two parted ways and Pichler began a life of seclusion. He retreated to his farmhouse, transforming it into a live-in interdisciplinary art piece where he spent the rest of his years.

![]() (Susie S Lee)

(Susie S Lee)Walter Pichler’s “Underground Building” project, isometric, 1963. Image © 2014 Walter Pichler, courtesy MOMA/Scala, Florence

-

Understanding the social, technical and environmental implications of building is essential in today’s networked world. And developing solutions to the problems we have both caused and inherited is the responsibility of all. The Zumtobel Group Award – Innovations for Sustainability and Humanity in the Built Environmentencourages and promotes exactly that sense of responsibility and to reward innovative endeavour. In the run up to the announcement of the winners in September 2014, and in collaboration with Zumtobel AG, uncube is presenting, in series, the best of the shortlisted candidates in each of the award’s three categories: Initiatives and Applied Innovations, Buildings and Urban Developments.

Part 2

Roden Crater image © James Turrell. (Photo: Florian Holzherr)

-

La Chesnaie in Saint-Nazaire is a run-down 1970s high-rise housing estate by the sea that has lost much of its attractiveness in recent years. The architects Lacaton & Vassal proposed a long-term requalification through the radical transformation of 40 apartments in one of the existing high-rises and increasing densification by grafting 40 new dwellings onto its gable ends.

Each apartment profited from an increase in surface area of 33 sqm without any major structural works affecting the organisation of the building. Each apartment gained a balcony, an extra bedroom, a new bathroom with a window and a two-metre-wide climate control device consisting of moveable transparent panels with fabric screens which doubles as a winter garden.

This treatment of the block proved much more cost effective than demolishing the 40 existing flats and building 80 new ones. If developed in other buildings in the area, the principle of densification would permit the construction of 258 new dwellings, the qualitative transformation of 312 flats, and the creation of new local amenities and services, without eating into the large central park.

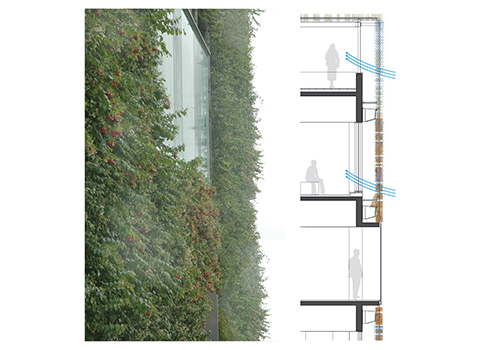

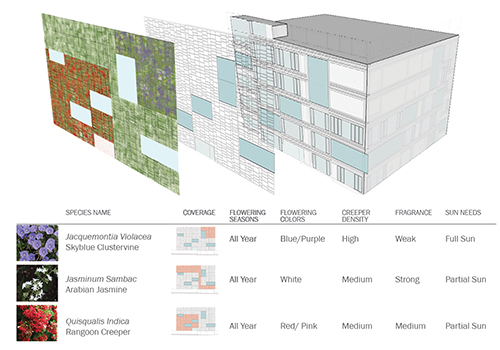

This corporate building employs the idea of a double skin, as an energy saving and visually dynamic mechanism. The inner facade of the building is a reinforced concrete frame with operable windows. The outer facade is comprised of a custom cast aluminium trellis with hydroponic trays and a drip irrigation system for growing a variety of plant species. The trellis also has an integrated misting system hydrating the foliage in order to control and regulate the release of water and mist to cool the building.

The trellis also takes on an aesthetic function: assorted species are organised to bloom at various times of the year, bringing attention to different parts of the building facade throughout the changing seasons. Twenty gardeners tend to the façade garden, accessing it though a system of catwalks on all five levels. The proximity of gardeners to the interior office spaces drives a daily visual conversation between building’s occupants and carers. This should also help soften the social threshold created by class differences that are inevitable in corporate organizations in India.The decision, to handcraft the façade trellis in a village in South India, was intended to demonstrate the skill and craft that could be brought to bear on materials that are otherwise associated with mass production.

Over the last 30 years, migration in China has had a dramatic effect on both urban and rural areas. Imported labour and materials are replacing collective self-construction and there is a shift from economic self-reliance to a system of dependency. This dwelling project is focused on self-sufficiency.

The design features a multifunctional roof, providing a space for drying food, steps for seating, and a means to collect and store rainwater. The courtyards house pigs and an underground biogas system produces energy for cooking. Smoke from the stove is channelled through a traditional heated bed before exiting through the chimney.

Four functional courtyards are inserted throughout the unit to relate to the main functional spaces: kitchen, bathroom, living room, bedrooms. Each is spatially unique. Mud bricks are used to further integrate them into the surrounding building styles. A new concrete column and roof structure is combined with mud brick infill walls - a traditional medium of insulation. The outside wall is wrapped in a brick screen, protecting the mud walls and shading windows and openings.

The House is currently managed by Qiaonan Town Womens Federation and the Shijia Village committee and has become a woman’s training centre for traditional weaving. It is hoped that this will aid the village in its economic self-sufficiency and improve the political status of women.Category 2 – Buildings

The Buildings category was open to built projects completed between 2011 and 2013 which met the highest aesthetic standards and featured innovative solutions that led to the more efficient use of resources, enhanced environmental protection and the creation of better living conditions. The jury paid particular attention to the use of state-of-the-art technology and shortlisted five finalists from 146 submissions:

Transformation, Extension and Densification

Saint-Nazaire, La Chesnaie, France

Lacaton & Vassal architectes, Paris

A clever, cost-effective upgrade of a 1970s apartment block to improve living quality and energy-efficiency by grafting on winter gardens, balconies and 40 new apartments.![]()

Green Double Skin

Hyderabad, India

RMA Architects, Mumbai

An office building with a handcrafted, cooling, double-skin garden façade. It allows visual connection between office staff and façade gardeners, bridging social strata and creating “green jobs”.![]()

Rethinking the Rural

Shija, Shaanxi province, China

Rural Urban Framework, Hong Kong

A prototype for a new rural vernacular preserving local knowledge, and materials, encouraging self-sufficiency and supporting the local economy.![]()

