-

Magazine No. 26

School′s Out

-

No. 26 - School´s Out

-

page 02

Cover

School´s Out

-

page 03

Editorial

School's Out

-

page 05 - 14

No More Masters

Interview with Odile Decq

-

page 16

Education as Practice

Rural Studio, Auburn

-

page 17

Education as Network

Aedes Network Campus, Berlin

-

page 18 - 24

Radical Pedagogies

Architectural education in times of disciplinary instability

-

page 25

Education as Anarchy

Dirty Art Department, Amsterdam

-

page 26

Education as Accident

SCI-Arc, Los Angeles

-

page 27 - 34

Buildings to Learn In, Buildings to Learn From

Visiting two recently designed architecture schools in Nantes and Tirana

-

page 36 - 39

Zumtobel Group Award

Winners!

-

page 40 - 45

License to Think

Interview with Eugenie deLariviere

-

page 46

Education as Curation

AA Night School, London

-

page 47

Education as Branding

Strelka Institute, Moscow

-

page 48 - 53

Deschooling Society

Learning in the networked era

-

page 54

Education as Open Platform

The Public School for Architecture, Brussels

-

page 55 - 57

Bookmarked

Eugene Asse

-

page 58

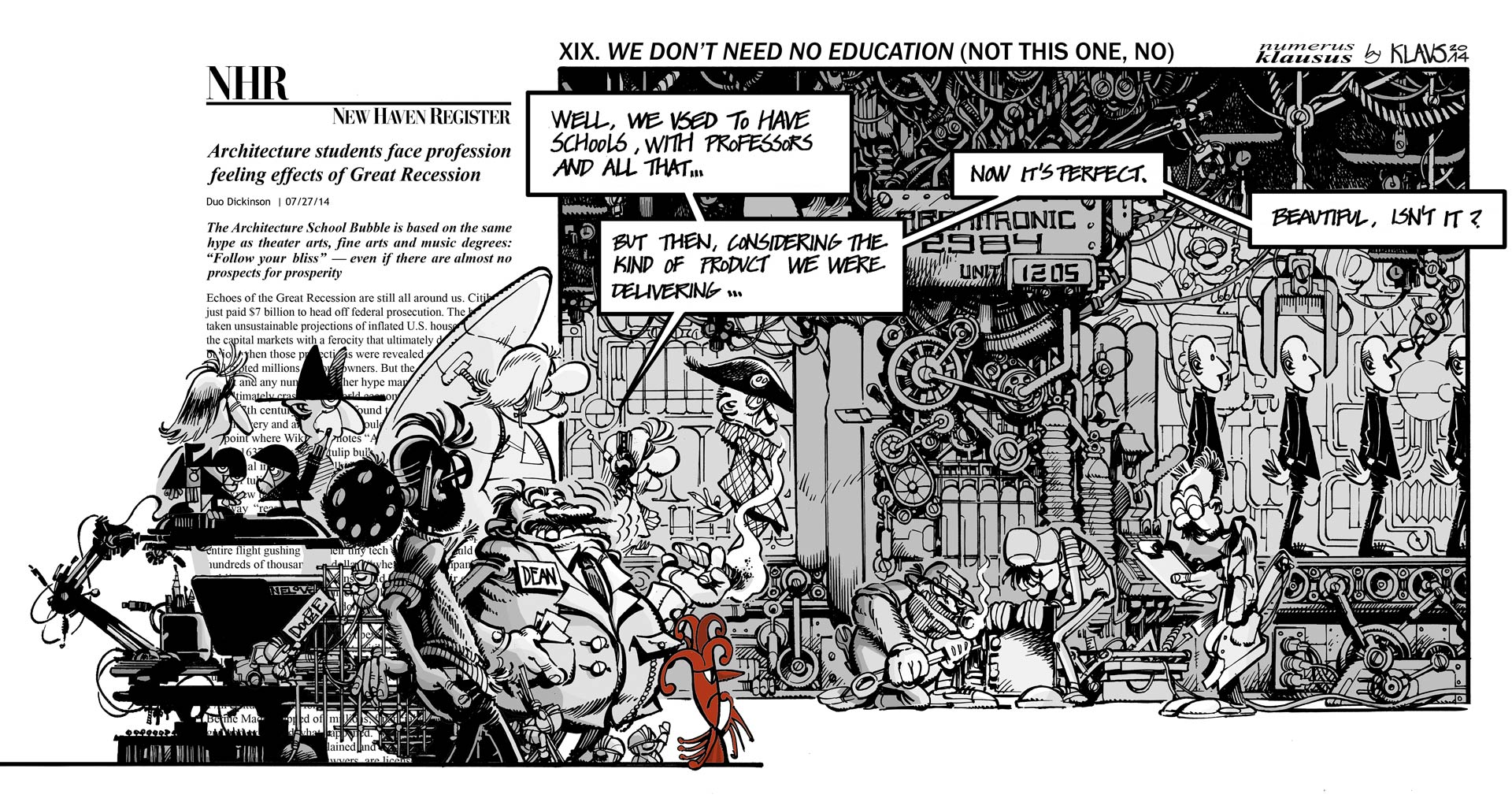

Klaustoon

XIX. We Don't Need No Education

-

page 59

Next

Australia

-

-

uncube’s editors are Sophie Lovell (Art Director, Editor-in-Chief), Florian Heilmeyer, Rob Wilson and Elvia Wilk; editorial assistance: Susie S. Lee, Leigh Theodore Vlassis and Fiona Shipwright; graphic design: Lena Giovanazzi; graphics assistance: Madalena Guerra. uncube is based in Berlin and is published by BauNetz, Germany's most-read online portal covering architecture in a thoughtful way since 1996.

In the wake of the Bologna Process, most European architecture schools are struggling to conform with the standardised educational models now required – not to mention rising costs, outdated bureaucracies and a rapidly changing profession. Today, most architecture graduates won’t even become architects. Can architecture education catch up with reality?

This issue of uncube tackles the complicated status quo, with a focus on the European continent but an eye on the rest of the world. After talking to experts and experimenters across the board, there’s only one thing everyone can agree on: the system needs a serious overhaul.

We’ve done our homework – now it’s your turn!![]()

![]()

![]()

Cover photo and this page: Jan Pieter Kaptein‚ “The Second Self Laboratory”‚ graduation project Design Academy Eindhoven, 2013. (Photo: Lisa Klappe)

-

No More Masters

Interview with Odile Decq

by Florian Heilmeyer

Illustrations by James Kerr -

![]() rchitect and educator Odile Decq taught for 20 years at the École Spéciale d’Architecture (ESA) in Paris. Decq was dean of the university from 2007 until she resigned in 2012, when she found it impossible to implement the institutional reforms she felt necessary for teaching architecture students in today’s world. This autumn sees the opening of her new private university in Lyon, the Confluence Institute for Innovation and Creative Strategies in Architecture‚ where she hopes her reforms will be realised. In attempting to break the mould, Decq’s “Confluence” has already drawn as much criticism as it has praise. uncube asked her to elucidate her plans and explain where she thinks architecture education needs to go.

rchitect and educator Odile Decq taught for 20 years at the École Spéciale d’Architecture (ESA) in Paris. Decq was dean of the university from 2007 until she resigned in 2012, when she found it impossible to implement the institutional reforms she felt necessary for teaching architecture students in today’s world. This autumn sees the opening of her new private university in Lyon, the Confluence Institute for Innovation and Creative Strategies in Architecture‚ where she hopes her reforms will be realised. In attempting to break the mould, Decq’s “Confluence” has already drawn as much criticism as it has praise. uncube asked her to elucidate her plans and explain where she thinks architecture education needs to go.Madame Decq, the very first sentence of the mission statement for your new architecture school is: “We believe that today it is fundamental to totally rethink architecture education.” Why? What is wrong with existing models?

