-

Magazine No. 32

Expotecture

-

No. 32 - Expotecture

-

page 02

Expotecture

-

page 03

Editorial

Expotecture

-

page 04 - 09

Fair Trade

Paul Greenhalgh introduces Expos: "the most effective peacable way to wage war"

-

page 11

Heart of Glass

The Crystal Palace, London, 1851

-

page 12

Beautiful Climbing Frame

The Eiffel Tower, Paris, 1889

-

page 13 - 22

Manufactured Consent

Jonas Staal on propaganda and commerce at the 1937 and 1939 World’s Fairs

-

page 23

Fascists to Fashionistas

Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana, Rome, 1942

-

page 24 - 31

The Future is Here

Philosopher Mark Kingwell remembers the 1967 Montreal Expo

-

page 32

Memories Worth Keeping

Time Capsule, Osaka, 1970

-

page 33 - 42

Progress and Harmony for Mankind

Crystal Bennes looks back at the optimism of Osaka Expo 70

-

page 43 - 49

Live Fast, Die Young

After the party at Hanover Expo 2000 by Rob Wilson

-

page 50

DIY Expo

The World is Not Fair, Berlin, 2012

-

page 51 - 59

Putting an End to the Vanity Fair

Exclusive interview with Jacques Herzog about the Expo 2015 masterplan

-

page 60 - 64

In the Photo Booth with...

Richard van der Laken

-

page 65

Klaustoon

XXII. The Future Was Yesterday

-

page 66

Next

Frei Otto

-

-

uncube's editors are Sophie Lovell (Art Director, Editor-in-Chief), Florian Heilmeyer, Rob Wilson, Elvia Wilk and Fiona Shipwright; editorial assistance: Sara Faezypour; graphic design: Lena Giovanazzi, graphic assistance Diana Portela.

uncube is based in Berlin and is published by BauNetz, Germany's most-read online portal covering architecture in a thoughtful way since 1996.

In the run up to the Expo 2015 in Milan, uncube takes stock of what’s so weird, wonderful and plain warped about World’s Fairs.

What began as a glorified industrial age trade fair has transitioned through national branding, motivational propaganda, one-upmanship and hymns to the future into a series of giant, multi-billion dollar temporary world spectacles that nobody quite remembers the reason for.

In this issue, we invite an illustrious set of expert authors to take us on a journey through some of the most interesting World’s Fair iterations – and the questions they throw up. We have an exclusive interview with Jacques Herzog who talks about masterplanning a World’s Fair in 2015. And we ask: will Milan set new sustainable standards or be just another giant global party with the environmental impact of a crude oil spill?Cover image: Visitors at the Perisphere, New York World’s Fair 1939. (Photo: The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations) This page: New York World’s Fair 1964: Sinclair Oil’s fibreglass Tyrannosauros Rex and admirers. (Photographer unknown)

-

FAIR TRADE

If you thought Expos were just celebrations of human achievement, think again

By Paul Greenhalgh

_

Number of participating countriesSources: Bureau International des Expositions: BIE/Wikipedia/Expo Milano 2015

-

![]()

Nationalism, brand identity, propaganda, politics and economics, all wrapped up in spectacle and shiny architectural gestures: Expos, says author and historian Paul Greenhalgh, are a quintessentially modern invention – the most effective peaceable way to wage war.

When the Shanghai Expo closed its doors for the last time on October 31 2010 it was the most heavily attended Expo of all time. 73 million visitors strolled and queued around the spectacular site on the banks of the Huangpu River in the heat and the rain, to see structures and buildings built by the Chinese and by 246 participating countries and international organisations. In all dimensions it outstripped everything that had gone before and appeared to signal the complete revival of the Expo medium.

So as we watch the final preparations for the Milan Expo 2015, the next fully official universal exposition after Shanghai, the question presents itself as to what, in the twenty-first century, these enormous undertakings are actually for? What are they actually about? First of all, and without being too cynical, we can say that over the last 150 years the success or failure of Expos has never really been to do with culture, education, social improvement, the arts, urban planning, or international understanding, to cite some of the themes they have purportedly been about.

These were invariably the grand rhetorical messages trumpeting out from the sites, and obviously significant displays onsite dealt with these themes: in the golden age of Expo however, the driving forces were not these but something else: politics and economics. Expos are a quintessentially modern invention, the physical manifestation of material progress, and their rationale can be found in the need for money and national cohesion. -

![]()

That is why governments and the private sector have invested in them, and why they were often created on gargantuan scales. They were the most effective peaceable way to wage war.

World’s Fairs haven’t enjoyed an even history since the founding event, The Great Exhibition of the Works and Industries of All Nations held in London in 1851. There were two periods in which the medium took on a frequency and a drama that effectively made them into golden ages: the fin de siècle, and the 1960s.

During the first, beginning with the Philadelphia Exposition of 1876, there was an epic-scale Expo somewhere in the world every few years through to the First World War. In some years, such as 1888 (Glasgow, Barcelona, Melbourne), or 1906 (Toronto, Marseilles, Bucharest, Christchurch) there was more than one. Every one of these was spectacularly ambitious and, judged by their own criteria, highly successful. Each one would have made the Millennium Dome, the last feeble and ill-fated attempt at the medium in England in 2000, look like a village fête.

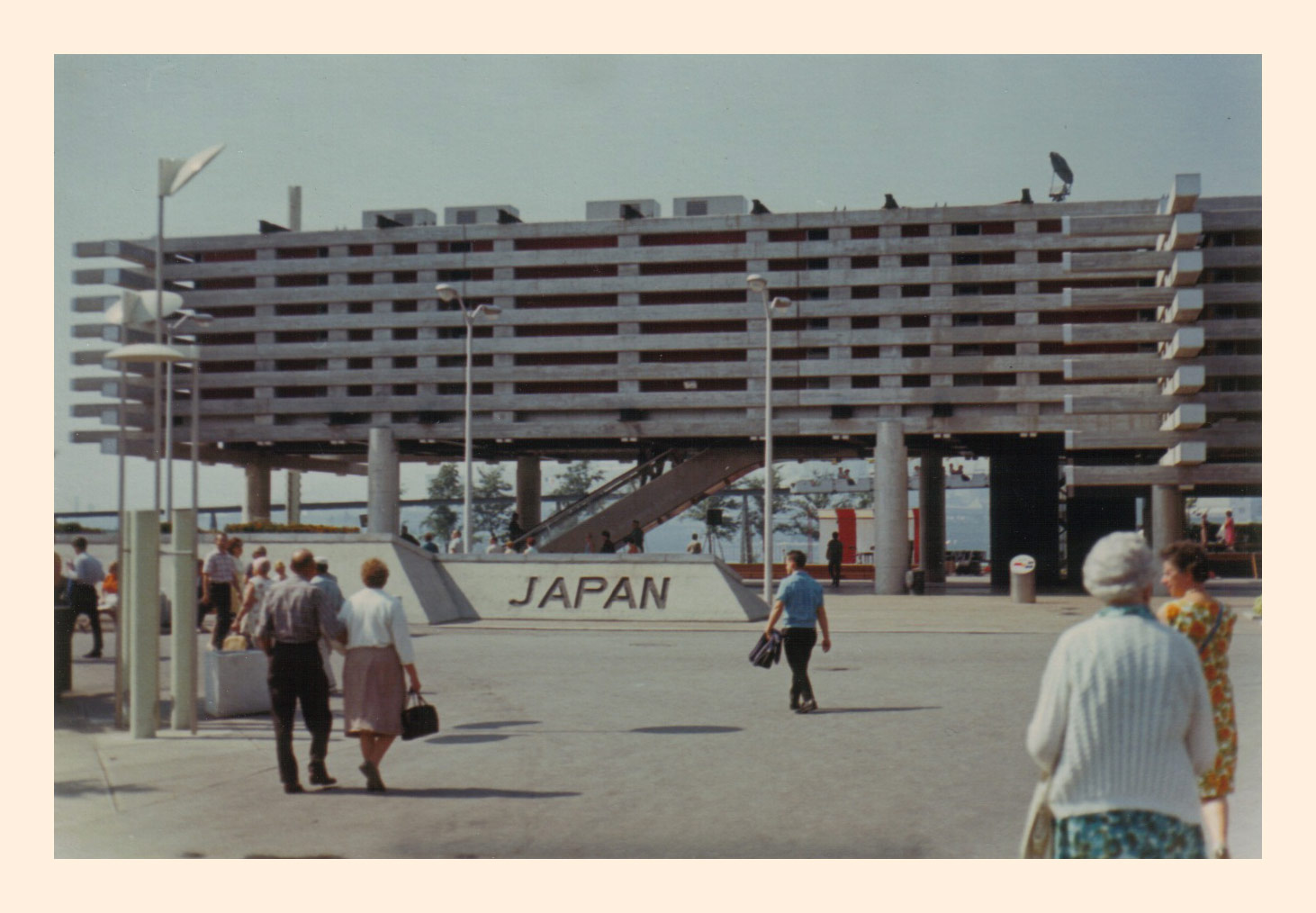

Major cities, such as Paris, Chicago, Philadelphia, Barcelona, Brussels, San Francisco, Buffalo, Turin and St Louis were transformed by them, and as this list shows, at that point Expo was basically a creature of Europe and North America. The second golden age, boasting far fewer but truly spectacular events, was the 1960s. The sequence then was Brussels (1958), Seattle (1962), New York (1964), Montreal (1967), and Osaka (1970). The five shared a stylistic, artistic, technological, and intellectual consistency that helped shape and define that brilliant short run of years. One of the more remarkable statistics is that at 51 million visitors, more than double the population of Canada attended the Montreal Expo.

These two golden ages, contained Expos that in so many ways shaped, influenced and reflected the culture and ethos of the societies they decorated.

-

_

Total costs

(In USD millions)

»Pessimism doesn’t make Expos: the model is Star Trek, not Blade Runner.«

Sources: Bureau International des Expositions: BIE/Wikipedia

-

_

Number of visitors

(in millions)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Expo visitor statistics. (source: Bureau International des Expositions: BIE/Wikipedia)

-

Paul Greenhalgh is a writer, historian, university and museum professional in the fine and decorative arts. He is currently Director of the Sainsbury Centre for the Visual Arts, one of the UK’s principal research institutions for the study and display of all forms of visual art. Prior to this, he held a number of senior posts around the world, including Head of Research at the V&A Museum in London, President and Director of the Corcoran Gallery of Art and College of Art and Design in Washington DC, President of NSCAD University in Canada, teacher at the Royal College of Art and Cardiff College of Art and Design. He has organised various large-scale exhibitions in a number of countries, including the UK, USA, France, Spain, Japan, and Canada, most notably Art Nouveau 1890-1914 (2000-2001, London, Washington, Tokyo). He has lectured all over the world and has published a number books and articles across his specialist areas, which include fin de siècle art and design, Modernism and Modernity, Art Nouveau, Symbolism, Cubism and Abstract art; the History of Ceramics; and the contemporary crafts. His books include The Modern Ideal: The Rise and Collapse of Idealism in the Visual Arts from the Enlightenment to Postmodernism, The Persistence of Craft: The Applied Arts Now, and Art Nouveau 1890-1914 and Fair World: A History of World’s Fairs and Expositions.

![]()

The Paris Expositions Universelles of 1889 and 1900 branded the city forever, and brought every great artist, designer, musician, novelist, scientist, and businessman in Europe into the French capital; the Chicago Columbian of 1893 created the city and St. Louis was a different place after 1904.

And later, the sixties Expos provided a vision of optimistic flamboyance that provided a template for urban life across the planet. The Seattle Fair marked the arrival of the West Coast as the capital of hi-tech; Montreal defined modern Canada; and the Osaka Expo, the first in East Asia, signalled the arrival of the new Japan as a world power.

After 1970, as glib irony increasingly defined urban existence, and the postmodern world defined itself through texts that no one had read, the Expo slid into decline. Pessimism doesn’t make Expos: the model is Star Trek, not Blade Runner. There were still large-scale events, but collectively they were less visions of the future, and more educationally inflected, consumer-driven funfairs.

But now it appears Expo is back. Shanghai was a seriously important event for China. The city recovered hectares of decayed land; the Chinese population flooded to the city; the possibility of transformation flashed across the minds of millions. Once again, it seems, Expo was concerned with its historic themes: politics and economics. Interestingly, for over twenty years the American government had determined not to take part officially in Expos: but when they looked at the prospectus for Shanghai, at the eleventh hour they scrabbled together a pavilion with a speed that bordered on panic. Politics and economics do that to governments. So, how will Milan be received? Can the Expo 2015 lift the fortunes of the city and the country? Will our vision of Italy shift? Will trade increase? Will immigration peak? Will companies flood into Lombardy? Will Europe once again be pulled south? Is there another Renaissance afoot? We will know the answers to these questions soon enough. I

-

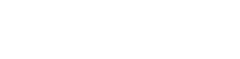

First among equals in the history of Expo structures, the Crystal Palace was built in London’s Hyde Park to house the Great Exhibition in 1851 and display the very latest technology. The glass and steel building was a gigantic technological feat in itself, housing more than 14,000 exhibitors in 9,200 square metres of exhibition space. It was perhaps the greatest feat of architectural Empire-branding ever undertaken in the UK. The design was by Joseph Paxton, who was, appropriately enough, a gardener by trade. Three years later, the building was moved to a new home on a hill in Sydenham in south-east London and extended in size. Here it shared a park alongside a set of newly-installed dinosaur models and landscaped water features.

It is however perhaps its end, rather than its inception, which has lent the building its mythical status – on the evening of November 30, 1936 the Crystal Palace was consumed by a fire which destroyed this symbol of Victorian technological might in a matter of hours. Thousands of Londoners came to watch as the spectacle became a spectacle, amongst them Winston Churchill who is said to have remarked: “this is the end of an age”. But perhaps he spoke too soon – in 2013 it emerged that a Chinese developer was in talks with the local authority and London’s Mayor, Boris Johnson, about a proposal to rebuild the palace. Third time lucky? p (fs)

![]()

Photo: Public domain/originally published in The Sphere, 1936.