-

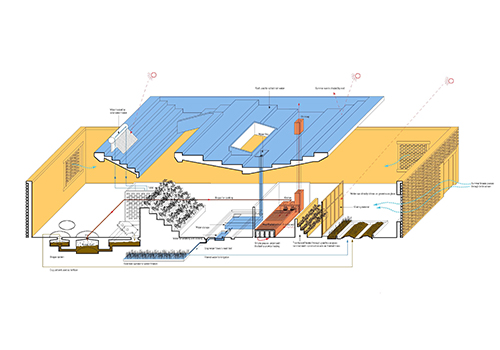

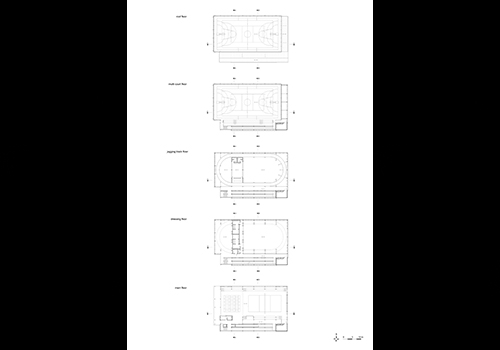

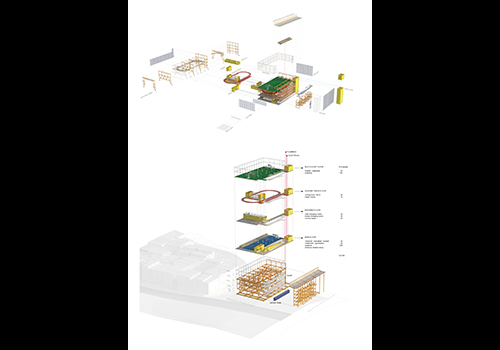

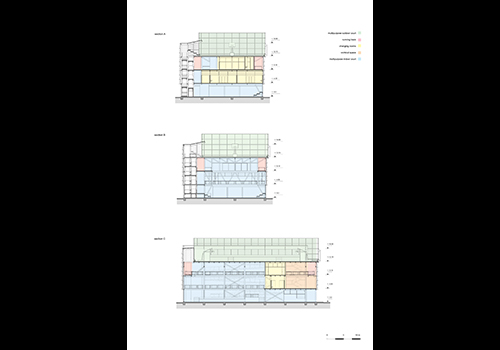

The Vertical Gym is a low-cost, flexible design for a multi-level recreation complex, comprised of a pre- fabricated kit of parts that can be assembled in 3 months. It can be customised to maximise the latent potential of any public space, particularly within informal settlements characterized by dense urban fabric, resource constraints and irregular topography. The base is superimposed upon an existing sports field or vacant lot, transforming it into a safe facility for exercise and piece of social infrastructure that has reduced crime rates, promoted healthy lifestyles and strengthened social capital.

Designated recreation spaces are limited in Venezuela, where over half the population lives in dense urban areas, where the lack of available land is only one of many challenges, alongside high crime rates, gang activity and a scarcity of resources to assist in promoting healthy lifestyle choices.

Now realised in four sites around the city, the structure can be custom configured over three levels to support a multitude of sports and cultural activities, capped by a rooftop open-air soccer pitch with covered spectator zone. Bypassing the need for costly elevators, users access the different levels via a circular ramp system, which simultaneously functions as a 100m running track. The building design also allows for the incorporation of advanced sustainability features, including solar cells, wind turbines and rainwater collection for irrigation and grey water applications.

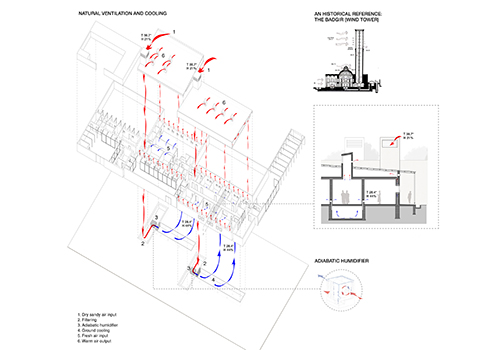

The Port Sudan Paediatric Centre is located in a large desert between two hut settlements. It is a very poor area with a large concentration of refugees. This clinic is one of the few health outposts providing free health care to children of this large region. The building was designed for Emergency, an Italian NGO who provides free medical and surgical treatment to the civilian victims of war, landmines and poverty.

Because of the extreme conditions involved, simplicity was a strategy priority for this project, but without losing sight of quality medical and architectural standards for the project.

The one-storey building has three outpatient clinics, a 14-bed ward, a dispensary, spaces for diagnostic exams and service areas. The building adopted the adaptive principles of many Arab houses: minimising sun-exposed sides and opting for a hollow space conformation. As the Sudanese climate is extreme (50 degrees Celcius and sandstorms) a natural air treatment inspired by Iranian traditional systems called a badgir was adopted and integrated into a system of mechanical cooling. The resulting reduction in electricity consumption for air conditioning is estimated at about 70 per cent.

The need to purify wastewater from the clinics presented an opportunity to build public gardens - the only public spaces in the area: treatment for the water, and for the souls of patients and staff alike.Category 2 – Buildings

The Buildings category was open to built projects completed between 2011 and 2013 which met the highest aesthetic standards and featured innovative solutions that led to the more efficient use of resources, enhanced environmental protection and the creation of better living conditions. The jury paid particular attention to the use of state-of-the-art technology and shortlisted five finalists from 146 submissions:

About the Jury

The expert jury panel for the Zumtobel Group Award 2014 includes:

Kunlé Adeyemi – Architect & Urbanist / Founder NLÉ, Amsterdam (NL)

Yung Ho Chang – Architect / Studio FCJZ, Beijing (CN)

Brian Cody – Chair of the Institute of Buildings and Energy, Graz University of Technology (AT)

Winy Maas – Architect / MVRDV, Rotterdam (NL)

Ulrich Schumacher – CEO Zumtobel Group

Kazuyo Sejima – Architect / SANAA, Tokyo (JP)

Rainer Walz – Head of the Competence Center Sustainability and Infrastructure Systems at the Fraunhofer Institute for Systems and Innovation Research ISI in Karlsruhe

House of Healing

Port Sudan, Sudan

Studio Tamassociati Architects, Venice

A NGO clinic that provides treatment for the civilian victims of war, land-mines and poverty. The design combines new and old technologies and has a garden to help emotional healing and restore social interaction.![]()

Vertical Gym

Barrio Santa Cruz Del Este, Caracas, Venezuela

Urban-Think Tank, Zurich

This multi-level gymnasium acts as an urban catalyst, revitalising and upgrading underdeveloped areas and partnering with the local council, industry and organisations as well as promoting healthy lifestyle choices.![]()

previously featured categories:

upcoming categories:

URBAN DEVELOPMENTS

&

INITIATIVESTHE WINNERS

will be announced in London on the 22nd September 2014

and presented in the October issue of uncube

The Jury -

![]()

by Wilfried Kuehn and Marlies WirthPhoto courtesy MAK

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Wilfried Kuehn (of Kuehn Malvezzi Architects) and Marlies Wirth (curator MAK), joint curators of the Hollein retrospective currently showing at the MAK museum in Vienna, explain what made this extraordinary all-rounder so significant and why Hans Hollein really was all about “architecture and beyond”.

Hans Hollein (1934–2014) was a Pritzker Prize-winning architect, designer, artist, curator, exhibition organiser, theorist, educator, city planner, media visionary, and cultural anthropologist. As a designer in the most comprehensive sense, Hollein gave the term “architecture” a new dimension and his still relevant analysis of “a world shaped by man”, turned a fundamental question into a visionary statement: “What is design?” Here, we try to pinpoint his main areas of influence and innovation through key areas of his practice and specific projects from his long and rich career. The accompanying photographs are a selection from new images of Hans Hollein’s buildings especially commissioned for the Hollein exhibition from the artist-photographers Aglaia Konrad and Armin Linke.