It′s not so much a question of what is wrong or not. It is rather that the world has changed dramatically and so too has the profession of architecture – and ultimately architecture itself. The only things that have not changed are the models for architecture education, which have not only proved very rigid and un-reformable but in Europe, due to the Bologna Process, they have been made even more inflexible in favour of a general bureaucratic compatibility and homogeneity. This is a serious problem for the variety of existing models. That’s why I think that we really have to fundamentally rethink architecture education – and that′s why it is so exciting to start a new architecture school now.

-

»When we are in a state of crisis like we are today, we have to rethink the world.«

-

How would you describe the predominant model of architecture education today?

I have taught at a lot of institutions over the last 20 years including SCI-Arc, Bartlett, Columbia, the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna and Düsseldorf or the IUE in Madrid. I was sort of “analysing” the existing models from within and I found that these very different institutions are all trapped within the existing system. They either teach about designing architecture, with all these pointless discussions about forms and objects and very formal approaches, or they try to educate the students to become efficient, well-functioning professionals. It seems that around the beginning of the 1980s architecture schools started to focus more and more on building and designing objects instead of teaching architecture.

This, together with the rise of the starchitect, has worsened to the point that today many people think of architecture only as a discipline that produces shiny, spectacular objects. Yet architecture is a discipline that requires a deep cultural, sociological, economical, political and ethical understanding of the world. This is what students need to learn because, when we are in a state of crisis like we are today, we have to rethink the world. We have to act differently, which means that we have to look beyond building too; to help people and improve living conditions for mankind and this sometimes requires something different from a building. At our new school, we don’t subtract anything from the usual architecture education. Students will still learn how to build. But we add other topics in order to broaden the picture. -

This harks back to the 1970s when many institutions started to add subjects like sociology and economics to their curriculums. Are you suggesting reconnecting architecture education to these models?

To me it is crucial to bring all the disciplines related to architecture together. Instead of separating them into specialised disciplines we need to create one space where students all come and study with one another and only at the end decide what they want to be as professionals. Indeed I believe that education in the late 1960s and early 1970s was much more open and reflective about its own models. But we have to develop these models further in order to meet the demands of our times. That’s why for the curriculum at the Confluence, we have defined five thematic fields including “Neurosciences”, “Visual Art” and “Social Action”. Sociology was indeed a new topic in the 1970s at a time when many people thought “why would an architect need to know about sociology?”

Today this is a common ground, of course architects need to know about the society within and for which they are building. But architecture should not only analyse society, it should act within society too. We have to take a critical position and we have to take risks! It really frightens me when I notice that younger people are afraid of taking risks or of having their own position.

How do you teach this?

I strongly believe that architecture is about the human being. Very fundamentally the duty of an architect is to provide human beings with a shelter and to continuously improve living conditions. This is why I am so much against the starchitecture system, and against the understanding of architecture as an object. If you take a look at the generation of architects under 40 today, many of them are already involved in this model of “social action”. They are acting in communities, developing projects directly with neighbours and activists. This is something our educational models need to react to.

-

If you create a new architecture school, then it raises the question of appropriate spaces. How did you design the Confluence?

The best space to teach architecture in is a simple box. When I look at some of the latest buildings for art or architecture schools, I must say that they are too designed. When architects design a school for architecture, they tend to turn it into a statement and the students are then trapped within this architecture. I think spaces like at SCI-Arc are perfect for education. Theirs is an industrial building from the twentieth century, basically a long rectangular box with a raw and robust interior continuously transformed by the students. We tried to create our new building in the structure of an old market building for the Confluence in a similar manner: it has three large surfaces stacked on top of each other offering very open spaces that can be re-arranged and re-organised in many different ways. The only specific spaces are in the basement where there are all the machines and workshops. We are also trying to create connections with the city and the people of Lyon as much as possible. The ground floor is very transparent and open. We’ll have our lectures and exhibitions there, inviting people and passers-by in from the outside.

»The best space to teach architecture in is a simple box.«

-

SCI-Arc in Los Angeles was also founded as an alternative education model in its time yet has meanwhile become an established institution. Have you considered why schools become “institutionalised”? Is there a way to prevent that happening to Confluence in the future – getting stalled in its own fixed system?

I really don’t know. It is of course a very interesting process: how institutions are born and what becomes of them over time. Even the Ecole Spéciale in Paris was founded by Viollet-le-Duc in 1865 explicitly as an alternative model. Maybe it is just not so much about being against or outside the existing system. It’s about offering alternatives. I believe its better to have niches alongside the mainstream in order to create options to choose from.

What about finances? You have been accused of being mercantile and elitist with fees projected to be 12,000 Euro a year…

We don’t mean to be elitist or exclusive in any way. Yet the Confluence is a private institution and we want to stay a little school, so I cannot reduce the costs by having more students. And in order to finance the quality that we want to achieve, we simply need money.

Basically in France everyone assumes that the state has to take care of education on all levels. That’s also why we have been under attack from some public schools and the French Syndicat de l’Architecture for founding a private institution. In France, everything that is “private” is always immediately seen as elitist. But to be honest I just don’t understand this question. -

Odile Decq set up her own office just after graduating from La Villette in 1978 while studying at the Sciences Politiques Paris where she completed a post-graduate diploma in Urban Planning in 1979. International renown came quickly; as early as 1990 she won her first major commission: the Banque Populaire de l’Ouest in Rennes which was recognised with numerous prizes and publications. She was awarded a Golden Lion in Venice in 1996. Since then, Odile Decq has remained faithful to her fighting attitude while diversifying and radicalising her research.

Recently, she has completed the MACRO (Museum for Contemporary Art in Rome) in 2010, the Opera Garnier’s restaurant in Paris in 2011, the FRAC (Museum of Contemporary Art in Rennes) in 2012 and has just completed the GL Events headquarters in Lyon.

odiledecq.com

confluence.eu

With this wide range of fields to study, what will the experience be like for the students?

By staying a very small school we can ensure that there is someone to look after each student individually and help him or her develop their own interests, specialisations and in the end an orientation for how to continue. One of the main problems with existing models is that individuality, which is so important to an open society, is getting lost in the bureaucracy that tries to homogenise the people as much as possible only in order to make them administrate-able.

Is this then a very personal model, with one main tutor/teacher that guides each student through their studies?

No. I don’t believe in the idea of a maestro, that you have one personal teacher and you follow him. I absolutely reject that. There should always be different people and different opinions, especially contradictory ones. Maybe this confrontation with many opinions doesn’t make learning easier. But it helps you to define your own position and opinion. Then you are not a follower anymore. You are independent and can in the end decide what you want to do and what you want to be. Maybe even an architect. p

-

Education as Practice

Rural Studio, Auburn

Rural Studio is seen as the ur-example of practical hands-on undergraduate architecture courses. Set up by D.K. Ruth and Samuel Mockbee in 1993 as an off-campus design and build programme of the School of Architecture in Auburn, Alabama, its students make 1:1 architecture – not just radical, experimental structures that last a summer – but practical, useful buildings and real homes. They’ve constructed more than 150 structures at the last count for the local community of Hale County. From its foundation, the course established an ongoing ethos of recycling and reuse of materials, and each project starts with the premise of “what should be built, rather than what can be built”, a test of need that has seen a town hall, bathhouse, museum, skate park, animal shelter and church constructed in a relatively poor and underserved rural neighbourhood. p (rgw)

ruralstudio.org“Dave′s House”‚ 2009. (Photo © Tim Hursley)

-

![]()

Education as Network

Aedes Network Campus, BerlinAedes Network Campus Berlin (ANCB) is a “metropolitan laboratory” and public platform for contemporary urban discourse. Founded in 2009, it grew out of the experience and international network of Aedes Architecture Forum, a private institution that has been presenting contemporary architecture for public discussion for 35 years. In a range of formats from conferences to university design workshops, global urban challenges such as mobility, resource consumption and housing are negotiated with a broader public audience as well as with other disciplines. ANCB actively connects different academic institutions, experts from various professions and partners from the industry while also making the working process and results of the events and workshops publicly accessible in exhibitions, discussions, publications and a collective archive. The idea is that students and professionals alike can benefit from the cross-pollinating environment and programme that the campus provides outside of institutional restraints. p (fh)