-

“Imagine for a moment a giddy, ridiculous tower dominating Paris like a gigantic black smokestack”. To the modern eye, it’s almost inconceivable to imagine the city without that most famous of tours. But this icon of the French capital, indeed of the country itself, was not met with universal acclaim upon the unveiling of its design in the late nineteenth century.

During its construction a group of 300 writers, painters, sculptors and architects launched a campaign to “protect” the beauty of Paris from Gustave Eiffel’s 324 metre-tall feat of iron lattice engineering. The “Artists’ Protest” which raised the “smokestack” objection would ultimately fail and the rest is of course history, albeit one that has seen the tower facilitate the discovery of cosmic rays, survive two world wars and earn its designer a considerable fortune from the entrance fees before it became state property.

Arguably the most recognisable expo structure in the world, with a legacy that contemporary fair organisers can only dream of, the Eiffel Tower was the jewel in the crown of the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1889 through which visitors would enter the fair. In 2010 this “beautiful climbing frame for energetic tourists” (Paul Greenhalgh) welcomed its 250 millionth visitor – not bad for a temporary structure, originally scheduled for demolition in 1909. I (fs)

![]()

-

![]()

![]()

Paris Exposition Universelle 1937 and 1939 New York World’s Fair

By Jonas Staal

-

Artist Jonas Staal, whose work deals with the relationship between art, politics and ideology, examines the role of propaganda during two World’s Fairs from the 1930s – a shifting time of extremes of capitalism, nationalism and “democratism” in a world on the brink of war.

Democratism

The world fair model, established in 1851 with the building of the famous Crystal Palace in London’s Hyde Park, embodied the ideal of peaceful, international coexistence among nation states. Each of the national buildings functioned as a cultural embassy, comparable to “gigantic potlatches, joyous ritual displays of richness and power”, in the words of anthropologist and philosopher Raymond Corbey. These peaceful, sanitised, didactic displays sought to prove that the participating nations were capable of engineering civilisation through colonialisation and industrialisation. Western nations established their “democratic” capacity by acknowledging a variety of different cultures in their displays — and then demonstrating that they could manage these cultures.

The world fair modelled the principle of capitalist democracy before it became an established form of governance. The term “capitalist democracy” emphasises democracy not as a neutral framework capable of embracing a variety of different ideologies, but as an ideology in and of itself. “Democratism” is this ideology.

The world fair model highlights three crucial characteristics of democratism: (1) the desire to engineer peaceful coexistence among different cultures and ideologies; (2) a prohibition against questioning the engineering structure – colonial capitalism – upon which this peaceful coexistence is based; and (3) the close collaboration between government and private enterprise.Previous page: Sailors pose in front of the Eiffel Tower, Paris Exposition Universelle 1937. (Photo: gallica.bnf.fr/Bibliothèque nationale de France)

-

![]()

Totalitarianism

(Paris 1937)

While democratism is ubiquitous today, the Paris World’s Fair of May 1937 posed a considerable challenge to the sustainability of this form of governance. With Europe on the brink of another world war, the central intention of the 1937 world fair was, according to art historian Dawn Ades, to “shore up Europe’s faith in civilisation… Only in a world fair on this scale would it have been possible for the Spanish Republicans and Nationalists to be present simultaneously.” While we remember the Republican pavilion, since it was the first place where Picasso’s Guernica was publicly displayed, how did Franco’s nationalist military insurgency against a democratically elected government gain a place alongside established nations?Looking from the “House of Italy” towards the illuminated facades of the pavilions representing the USSR (centre) and Nazi Germany. (Photo: gallica.bnf.fr/Bibliothèque nationale de France)

-

The answer: the Vatican. It was thanks to “the Nationalists’ fusion of politics and religion … that the Vatican provided Franco’s side with an opportunity to participate”, inside its own pavilion. What makes this intervention so relevant is not simply the perverse bond between the religious institution of the Vatican and military fascist regimes, but the fact that it lays bare the very origin of the concept of propaganda: its inception can be traced to 1622, when Pope Gregory XV named an anti-Protestant missionary organisation set up by the Vatican the Congregatio de Propaganda Fide, or Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith.

Franco’s creation of a pavilion within the Vatican’s pavilion – even before the city-state itself existed – reveals what is at stake in the so-called peaceful coexistence of nation states at the World’s Fair: a battle for acknowledgement by the key players of democratism. What Franco understood was that, in the context of a world fair, an excessive display of power would undermine his cause. Rather, he simply had to become one among many respected states. His cause was aided by two nations that did not share his concern for subtly and restraint at the fair.

If the decision to place the German and Soviet pavilions in the centrally located International Exhibition was an attempt to enforce the idea of European unity, the effort failed. The Soviet pavilion, designed by architect Boris Iofan, functioned mainly as a pedestal for Vera Mukhina’s enormous sculpture Worker and Collective Farm Woman, depicting two gigantic figures striding forward while holding a hammer (male) and a sickle (female). If these figures were striving toward anything, it was toward the German pavilion, which was directly in front of the Soviet pavilion, across a road.

The role of art as propaganda in capitalist democracy is such a taboo subject precisely because the monumental structures of the 1937 German and Soviet pavilions so violently portrayed what we would come to understand as propaganda. However, it was in their shadow that Franco was able to provide his fascist rule with a sense of cultural respectability. This dynamic reveals how liberal democracy has been historically dependent on “totalitarianism”. .

Our conception of propagandistic art has been restricted to so-called totalitarian regimes, including Fascist Italy and Maoist China. -

Only when hysterical musicals and posters slip through the North Korean border is the word “propaganda” used in a more or less serious manner, yet always with the full conviction that only the most brainwashed of people could be susceptible to the manipulative force of this kind of imagery. This is what I refer to as “propaganda’s propaganda”: the absolute conviction of inhabitants of democracies that their world is lucid, whereas the poor, underdeveloped subjects of Kim Jong-un still naively gather in celebration around images of happy factory workers and peasants. Apart from this being a grave misunderstanding of those subjected to this type of imagery, it is exactly this logic that structures democratist propaganda par excellence: the belief that we are somehow “beyond” propaganda. The idea that there is a clear and absolute historical distinction between totalitarianism and democracy is the core of propaganda’s propaganda.

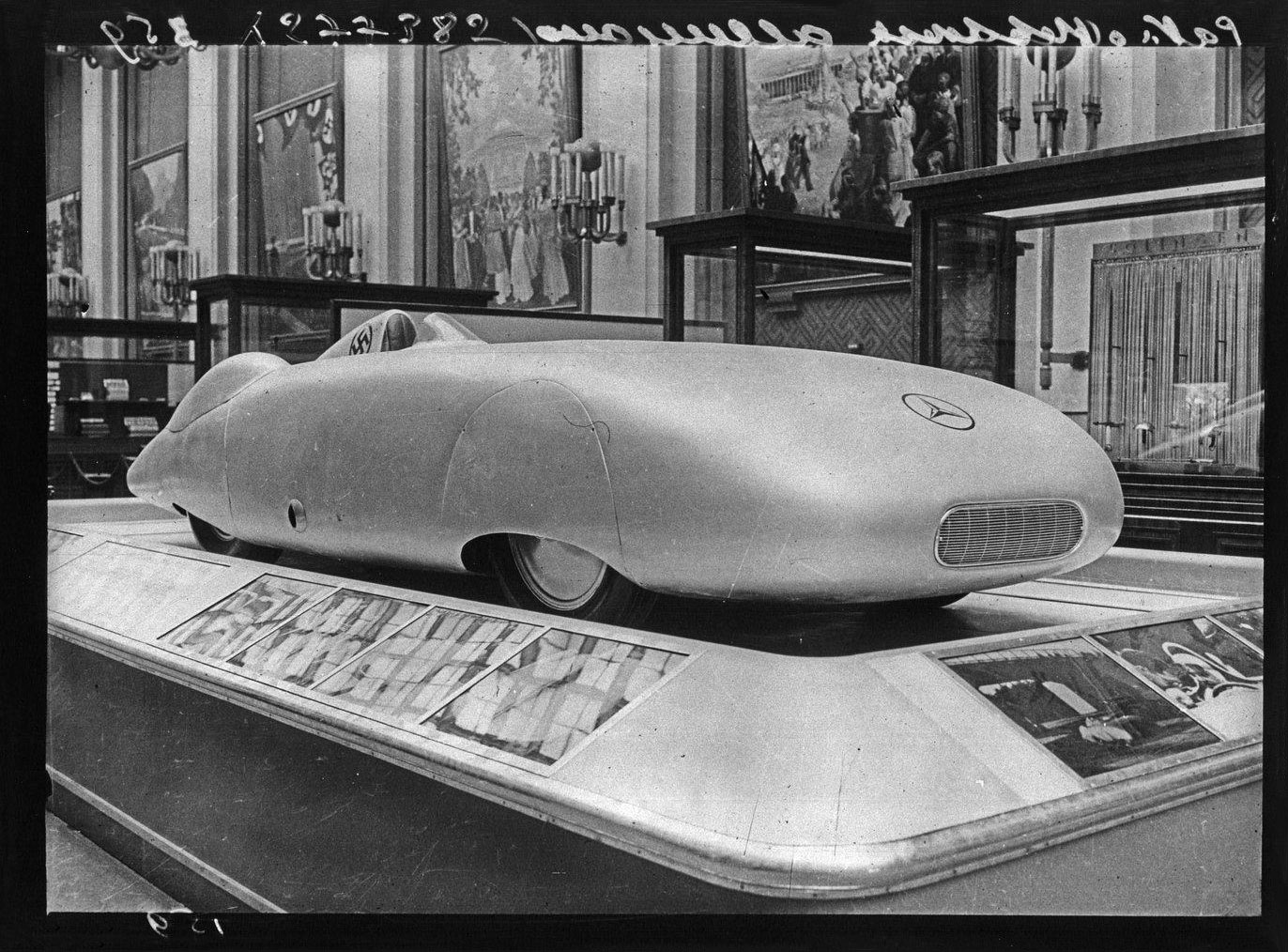

The interior of the German pavilion, replete with lavish treasures; among them a Nazi-branded Mercedes. (Photos: gallica.bnf.fr/Bibliothèque nationale de France)

![]()

![]()

-

Propaganda

Contrary to what many believe, propaganda was not invented by the Nazis or the Soviets. In fact, Hitler and his propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels based the Third Reich’s propaganda apparatus on Hitler’s own experience in the army during the First World War. Hitler was convinced that the defeat of Germany had been the result of the refined propaganda tactics of the British War Propaganda Bureau, which operated from 1914 to 1917.The “Court of Peace” area at the 1939 New York World’s Fair. (This image and all that follow: New York World’s Fair 1939-1940 records, Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations)

-

This bureau, generally referred to as “Wellington House”, in no way fits the prevailing image we have of propaganda. It did not make agitprop posters, it did not commission gigantic bronze statues and it did not primarily target the masses. Instead, Wellington House developed an intricate network focused on gathering and distributing knowledge to elites in the societies that the British needed on their side. Its main tactic was to never have its actions be recognised as propaganda. It achieved this by giving all the information it distributed an air of academic precision and impartiality. Modern propaganda was thus born in Britain, a supposed paragon of democracy. The aim of this propaganda was to sustain the belief among British citizens that information circulated freely and that public opinion was formed without coercion.

Only two years after the foundation of Wellington House, Edward Bernays, the nephew of Sigmund Freud, was employed by the American president Woodrow Wilson in his own Wellington House: the Committee on Public Information. Bernays later became publicity director for the New York World’s Fair of 1939. In his book Propaganda (1928), Bernays had already considered a different term for the concept of propaganda; due to the negative connotations the word had obtained after World War I, he proposed to refer to propaganda as the “public relations industry”.

Through this concept of public relations, Bernays brilliantly connected the dangers that representative politics posed to democratism, and the risk involved in the blatant exhibition of power by the Nazis and the Soviets at the Paris World’s Fair. He left the concept of propaganda to the “totalitarian” states in order to enforce the sense of an absolute distinction between dictatorship and to the free world. Instead of the overt authoritarianism of dictators, he proposed the idea of an “invisible government”.