-

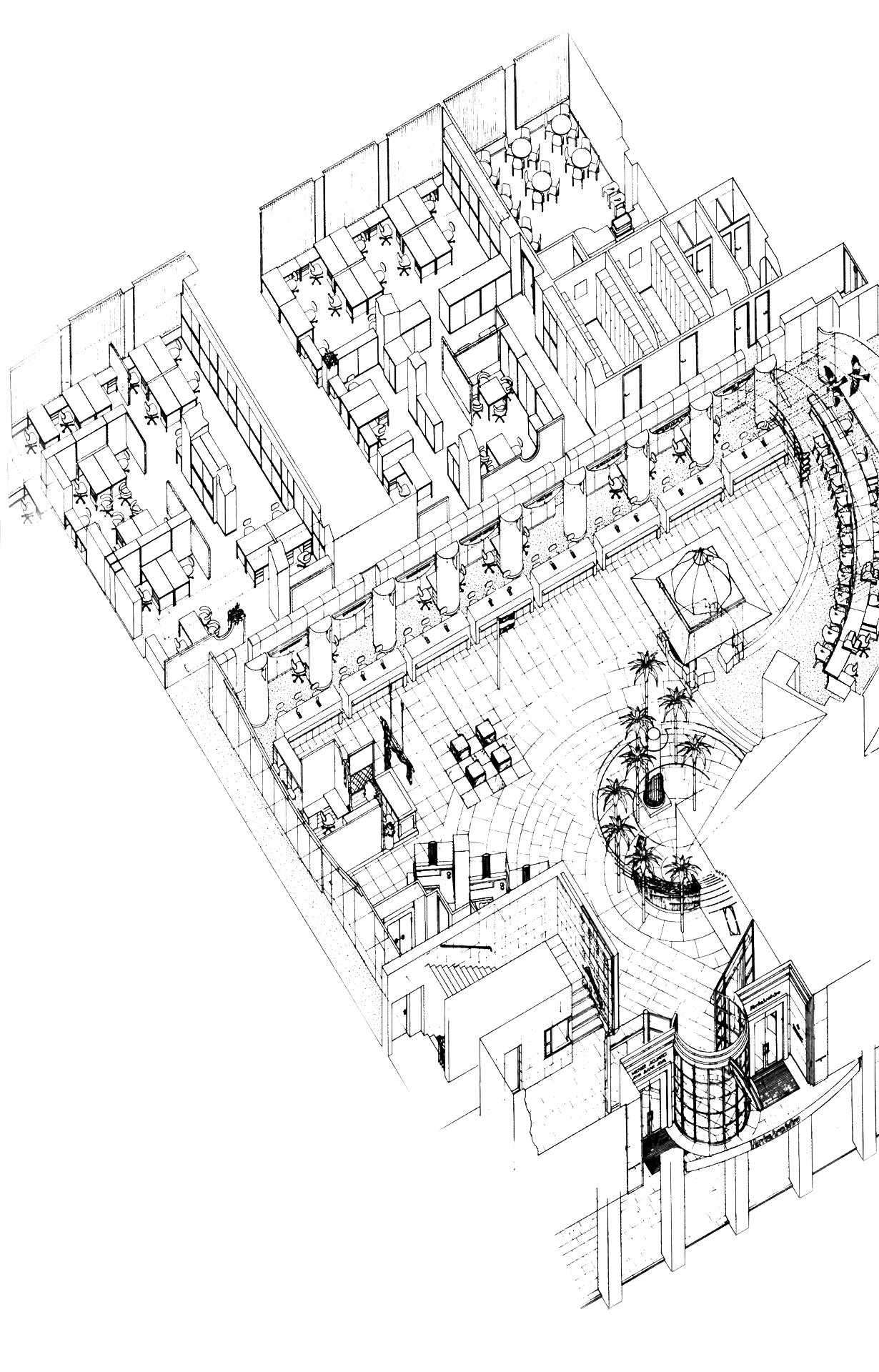

The Building Unfurls Itself

Hollein’s interest in museums was an interest in the exhibiting process. His aim was to design displays of museum collections as experimental, shifting arrangements in space rather than canonical art historical presentations. The Museum Abteiberg (1978-82) plays a pivotal role in Hollein’s oeuvre. In its heterogeneity the building is a sequence of spaces, each with its own unique character. They do not form some ideal whole but function more like a montage of contrasts. The museum architecture is neither a typologically idealised space nor a generic real space; it is a hybrid. Hollein created the conditions for artistic production and spatial installation but also for exhibition formats that expand performatively. Due to intersections designed around his “clover leaf” pattern floorplan, the building unfurls itself in the heterogenous paths of the visitors as a series of situations, alternating with, and following on urprisingly from, one another: suddenly coming into view and disappearing again like variations in a landscape.

The room progression concept that was developed for the Museum Abteiburg transforms the open corners of the rooms into pivotal points that activate the visitors in the exhibition space. Their gazes and movements interconnect the rooms and the works installed within them, replacing the traditional linearity and chronology of the exhibition situation with one of simultaneity. Hollein’s typological innovation was an expression of the shift that had taken place in the museum in the wake of the buildings of late Modernism, such as Ludwig Mies van der Rohe‘s Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin in 1967. Like Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers’ Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, also designed in the 1970s, the Museum Abteiberg was a radical new exhibition space integrated into the everyday fabric of the city rather than sitting elevated above it like a temple. Hollein designed the museum from the inside out, as a space for producing and experiencing the exhibiting process. It was conceived as an urban space in the urban context that continues and expands around it like an artificial landscape.Museum Abteiberg Mönchengladbach, 1972-1982. (Photo: Aglaia Konrad)

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

Museum Abteiberg Mönchengladbach, 1972-1982. (All photos: Aglaia Konrad)

-

The Kinaesthetic Experience of Space

The exhibiting process and the visitors’ kinaesthetic experience of space stand at the heart of Hollein’s work. The Museum Abteiberg is an “accessible house”, the first Hollein built after working on the idea as a student. Back in 1958, when visiting the US for the first time, Hollein showed particular interest in the Native American pueblos in the New Mexico region, basic adobe dwellings and settlements as distinctive as they are complex. The term pueblo stands for the individual and the whole: the house is the city, the architecture is the accessible landscape; the private is related to the public, the ritualistic to the quotidian. In his designs for the central Sparkasse bank in Vienna’s Floridsdorf district and for an accessible department store in St. Louis, Hollein transformed the step-like constructions of traditional adobe buildings into models for accessible houses, which generated public space on their terraced roofs. It was with the Museum Abteiberg that Hollein was first able to realise his idea of a building as landscape and public space rolled into one; it gouges itself into the hillside and offers its own roof as urban space.

In the Volksschule Köhlergasse, realised in Vienna in 1990, Hollein applied his accessibility principles to a school building. Every classroom was given its specific shape using special ceiling formations and he added a series of semi-public spaces to function like city squares. These spaces, where interior and exterior meet, generate a city within a city that is inhabited by children. During breaks between lessons, they can enter this outside space that is also public space, and learn to occupy it. By upgrading these interstitial spaces Hollein brings the urban environment into the school and with it, the opportunity for the children to subjectively appropriate their school environment as a constellation of situations and spaces.Elementary School VS Köhlergasse, Vienna, 1979-1990. (Photo: Aglaia Konrad)

-

Aglaia Konrad was born in 1960, Salzbourg, and lives and works in Brussels. She is an artist who has developed a distinct manner of photography that documents the rapidly advancing process of global urbanisation. Her archive, which encompasses several thousand images of urban infrastructures and housing architectures, offers an unlimited repository that sheds a unique light on the relationship between society and space.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Elementary School VS Köhlergasse, Vienna, 1979-1990. (All photos: Aglaia Konrad)

-

Everything is Architecture

Hollein addressed the influence of the environment in the broadest sense of the word in his masters thesis at Berkley in 1960, in his 1963 exhibition Architecture with Walter Pichler in the Galerie St. Stephan in Vienna, and again in his 1976 manifesto Everything is Architecture in Bau, the magazine he published. During this period he created a series of projects that tested the physical limits of spatial awareness and how potentially to overcome them: Communication Interchange (1963), as a city model of total interconnectedness;

Minimal Environment (1965) in the form of a telephone cell as total habitat; Non-Physical Environment (1967) in the form of a pill; Spray zur Umweltveränderung [Spray for Changing the Environment] (1968) and his Vorschlag für die Erweiterung der Universität Wien [Proposal for Extending the University of Vienna] (1966) in the form of an informational rather than physical network that was a more radical alternative to Cedric Price’s Potteries Thinkbelt university concept from the same year.

The Indissoluble Relationship

The concept of “mediality” – a media-saturated reality – is central to Hollein’s work and underpins each of his projects. His starting point is the indissoluble relationship of permanent mutual production into which man and environment are locked. In this process, as Hollein posited in his curatorial-architectural plans for his MANtransFORMS 1976 exhibition at the Cooper Hewitt Museum, New York, design constitutes the prototypical human activity of environmental production. At the centre stands the Body, in the force field of Space and Time Experienced, of Behaviour, Politics, Face and Tools.