Participants of The Why Factory (TU Delft design studio with Winy Maas) in the ANCB garden. (Photo: ANCB The Metropolitan Laboratory)

-

Radical

PedagogiesArchitectural education in times of disciplinary instability

The nomadic school “Global Tools” was founded in Italy‚ 1973‚ by members of the Radical movement. This image shows a performance by Superstudio at a Global Tools meeting in Sambuca Val di Pesa, Florence, in 1974. From left to right: Angiolino Lepri, Adolfo Natalini, Fabrizio Natalini, Roberto Magris, Gino Lepri, and Cristiano Toraldo di Francia. (Image courtesy Adolfo Natalini)

-

![]()

![]()

The ongoing Radical Pedagogies research and exhibition project, first presented in 2013 at the Lisbon Triennale and then developed for the 2014 Venice Biennale, explores a series of pedagogical experiments that played a crucial role in shaping architectural discourse and practice in the second half of the twentieth century. Operating as small endeavours, sometimes on the fringes of institutions, these experiments questioned, redefined, and reshaped the post-war field of architecture and challenged normative thinking. Much of architecture teaching today still rests on the paradigms they introduced. uncube asked the project’s research collective to choose their five favourite radical pedagogies.

Giancarlo de Carlo debates with Gianemilio Simonetti as protesting students take over the Milan Triennale in May 1968. (Photo: Cesare Colombo)

-

![]()

Global Tools

Florence and Milan, Italy (1973–1975)

—

Active from 1973 to 1975 and founded by the members of the Radical movement, the nomadic school Global Tools explored architecture as a primordial creative act. As a nomadic school, Global Tools was founded in the editorial office of the magazine Casabella at the beginning of 1973. The collaborative project and magazine of the same name replaced the urban installations of late 1960s Florence with “didactic laboratories” open only to its members. Challenging the more canonical understanding of architectural pedagogies, the group’s aim was to learn from the “archaic wisdom” of the uomo de-intellettualizzato, or de-intellectualised man.

The focus was on artisanal methods of production, the employment of “poor” materials, and the ritual aspect of using handcrafted objects. As an alternative to industrial methods, handcrafted production offered a way to rethink the act of both conceiving and making an object. What was at stake was the generative act of production at large and the industrialised systems that they wished to overhaul. For Global Tools, the central task for architectural education was to ask why and how humans instinctually create. p (Federica Vannucchi)

![]()

“The Body and its Restraints”, Global Tools performance by Franco Raggi‚ Gruppo Corpo‚ Milan 1975; from Casabella 411 (1975).

-

![]()

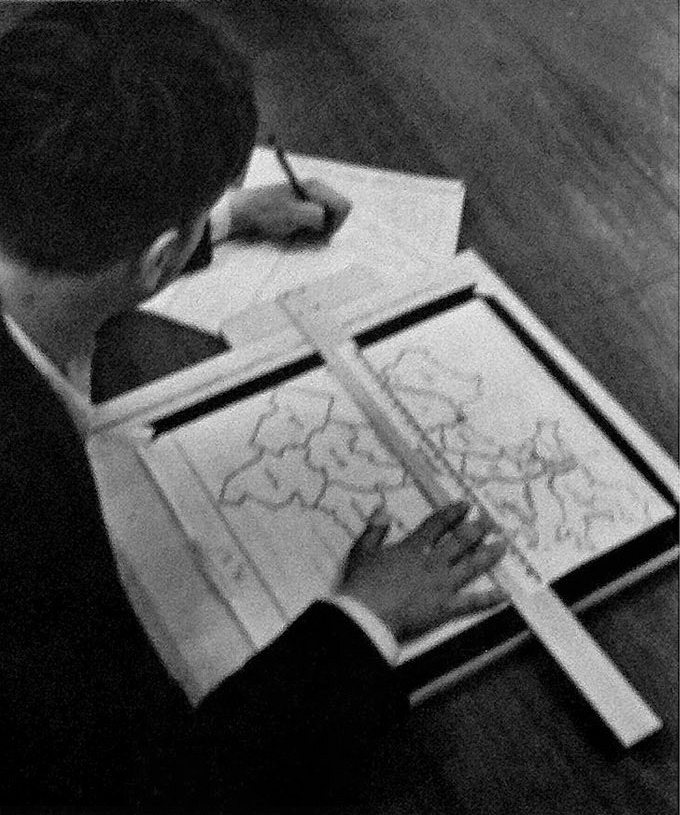

The Laboratory for Computer Graphics and Spatial Analysis (LCGSA)

Harvard GSD, Cambridge MA, USA (1964 –1984)

—

The Laboratory for Computer Graphics and Spatial Analysis at Harvard GSD (LCGSA) was one of the first radical, long-lasting institutions to introduce the computer as a tool across all the design disciplines. It operated as part of the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) between 1965 and 1991. Initially affiliated with the department of Regional and City Planning, it was founded by Howard Fisher as an experimental venue for the use of computers in the creation of maps. The lab also conducted courses, workshops and conferences. Despite the technical advances with which it is often credited (such as the “invention of GIS”) the pedagogical innovations of the LCGSA have been often overlooked.

The LCGSA members included architects, geographers, cartographers, mathematicians, computer scientists and artists. They believed that computer use in academic settings could profoundly alter the ways in which design disciplines operated. Alongside its ground-breaking and multi-faceted work, the lab’s experiments consistently raised questions about the practical ways in which computing could be of immediate relevance to the education of young designers, especially architects. p (Evangelos Kotsioris)![]()

LCGSA student going through the steps of creating a computer map with the SYMAP programme.

-

![]()

Learning from Levittown Studio

School of Architecture, Yale University, Connecticut, USA (1970)

—

The “Learning from Levittown” studio course taught by Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi was radical not only in form, but in teaching content as well. It applied the innovative and collaborative “learning from” style of pedagogy for students to explore the world of suburbia. Following their “Learning from Las Vegas” studio in 1968, Scott Brown and Venturi conducted this studio in the spring of 1970. Venturi recalls the scandal that arose during the class final review: “We forget how much suburbia was despised at the time by the idealists”.

Scott Brown and Venturi treated architecture as a form of media. The course focused on how the inhabitants of Levittown decorated the exteriors of their own houses and also the way in which houses were represented in television commercials, home journals, car advertisements, cartoons, films, and even soap operas.

The course took place during a time of both urban and educational unrest. In the spring of 1970, there were big protests in New Haven: The Black Panther trials were in progress and there were riots in the city and rallies at Yale. The School of Architecture building was burned down, allegedly by students, the spring before, so the studio had to be held in a provisional building. p (Beatriz Colomina)![]()

The Architecture School at Yale University was burnt down‚ allegedly by students‚ in 1969.

-

![]()

Hochschule für Gestaltung (HfG) Ulm

Ulm, Germany (1953–1968)

—

Moving off the grid both geographically and ideologically in 1953, the founders of the Hochschule für Gestaltung (HfG) in Ulm hoped to create a fundamentally different approach to design education that could re-democratise Germany after the war. Their highly rationalist approach was rooted in humanist functionalism aiming for “good design” to improve society. The HfG saw itself as an institution of dissidence in a country that was myopically rebuilding its cities yet failing to engage critically with its past. The school not only reformed architectural pedagogy but treated architecture as scaleless object of design – no distinction was made between shaping buildings and forming teacups or stools.