What Bernays took from Wellington House was the idea of a far-reaching, invisible infrastructure that could govern society. But instead of seeing this type of “secret governance” as something limited to a state of emergency, Bernays declared a state of total propaganda in both war and peacetime. Moreover, he believed that the problem of total war, as a product of modern technological society, could only be solved by propaganda. Indeed, Bernays considered propaganda the one and only “democratic” way to deal with the unpredictable, anxious masses. The public relations industry’s primary task was to “manufacture consent,” to understand what the masses wanted even before they knew it themselves. -

Democracity

(New York 1939)

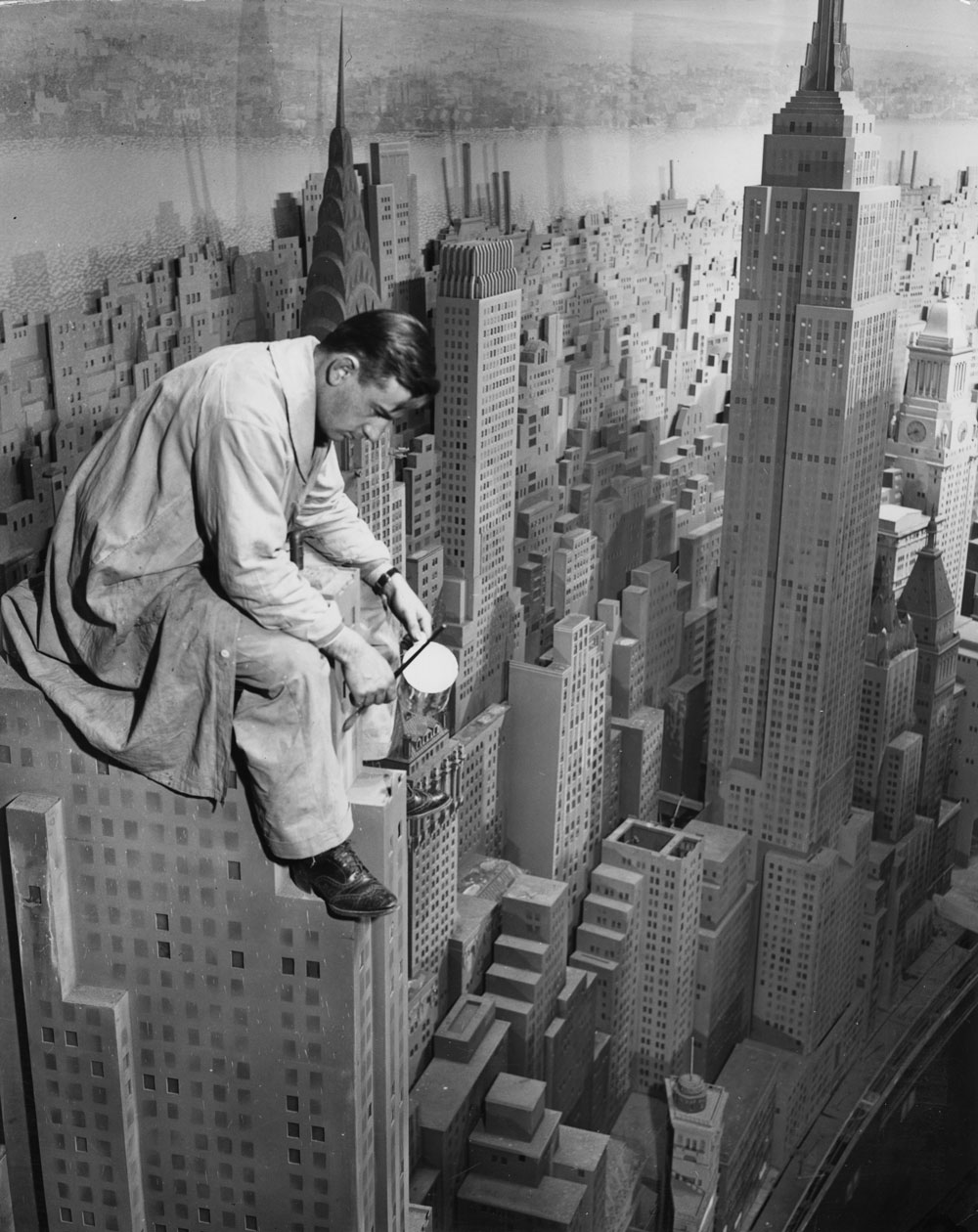

Bernays predicted the future of democratism, with the world fair as its prototype. His vision formed the centrepiece of the New York World’s Fair. Entitled “The World of Tomorrow”, the fair featured national as well as corporate pavilions. At the heart of the fair was a massive structure called the Trylon and Perisphere, which at the time was one of the tallest buildings in New York. Visitors entered the construction through an electric staircase, and once inside they encountered a gigantic rotating architectural model of the city of the future: Democracity, designed by Henry Dreyfuss and crafted in accordance with Bernays’s notion of invisible government.The colossal model of “Democracity”, encased within the walls of the Perisphere featured on the cover.

-

The model embodied a utopian urban structure made possible through the replacement of representative government by the corporate rule of the public relations industry. It neatly separated the different needs of its inhabitants into zones, consisting of Centerton (the social and cultural centre), the Pleasantvilles (middle class residential towns), Milvilles (industrial towns), and Farms, with proximity to Democracity’s city centre determined by class position (the Pleasantvilles being the most luxurious and thus the nearest to Centerton). In Democracity’s brochure, writer and cultural critic Gilbert Seldes adopted the tone of real estate promotional materials when he wrote: “If Democracity were Utopia, government would be superfluous…The City of Tomorrow which lies below you is as harmonious as the stars in their courses overhead. No anarchy – destroying the freedom of others – can exist here”.

The resemblances between Democracity and the ideal of the modernist city as elaborated by the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM), an organisation founded by Le Corbusier [and others] in 1928, are striking. The central premise of the CIAM doctrine is indeed the zoning of the city into different typologies of social activity – such as housing, work, recreation, and traffic. But whereas CIAM planned these social units on an anticapitalist and egalitarian basis, Bernays believed that it was through capitalism – which he considered inherently democratic – that we would arrive at a society of “independent and therefore interdependent men”.![]()

Artist at work on the “World’s Largest Diorama”, the Con Edison “City of Light”

-

Jonas Staal (born in 1981, Zwolle) is a Dutch visual artist and founder of the artistic and political organisation New World Summit. His work deals with the relationship between art, politics, and ideology.

jonasstaal.nl

newworldsummit.euThis is an abridged version of the essay Art. Democratism. Propaganda., that appeared in e-flux journal No.52, 2014 as part of Staal’s project Ideological Guide to the Venice Biennial. Reproduced by kind permission.

![]()

The Trylon and Perisphere at the centre of the 1939 New York World’s Fair site.

What Bernays described was basically the replacement of the state by corporations – corporations being natural democratic entities insofar as they can represent the desires of the people in a way that governments cannot. This is crucial in order to understand the governance of the modern democracity, for in actuality it is not a city, but rather a corporation in the form of a city.

This links the 1939 World’s Fair to the planned World Expo 2020 in Dubai: a city engineered by an invisible government of family-owned corporations and public relations industries, which intervenes in the lives of its people only when the construction of skyscrapers and artificial palm-shaped beaches is threatened by strikes or other forms of political organising.

It is hardly surprising that Dubai won the bid to host the Expo. Dubai embodies the world fair precisely as it was originally conceived: a democratic event without parliamentary democracy. At first glance, Dubai seems to exemplify the ideal of a multicultural society. However, Dubai – which is really a corporation in the form of a state led by the Maktoum family – can only exemplify this ideal as long as the ruling structure underlying it remains uncontested. The Maktoum family has dreamed the dream of democratism: to host a world fair that will uphold, through culture and industry, the formal appearance of democracy, without having to actually go through the trouble of elections. I -

The empty-eyed gaze of this building’s façade, with the insistent repetitive blankness of its stacked rows of arched openings, is a powerful, pure and slightly absurd merging of rationalist modernism, Imperial Roman grandeur, and the stillness of a De Chirico painting: of beauty with bombast.

Rapidly gaining the nickname of Colosseo Quadrato (the Square Coliseum), the Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana or Palace of Italian Civilisation, was designed by architects Giovanni Guerrini, Ernesto Bruno La Padula and Mario Romana for the 1942 Esposizione Universale Roma, Mussolini’s Expo to celebrate 20 years of Fascism and the “return of the Roman Empire” which was thankfully cancelled due to the Second World War.

Clad in travertine stone, allegedly the six by nine arched formation on each of its four sides was not accidental but reflected the number of letters in Benito Mussolini’s names. It was designed to be the centrepiece, not just of the Esposizione, but of a whole new district for Rome, later known as EUR. However had the Exposizione gone ahead, this Palace would have remained a bit player, dwarfed by the colossal Arch of Empire, designed by Pier Luigi Nervi and Adelchi Cirella, which was planned to be 240 metres high and span 600 metres, and intended to rival the Eiffel Tower.

In a new chapter for the building, it will soon reopen as the headquarters of fashion label, Fendi – a comment perhaps of where the money is now in Italian culture. I (rgw)

![]()

Photo: Wikicommons/CC BY-SA 3.0

-

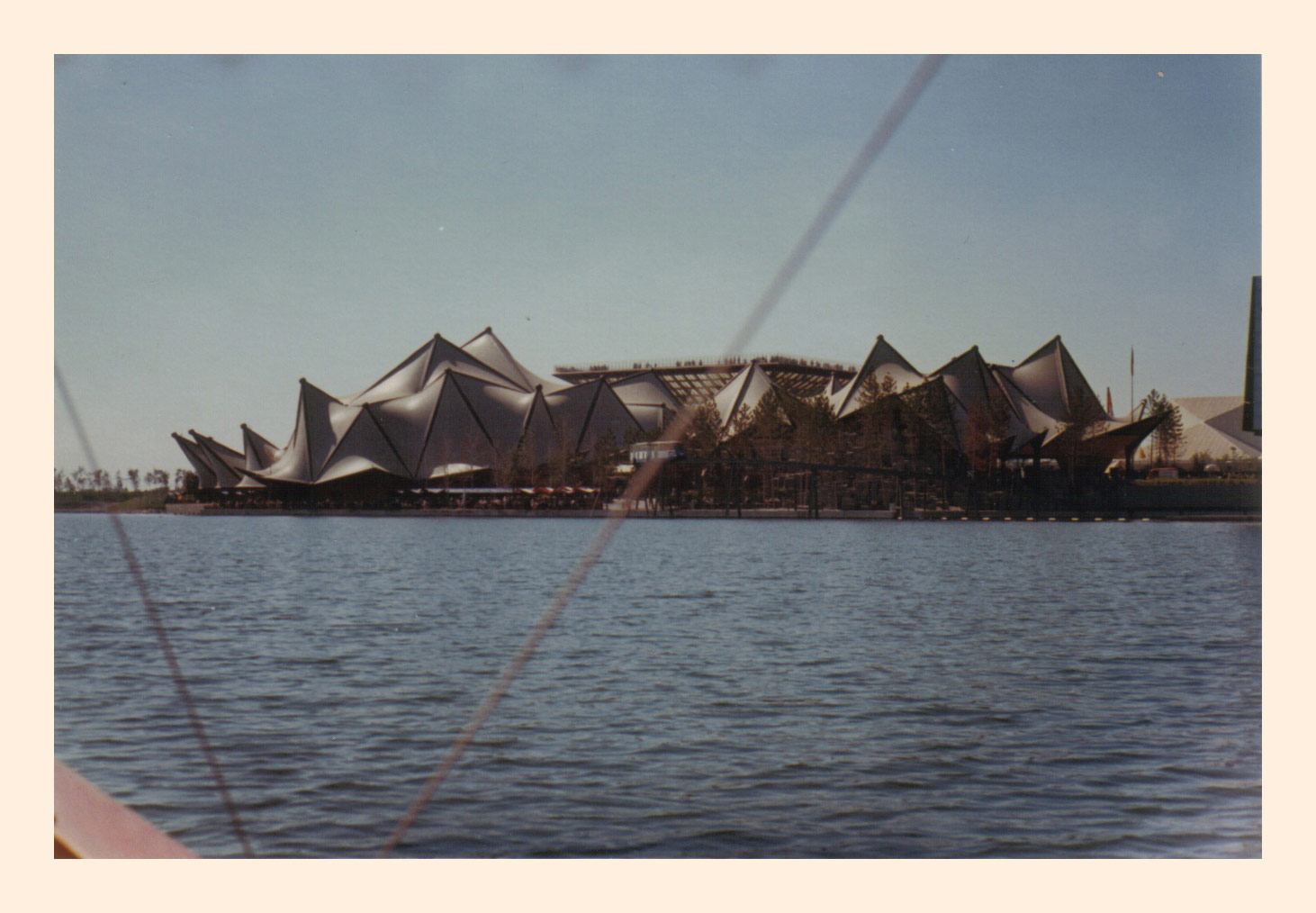

![]()

Montreal Expo, 1967

Text by Mark Kingwell

Photography by Lillian Seymour -

![]()

View of the Gyrotron within the Children’s World amusement park

Canadian political and cultural philosopher Mark Kingwell reminisces about a national extravaganza that he never got to visit and in retrospect finds it to have been a chimera of cheerful optimism.

Here is my key memory of the 1967 Montreal World’s Fair: while my parents planned a visit to this global spectacle of an event commemorating Canada’s centenary, a watershed moment when my chronically insecure country was without doubt the coolest place on Earth, I was parked at my grandmother’s bungalow in the dull eastern reaches of suburban Toronto. It’s true I was only four years old, and thus likely incapable of appreciating the wonders erected on the island city in the Saint Lawrence River; nevertheless, I still resent a little bit that my parents went to Expo and all I got was a lousy key chain.