Media Lines Olympic Village, Munich. (Photo © Armin Linke, 2013)

-

In between are conjoining themes like living together, eating, clothing, tools, ritual, death, drugs, etc. Instead of valuable artefacts he presented everyday objects and their production through human activity. Using the topos of “A Piece of Cloth” Hollein showed variations of a simple object right the way through to the development of complex human achievements such as housing, protection and ritual, flags, communication media, tools, energy generation and mobility. In front of the entrance to the Cooper Hewitt National Museum, Hollein installed a tree trunk whose base was still covered in bark and whose top had been planed to a timber beam. Half-nature, half-artefact, it stood for Hollein’s entire exhibition project in which design was presented as the transformation process of man and object as well as the potential for social processes.

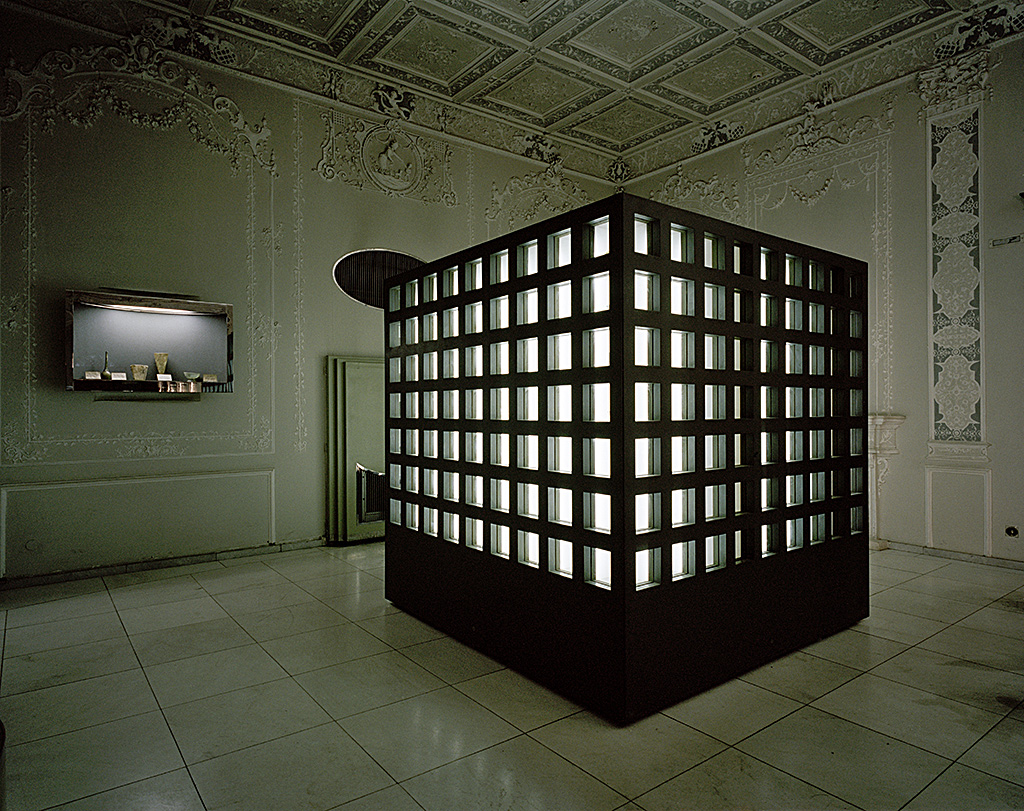

The Media Lines, realised in Munich in 1972, were the prototype for Hollein’s media environment-as-architecture. They formed an environmental conditioning and communication system for the Olympic Village, which could also be read as public art, architecture and guidance system. In his projects of the 1970s Hollein transformed the pipes of the Media Lines into a museum display system, most notably in the 1978 Tehran Museum of Glass and Ceramics.

The museum in Tehran reads like a catalogue of display solutions that appear as strange vitrines implanted into the historical building. Like minimal environments mounted into the fabric of the museum, the vitrines are the communicative end point of their own network and occupy selected spaces around the building, from the exterior wall to the parquet floor, functioning as a museum in a museum.Media Lines Olympic Village, Munich. (Photo © Armin Linke, 2013)

-

Armin Linke was born in 1966 and lives in Milan and Berlin. He is an artist working with film and photography, combining different mediums to blur the border between fiction and reality. He is working on an ongoing archive concerning human activity, and natural and manmade landscapes. He is professor at the HfG Karlsruhe, guest professor at the IUAV Arts and Design University in Venice, and Research Affiliate at the MIT Visual Arts Program, Cambridge.

![]()

Media Lines Olympic Village, Munich. (Photo: Armin Linke)

![]()

Museum of Glass and Ceramics, Tehran. (Photo: Armin Linke)

-

Marlies Wirth is a curator and art historian based in Vienna. Since 2006 she has worked at MAK – Austrian Museum of Applied Arts / Contemporary Art where she curates exhibitions as well as temporary interventions and performances in the fields of art, architecture, design and fashion. With a focus on conceptual, site-specific, research- and time-based art and architecture she is also interested in the interconnection of contemporary art production and museum collections as well as new forms of exhibition display outside the classic museum presentation.

Wilfried Kuehn is an architect and curator based in Berlin and Vienna. He taught exhibition design and curatorial practice at the Karlsruhe University of Arts and Design from 2006 to 2012. With Simona Malvezzi and Johannes Kuehn he founded the Berlin based partnership Kuehn Malvezzi in 2001. Public space and the Arts are the main focus of their work as architects, designers and curators. Works include the extensions of the Museum of Contemporary Art Hamburger Bahnhof and of the Museum Berggruen in Berlin and the Julia Stoschek Collection in Düsseldorf. Kuehn Malvezzi has featured in a number of exhibitions, amongst others in the 10th, the 13th and the 14th Architecture Biennial in Venice and at Manifesta 7 in Trento. Together with artist Armin Linke Wilfried Kuehn curated and designed the exhibition 'Carlo Mollino - Maniera Moderna' at Haus der Kunst, Munich in 2011.

The exhibition Hollein (25 June – 5 October 2014) at the MAK in Vienna (link) was prepared in collaboration with the Museum Abteiberg, Mönchengladbach (link), currently showing the exhibition Hans Hollein: Alles ist Architektur [Hans Hollein: everything is Architecture] (13 April – 28 September 2014).

Forthcoming book:

Hans Hollein

photographed by Aglaia Konrad and Armin Linke

Ed. Wilfried Kuehn, Christoph Thun-Hohenstein, Susanne Titz, Marlies Wirth

MAK – Austrian Museum of Applied Arts / Contemporary Art, Vienna

Museum Abteiberg, Mönchengladbach

Mousse Publishing, Milan

2014

German/English, ca. 120 pages

moussepublishing.com

Hollein’s Protagonist

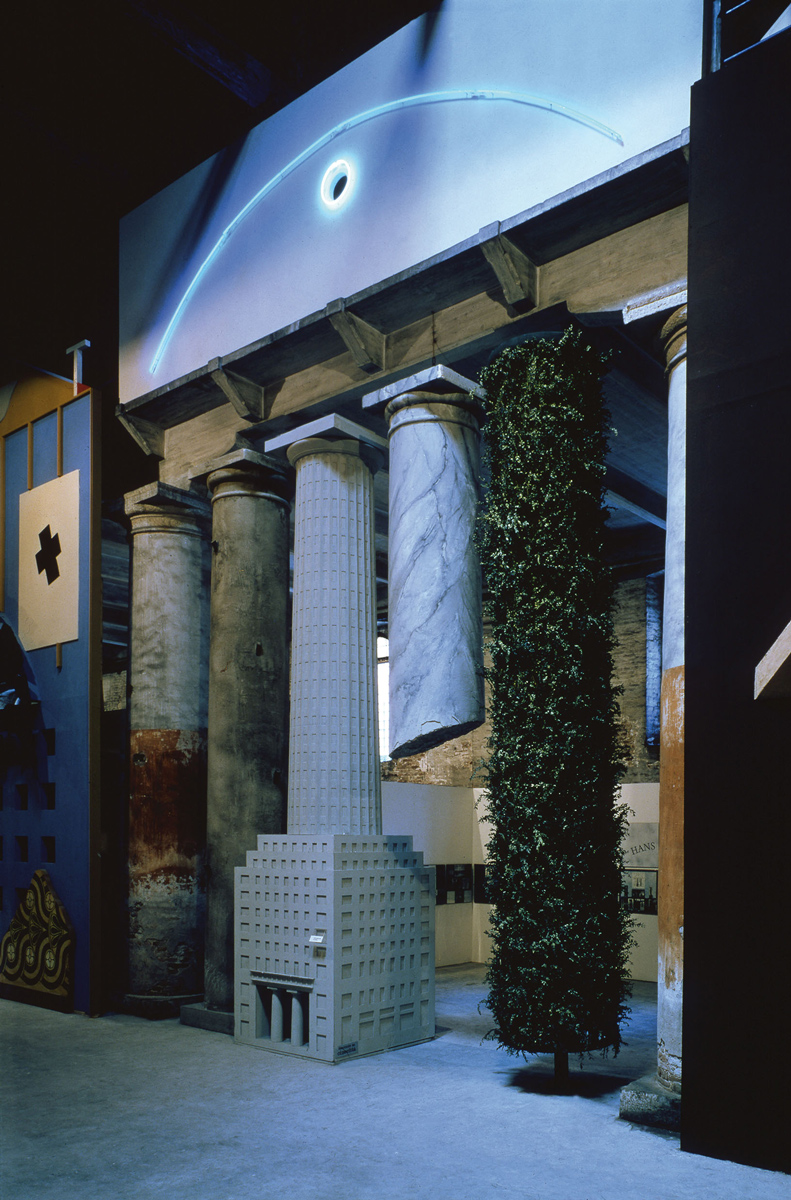

The column is the model based on Hollein’s skyscraper drawings from 1959; it runs through the Olympic Village as a Media Line and surfaces again as vitrine in Tehran and palm tree in the Austrian Transport Office in Vienna. At the first Architectural Biennale in Venice in 1980 the column was Hollein‘s protagonist. His contribution to the Strada Novissima exhibition curated by Paolo Portoghesi was an essay about the potential of columns to generate new spaces.

From the starting point of the contextual columns of the Corderie in the Venice Arsenale (the site of the 1980 Biennale), Hollein installed four of his own altered columns, each of which had morphed into a different object:a bare tree, a tree covered in dense foliage, a suspended stone column whose bottom half had been lopped off, and a huge model of Adolf Loos’ design for the Chicago Tribune Tower. Hollein inverts Loos’ readymade by reverting the classical column that Loos had transformed into a skyscraper back into a column again. Through changes in scale or material, through shifts from one context to another, Hollein activates the potential of objects, using them to generate new environments and create meaning and spaces that transcend the preexisting architectural programme.

![]() (Translated by Lucy Powell)

(Translated by Lucy Powell)Strada Novissima, “The Presence of the Past” exhibition, Venice Biennale, 1980. (Image © Hans Hollein archive)