Expanding the Bauhaus notion of placing architecture at the centre of its curriculum, the HfG ultimately designed the design process itself. For this “process design”, the school set up its curriculum with theory and practice as equal parts, inviting mathematicians, sociologists, writers, and philosophers for guest lectures and seminars. Despite the school’s dedication to experimentation, its protagonists firmly believed in institutional frameworks for such explorations. Their experimentation created a paper trail – the meetings and institutionalised debates questioning pedagogy were transcribed, typed with several carbon copies, disseminated, and filed. In Ulm, radicality was institutionalised, or rather, institutionality was radicalised. p (Anna-Maria Meister)

![]()

![]()

Top: Reyner Banham (left) with Tomas Maldonado at the HfG in 1959. Bottom: Charles Eames (right) in conversation with Max Bill at the HfG in 1955. (Photos: HfG-Archiv‚ Ulmer Museum)

-

Architectural education in a time of disciplinary instability is the research topic of Radical Pedagogies. It is an ongoing collaborative research project set up by Beatriz Colomina together with PhD students at the Princeton University School of Architecture where she teaches architecture history and theory. Radical Pedagogies focuses on radically new models and experiments in architecture education in the second half of the 20th century. So far it has involved three years of seminars, interviews, archival research, guest lectures and contributions by protagonists and scholars from around the world. Currently on show as a part of the Monditalia section at the 14th International Architecture Biennale in Venice, it has been awarded with a Special Mention.

![]()

Escuela y Instituto de Arquitectura

Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Chile (1952–1972)

—

The Valparaiso Architecture School offered both an elaboration on the intellectual project of modernity and a response to modern architecture. Led by the Chilean architect Alberto Cruz and Argentinean poet Godofredo Iommi, its pedagogy drew from a wide set of references within the avant-garde. Exercises initially pursued plastic explorations, which were developed through "poetic acts" and the so-called phalanes – which oscillated between public recitations of poetry and collective artistic performances including games, garments and other plastic manifestations. The phalanes were intended to load spaces with meaning and open them to the creation of new subjectivities. They questioned any “instrumentalisation” of architecture, dismissing the modern emphasis to "change the world" to pursue instead a “change of life”.

This pursuit obliterated the boundaries between learning, working and living, in a destabilisation of pedagogical structures that eventually led students and faculty taking over the school in 1967. Their protests against the university authorities resonated with those that shook institutions globally one year later, though the School members set themselves apart from the political emphasis of the 1968 revolts. In Valparaiso, this destabilisation of the university ultimately resulted in the foundation of the experimental living and working space Open City, which was built by students and faculty starting in 1971 to further test the boundaries of architecture. p (Ignacio González Galán)

Tournaments in the course “Culture of the Body”‚ 1975. (Photo: Archivo Histórico Jose Vial)

-

Education as Anarchy

Dirty Art Department, AmsterdamFive years ago the Sandberg Instituut invited designer Jerszy Seymour to set up a new post-grad programme in Applied Arts to challenge students to “critically question the discourses structuring the field of art and design” and “engage with social reality as hybrid artist-designers”. Inspired by radical school projects of the past Seymour responded by founding the Dirty Art Department in 2011 together with Catherine Geel, Clémence Seilles and Stephane Barbier-Bouvet as a launch pad for people and ideas. “[It is] concerned with individuality, collectivity, and our navigation of the complex relationship between the built world, the natural world and other people and ourselves”, says Seymour. The 22 course students spend two years on a magical mystery tour that questions just about every convention. Last spring they and the teaching staff squatted a building where they can now live, work, party and exhibit.

Seymour wants to stop the course after five to six years before it turns into “dogma and an institution of itself”. “The dirty art department will blow up in a hot cool gentle explosion and transfer into something else” he adds, “perhaps after the autonomous building we go to the autonomous land, grow vegetables, rear some goats, grow our hair long, fuck each other, give up art and education and live happily ever after.” Long live the commune. p (sl)All in a day′s work at the Dirty Art Department‚ 2012. (Photo: David Bernstein)

-

![]()

Education as Accident

SCI–Arc, Los AngelesSpontaneously founded in 1972 in a warehouse in Santa Monica, California by a small group of liberal educators and students, SCI-Arc – now one of the world's most highly rated architecture education institutions – developed a brand-new form of pedagogy almost by accident. Rejecting the established institutional models of the time, SCI-Arc - originally called the New School - advocated an unbiased, non-hierarchical learning environment where students, educators and administration could work together on an even platform.

That was then; this is now. With a newly appointed director – Hernan Diaz Alonso – the first in over a decade‚ SCI-Arc remains an ever-evolving learning institution bringing together approximately 500 students and 80 faculty members under one very large roof. Now located in a 400-metre-long former freight depot on the east side of downtown Los Angeles, SCI-Arc remains true to its original inceptors′ ideologies, and is still purportedly non-hierarchical. There is a drawback however: despite the lateral learning situation, the fees are anything but egalitarian. Current full-time enrollment for one semester will set you back a very cool 20,131 USD. p (ltv)The students′ studio spaces fit within and follow the building′s preexisting structure. (Photo courtesy SCI-Arc)

-

Buildings

to Learn in![]()

Buildings

to Learn FromVisiting two recently designed architecture schools in Nantes and Tirana

By Andreas Ruby

(Photo: Simon Menges‚ courtesy Holcim Foundation)

-

What’s in a school, who should it serve and how? Architecture critic and publisher Andreas Ruby weighs up the pros and cons of an architecture school building conceived as a didactic tool vs. a functional blank canvas with two recent projects in France and Albania.

You would think that designing an architecture school would be a dream project for any architect, but actually it is quite tricky since a decision needs to be made quite early on about whether the building should be a place to learn in or also to learn from. The latter option seems a natural choice – to use the building as a didactic device and design it as a showcase for good architecture. But then, ideas of what is good and beautiful have a tendency to change over time – just think of the eighties. Thus an architecture school intended to represent the crème de la crème of the discipline can easily wind up as a period piece, a functional mess and aesthetic embarrassment for those who have to study in that building for decades to come.

So there are good reasons to discharge an architecture school building of any didactic mission and conceive it simply as a spatial enabler of educational activities, nothing more, nothing less. But is that even possible? Can an architect make a building that is not a statement in one way or another? Let’s look at two recent architecture school projects that represent opposing approaches. For brevity’s sake let’s call them the “cool” and the “hot”.

-

The cool

The École d’Architecture de Nantes by Lacaton & Vassal, completed in 2009, is a prime example of the cool attitude. The architects have no didactic mission to tell, but use a very basic observation as their starting point: the fact that every architecture school they knew invariably runs out of space quickly. Hence they simply multiplied the surface area defined in the competition brief by the factor two, complementing the required programme area to absorb any future spatial needs. To achieve this considerable extension without exceeding the given budget they use a type of construction normally used for parking garages: an arrangement of extra strong concrete floor plates (1000 kg/m² load capacity) and generous ceiling heights between seven and 12 metres.

This primary structure is partially filled with smaller volumes housing each programme, while the remaining free space is left unprogrammed. If this building has any architectural message to the students, it is “Use me!” It does not give a catalogue of solutions as to how to work with different materials nor does it revel in the fetish of daring details. Lacaton & Vassal obviously see the value of architecture less in the object of the building and more in the spectrum of appropriations that it enables.

![]()

(Photos: Simon Menges, courtesy Holcim Foundation and Paul Raftery)

![]() The school follows a type of construction normally used for parking garages. (Photo: Philippe Ruault)

The school follows a type of construction normally used for parking garages. (Photo: Philippe Ruault) -

»If this building has any architectural message to the students, it is: Use me!«

Movable transparent façade panels allow light to enter into the building, increasing usability of the space inside. (Photo: Simon Menges, courtesy Holcim Foundation)

-

![]()

Whilst the Epoka ground floor (hot) has a rather conventional organisation of learning spaces (Image © Zambak/CoRDA), the architecture school in Nantes (cool) offers a wide open floor plan with unspecialised, robust spaces, some double height, leaving it (almost) completely up to the teachers and students in how they want to use or combine them. (Image © Lacaton & Vassal)

-

The Hot

The hot attitude is perfectly illustrated by the recently completed Epoka University Student Centre in Tirana, Albania. The project was actually designed in two phases and by two different teams. The general concept of the building was made by the Istanbul-based office Zambak, but the entire interior architectural design and detailing was done by CoRDA, the school’s own architecture office. It is run by a number of professors from the faculty who, together with students and recent graduates, do actual construction projects as part of the school’s educational curriculum. In other words, this architecture school was designed by the very people who work in it. CoRDA used this unique opportunity to turn the building into an architectural treatise featuring commendable architectural techniques for the students to learn from.