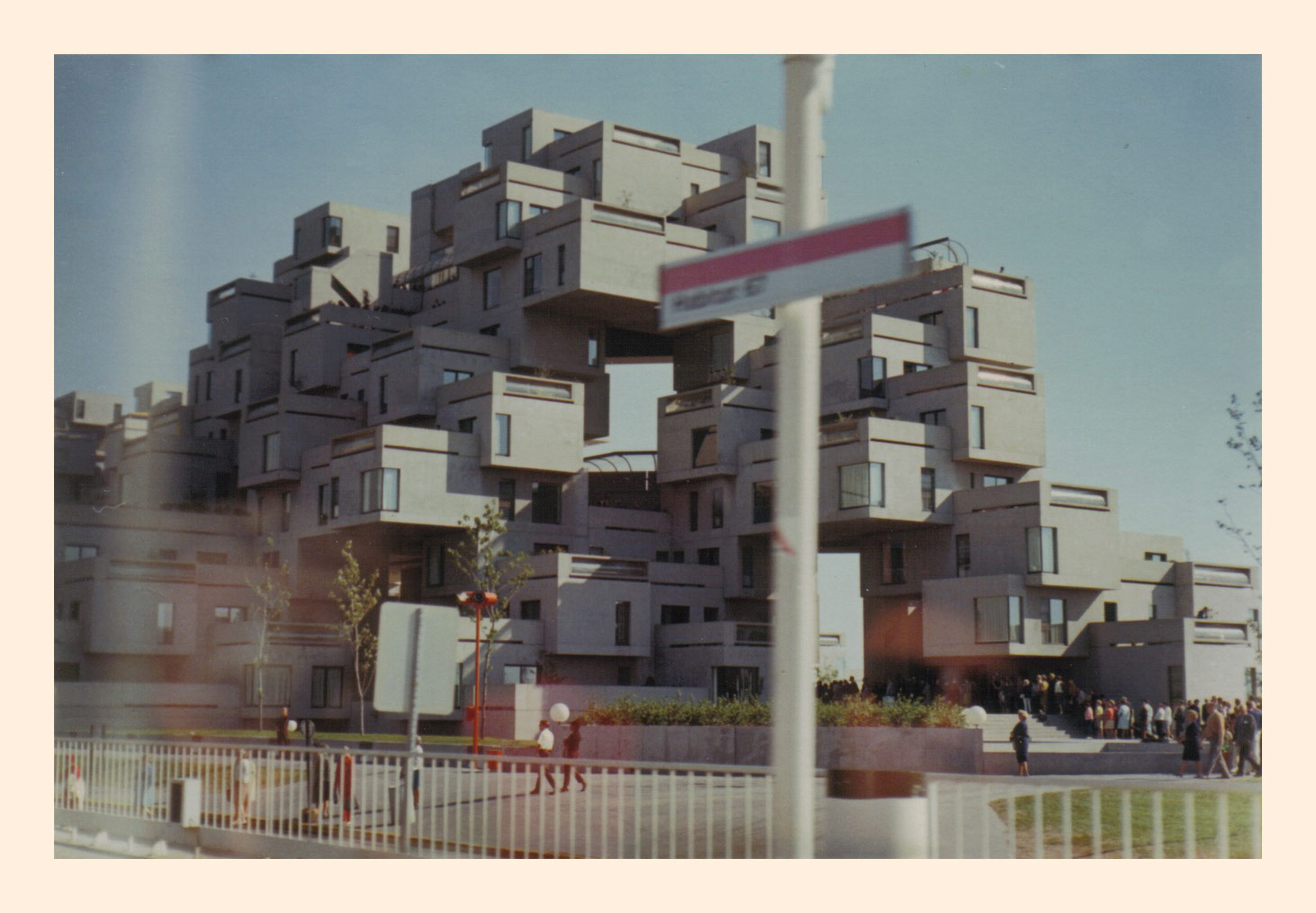

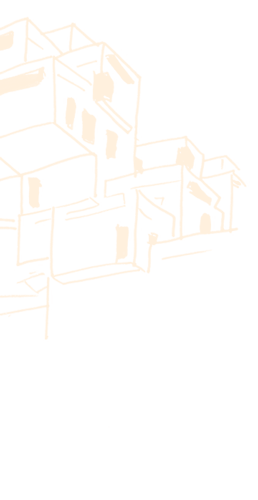

I kept the key chain for years, however, and grew progressively more fascinated with the signature forms of that Fair, to me as instantly signifying as the Trylon and Perisphere of the 1939 New York World's Fair, that celebration of “the world of tomorrow”. In Montreal, Moshe Safdie’s beautifully modular Habitat housing scheme, the glass inverted-pyramid Katimavik building, and Buckminster Fuller’s signature geodesic-dome pavilion for the United States all realised, via architectural imagination, the space-era togetherness of the New Age. The vision was straight out of the toy box of urban construction sets like Super City, the sort of toy I would myself enjoy in a few years, with their future-is-now geometric silhouettes and clean, soaring curtain-wall towers.

Expo ’67 was the shiny side of the coin for that troubled decade, a vision of city harmony and smooth technological progress that ventured to cash in the “democracity” promissory notes of 1939. The 1967 fair’s official theme, “Man and His World”, was taken from a text by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, the visionary aviator, children’s literature author, and closet fascist, but it smacked likewise of Marshall McLuhan – by way, somehow, of Teilhard de Chardin. The universal brotherhood of mediated, techno-happy existence! Canada, and the Future, had never been so awesome: die Stadt von Morgen, but here today.All images: Lillian Seymour via Austin Hall (CC BY-SA 2.0)

-

![]()

A hovercraft demonstration with the Man the Explorer Pavilion in the background

![]()

-

Never mind, then, that many American cities were suffering waves of white flight, eviscerating the downtowns of Detroit, Philadelphia, Buffalo, Cleveland, and a host of lesser cities. Two years later a human being would walk on the moon, but the very next year would witness the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy.

Closer to home, even as the bright strains of Bobby Gimby’s hit song “Ca-na-da” sprang from transistor radios across the nation the Front de libération du Québec threatened to disrupt the fair. Over the next three years, spurred in part by French President Charles de Gaulle’s notorious shout from the balcony of the Old City Hall in July of 1967, “Vive le Québec libre”, the FLQ would bomb, kidnap and kill in the name of Québec separatism. By the time Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau invoked the draconian War Measures Act in October 1970, and tanks rolled onto the streets of Montreal, the cheerful optimism of the Expo summer had evaporated entirely.

The site of the fair, meanwhile, has suffered the usual depredations of time and civic neglect. Even though Expo ’67 managed to avoid the typical cost overruns and corruption-drive Montreal boondoggles that cripple municipal projects in Canada’s showcase city (the 1976 Olympics are a case in point, with stadium debts still on the books decades later), the modest financial success of the Fair did not translate into lasting cityscape. In part this failure is rooted in the original Ile Notre Dame location, which is neither easily accessible nor part of the city’s core urban fabric. Safdie’s Habitat development was sold to private investors and made into a fashionable, if remote, condominium community in 1985. Fuller’s dome was partially destroyed by fire in 1976, and began to resemble a dystopian science-fiction film set and so prompted, as is so often is the case with the forward-looking design, a feeling of inverted nostalgia, the future in ruins.![]()

![]()

The British Pavilion, architect Basil Spence

-

![]()

Habitat 67, architect Moshe Safdie

![]()

-

![]()

The Canadian Pavilion aka the Katimavik

![]()

Expo ‘67 main entrance

![]()

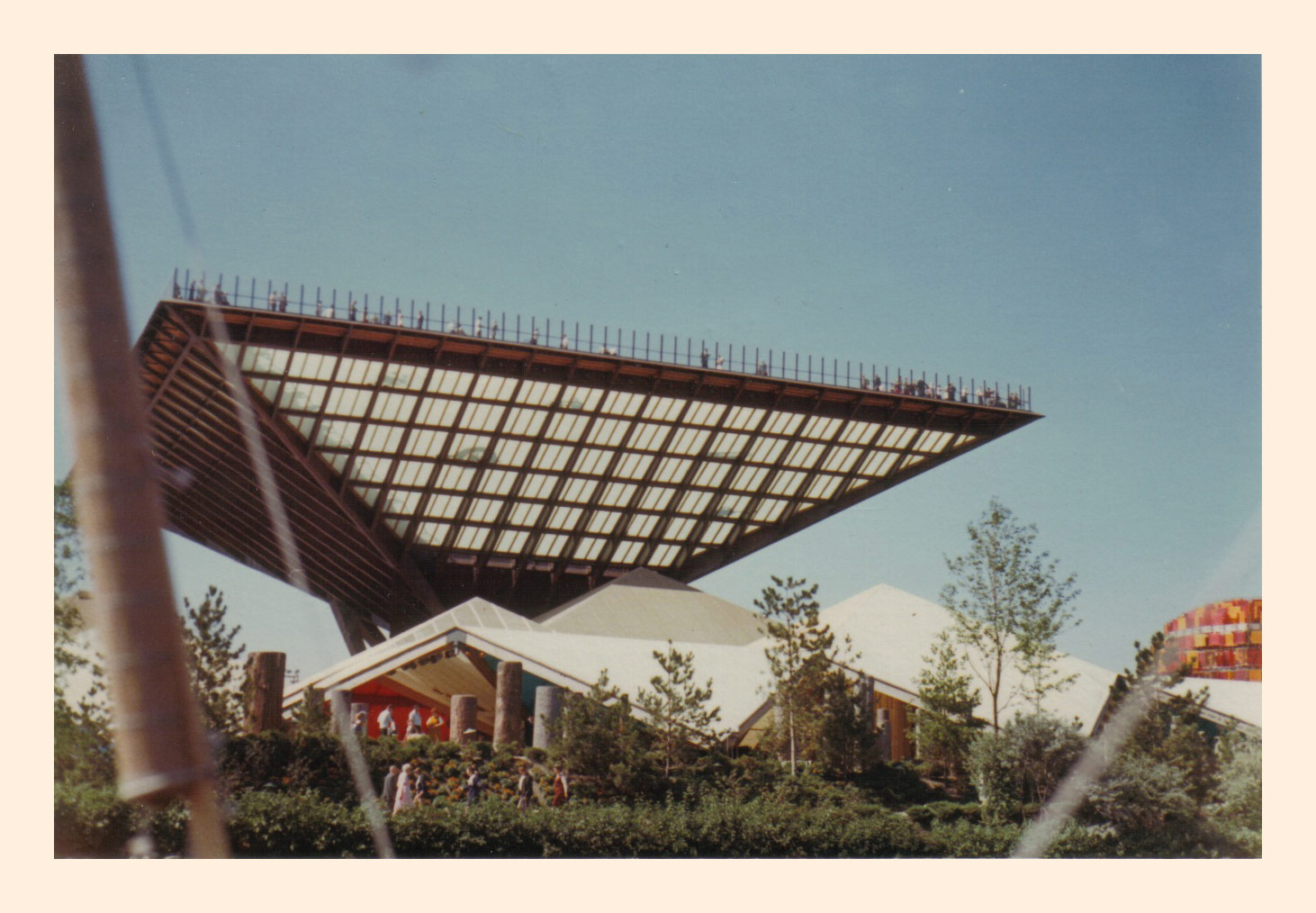

The Japanese Pavilion

![]()

The Ontario Pavilion

-

![]()

The Niger Pavilion

![]()

-

Mark Kingwell is a Professor of Philosophy at the University of Toronto and a contributing editor of Harper’s Magazine in New York. He is the author or co-author of seventeen books of political, cultural and aesthetic theory, including the bestsellers Better Living (1998), The World We Want (2000), Concrete Reveries (2008), and Glenn Gould (2009). In addition to many scholarly articles, his writing has appeared in more than 40 mainstream publications, including Harper’s, the New York Times, the New York Post, the Wall Street Journal, the Guardian, Utne Reader, BookForum, the Toronto Star and Queen’s Quarterly; he is also a former columnist for Adbusters, the National Post, and the Globe and Mail. Professor Kingwell's most recent book is a collection of essays on politics, Unruly Voices (2012); a new collection of his essays, Measure Yourself Against the Earth, will appear in September 2015.

Lillian Seymour is the assumed author of the photographs that appear alongside Mark Kingwell’s essay. The images were discovered within a scrapbook lying in the street in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 2006. As well as a trip to the Montreal Expo in 1967, the album reveals that Lillian had also visited New York’s 1964 Expo. They were scanned and uploaded to Flickr under a Creative Commons license by Austin Hall.

![]()

The Russian Pavilion and Buckminster Fuller Dome

![]()

The Yuguslavian Pavilion

The actual global megacities of the coming millennium would bear some aesthetic kinship to the Expo vision. In Kuala Lumpur, Shanghai, Taipei and Dubai, among others, whole neighbourhoods of impossibly tall buildings now stand, erected with such speed that they feel like the result of a city-building computer programme on overheated download. But the universal togetherness of the Expo vision, the optimistic notion that such architectural wonders would house and serve a new, forward-thinking humanity –“man and his world” indeed! – has been repeatedly demolished by wealth inequality, racism, terrorism and economic collapse. Sitting atop one of these new-world-order urban towers, admiring the polluted views and maybe sipping a drink, the lucky and privileged, and probably male, citoyens du monde among us can indulge the dreams of man and his world. I confess I have done it myself. But any return to the base of the tower involves a rude awakening. As the writer William Gibson has put it, the future is here; it’s just unevenly distributed. So what else is new? I

-

“Our culture, our knowledge and our lifestyle encapsulated.” That was the formidable task assigned to two cauldron-like vessels in 1968 during the first meeting of the Expo ’70 Time Capsule Committee sponsored by Panasonic Corporation and Mainichi Newspapers.

Two sets of 2,098 items were selected for burial, including various samples of synthetic materials, foodstuffs and toys, documentation of the atomic bomb, Japanese coins and flag, the contents of a ladies’ handbag and a pair of slippers. The entire collection was then sterilised using ethylene oxide gas, or in some cases, such as that of the katsuobushi (dried, fermented tuna), via exposure to cobalt-60 radiation, before being buried in the two spherical, stainless-steel containers at the Osaka Castle Park site.

A Tutankhamun’s tomb of the twentieth century (without the body obviously), one of the capsules is to remain buried for 5,000 years for posterity and the benefit of our descendants. The other, containing its matching set of contents, was re-opened for the first time in 2000 and will be opened again every 100 years hence – because five millennia are an awfully long time to wait for seventies fashions to come round again.

But in 6970 AD, when the time is ripe, those unearthing the relics will be greeted with what the committee dubbed the “1970 Rosetta Stone” written in Chinese, English, French, Russian and Spanish and signed by those “who believe in the prosperity of Mankind” in the hope that future beings will appreciate “the particular spirit of the year 1970 AD”. I (fs)

panasonic.net

Photo courtesy The Mainichi Newspapers Co‚ Ltd. / Panasonic Corporation.

-

![]()

![]()

Osaka Expo, 1970

By Crystal Bennes

The Fuji Group Pavilion. (Photo courtesy Bill Cotter)

-

![]()

Flying in on the fanciful coat tails of space age optimism and 1960s socially-minded utopianism, the Osaka Expo 70 can be considered the last of the great, experimental expositions before finite resources and techno-progressive pragmatism began to dominate the agenda. Crystal Bennes investigates an Expo future vision that revolved around Buckminster Fuller spheres and Metabolist cells.