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

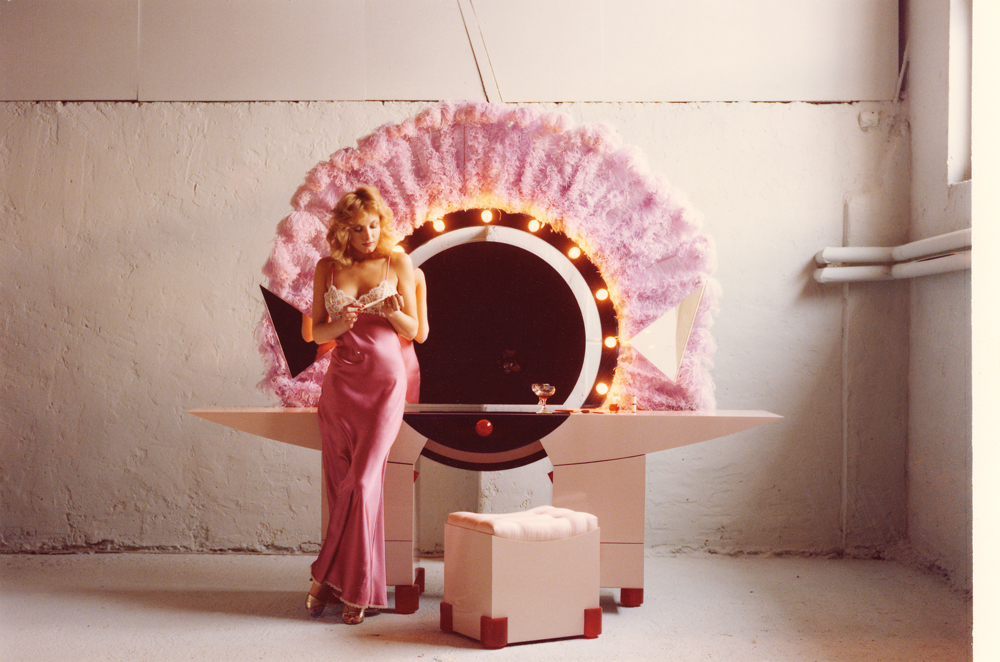

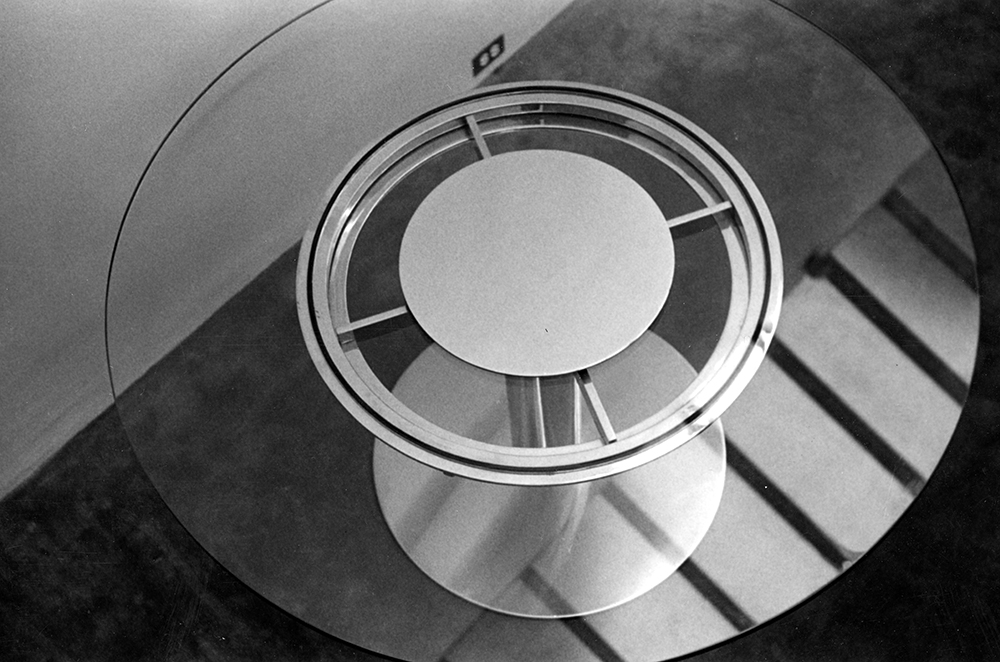

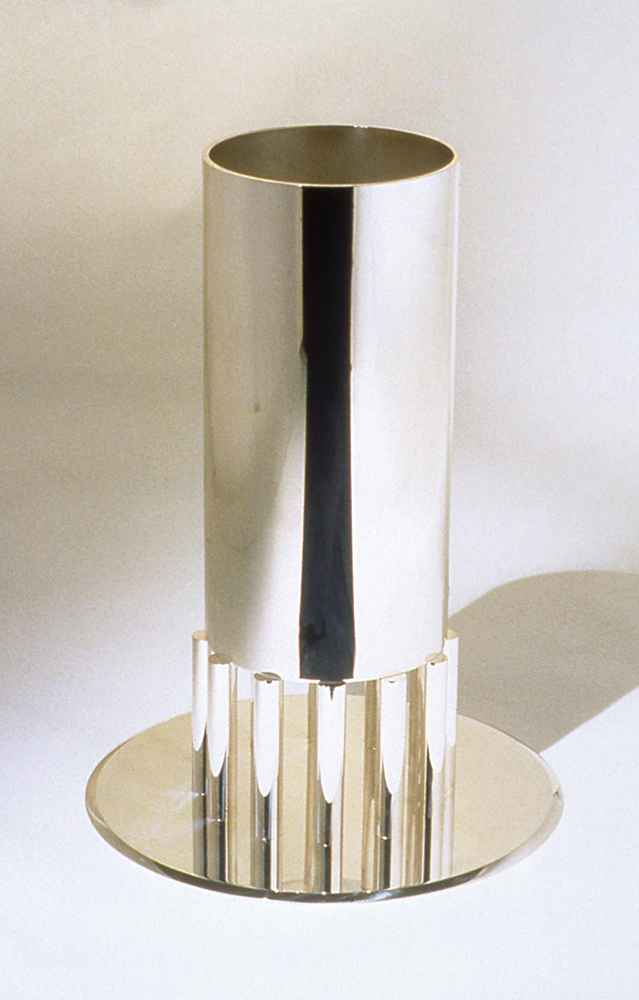

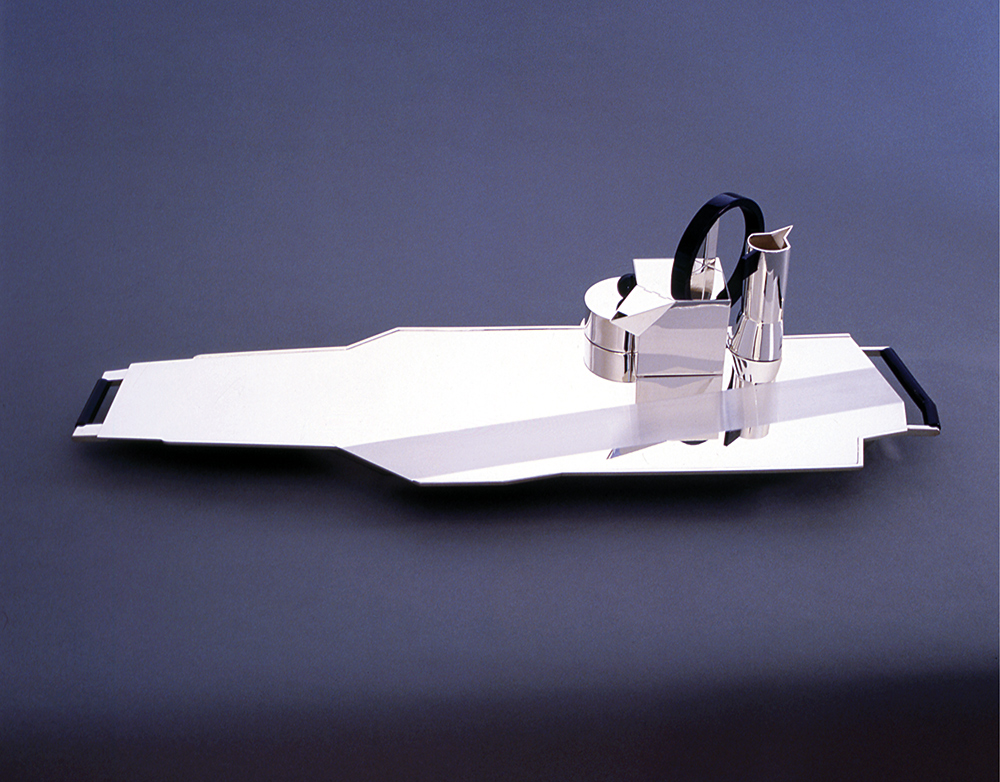

Hollein’s Design Objects

Hans Hollein’s credo: “Everything is design” fitted the architect’s extremely multidisciplinary interests. When he wasn’t busy writing manifestos, curating exhibitions, designing interiors, drawing, painting, teaching or (even) designing buildings, he turned his attention and flair for shapes to a whole range of products. In the 1960s, for example, he designed a desk for Hermann Miller; in the 1970s a furniture collection for Wittmann and a rather whimsical sunglasses collection for AO in the USA. A flirtation with Memphis in the 1980s led to a sofa, and vases in silver and Murano glass for another Italian avant-garde company, Cleto Munari. He joined the Alessi hall of architectural fame with a tea and coffee set for them in 1980, and in 1990 designed an extraordinary (but perhaps ill-advised) concert grand piano for Bösendorfer that Liberace would have died for had he not been dead already. (sl)

All photos courtesy Hans Hollein archive.

-

![]()

Vanity dressing table for M.I.D‚ 1982, Austria.

![]()

Roto Desk for Hermann Miller, 1966. (Photo © Franz Hubmann)

-

![]()

Simplexity collection at the Design Gallery Milan, 1994. (Photo © Aldo Ballo)

![]()

Centrotavola collection designed for Cleto Munari, Vincenza, 1980. (Photo © Aldo Ballo)

![]()

Simplexity collection at the Design Gallery Milan, 1994. (Photo © Aldo Ballo)

-

![]()

Diagonal Furniture Ensemble for Wittmann, Vienna, 1975.

![]()

"Palme" brooch for Köchert, Vienna, 1987.

![]()

Tea and coffee set for Alessi, Crusinallo, 1980. (Photo © Aldo Ballo)

-

![]()

Grand Piano for Bösendorfer Klavierfabrik AG, Vienna, 1990.

![]()

Murano glass vase for Cleto Munari, Vicenza, 1989. (Photo © Aldo Ballo)

-

![]()

Hans Hollein’s Museum for Modern Art

in Frankfurt am MainText by Oliver Elser

MMK Museum für Moderne Kunst Frankfurt am Main. (Photo © R Örlimans, courtesy Hans Hollein archive)

-

![]()

Oliver Elser, Po-Mo fan, architecture critic and a curator at the Deutsches Architekturmuseum (German Architecture Museum), gives an insider view on one of Hans Hollein’s best-known museums, the MMK in Frankfurt, its pitfalls and plus points and the ongoing politics relating to its construction.

As of October “there will be three of us” announce the billboards for the Museum for Modern Art (MMK) in Frankfurt. Three of us? Is the museum expecting offspring? It is indeed. In the German financial capital where growth, yield and quantifiable success are familiar terms even in the cultural sphere, the MMK is expanding its exhibition space across three locations.

The MMK 1, the Hollein building, is the original, which was inaugurated in 1991 and was far too small from the outset. Even at the opening, the first director, Jean-Christophe Ammann, wished for nothing more than another building. Which is one reason why he was always at loggerheads with his architect, Hans Hollein. But we'll get back to that in a moment. Today, just over two decades later, the current director, Susanne Gaensheimer, is at last getting a new annexe, which will be known as MMK 2.