![]()

A tour around the Epoka University Student Center in Tirana, Albania. (Photos: Eduard Pagria)

![]()

The interior spaces of Epoka serve as an educational tool for its architecture students, featuring various commendable building techniques and architectural styles, turning the building itself into a 1:1 model and exhibition about architecture. (Photo: Andreas Ruby) -

»Ideas of what is good and beautiful have a tendency to change over time – just think of the eighties.«

Meant as a “Building to learn from”, the architecture school in Tirana features different patterns in its marble floor, which are flat and spatial. It also demonstrates different techniques of masonry within its brick walls. (Photo: Eduard Pagria)

-

Andreas Ruby is an architecture critic, curator, moderator, teacher and publisher. He has taught architectural theory and design at a number of institutions worldwide including: Cornell University, École Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture Paris Malaquais, the Metropolis Program Barcelona and Umea School of Architecture. Aside from his contributions to selected international architecture magazines, he has published nearly 20 books on contemporary architecture. In 2008 he co-founded the architecture publishing house Ruby Press.

ruby-press.com

The images of the Architecture School in Nantes by Simon Menges were shot for the publication University building in France – Nantes School of Architecture, edited by Ilka & Andreas Ruby, pub. Holcim Foundation, Zürich, 2011.

holcimfoundation.org

For instance, the floor of the main hall is realised in coloured pieces of marble laid out in figurative patterns, which oscillate between flat and spatial effects, depending on where you stand – a kind of Escher for beginners. The interior walls are made of bricks laid in various ways to expose all their different faces to the viewer. Thus you actually get to see the brick as a three-dimensional object, which in turn transforms the wall into an exciting plastic relief. Other details of the building, such as doors, suspended ceilings and windows, are treated as examples of how to design and build those elements. This didactic approach makes particular sense in a country such as Albania, where there are not a lot of architecturally outstanding public buildings that students could learn from. Completed in 2013 the building is already a landmark of contemporary architecture and has garnered international attention through publications and awards.

These examples seem to suggest that there is no set rule as to whether an architecture school building should be hot or cool; it depends in many ways on the physical and educational context of the school. Both buildings discussed here make perfect sense in their respective environments, and their polarity is inspiring. Maybe the two establishments should exchange their students and faculties each year for a detox summer school? p -

International Conference on Architectural Education

State Academy of Art and Design Stuttgart:

www.weissenhof-institut.abk-stuttgart.de

GIF design: Ute Müller-Schlösser / Christian Nicolaus

-

The Zumtobel Group Award: Innovations for Sustainability and Humanity in the Built Environment promotes social, technical, and environmental responsibility by rewarding innovative endeavours. Over the last three months, in collaboration with Zumtobel AG, uncube has been presenting the best of the shortlisted candidates in each of the 2014 award’s three categories: Initiatives and Applied Innovations, Buildings and Urban Developments, and this month we announce the winners, who each receive a prize of €50,000.

On September 22, 2014 the international expert jury announced selected projects from Arup of Germany, Studio Tamassociati of Italy and Elemental of Chile as the winners in the respective categories. The jury initially selected 15 projects as nominees from among 356 submissions for the award – which was curated by Aedes Architecture Forum in Berlin. The winning projects are marked by their innovative and ground-breaking character. “Voting to find the number one project was very close in all three categories,” said the chairman of the jury, Winy Maas. “A key criterion for the jury this year was innovation, technically but also in planning and participation processes and in ecological and social challenges.”The expert jury panel for the Zumtobel Group Award 2014 included:

Kunlé Adeyemi – Architect & Urbanist / Founder NLÉ, Amsterdam (NL)

Yung Ho Chang – Architect / Studio FCJZ, Beijing (CN)

Brian Cody – Chair of the Institute of Buildings and Energy, Graz University of Technology (AT)

Winy Maas – Architect / MVRDV, Rotterdam (NL)

Ulrich Schumacher – CEO Zumtobel Group

Kazuyo Sejima – Architect / SANAA, Tokyo (JP)

Rainer Walz – Head of the Competence Center Sustainability and Infrastructure Systems at the Fraunhofer Institute for Systems and Innovation Research ISI in Karlsruhe

![]()

![]()

Chosen by the jury: Winy Maas, Kazuyo Sejima, Kunlé Adeyemi, Yung Ho Chang, Brian Cody, Rainer Walz and Ulrich Schumacher

-

In March 2013 the BIQ, a four-storey residential building designed by SPLITTERWERK architects, was completed as part of the International Building Exhibition (IBA) in Hamburg. It showcases the first Solar-Leaf façade: a building integrated system absorbing CO2 emissions, while cultivating microalgae to generate biomass and heat as renewable energy resources. The environment for photosynthesis is provided by glass photobioreactors installed on the southwest and southeast elevations. The façade has three main benefits: a) Generation of high-quality biomass for energetic use or as a resource for food and pharmaceutical industry (urban farming); b) generation of solar thermal heat; c) use as a dynamic shading device. Cultivating microalgae in flat panel photobioreactors requires no additional land-use and is largely independent from weather conditions, allowing installations in urban environments. The carbon required to feed the algae is taken from a combustion process in proximity of the façade installation to implement a short carbon cycle, preventing carbon emissions to contribute to climate change. Microalgae also contain high-quality proteins, vitamins and amino acids that make it a valuable resource for the food and pharmaceutical industry. This network of diverse reconstruction activities constitutes an effective method for rebuilding the region, and also suggests new ways for architects to engage with society, sometimes as collaborators, sometimes as advisors, and sometimes as rebels.

Category 1 – Applied Innovations

This category was introduced for the first time this year to help drive forward future developments. It includes innovative projects for application in, or around, buildings and urban infrastructure with approaches ranging from saving energy, using new materials or recycling, closed material and resource cycles to intelligent controls and software applications.

SOLARLEAF

by Arup Deutschland GmbH

![]()

Jan Wurm from Arup Deutschland and Lukas Verlage, CEO Colt International, winners of the Applied Innovations category‚ explain their ground-breaking Solarleaf photosynthesising façade.

Jury statement:

“In the future we need to develop

buildings which don’t just offer

shelter and minimise energy

consumption but also try to deliver

answers to how we provide the

urban environment with energy,

water and better air quality ...

for the first time we have an

application that actually works

in an existing building.” -

Category 2 – Buildings

The Buildings category was open to built projects completed between 2011 and 2013 which met the highest aesthetic standards and featured innovative solutions that led to the more efficient use of resources, enhanced environmental protection and the creation of better living conditions.

The Port Sudan Paediatric Centre is located in a large desert between two hut settlements. It is a very poor area with a large concentration of refugees. This clinic is one of the few health outposts providing free health care to children of this large region. The building was designed for Emergency, an Italian NGO who provides free medical and surgical treatment to the civilian victims of war, landmines and poverty.

Because of the extreme conditions involved, simplicity was a strategy priority for this project, but without losing sight of quality medical and architectural standards for the project.

The one-storey building has three outpatient clinics, a 14-bed ward, a dispensary, spaces for diagnostic exams and service areas. The building adopted the adaptive principles of many Arab houses: minimising sun-exposed sides and opting for a hollow space conformation. As the Sudanese climate is extreme (50 degrees Celcius and sandstorms) a natural air treatment inspired by Iranian traditional systems called a badgir was adopted and integrated into a system of mechanical cooling. The resulting reduction in electricity consumption for air conditioning is estimated at about 70 per cent.

The need to purify wastewater from the clinics presented an opportunity to build public gardens - the only public spaces in the area: treatment for the water, and for the souls of patients and staff alike.