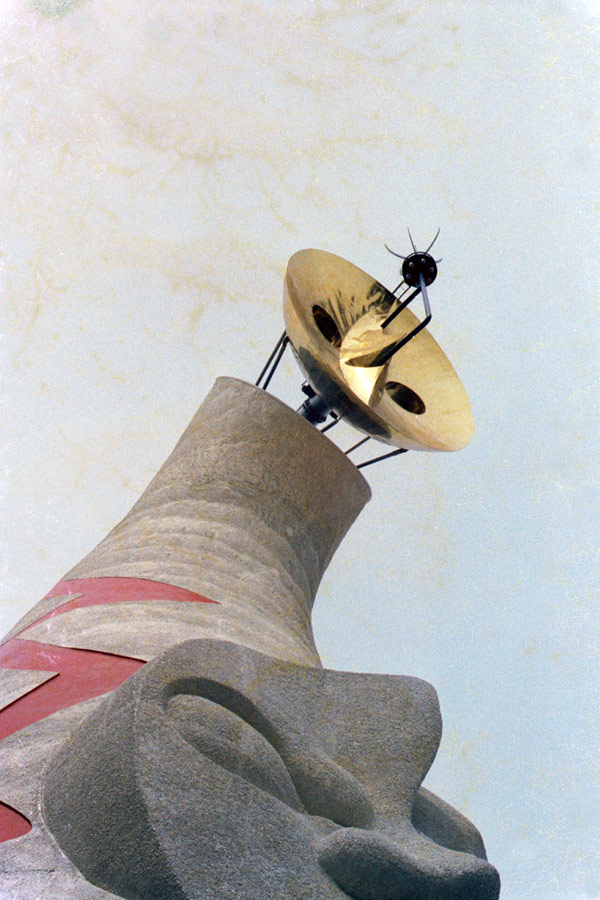

Taro Okamoto’s “Tower of the Sun”. (Photo: Henry Petermann)

-

Defined by a pervasive sense of architectural risk-taking and experimentation, both in its ideology and design, it’s hardly surprising that, forty-five years on, images of the 1970 World’s Fair in Osaka look as fresh, even futuristic, as ever. The first Expo to be hosted by an Asian nation, the theme of Osaka 70 was “Progress and Harmony for Mankind”. Leading a team of 11, including fellow Metabolists, Kikutake Kiyonori and Kurokawa Kisho, as well as artist Taro Okamoto, a key figure of the Japanese avant-garde, Kenzo Tange was the man responsible for the suitably progressive masterplan.

Tange rose to prominence in Japan with his design for the 1955 Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, as well as stadiums for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics often described as some of the most beautiful structures built in the twentieth century. By 1960, he had begun to shift focus from individual buildings to urban development, designing ambitious plans to redevelop Tokyo’s infrastructure and housing on a grand scale.![]()

“Tower of the Sun” detail (Photo: Flickr/m-louis* CC BY-SA 2.0)

If post war Japan offered few opportunities for Tange to realise such plans in reality, the 1970 Expo presented at least an opportunity to test some ideas on a larger platform.

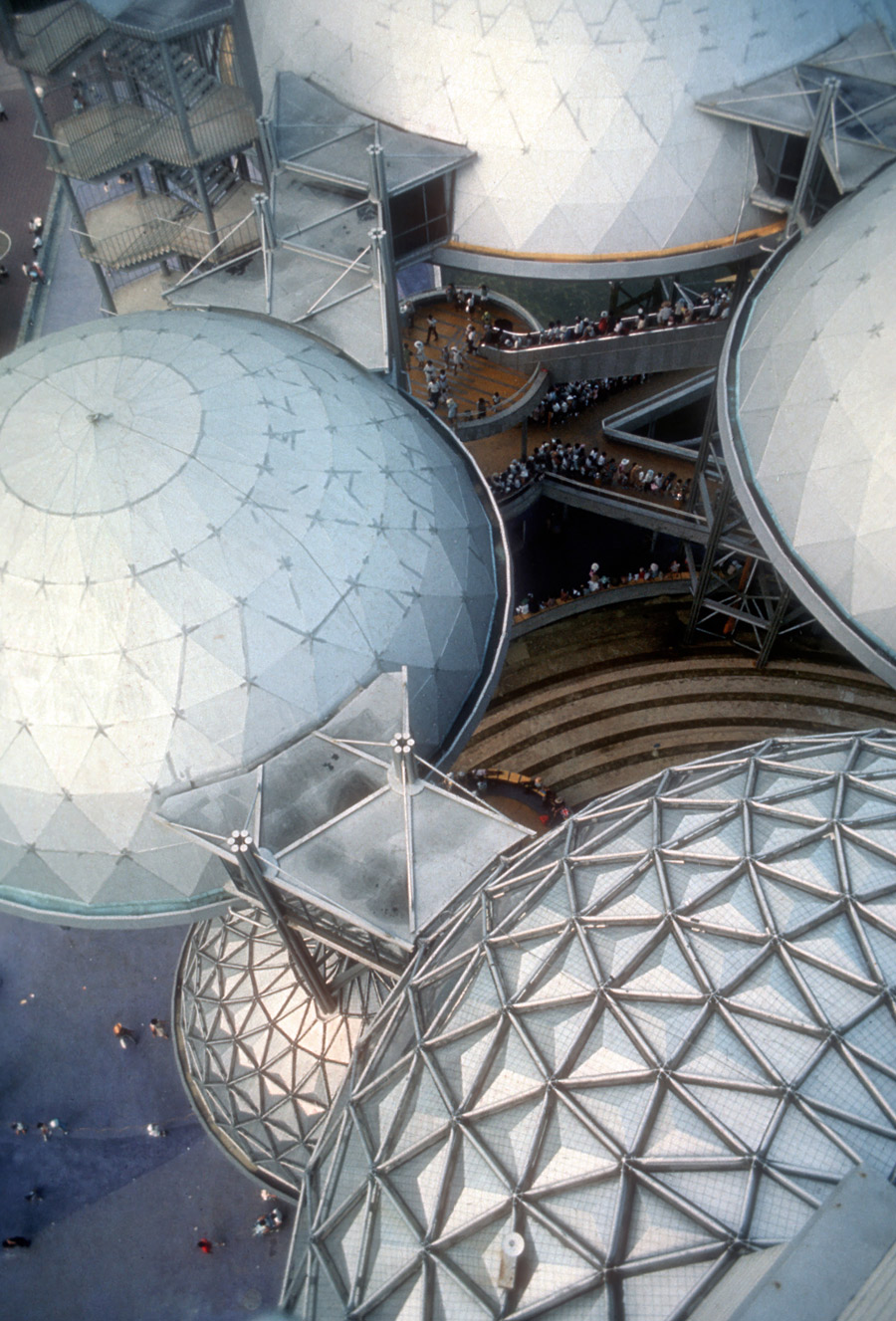

Inspired by the vaulting, unifying roof of Joseph Paxton′s 1851 Crystal Palace and propelled by Buckminster Fuller’s developments of Alexander Graham Bell’s space frame, Tange’s most visible Expo contribution was a giant roof for the Festival Plaza – at the time, the largest space frame structure ever constructed. For Tange, the vast frame was a symbolic link between the Festival Plaza and the other structures, unifying this spatially, while allowing pavilions their own visual identities outside the frame. Conceiving of the Expo as a festival “where human beings can meet, shake hands and accord minds”, he saw the plaza as an important central site for such activity, “contributing to the development of this festival of human harmony”.

-

The Toshiba IHI Pavilion, designed by Kurokawa Kisho. (Photo: Flickr/m-louis*)

-

Artist Taro Okamoto, bearing the 1964 Tokyo Olympics in mind, was conscious that the Expo should engender participation rather than mere spectatorship. Like Tange, he saw the Expo as a “festival” where his “monstrous” monument, The Tower of the Sun, could shock visitors out of the complacency of everyday life: “While Tange Kenzo’s Grand Roof was mechanistic, I created something totally primitive and let it break through the roof… I think ‘anti-harmony’ is real harmony.”

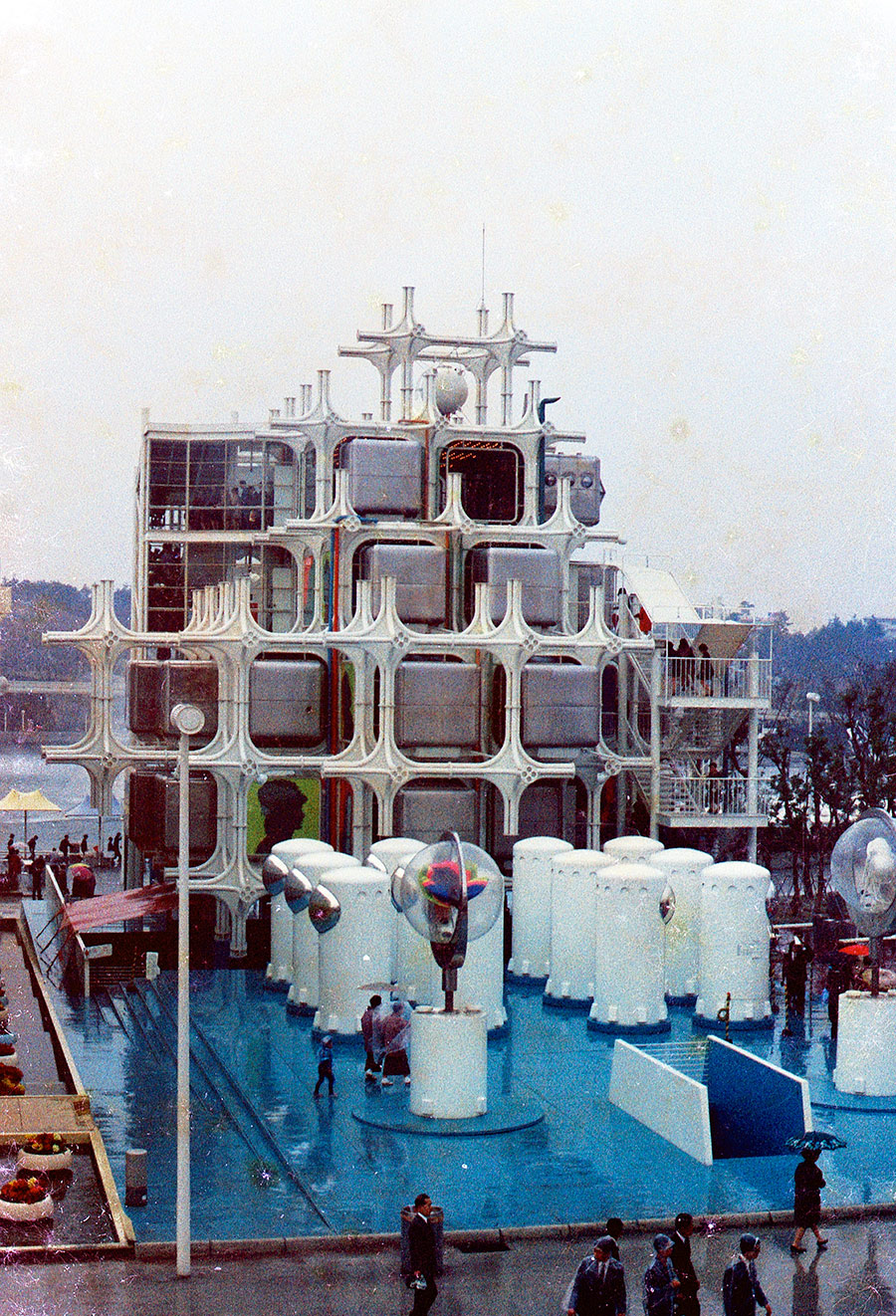

One of the most visible architectural influences across Expo 70 was that of Metabolism, which was formulated a decade earlier by a group of architects including Tange, Kikutake and Kurokawa. Rejecting the fixed proscriptions of form-follows-function modernism, the Metabolists, inspired partly by biological concepts, sought to respond to ever-changing urban environments with systems of interchangeable components. Kurokawa’s contribution to the Expo was textbook Metabolism. His tree-like Takara Beautilion was a steel-framed structure with the “potential to extend, or replicate horizontally and vertically depending on necessity”.

Elsewhere, architectural and structural experimentation seemed to encapsulate the spirit of the early, post-space-age period. The US effort, with its exhibition of Moon rock from the Apollo mission, is one obvious expression. Based on Frei Otto’s experiments with pneumatic structures, architects Davis, Brody, Chermayeff, Geismar, de Harak Associates covered an 80 x 142 metre super-elliptical structure with a translucent fiberglass fabric – held up by nothing more than its own internal air pressure. -

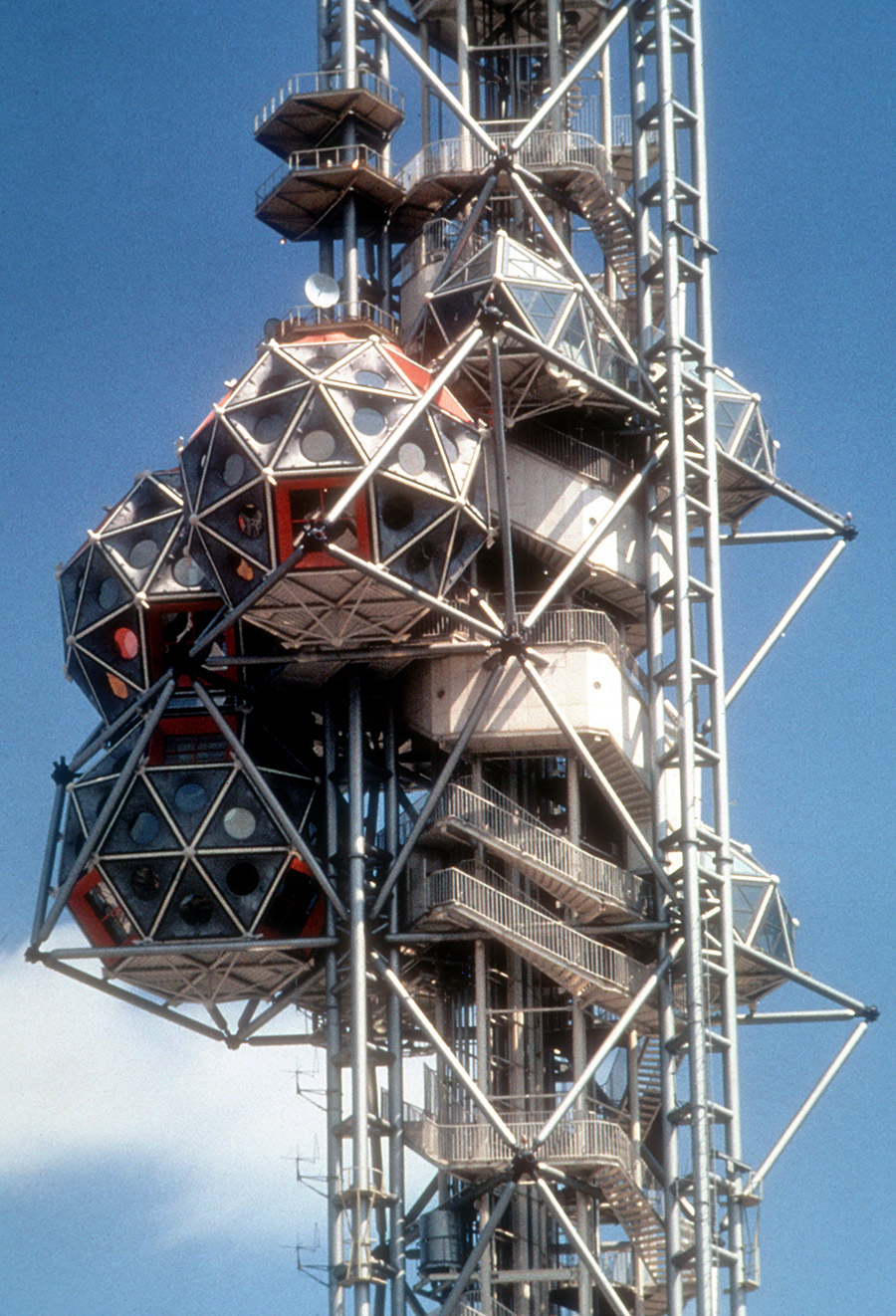

![]() Kiyonari Kikutake's Expo Tower. (Photo courtesy Bill Cotter)

Kiyonari Kikutake's Expo Tower. (Photo courtesy Bill Cotter)![]() The Takara Beautilion, designed by Kisho Kurokawa & Ekuan/GK. (Photo: Flickr/m-louis*)

The Takara Beautilion, designed by Kisho Kurokawa & Ekuan/GK. (Photo: Flickr/m-louis*)![]() The Sumitomo Pavilion, designed by Sachio Otani. (Photo courtesy Bill Cotter)

The Sumitomo Pavilion, designed by Sachio Otani. (Photo courtesy Bill Cotter) -

![]()

1.