Looking west from Berliner Street. (Photo © R Örlimans, courtesy Hans Hollein archive)

-

And since it‘s in Frankfurt, a banking city, it will be housed at the base of a new skyscraper, the Taunus Tower. The architects of the 170-metre-tall office tower are Gruber + Kleine-Kraneburg of Frankfurt; the 2,000 square metre exhibition space has been designed by Kühn-Malvezzi, Berlin. This location, in the centre of the financial district and some way off the beaten cultural path, will house temporary exhibitions from the permanent collection, while highlights of the collection and important special exhibitions will be presented on the main site, the Hollein building. And then there is MMK 3, situated opposite MMK 1, in the former central customs office designed by Werner Hebebrand in 1927, and where, for the past few years, works by mostly younger artists have been on show.

![]()

![]()

The Hollein Museum was, as mentioned before, never big enough for Ammann, its first director – and he never liked it architecturally either. Hans Hollein won the competition in 1983 but that was under his predecessor, Peter Iden. Heinrich Klotz, director of the new Germany Architectural Museum and an outspoken defender of postmodernism had sat on the jury, and was dead set on pushing though Hollein’s design, having failed to get his way with Charles Moore or Venturi, Rauch + Scott-Brown elsewhere in Frankfurt. Hollein not only had powerful backers – at least at the start – but his was also the best design (the competition included the young Rem Koolhaas). Then Iden threw in the towel and Jean-Christophe Ammann came from Switzerland to take over.

Top photo © Alex Schneider, courtesy MMK. Bottom photo © R Örlimans, courtesy Hans Hollein archive.

-

![]()

Model photo © Alex Schneider, courtesy MMK

-

![]()

All he wanted was a big white box with neutral rooms. The opposite, in other words, of Hollein’s design, which was by then already so far into the planning process that only details could be changed.

Yet you only have to abstract a little and the MMK starts to look like a big white box, at least from the outside. The two long sides of its isosceles triangle shape (it is known locally as “The Piece of Cake”) are huge, bare, dirty white plaster façades, onto which Hollein daubed a few architectural elements (here a window, there a bay front, here a balcony, at the bottom an arcade) in a spacious composition. It was as if he had wanted to take Brian O’Doherty’s famous white cube formula, which automatically elevates everything exhibited within it to a work of art, and test it out on the building’s exterior. As if to say: “Look at what I’m showing on these bare white exterior walls, it’s certain to spark off a dialogue with the art inside!” But even the most well-meaning critics such as Joseph Rykwert, who at the opening wrote a cover story about the MMK for domus, reserved their compliments for the building’s interior qualities.

Everything inside the MMK is white, but there’s nothing remotely neutral about it. It’s all acute angles, interior balconies, surreally shaped stairways and footpaths across dizzying drops. Hollein talked about rooms with character. There’s a nice anecdote about the huge model that he constructed at 1:50 scale to convince the doubtful director that his collection would fit perfectly into the plethora of exquisite exhibition rooms. The model was designed to be taken apart so that you could look into each room at the eye level of the museum visitor. Several dozen photographs of scaled-down art works in the collection were arranged on the walls.![]()

-

Oliver Elser is a curator at the Deutsches Architekturmuseum (DAM) in Frankfurt. His current exhibition is Mission Postmodern – Heinrich Klotz and the Wunderkammer DAM.

See his blog interview about Heinrich Klotz and postmodernism here

![]()

Hollein’s team had also lovingly recreated the sculptures as miniature models within the model. Ammann literally exploded when he saw it. He was outraged that Hollein was now trying to play curator and sticking his nose into the hanging of the collection. How dare he! When the model was returned from Paris slightly damaged and in need of repair, Ammann gave instructions to have all the art stripped out of it. Yet the MMK is one of the few museums where room and artwork merge into powerful symbiosis. Katharina Fritsch’s Tischgesellschaft looked as if it had been made especially to be shown in one of the arrow-shaped rooms of the museum’s 30-degree prow. And anyone who saw Thomas Ruff’s ultra-cool portrait series in the ice-cold central hall with the balconies will have it burned into their retinas forever.

The rooms between the art, mountainous and gorge-like staircases, are similarly unforgettable experiences. Hollein always dreamed of creating archaic spaces for his architecture, spaces not created by building, which is generally understood as the addition of elements, but through its inverse: carving out, removal and embedding. For the MMK he created a landscape of craggy cliffs. Most people will agree that its suite of rooms are among the most magnificent in Hollein’s oeuvre.

Of course, they will say, it is his spatially most exciting work, in spite of its postmodern façade. But the façade, hmm. In 2009 the arts editors at the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung even suggested dazzling it away with a camouflage pattern by the artist Tobias Rehberger. But isn’t it time to finally take the disturbing exterior at face value? As an attempt to form from fragments a building, which in its bittiness has all the unruliness that we’ve learned to appreciate in good art? There‘s still a long way to go. The postmodern revival has only just begun.

![]() (Translated by Lucy Powell)

(Translated by Lucy Powell)Tobias Rehberger, “Dazzle”, design for the MMK. (Image © Tobias Rehberger, courtesy MMK)

-

![]()

Mobile Office

The 1960s and 1970s, inflatable architecture was very en vogue with the Viennese avant-garde. Hans Hollein, Walter Pichler, Haus Rucker Co., and Coop Himmelb(l)au all experimented with pneumatics, calling for new structures and materials to extend architecture beyond its traditional constraints.

The Mobile Office (1969) was an “invisible”, collapsible workspace that could be carried around and set up virtually anywhere. In an interesting precursor to today′s understanding of the mobile workspace, Hollein is seen here in his “office” with drawing board and telephone in hand, at an airport stopover delivering “architecture” to a client.

Though inflatable architecture provided a mental leap in moving “beyond pure tectonic building and its derivations”, Hollein still considered them to be building materials and called for further experimentation with entirely nonmaterial means.![]() (ssl)

(ssl)![]()

Hans Hollein inside his mobile inflatable office, 1969. (Photo © Atelier Hollein)

-

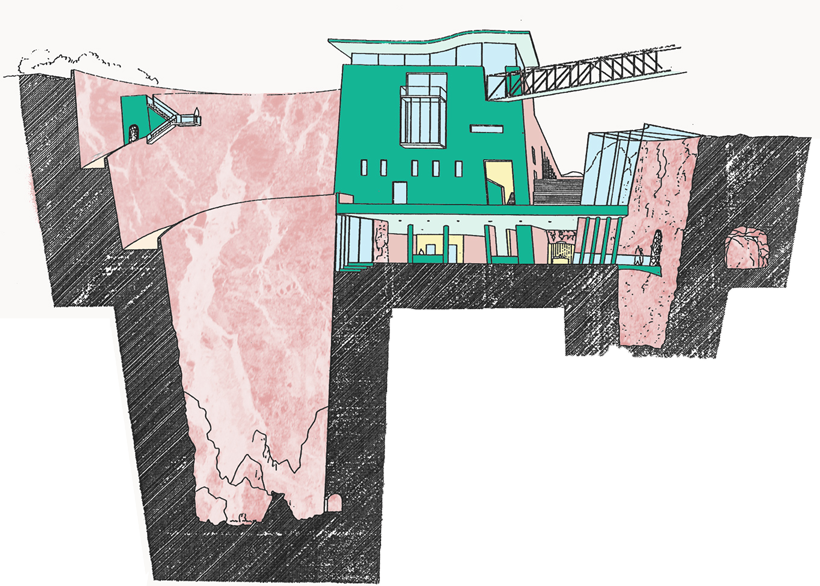

![]()

Location: Tehran, Iran

Build: 1977-1978Illustration: Madalena Boavida Guerra‚ based on axonometric by Hans Hollein