Port Sudan Paediatric Centre

by Studio Tamassociati, Italy

![]()

Raul Pantaleo from Studio Tamassociati, winners of the Buildings category, talks about the special design challenges involved in building a clinic in a remote, war-torn region of Sudan with limited resources, and at the same time producing a thing of beauty with public spaces for the community.

Jury statement: “This project makes a

valuable contribution to the medical

and social care of the local people

and its holistic design process

is very much in the spirit of

the Zumtobel Group Award.

The outcome is an ambitious design

that is focused primarily on its

practical purpose, without neglecting

architectural, sustainability and aesthetic

considerations.” -

Category 3 – Urban Developments & Initiatives

The focus in this category is on projects in an urban context: city development/planning strategies, masterplans, public space projects and ongoing research projects and social initiatives designed to enhance urban and social settings.

When an 8.8 Richter scale magnitude earthquake hit Chile in 2010, almost 500 people died in the following tsunami. After this catastrophe Elemental was given 100 days to come up with a strategy to rebuild the city of Constitución, located 400 kilometres south of Santiago, which was almost completely destroyed. The design process was participatory: asking residents to precisely define their needs and focus on establishing priorities. It was important to the designers that the community felt empowered enough to exert pressure on the authorities during implementation. One critical question was how to best protect the city against future tsunamis. The strategy was to dissipate, rather than resist the energy of nature: a geographical answer to a geographical threat. Elemental proposed planting a forest to protect the city from future tsunamis. When the waves first hit Constitución, they were 12 metres tall; a forested island to the north of the city dissipated their energy and, by the time they reached the city centre, they were only 6 meters tall. The idea was therefore to protect the city by redeveloping the riverfront with trees. This alternative was the most challenging, politically and socially, because it required the city to expropriate private land.

PRES Constitución

by Elemental, Chile

![]()

Alejandro Aravena from Elemental, Iván Chamorro from Arauco Forestry and Eugenio Tironi from Tironi Asociados, winners of the Urban Developments and Initiatives category, explain how they implemented the power of participatory design to rethink a Chilean town after a major earthquake in only 100 days.

Jury statement: “By adopting a

bottom-up approach, in a very

constructive way a joint decision

has been reached regarding what

the city should look like in the future.

This exemplary concept is not

restricted to Constitución, but could

also apply in many geographies

around the world that have been

destroyed by natural disasters.” -

License to Think

Interview with

Eugenie deLariviere

By Elvia Wilk

What do students want? During her final year of her masters programme at the Design Academy in Eindhoven, Eugenie deLariviere was faced with an institutional upheaval that prompted her to reconsider her entire education.

Eugenie deLariviere’s masters thesis project, titled “My Education Frustration”. (All images courtesy Eugenie deLariviere)

-

Your 2013 thesis project for your masters in Contextual Design at the Design Academy in Eindhoven was called "My Education Frustration". What was the situation at the school that prompted you to focus on education?

The Design Academy had been trying to reinvent its own system for several years. Nobody could agree on how to do this, which led to the resignation in June 2012 of the heads of three masters programmes. Part of the problem was the very hierarchical form of organisation that was developing – partially due to decisions the school was making, but also dictated by the Bologna Process, a system of standardisation that’s pushing a lot of schools throughout Europe in the same direction. Decisions about education are being made at governmental level; we have to decide how to adapt without losing our own perspective.

![]()

“This is (not) a manifesto” is a visual project by deLariviere expressing the opinions that arose on all sides following “Dutch Resign Week,” the week in July 2012 when three heads of the masters program at the Design Academy Eindhoven resigned.

-

»We need to be able to trespass out of our own disciplines.«

The student perspective gets lost because of institutional hierarchy, but is it also because students don’t feel accountable to the longevity of an institution they’re only a part of for a few years?

Yes, this was part of my struggle in getting students involved. It’s true that they don’t feel very concerned – but also, until then, they’d just never been asked what they thought. Change is about rethinking the structures that include or exclude them from decisions about their own education. In general we need a system change.

What are the main things that need to be overhauled?

One of the main things is the diploma, this idea that some knowledge can be accredited and some cannot. How do you differentiate? Today, when you’re looking for a job, it’s more about how personalities work together. We have to think in formations. Is the name of the school on the diploma important? For designers and architects it may be less complicated, because we can show our portfolios, but for education overall the diploma is really outdated.

But aren’t architects and designers the ones who need the most rigorous accreditation process, because they’re liable for designing buildings and objects requiring real technical, safety, and environmental parameters?

Yes, definitely, we can’t lose the technical part. But there’s a whole other side to architecture and design. Both are moving out of their fields – they’re not so much about buildings or objects anymore, but something much bigger. How can you accredit that type of knowledge?

Soft skills are much harder to transmit and measure than hard skills. What did you learn about teaching and learning them during your research?

That you learn the most from your peers: whether it’s one class having an idea together, or a whole generation sharing values, we learn from each other. It’s not a new idea, but it made me realise that sharing soft skills with each other depends on having a shared space. You need spaces to form groups of people, and groups of people to make education happen.

-

![]()

![]()

Is it possible for an established institution to adapt by creating new models, or is it necessary to go beyond or outside the institution to really create something new?

What I found is that new schools and temporary programmes die if they don’t get institutionalised. If they’re not accredited people don’t trust them – even if it’s a great idea and everyone is enthusiastic. Some programmes, such as Department 21 at the Royal College of Art in London, started well, but because they weren’t incorporated into their own institutions, died out. Yet The School of Walls and Space at the Royal Academy of Visual Arts in Copenhagen was also self-initiated, but in the end the academy assigned a budget and it became a proper department. The academy was smart, realised that something was happening within itself and gave it a chance.

After sending a letter to Eindhoven’s creative director outlining her concerns‚ deLariviere held open discussions with students and faculty‚ and staged student interviews.

-

What about at Eindhoven? How receptive was the faculty to your initiative, and were there long-term outcomes?

I sent a letter to the school creative director, Thomas Widdershoven, explaining my complaints. Then we had a meeting and together organised a debate. All the mentors from the school were invited, but the students were the ones speaking. We also invited Timo de Rijk, who had published a very critical article on the academy. That evening led to other evenings where students were invited to speak about their projects, and so the perspective started to change a bit.

Is this resistance to including student voices because it seems like too much work to involve them?

Administrations think it will be more work, but they also think it’s not worth it, that students don’t have interesting things to say.

»Change is about re-thinking the structures that include or exclude students from decisions about their own education.«

The hierarchy is clear – it’s like if you don’t have your diploma yet, you’re not able to think. At the end of the first debate we organised, the creative director of the school came up to me and said, “I didn’t know students had so much to say! They’re actually smart!” I thought, come on, you just became the head of one of the greatest design schools in Europe, and you don’t believe in the intelligence of your students?!

Is design education unique or should everything be interdisciplinary?

We need to be able to trespass out of our own disciplines. But we also need to be experts in our own area. It’s not that we have to be designers plus something else; it’s that we need to collaborate and make connections. Students very often have the drive to look into another subject, but don’t have access to the relevant knowledge within their institutions.

-

Eugenie deLariviere is a young designer interested in how students can be the motor of active changes within their education. In her research she looks at how can educational systems be rethought from within, focusing on putting forward the vision and interests of the ‘new generation’. She has moderated, co-organised and participated in various symposiums on the future of design, and is now a mentor at the Rietveld Academy.

eugeniedelariviere.com

What were you expecting from your education when you began?

I was expecting to become a designer making objects, and then midway through I realised what I was going to do with my life wasn’t what I was being taught. I really started questioning what I wanted out of it: to rethink what design could be. I was concerned that schools weren’t changing with the definition of the profession in the outside world. During my masters, several students were older than me, had experience and were ready to take on work that was important to them. I was still in this student-school relationship I’d been in since I was three! In my last year of study I realised I didn’t care about getting the diploma anymore.