Yutaka Murato and engineer Kawaguchi also experimented with pneumatics to striking effect. Their enormous Fuji pavilion, comprised of 16 arches of inflated plastic tubes, was the largest air-inflated structure in the world at the time. Buckminster Fuller’s Octet Truss system inspired more than just Tange’s space frame, and many pavilions took the form of a geodesic dome – notably Fritz Bornemann’s spherical concert hall for the West German pavilion and the nine half-domes of Sachio Otani’s Sumitomo Fairy Tale pavilion. In other cases, innovation emerged for unusual reasons, such as E.A.T.’s project by physicist Thomas Lee and artist Fujiko Nakaya to cloak Tadashi Doi’s faceted Pepsi pavilion dome – which they loathed – in artificial clouds.

![]()

2.

![]()

3.

All photos on this and following page: Henry Petermann

![]()

4.

-

![]()

![]()

5.

![]()

6.

![]()

7.

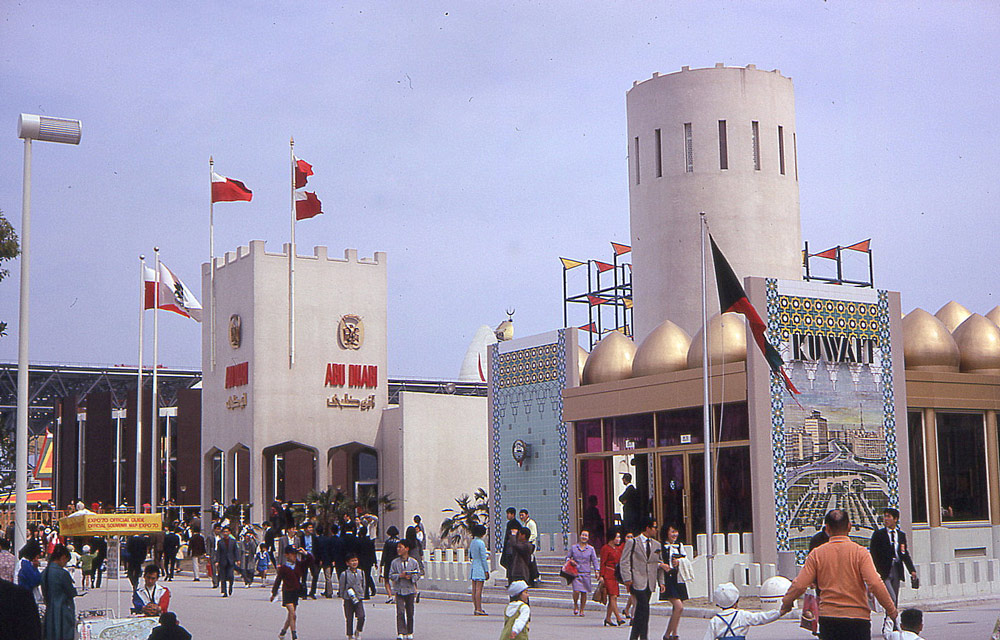

1. Abu Dhabi and Kuwait pavilions

2. View towards the site’s amusement zone: “Expoland”.

3. Laos Pavilion

4. USSR Pavilion, designed by Mikhail V. Posokhin.

5. Mexico Pavilion

6. Netherlands Pavilion by Jaap Bakema and Carel Weeber.

7. Cambodia Pavilion -

Photo: Henry Petermann

-

Crystal Bennes is a writer, curator and artist based in Finland and a contributing editor to uncube. Along with Cecilia Lindgren, she is co-editor of independent culture and urbanism magazine, Pages Of, and contributing editor of Icon magazine. She runs the blog Development Aesthetics and is one third of the London Research Kitchen.

The Osaka Expo is often considered the last of the great, experimental expositions. If there’s truth in such claims, it’s interesting to consider the reasons why. Many architectural historians view the 1960s as a golden age of socially-minded architecture, a time when architects were thinking how people could live better lives and how architecture could involve itself in the realisation of such activity.

And yet, if the 1960s were a golden age – and Osaka its apex – such goldenness was only possible due to a certain degree of ignorance. The period immediately following the Expo saw the 1972 publication of The Limits to Growth, an influential report simulating exponential economic and population growth in a world of finite resources, and then came the 1973 oil crisis. In this new era, informed by scarcity and increasing recognition of the impossibility of infinite growth, focus shifted away from experimental, futuristic social utopias towards networked, techno-progressive pragmatism.

The following Expo, held in Spokane, Washington, USA in 1974, was the first to take up an explicitly environmental theme, and marked the beginning of the end for the spectacular, structural-engineering-driven showpieces that were the hallmark of Osaka. While on the surface innovation and experimentation continues to be encouraged, the reality is that – for better or worse – sustainability, technological interactivity and networked systems have become the new face of “experimental” expo architecture. I -

![]()

![]()

Hanover Expo, 2000

By Rob Wilson

View of MVRDV's Dutch Pavilion at the Hanover Expo site, as it looks today. (Photo: Ives Maes)

-

What makes a successful Expo? Financially and in terms of visitor numbers, Expo 2000 was a flop but it scored when it came to recycling after the event. Rob Wilson looks beyond the bling towards cultural values, infrastructural advantages and small footprints.

![]()

Just as abandoned fairgrounds often serve well as creepy settings for horror films, the derelict bones of old expos look particularly macabre: decayed carcasses of once spectacular structures built to fizz with positivity and ideas for the future. One example of this is the MVRDV-designed Dutch Pavilion from Expo 2000 in Hanover, Germany, once star of the show, now a forlorn, rotting shell.

With its theme of “Holland Creates Space”, responding to the Expo’s one of “Humankind, Nature, Technology”, the Dutch pavilion was a 36-metre-high tower of six stacked landscapes symbolising and demonstrating how to maximise the use of limited space. Visitors moved up through its tulip fields to a small lake at the top, where windmills ran turbines powering the structure.

Originally the plan post-Expo had been to dismantle and re-erect the building in the Netherlands, but this was deemed too costly. With even demolition proving expensive, the pavilion was apparently given away with a cash dowry to a man who promised to give it a second lease of life. Later this recipient tried unsuccessfully to sell the pavilion on eBay, and now it is owned by his son, seemingly too cash-strapped to either renovate or demolish it.

With a touch of schadenfreude, the pavilion’s remains might seem a fitting monument to misplaced millennial optimism and the symbolic legacy of Expo 2000, widely seen as a relative failure at the time: only 18 million tickets were sold against a projected 40 million (compared to the 64 million in Osaka in 1970 or Shanghai Expo 2010’s 73 million) and it ended with a financial deficit of some 3,900 million deutschmarks. But the story of ambitious legacy intentions before the event, later overtaken by any ad hoc needs-must solutions going, is a familiar one post-Expo. -

![]()

MVRDV’s Dutch Pavilion interior today. (Photo: Ives Maes)![]()

MVRDV’s Dutch Pavilion exterior today. (Photo: Hagen Stier) -

Indeed Expo 2000 was actually one of the more successful iterations when it came to recycling its old pavilions. Whilst most were demolished, the Belgian Pavilion for instance is now known as the Peppermint Pavilion, housing an event space, recording studio and record company. Meanwhile the Mexican Pavilion popped up in Braunschweig, as the library for the University of the Arts there, while the Nepalese Pavilion was resurrected at the centre of a botanical garden in Bavaria.

In general, the hoped-for legacy of an expo can be roughly grouped into three types. Most importantly, yet ephemerally, is that sense of you-had-to-be-there – both in an individual and folk-memory sense. The feel good factor for those who attend is naturally a key outcome for the countries or corporations bankrolling Expos; for World’s Fairs have always been exercises in either national or commercial soft-power – beaming out messages to their citizens and consumers to influence their future thinking, voting and buying habits»The decayed carcasses of once spectacular structures built to fizz with positivity and ideas for the future«

– be it a cool-contemporary national image for the Weimar Republic, offered by Mies van der Rohe’s German Pavilion in Barcelona in 1929, or the turn on, tune in, drop out, and er, drink Pepsi message of the Pepsi Pavilion designed by E.A.T. for the Osaka Expo in 1970.

Secondly, beyond the spin, Expos have often initiated or promoted actual technical and cultural shifts, either by allowing the space or license to attempt some daring new engineering feat – the moving walkways at the 1900 Paris World Fair, the unprecedented iron girder structure of the Eiffel Tower in 1889 – or by providing a forum where a new visual trend or style can coalesce. The so-called “White City” of Chicago’s 1893 Columbian Exposition set off a global neo-classical revival, while the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris lent its name to the Art Deco movement. -

![]()

The cluster of structures which once served as the Danish Pavilion. (Photo: Flickr/Peter Shacky)

-

»The conundrum for the contemporary Expo is how to deliver a sustainable legacy message from what is, by its nature, a one-off wasteful event«

The former Lithuanian pavilion. (Photo: Hagen Stier)

-

The third type of legacy is the actual, physical, urban knock-on effect for a host city; the seeding of urban expansion or new neighbourhoods through improved infrastructure or through showcasing new models for living: as at the Montreal Expo ’67, with its new Concorde Bridge, monorail and Habitat housing complex, or the laying out of the new EUR district for the (cancelled) 1942 Esposizione Universale in Rome.

Those individual buildings or structures that transcend their Expo genesis and make it to a useful afterlife are usually ones that successfully combine aspects of all these types of legacy, acting as memorable icons, representing technical advances or providing practical future facilities. Paralleling Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown’s observations in Learning from Las Vegas, on that more permanent urban encampment of signs and showstopper attractions, these generally fall into two types: ducks or decorated sheds – structures that symbolically carry a message or embody a brand, easily transferable from Expo to city (usually tall and distinctively profiled e.g. the Atomium in Brussels) or buildings that offer ultra-flexible re-use (usually vast and shed-like e.g. the Grand Palais in Paris).

The 1851 Great Exhibition, the first Expo, still remains the model to beat in terms of delivering on all legacy fronts. It acted as a condenser for Britain’s image as the workshop of the world and transmitted powerful British Empire PR, not only to its six million visitors but also as a worldwide news event: witness all the other countries that jumped to emulate it. It also turned in a healthy profit, which was ploughed back into a new museums’ quarter in Kensington. The innovative cast iron and plate glass structure of the Crystal Palace, designed by Joseph Paxton, both distinctive symbolic duck as well as enormous decorated shed, was rebuilt in extended form in South London, providing a capacious flexible venue for over 80 years until it burned down in 1936, and simultaneously becoming the generator for a whole new London suburb around it.

That all this only happened on the back of the single-minded power trip of the original event is easily critiqued now for its unselfconsciousness nationalism and misplaced belief in linear progress, fuelled by commerce and manufacturing. But this remains the conundrum for the contemporary, “sustainable” Expo of today: how to celebrate human ingenuity yet replace the passion and spectacle generated by national or commercial rivalry in order to attract visitors, and how to deliver a sustainable legacy message from what is, by its nature, a one-off wasteful event. For aside from the über-duck or über-shed exceptions, the appropriate legacy, as with any travelling fair, should be an empty camp site, containing nothing more than the carefully kicked-over embers of a fire. I -

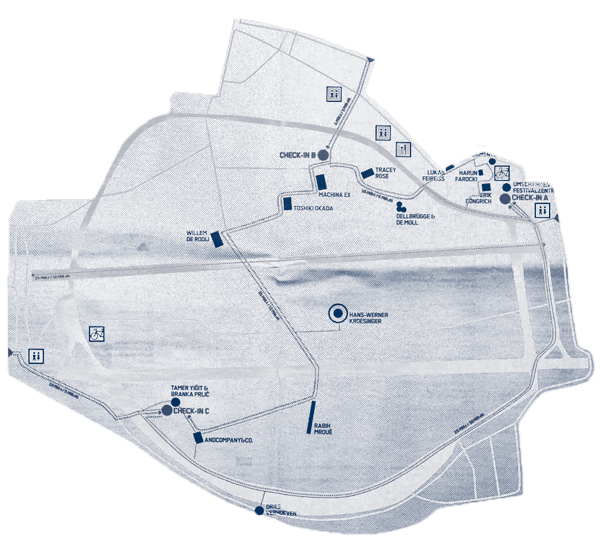

Organised by the architects raumlaborberlin and the Hebbel am Ufer theatre, “The World is Not Fair – The Great World's Fair 2012” was probably the first DIY Expo ever. Fifteen artist groups – mostly from Berlin – build fifteen strange structures spread generously over the vast, flat emptiness of the former Tempelhof airfield in Berlin, throughout the month of June 2012. Some participants used existing structures on the site: a bunker was turned into a cinema, for example, and a former kennel for security dogs became a small performance theatre. Others were built new, from scratch, using low-cost and recycled materials. The “pavilion” pictured here and titled 52.4697°N 13.396°E, was made by artists Branca Prlić and Tamer Yiğit and intended to act as an “assembly point for people without permanent residence”.