-

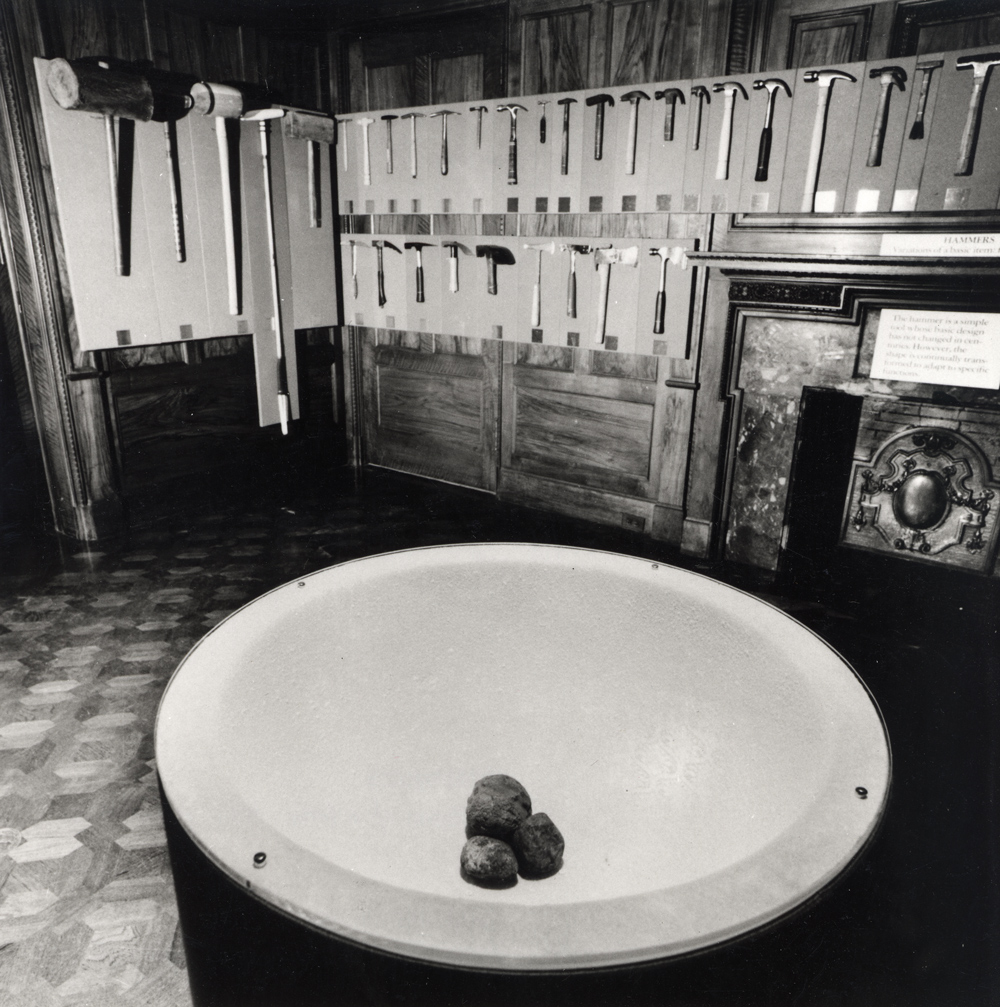

Hans Hollein’s solution for adapting a small 19th century palace into a museum of glass and ceramics, was to design a series of highly sculptural display cases – allowing preservation of the original interior fabric whilst adding his own highly distinctive signature to the building.

With their strong geometric vertical forms, looking like variations on abstracted columns, these polished stainless steel and chrome vitrines contrast strongly with the delicate interior plasterwork, with its mix of European Beaux-Art and Iranian detailing.

Through the design of these display cases, Hollein intended visitors to be “confronted emotionally by the objects and their quality as works of art”. Together they form an exhibition landscape, providing a dramaturgy through the collections, beginning outdoors with a single case embedded in a brick wall, leading inside to striking groupings of the free standing units, with other cases set into the parquet floors.![]() (rgw)

(rgw)Photo © Hans Hollein archive

-

![]()

Hollein as designer-curator

Exhibition-making and curating formed a key strand in Hans Hollein’s practice. They allowed him to experiment in concentrated form with his most radical ideas on architecture as a medium of communication. For the Austriennale in 1968, he presented and packaged Austria and its culture as products behind a series of doors in narrow corridors, which created for visitors an intense experiential and spatial engagement with the material on show. With his curation and design for the Cooper Hewitt Museum’s opening display, MANtransFORMS, in New York in 1974, Hollein presented an anthropological history of design not just as man’s transformation of material into design object, but as the metamorphosis of humans into designed social beings. Exhibitions enabled Hollein to play with objects, displacing them from one environment to another, mixing scales and materials: creating meaning, beyond function, through juxtaposition and context. As such he was postmodern before his time, and he went on to produce, in the columned façade he designed as part of Paolo Portoghesi’s exhibition Strada Novissima at the Venice Architecture Biennale in 1980, an iconic call to arms for the spirit of Po-Mo architecture. (rgw)

-

![]()

Strada Novissima, “The Presence of the Past” exhibition, Venice Biennale, 1980. (Image courtesy MMK)

![]()

“MANtransFORMS”, 1974. (Photo © Murray Grigor, courtesy Hans Hollein archive)

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

“MANtransFORMS”, 1974. (All photos © Murray Grigor, courtesy Hans Hollein archive)

-

![]()

![]()

“Austrienale”, Austria’s contribution to the 14th Triennale di Milano, 1968. (All photos © Christian Skrein, courtesy Hans Hollein archive)

-

![]()

Location: Mönchengladbach, Germany

Build: 1976-82Illustration: Madalena Boavida Guerra‚ based on axonometric by Hans Hollein

-

For this museum, which was Hans Hollein’s first, he designed not just the building but all aspects of the interior design – from wall panelling to lighting to furniture: a gesamtkunstwerk in the spirit of early Viennese modernism.

Internally, as opposed to a classical enfilade of galleries, its radical cross-connecting spaces were developed in response to the fluid curatorial concept of director John Cladders. Externally it does not have a single traditional monumental “museum” form but is bedded down into the landscape of the city, its elevated position on a hill softened by stepped landscaping inspired by rice terraces, whilst its tower and sandstone cladding echo that of the cathedral and local parish church, and the gallery “shed” forms reference the textile factory buildings of a city once known as the “Rhenish Manchester”.![]() (rgw)

(rgw)Photo © Marlies Darsow, courtesy Hans Hollein archive

-

![]()

SBF Tower

This project for a 42-storey, 200-metre-tall office tower, currently under construction, draws upon Hollein’s early ideas whilst signifying the future of his office. In 2009, Hans Hollein & Partner won a competition to develop a tower in the new Central Business District of Shenzhen. It is prominently sited, adjacent to the intersection of the main city axes and across from the Stock Exchange building designed by OMA.

During the design development, practice partner Christoph Monschein suggested they take inspiration from Hollein’s sketches for high-rises that he made in Chicago (where he trained with Mies van der Rohe) in 1958. One of these forms the basis of the present design, in which highly articulated five-storey sections are interspersed as bands up the shaft. Each one is a complex interplay of recesses, set-backs, cantilivers and extrusions, forming terraces, balconies and hanging gardens, and providing stark contrast to the smooth abstracted grid of the adjacent buildings.

![]() (rgw)

(rgw)Hans Hollein conjuring up his SBF Tower. (Photo © Hans Hollein archive)

-

![]()

-

Philip Beesley, "Hylozoic Soil", Espacio Madrid, 2012. (Photo © PBAI)

![]()

Issue No. 25

August 28th 2014

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Intelligence starts with improvisation.«

Yona Friedman

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents

shelter at all,

shelter at all,