![]()

Believing education is about shared space, her thesis project focused on forging and documenting spaces for interaction. (Photo: Lonneke van der Palen © Design Academy Eindhoven)

-

Education as Curation

AA Night School, LondonWhat goes around comes around. The AA Night School, founded in 2013, offers events such as book readings and discussions, cross-practice crits, architectural photography, workshops and talks. It takes its inspiration from the origins of the AA (Architectural Association) itself, which started as an evening school in the 1870s. Back then the programme was a radical mix of peer-directed learning and critique organised by young practitioners reacting against the system of office tutelage – effectively cheap labour (think unpaid internships today).

Billing itself as “an ongoing speculative project dealing with alternative models of architectural education”, the Night School does not claim to offer an alternative model itself but aims to become a test pit and mirror for new ways to learn and engage with architecture. Time will tell whether it progresses beyond a curated events progamme to offer a true counterpoint to the AA’s system. p (rgw)

(Photo: Valerie Bennett/Architectural Association Photo Library)

-

![]()

Education as Branding

Strelka Institute, MoscowFounded in 2009 in a former chocolate factory on an island near Moscow, the Strelka Institute offers a free annual nine-month postgraduate research-based programme in urban design and development for 45 international students. It also hosts free summer-long public programmes of lectures, workshops, discussions, concerts, and film screenings, has a digital publishing arm, and a great bar overlooking the Moskva river.

With a staff of both established names and young, hip contributors and a tightly controlled graphic identity, Strelka garners acres of press attention. There’s also a touch of glamour and mystique, due to the billionaire backer who supports the programme. But it is also proving increasingly influential beyond the scope of teaching, with events like the annual Moscow Urban Forum and a consultancy for public design competitions. Whilst everyone is critiquing or abandoning the institute model, perhaps the most radical move really is to found a new one – providing you can find the cash. p (rgw)

Overlooking the Moscva river‚ across from the iconic Cathedral of Chrsit the Savour in Moscow‚ Stelka is situated on an island in a former chocolate factory. (Photo courtesy Strelka Institute)

-

Deschooling

![]()

SocietyLearning in the networked era

By Ethel Baraona Pohl

-

![]()

![]() re open source models the best way to democratise education? To learn more, we need to “unlearn” says architect, writer and publisher Ethel Baraona Pohl.

re open source models the best way to democratise education? To learn more, we need to “unlearn” says architect, writer and publisher Ethel Baraona Pohl.In the past decade the architect’s role, and consequently the way knowledge about architecture is shared, has undergone a radical shift. Several pedagogical experiments that have emerged in the past years can be understood as a clear response to the generalised – and problematic – economic, social and political situation. Economic growth from the 1980s until 2008 transformed academia itself into a commodity system, in which not only education but also our social and cultural reality became “schooled”. Yet before this period, in 1971 the philosopher, social critic and priest Ivan Illich published a book called Deschooling Society, in which he referred to the revolutionary potential of deschooling and outlined the possible use of technology to create institutions serving personal, creative, and autonomous interaction. Illich’s concept of deschooling is clearly relevant today, given the contemporary relationship between digital tools and learning, free access to information, and new economic models.

Questioning the importance of an accredited academic curriculum is the leitmotif of contemporary initiatives such as The Public School, which began in 2007 and defines itself as: “a school with no curriculum” that is not accredited and does not give out degrees. Anyone with interest can join the courses without enrolling or paying, and anyone can propose subjects that they wish to study. Similarly, the Free University NYC was conceived as a type of educational strike one day before May Day 2012, International Workers’ Day, with several days of free and open-source classes in parks and public spaces in New York City. Another model, the recently inaugurated [in 2012] Free University in Milan, offers biannual study cycles, based on face-to-face meetings with a multidisciplinary approach and with a mission to break down the hierarchies of traditional academia. But it is not just the concept of accreditation that is under reconsideration. -

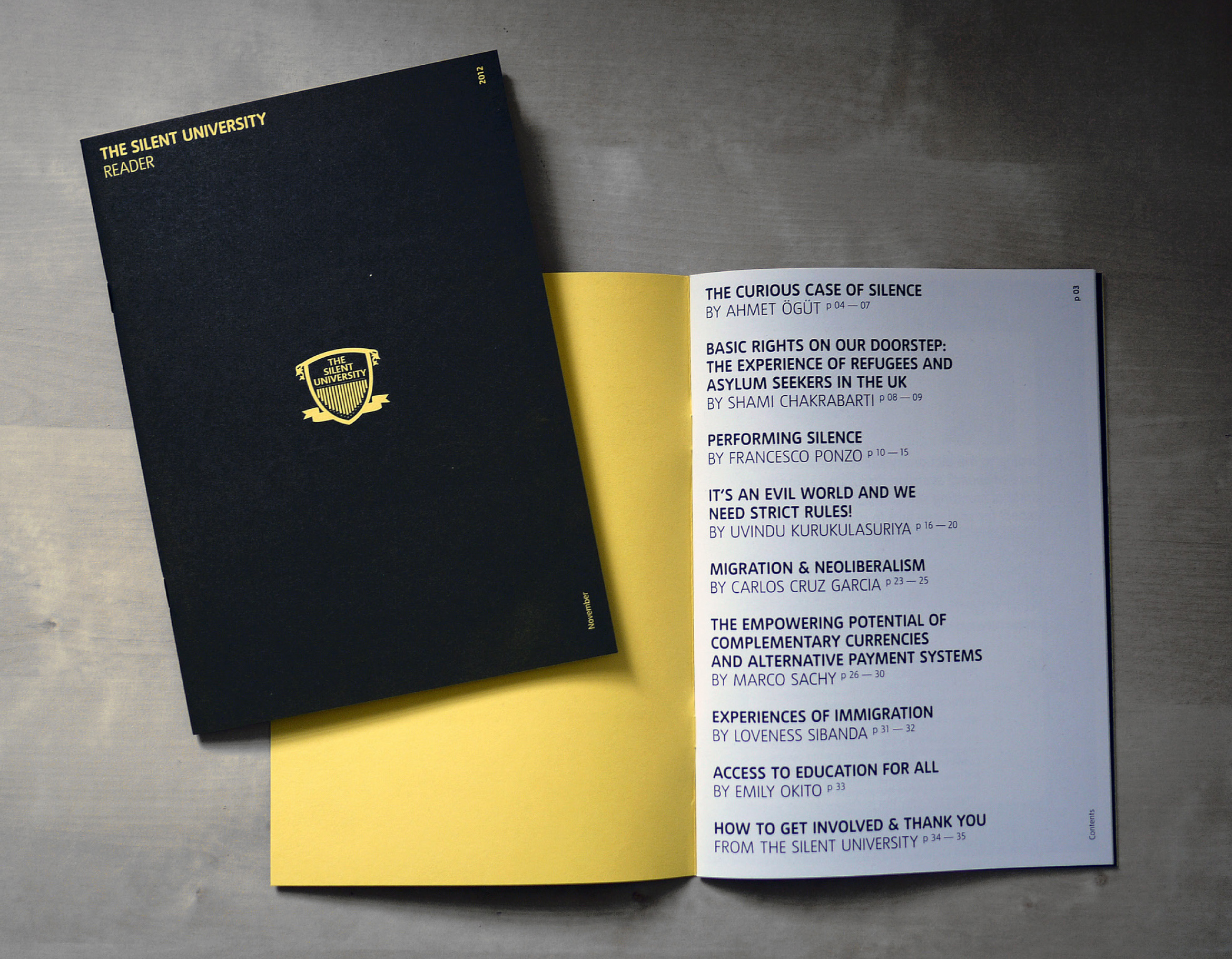

The crossover of architectural education with fields like politics and economics is the basis of the Forensik Mimarlik, founded in 2014, which is focused on critical spatial practices, methodologies and architecture in the geography of areas of Turkey.