This very unofficial “World’s Fair” was as funny, experimental and passionate as it was educative, thought-provoking and political; questioning the meaning, the ambitions, and the aftermath of all the other Expos in a manner that had it punching well above its low-budget weight. I (fh)

raumlabor.net

![]()

DIY Expo

Photo: © Thorsten Klapsch

-

![]()

![]()

Putting an End to the Vanity Fair

Interview with Jacques Herzog

By Florian Heilmeyer

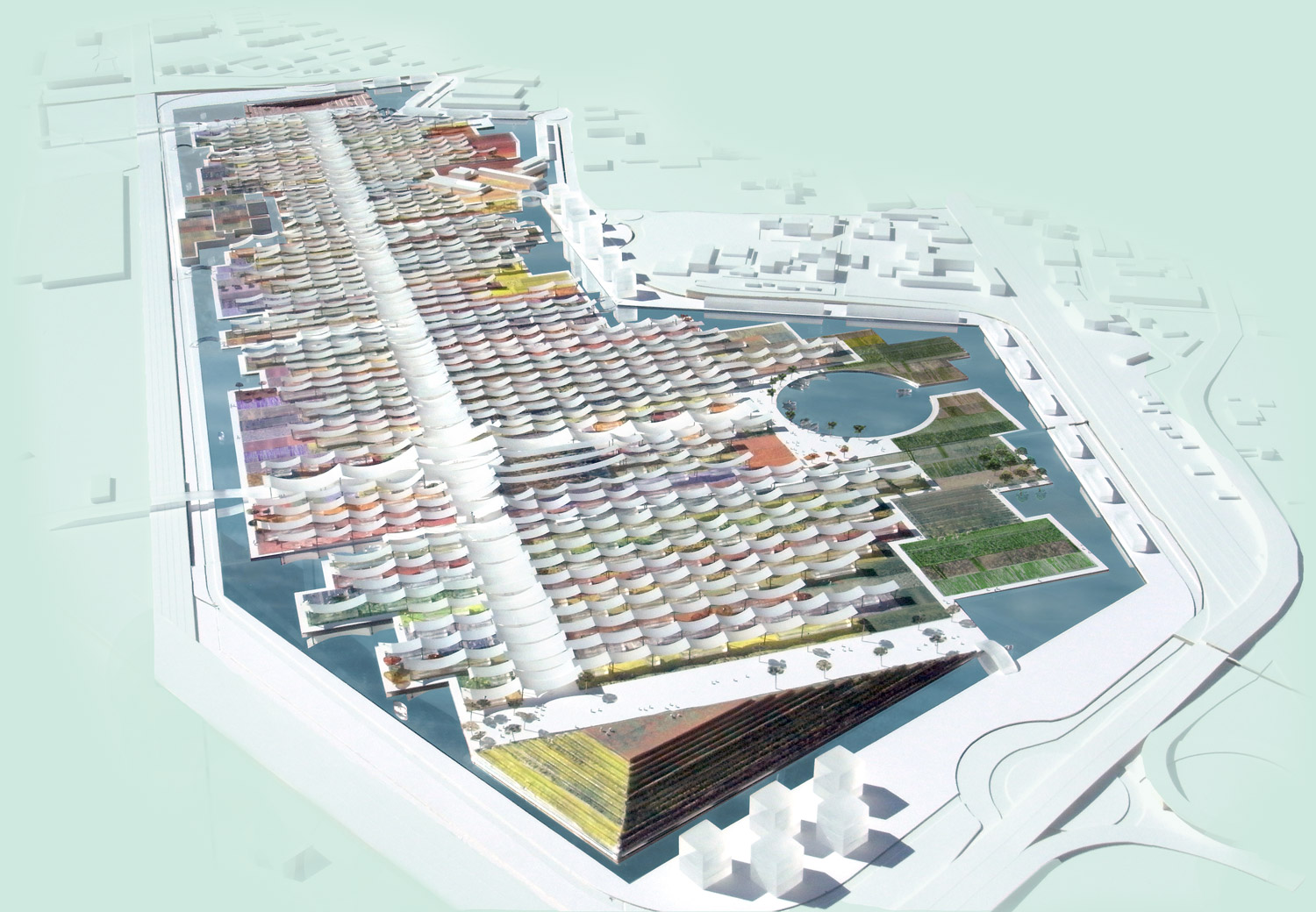

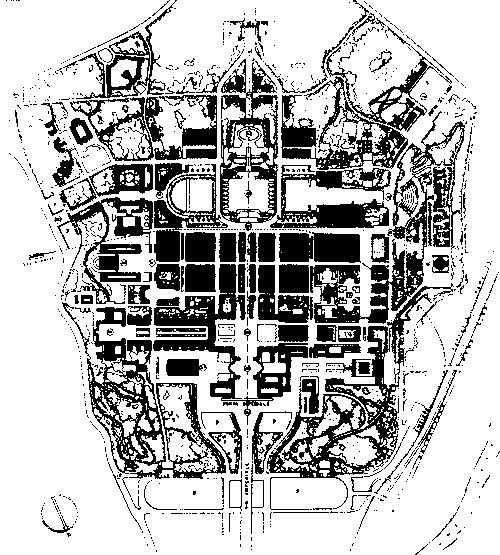

Conceptual masterplan for the Expo 2015 by Stefano Boeri, Herzog & de Meuron, William McDonough and Ricky Burdett.

Image © Herzog & de Meuron

-

![]()

Jacques Herzog. (Photo: Adriano A. Biondo)Stefano Boeri, Herzog & De Meuron, William McDonough and Ricky Burdett were invited to design the masterplan for the Expo 2015 in Milan. By 2011 they had all left the project. In an exclusive interview with uncube, Jacques Herzog explains why.

How did you get involved in designing the masterplan for the Expo 2015 in Milano?

We were invited by Stefano Boeri, who is based in Milan and was commissioned to develop the masterplan. His ambitions were to fundamentally rethink the entire Expo format. The concept of a “World’s Fair” appears to be very outdated. It is a model from the last century, and Stefano really wanted to turn it into an exhibition for the 21st century. So he invited us to work together with William McDonough and Ricky Burdett on this masterplan, because he knew we would share his ambition to radically reinvent the idea of a World’s Fair. He also knew he would need a strong team in order to turn this revolutionary ambition into reality.

What made you think the Expo in Milan would be interested in such a radical and critical approach?I have seen a few World’s Fairs. Particularly the last one in Shanghai in 2010 made it clear to me that these Expos have become huge shows designed merely to attract millions of tourists. A giant area filled with enormous pavilions, one always more spectacular than the other, and these unbelievable vast halls for gastronomy, shops and pissoirs. What a bore and a waste of money and resources! We decided only to accept the invitation to design the Milan masterplan if our client would accept a radically new vision for a world exhibition; abandoning these monuments of individual national pride that have turned all Expos since the mid-nineteenth century into obsolete vanity fairs.

-

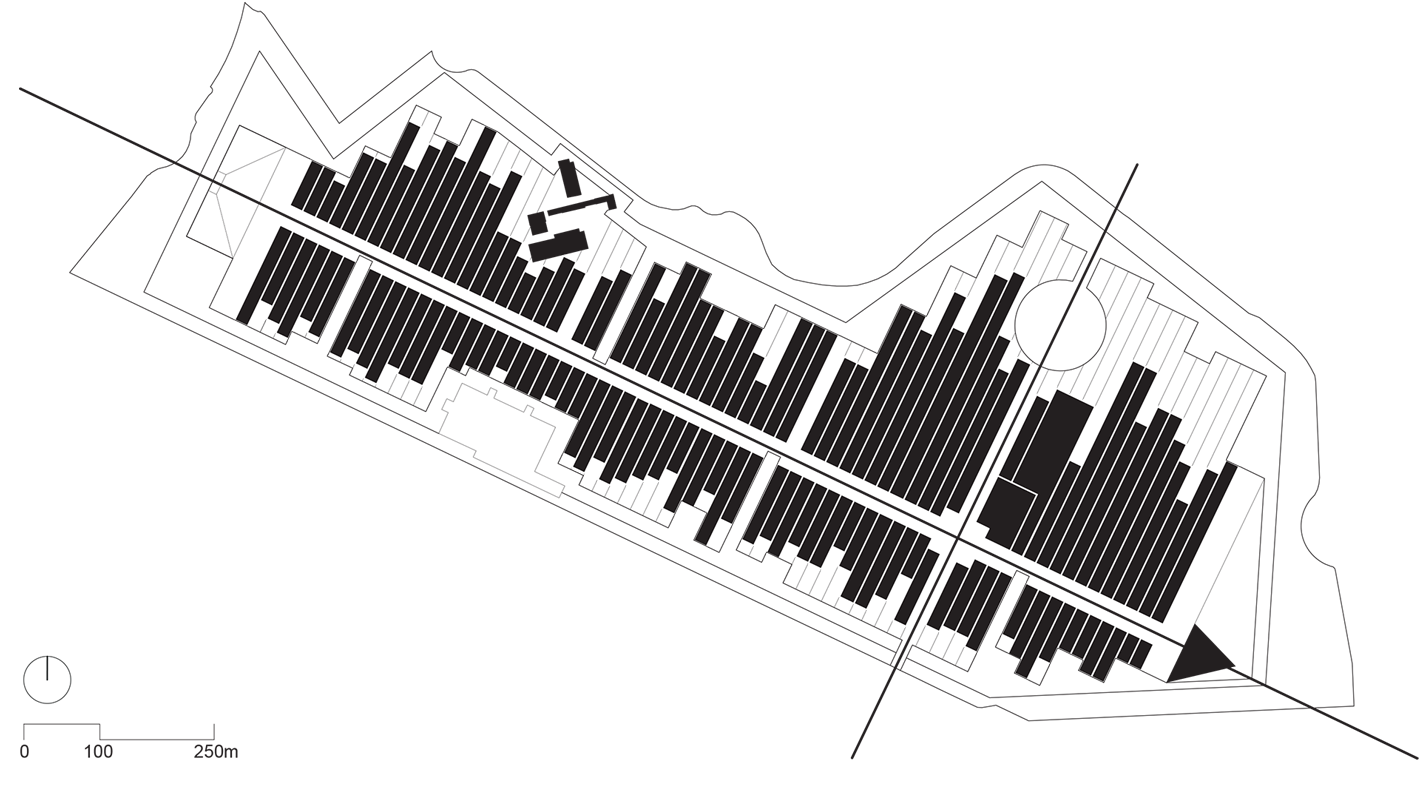

![]()

The original masterplan design – inspired by antique Roman city planning – has two main axes and a grid of long and narrow plots for the national pavilions in an effort to elide the usual vanity fair of competitive “national pride” seen at past Expos. (Image © Herzog & de Meuron)

-

»The content of the exhibitions should make the countries look different, not the size of their pavilions«

Instead we wanted to oblige every participant to channel all their pride into their contribution to the Expo’s theme of “Feeding the Planet”: addressing the important topics of food production, agriculture, water, ecology etc. The content of the exhibitions should make the countries look different, not the size of their pavilions. Also we felt that this expo would be exactly the right place to start focusing on content, because it simply seems embarrassing to address this very important topic and at the same time built enormous, dramatically curved pavilions with facades in wavy plastic or with spectacular waterfalls or whatever. We would much rather know how countries like Kenya, Mexico, China, Laos or Germany are dealing with the question of how to feed their people.

How did your masterplan try to disrupt the dominance of the national pavilion architecture?We suggested a strong basic and generic pattern with two big main axes based on the cardo/decumanus orthogonal grid of the antique Roman city. This would create a grid of extremely long and rather thin plots, with every country having a plot of the same size. We proposed encouraging all participants to present their exhibitions as agricultural gardens with only very simple, basic shacks forming sheltered spaces for their exhibitions. All of this would have been covered by a structure of tent roofs stretching over the entire site, provided by the organisers. This would have resulted in all participants having plots of equal size under the same light roof structure, with no big individual pavilions.

This would indeed have turned the Expo as we know it upside down. Did you really think you could get away with these radical ideas?Our intentions were clear from the very beginning and the organisers understood and supported us. However they were not powerful or courageous enough to convince their own organisation and the responsible politicians to support them.

-

As a consequence they were reluctant to convey that fundamental message to the participating countries to forgo their individual designs and break with the Expo traditions they have all been following for so long now. It was clear to many people that the themes of this Expo deserved to be treated differently, but they were not prepared to follow our guidelines.

So what happened to your masterplan?It became the official basis for the Expo in Milan - yet only as an urbanistic and formal pattern, not as an intellectual concept. The tent roofs we proposed are now covering the main boulevard in front of the national pavilions, which seems an absurd reversing of our ideas. As I said, we are not involved in the realisation of the Expo anymore. From what I have heard about the coming pavilions and concepts, it seems that this Expo will be the same kind of vanity fair that we’ve seen in the past.

What was lacking to have made your concept reality?I cannot put the blame on anyone or anything in particular. All the people we discussed our concept with were quite intelligent and understanding - but bound to their employers and/or voters. I still think that everyone involved at Expo agrees with our critical vision of what a World’s Fair should be and that the basic idea behind it should be kept for the next possible occasion. But when if not there, in Milan, with people like Stefano Boeri and Ricky Burdett on our side, could we convince an Expo client to take that risk?