The participants work in the context of borders, politics and law, developing a research practice that deals with sites of conflict. In the same way, The Silent University, an autonomous platform by and for refugees, asylum seekers and migrants, was created in 2012 with the aim to address and reactivate the knowledge exchange of the participants. In particular sharing the experience of people who had a professional life and academic training in their home countries, but, now in the UK, are unable to use their skills or professional training due to their legal statuses.Free University installation at the Triennale di Milano‚ 2013. (Photo: Triennale di Milano)

-

»Economic growth has transformed academia itself into a commodity system. We must un-learn the traditional models that are based on unequal exchange.«

![]()

![]()

Silent University class in progress; the University reader. (Photos courtesy The Silent University)

-

![]()

Visual medium used by the Public School Los Angeles. (Photo: Julie Faith)

-

Ethel Baraona Pohl is an architect and writer, who with César Reyes Nájera founded dpr-barcelona, an innovative research studio and publishing company based in Barcelona, dealing with three main lines: publishing, criticism and curating.

dpr-barcelona.comProject links:

thepublicschool.org

freeuniversitynyc.org

ira-c.org

twitter.com/ForensikMimarlk

thesilentuniversity.org

MOOC

Far from site-specific academic practices, numerous non-site-specific initiatives have sprung up, from open-air classes to on-line courses. Practices of giving talks or teaching whole courses remotely and in real-time began a few years ago with wikis, blogs and podcasts, and have now evolved on a broad scale. One of the best-known formats currently in use is the MOOC (Massive Online Open Course), in which professors offer courses or talks for an unlimited number online students to follow. #webinar[s], now found on Twitter, are invitations to a “web seminar” open for anyone interested in whatever topic is at hand.

Are these open-source models the best way to democratise education? As with any paradigm shift, people take extreme positions on all sides, providing profound critiques of the emerging ways to share knowledge. Despite the success of some courses, the MOOC model, for instance, has been severely criticised; its detractors refer to the difficulty of maintaining academic standards. Yet this criticism can be flipped in favour of the “emancipating teacher” a term used by the philosopher Jacques Rancière in his book The Ignorant Schoolmaster (1981). Rancière wrote that every person is of equal intelligence, and that the insights from which knowledge is constructed can be found in any collective educational exercise. It would not make sense, according to this logic, to discredit the whole concept of the MOOC; evaluation of a class should be based on content. If a class is badly taught, it will be worthless even if taught within the walls of some hallowed university. And regrettably, this happens with certain regularity even in classrooms.

The most interesting developments in education may have yet to take place. All these new, intangible educational infrastructures that form part of our daily life implicitly have an enormous learning potential, but firstly we must un-learn. We must un-learn the traditional models that are based on unequal exchange. We must un-learn the academic model created more than a century ago, which aimed to produce “workers” according to the canons of the Industrial Revolution and which so far have only evolved in step with the model of capitalism. p -

Education as Open Platform

The Public School for Architecture, BrusselsThe idea behind the original “Public School” (PSFA), initiated in Los Angeles in 2007, was to create an open online platform for autodidacts around the world to self-organise and exchange knowledge without college fees and without accredited teachers. The idea has blossomed and now groups of people organise in numerous cities around the world to do just that. Two of these have so far been geared specifically towards architecture.

In 2009, Common Room and Telic Arts Exchange started a Public School for Architecture in New York City – this has since dropped “architecture” from its name and expanded beyond the discipline. But this year in Brussels, Common Room, Telic Arts Exchange, and Recyclart came together to launch a new PSFA, with the goal of “creating a public for architecture while opening up architecture for the public”. Rather than a pre-established curriculum, the PSFA-BXL allows users to propose classes, and when enough interest is shown the class becomes open for scheduling – “forming communities independent of institutional interests”, a space where “architecture can become political again”, according to initiator Lars Fischer from Common Room. Most classes are discussion-based, but many include workshops. It’s still architecture – just expanded, or maybe exploded. p (ew)![]()

-

Eugene Asse was born in 1946 in Moscow, Russia and is a graduate of the Moscow Institute of Architecture (MARHI). In 1970 he worked as an architect in Moscow's Municipal Planning Office before completing his postgraduate studies in 1981 where he then headed the Urban Design Research Group in the State Institute of Design until 1986. In 1994 he founded the independent research and design group “Architectural Laboratory” and he is also a member of the European Cultural Parliament. Twice Commissioner of the Russian Pavilion at the Biennale of Architecture in Venice, he writes and lectures extensively on urban design and theory of architecture.

![]()

Our guest reviewer for this issue’s bookmarked section is Eugene Asse, head of Asse Architects and founder and dean of the new Moscow Architecture School, MARCH which launched in 2012. MARCH aims “to build up a new model of architectural education in Russia that produces professionals trained to the highest international standards”, says Asse. It was founded as a postgraduate alternative to the two poles of architecture currently available in city: the Moscow Institute of Architecture and the Strelka Institute. MARCH is validated by the London Metropolitan University. uncube asked Professor Asse to pick what he considers four essential books for the architecture undergraduate.

![]()

-

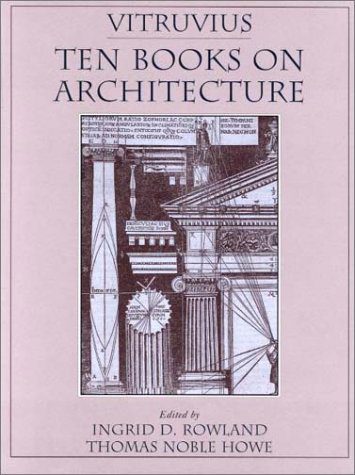

De Architectura, or Ten Books on Architecture as it was published in English, was written by the Roman author, architect and civil enginer Marcus Vitruvius Pollio during the first century BCE. Many copies existed in manuscript form during the Middle Ages (92 of which survive today) and interest in the work was revived again during the Renaissance. The first printed edition was published in 1486, and has lived on in various translations and edited versions throughout the centuries.

Ten Books on Architecture

Real author: Vitruvius

Editors: Ingrid D. Rowland, Thomas Noble Howe

Re-published: Paperback‚ March 2001

Cambridge University Press

ISBN: 9780521002929In Praise of Shadows

Jun'ichirō Tanizaki

Original Japanese publication 1933

First English translation 1977, Leete’s Island Books

73 pages

ISBN-13: 978-0918172020

leetesislandbooks.com

![]()

![]()

After two millennia, this is still the best book about our profession. Thanks to Vitruvius one can understand what it means to be an architect and what an incredible range of skills and knowledge is required. Vitruvius’ trinity for an ideal building – utilitas, firmitas venustas (commodity, firmness, delight) – is still valuable even today.

![]()

This book is not strictly about architecture. It speaks of light and darkness, of East and West, of permanence and change, of old and new. Nevertheless I consider it to be one of the most important architectural books, which tells the extraordinary and poetic story of space, materials, feelings and values in architecture.

-

Invisible Cities

Italo Calvino

Original Italian publication 1972

First English translation 1974, Harcourt Brace

165 pages

ISBN-13: 978-0156453806History of Architecture

Auguste Choisy

Original French publication 1899

![]()

![]()

This book is about power of imagination. In it Italo Calvino designed fifty-five absolutely amazing cities, each one with its own history and fantastic architecture, populated by strange people living an extraordinary life. For the architect, this book is a unique lesson of freedom, poetry, courage and wisdom.

![]()

Choisy was the only historian who analysed architecture from an anatomical point of view. He described buildings as living organisms, discovering their skeleton, muscles and skin. It is no accident that Le Corbusier, who was not wont to ready praise, called Choisy’s 1899 Histoire de l’Architecture “the most worthy book ever written on architecture”.

-

![]()

-

AUSTRALIA

Issue No. 27:

October 30th 2014Photo: Nils Koenning

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Intelligence starts with improvisation.«

Yona Friedman

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents

The school follows a type of construction normally used for parking garages. (Photo: Philippe Ruault)

The school follows a type of construction normally used for parking garages. (Photo: Philippe Ruault)