An event this big (and expensive) has many forces acting upon it and I am not even sure if there ever was a conscious decision against our concept. Maybe it is rather like a swarm of fish swimming in one direction; we tried to navigate it in the other, but somehow they kept swimming. Maybe we should have initiated a diplomatic mission, sending the very talented “diplomat” Ricky Burdett to every single participant, explaining our concept, and to win them over.»I am afraid that the visitors will again be blinded and distracted rather than informed«

-

But this was impossible, and we then realised that the organisers would not – or could not – undertake the necessary steps to make these ideas happen. Since 2011 none of the offices are involved anymore – Boeri, McDonough and Burdett got out, and we decided to end our collaboration with the Expo team that was an almost daily exchange until that moment. The Expo team has dealt with the realisation themselves since then.

Yet the structure will still be based on your ideas. At least that’s what the Expo office tells us. Do you believe that this Expo will be different from the others, even just a little bit?I believe that some countries understood our concept and therefore will put more weight on content than on form. Also, as far as I know there will be 13 NGOs like Oxfam and WWF adding some important topics. But they will have small, modest venues compared to the big global companies like Monsanto, Syngenta, New Holland or Agriculture, which will be present with huge shows – and we can expect similar marketing shows from many of the participating countries. So I am afraid that the visitors will again be blinded and distracted rather than informed and made aware of chances and risks, of opportunities and difficulties, of politics and business, etc. There is an amazing variety of global themes that should be tackled and brought to the fore – the conventional format with national pavillons competing for design awards cannot deliver that!

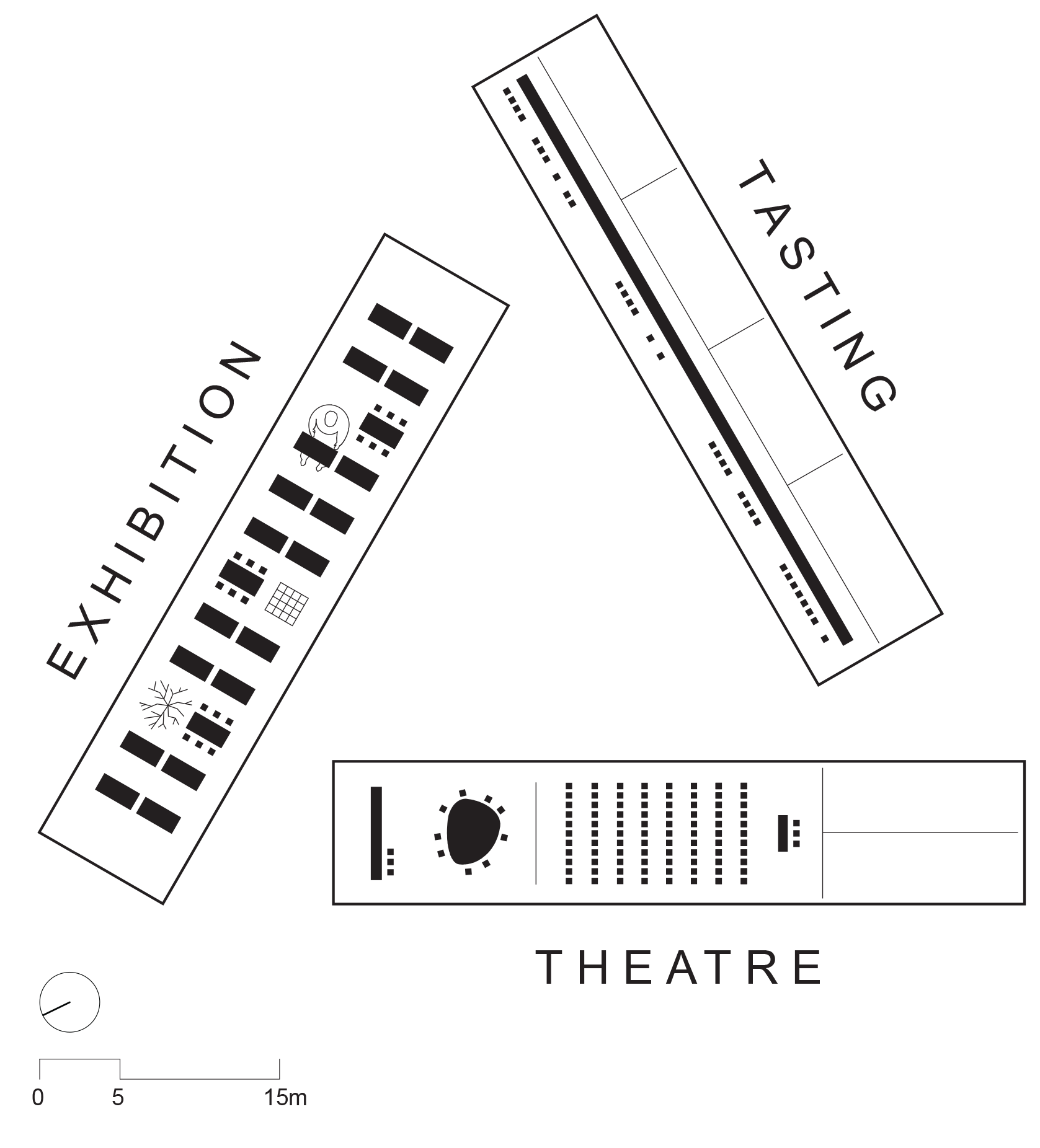

Much to your own surprise, you became involved with the Expo once again in 2014 when Carlo Petrini asked you to design the pavilion for the International Slow Food Movement. Why did you decide to work again within the framework of your own failed masterplan?That was only because of Carlo, who had been working with us on our ideas for the Expo from the very beginning. He was reluctant himself about joining a big show event like this, but had finally agreed to present Slow Food on a very prominent location within our grid: a triangular plot at the eastern end of the central boulevard, which we always imagined to become one of the main public forums.

We felt that it would be great to have Carlo and his ideas and convictions being represented, so we couldn’t resist. -

![]()

Herzog & de Meuron have designed three simple, open structures, like market stands, grouped around a triangular public space to present Carlo Petrini’s Slow Food Movement. (Image © Herzog & de Meuron)

-

»Most of all we have to overcome this ridiculous system of national pride represented by individual pavilion design«

A drone’s eye view of the Expo 2015 construction site, March 2015. (Video © Expo Milano 2015 World’s Fair)

-

Jacques Herzog was born in Basel in 1950. He studied architecture at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (ETH) from 1970 to 1975 with Aldo Rossi and Dolf Schnebli. He has been a Visiting Professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Design since 1994 and a Professor at the ETH Zurich since 1999.

Herzog established the architecture practice Herzog & de Meuron with Pierre de Meuron in 1978 in Basel. Today the company is run by five senior partners: the two founding members along with Christine Binswanger, Ascan Mergenthaler and Stefan Marbach.

An international team of 41 Associates and about 420 collaborators is working on projects across Europe, the Americas and Asia. The firm’s main office is in Basel with additional offices in Hamburg, London, Madrid, New York City and Hong Kong. Herzog & de Meuron have designed a wide range of projects from the small scale of a private home to the large scale of urban design. While many of their projects are highly recognised public facilities, such as their stadiums and museums, they have also completed several distinguished private projects including apartment buildings, offices, and factories. The practice has been awarded numerous prizes including The Pritzker Architecture Prize (USA) in 2001, the RIBA Royal Gold Medal (UK) and the Praemium Imperiale (Japan), both in 2007.

www.herzogdemeuron.com

I believe that our Slow Food Pavilion will demonstrate how we had imagined all the pavilions of this Expo to be. It is composed of three very simple shacks made of almost archaic wooden structures, like market stalls, which define a triangular courtyard, an open and communal space. After the Expo they will be easily dismantled and reassembled as garden sheds in school gardens around Italy, to be used by Carlo’s Slow Food Movement for their ongoing educative school programme.

Do you think that the upcoming Expo editions in Antalya, Astana and Dubai will pick up on the principles of your collective masterplan?I still believe that most of all we have to overcome this ridiculous system of national pride represented by individual pavilion design. Difference should be real, i.e. based on content, not on architectural design – basta! A World’s Fair must expose common topics and problems, presenting different ways of dealing with these problems in different regions of our world. That would be an amazing and exciting exhibition that I would be eager to visit on the very first day it opens. Yet of course this is much more difficult than to simply stick to the existing model, and that’s why unfortunately it is very unlikely that it’s going to happen anytime soon. I would rather expect the upcoming Expos to be more like the one in Shanghai again, trying to attract an ever-larger crowd of visitors.

If you say that so many people were convinced by the ideas inherent in your masterplan, what would it take to make things change in the future?As long as the Expos are more or less an economic success – at least to promoters of tourism – there will not be any fundamental change, simply because there is no real need to change anything. The Olympic Games are meanwhile viewed very sceptically in many democratic countries, which is at least partially due to the fact that they are a very profitable business for only a very few, and a financial disaster for the hosting city or country. As a consequence such events will increasingly take place in countries where democratic systems are not so well developed and such shows serve as propaganda for the political regime. I

-

In the Photo Booth with ...

Richard Van der LakenRichard Van der Laken, co-founder and General and Creative Director of the annual Amsterdam design conference “What Design Can Do” (WDCD) dropped round for a visit at the uncube office whilst he was in Berlin collecting supporters and speakers for the next edition of his design conference which takes place in May this year. The WDCD conference aims to explore what it says on the tin, seeking to be a call to action platform for designers. Sophie Lovell talked to Van der Laken about turning words into deeds.

Interview by Sophie Lovell

Photographs by Lena Giovanazzi

-

Over the past few years, attention within the disciplines of design has shifted away from “product” towards thinking, strategies and how design relates to people. What has prompted this shift in your view?

The crisis of 2008 made everybody think. Whether you were a salesman, butcher, banker or designer, everybody suddenly saw that this system, this society we are living in, could go down. I think that many people then began to ask themselves: “What can I do to make this world we live in more liveable, fair and clean?” When you ask yourself this question as a designer, you immediately have to step out of your comfort zone, and many designers now look further than their own discipline.

What led you, as a graphic designer, to co-initiate the WDCD conference five years ago?

The name of the event says it all. We wanted to share our vision that design can make a difference in society and show that it is not just about aesthetics.

-

»Yes, it is changing. A lot still has to happen though. The danger is that many organisations still see design as something they can use, but at the end of the process instead of the beginning. That is a pity.«

A lot of people outside the design world still believe that design is there just to make things prettier. Do you think that view is changing?

-

Seriously, can designers really make a difference? Are they not too much under the thumb of industry and marketing mechanisms?

Look at the Dutch designer Daan Roosegaarde, with his Smart Highway project, or innovator Bas van Abel who created a clean and fair cellphone called the Fairphone. They are good examples of how designers can act as initators. That is a big new role for designers: not waiting for an enlightened client to turn up, but doing it themselves.

How much of this kind of conference is about designers just presenting their ideas to other designers – preaching to the converted – and how much about actual implementation of those ideas? Do you not need to be reaching out more to people in industry, business, banking, government and administration – challenging how they think?

It is something we’re always struggling with. As a designer you should be able to answer the question: “What can design do?” (Although many designers still don’t know...) For us it is important to be a platform for that call to action for designers, saying: You have certain skills, please use them in the right way.

On the other hand we need industry and governmental organisations too. As a designer you are part of a big chain. -

The Dutch designer Richard van der Laken co-founded De Designpolitie with Pepijn Zurburg in 1995. The design practice consists today of a small international team of talented and ambitious designers and producers. They produce communication and identity design for clients in the non-profit and commercial sectors with an emphasis on cultural and social organisations.

They are also are the initiators, curators and organisers of What Design Can Do, an international event and movement about the impact of design on society. The next What Design Can Do conference is in Amsterdam on the 21 and 22 May 2015. uncube are media partners of the event.

Getting those parties inside and engaged is a difficult task. To stimulate this, we want to redeem the promise of WDCD by starting the What Design Can Do Challenge. It will include a call for proposals on the very pressing issue of refugees. Or to give it a slogan: What Design Can Do For The Refugee. We want international design teams to work on solutions – and make a difference.

One of the 2015 conference themes is politics. Where would you like to take WDCD in the future? What would you like to see it achieve beyond talking – or is talking enough?

Talking, and sharing thoughts, ideas, visions, and practices is important. We should not be blasé about this. But yes, we want to translate them into action. The WDCD Challenge will help deliver that. Hopefully it will be a success, then we will make it an annual event – with the goal, of course, of making a real impact. I

-

![]()

-

![]()

Issue No. 33:

April 30th 2015

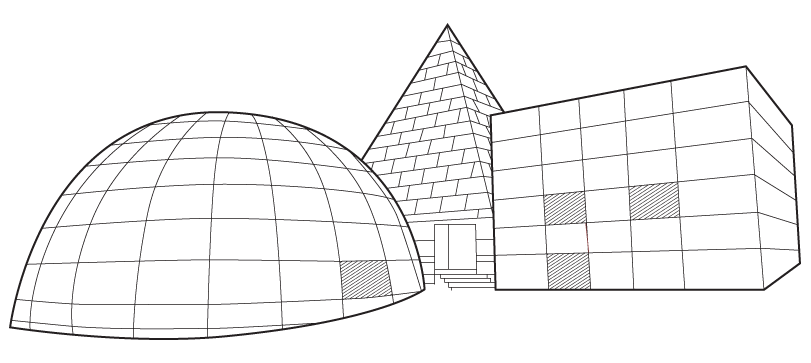

A model for the structure of the West German Pavilion designed for Montreal Expo 67 by Frei Otto.

(Collection of the German Architecture Museum (DAM), donated by Berthold Burkhart. Photo: Hagen Stier)

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Architecture starts when you carefully put two bricks together. There it begins.«

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents

Kiyonari Kikutake's Expo Tower. (Photo courtesy

Kiyonari Kikutake's Expo Tower. (Photo courtesy  The Takara Beautilion, designed by Kisho Kurokawa & Ekuan/GK. (Photo: Flickr/m-louis*)

The Takara Beautilion, designed by Kisho Kurokawa & Ekuan/GK. (Photo: Flickr/m-louis*) The Sumitomo Pavilion, designed by Sachio Otani. (Photo courtesy

The Sumitomo Pavilion, designed by Sachio Otani. (Photo courtesy